CHAPTER FIFTEEN

COACHING FOR GOVERNANCE

This chapter focuses on the specific context in which business coaching is delivered to those who are responsible for the governance of organizations. Motivated by the desire to improve business performance whilst recognizing business risk, “coaching for governance” focuses on an agenda for change through the deployment and leverage of board members’ strengths.

The Stormy Seas of Business Leadership

Picture the captain at the wheel of his fishing trawler, scanning the horizon, watching the sonar, walking the deck, and talking to his crew. Where should they drop their nets? The familiar fishing grounds are exhausted. New grounds are protected by conventions which favor fleets from specific countries. They must range farther across the seas, but where? The choice is critical given the price of fuel.

This is not the only critical decision facing the captain. Traditional trawling methods have been replaced by new ones. Net gauges have grown smaller, trapping everything in their path. Bottom clearing has devastated the seabed, leaving only those species which no one will eat or process. Flotillas of fishing craft have been replaced by factory ships served by a host of satellite trawlers, feeding their hungry maws. Locals are furious about the damage to their environment and the livelihoods of the leisure fishing industry. The trawler captain tries to balance the need to remain commercially viable with a need to recognize and accommodate the different perceptions of the community in which he lives. We can empathize with his position.

Now picture the captains of industry, facing many of the same challenges. They are often isolated high above the organization in their boardrooms, reliant on the information which filters through the corridors of power to inform their decision making.

The position of these modern business leaders is a diverse and challenging one. Urged to scan the horizon to spot trends that might have an impact on their strategic plans; tasked with establishing risk appetite and innovative direction; expected to instigate reporting processes which indicate where the rich fishing grounds exist and where the wrecks and reefs lie, which might hole their organization below the water line; encouraged to lead by example, be visible, walk the deck, and listen to the insights shared by internal and external stakeholders—particularly the disenfranchised, whose perceptions might challenge complacent thinking.

New business models have to align capability with continually evolving strategic direction. Just as the trawler captain has to understand cool chain technology and integrity in order to get his cargo to market fresh, so the twenty-first-century business leader must understand his reliance on a web of other organizations that choose to collaborate in supply chains in order to deliver value to end customers. Without delivering value to these customers, the business is unable to deliver value to any of its other stakeholders.

All this must be achieved in an increasingly regulated environment, with multiple definitions of what “good organizational behavior” looks like. The common message seems to be that a clear focus on the tone and leadership of the governance agenda is required. This is a sea change from the historic focus on board architecture and processes. Nowadays, business leaders are required to demonstrate that the strategic decisions they take balance commercial imperatives with corporate responsibility.

Leading an organization can be a lonely business. Each strategic decision has the potential to significantly impact the whole system which the leader is responsible for nurturing. Collective board responsibility for those decisions does not preclude individual liability. The roles of directors, whether executive or nonexecutive, are clearly defined at law and include statutory, fiduciary, and moral responsibility to deliver governance and stewardship, having taken account of an extensive range of stakeholder interests.

While an increasing number of business leaders are describing their organizations as having “learning cultures,” much of the actual learning takes place below board level. It is still relatively uncommon for boards to routinely assess the impacts of their strategic decisions or reflect on their collective and individual performance. To complicate matters, there is little security of tenure for the captains of industry, and their time in post can be limited by factors outside their own control.

Business coaching at board level enables good governance by recognizing the regulatory environment, the multiple roles which individuals are required to balance, and the complex dynamics involved at that level. The potential impact that changes to decision making and behavior can have to whole organizational systems is significant. The principles and approaches that define good governance vary globally from the rules to the principles based and the locus of power varies across unitary and two-tier boards, with all the attendant complexities this brings to strategic decision making. It is therefore naïve to assume that the approach which has been successfully adopted in one situation can be automatically translated to another.

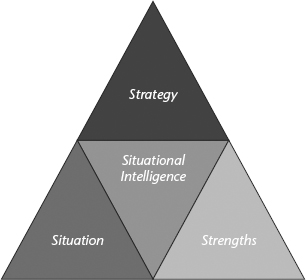

Rather than a remedial activity, coaching for governance focuses on enabling individuals and boards to build “situational intelligence,” developing their ability to read the “rich picture” of the situations they need to address. Being “savvy” involves recognizing the context in which the individual and the business operates. Successful business leaders couple “situational intelligence” with a real understanding of their individual strengths and those of their boardroom colleagues. This enables them to use judgment in the way they deploy their strengths.

Figure 15.1 shows the business coaching model used. Strategy is defined as the aspirational trajectory of the organization; situation consists of the policy to be enacted in order to realise strategy and the community of motivated stakeholders who must be considered; strengths are the natural talent which could be deployed by the individual; situational intelligence creates the “rich picture” and develops the wisdom to intervene in a manner most likely to achieve individual objectives.

FIGURE 15.1. THE SITUATIONAL INTELLIGENCE TETRAD™: THE LYONS-BATESON REFERENCE MODEL

Source: The Situational Intelligence Tetrad™: The Lyons-Bateson Reference Model ©2012 Laurence S. Lyons and Anna Bateson. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

The “rich picture” is formed by identifying all interested and impacted stakeholders, their aspirations and motivations, and the context in which these are likely to change. At a governance level, the organization, as a separate legal entity, is a critical stakeholder. Business leaders with governance responsibility are required to take into account the perceptions and expectations of this wide range of stakeholders when making and implementing strategic decisions. Stakeholder maps are complex, going far beyond those with a direct exchange relationship. Regulatory requirements include reporting on commercial, environmental, and societal impacts, and this drives a need to consider impacts on stakeholders from across this spectrum.

The emergence of new supply-and-demand dynamics, an increasingly competitive world, and complex value chains all require business leaders to engage across geographical, gender, and generational boundaries. Diversity of insights is directly correlated with high-performance boards. The logical case is clearly made. Diverse boards are more likely to recognize and understand the diverse needs of their customers and the communities they operate in. By structuring boards to be diverse and creating an environment in which alternative insights are expressed and listened to, these boards are more likely to make better strategic decisions. Better strategic decisions well executed are more likely to lead to improved business performance and deliver the value which the board is responsible for creating.

Given the compelling argument for creating more diverse boards, why is the reality often different? Diverse boards mean having to listen to people who don’t think like you, which may be exciting but is also challenging and often uncomfortable. Brave business leaders are inviting the new “Generation Y” into the boardroom. Raised in the digital era, Gen Y can help them to navigate and interrogate the rich and living library. The insights shared provide value to all parties. Boards are challenged to think in different ways, and their young talent is provided with real insights into the way in which strategic decision making and implementation happen. Whether these opportunities are called “internships,” ”reverse mentoring,” or ”shadow boards,” the benefits are significant.

Coaching for governance provides a challenging, yet supportive service for highly talented business leaders seeking to enhance board effectiveness. The service is discreet, addressing the potential reputational damage for business leaders of appearing “not to know” or “not to have thought about” the answers to the significant questions facing the business. The service is timely and flexible, recognizing the reality of most business leader’s schedules. The expectation that they will be available at all times, coupled with the challenges of global and instant connectivity, have increased the “noise” which each individual has to filter in order to generate the key insights necessary to guide their strategic decision making.

Providing both a physical and virtual service, the business coach enables the business leader to “filter noise” and focus on the specific challenge they wish to address, the critical questions which require answering, and the alternative strategic paths available. Just as a nonexecutive director provides independent and constructive challenge to their executive board colleagues, so the business coach provides a robust thinking framework in a nondirective manner. The relationship provides time for reflection and review of alternatives and avoids the adoption of an unconsidered drive to action.

By clearly establishing and continuously reviewing the business leader’s coaching objective, a living agenda is created to deliver value to both the individual and the organization they lead. When asked to describe the value they have derived from coaching for governance, business leaders frequently identify direct links between specific decisions and actions they have taken and business performance improvements.

The events that trigger requests for coaching for governance are often associated with organizational step changes. These include changes to the composition of the board, the transition of key individuals into new posts, alterations in ownership structures, and changes in strategic direction for the organizations being governed. Most growth strategies generate these events, whether through organic or acquisitive activities. They can also generate a desire to invest in the development of strategic capability in the boardroom.

Annual board reviews can prompt the request for governance coaching for whole boards, specific committees, or individual members. Organizations often ask for a service which integrates a combination of coaching audiences over a period of time, generally between three and six months in duration. Although there are occasions where a longer relationship is desirable and effective, the frequency of structured sessions is likely to reduce to periodic reflective sessions to review strategic performance and aspirations.

The professional business coach will avoid creating mutually dependent, long-term relationships and ensure that the issue of transition is transparently discussed. Like board succession planning, this approach ensures that the client receives the service from those best placed to provide the constructive challenge required as time progresses and avoids the cozy dangers of “groupthink.”

The development agendas arising from annual board reviews generally cover the structure, composition, processes, and dynamics of those boards. Changes in structure and composition often lead to a need to reestablish common purpose across the board and explore the roles and effectiveness of all members, particularly the chairman. Coaching for governance also enables business leaders to reflect on the effectiveness of various board processes, including policy formulation, strategic decision making, and the establishment and leadership of risk appetite.

Whereas other forms of business coaching are often procured through HR departments, the need and providers of coaching for governance are often identified by board members themselves, with support from the company secretariat. The latter are uniquely placed to provide insights to the chairman on the specific governance coaching objectives which form part of the board’s development agenda. These insights inform the choice of suitable providers of this tailored service.

In order to be successful, coaching for governance relies on creating business relationships that are based on mutual trust and respect but not mutual dependence. The service is not one to be successfully brokered by experts in transactions, seeking to “sell on,” or those providers with the one model to fit all circumstances. Rigid and blind process providers are to be avoided.

Effective providers have experience of complex, real-world business and organizational issues, and interpersonal dynamics. They combine an appropriate mix of coaching, facilitation, and consultancy capability and are likely to engage in a joint due diligence process to establish that they can create real value for their clients before agreeing on the most effective approach. It is easy to underestimate the time and effort required to create a common understanding between client and provider, and also to build the trust required to engage in an effective coaching for governance relationship.

Coaching for Governance in Practice—Case Study

The Company

Ten years ago, two entrepreneurs set out on an exciting voyage. They each brought different strengths to their partnership and a clear determination to create a technical advisory business around the rail industry. Focused on providing high-level strategic advice to key decision makers across the supply chain, they forecast and achieved double-digit growth to £1m turnover within the first five years.

The Characters

John is decisive and brings drive, determination, and a commercial focus. Andy is reflective and brings a marketing focus and a concern for stakeholder interests. Together they complement each other in their ability to assess the upside and downside risks of the strategic options they develop. They visibly share a clear set of values, which guide their decision making and behavior: being open to new ideas and sharing them; being flexible and adapting to the situations they confront; being diligent and applying honest endeavor; and, finally, being principled and guided by the human ideals of fairness, honesty, loyalty, mutual respect, and a concern for people.

The Journey

Their company, CDL, prospered and achieved double-digit growth of 11 percent per annum over the first seven years. After eight years, the business consolidated its operations from York, in the northeast of England, to the London-based office. The workforce expanded to eighty. As the company grew, John and Andy recognized the need to invite others to join them in the leadership of their business and to have a share in the ownership. They invested in the professionalization of their board and also appointed a nonexecutive chairman.

Following a business growth strategy which involved extending their global operations, in 2009 they set up a wholly owned subsidiary in Sydney, Australia. Working hard to align their business model to their strategy, CDL focused on developing a reputation for high-quality, strategic advice and distinctive competitive advantage based on service excellence and relationships. As the business grew and the global recession impacted and changed their markets, John and Andy recognized that the business and governance models needed to evolve to make them fit for the future.

Both John and Andy were aware of the challenges and tensions they faced as founders, in determining their future involvement in the business they had cocreated. John identified that a business coaching process would enable him to think through the business situation; the opportunities, challenges, and options available; and also his own aspirations and motivations. He invited Andy to participate and, after some discussion, a common agenda and objective were agreed. They shared this intention with all board members, highlighting their need to realign their own thinking as founders, major shareholders, and directors of the business. All their business coaching discussions recognized the governance challenges of balancing these different and conflicting roles. The discussions also highlighted the requirements to engage with a wide range of stakeholders during the process.

The Process

Over a period of seven months, Andy and John met together regularly for formal business coaching sessions with the author. These meetings were held away from the pressures of the office and the schedule was largely protected from operational change and national and international travel requirements. Their commitment to the value of the process was evident, and they were active in sustaining momentum. A living business coaching record also sustained momentum and created focus by capturing their decisions and their commitments throughout the process. Between the formal sessions, the author provided virtual support and John and Andy met together informally and as part of their strategic and operational business roles. A midterm evaluation of the process established the value being realized and made some modifications to the documentation that had been developed up to that point in the process.

The business coaching sessions provided a safe environment in which to have difficult conversations. The governance context provided a constructive way of challenging perceptions and ensuring that strategic options were explored in a robust and rigorous fashion.

The Results

Among the strategic options being explored by the board of CDL were a number of approaches by businesses interested in acquiring them. One of these approaches was from global consultancy, GHD (Gutteridge, Haskins, and Davey), who intend growing a UK/European transportation business, to build on their global network of regional offices. That deal was completed on July 1, 2011.

The business coaching undertaken by John and Andy contributed to the careful evaluation of all strategic options against the board’s governance agenda and their own aspirations as founders and major shareholders. The deal recognizes the right cultural fit between the two businesses and GHD’s values of teamwork, respect, and integrity. Future roles have been devised for the founders and other directors of CDL to ensure that value will be preserved and enhanced in the business during the transitional period.

The Value

John and Andy are clear about the value that they and the business have derived from engaging together in the business coaching process, commenting that, “For the investment, we got a big return. The return you get is extremely powerful.”

By asking critical questions at key points in the process, the author enabled John and Andy to understand and evidence the real value of the business as well as more clearly articulating their own aspirations in preserving and realizing that value. “It gave us time to discuss and think about important issues and align ourselves. Once we were aligned, we could talk together, with one voice.”

The business coaching process was based on mutual trust and respect. “It took us on an emotional and mental journey. We had to be brave and very open. It gave us perspective and reminded us of our different strengths and roles. You need to be open minded when you do this. There is no clear route. Timing is the only issue, I wish we had started this much sooner.”

Anna Bateson (www.cttg.org) works globally with boards and business leaders, addressing the challenges of leading strategic change and delivering good governance. Described by the business press as “a skilled alchemist,” she shares pragmatic insights gained over four decades in leadership and consultancy roles with international businesses including Price Waterhouse and British Airways.

As a business writer and columnist for Chartered Secretary and through her strategic alliance with The Institute of Directors, Anna is closely involved in the design, development, and delivery of a range of initiatives to address governance challenges and professionalize boards.

Through her business consultancy, Cutting Through The Grey, and jointly with global thought leader Dr. Laurence Lyons, Anna researches, coaches, and consults on the development and deployment of “Situational Intelligence.” Anna has an MBA from Brunel University and was a founder corporate member of The Henley Future Work Forum.

Further Reading

Bain, Neville, and Barker, Roger. 2010. The Effective Board. London: Kogan Page.

Bateson, Anna. 2011. “A Clearer Focus.” Chartered Secretary. www.charteredsecretary.net and www.cttg.org.

Bateson, Anna. 2008. Another Board Bites the Dust. Institute of Directors (IOD) www.cttg.org.

Bateson, Anna. 2005. Leading the Advanced Organisation. Institute of Directors (IOD) www.cttg.org.

Burkan, Wayne. 1996. Wide Angle Vision. New York: Wiley.

ecoDa and Institute of Directors. 2010.Corporate Governance Guidance and Principles for Unlisted Companies in the UK. www.iod.com.

Financial Reporting Council. 2011.Guidance on Board Effectiveness. www.frc.org.uk.

Financial Reporting Council. 2010.The UK Corporate Governance Code. www.frc.org.uk.

Garratt, Bob. 2011. The Fish Rots from the Head (3rd ed.). London: Profile Books.

Institute of Directors. 2009. The Handbook of International Corporate Governance (2nd ed.). London: Kogan Page.

Lewis, Richard. 2008. When Cultures Collide. London: Nicholas Brealey International.

Lyons, Laurence S., and Bateson, Anna. 2006. Leadership—A Principled Approach. www.cttg.org; www.lslyons.com.

Lyons, Laurence S., and Bateson, Anna. 2009. “How to Crack the Toughest Leadership Challenge of All.” A Lyons-Bateson Summit Paper. www.cttg.org; www.lslyons.com.

Lyons, Laurence S. 2012. “The Tetrad (Lyons-Bateson Situational Intelligence Reference Model),” in The Coaching for Leadership Case Study Workbook: Featuring Dr. Fink’s Leadership Casebook. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

PSCI. 2007. Pharmaceutical Industry Principles for Responsible Supply Chain Management and Implementation Guidelines. www.pharmaceuticalsupplychain.org.

Sull, Donald N. 2009. The Upside of Turbulence: Seizing Opportunity in an Uncertain World. New York: Harper Collins.