CHAPTER SIXTEEN

LEADERSHIP INSIGHT1

Going Beyond the Dehydrated Language of Management

The soul . . . never thinks without a picture.

—Aristotle, 384–322 bce

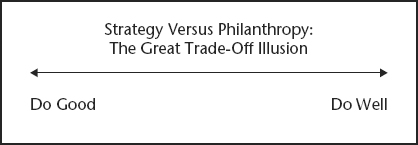

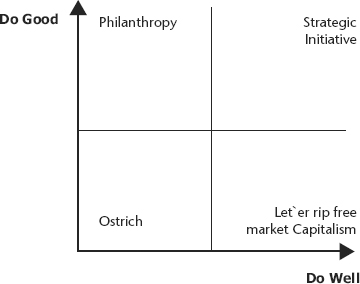

Eight-hundred million people go to bed hungry every night, including more than 300 million children. Every 3.6 seconds, a person dies of starvation. Most companies consider such poverty-related tragedies to be society’s problem, not the primary concern of business. They not only fail to see the more than three billion people who live on less than $2 a day as an opportunity, but they remain completely blind to the possibility that they might constitute a lucrative market (Prahalad, 2006). Belief in the great trade-off illusion (see Figures 16.1 and 16.2) has insidiously blinded most managers into assuming that the choice to do good precludes the ability of corporations, along with the executives who lead them, to do well. Most managers falsely assume that the more they focus on enhancing societal well-being, the worse their companies will perform financially. At the close of the twentieth century, business widely embraced the illusion that generosity and compassion were bad for business.

FIGURE 16.1. STRATEGY VERSUS PHILANTHROPY: THE GREAT TRADE-OFF ILLUSION

FIGURE 16.2. DOING WELL BY DOING GOOD: 21ST CENTURY STRATEGIC SUCCESS

But by the beginning of the twenty-first century, global business strategist Gary Hamel articulated what a small but growing number of executives were beginning not only to recognize, but to act on:

What we need is not an economy of hands or heads, but an economy of hearts. Every employee should feel that he or she is contributing to something that will actually make a genuine and positive difference in the lives of customers and colleagues. For too many employees, the return on emotional equity is close to zero. They have nothing to commit to other than the success of their own career. Why is it that the very essence of our humanity, our desire to reach beyond ourselves, to touch others, to do something that matters, to leave the world just a little bit better, is often denied at work? . . . To succeed in the [twenty-first century] . . ., a company must give its members a reason to bring all of their humanity to work. (Hamel, 2000, 249)

Reflecting the same human desire to leave the world a better place, the Rev. Rick Warren’s 2002 book, The Purpose-Driven Life, became one of the world’s all-time best sellers. Nowhere in The Purpose-Driven Life does it say that managers and executives are exempt from the human craving for purpose and meaning. Hamel (2000, 24), a business strategist, not a theologian, reminds business people that God commanded the nomadic Israelites to rest one day out of seven—but that God did not “. . . decree that the other six had to be empty of meaning.” Hamel (2000, 248) coaches executives to embrace “a cause, not a business . . . Without a transcendent purpose, individuals will lack the courage” they need to innovate beyond the ordinary. “Courage . . . comes not from some banal assurance that ‘change is good’ but from devotion to a wholly worthwhile cause” (Hamel, 2000, 249).

When you cease to dream, you cease to live

—Malcolm Forbes, Forbes magazine (as cited in Bryan et al., 1998, p.25)

Twenty-first-century society yearns for a leadership of possibility, a leadership based more on hope, aspiration, wisdom, and innovation than on the replication of historical patterns of constrained pragmatism.2 Luckily, such a leadership is now possible, although unfortunately still rare. For the first time in history, leaders can work backward from their aspirations and imagination rather than forward from the past. The gap between what leaders can imagine and what they can accomplish has never been smaller (Hamel, 2000, p. 10).

Designing options worthy of implementation calls for levels of inspiration, perception, and innovation that, until recently, have been more the province of artists and artistic processes than the domain of most managers. To meet the challenges of the twenty-first century, we increasingly need artistic imagination to co-create the planet’s best approaches and most influential solutions:

There is a good practical reason for encouraging our artistic powers within organizations that up to now might have been unwelcoming or afraid of those qualities. The artist must paint or sculpt or write, not only for the present generation but for those who have yet to be born. A good artist, it is often said, is fifty to a hundred years ahead of . . . [his or her] time . . . The artist . . . must . . . depict this new world before all the evidence is in. They must rely on . . . their imagination to intuit and describe what is yet a germinating seed in the present time, something that will only flower after they have written the line or painted the canvas. [Leaders] . . . must learn the same artistic discipline, they must learn to respond or conceive of something that will move in the same direction in which the world is moving, without waiting for all the evidence to appear on their desks. To wait for all the evidence is to finally recognize it through a competitor’s product. (Whyte, 1994, 241–242)

Leading in the twenty-first century calls not just for creativity, but for approaches based more on anticipation, imagination, and personal sense-making than on conventional entrepreneurial experimentation, no matter how creatively conceived (Botkin et al., 1979). The potential for irreversible, catastrophic outcomes caused by companies’ and governments’ experiments gone awry—from global economic collapse and mass famine to nuclear holocaust and species extinction—renders such traditional approaches as no longer acceptable. To embrace the type of leadership the twenty-first century most needs, managers must return to their most profound personal perspective, imagination, and wisdom.

Leadership Insight: Seeking Wisdom Through Reflection

[W]hen we are in the buzzing-worker-bee mode . . . [w]e do not even have time to find out if our momentum is taking us over the nearest cliff. If we are serious about [who we are as leaders] . . ., all of us must confront the question of quiet and contemplation in the workplace. (Whyte, 1994, 98)

More than 2,500 years ago, Confucius admonished leaders to seek perspective and wisdom through reflection, rather than simply attempting to learn through experience and imitation (Sharma, 2008). Confirming Confucius’s understanding, Harvard professor Howard Gardner’s (1995) contemporary research identified daily reflection as one of only three core competencies (along with leveraging and framing) that distinguish leaders who make an extraordinary difference in the world from their more ordinary counterparts. Management guru Peter Drucker (1999) similarly advocated daily reflection, as have many of the most prominent leadership experts (see, for example, Loehr and Schwartz’s Harvard Business Review article [2001] and Palmer’s 2000 article “Leading from Within”). Even with such admonitions to regularly engage in personal reflection and sensemaking, management and leadership, both as taught and as practiced, have focused almost exclusively on action rather than reflection. Most managers guard little or no time for reflective silence. They all too frequently recognize themselves in the words of poet and global management consultant David Whyte that opened this section.

Aspiring to Leadership That Matters

To be truly radical is to make hope possible

—Lovins, 2007

What do managers need to do to strengthen their capacity to lead wisely and creatively in the twenty-first century? How can executives best envision and implement initiatives that matter? Building on Confucius’s wisdom and Gardner’s research, along with the yearnings and experience of hundreds of managers from around the world, it is clear that today’s leaders need to:

- Reflect—to return to the quiet and contemplation it takes to be wise;

- Gain perspective—to acquire the courage needed to see reality as it actually is, rather than continuing to rely on illusions perpetuated by colleagues, the media, and the broader culture;

- Aspire to exceptionally exciting possibilities—to envision extraordinary possibilities by drawing on the depths of their own and others’ hopes, aspirations, and creativity; and

- Inspire others—to inspire people to move beyond current reality back to possibility.

Based on these four fundamental leadership capacities and drawing from a range of artistic traditions, we created a journal that can be of significant practical value and serve as a prototype for other journals. The Leadership Insight journal (Adler, 2010b) supports managers’ and their companies’ capacity to craft and implement strategies that produce outstanding financial results by making a positive difference in the world (see Figure 16.2). Combining paintings, insights from world leaders, reflective questions, and, most important, blank pages, the journal is designed to draw managers away from their often frenzied lives and to return them to a deeper dialectic with their influence, and potential influence, on the world. By reintroducing a daily practice of reflection, the journal offers leaders the quiet and contemplation it takes to be wise.

Reflection: Coming Back to Your Unique Perspective

To be human is to find ourselves behind our names.

—David Krieger (as cited in Franck et al., 1998, 272)3

All true leadership starts with coming home to oneself. The blank pages are the journal’s most direct invitation to spend time quietly recollecting (literally recollecting) one’s personal perspective. They challenge us to take ourselves as seriously as we take the people whom we most admire. Do not simply listen, read, and repeat what others say. Grant your own perceptions, ideas, images, feelings, and dreams the same respect that you give to the world’s most respected leaders. True leaders, whether in the arts, business, government, science, or the military, view the world through their own eyes, their own values, and their own dreams.

The journal acts as an antidote to society’s pervasive collusion. It acts as a barrier against the persistent attempts by the media, politicians, and every organization’s culture to pressure us into seeing the world as others see it. The blank pages symbolically admonish each of us not to collude with illusion, but rather to make sense of the world for ourselves. Prior to the last election in which the predominantly French-speaking province of Quebec was deciding if it would separate from the rest of Canada, management guru Henry Mintzberg spoke out, urging his fellow citizens: “Turn off your radio and TV, and open your window. Look outside and see Quebec with your own eyes. Do our French- and English-speaking children play together? Do we invite each other into our homes? Do we work together? Yes! It is an illusion that the Anglophone and Francophone people from Quebec do not get along with each other; an illusion that serves the needs of politicians who want to break Canada apart, but it is not reality.” Don’t collude with illusion!

Some of the imagery in the Leadership Insight journal is more obvious, while other imagery is more subtle. Whereas the blank pages directly invite managers to come back to themselves, the symbolism of the cover design is less evident. The design was created from a pattern of names (they are literally the names of my friends, family, and colleagues). In the same way that each name is personal, each journal is personal. Like the blank pages, the individual names invite you to record your own point of view, not that of others. Regaining the courage to express, when appropriate, one’s own perspective is essential for meaningful leadership. To support leaders in reclaiming their unique perspective, one of the questions we ask each person to ponder is: “If you spoke up right now, in your own voice, what would be most important for you to say? To whom? In what tone of voice?” (Whyte, 1994).

While inviting each person to acknowledge his or her own unique voice, the journal never presents any one person as the leader. The names on the cover are from every region of the world. As you pick up the journal, you are being invited to join a global community of leaders, not to aspire to become the leader. As a leader, your voice is unique, but always embedded in a global network of influence. While your perspective is rooted in its distinct cultural, national, ethnic, geographic, and professional experience, and is therefore unique, specific, and local, the collection of perspectives from around the world is global. Leadership in the twenty-first century is created by a global network of leaders, never by a single person, no matter how competent or powerful (Adler, 2011a & b).

We stand on the shoulders of giants

—Sir Isaac Newton, 16764

No person ever contributes significantly to the world without profoundly knowing his or her roots (see, for example, U.S. President Barack Obama’s 1995 memoir, Dreams from My Father). As a leader, it is difficult to offer a vision or a new idea without having developed the type of courage that comes from appreciating the depth of one’s personal and cultural history. When Newton declares that “We stand on the shoulders of giants,” he is acknowledging that past generations of leaders support each of us in learning to see the truth, hear the truth, and speak the truth. There is no such thing as leadership with shallow roots.

In addition to the names on the cover, scattered throughout the journal are handwritten insights from women and men, representing an array of countries, professions, and eras, who have given all of us our collective roots as leaders. Examples include Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffet (as cited by Bryan et al., 1998, ix):

I am not a businessman, I am an artist.

Former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, who states:

Let us choose to unite the power of markets with the authority of universal ideals. Let us choose to reconcile the creative forces of private enterprise with the needs of the disadvantaged and the requirements of future generations.5

Founder and CEO Emeritus of VISA Dee Hock (1998), who states:

. . . it is no failure if you fall short of realizing all that you might dream, the failure is to fall short of dreaming all that you might realize.

Also, the reflection of Ryuzaburo Kabu (as cited in Sbarcea, 2007, 3), the Honorary Chairman of Canon, Inc:

To put it simply, global companies have no future if the earth has no future

Each leader’s reflection challenges us to think more broadly about the circumstances we face. That the leaders’ handwritten reflections are in your journal, next to your own handwritten reflections, represents the invitation from these extraordinary individuals to join the community of leaders who are shaping our economy and society. As former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright (1997) eloquently stated in her Harvard commencement address: “We have a responsibility in our time, as others have had in theirs, not to be prisoners of history, but to shape history.” Albright did not exempt any of us from the invitation or responsibility to shape history. And in the quietness of our own personal reflection, we know that there is no wiser, smarter, or more committed group somewhere else in the world who will take care of everything for us.

Painting Leadership: Going Beyond the Dehydrated Language of Management

Let the beauty we love be what we do.

—Rumi, thirteenth-century Persian poet6

In addition to blank pages, leaders’ insights, and the names on the cover, the Leadership Insight journal presents a collection of paintings, each of which is an invitation to think visually and thus to reflect on the world from a new lens. Experiment with your own visual thinking. Think for a moment about the most compelling visual images from the last hundred years—the images you clearly remember of the most significant moments in the world’s history. You might recall an image of the moon landing, or the fall of the Berlin Wall, or the mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima, or the birth of your first child. What can you learn about your overall perspective from the particular images you chose?

Now think about the last ten years of your organization’s history. What are the images of distinctive moments that stand out for you in that history? What role did leadership play in helping to create each defining moment?

Now think back over the last year. Which two or three images capture your personal best moments of leadership? What can you learn about your strengths from these distinctive moments of contribution (Roberts et al., 2005)? How could there be more moments similar to these personal high points in the coming year? Whether or not we are aware of the process, we all think visually. The images we remember give meaning to our understanding of the world and our role within the world. Similar to our own memories of important events, some of the paintings in the journal present whole images while others reveal only fragmented details—the global and the local, the universal and the particular.

Artists do not always aspire to craft works of beauty. The paintings included in the journal, however, were purposely chosen to evoke beauty. Even during one of the most challenging periods of world history, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt repeatedly reminded people, “The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.” The paintings offer a way to return to the beauty we each aspire to in our leadership, in our lives, and in our dreams.

In attempting to transform organizations and society, two seemingly opposite philosophies guide leaders. In the more common problem-focused approach, companies and organizations attempt to improve by finding what is not working and then on solving the problems they have found. Instead of concentrating on weaknesses and problems, the alternative approach focuses on magnifying and leveraging strengths. Beauty is not “a problem to be solved.” By reflecting beauty, the paintings in the journal evoke people’s (and organizations’) strengths and dreams. The paintings thus support leaders in striving to be their best—to use their strengths and leverage their aspirations to guide their organization and their contributions to the broader society. Beauty is neither about fixing problems nor about being satisfied with “good enough”; rather, it is about reaching for the very best that we and society can be (Adler, 2008). Bringing the two approaches together, futurist Buckminster Fuller reflected that:

When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty. I think of only how to solve the problem. But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.7

The order of the paintings in the journal was carefully selected to support leadership reflection. As you open the journal, the first painting you encounter is a joyful sunflower painted in bright reds, yellows, and oranges. Its vibrant energy evokes the busy activity of most managers’ everyday life. Echoing the transition from high-energy action to reflective calm, each successive painting becomes quieter and softer. When you reach the final painting, it presents an ephemeral moon in a peaceful blue-green landscape—a landscape that is only reachable once you leave the frantic busyness of action and return to the peaceful calm of reflection.

Each painting invites the viewer to go beyond the dehydrated language of management and return to the richer images of leadership. The paintings included in the journal were created using water-based media (watercolors and ink). Being water-based, they symbolically bring water—and thus life—back into those aspects of one’s life and leadership that have become dry, mechanical, and thus lifeless. As you reflect, ask yourself what brings life (water) back into the dehydrated aspects of your own leadership?

Still Life: An Invitation to Reflect

Some doors open only from the inside.

—Ancient Sufi saying8

There is a tradition in the visual arts of painting a “still life,” usually thought of as a centuries-old canvas filled with nicely arranged fruit or flowers. To really see the paintings, we need to still our life. We can’t skim to read a painting; we have to stop to actually look at it. It is new. What do we see? How does it make us feel? What images does it conjure up in us? The journal invites us to enter into this artistic tradition and to “still” our life.

As we slow down, the paintings encourage us to notice what surrounds us—the context within which we live and lead. They encourage us to stop multitasking long enough to simply concentrate on the one thing that matters most to us right now. Without periodically stopping, it is impossible to gain the perspective needed for leadership.

An experiment conducted at Yale University demonstrated the power of viewing paintings to support professional excellence. When medical students were shown paintings in an art history course that Yale had experimentally added to their curriculum, the young doctors’ diagnostic skills improved markedly (Dolev et al., 2001). Viewing the paintings taught the physicians to see their patients (and the world) more accurately. It taught them to appreciate multiple perspectives while not missing the small details. It taught them to become more comfortable with “not knowing” (what managers often refer to as tolerating ambiguity) long enough to accurately diagnose their patients’ maladies rather than prematurely settling on a diagnosis based only on the initial, superficial pattern of symptoms. Much to the surprise of the medical school’s leadership, viewing paintings significantly helps physicians save lives.

Experiment for a few minutes with slowing down your own fast-paced life. Choose one of the journal paintings or a painting from your own collection and view it, uninterrupted, for three to five minutes. As you stop multi-tasking and concentrate on the single painting, notice the change in the quality of your observation, insight, and experience. Then ask yourself how often you give yourself this quality of uninterrupted time and concentration? What in your life deserves this quality of attention? What in your leadership deserves this quality of attention? What in the world deserves this quality of your attention? What would your leadership be like if, as a regular practice, you gave this quality of attention to the challenges, goals, people, and dreams that matter most to you and to the people you work with (see Adler, 2004)?

The senior executive team of a major nutrition company gathered recently in Montreal to identify global strategies that could help them achieve even better performance than their current industry-leading standard. After exploring a range of strategic options, this group of extremely competent and effective executives chose to take time to reflect on what was most important to them. Individually, they asked themselves what inspired them most about working for the company. What led them, at least on some mornings, to jump out of bed, eager for another day at work?

As they shared their personal reflections with their international colleagues, a striking pattern emerged. The majority revealed that they no longer eagerly looked forward to another day at work. They confided that increasing profits, while challenging, was not inspiring. Faced with their current dwindling enthusiasm, they began to recall why they had originally chosen to work for this particular company, rather than for a firm in another industry. They remembered their desire to work for a company that helped people live a healthier life.

As the executives brought their personal observations back into their more focused discussion of corporate strategy, they almost immediately conceived a new initiative that galvanized the group: a profit-making venture to provide basic nutrition for the world’s poorest people, starting with rural Africans—a population they had never considered before. As soon as the idea emerged, the executives quickly crafted innovative marketing, production, and distribution processes for Africa to make the company’s products both accessible and profitable to this currently underserved market. What was most striking about the plan (beyond it being an excellent corporate initiative) was that it never would have occurred to the executives if they had not been willing to stop and to reflect back—on their core values and aspirations—and then to reflect forward about their collective dreams for the company.

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso—the founder of cubism, a multiple-perspective approach to painting that predates by a century the needs of today’s leaders to see the world from multiple points of view—saw painting as just another way of keeping a journal. I first took a group of global executives to an exhibition of cubist paintings as the final session of a three-day meeting in Oslo designed to integrate the firm’s latest series of intercontinental mergers and acquisitions into the company’s overall strategy. Standing in the museum’s cubist gallery, the CEO was astonished to discover that the cubists had captured exactly the perspective that he felt the company most needed to move from operating as a European company to succeeding as a global firm. Artists prior to the cubists had used single-point perspective—the artists painted images as if there was just one viewer standing at a specific location looking at the painted scene. The cubist revolution overthrew single-point perspective and presented the same image from multiple points of view within a single painting. Once he had seen the cubist paintings the European CEO realized that his company would be able to benefit from its recent Asian and North and South American acquisitions only if it was able to simultaneously view global markets, as well as global competitors, from multiple national and cultural perspectives. Similar to the most basic cubist paintings, competitive positioning requires creating synergy out of disparate views of reality. As the global company continued to grow, it not only became skillful at drawing on the often divergent views of its world wide network of executives and operating entities, it repeatedly positioned itself for success within its industry (see Adler, 2002).

The paintings in the journal were selected to support global managers in reflecting on their own best selves and best leadership, and to encourage them to welcome the ambiguity and uncertainty that such reflection provokes. As world-renowned Australian art critic Robert Hughes underscored, the greater the leader and “the greater the artist, the greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is [only] granted to the less talented as a consolation prize.” As the Norwegian-based multinational learned, there is never just one perspective or one point of view. Global leadership demands the ability to recognize and build on differences—to create cultural synergy, not worldwide global integration (see Adler, 2002).

Reality in Translation: Asking the Right Questions

Now that we can do anything, what do we want to do?

—Bruce Mau, designer (Mau and The Institute without Boundaries, 2004, 15)

A good question always transforms how we see the world. It guides us in what we notice and what we overlook—in which patterns we emphasize and which we ignore. Throughout the Leadership Insight journal, questions such as the following challenge our perspective as leaders:

- What do you most want to do this year to make the world a better place?

- Why do people want to be led by you?

- With whom do you have conversations that matter?

- What do you find most difficult to face in your relationship with your work? Your career? Your life?

Because each question in the journal is printed on semi-transparent paper, they symbolically lead us to view the world through the question and thus transform our view of reality.

The semi-transparent paper for the pages with questions and the opaque paper for the blank pages bring together an Asian and a Western tradition. The semi-transparent, rice-paper-like Asian pages and ecologically certified opaque Western pages complement each other, while remaining distinct. They create a synergy—a bringing together of multiple distinct perspectives, ideas, cultures, or elements to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The journal does not combine the various types of paper into one homogeneous composite paper. Unity in diversity, not homogenization, is the physical essence of the journal. Likewise, and more important, it is the essence of well-functioning twenty-first-century companies and the core of flourishing global societies.

Ultimately, the Leadership Insight journal is a call to wise action, not simply a tool for contemplation. “The fierce urgency of now,”9 as U.S. President Barack Obama labeled it, calls on all twenty-first-century leaders to act. Leadership always happens in the moment. It does not wait until we are older, or better prepared, or have a larger savings account, or a bigger title. The call is now. The invitation to respond is now. The plea is to do so wisely, and with generosity and compassion.

Nancy J. Adler is the S. Bronfman Chair in Management at McGill University, Canada. She conducts research and consults worldwide on global leadership. She has authored 125 articles, produced two films, and published ten books and edited volumes. She is a Fellow of the Academies of Management and International Business, and the Royal Society of Canada. She is also a visual artist. Nancy J. Adler can be contacted at: nancy.adler@mcgill.ca.

References

Adler, N. J. 2002. “Global Companies, Global Society: There Is a Better Way,” Journal of Management Inquiry 11, no. 3: 255–60.

Adler, Nancy J. 2004. “Reflective Silence: Developing the Capacity for Meaningful Global Leadership” in Nakiye Avdan Boyacigiller Richard Alan Goodman, & Margaret E. Phillips (eds.), Crossing Cultures: Insights from Master Teacher. London, England: Routledge: pp. 201–218.

Adler, N. J. 2006. “The Arts and Leadership: Now That We Can Do Anything, What Will We Do?.” Academy of Management Learning and Education 5, no. 4: 466–99.

Adler, Nancy J. 2008. “The Art of Global Leadership: Designing Options Worthy of Choosing” in Daved Berry and Hans Hansen (eds.), Handbook of the New & Emerging in Organization Studies. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, pp. 95–96.

Adler, Nancy J. 2010a. “Going Beyond the Dehydrated Language of Management: Leadership Insight,” Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 31 (no. 4): pp. 90–99.

Adler, Nancy J. 2010b. Leadership Insight. Milton Park, U.K.: Routledge.

Adler, Nancy J. 2011a. “Leading Beautifully: The Creative Economy and Beyond”, Journal of Management Inquiry, vol. 20 (no. 3) September, pp. 208–221.

Adler, Nancy J. 2011b. “New Times Need New Leadership” in Danica Purg (ed.), Creating the Future: Book of the Times 2011. Bled, Slovenia: IEDC-Bled School of Management: pp. 25–34.

Albright, M. K. 1997. Harvard commencement address. New York Times, June 6, p. A8.

Botkin, J. W., Elmandjra, M., and Malitza, M. 1979. No Limits to Learning: Bridging the Human Gap—A Report to the Club of Rome. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Bryan, M., Cameron, J., and Allen, C. 1998. The Artist’s Way at Work: Riding the Dragon. New York: Harper.

Dolev, J. C., Friedlaender, F., Krohner, L., and Braverman, I. M. 2001. “Use of Fine Art to Enhance Visual Diagnostic Skills.” Journal of the American Medical Association 286, no. 9: 1020.

Drucker, P. 1999. “Managing Oneself.” Harvard Business Review, March-April: 65–74.

Franck, F., Rose, J., and Connolly, R. (Eds.). 2000. What Does It Mean to Be Human? New York: St Martin’s Press.

Gardner, H. 1995. Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership. New York: Basic Books.

Hamel, G. 2000. Leading the Revolution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hock, D. 1998. “An Epidemic of Institutional Failure: Organizational Development and the New Millennium,” Keynote Address at the 1998 Organizational Development Network Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA, available from www.hackvan.com/pub/stig/etext/deehock–epidemic-of-institutionalfailure.html.

Loehr, J., and Schwartz, T. 2001. “The Making of a Corporate Athlete.” Harvard Business Review, January: 120–128.

Lovins, A. 2007. Keynote address at the Global Forum on “Business as an Agent of World Benefit: Management Knowledge Leading Positive Change” Cleveland, Ohio, October 27.

Mau, B. and The Institute Without Boundaries. 2004. Massive Change. London: Phaidon Press.

Obama, B. 1995. Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Palmer, P. 2000. “Leading from Within,” in Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 73–94 .

Prahalad, C. K. 2006. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits—Enabling Dignity and Choice Through Markets. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing.

Roberts, L. M., Spreitzer, G., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Heaphy, E., and Barker, B. 2005. “How to Play to Your Strengths.” Harvard Business Review, January: 75–80.

Rumi, J. A. 1995. The Essential Rumi. Banks, C. with Mayne, J. (trans.), Ch. 4.

Sbarcea, K. 2007. “Corporate Sustainability and the Role of Knowledge Management: Preliminary Exploration.” February, available at: http://thinkingshift.files.wordpress.com/2007/02/km-sustainability.doc.

Sharma, G. 2008. “Choosing Wisdom Through Reflection: How Businesses Can Achieve a Healthy Bottom-Line by Ensuring a Healthy Planet.” BAWB Newsletter (on-line), May 16, available at: http://worldbenefit.case.edu/newsletter/?idNewsletter=153&idHeading=54&idNews=630.

Warren, R. 2002. The Purpose-Driven Life. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Whyte, D. 1994. The Heart Aroused. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Further Reading

To view Adler’s Leadership Insight journal go to http://www.mcgill.ca/desautels/beyond-business/art-leadership/journal. Copies of the Leadership Insight journal are available from the publisher at http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415877626/ or from online bookstores. To see more of Adler’s art and her work on art and leadership, go to McGill University’s website at: http://www.mcgill.ca/desautels/beyond-business/art-leadership/

1 An earlier version of this article was published in Adler, Nancy J. (2010a) “Going Beyond the Dehydrated Language of Management: Leadership Insight,” Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 31 (no. 4): pp. 90–99.

Notes

1. Article originally published in Journal of Business Strategy 31, no. 4 (2010): 90–99.

2. The opening section based on Adler’s (2006) “The Arts and Leadership: Now That We Can Do Anything, What Will We Do?” Academy of Management Learning and Education Journal 5, no. 4 (2006): 486–499.

3. Note that all page numbers refer to the original first edition published by Circumstantial Productions.

4. Paraphrase of Sir Isaac Newton’s “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” in Newton’s February 15, 1676 letter to Robert Hook.

5. Address by Kofi Annan at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in 1999.

6. Rumi from his poem “Spring Giddiness” as translated by C. Barks and J. Moyne (Rumi, 1995).

7. Fuller as cited at Wisdom Quotes: www.wisdomquotes.com/000976.html.

8. As cited at The School for Mindful Living website: www.schoolofmindfulliving.org/quote/quote.html.

9. Reverend Martin Luther King’s famous plea of “the fierce urgency of now” was often quoted by President-Elect Barack Obama when describing the importance of Americans realizing that we are at a defining moment in our nation’s history.