CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

COACHING HIGH-POTENTIAL WOMEN

Using the Six Points of Influence Model for Transformational Change1

Recently I spent the weekend with my husband at our favorite seaside resort. We had stopped at a local market to pick up a few last-minute items when I eyed a postcard display of pithy sayings and began to entertain myself. There was one in particular that grabbed me. It asked the question: “Are you one of those folks who, when opportunity knocks, you respond, ‘Can somebody get that?’”

I can’t tell you how many women leaders I have worked with who have struggled to find the right response to this knock of opportunity. Why? Why is it so hard for women to fully embrace and engage in possibility? I have coached many women, some of whom, struggling with a crisis of self-confidence, find themselves reluctant to believe in or accept new opportunities when they are offered and others who find it difficult to believe that they can engage in an old and familiar situation in a new way. And then there are the brave few who actively seek out these precious points of entry or opportunities for engagement only to find themselves waiting endlessly for someone to let them in. This chapter presents a model for transformational change that is a key resource for addressing and mastering challenges such as these.

To ask “Why?” is especially timely; for example, in the United States the workforce is undergoing a radical change. Baby Boomers, 60 percent of whom are white males, are beginning to retire. They are being replenished by a brand-new labor force that has the potential to revitalize and rejuvenate the system. Women are projected to account for 51.2 percent of the increase in total labor force growth between 2008 and 2018.2 This opens up more opportunity for high-potential women.

Consequently, it is a critical time for women to populate the workforce in such significant numbers, especially as they are overwhelmingly responsible for consumer buying decisions. In the United States, women make 85 percent of consumer purchases and influence decisions in more than 90 percent of all goods and services sold. As business futurist Faith Popcorn said, “The companies, from Fortune 500 to mom and pops to startup entrepreneurs, that do the best job of marketing to women will dominate every significant product and service category.” 3

This points to the inevitable realization that having women in leadership and decision-making roles in the organization is vital to reaching consumers and anticipating their needs. Those organizations that effectively serve their most important customers clearly have to know them well. And, who better to understand the choices, likes and dislikes, of women customers than women themselves?

Identifying and nurturing these new women leaders is critical, and this brings us to the next call to action: if organizations are to be successful, they must figure out how to recruit, sustain, and involve high-potential women at every level of business.4 This insight is supported by recent McKinsey research, which reveals that companies that promote women to high levels are the most profitable. McKinsey’s 2010 report on women showed that companies with higher numbers of women in their executive committees outperformed other companies, earning up to 41 percent higher returns on equity.5

Ascending the Corporate Ladder

With women having such potential to smooth the transition from Baby Boomers to New Workforce, we must ask: How are we doing? Are we making sure that women are ready for organizational life—and that organizations are ready for them?

It is evident from the increasingly growing numbers of women entering MBA programs around the world that women are acknowledging their commitment and desire to prepare to enter the world of business. In an April survey, thirteen of fourteen Forte member schools said that China or India accounted for the largest number of overseas women in their classes. Members in the Forte group include Harvard Business School, University of Chicago, and University of Pennsylvania.6

The question becomes: are we actively planning to develop these high-potential women who might be prepared and willing to assume more senior positions of leadership? That seems to differ depending on culture or country. The statistics in the United States suggest that there is more work to be done. Management and professional roles are currently split roughly equally between men and women. Yet, women are concentrated at the base of the hierarchical pyramid, whereas men occupy the upper levels. Only 14 percent of Fortune 500 officers are women, and—remarkably—less than 2 percent ever make it to the CEO level.7 This suggests a developmental opportunity for these U.S.-based organizations. In sharp contrast, women now hold 34 percent of senior management roles in China, excluding Hong Kong.8 That said, this seemingly enlightened progress is tarnished by the fact that many of these women remain unmarried in their mid-thirties and older and are perceived as shengnu, or “leftover women.”

As they ascend the corporate ladder, many working women find they suffer from directional challenges. Partnerships, marriage, motherhood, and community often vie with work responsibilities, thereby making it difficult to juggle the competing demands and desires of work and a personal life. Most women will recognize the sense of being overwhelmed by multiple roles.

For high-potential women, the pressure is especially intense. While working their way up their organizations, they find that their prizes come at a price. They tackle the challenges of new responsibilities and stretch assignments. They don’t want to disappoint the people who have championed them as they climb the ranks at work; furthermore, they don’t want to give up their competitive standing, nor do they want to disappoint family and friends. The clash between their personal and professional visions intensifies as they strive to navigate across and between two very different worlds.

So, why are all these women getting stuck, and how can they avoid the pitfalls? How can organizations best cultivate the talents of this elite and critical workforce?

The Six Points of Influence Model for Transformational Change

The Six Points of Influence Model for Transformational Change (Six Points Model) is a systemic coaching model used for breaking big changes down into manageable parts. It is especially pertinent in cultivating and coaching talent and has been effectively applied to the challenges that high-potential women now face. The unifying goal when using the Six Points Model is to support sustainable transformation.

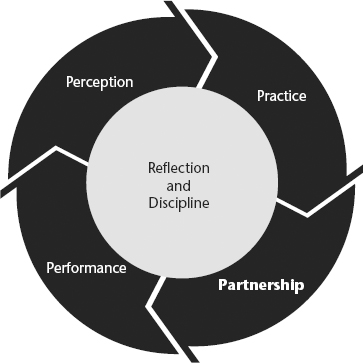

Within the model there are four interactive components (the Four Ps): Perception, Practice, Partnership, and Performance. Due to its systemic nature, a change around any of the Four Ps potentially affects the other three. The success of mastering any of these four components is achieved through using a balance of Reflection and Discipline. All told, these elements comprise the Six Points of Influence for Transformational Change.

Defining the Six Points of Influence

Perception

Perception is how we see ourselves, how we see others, how others see us, and how all involved see or understand the situation, business, or experience that has our attention.

Practice

Practice is what we do, our habits, our patterns of behavior. It is the set of competencies we choose to focus on. It is the way we deal with the change, our reaction to it, and our choice of how to engage.

Partnership

Partnership is the way we choose to engage dynamically with others and perhaps more importantly, it is the way we teach them to engage with us.

Performance

Performance is the actuality of how things unfold compared to the vision we want to create through the change.

Reflection and Discipline

To use the Four Ps successfully, leaders must integrate them with reflection and discipline.

Reflection is the time we spend considering the what-happeneds and the what-ifs? It holds the memories and emotions garnered from our experiences, and our understanding of the past—as well as our anticipation, both positive and negative, for how the change will affect things moving forward. All of these thoughts influence our decisions and the decisions of others, all of which affect what comes next.

Discipline is commitment combined with ability to stand up and take action.

A balance between discipline and reflection is necessary for success even though the natural tendency, when feeling stressed or threatened, is to ground oneself in one over the other. Reflection without action gets you nowhere, and action without reflection can result in hurtling at warp speed toward disaster.

Reflection and discipline are not exclusively solitary pursuits. They must also take place within the context of relationships with the principal people in the leader’s life. A coach’s responsibility is not only to work with the individual in developing an action plan, but also to ensure that the leader involves appropriate stakeholders. Developing a feedback loop with those stakeholders is bound to keep things on track.

Finally, for transformational change to stick, the envisioned outcome must be anchored in the values of the individual(s) embarking on change. The high-potential leader has to uncover her own values, both organizational and personal—a process that is often accomplished with the help of a coach—so that she can answer the so what? question. So what if I make this change? She must reflect on her personal perceptions and consider what it means for her, for her boss, organization, partner, family, and so on. Before she decides whether a change is worth making, the high-potential should consider the upsides and downsides for all the people in her circle of influence.

FIGURE 31.1. THE SIX POINTS OF INFLUENCE MODEL FOR TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE

Getting Started with the Six Points of Influence

Let’s recall for a minute our high-potential leader who hears opportunity knocking but is somehow stopped from opening the door. How can she apply this model? Imagine, for example, that the opportunity is the possibility of filling the vacancy her boss will leave now that he has announced he is moving on.

To start using the Six Points Model, the coach should introduce her to the Six Points: perception, practice, partnership, performance, reflection, and discipline. The high-potential should choose in which area she feels most comfortable beginning. If she struggles with the way she sees herself and the way she’s seen by others, she may shy away from applying for the job because of her lack of confidence. In that case, she would want to begin coaching on the Perception “P.” If, on the other hand, she were concerned that she didn’t have a clear vision for her team, she might choose to begin with the Performance “P.”

Using the Six Points of Influence to Accelerate the Hi-Po’s Career Path

A lack in any of the six areas can prevent high-potentials from being promoted. Let’s consider how the Six Points affect common obstacles that these leaders face when trying to break through the infamous glass ceiling and how the leader along with her coach can work to move them aside. Sometimes these obstacles relate solely to one of the points and sometimes they tie into two or more of the points.

Too many roles: Directional challenges from trying to be everything to everybody. This is a problem of perception, failing to have a clear vision for herself in a chosen role, and practice, constantly taking on more tasks and failing to be disciplined in drawing boundaries.

Boys’ club: Being excluded from a heavily male environment. This can be avoided by reflecting on one’s stakeholders, identifying key players, and cultivating partnerships.

Succession planning bias: Being overlooked. The culprit may be other people’s perceptions, as women are often seen as support people rather than leaders, or because male leaders assume that a woman wouldn’t want to be away from home to fulfill the added travel and responsibilities of stretch assignments. Senior management often lacks women, who might be likelier to propose other female candidates.

Always settling for support roles: Care-giving habit is deeply ingrained. This is usually due to perception, especially self-perception. The leader must be disciplined to reflect regularly on what she gives her time to. Will this create the legacy she wants to leave?

Going it alone: Too few alliances. Women have many reasons for going it alone. This may be due to the practice of trying to be perfect and avoiding asking for help or delegating to others. Women are culturally taught to do for others, so often a female boss takes it upon herself to pick up her team’s slack. Insisting on doing everything solo could also be because of insufficient partnerships, or a worry about perception. What will other people think of her if she asks for help, or doesn’t know the answer to every question? Some women worry that their coworkers will think they’re unprepared or incompetent if they work with a coach, sponsor, or mentor.

Cloudy vision: One example of cloudy vision is when a high-potential leader wants more than what she has settled for. She knows she can contribute in a stronger and more meaningful way yet doesn’t have a clear sense of what that vision or contribution might be. Or when she does have that vision but it conflicts with how her boss believes her work should be measured. These are both challenges of performance.

Case Illustrations of the Six Points Model at Work

Having described the model and provided some examples of how to identify and master obstacles and challenges, let’s explore how I coached two high-potential women leaders to create sustainable transformational change in their lives using the Six Points Model.

Greta and Donna

In the first case, Greta heard the knock of opportunity yet was resistant to answer the door. She was afraid that it would be disruptive to her family. In the second case, Donna was also challenged by the faint knocking of opportunity. The uniqueness of her situation was that she was not ignoring others, but herself.

Case Study #1: Greta’s Story

Greta found herself in a situation familiar to many women: torn between her family and career. Because she was a high potential (Hi-Po), the career opportunities were especially enticing. When Greta learned that she was short-listed to be the next CEO of one of the world’s biggest manufacturing companies, the validation she received was like the rush of endorphins that one can get during exercise, making her feel energized and strong. For high-potentials, their expanding sense of capabilities and this validation from others can be addictive. It is easy to overindulge in a can-do campaign only to wind up disappointing oneself by making mistakes in one’s personal life. As Greta was given more stretch assignments in preparation for her new role, her concerns mounted. She realized she could not continue at this accelerated rate while maintaining all her other commitments and responsibilities.

The tipping point came when she was assigned a new project that would require frequent travel out of the country. Not even Greta could stretch herself this far. She needed to rethink and renegotiate her ideals for herself and her family. She turned to her coach for help. We reflected together on the so what factor. We considered what new behaviors she would adopt and actions she might take. We considered the upsides and downsides to the changes and proactively prepared for both. Greta completed the following sentence: “If I take on this new assignment then I _____________?” She filled in the same sentence with the names of her various stakeholders, considering the impacts on her husband, family, team, and organization.

Greta set aside some quality time to meet with her husband and kids. Together they reflected on the sacrifices and added responsibilities everybody would have to shoulder, and assessed whether the promotion was worth it. They examined the short- and long-term rewards, and the financial upsides for the family: more security, money for college, and family vacations.

The deal-clincher was when Greta told her family that if she was successful on the assignment, she would split her large bonus with them. Now everybody was working together for the bonus, rather than sacrificing while she alone reaped the rewards. This created a marked difference in their partnership. The kids enthusiastically discussed a strategy and divvied up the extra chores and responsibilities they would take on during Greta’s absence.

Greta also engaged in reflecting with her boss about her visioning process. She shared her perceptions and concerns about the upsides and downsides. Greta showed discipline (that is, capability and commitment) when she negotiated with her boss, and was able to secure at least ten days home out of every month. By working with her family and her boss, Greta set realistic expectations and received support from inside and outside the organization. She was able to come up with a plan that had a beneficial impact on all the key players: her current team, the company, and her family.

Case Study #1: Action Steps

Perception: Greta needed to reflect on her beliefs. She had to decide if her new role held real value and was worth the sacrifices. She also had to overcome traditional female concepts, such as perceiving her value through her support of others.

Performance: Once she had clarified her vision and anchored it to her values, Greta realized she was trying too hard to be everything to everybody. She had to change her practices, no longer trying to be all things to all people and seek support. She expanded the reflection process to include her primary stakeholders.

Together they discussed pros and cons and formulated a common vision.

Discipline: The coach helped to achieve this by supporting Greta and holding her accountable for executing a strategy that would align her practices and her vision.

Practice: The family devised an action plan defining expectations and responsibilities. This included details such as who would be responsible for which chores, and how the bonus would be split.

Partnership: She set up a process for continuous feedback, to make sure the arrangement was working for everybody, and to provide a means for continuous improvement.

Case Study #2: Donna’s Story

Donna worked for a large health care organization. She began as an administrative assistant and, over a thirty-year career, worked her way up the corporate ladder to be head manager overseeing services and support. Although this was a high rank, she had always worked in support positions and even as a manager was still in a service-oriented department.

Donna’s niche seemed natural to her, as it reflected what she observed in her early life. Donna’s mother was a renowned hostess who made everybody feel loved and cared for. In her job, Donna found herself valued for filling a similar role. Like her mother, she was adept at navigating relationships and making sure everybody was comfortable and happy.

But Donna secretly yearned to work in a role involving creativity and innovation. Because she had only shown off some of her talents, she was slotted into a track that allowed for little creativity. She did well in her position, keeping quiet about her other talents because she believed her company valued her for her ability to execute other people’s plans, not to formulate her own. Every time she had a performance review and was asked about her interests and next steps, she concealed her true desire. She assumed that, since her coworkers already held a strong perception of her in her current role, that her desire to refocus on innovation and strategy would not be appreciated, acknowledged, or even viable. Donna had fallen into the trap that many high-potentials do of failing to reflect on her own self-limiting beliefs. Traditionally, women have been valued for supporting others. Putting oneself first is not in the female lexicon. Many women leaders question whether it’s right to prioritize their own needs and desires.

Donna needed to change her perception of herself, and to teach others to change the way they viewed her. During coaching sessions, we worked on bringing out Donna’s hidden facets. She had to change her practice of staying silent in strategy meetings. After many years of only speaking up about issues related to her ability to execute on other people’s plans, she had to exercise discipline by finding the courage to voice her ideas and show her capacity for innovation.

To make this shift, Donna learned to traverse the territory of partnerships. She did her research, identifying key players in the company who were involved in strategy and innovation. She prepared for moments when she could connect to these potential supporters, either in formal situations like strategy meetings, or informal chance meetings in the elevator. She practiced how she would share ideas that exposed her creative and innovative side.

Donna’s rebranding campaign changed her perception of herself, and how others perceived her. Instead of sitting back in silent support, she focused on new competencies of communication and influencing others. By being willing to take a risk and put ideas out there, she demonstrated her strategic side and taught other people to look at her as a resource.

Donna’s work paid off. She won over her boss, who is currently championing her efforts and helping her find an opportunity on the innovation and strategy side.

Case Study #2: Action Steps

Reflection: We reflected on what Donna valued most. We addressed her fears about changing her perception and performance, and understanding the obstacles to her self-confidence.

Practice: We used her practice to change people’s perceptions. In this case, that meant preparing her strategies and finding the courage to voice them during meetings and in informal settings. We honed her ability to influence others.

Partnerships: We identified key players who could help her get where she wanted to go. It’s crucial for coaches to help their clients determine who will stand in support, and who’s going to obstruct transformation. High-potential women leaders must learn how to engage their potential champions.

High-potential women and their coaches have exciting opportunities to influence the world and expand the way that women are perceived. As Baby Boomers retire and workforce statistics shift, women will be called into more leadership roles. Coaches must be sensitive to these leaders’ unique needs, and be prepared to help them overcome the obstacles that stand in their way. They must understand that women’s self-perception and others’ perceptions of them have been constrained by culture, impacting their courage to envision the possibilities. As more high-potential women and the organizations and leaders they work with step up to the responsibility of examining the areas of perspective, practice, partnership, and performance, and combine this examination with healthy doses of reflection and discipline, we will see more executive roles being filled with smart and savvy female leaders.

To any leader who (1) has experience and understanding for the challenges presented and (2) resonates with the Six Points of Influence Model and the possibilities it creates, let me offer you the ultimate challenge in the form of two remaining questions:

1. What can an individual leader within an organization do to create momentum for propping open doors?

2. What do organizations need to do to prop open more doors for high-potential women?

Or, in the words of Rabbi Hillel some two thousand years ago,

“If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”

“If I am only for myself, what am I?” and

“If not now, when?”

Barbara Mintzer-McMahon is an executive coach and consultant who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. She specializes in leadership development, team building, change management, and strategic partnerships. In 1989 she founded the Center for Transitional Management. She was senior lead for the coaching faculty for the Global Institute for Leadership Development for Linkage Inc. from 2003 to 2011. She has keynoted and developed training programs for Shell International, Intel, Pella Corp., Nektar Therapeutics, University Polytechnic Madrid, and many others. Ms. McMahon is partnered with Alexcel and Institute of Executive Development researching Best Practices of Executives in Transition. She is frequently called on to speak and consult on this topic.

Notes

1. The Six Points of Influence Model for Transformational Change (formerly called the Four Ps Model of Coaching) has been developed by Barbara McMahon through her practice as an executive coach over the last thirty years.

2. http://www.dol.gov/wb/stats/main.htm. Accessed July 24, 2011.

3. Faith Popcorn, EVEolution: The Eight Truths of Marketing to Women (New York: Hyperion, 2000).

4. For the purposes of this article, I will use the following definition of high potential by Jay Conger, Douglas Ready, and Linda Hill, “High potentials consistently and significantly outperform their peer groups in a variety of settings and circumstances. While achieving these superior levels of performance, they exhibit behaviors that reflect their companies’ culture and values in an exemplary manner. Moreover, they show a strong capacity to grow and succeed throughout their careers within an organization—more quickly and effectively than their peer groups do.” http://hbr.org/2010/06/are-you-a-high-potential/ar/1 accessed July 24, 2011.

5. McKinsey Company, “Women Matter” report, 2010. http://www.mckinsey.com/careers/women/insights_and_publications/women_matter.aspx.

6. Demast, A. “For Chinese Women U.S. MBAs Are All the Rage,” Bloomberg Business Week (May 5 2011).

7. 2010 Catalyst Census: Fortune 500 Women Executive Officers and Top Earners. http://www.catalyst.org/publication/459/2010-catalyst-census-fortune-500-women-executive-officers-and-top-earners.

8. Demast, A. “For Chinese Women U.S. MBAs Are All the Rage.”