FOREWORD

A Brief Trek Toward the Next Agenda for Coaching

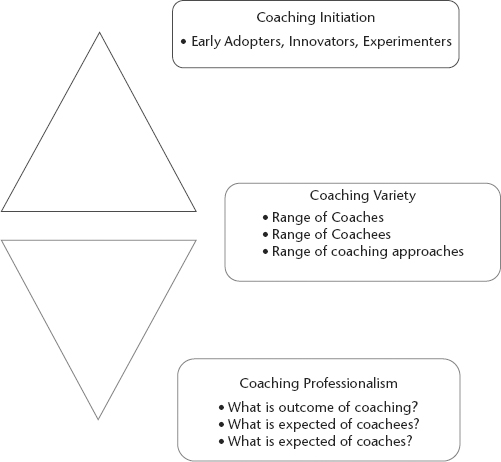

Like many professions, business coaching began in bits and drabs with individuals here and there being and using coaches. In the last twenty years, as use of business coaches has mushroomed, the range of coaching expectations and services has exploded, for both the good and the bad. I believe that most change efforts like coaching go through the flow depicted by a diamond (Figure I.1). At the top, the early adopters, innovators, and experimenters (like Marshall Goldsmith and other authors in this volume) begin with a zealot’s passion and great anticipation. As the field evolves, the widest part of the diamond depicts a host of coaching alternatives ranging from users of coaching who want to join the bandwagon but are not committed to change, to coaches who are passing from one job to another without a serious attempt at coaching rigor, to those want to increase the professionalization of the coaching movement. But, as the field evolves, coaching moves to the bottom part of the diamond, where rigor and clarity begin to emerge around three issues:

FIGURE I.1. EVOLUTION OF THE COACHING MOVEMENT TO A PROFESSION

1. What are the outcomes of coaching?

2. What are the requirements of one being coached?

3. What are the skills of an effective coach?

In this volume, Marshall, Laurence, and Sarah have done a marvelous job sourcing material from thoughtful coaches and observers of coaches about these important questions. With these answers, coaching will move down the diamond to become a more rigorous, relevant, and professional endeavor. Having had the privilege of previewing these outstanding essays, let me synthesize the messages they offer (with some of my flavoring) on these important questions.

What Are the Outcomes of Coaching?

One of my shortest and most memorable coaching experiences was with a high-potential family member on an executive team. I was honored to be invited to coach him as he prepared for his likely succession to run a large family business. When we began our conversation, I asked why he wanted to be coached and what he wanted out of the experience. He seemed surprised by the question and replied in an off-hand manner, something like, “I just need to tell the board that I am being coached by someone reputable so that I can be seen as ready to move into my next leadership role.” When I probed what he wanted in terms of business or personal outcomes, he deferred to me, saying, “You tell me.” It was not a long engagement. He was not ready to be coached and was totally unaware of the outcomes of coaching.

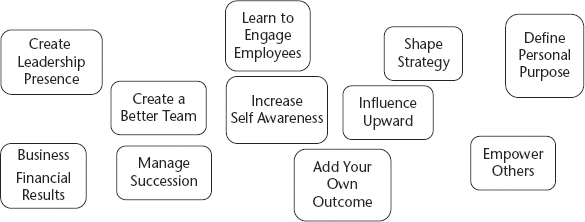

Individuals and companies engage in coaching for a host of reasons that often seem disconnected and disjointed:

These outcomes are well discussed in the chapters throughout this book with great examples and definitions of what coaching can and should accomplish.

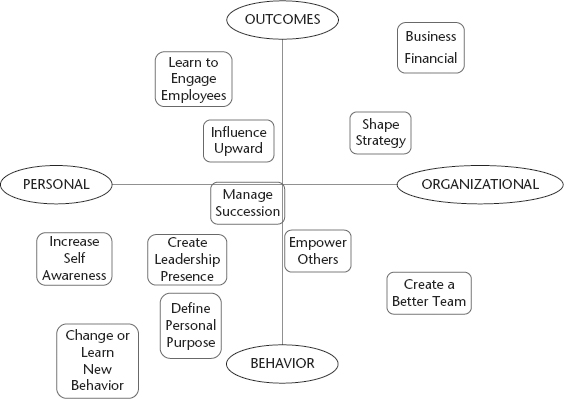

As the coaching profession moves forward (down the diamond), it will become increasingly important to create a more rigorous typology of coaching outcomes that are not subject to the whims of the coachee, the coach, or the organization contracting for coaching. Let me offer a possible typology of coaching outcomes based on two dimensions: [1] does the coaching focus primarily on changing behaviors or on delivering results and [2] does the coaching focus more on the individual or the organization? With these two dimensions in mind, the coaching outcomes above might be categorized in Figure I.3. As coaching evolves to more professional standards, having clear outcomes will help the individual being coached know why she or he is engaging in coaching. It will help the coach have clear expectations so that the engagement can be monitored and monetized. It will help the sponsoring organization recognize the value of the coaching investment. This set of essays clearly articulates these potential coaching outcomes.

FIGURE I.2. DISJOINTED COACHING OUTCOMES

FIGURE I.3. A TYPOLOGY OF COACHING OUTCOMES

What Are the Requirements of the One Being Coached?

In the above case of coaching calamity, the individual was not ready to be coached. There are two broad issues relevant to the coachee.

First, who can and should be most open to coaching. This volume offers marvelous examples of when and for whom coaching might be most appropriate, for instance:

- Business leaders facing new and unforeseen business challenges who may require new behaviors

- Leaders throughout the company who may have a derailer behavior or style that keeps them from accomplishing what they desire (e.g., lack of self-awareness or ability to influence upward)

- Leaders who have had little exposure to or experiences outside their home organization

- Professionals (e.g., law students) who must have both emotional and social skills as well as technical expertise to succeed in their career

- High-potential employees who need to refine skills to prepare for future career opportunities

Coaching may be adapted to each of these target groups and offer the outcomes summarized above.

Second, obviously, the individual being coached has to be open to change. Every good coach I know has walked away from an engagement because the commitment of the coachee was not adequate for the change required. This volume lays out “tells” or “signals” to look for in the prepared coachee:

- Open to change

- Willing to experiment with ideas

- Able to reflect and acknowledge mistakes

- Willing to listen to what others say with a sense of inquisitiveness and humility

- Open to learning

- Focused on the future (feed forward) rather than the past (feedback)

- Able to adapt a style to the requirements of the situation

- Has a sense a personal mission and passion

Not all coachees will ever be fully prepared for coaching, but they should be aware that it is more than casual conversation and dialogue; it is serious and hard work to reflect, define behaviors, identify required behavior changes, and sustain those changes. It means a candor and openness that many hard-core and hard-shelled executives don’t want to admit or face.

But, as the joke goes with psychologists (how many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb. . . one, but the light bulb has to want to be changed), so it goes with coaching. Unless and until the coachee is open, receptive, and willing to invest, the experience won’t work well.

We may need for the profession a prescreening test for those who want to contract for coaches so that they recognize the commitment required of them to engage in the effort.

What Are the Skills of a Good Coach?

There are many types of coaches. This volume suggests that leaders, peers, HR professionals, social networks, and external experts can all participate in some form of coaching. Each role may have different coaching outcomes, but there are some common coaching skills that are required for anyone who wants to coach.

I know coaches with all kinds of styles: some are extroverts, others introverts; some are intuitive, others data-driven; some focused on cognitions, others on feelings; some who see the big picture, others who revel in details. Coaching style is not as important as following some guidelines on both the content and process of coaching. Again, the essays in this volume offer wonderful tips and insights as to how to be a more effective coach through both content and process.

Content means that the coach has a point of view about what it means to be an effective leader. This point of view is likely to be tied to the situation of the organization’s business context, strategy, and team and to the gender and background of the individual being coached, but the coach needs to have a mental model about what makes an effective leader. In a clever essay, Sarah McArthur argues that when ideas are put into writing, they become clearer. It may be useful for coaches to craft their views about what makes an effective leader. Once they know their personal views, they may be better able to help the person they coach define their personal leadership point of view.

Process refers to the engagement between the coach and coachee. Again, the collective wisdom of these thought leaders offers some tried, tested, and true suggestions for managing the coaching engagement. Let me summarize some of what is talked about:

- Focus on the future, not the past (feedforward)

- Build a trusting relationship where the coachee knows you care about him or her as a person

- Recognize, discover, and build on the passion, meaning, and desires of the coachee

- Listen for understanding

- Ask probing questions that surface deeper issues

- Respect and build on the strengths of the coachee, but do not hesitate to label and run into the weaknesses

- Be candid without being punishing

- Use data from many sources (e.g., 360) to help the coachee recognize unintended consequences

- Find the right physical setting to coach

- Use time wisely (not too much or too little)

- Build sustainability into the coaching engagement by follow up and accountability

- Be very sensitive to unique qualities (e.g., gender, religious orientation, global experience, personal history) of the coachee and be open to talk about these sensitive areas

I was privileged very early in my career to observe Bill Ouchi, an incredible mentor and advisor, coach a senior business leader for two hours. I was able to see him create a professional and personal intimacy where the business leader put down his defenses and was able to hear Bill’s thoughtful and caring counsel. Coaches need to pay attention to the process of coaching and nurturing those they coach, and then consulting, as appropriate, to build the organization infrastructure to sustain the personal changes.

Conclusion

Investments in coaching show few signs of slowing down. Hopefully, it is not another fad in the management heritage of fads. Coaching may shift from a movement to a profession with discipline and rigor around three questions:

1. What are the outcomes of coaching?

2. What are the requirements of one being coached?

3. What are the skills of an effective coach?

This outstanding volume offers thoughtful, innovative, and applicable insights on each of these questions. This is a trek worth pursuing!

Dave Ulrich