The March West, 1874.

1 | Mayerthorpe

ON THURSDAY, MARCH 3, 2005, the worst case of police mass murder in the history of Canada took place near Mayerthorpe, Alberta. On that day, a disturbed lone gunman ambushed and murdered four young members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police with a semi-automatic assault rifle that killed them all within a matter of seconds.

There is tragic irony in the fact that such a dreadfully momentous event should be associated with a place like Mayerthorpe, a small and obscure rural town located on Highway #43 about 145 kms (87 miles) northwest of Edmonton.

In fact, this tragedy didn’t really happen at Mayerthorpe at all but out in the countryside much closer to the rural hamlet of Rochfort Bridge, a tiny crossroads community of sixteen houses and one restaurant located in the county of Lac Ste. Anne.

The reason this atrocity will forever be associated with the town of Mayerthorpe is that three of the four slain policemen were members of the Mayerthorpe RCMP Detachment.

There have been other cases of multiple police murder involving the RCMP. Thirteen were killed during the Second World War, but that was over a period of years. Eight were killed in the rebellion of 1885, but that, too, happened in armed conflict and took place over a span of three days.

Five RCMP members drowned in Lake Simcoe in Ontario in 1958 while on a late-night investigative mission to Georgina Island; their small boat capsized in the turbulence of a sudden storm. In 1963, four Mounties died in a plane crash at Carmacks in the Yukon.

In 1962, Constables Joseph Keck, Gordon Pedersen, and Donald Weisgerber were gunned down at Kamloops, British Columbia.

On several occasions, two Mounties have been murdered at the same time. In 1970, Sgt. Robert Schrader and Cst. Douglas Anson were shot to death while responding to a domestic dispute near MacDowall, Saskatchewan. The same fate befell Cpl. Barry Lidstone and Cst. Perry Brophy at Hoyt, New Brunswick, in 1978. Constables Robin Cameron and Marc Bourdages were shot and killed by a lone gunman near Mildred, Saskatchewan, in July 2006.

The March West, 1874.

But Mayerthorpe retains the dubious distinction of being the worst case of multiple murder in the modern history of the RCMP.

What’s more, it is also a fact that the Province of Alberta is disproportionately represented on the official RCMP Honour Roll that lists all the Mounties who have died in the line of duty.

To date, thirty-nine of the 220 members on the Honour Roll have died in Alberta. This amounts to 18 percent of all the Mounties who have died in the line of duty across Canada since the inception of the Force.

This high percentage can be partially explained by the fact that the Mounties have been stationed in Alberta longer than anywhere else in Canada. The Force was initially organized as the Northwest Mounted Police in 1873 to help keep the peace in Canada’s North-West Territories, which at that time encompassed the District of Alberta. The major incident that spurred the formation of the NWMP was the massacre of twenty-five Assiniboine Indians by wolf hunters and whisky traders in May 1873 in the Cypress Hills close to the Alberta eastern border.

In July 1874, a contingent of 275 of these Mounties began their famous “March West” from Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, and ended their western trek by establishing their headquarters at Fort MacLeod in southern Alberta. The Force was then divided in two, with half of the redcoats travelling north to Edmonton. The following year, Fort Calgary was founded.

Ever since 1874, the Mounties have policed Alberta. In 1905, when Alberta became a province, the Mounties, in essence, became Alberta’s provincial police. And the massive size of the province makes that a challenging task.

Alberta ranks as the fourth largest province in Canada after Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia. It is a land mass only slightly smaller than the State of Texas, extending 1,223 kms (760 miles) from Montana in the south to its northern border with the Northwest Territories. From east to west, Alberta’s maximum width is 660 kms (410 miles).

The only areas in the province that the Mounties do not police are some of the big cities like Edmonton, Calgary, Lethbridge, and Medicine Hat. A few smaller communities such as Camrose and Taber also have their own police service.

Consequently, throughout Alberta there are 2,200 Mounties stationed in 107 detachments, from Waterton Park on the Montana border to Assumption, just below the southern edge of the Northwest Territories.

In 2005, Mayerthorpe had eleven members working in its detachment office, two of whom primarily worked traffic control on busy Highway #43.

Two other nearby communities that play a significant role in this story also have RCMP detachment offices. Whitecourt, a town of 8,500 situated on Highway #43 just north of Mayerthorpe, had a twelve-member unit. Barrhead, to the east of Mayerthorpe with a population of 4,600, had nine Mounties working in their detachment. Although Barrhead has a bigger population than Mayerthorpe, the latter detachment has more demanding highway responsibilities.

Mayerthorpe sits quietly north of the densely populated Calgary–Edmonton corridor, where it is nestled among the rolling hills and widespread rural properties of central Alberta.

The town began its existence in 1919 with the building of a small Merchant’s Bank of Canada on “Main Street.” That was soon followed by the erection of Crockett’s General Store and a small hotel. As a fledgling village, the community got its name from Robert Mayer, the first postmaster in the area, and from the suffix “thorpe,” an archaic Old English term meaning “little village.”

It was officially incorporated as a village in 1927 and has sustained its existence since then by providing agricultural goods and services to local farmers. Today, with a population of 1,600 it also serves as a bedroom community for the lumber mills in Whitecourt and nearby Blue Ridge.

Although the town’s weekly newspaper, The Mayerthorpe Freelancer, was closed in 2008, the essence of the community can be best understood by scanning some of the articles in its back issues:

Celebrating Agriculture in Alberta

Farm Safety

Calving Season Springs to Life

Alberta Angus Breeder of the Year

Preventing Farm Accidents

Our Greatest Asset is the Farm Family

The advertisements are equally revealing:

Farm to Fork with Alberta Pork

Silver II Custom Harvesting

The Dependable Bulls of the Towaw Cattle Company

Cunningham Fertilizers

Ditner’s Feed Service and Supply

Farms and Acreages for Sale

In 2005, the economy in Mayerthorpe was sluggish. However, there had been a time when the town was a bustling, thriving community supported by the sale of cattle, grain, and lumber.

But its commerce suffered a severe blow in 2003 when the threat of “mad cow” disease closed the U.S. border to Canadian beef and devastated the local cattle and trucking markets. That same year, the area suffered a major drought. Then, in 2004, the region was infested with grasshoppers that plagued the grain crop.

Since then, economic conditions have only marginally improved, but farmers, being a hardy and determined breed, have stayed the course and helped keep the town solvent.

The weather in Mayerthorpe is typically Canadian. Although the summers are warm and spring is usually pleasant, the winters there can be brutal. Temperatures of twenty below zero are common and there is usually at least one week every winter when the thermometer dips to thirty or thirty-five below. When this cold is combined with a nasty wind, the chill factor can become unbearable.

But the fall in Mayerthorpe is glorious.

Pastor Wendell Wiebe, the minister of the local Baptist Church and chaplain of the town’s volunteer fire department, says, “The fall colours here are amazing . . . beyond anything I’ve seen in the world. And that includes the Maritimes, the United States, and the Philippines.”

Living in a small community like Mayerthorpe has both its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the townsfolk enjoy the benefits of everyone being close and knowing about each other. When someone is sick or suffering, the news spreads quickly and the neighbours rally ’round to help. On the other hand, that same social intimacy has the potential for generating gossip. And that can be destructive.

In this regard, it is Pastor Wiebe’s observation that the people of Mayerthorpe are generally cautious and reserved. “I think that’s natural in a small town. Everyone knows everyone else and they have learned to be prudent . . . cautious . . . in their conversation. There’s a warm sense of family here but most folks are careful of what they say . . . and who they say it to.”

From a physical perspective, Mayerthorpe is unspectacular. Viewed from a distance, the town presents an unimpressive profile of low-lying buildings, including a downtown section comprised of four blocks of insignificant stores on either side of its one commercial “Main Street.”

The most imposing structure in the community is a huge grain elevator, no longer functional, that stands next to the town’s rusting railway tracks. Although the elevator is obsolete, it has been declared a historical site and is being retrofitted to its original condition when it was a busy commercial enterprise in the early 1960s.

Elsewhere in town, amid clusters of modest frame houses, there are schools, four churches, the twenty-eight-room Haven Inn Hotel, the Co-op and Super A grocery stores, a Canadian Legion, a fire hall, a Case Equipment dealership, the Lariat Restaurant, a community outdoor swimming pool, an eighteen-hole golf course, and a vacant lot where the old arena once stood. Sadly, it was lost in a fire in 2008.

The most attractive building in the community is the modern, dark-bricked RCMP detachment office that was opened in 1985 and sits on the edge of town near the highway. It’s a one-storey structure with offices, an interview room, a meeting/coffee room, a filing room, a communications area, and four cells for short-term stays.

In March 2005, the Mayerthorpe Detachment was run by Sergeant Brian Pinder, an experienced NCO. However, beginning on Monday, February 28, 2005, Sgt. Pinder had gone on a one-week holiday leave. Acting as commanding NCO in his place was Cpl. Jim Martin, thirty-eight, who had fifteen years’ experience and had been at the Mayerthorpe Detachment since September 2001.

Mayerthorpe is a friendly place. Most people who go there soon discover something warm and welcoming about the local people that they quickly come to appreciate.

It is, however, a place where nothing very exciting seems to happen . . . nothing of any real consequence.

But on Wednesday, March 2, some ordinary, rather minor events began to play out that would change the town’s image forever.

The day started out like any other. People showered, ate their breakfasts, and began going about their normal routines. Kids went to school, moms and dads went off to work, salesmen made their calls, folks at home listened to their radios.

Everyone in town was looking forward to the end of winter and the start of a new and rejuvenating spring. As the morning progressed, no one in Mayerthorpe could suspect that within twenty-four hours the name of their community would be known around the world.

That morning, bailiff Rob Perry phoned the Mayerthorpe Detachment and advised Cpl. Jim Martin that he was proceeding to James Roszko’s farm on Range Road 75 near Rochfort Bridge.

Perry told Cpl. Martin he was going there to execute a warrant authorizing him to seize a white 2005 Ford F350 Super Duty pickup truck on behalf of Kentwood Motors of Edmonton. The car agency had been unable to confirm Roszko’s credit status, and for two months Roszko had failed to reply to their repeated phone calls.

Perry also said that based on the information he had received about Roszko’s being aggressive and abusive, he decided to bring his partner, Mark Hnatiw, along with him for protection. Hnatiw was a huge man standing six feet, four inches and weighing 240 pounds; he formerly had been employed as a prison guard.

Cpl. Martin advised Perry to be careful, because Roszko had been charged last August for damaging the tires on the two different vehicles that had driven onto his property. One car belonged to a meter reader; the other to a census-taker.

Jim Martin had handled the census-taker’s complaint. It alleged that Roszko had damaged all four tires on her car. When Martin went out to investigate, he found that Roszko had made a spike belt by splitting a length of plastic plumbing pipe and embedding it with nails. Then Roszko laid the pipe down in front of the gate of the driveway leading onto his property.

Prior to the census-taker’s complaint, Roszko had used the same spike belt to flatten three tires on the meter reader’s vehicle.

When Martin went out and discovered the spike belt in Roszko’s laneway, he charged him with two counts of mischief. Now Martin was waiting to testify against him at an upcoming trial scheduled for the spring.

Martin also warned Perry to watch out for Roszko’s two vicious dogs that he often let loose to frighten unwanted visitors.

Peter Schiemann outside the Mayerthorpe Detachment, 2003.

Martin finished his conversation with Perry by telling him he would come out to assist him. Jim said he would leave right away and meet Perry at the gate of Roszko’s farm.

When the corporal got off the phone, he asked Cst. Peter Schiemann, twenty-five, to accompany him out to Roszko’s farm. They left the office quickly, got into a PC (police cruiser) and headed out of town toward Range Road 75.

En route, Martin radioed Cst. Julie Letal in her PC and asked her to meet him at Roszko’s place.

She responded “Ten-four,” and turned her cruiser towards Rochfort Bridge.

Jim Martin and Peter Schiemann chatted amiably as they drove out of town and turned right onto Highway #18.

Schiemann, who was tall and trim, was a pleasant and personable young man who loved being a policeman. He had graduated with flying colours from the RCMP Training Academy at Regina in November 2000 and was immediately posted to Mayerthorpe. Now, with more than four years of experience at the detachment, he was one of the senior constables in the unit.

Jim Martin says, “Peter was a really good cop. He was raised in a good family where he learned strong moral and ethical values.”

In August 2004, he was assigned to Traffic Services at Mayerthorpe. This meant he became part of a team that included three members from Whitecourt who would patrol long stretches of both Highway #43 and Highway #32 in the area of the two towns and beyond.

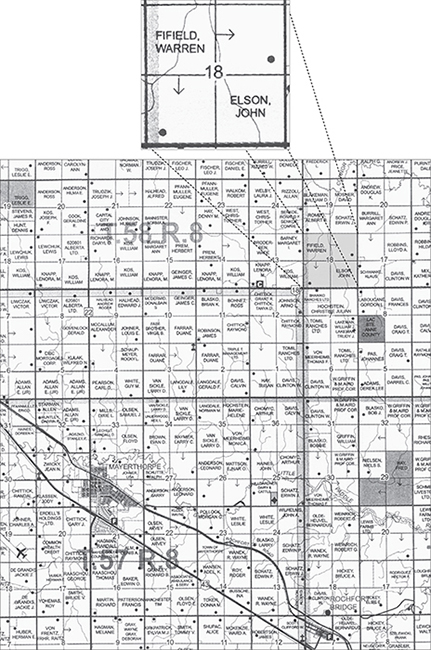

A partial plan of Lac Ste. Anne County showing the Fifields’ three-quarter section relative to Mayerthorpe and Rochfort Bridge. The dot on the left of the property indicates the location of the Fifields’ trailer; the dot on the right indicates James Roszko’s farmstead. (Lac Ste. Anne County Office)

The Fifields’ three-quarter section showing the Fifields’ trailer on Range Road 80 and James Roszko’s farmstead on Range road 75, plus the terrain, bush, and brush patches on the property. (Drawing by Magdalene Carson)

Martin says, “On the way to Roszko’s place, Peter and I talked about his recently being chosen for a special new ‘interdiction crew’ whose mandate was to target drug runners on the long stretch of highway to Grande Pairie. Peter had recently completed some projects at Jasper regarding interdiction and was looking forward to putting those theories into action. He was excited about that work. And he was very pleased with being selected for this special crew. Peter didn’t brag or anything, but I knew that his being chosen was a notch in his belt . . . a real feather in his cap.”

As they headed east along the highway, Martin briefed Schiemann on the task at hand.

Peter knew Roszko’s name and his reputation. Everybody in the detachment knew about James Roszko. But they also knew that Roszko posed no great concern for the members. Roszko had a reputation of being nasty and threatening with everyone — everyone except the police. Jimmy Roszko often acted like he was crazy but he was smart enough to know he could only go so far with the police. He could be loud and foul-mouthed and aggressive with them, but he never dared to threaten them.

Roszko’s farm on Range Road 75 was on part of his mother’s and stepfather’s three-quarter section, which equals 480 acres of land. His mother, Stephanie, and her third husband, Warren Fifield, lived in a mobile home on Range Road 80, which is the next road west of James’s. From their trailer, they could look north up the hill and see the back of James Roszko’s farm. The view from James’s hilltop property is delightful, with gently rolling farmland extending in a distant vista as far as the eye can see.

James Roszko’s place really wasn’t much of a farm. At the road, there was a locked gate across his laneway with a “No Trespassing” sign on it. The laneway ran about forty yards, and then there was another locked gate leading into his inner compound.

Inside the inner compound, there was a house trailer where he lived, an eighty-by-forty-foot steel Quonset hut where he worked, three 1,200-bushel galvanized steel granaries with conical tops, two gravity-drop gas tanks, a doghouse, and an old wooden shed at the southwest corner of his Quonset hut.

When Perry and Hnatiw pulled their black pickup to a stop in front of Roszko’s locked gate, they spotted him in front of the smaller, “human” door of the Quonset. He was wearing a black baseball hat, blue jeans, and a dark jacket. Roszko clearly saw them but didn’t acknowledge them. He turned and walked back into the Quonset.

Perry honked his horn several times but got no response.

Hnatiw says, “The next sighting of him was when he appeared by his pickup truck beside his house trailer. How he got there, I don’t know. I didn’t see him walking across the yard or anything.”

Shortly after that, Roszko let loose two large dogs, one of which looked like a Rottweiler. Barking and growling, they came charging toward the bailiffs, who quickly retreated into the safety of their pickup truck. Roszko then went into the trailer.

Roszko’s compound on Range Road 75. (Roszko’s trailer is in the position it was at the time of the killings.) (Drawing by Magdalene Carson)

An aerial photo of Roszko’s compound showing the patches of bush and brush and the terrain nearby. (RCMP)

“We called the police again, ’cause that’s when it started to get weird,” says Hnatiw. “Then Roszko comes out, gets into the white pickup and drives south through a gate; then he stops at another one.

“We thought he was going to leave that way, but he didn’t. He backed his truck up and came towards us and stopped at the inner chain-link gate. Then he let himself through the chain-link gate and before he got back in his truck he yelled at us, ‘Fuck off!’”

After that Roszko climbed back in his pickup and drove west across the frozen fields.

Just as Jim Martin was turning his PC left onto Range Road 75, he received a second phone call from Perry, who reported their experience with the dogs.

“Hang on,” Jim replied. “We’ll be right there. Don’t enter the property until we get there.”

A minute later, at 3:40 p.m., Martin and Schiemann pulled up beside the bailiffs’ truck.

After Rob Perry pointed out the direction in which Roszko had fled, Martin and Schiemann jumped in their cruiser and hurried away in an attempt to locate him.

Shortly after they left, Cst. Julie Letal arrived at the farm in her PC.

Martin and Schiemann sped south on the Range Road, had a quick look around Highway #18, surveying the yards of a few farms. Seeing no sign of Roszko, Martin headed north on Range Road 80.

Ten minutes before Martin and Schiemann made their turn north, Dianne Romeo, her daughter Buffy, her grandson Cooper Golden, her sister Dixie Mills, and her friend Crystal Loughran were out riding horses. Dianne and her husband, Bruce, own a spread immediately north of the Fifield property on Range Road 80. Dianne and her group had ridden north but now were returning south to the Romeos’ stable.

She says, “All of a sudden I heard this motor roaring in the distance ahead of us. Because of the rise on the road, I couldn’t see anything, but I knew someone was coming towards us at an awful clip.

“So we all edged over to the side of the road and I made sure my grandson’s horse was edged over there, too.

“Then Jimmy Roszko came flying over the hill in his white truck. He kind of spooked our horses. Normally he doesn’t drive like that . . . so fast and reckless.

“And it wasn’t long after he went by that a police car heading south stopped us and said he was looking for Jimmy Roszko. He asked if we had we seen him.

“We told him what we’d seen . . . and then another police car [Martin’s and Schiemann’s] came speeding up from the south and the officers in both cars had a talk with each other. Then they both drove away.

“We wondered what they wanted Jimmy for. But it was none of our business, so we finished our ride and unsaddled our horses. That was about it.”

When the two police cars separated, Martin decided it was more important that he and Schiemann return to the bailiffs at the Quonset hut. The other Mountie, Cpl. Jeff Whipple, continued his search for Roszko.

When Jim Martin and Peter Schiemann got back to Roszko’s place, they had a brief discussion with Perry, Hnatiw, and Julie Letal about what they should do next. All the while, the dogs kept charging around inside the fence, barking and baring their teeth.

Martin checked with Perry and determined he had a duly authorized court order that allowed them to enter Roszko’s property and permitted them to seize the Ford pickup truck.

The bailiffs said that Roszko might have fled the scene in the Ford pickup they had come to seize, but they couldn’t be positive whether it was the actual vehicle.

They all decided the right move was to enter the property and see if the Ford pickup truck was still there.

The bailiffs used a bolt cutter to the cut the lock on the gate, and the five of them, wary of the dogs, advanced cautiously towards Roszko’s inner compound.

When the dogs approached angrily, Cpl. Martin and Cst. Schiemann used pepper spray to back them off. Eventually they turned tail and scurried into an old grain storage shed at the southwest corner of the Quonset. There was a fair-sized doghouse beside the shed and Julie Letal used her PC to push the doghouse in front of the door to the shed. This effectively blocked the shed door and ensured the dogs could not get out.

To determine that the Ford pickup wasn’t still on Roszko’s property, the bailiffs decided to take a look inside the Quonset. To their surprise, they found that the small entrance door to the building — the human door — wasn’t locked. There was a padlock hanging in the clasp of the human door but it wasn’t snapped shut.

So in they went: Perry first, followed by Hnatiw, then Letal, Martin, and Schiemann.

The first thing that hit them was the powerful, distinctive odour of marijuana, which, in its growing stage, gives a smell similar to a skunk’s discharge.

“Right off the bat,” says Cpl. Martin, “you could tell there was a grow operation inside the building.”

It was difficult to walk about in the Quonset. The dirt floor was cluttered with all kinds of automotive parts — axles, engine parts, dashboards, fenders, frames, and a number of tools. There were also two partially dismantled pickup trucks, a quad recreation vehicle, parts of several motorcycles, and a big Wermac generator on wheels.

Julie Letal recognized the Wermac generator as a stolen article from a photo that Cst. Cindie Dennis had shown her from one of her property files. The generator was valued at $30,000.

In the back (southwest) corner of the Quonset, there were two wooden-framed structures covered with black plastic sheeting. Above these structures was a platform that ran almost the width of the building.

Schiemann and Letal worked their way through the debris on the floor and peered into one of the plywood structures through an open flap in the plastic.

“There’s a grow op back here, Corporal,” Peter called to Jim Martin.

Jim Martin went to the back of the building and had a look through the flap in the plastic sheeting. Inside he saw hundreds of marijuana plants in various stages of growth.

“That’s for sure!” he responded. “That’s for sure.”

Because the marijuana plants and the dismantled vehicles obviously indicated the building was the scene of criminal activity, Cpl. Martin immediately ordered everyone out.

“C’mon everybody,” Martin shouted, “let’s get out of here. There’s no point in looking around any further. We need a search warrant.”

As everyone filed out of the building, Cpl. Jeff Whipple pulled his PC up beside the Quonset. Then Constables Clayton Seguin and Brock Myrol arrived in their cruiser.

Martin contacted the Whitecourt Detachment office and notified them of the situation at Roszko’s property, including the fact that Roszko had fled the scene in his white Ford pickup. He wanted all the detachments in the area to be on the lookout for him and arrest him on sight.

Throughout the afternoon, police cruisers patrolled the area near Roszko’s farm, looking for him. Later in the day, a man who lived north of Roszko alerted the police that he’d seen James Roszko driving on a road near his farm. A cruiser was dispatched to look for him but was unable to locate him.

Subsequently, a province-wide dispatch called a “BOLO” (an acronym for Be on the Lookout For) was issued to locate and arrest James Michael Roszko. The bulletin was sent to every serving RCMP member from Wetaskiwin, south of Edmonton, to the borders of British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories.

Meanwhile, back at Roszko’s farm, Jim Martin and Peter Schiemann prepared to leave the scene to return to the detachment office in order to prepare an application for a search warrant on Roszko’s property.

In their absence, Martin ordered Julie Letal and Cst. Trevor Josok, a member of the Whitecourt Detachment, to stay on the property and secure the scene. Josok had arrived while the others were going through the Quonset.

Martin and Schiemann got back to the detachment office by four-fifteen p.m. and began the meticulous process of completing the search warrant application. In doing so, they had to be very careful to accurately specify the evidence they sought to retrieve from Roszko’s Quonset hut and from his trailer.

When they were both satisfied that they had correctly met all the specifics for the search, Martin faxed the application to a Justice of the Peace in Edmonton.

While waiting for a reply, Martin and Schiemann started making phone calls to get resources lined up for the mammoth search operation that lay ahead. First of all, they needed an ample crew of members to search and secure the Quonset hut. This would require some assistance from the Whitecourt Detachment.

At 5:00 p.m., Martin put in a call to the Auto Theft Section at Edmonton Headquarters. Constable Steve Vigor, one of their specialists, took the call and listened as Martin outlined the situation at Roszko’s farm.

When Martin had finished his summary, Vigor asked, “Do you need ERT?”

He was referring to Edmonton Headquarters’ twelve-member Emergency Response Team, a specially trained and heavily armed assault unit that in some U.S. jurisdictions is called a SWAT team.

Martin replied, “No. The place is fully covered.”

“Okay, then.”

“When do you think you guys will be out here?”

“Well . . . considering the length of time it will take you to get the search warrant approved . . . and the limited lighting in the Quonset hut, I don’t think there’s much sense in us coming out right away.”

“I think you’re right.”

“Okay, then. We’ll be out first thing tomorrow morning,” Vigor advised.

That was fine with Martin.

Shortly after that, Cst. Schiemann returned to the Roszko property with Cst. Brock Myrol, a recent graduate of the RCMP Training Academy in Regina. When they arrived, Cst. Josok departed.

Around six-thirty p.m., the two bailiffs returned to Edmonton, but before they departed, they placed a “Notice of Seizure” between the outside and inside doors of Roszko’s mobile home.

By 7:55 p.m., the Edmonton Justice of the Peace had completed his review of the search warrant application and signed off on it, giving Martin authority to search and seize evidence from Roszko’s Quonset hut and from the trailer in which he lived.

Martin then assembled a search team that included Constables Peter Schiemann, Julie Letal, Brock Myrol, Al Starman, and Joe Sangster — all from the Mayerthorpe Detachment.

Wednesday, March 2, was Brock Myrol’s day off. However, when he heard about the marijuana operation and the chop shop activity that had been discovered on James Roszko’s farm, he was eager to go out there and assist with the investigation. And, as it turned out, Cpl. Martin needed help checking out the property and the buildings.

Brock and his fiancée, Anjila Steeves, who were both new to Mayerthorpe, lived in a rented house in the town. As he prepared to leave for Roszko’s place at 6:00 p.m., Anjila asked him, “Do you have your vest on?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“Do you have it on right?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Because I don’t want you to get shot.”

Brock smiled. Then he was out the door and on his way to the detachment office.

By the time the entire search team arrived at Roszko’s property, it was about eight-forty p.m. As soon as they got there, they began to scour the property for evidence and to record a list of the stolen items that would be used against Roszko in court.

One of the significant finds they located early in their search was a small stash of ammunition.

Around nine o’clock, Cst. Cindie Dennis of the Mayerthorpe Detachment brought out some pizza for the search crew. As she was rounding the corner onto Range Road 75, one of the pizza boxes slipped off the seat and dumped a pie face down on the floor of her vehicle. She pulled over and scooped up the topping and tried to put everything back in place.

“I did the best I could to make it look nice and normal.

“When I arrived at Roszko’s Quonset, everyone was really hungry and wanted to get at the pizza right away. They didn’t suspect anything was wrong, but I felt I had to tell them what had happened.”

When Brock Myrol heard about her little misadventure, he hesitated briefly but then he said, “Looks all right to me.” Then he grabbed a slice and dug in.

Cindie says, “They all must have been starving, because nobody gave it a second thought . . . they just started eating . . . and me, too.”

Cindie recalls they put the pizzas on the hood of one of the police cars and stood around eating by the light from the Quonset hut.

“That’s a lasting memory from that night . . . all of us huddled together eating pizza . . . nobody saying very much . . . just enjoying the pizza.”

After their little break, everyone went back to work. And Cindie joined the search crew.

It soon became evident that the marijuana grow operation was larger than Cpl. Martin had originally thought. Consequently, shortly after nine-thirty p.m., he phoned Cpl. Lorne Adamitz of the Edmonton RCMP “Green Team,” a specialized unit responsible for investigating large-scale drug operations, and advised him of the situation at Roszko’s farm. Adamitz agreed to put together a unit immediately and said they would be on their way out there as soon as possible.

Then Martin called Tom Eichhorn, the owner of Uptown Auto Services in Mayerthorpe, to make arrangements to have some of the stolen property in Roszko’s Quonset towed away and impounded as evidence.

Eichhorn, in turn, contacted two of his mechanics, Bruce Pearce and Kenny Poeter, and told them they were going to help the RCMP recover some stolen property. When Poeter found out their destination was Roszko’s place, he says he was “a little worried,” but he was curious, too. Pearce said the police gave them no indication that the assignment was any more dangerous than any other repossession, although Eichhorn did say that Roszko had fled the scene.

“I guess I felt safe, but I was nervous,” Pearce says. “Nobody knew where he was. He could have been anywhere. We just basically wanted to get loaded and get out.”

The mechanics describe the Quonset as having a cluttered, untidy interior with a sandy floor and unadorned walls.

As soon as they got there, they started removing some of the larger pieces of stolen goods. These included the Wermac generator, a 1997 motorcycle, two 1998 Honda motorcycles, a red 2003 GMC truck, a grey 2002 Ford F350 truck, a 1990 John Deere garden tractor, and a number of automotive parts.

As Martin and his crew kept searching and recording, Sgt. Brian Pinder, the NCO in command of the Mayerthorpe Detachment, arrived with coffee for everyone. Although Brian was on holiday leave, he had not gone away from the area. Upon learning of the situation at Roszko’s farm, he placed himself back on duty and came out to the farm to check things out for himself. Martin gave him a thorough briefing on the progress of the investigation.

Brock Myrol was assigned to guard Roszko’s trailer. When he looked inside he could see that the place was a mess. It was dirty and dishevelled and reeked of the smell of marijuana. During the search of the trailer, investigators found lists of all the RCMP members in the Mayerthorpe, Evansburg, and Whitecourt detachments, including their addresses and phone numbers plus the call sign and cell-phone numbers of their police cars.

They also found notes Roszko had made on every encounter he’d had with various police members.

Other items they discovered on the property included:

•Police scanners

•Wallets with various sets of identification, one containing $1,585 in cash

•Several sets of handcuffs and leg irons

•Seven long arms, i.e., rifles and shotguns

It was after midnight when Cpl. Adamitz and his “Green Team” arrived from the city. With him were RCMP Constables Al Gulash and Ray Savage, plus another member of the Edmonton City Green Team unit. It took them over two hours to dismantle the grow operation, and in the process they seized 280 marijuana plants, along with various items of grow paraphernalia. These included carefully recorded harvesting books and other documents pertaining to the science and care of growing marijuana.

By three a.m., the search was complete, except for the removal of the John Deere garden tractor, some automotive parts, chopped-up truck frames, and a truck shell that was outside the west end of the Quonset.

All of the police who searched Roszko’s property that day were well aware that he had been in trouble with the law before. More often than not he had managed to wriggle his way out of being convicted.

This time, he was in very serious trouble and none of them were surprised.