CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

COACHING TOOLS FOR THE LEADERSHIP JOURNEY

The road to effective leadership can be a rocky one and the way ahead is not always clear, particularly for new managers. In his book The First 90 Days1 Michael Watkins reveals that it normally takes more than six months for leaders in new positions to start contributing to the bottom line. Coaching can shorten that time period, as well as establish a firm foundation for exceptional leadership over the course of a lifetime.

In this article we’ll discuss two coaching tools that are particularly effective in accelerating the new leader’s journey to effectiveness: Relationship Mapping and Leadership Point of View.

Just as a Sherpa guide knows the way up the mountain, so the executive coach knows the steps along the leadership journey. In fact, the stages people go through on their leadership journey are fairly predictable.

When people join companies—especially young people trained in specific skills—they usually start as individual contributors. They have key responsibility areas directly linked to their particular expertise. They may be part of a team, but as individual contributors they are judged by the quality of their individual work.

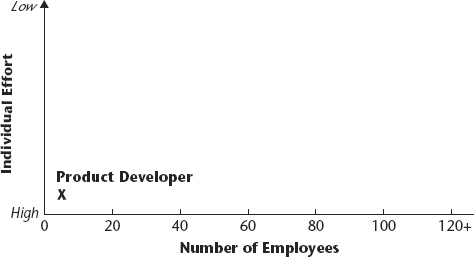

Tom’s leadership journey is a good example. Tom came into the company as a product developer. His job was to find out which new products had been approved for the pipeline and to shepherd them through the development cycle. He worked with the marketing and sales departments, but he was an individual contributor with high individual effort and no direct reports. (See Figure 28.1.)

FIGURE 28.1. LEADERSHIP EFFECTS OF COACHING

As individual contributors increase their technical competence, they frequently are promoted into management roles. Often, they have no management experience and limited interpersonal skills, especially if their fields are highly technical.

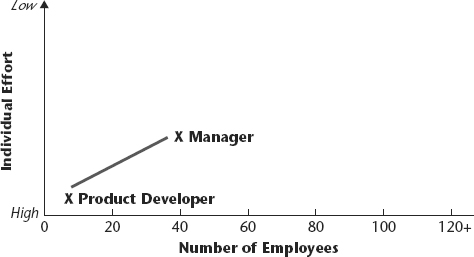

When Tom was promoted into management, his effort as an individual contributor decreased as his number of direct reports increased. Tom no longer had the freedom to get the job done on his own. He had to get it done through others. (See Figure 28.2.)

FIGURE 28.2. LEADERSHIP EFFECTS OF COACHING

One of the hardest things for technically proficient, smart people to realize is that as they assume more and more leadership responsibility, they must continue to increase their dependence on the goodwill and help of people at all levels of the organization. Each of these “others” is an individual who needs to be seen, heard, and understood by their leaders in order to maximize the potential they offer. At this point, Tom’s organization provided him with a coach who introduced him to a tool called Relationship Mapping.2

It was critical for Tom to map his key relationships to understand how each could impact his performance. Relationship Mapping is an ideal tool to use when strategizing a new project, beginning a new role, or running into unexpected obstacles in a specific area. The secret to using this tool effectively is to know and be able to articulate:

- Key goals and milestones

- The plan to achieve goals

- Who will be affected by the achievement of goals

- How each of these people can either help or hinder success

- What can be done to leverage helpers

- Tactics for possible damage control

The Relationship Mapping Process

Taking the time to really think through relationships requires a great deal of discipline and adherence to a specific process. To begin, Tom’s coach had him take a large piece of flip chart paper and clearly identify what, exactly, needed to be accomplished. Because there were several goals, Tom’s coach had him create a relationship map for each. Next, Tom drew a box for each person who might be affected by the efforts involved in achieving the goal. Like many people working on Relationship Maps, Tom worried about going overboard, but his coach assured him it was best to think of as many people as possible and then scale back, if needed. Tom included all relevant senior leaders, colleagues in the industry, peers in other departments, direct reports, functional reports, and dotted-line team leads.

Once all possible stakeholders were on the map, Tom answered the following questions for each person:

- What are their main goals and objectives?

- How will it serve them for me to succeed—or fail?

- What is needed from them?

- How can they help—or hurt—the project?

- What is the person’s thinking style? What will be needed to most effectively communicate and influence him or her? For example, does she like a lot of detail or would she prefer the executive summary?

- What attitudes does the person have about me? Is there respect, credibility, trust?

- How do I feel about the person? Is there any judgment or bad history to complicate things?

Once this process was completed for each person, Tom thought about what he had learned. He immediately saw that some individuals were less important to the success of the project or goal than he had previously thought, whereas others were more important and might have been overlooked.

Creating Action Plans with Relationship Maps

At this point in the Relationship Mapping process, Tom needed to create a mini action plan for deepening his relationship with each individual on the map. Action plans can include spending time together, going to the person to ask for advice, or picking up the phone simply to get an opinion about something. Tom planned several lunches and coffees with the individuals he needed to get to know better. It was a real stretch for him to overcome his introversion, but he made himself do it and found that it wasn’t as hard as he’d initially expected. He began to include several new people on relevant e-mails, and made it a point to drop by certain cubicles that were not on his regular path.

With one particular person, Tom realized that mistakes had been made and that past misunderstandings were getting in the way of clear communication. The air needed to be cleared. Tom forced himself to pick up the phone and ask for a meeting to discuss what had happened in the past, forge an improved relationship, and agree on a new way to move forward. This proved to be a critical and extremely positive decision.

Action plans for each individual should include methodically paying attention to how people use language. In Tom’s case, he needed to understand what was important to others, what they focused on, how they thought, and how they approached things.

How people communicate their understanding offers useful clues to how they process information. If they say “I see,” in all likelihood they are literally swayed by visual images and graphics. “I don’t feel comfortable” is often used by kinesthetic learners who respond better to a document in their hand than to an electronic copy. Those who remark “I hear what you’re saying” are likely to be auditory learners who respond best to verbal communication.

As Tom learned to listen carefully—to assess whether someone wanted to be told or shown, whether they wanted the detailed plan or the cut-to-the-chase outcome—his effectiveness soared. Tom began to develop a reputation for being an excellent communicator who got the job done.

This is a critical point in coaching. Leaders on an upward path must decide if they want to continue their upward movement, or not. In Tom’s case, he had to think about whether he wanted to retain some pieces of his role as an individual contributor or transition to a predominantly leadership position, depending on and developing others.

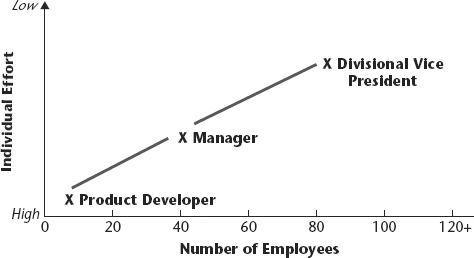

Tom found that he loved leading others and excelled at it. As a result, he was given increasingly more responsibility. Over time, top management was so impressed with his ability to build relationships while maintaining his technical expertise that he was promoted to divisional vice president with new responsibilities. (See Figure 28.3.) Tom no longer did much individual technical work because he set the strategic direction for an entire division. He thrived with the change.

FIGURE 28.3. LEADERSHIP EFFECTS OF COACHING

Leaders at this level in the organization are responsible for getting almost all their work done through others. Tom now had eighty people reporting either to him directly or through his direct reports, and his division was responsible for $35 million in revenue. It was at this point that Tom realized he had too many employees under him for all of them to know him well. He needed to find a way to be a truly inspirational leader without having personal contact with everyone. Again, Tom’s coach was there with a tool that helped him make the crucial shift from manager of processes and people to leader: The Leadership Point of View.

Leadership Point of View3 (LPoV) is a credo that encompasses not just a leader’s vision for the work, but also shares personal background that has influenced the leader’s beliefs and expectations about leadership. The LPoV expresses what is most important to the leader and offers examples that help people understand and remember what has been shared. Whereas the Relationship Mapping process focuses on the leader’s development, the LPoV focuses on others, telling them what they need to know about their leader to work effectively with him or her.

Tom’s coach explained to him that his LPoV would express what he expected of others and what others could expect from him. By sharing his LPoV, Tom would make explicit what had up to now been implicit. He would set an example for his people and encourage them to think about their own beliefs about leading and motivating people. Finally, Tom’s LPoV would serve as his road map for actions he would choose when stressed or in a crisis.

Tom was delighted by this assignment, although it was harder than he initially expected. He was not nearly as clear about his LPoV as he thought he would be, and he had to work on it in stages.

Ken and Margie Blanchard developed the Leadership Point of View process after reading Noel Tichy’s book, The Leadership Engine.4 Tichy’s extensive research has shown that the most effective leaders have a clear, teachable LPoV, and they are willing to share it with others.

The Leadership Point of View Process

To develop his LPoV, Tom needed to answer some questions. The answers to these questions generated more questions, required a great deal of thought, and in the end yielded rich and varied answers. Tom began his LPoV exploration by asking: who are the leaders who have inspired me and had an impact on my beliefs about leading and motivating people? He thought about all kinds of people from the past and the present, real and fictional. One of Tom’s favorite leaders was Abraham Lincoln, whose humility he loved. Another leader, known only to Tom, was his middle school soccer coach, Mike. What a motivator he had been! Tom created a list of these leaders.

Once his list was finished, Tom took each of the leaders from the list and asked:

- What qualities does this person have that I find so impressive?

- What have they done that I find so inspiring?

- What lessons am I learning from them about leadership?

One of Tom’s personal examples was Atticus Finch, the protagonist of the novel To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee.5 Atticus Finch was a caring and committed parent, yet he chose to stand up for justice in his small town at great risk to himself and his children. By thinking about why he found Atticus Finch so inspiring, Tom realized that he was committed to doing the right thing even when it wasn’t popular or convenient.

The list of qualities and actions revealed what Tom thought was important for a leader. These were his leadership values. These values, it turned out, were different from any official corporate values his company had. Because these values were personal and drove his behavior, he saw that it was critical to know what they were and share them with his people.

Using his list of qualities and actions, Tom was able to reflect on the next question:

- Is there something about me that would be helpful for others to know that would make them more effective in working with me?

Through his LPoV work it became clear to Tom that although he believed a leader should be kind and appropriate at all times, this would be a lifelong challenge for him personally. He knew that despite his best efforts, his dry and mischievous sense of humor would cause him to fail sometimes to live up to his own standards. Because he might occasionally slip up and crack inappropriate jokes, Tom decided that part of his LPoV would be to prepare and warn people about this.

This led Tom to the next question:

- What can people expect from me?

His coach convinced Tom that letting people know what they could expect from him would demonstrate Tom’s belief that good leadership is a partnership. It would also give his people a picture of how things would look under his leadership.

In reflecting on what he expected and what people could expect from him, Tom knew that he wanted people to win. Therefore, they could expect him to roll up his proverbial sleeves and help, whether they needed a sounding board or someone to brainstorm solving a problem.

As Tom thought about this aspect of his LPoV, it felt risky to share with his people exactly what they could and shouldn’t expect from him. He realized that it gave implicit permission for them to call him on his behavior when what was promised went undelivered. In talking to his coach, he realized that although sharing was risky, it was the only way to foster the trusting environment he wanted for his people.

The next question forced even more clarity for Tom:

- What do I expect from my people?

Tom realized in talking with his coach that expectations can go from the explicit—like accomplishing agreed-upon goals—to the implicit—such as, “I expect my people to do what they say they are going to do.” Tom intuitively understood that people like to know what is expected of them. They want a clear picture of what the leader thinks a good job looks like, because it provides them with a sense of safety. That certainly was true for him.

In talking with him about what people could expect from Tom and what Tom could expect from people, Tom’s coach emphasized how important it was that he give an example for each major expectation, so that they could see themselves within each expectation.

After many hours and much thought, Tom created a draft LPoV in writing. His first attempt was ten pages long, which he finally whittled down to a three-page document. Once that was complete, he had to answer the last key question about his LPoV:

- How will I share this information with others?

He knew that reading the document to people would not be very motivating. Instead, he committed his LPoV to memory, so that when he shared it with his people he could look them in the eye and make a sincere presentation. Tom’s coach encouraged him to make a date with himself to revisit his LPoV annually to see if it needed to be updated.

Tom also came to rely on his LPoV as a working document for himself. As he recently told his coach, “I refer to it when I have a hard day and forget who I am. I’ve been glad to have it in this downturn. It’s like an emergency kit I keep on hand.”

Putting the LPoV to Work

For coaches who want to do Leadership Point of View work with their clients, it is important to remember that creating a LPoV is a process that takes time. The work can be done in a number of ways. Each client is going to have a different thinking and learning style. Visual leaders are going to want to see the questions in writing. Auditory ones will want to be talked through it. Very few will be able to answer the questions off the top of their heads. Many will want time to reflect and make notes.

One client who worked insane hours and went home to three kids designated a couple of her driving commutes to thinking through the questions, and then she left voice mails for her assistant to transcribe and e-mail back to her. A highly extroverted, “think out loud” entrepreneur hosted a dinner party with his most interesting friends during which he conducted a lively guided discussion around the questions. He gleaned amazing thinking, and as an added bonus he received some keen insights into what leadership attributes he already had. Another leader got the best results from long, solitary walks, after which she wrote up some notes. There is no right way to generate answers, but the coach can help each individual find the best way for him or her. Once the process begins, it will be a work in progress over the course of the leadership tenure. For some that will mean the rest of their lives.

Finding Your Leadership Point of View

- Who are the leaders who are inspiring to you?

- What qualities do they have? What did they do that you found inspiring?

- Can you do these things? Do you possess these qualities? If not, can you develop them? If not, what will you do about it?

- What do you expect of yourself and others?

- What can others expect of you?

- How will you share this information with others?

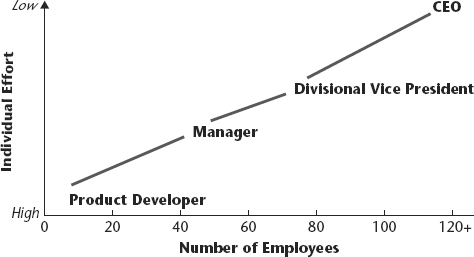

Tom’s record as a divisional vice president was exemplary. So when the CEO retired, no one was surprised that Tom was promoted to the top spot. When leaders are promoted to CEO, they are fully responsible for creating, establishing, and living the organization’s vision, values, and mission. They must focus on strategy and building a leadership team. They must network with other CEOs and learn quickly what is working and what is not. They must make hard decisions about how to solve problems, often with no road map.

The technical skills Tom brought to his organization have long since been set aside. They once served him well, but no longer. As CEO, Tom now produces all results through the work of others and is held responsible by all stakeholders for the company’s success or failure. (See Figure 28.4.)

FIGURE 28.4. LEADERSHIP EFFECTS OF COACHING

Getting things done with and through others is an executive trait. To master this skill, it helps to have a detailed map of every single person who is going to make a significant contribution, so Tom uses Relationship Mapping to this day.

At their best, executives lead others to excellence so that the entire organization succeeds. Tom regularly shares his LPoV, as does each member of his executive team, increasing the level of trust and the quality of conversations in the organization. Tom now spends every hour of every day helping others achieve their goals, connecting them with the best resources, and removing the obstacles in their paths. All the while, he inspires them with the organization’s vision and values.

Ken Blanchard is one of the most influential leadership gurus in the world, respected for his groundbreaking work in leadership and management. He is the author of dozens of books, including the blockbuster international bestseller The One Minute Manager® and the giant business best-sellers Raving Fans and Gung Ho! His books have combined sales of nearly 20 million copies in more than 27 languages. In 2005, Ken was inducted into Amazon’s Hall of Fame as one of the top 25 bestselling authors of all time. He is the cofounder and chief spiritual officer of The Ken Blanchard Companies, an international management training and consulting firm headquartered in San Diego, California. The College of Business at Grand Canyon University bears his name.

Madeleine Homan Blanchard is the team lead for Blanchard Certified, an online leadership development system, and she is a cofounder of Coaching Services for The Ken Blanchard Companies. A coach since 1989, Ms. Homan Blanchard was instrumental in developing the core curriculum for Coach University, where she was a founding advisory board member and senior trainer. She was a founding board member of the International Coach Federation, where she served on the board for six years. Previously, Ms. Blanchard founded Straightline Coaching, a coaching service firm devoted to life and work satisfaction for creative geniuses. She spent two years as the program director for a coaching program that rolled out to 2,100 individuals globally for the IT division of an international investment bank. She is the coauthor of three books: Coaching in Organizations; Leverage Your Best, Ditch the Rest: The Coaching Secrets Executives Depend On, and Leading at a Higher Level. She is also coauthor of The Ken Blanchard Companies’ coaching skills program Coaching Essentials for Leaders.

Linda Miller is the Global Liaison for Coaching at The Ken Blanchard Companies. In this role Linda has coached and trained leaders from Europe, Asia, and Central and South America. In addition, she is known for her ability to communicate what coaching is and how it can be applied in organizations. Since 1996, Linda has been an active member of the International Coach Federation and is a founding recipient of the Master Certified Coach designation. She and Madeleine Homan Blanchard are coauthors of Coaching in Organizations: Best Practices from The Ken Blanchard Companies®. During the 2008 and 2010 election cycles Linda moderated political debates at the legislative level throughout Arizona. In 2009, she was awarded an honorary doctorate recognizing her contributions to the field of coaching.

Notes

1. Michael Watkins, The First 90 Days (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2003).

2. See Scott Blanchard and Madeleine Homan, Leverage Your Best, Ditch the Rest: The Coaching Secrets Top Executives Depend On (New York: William Morrow, 2004).

3. See Ken Blanchard and the Founding Associates and Consulting Partners of The Ken Blanchard Companies, Leading at a Higher Level: Blanchard on Leadership and Creating High Performing Organizations (Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press, 2009 and 2010).

4. Noel Tichy, The Leadership Engine: How Winning Companies Build Leaders at Every Level (New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

5. Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1960).