James Roszko (Mayerthorpe Freelancer)

2 | Roszko

JAMES ROSZKO WAS a violent, angry, emotionally unstable loner who had a widespread reputation for being an abusive bully and a sexual predator and pervert. He was also a man who hated the police and loved guns and knew how to use them.

These qualities of being violent, angry, unstable, a loner, and having a facility with a gun constitute the classic profile of a police killer.

RCMP files document case after case of instances where these types of men have murdered police officers.

In 1932, Albert Johnson, a reclusive trapper, who was a deadly shot with a rifle, was notorious for stealing gold from dead men’s teeth. As the so-called Mad Trapper of Rat River, Johnson murdered thirty-one-year-old Cst. Edgar Millen during a chase-and-pursuit gunfight in the Northwest Territories.

In 1962, George Booth, thirty-two, a “mentally unbalanced” loner who reportedly could shoot the eye out of an eagle at sixty yards, murdered three young Mounties in a prolonged gun battle at Kamloops, British Columbia.

In 1970, Wilfred Stanley Robertson, an odd little woodsman with a bad temper and deadeye aim, shot and killed two Mounties who had been called to a domestic dispute at his isolated shack in the Saskatchewan bush. He killed one Mountie at point-blank range. He shot the other, who was a long way off, through the glass pane of a window in his kitchen. As both men lay dying on his premises, Robertson sat down and finished eating his supper.

James Roszko (Mayerthorpe Freelancer)

In 1978, a distraught loner named Leslie Crombie, who lived in a mobile home in rural New Brunswick, was being interviewed by two Mounties regarding a custody dispute over his young daughter. In the middle of the interview, Crombie excused himself, went into his bedroom, got his rifle, and came out shooting. He killed both policemen before they had a chance to draw their guns.

Dog master Michael Buday was shot and killed in 1985 at Teslin Lake, British Columbia, by Michael Oros, a psychotic loner who was a trapper and hunter.

In 2004, Jim Galloway, another RCMP dog master, was murdered in Spruce Grove, Alberta, by Martin Ostopovich, a desperately unstable man who was in possession of a number of high-powered rifles. Although Ostopovich was living with his wife, he was alienated from almost everyone.

These are just a few examples of murderers who have killed police suddenly and without provocation. All of them were loners, emotionally unstable, angry, and good with guns.

This same combination of characteristics fit James Roszko to a tee.

Roszko was born in 1959, the youngest of Bill and Stephanie Roszko’s eight children. He was baptized as a Ukrainian Catholic at St. John the Baptist Parish near Rochfort Bridge and grew up attending church with his parents.

But when James was twelve years old, his mother left the family, and Bill, who is now deceased, had to raise the children on his own.

That seemed to be a pivotal point in his life. His father said, “James seemed to turn against religion then. That’s when I began to see warning signs in his behaviour.

“I used to tell Jim to get ready [for church], but he fired back at me that I didn’t need to preach to him because I was no preacher. I felt like I was between the devil and the deep blue sea. I used to pray that God would protect my youngest son, because when I tried to reach out to him, he pushed me away.”

James Roszko at his sister’s home in Whitecourt, Alberta. (CBC)

Their relationship really soured when James was sixteen and Bill found a stolen gun in his room. And it deteriorated even further when Bill discovered James was using marijuana.

James’s violent temper clearly came to the surface when, at seventeen, he learned that his mother had been badly beaten by an estranged male partner.

“Jimmy wanted to kill him,” Bill said. “He went and took his mother to the hospital. I think this pushed him over the edge.”

James’s sister Josephine Ruel felt sorry for her brother. She said he went through a lot. “It started very young. We tried to let him know we’d help him. But he couldn’t overcome it. I knew he was the one kid who needed more love than anyone else.”

But Jimmy Roszko was hard for people to love.

Although he was only five feet five inches tall and 150 pounds, even as a teenager he was a snarling, snapping, foul-mouthed ball of anger who seemed to enjoy confrontation. Anyone who crossed him received a curse-laden tongue-lashing. And as he grew older, he began to bully younger people and threaten them.

As Mayerthorpe’s number one problem child, he became a pariah in the community. Local people dubbed him a “ticking time bomb” and a “nut case.”

As James grew older and got in more and more trouble with the law, most of his brothers and sisters stayed away from him. Some wanted nothing to do with him.

His family, his friends, even his lawyer say he hated the RCMP and blamed them for everything wrong with his life.

Kim Connell, who is now retired from the RCMP, spent ten years of his police service posted at Mayerthorpe. He says, “Every time you met him, it was a violent confrontation. Even during routine traffic checks. A member would stop him and the argument would be on . . . the screaming and yelling and spitting.”

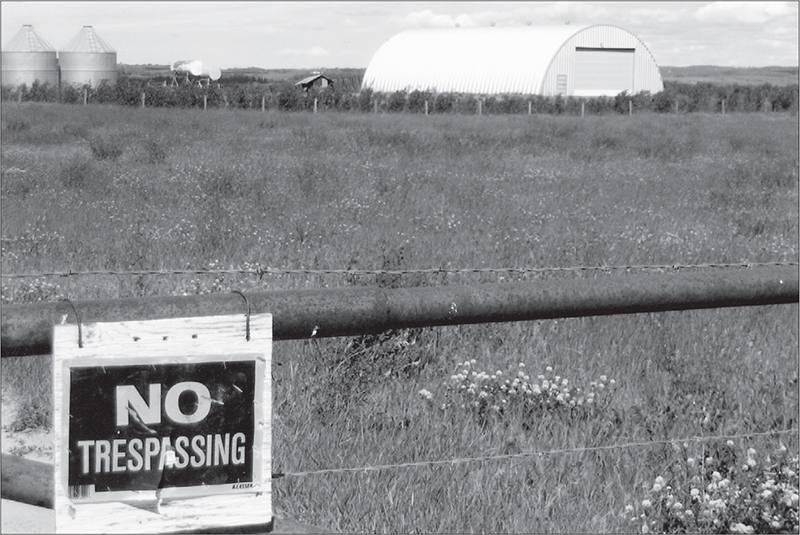

Roszko’s Quonset hut as seen from his gate on Range Road 75.

In 1999, Brenda Storm, a bailiff, put on her body armour when she was sent to seize cattle on Roszko’s farm. In her report she wrote: “Called a number of informants including the RCMP about this debtor. Learned he was quite dangerous . . . possibly in possession of a number of firearms. Has a long history of assaults . . . is known to have booby-trapped and used a spike belt to discourage vehicles.”

After Brenda met him, she wrote: “One of the worst psychopaths it has ever been my misfortune to run into. His hatred for police was evident. He blamed all of his problems on the RCMP.”

Roszko used to go into the local newspaper office of the Mayerthorpe Freelancer on a regular basis to complain about the police. He wrote letters to the editor complaining about the police’s harassing him. He claimed the police were following him and he wanted them to leave him alone. But the paper never published any of his paranoia.

They did print one of his letters where he complained about the local veterinarian’s being stopped for speeding when he was hurrying to save a dying calf.

But the woman who owned the sick calf sent in her own letter of reply saying that Roszko’s description of the situation was inaccurate. Furthermore, she didn’t need James Roszko speaking for her in the newspaper.

He would also try to put ads in the Freelancer saying terrible things about his enemies. Margaret Thibault, the newspaper’s editor, says, “I guess he figured if I buy an advertisement, I can put whatever I want in it.

“I told him we had standards we followed and we would not accept libellous ads.”

Margaret, like others in the community, found Roszko to be kind of a Jekyll and Hyde. He could be charming and reasonable for a while until he realized he wasn’t going to get his way. Then he could turn into a monster. When he got mad he would vibrate and shake with anger.

One time he got very angry with Lorraine Dwyer, the Freelancer receptionist, who refused to publish one of the Christmas ads he had composed. It read: “Don’t drink and drive, you might spill some.”

When Lorraine turned him down, he began shouting and banging the glass top on the office counter.

Margaret came out of her office and said, “Stop that!”

James demanded to know what was wrong with his ad. Margaret explained, “Our paper doesn’t condone drinking and driving. And we’re not going to print it.” Then she added, “And I don’t want you behaving like that in here.”

James seemed to cool down then and said, “I’m sorry. I’m just upset”

Although he’d stopped his ranting, Margaret says, “He still had that devil dancing in his eyes . . . like he was smouldering . . . ready to burst into flames.”

But Margaret knew the secret to handling James Roszko. People had to stand up to him and show him they weren’t afraid.

Margaret says, “There were grave concerns in the community about him hurting other people. He clearly had that capability. But that was a reputation he sought . . . and built up. He wanted to make people believe he was dangerous.

“I wasn’t afraid of him. Apparently there was a list of places the police told him to stay away from. And the Freelancer was one of those places. I didn’t think we needed to be on that list.”

And there was a slyness about James Roszko. Especially when he wanted to induce local young men to come out to his farm. First of all he would choose the ones he thought he could manipulate and then he would ingratiate himself with them.

Once he became familiar with the person, he would invite him to come out and work on his farm for pay. When they got out there, he would make sure they had a pleasure-filled week by feeding them alcohol and drugs. Then he would engage them in acts of homosexuality. He used the automatic timer on his camera to take pictures of them performing drunken sex acts.

After that, he had them under his control.

He would tell them, “If you don’t do what I want, I’ll show people the pictures and tell them what you were doing out here.”

Or he’d threaten them by showing them his guns and saying, “You talk to anyone and I’ll take care of you.”

It was all very clever. The only witnesses to what went on in his trailer were the ones participating in the action.

Seldom did anyone complain to the police, because most of these boys — and there were at least thirty of them over the years — were deathly afraid he would carry through on his threats.

The few who did lay charges would not show up in court to testify, because Roszko would contact them and threaten to kill them.

Margaret Thibault says, “That’s how it went time after time. We saw charges laid; then saw the charges dropped.”

On one occasion, Roszko dropped a boy off at the high school who was high as a kite on dope. The police happened to be right there and saw him stagger out of the car. They investigated and laid charges, but the young boy refused to take the stand as a witness against him.

James Roszko had become Mayerthorpe’s worst nightmare.

And everyone in town knew it. Andria Gogan, the paramedic supervisor with Associated Ambulance says, “They kept putting him in jail and then he’d get out.”

And it was common knowledge he kept guns at his farm. In spite of a court-imposed ban on Roszko’s possessing firearms, the young people he invited to his farm knew he kept several weapons on his property. He would show them off to the boys and practise shooting in front of them, sometimes on targets 200 metres away. And they all could see he was a crack shot.

Between 1993 and 1998, the RCMP went to Roszko’s farm three times with search warrants looking for illegal, unregistered weapons. They especially wanted to find the Heckler and Koch semi-automatic assault rifle that it was reported he had bought in the United States and smuggled into Canada twenty-five years before. But the Mounties were unsuccessful in their searches.

Retired RCMP Sergeant Cliff Wade says, “We didn’t find the one we were looking for.”

Another nagging concern for the police and the concerned citizens in the community was, how did Roszko support himself?

At one time, years ago, he had been employed. His most lucrative jobs were in the 1970s when he worked as a driller in the U.S. oilfields. After that, he ran a few head of cattle on his mother’s farm. But in the last few years he seemed to survive with few resources, living alone with no livestock on the property on Range Road 75.

Rumours circulated about his Quonset hut and what he kept in it, but there was never any proof that something illegal was transpiring there.

An anonymous Mayerthorpe resident who doesn’t want to be identified for fear that Roszko’s allies might target him says that he worked on Roszko’s property and knew him for twenty years. He believes that after Roszko was released from prison in August 2002 after serving time for sexual assault, he began working with a “small crew of career criminals” from the Mayerthorpe area.

Was it this group that was involved in the marijuana grow and the chop shop activity in his Quonset hut? Or was Roszko running this operation by himself?

With so many young men under his control, it’s certainly possible that he was operating like Fagan,1 sending the boys out to steal cars and trucks and anything else of value they could get their hands on.

Then again, Roszko was crafty enough to do a lot of illegal things on his own, without witnesses.

In one instance, he supposedly bought a new truck with very little money down but with high monthly payments. Roszko stripped the truck bare in his Quonset and sold the parts. Then he hid the demolished frame in the bush and made an insurance claim for his stolen truck.

As one Mayerthorpe resident remarked, “Oh, he had brains, all right. Except all his energy went in the wrong direction. He had extreme mental problems. He thought he was the centre of the world. And there was no connection between his head and his heart. He had no feelings for anyone except maybe his mother.”

The best insight into James Roszko’s troubled personality can be gleaned from his documented criminal history in the courts.

In total, Roszko was convicted on fourteen of the forty-four charges he faced during sixteen criminal prosecutions. Often several charges came from one particular set of circumstances. For instance, eighteen charges came from three prosecutions alone.

Many of the charges against him were either stayed or acquitted. That’s because there were instances when the prosecutors lacked the evidence to proceed, or uncooperative and/or unreliable witnesses compromised the prosecutions.

Roszko’s criminal history began on February 18, 1976, when he was seventeen years of age. That’s when he was charged with two counts of break and enter, for which he was fined $150 on each count and placed on one year of probation.

In November of that same year, he was charged with one count of theft under $200 and fined $250.

On January 24, 1978, he received a suspended sentence and a probation order of eighteen months for one count of possession of stolen property and one count of break and enter.

In April 1979, he was charged with one count of making harassing telephone calls plus three counts of breach of his probation. Roszko was convicted and sentenced to thirty days in jail for the phone calls plus fifteen days for breach of probation to be served consecutively.

In December 1990, as a result of an argument with a school trustee over changes of a school bus stop, Roszko was convicted on one count of uttering threats to cause death or serious bodily harm and fined $250. At this time he was thirty-one years of age.

In March 1993, he pled guilty to two traffic tickets: driving without his seat belt engaged and having tinted windows on his truck, for which he was fined $25 on each count. That same day he was charged with causing a disturbance by using obscene language with the RCMP officer who gave him the tickets.

On June 17, 1993, Roszko, in turn, initiated a civil suit against Her Majesty the Queen and this same RCMP officer for “abuse of public office, false imprisonment, detention, and malicious prosecution.” Roszko’s lawsuit was dismissed on May 16, 2000, because he did not take the required legal steps to pursue the civil action.

On September 28, 1993, he was charged with one count of assault that was stayed when witnesses were mistakenly issued subpoenas for the wrong court date. The clerical error was only discovered when witnesses did not attend the court as expected.

In September 1993, he was charged with one count of impersonating an officer when he identified himself as an RCMP officer while attempting to trace a phone call. Roszko was acquitted because an essential witness in the case failed to attend the proceedings.

On December 1, 1993, James was charged with eight counts for a series of crimes allegedly committed between May 24, 1993, and December 1, 1993. These charges were based on a complaint by “Bradley,” a pseudonym used to protect the identity of the complainant. The convoluted series of events pertaining to these charges is a good illustration of Roszko’s bizarre homosexual relationship with a local boy.

Bradley, who worked on Roszko’s farm, went on trip to the United States with him. They crossed the border illegally and drove to Utah, where Roszko purchased a Beretta 9mm handgun.

During the return trip to Canada, Roszko repeatedly asked to see Bradley’s penis. When Bradley refused, Roszko pulled out the Beretta, loaded it, cocked the gun, and pointed it at Bradley’s head. This assault continued for several miles until Roszko was pulled over for speeding. At that time, Bradley made no complaint to the highway policeman.

In early July 1993, Bradley claimed Roszko went to his home and pulled the gun on him again. At that time, Bradley testified that Roszko allegedly held him down on a bed and told him “he had a job to do,” which was interpreted by Bradley to mean that Roszko was going to kill him. Then a friend of Bradley’s came in and interrupted the assault. Bradley waited until his friend left then got a knife from the kitchen and stabbed Roszko in the jaw. Then Bradley took Roszko to the hospital

In October 1993, while Bradley was helping James put a replacement bumper on Roszko’s truck, he reported that James offered him $10,000 to kill Roszko’s enemy, a guy named “Conrad.” Roszko made this offer twice. For this murder, James suggested Bradley use Roszko’s rifle and he would supply Bradley with an alibi. Bradley refused these offers.

On December 1, 1993 during a chance meeting between the two men at Whitecourt, Roszko persisted in trying to speak to Bradley, who did not want to talk to him. However, after lengthy persuasion, Bradley agreed to come out to Roszko’s farm to inspect one of James’s vehicles. When Bradley arrived at the farm, Roszko told him he needed to drive out into the fields to check on his cattle. But he returned brandishing a shotgun and produced a set of handcuffs that he told Bradley to put on. When Roszko loaded the shotgun and began working the action it frightened Bradley and he complied with Roszko’s demands.

Then a conversation ensued where James made it clear he was angry with Bradley because he had been avoiding him for the past month. James wanted to know what Bradley had been telling people about their relationship. When Bradley denied saying anything to anybody, Roszko hit him in the face. After a long and heated argument, Roszko released Bradley from the cuffs so they could have a fair fight.

When the fight was over, Roszko took Bradley to his house and said he still didn’t trust him. James said he “needed something” to keep him from talking. So Roszko decided to use a camera timer and take pictures of the two of them engaged in a sex act, which he could use to prevent Bradley from talking. Bradley then performed oral sex on Roszko. However, Bradley was prepared to testify that he had agreed to the oral sex and the pornographic photos.

The trial commenced on June 3 in Queen’s Bench at Edmonton before a judge and jury. But, as the Crown had anticipated, Bradley did not attend court to testify.

One week before the trial, Bradley fled to British Columbia. The Crown had a witness warrant issued and Bradley was arrested and brought back to Edmonton. Bradley tried to convince the Crown that the information he had provided to the police was all a misunderstanding.

Bradley was released from the Edmonton Remand Centre and scheduled to testify the next day. But as expected, he fled the scene again. Consequently, a mistrial was declared and a warrant was issued for Bradley’s arrest.

While that case illustrates the frustration the Crown experienced in attempting to prosecute Roszko, the following matter demonstrates the serpentine procedures Roszko would follow to avoid paying a minor speeding ticket.

The trial for Roszko’s speeding ticket commenced on March 11, 1994. After requesting numerous adjournments, Roszko was forced to come to trial on November 24, 1994. Although he applied for yet another adjournment, he was denied. When he was convicted at trial, he appealed. A new trial was granted on the basis that the judge erred in not granting Roszko’s recent adjournment request.

The retrial for the speeding ticket took place on October 10, 1996, at which time James was found guilty. He appealed that verdict but was unsuccessful and had to pay the fine.

But he had kept the matter before the courts for nineteen months before this relatively minor issue was resolved.

In March 1994, he was charged with one count of breaching a condition of recognizance, for which he was acquitted, and two counts of obstructing justice, which were discharged.

Up to this date, by using one stratagem or another, Roszko had gotten off lightly for his crimes.

But on March 29, 1994, he was about to meet his Waterloo.

On that date, a trial commenced wherein he was charged with one count of sexual assault and one count of sexual touching.

Evidence presented during the trial revealed that from January 1983 until December 1989, Roszko had sexually assaulted “Edward” on multiple occasions. These assaults began when the victim was eleven years old and James Roszko was thirty.

The assaults included Roszko having Edward fondle James’s penis as well as Roszko masturbating the victim. These acts took place approximately once a week and progressed in intensity until Roszko began performing fellatio on the victim. On one occasion the accused attempted anal intercourse with the victim but failed because Edward resisted.

The victim did not report these sexual assaults to the police until March 26, 1994, when he was twenty-two years old.

The trial commenced on Sept. 28, 1995, and resulted in James being convicted and sentenced to five years in the penitentiary.

But Roszko successfully appealed that trial and a new trial began on April 12, 2000, where he was found guilty again, but received a lesser sentence of two and a half years in prison. He then appealed that conviction but his appeal was dismissed.

Although his nominal two-and-a-half-year sentence did not seem to fit his horrible crimes, at least Roszko’s sexual deviance had finally been exposed. And the community had the satisfaction of knowing he would be kept off the streets for a couple of years.

However, even during the years that these trials were taking place, Roszko continued to commit other crimes. On January 1, 1995, he was charged with assaulting Edward with pepper spray, possession of a prohibited weapon (the pepper spray), causing a disturbance, and one count of breach of recognizance. This all came about at a New Year’s Eve party while Roszko was out on appeal for his sexual assault charges. James went looking for Edward, found him in a bar, and sprayed him in the face.

This charge resulted in a stay of proceedings because Edward told the police he would not attend court and testify against the accused.

In April 1999, Roszko was charged for applying for a second social insurance number. He was acquitted on the grounds that the Crown did not prove James was the actual person who had signed the illicit application.

In September 1999, while Roszko was awaiting his second trial for the sex crimes, he was charged with aggravated assault on “Gregory,” plus assault with a weapon on Gregory, and assault with a weapon on “Harold,” and pointing a firearm at Gregory and Harold.

In this matter, these two boys had gone to Roszko’s farm to vandalize his property. Roszko was awakened by his dogs’ barking and by an alarm sounding on his Quonset hut. He grabbed a 12-gauge shotgun and went out and caught Harold near his barn. He tied Harold’s hands together and forced him to call out to Gregory to surrender.

After Gregory gave himself up, Roszko threatened them with his shotgun and made them walk towards his house. On the way, he fired a warning shot in the air to frighten them and make them obey his orders.

A second shot superficially hit Gregory on his face and his left arm. As a result of the injury, James offered to drive Gregory to the hospital. But when they all got into Roszko’s truck, it soon became evident that James wasn’t heading for the hospital. He was driving farther onto his own property.

Alarmed by this, the two boys overpowered James and took his shotgun away. Then they gave Roszko a beating, threw him out of his truck, retrieved their own vehicle, and drove to the hospital.

The results of the preliminary inquiry into this matter ordered Roszko to stand trial.

But he was not convicted, because when the trial convened on Oct. 16, 2003, the Crown case was compromised by the fact that both Gregory and Harold had lied during the preliminary inquiry by testifying that they had gone on Roszko’s property to steal gas. In truth they went there to vandalize his property and break some of his windows. Consequently, their entire testimony was tainted, and the Crown’s case against Roszko was acquitted.

The last charge registered against Roszko was dated December 29, 2004. It involved the two counts of mischief that Cpl. Jim Martin had charged against him for using a spike belt to damage the tires of the meter reader and the census taker who ventured onto his property. Roszko was scheduled to appear in court to face these charges on April 28, 2005.

Some people in the Mayerthorpe area thought Roszko’s long and varied criminal career should have qualified him to be classified as a dangerous offender. And in fact, at the time of his conviction for the sexual crimes, Alberta Justice flagged his file for consideration as a potential dangerous offender.

However, they concluded that proceeding with such an application against Roszko was not a possibility because his criminal history did not meet the Criminal Code of Canada criteria to support dangerous offender status.

While Roszko was in the penitentiary, a psychiatric profile stated that he refused to accept responsibility for his crimes and was preoccupied with legal proceedings. Furthermore, it revealed that he spurned all attempts at treatment. This made him serve two-thirds of his sentence rather than his being released earlier on parole. Even after his release, he was sent back for refusing to accept treatment and for failing to co-operate with his parole officer.

However, over and above Roszko’s lengthy record of criminal charges and his many court appearances, there are even more damaging rumours about his unlawful behaviour. In distinct and separate cases, three young men from the Whitecourt–Barrhead area who went to the police about James Roszko ended up dead. In each of these cases, the police had reason to suspect that Roszko might have been criminally involved.

The most suspicious of the three cases involved a mixed-blood, bespectacled, teenager named Dale Mindus who lived in Whitecourt. After visiting Roszko’s farm and working with him there, Dale had become an “acquaintance” of Jimmy Roszko’s. However, several months later, when Dale attempted to sever his relationship with Jimmy, Roszko became very angry and began to stalk the young man.

Although Mindus moved in with his sister Tracy and her husband, Cash MacMillan, in Whitecourt, Roszko kept pestering him and threatening the MacMillans at their house.

Macmillan, at six feet two inches and 220 pounds, is a big, handsome, strong man who is built like a pro football linebacker. Over the years, he developed and maintained his great body shape by working on physically demanding jobs in the nearby oil fields.

In an interview on CBC’s Fifth Estate, Cash MacMillan told the host, Linden MacIntyre: “He (Roszko) started appearing around our house, phoning the house. Somehow he had got our phone number. Dale was staying with us at the time.

“He started coming around quite often, just parking in front of the house and making it apparent . . . just letting us know he’s here . . . ‘I’m here’ . . . ‘I’m always here,’ or whatever. He was trying to intimidate, I guess.

“And the only one he really intimidated was Dale . . . and especially my wife. My wife was pregnant and he came . . . he started coming around more often when I wasn’t there. I was never there when he came.

“When Dale wasn’t there, he came a few times, and then when Dale went to work . . . we were all gone . . . then he really started coming around and it was just Tracy there. So I don’t know if he was looking for Dale or if he was watching Tracy. I’m not sure.”

Later in the interview, MacMillan told Linden MacIntyre: “Well, I started to worry about my family, because I thought when I’m there, there’s no problem. He’s not going to get past me. But when I’m away, I don’t know, I feared for my family. So that’s when I involved the RCMP, hoping they would take over and stop this.”

The Mounties responded. They came over and asked Cash to tell them precisely what Roszko was doing.

MacMillan told them Roszko was hanging around, parked either at the front of his house or in the back. The police told Cash that Roszko was parking on public property, and there was little they could do about it.

Cash told Linden MacIntyre: “So then . . . he showed up in my backyard . . . looking at my wife as she was washing the dishes. She looked out the window and he was right there.”

Linden MacIntyre: “In the yard?”

Cash: “Yes . . . looking up into the kitchen window. So as soon as they made eye contact, he left, and she phoned me and she phoned the police. They would do nothing. They would have nothing to do with it.”

Finally, in February 1998, Tracy called Cash in his shop at work and told him that Roszko was at the house again. It was around eleven-thirty a.m. She said she was vacuuming and looked out the window and he was out there. She said he was “freaking her out.”

Cash left the shop immediately and headed home with Dale in Dale’s truck. When they arrived at the house, Roszko spotted them and took off in his truck.

This time, Cash was determined to put an end to Roszko’s nonsense. He’d had enough of his pestering his wife and Dale, so he chased after him — at a very high rate of speed.

As they roared through town, Roszko turned into an alley that runs behind some of the downtown restaurants. Cash stayed right with him and finally pushed his truck to the side and made him skid to a stop in front of a telephone pole.

Then Cash ran over, pulled Roszko out of his truck, and dealt with him — as Linden Macintyre says — in “the old-fashioned way.” Cash pounded him into the ground.

Predictably, Jimmy Roszko went to the police and laid assault charges against MacMillan. Cash welcomed the charges because he felt that Roszko had been harassing his wife and his brother-in-law far too long. Furthermore, Cash believed he had been provoked into dealing with Roszko physically. And Dale Mindus, who was there and saw the physical confrontation, would testify as a witness against Roszko.

It appeared that all the parties involved looked forward to the case’s going to court.

But prior to the trial, Dale Mindus received a phone call from Jimmy Roszko. Roszko asked him, “What are you going to say in court?”

“The truth. I’m going to tell the truth.”

“You’ll never live that long,” Roszko replied and hung up.

Days later, Dale Mindus was found dead at the bottom of a stairwell in a basement apartment in Whitecourt. He had alcohol in his blood and died from a severe wound on his head. The cause of death was attributed to his falling down the stairs head first and smashing his head against a brick wall at the bottom of the staircase.

The case looked suspicious to the Crown and the police but no charges were laid against anyone in the case. The authorities conceded that Jimmy Roszko had both the motive and the means to commit such a crime, but, without proof, they could do nothing.

Linden MacIntyre, his producer, Scott Anderson, and a CBC crew went to the death scene and filmed it.

Linden says, “It looked very suspicious to me. There were only six stairs, they were carpeted, and there was no brick wall at the bottom of them. And there was very little blood spatter at the scene.

“The boy’s injuries were not consistent with the recorded explanation of his death which indicated that his head was bashed in. I think Dale Mindus was battered with a blunt object at some other place, dragged to that apartment, and dumped at the bottom of those stairs.”

But the authorities maintain that there is absolutely no proof of this.

To this day, Cash MacMillan, his wife, Tracy, and many other residents of the area are convinced that James Roszko had something to do with the murder of Dale Mindus.

Whether or not this is true, the Mindus case in 1998, above all others, makes it patently clear that James Roszko’s capacity for violence, paranoia, and hatred of authority was immense.

By all accounts, he truly was a disaster waiting to happen.