CHAPTER THIRTY

THREE TYPES OF HI-PO AND THE REALISE2 4M MODEL

Coaching at the Intersection of Strengths, Strategy, and Situation

The need for learning and change in a dynamically complex global environment has never been greater. The increasing pace of globalization. The emergence of the BRIC economies—those of Brazil, Russia, India, and China—as major global players. The talent tidal wave that has been unleashed through the economic emergence of China and India. The Great Recession of 2008–2009. How the Hi-Pos (those with high potential) cope with—or even capitalize upon—these circumstances will determine if, how, and how far they succeed as they become the next generation moving into the corporate C-suite. Their Hi-Po type will also be instrumental in the pathways that might be open to them and the development they will need to succeed. Our experiences suggest there are three types of Hi-Pos: the Hard-Wired Hi-Po, the Hard-Working Hi-Po, and the Humble Hi-Po. Each has its own different development needs and performance trajectories. Determining the Hi-Po type with whom we are working helps us to better understand what they need in order to succeed, and what we can best do to help them.

The Hard-Wired Hi-Po has grown up with the belief that they are the best of the best. Prep school, private school, Ivy League or Oxbridge university. top of the class, house captain, member of the varsity elite. Then graduate entry and leadership fast-track with the heavy label of “High-Potential.” OK—we stereotype to draw the caricature—but our point is a simple one. With this gilded existence helping them to glide into the elite, these Hi-Pos can wear their labels as a badge of honor, but also as a heavy burden of expectation to bear—and one which is exacerbated by the curse of the fixed mindset.1

The fixed mindset can be an unwitting consequence of high intelligence, precocious success, and early achievement. It is the view that “I’m one of the brightest people in this company, so everything should be easy for me.” Unfortunately, for people with a fixed mindset, the implication is that everything should be easy and that they don’t need to put in the effort—that they should never fail, that mistakes are something confined to lesser mortals. As is apparent, the fixed mindset is anathema to the deep requirements for learning and change that pervade modern corporate life. The fixed mindset leads to the belief that “I will be found out because I can’t actually do what is expected of me—and I’m too afraid to try in case I might fail.”

The consequences for the Hard-Wired Hi-Po can be debilitating. On the one hand, they expect (and believe that others expect of them) that success is a given, to be assumed, rather than earned. Their superior talent, ability, intellect, or charisma is all they need to float to the pinnacle of whatever they desire. Hard work, effort, failure, learning—“These don’t come into it. They’re for others, not for me.” The fixed mindset is the belief that everything I have is what I deserve and what I was born with. As a result, anything that challenges this belief, that causes the Hard-Wired Hi-Po to think that they might not just be so special after all, presents a major threat. It is easier to walk away than to fail, easier not to try than to admit defeat—and so self-sabotage can be a key indicator of when the fixed mindset is at work in the Hard-Wired Hi-Po.

In contrast, the Hard-Working Hi-Po is characterized by the abundance of learning, change, and growth that they have enjoyed (and endured) along the way. This may often have been as a result of challenge, disappointment, and trauma—but all will have been used as the crucible of experience to forge their growth mindset and resilience for success. Such Hard-Working Hi-Pos will undoubtedly be intelligent—but they will never have taken that intelligence for granted, and their intelligence will likely be more street smarts than just book learning.

The work ethic, commitment, and engagement of the Hard-Working Hi-Po will be predictive of the sheer effort they have expended in their desire to learn, to adapt, to change, and to progress through the vicissitudes of life. As the Hi-Po talent pool has widened immeasurably with the growth of the BRIC economies and the earlier emergence of the Asian tigers (the highly developed economies of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan), so has the breadth and diversity of the Hi-Po population—and the experiences they have had, the mindsets they bring with them, and the assumptions that they consider normal.

With this fundamentally different attitude and mindset, the Hard-Working Hi-Pos see every challenge as an opportunity, welcome the unknown as potential to be embraced, and use adversity as stepping stones for their further change, learning, and growth. In contrast to their Hard-Wired Hi-Po colleagues, the Hard-Working Hi-Po is characterized instead by their growth mindset—the belief that their destiny was not fixed at birth, but instead that their trajectory can be shaped and influenced by the effort they put in and the learning they pick up along the way.

The third of our class is the Humble Hi-Po—the genuine contender who can’t really see that they are that special or why they should be where they are. Although in some ways this might be seen as a variant of the imposter syndrome that has been recognized for the last thirty years,2 there are subtle differences. The Humble Hi-Po may be confident in himself to an extent, but equally cannot see how he is special compared to others—a phenomenon that we have often observed in high-achieving women and especially high-achieving Asian women (a possible gender and gender X culture interaction difference). They attribute the credit for their successes and achievements to circumstance, good fortune, the efforts of others, or the serendipity of finding themselves in the right place at the right time. All of these may indeed have had a part to play—but the Humble Hi-Po risks losing sight of his or her own contribution and significance if he or she plays this hand of humility too far. As ever, the balance to be struck is a sensitive one that calls to mind Aristotle’s “golden mean”—the right thing, to the right amount, in the right way, at the right time.

Equally, the Humble Hi-Pos may be seen as strong leadership candidates, naturally possessing the attributes of the Level 5 leadership virtue of humility, espoused by Jim Collins, amongst others.3 We have been struck by just how often we have seen humility feature as a team strength in the Realise2 Team Profile4 of high-performing leadership teams—but interestingly, a lot less frequently in leadership teams that are not high performing.

In sum, the humility of the Humble Hi-Pos can become debilitating when it starts to undermine the contributions they genuinely make and the impact they exclusively have. In this way, humility overplayed becomes a weakness, as it trips up the Humble Hi-Pos from doing what they need to do and being recognized for it. In the alpha-male environment of some organizations, humility is tantamount to career suicide. Humble Hi-Pos have to recognize this and dial back on their humility if they are to succeed. Crucially, this doesn’t mean that they have to become something they are not—just that they need to develop the situation-sensing agility of knowing when it is right to speak up for themselves, and when it is right to let others take the credit—which they will always be willing to take!

Helping the Hi-Pos: The Realise2 Strengths Model

On one level, the Hard-Wired Hi-Po, the Hard-Working Hi-Po, and the Humble Hi-Po have very different development needs to address. On another level, they share a common humanness. This can be captured by the strengths approach that helps ground them in a surer sense of who they are at their best, what they do well, and what they love to do.

Strengths are the things that we do well and love to do. In traditional thinking on strengths, they are simply understood in terms of performance (“What I am good at”). But this isn’t enough, since a strength is also characterized by the experience of energy when we’re using it (“What I enjoy and what gives me energy”). Further, for a strength to deliver outcomes, it has to be used, and use in itself is by definition variable, situational, and dynamic.

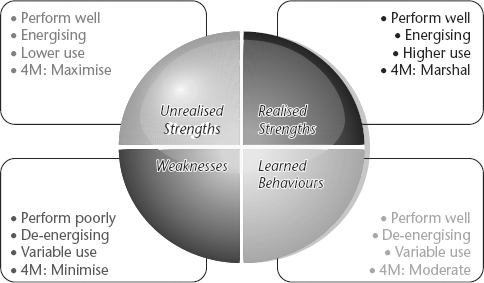

Taking these three elements together, we define a strength as being comprised of performance, energy, and use. These three dimensions combine in a number of different ways along a high-low axis, and together represent the four possible combinations of energy, performance, and use, which define the four quadrants of the Realise2 4M Model5 (see Figure 30.1):

FIGURE 30.1. THE REALISE2 4M MODEL

Source: Copyright 2011 CAPP. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission of CAPP.

1. A realized strength is characterized by high energy, high performance, and high use.

2. An unrealized strength is characterized by high energy and high performance, but lower use.

3. A learned behavior is characterized by lower energy but high performance, while use may be variable.

4. A weakness is characterized by lower energy and lower performance, while again use may be variable.

These four characteristics—realized strengths, unrealized strengths, learned behaviors, and weaknesses—together make up the four quadrants of the Realise2 4M Model. The four “Ms” refer to the advice that follows from the model, following clockwise from the top right:

1. Marshal realized strengths—use them appropriately for your situation and context

2. Moderate learned behaviors—use them in moderation and only when you need to

3. Minimize weaknesses—use them as little as possible and only where necessary

4. Maximize unrealized strengths—find opportunities to use them more.

Coaching Hi-Pos with the Realise2 4M Model

The first fundamental of strengths coaching with the Hi-Po population is that it can help them to achieve a grounded understanding of their strengths, but also their learned behaviors and their weaknesses. This grounding of strengths helps to underpin the personality integration that is integral to their realizing their potential and moving on and up to deliver greater success. The impact of this is subtly different for each of the three Hi-Po types:

- For the Hard-Wired Hi-Po, understanding the situational context around strengths, and appreciating the dynamic interaction between strengths and situations, can help them to recognize that their internal world is not as fixed as they might first have thought. This reframing toward adaptability and agility can transform their mindset and outlook, enabling them to transform their performance as a result.

- For the Hard-Working Hi-Po, the distinction between strengths and learned behaviors is often experienced as the light bulb moment. This group is most likely to have understood their strengths as “what I am good at” and so to have confused their learned behaviors in this way, accepting that hard work and effort are the entry ticket to success. When they start to recognize that high performance can be something that you deliver by doing things you enjoy—as well as sometimes knuckling down and just doing the things that need to be done—their perspective and performance can quickly step up a level.

- For the Humble Hi-Po, the recognition, acceptance, and reinforcement of the strengths they have can help to unlock their sense of their own value, and release them from the prison of feeling like an impostor to their own success. As they develop a language for, and integration of their strengths, they grow into their own skins, increasing their authenticity, confidence and performance as a result.

With the identification and recognition of strengths firmly under way, our coaching then typically moves on to helping the Hi-Pos work around the four quadrants of the Realise2 4M Model:

1. Marshal your realized strengths and align them to your goals and objectives, because you are more likely to achieve them by using your strengths.

2. Watch out that you moderate your learned behaviors, using them as much as appropriate but not too much. Learned behaviors are there to be called on when needed—but not overused.

3. Learn how to minimize your weaknesses, so that they don’t have a negative impact on your performance. You might do this by finding ways to use your strengths to compensate, working with other people, in partnership or in teams, or even learning how to develop the weakness so that it’s “good enough.”

4. Find opportunities to maximize your unrealized strengths and use them more in achieving what you want. Your unrealized strengths are a goldmine of untapped potential.

5. Having worked through the cycle, put it into practice. After a month, three months, or six months, come back and review. Strengths are dynamic, situations are ever changing. See what has changed for you and what you need to do about it, so that you can continually perform at your best through realizing your strengths, moderating your learned behaviors, and minimizing your weaknesses.

Crucially for Hi-Po development, the Realise2 4M Model is a dynamic model, and Realise2 is a dynamic assessment tool. As situations change, so might the strengths we use in those situations change as well. It’s called adaptation, something that we humans have been doing for hundreds of thousands of years through our evolution to become the people and the species that we are today. Unfortunately, on the fast track to success, Hi-Pos don’t always recognize this need for adaptation, and instead think that they need to do what they have always done, and then do more of it as they strive to succeed ever more. Situational judgment here comes into its own. The need for the practical wisdom which Aristotle defined as phronesis—the ability to judge, decide, and practice doing the right thing in the right way to get the right result—has the potential to become the sine qua non of future C-suite success.

As we work with Hi-Pos on coaching them for their strengths, it is therefore critical to recognize that their strengths are just one part of the three axes of the individual-organizational-environmental triangle with which they need to contend if they are to step up to the mark and deliver the leadership performance their organizations require. The other two axes relate to strategy (organizational direction) and situation (environmental context), which together form the 3S-P Model that we have developed in conjunction with colleagues Laurence Lyons and Anna Bateson.6

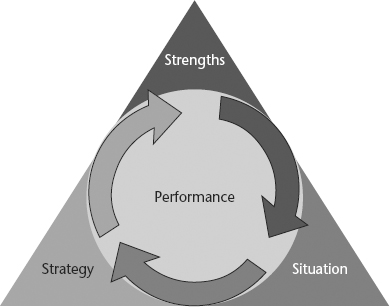

The 3S-P Model: Performance at the Intersection of Strengths, Strategy, and Situation

The central premise of the 3S-P model is very simple. Strengths used in the absence of context (situation) and direction (strategy) are just hobbies. Strategy in the absence of environmental awareness (situation) and an understanding of the capabilities to deliver it (strengths) is just a wish upon a star. Situation knowledge provides context, but in the absence of a direction of travel (strategy) and a means to get there (strengths), it is just wallpaper—providing a nice backdrop to what is going on around us. However, at the intersection of these three factors when they come together, we find the necessary foundation and sufficient capability for the delivery of Performance—thereby defining the 3S-P Model (see Figure 30.2).

FIGURE 30.2. THE 3S-P MODEL

Source: Copyright 2011 CAPP. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission of CAPP.

Our coaching of Hi-Pos is therefore structured to take account of these three domains. Typical coaching questions include:

1. Strengths

- What strengths can you use to help you achieve your objectives?

- How are your strengths perceived within the organization?

- Are there strengths that you need to dial up or dial down?

2. Strategy

- What are you trying to achieve and why?

- What are the major impacts that will help or hinder you getting there?

- Why is doing this the right thing for the organization to do? How can you ensure it will help the organization achieve its mission and purpose?

3. Situation

- What is your current context and how does this impact you?

- What is changing in the world that will influence the decisions you’re making?

- Is there a match between your strengths and strategy and your situation? If not, what can you do about it?

As the coaching session works through the deeper understanding and dynamic integration of strengths, strategy, and situation, so a more complex but complete and integrated perspective emerges of the Hi-Po and what he or she needs to do to deliver performance. Of course, the reality in our modern world is that situation and strategy can change from one situation to the next, so although our coaching is of necessity adaptive and dynamic, there are also underpinning fundamentals that provide the framework for why we do what we do.

The first of these fundamentals is that people always perform better when they are working from their strengths. Second, as defined by Revans’s axiom, the rate of learning in the individual and the organization must always be greater than, or at least equal to, the rate of change in their environment if they are to survive and thrive. Third, by maximizing the dynamic intersection of strengths, strategy, and situation, we will enable people to deliver the performance that is needed to succeed in our ever-changing world. The world that the Hi-Pos will inherit is replete with perils and pitfalls, but also possibilities and potential. Like Virgil guiding Dante through the Divine Comedy, our role is to help them navigate this world as best they are able, for the Hi-Pos’ stewardship of their organizations for future generations will have an impact on us all.

Professor P. Alex Linley, Capp, is a chartered psychologist and founding director of Capp (www.cappeu.com). He works as an organizational consultant applying strengths psychology to organizational development and people practices, serving a range of major global clients. Alex has written, cowritten, or edited more than 150 research papers and book chapters, and seven books, including Positive Psychology in Practice (Wiley, 2004), The Strengths Book (CAPP Press, 2010), and the Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Work (Oxford, 2010).

Nicky Garcea, Capp, is a chartered occupational psychologist and advisory director of Capp (www.cappeu.com), where she leads the advisory team delivering work in Capp’s key areas of assessment, development, performance management, and change. Her own areas of specialty include organizational development, strengths-based talent management, coaching, and female leadership development. Nicky has delivered work in the Americas, Europe, and West Africa. In 2010, she coedited the Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Work.

Notes

1. C. S. Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (New York: Ballantine Books, 2007).

2. P. R. Clance and S. A. Imes, “The Impostor Phenomenon Among High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention,” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 15 no. 3 (1978): 241–247.

3. J. Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . and Others Don’t (New York: HarperCollins, 2001).

D. Vera, and A. Rodriguez,-Lopez, “Strategic Virtues: Humility as a Source of Competitive Advantage,” Organizational Dynamics 33 no. 4 (2004): 393–408.

4. Further information on the Realise2 Team Profile is available from: http://www.cappeu.com/Realise2/TeamProfile.aspx.

5. Further information on the Realise2 4M Model and Realise2 strengths assessment tool is available from: http://www.cappeu.com/Realise2.aspx.

6. L. S. Lyons and A. Bateson, “How to Crack the Toughest Leadership Challenge of All,” A Lyons-Bateson Summit Paper (2009), www.lslyons.com.

L. S. Lyons and P. A. Linley, “Situational Strengths: A Strategic Approach Linking Personal Capability to Corporate Success,” Organisations and People 15 no. 2 (2008): 4–11.

L. S. Lyons, The Situational Intelligence Tetrad (Lyons-Bateson Reference Model), in The Coaching for Leadership Case Study Workbook: Featuring Dr. Fink’s Leadership Casebook (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012).