The travail of the Spanish people was unforgettably recorded in the Disasters of War , engravings which comment on the war of 1808-14, the famine of 1811-12 and the clerical reaction of the Restoration. When Goya finished the series, probably around 1820, he gave a set to his friend Cean Bermudez, in a finely bound volume. That volume bore, in gold, the title Capricho}

As he was finishing these plates, he was also working on his celebrated Disparates engravings, left unfinished when he went into hiding and exile after the overthrow of the regime established by the Revolution of 1820. These baffling and often startling ‘proverbs’ re-work in dark and fantastic manner many of the themes of the original Caprichos , and of the drawings which fill his private life after 1800. On his recovery from a desperate illness late in 1819 (recorded in a striking portrait of himself near death in the arms of his doctor) he set to work to cover the walls of his newly acquired and isolated house, Quinta del Sordo (House of the Deaf Man), with the unnerving Black Paintings. All these works, running through the Restoration into the Revolution of 1820 and punctuated (as in his personal crisis of 1792-3) by severe illness, bear a strong family resemblance to each other.

None of them were published in his lifetime. They represent a kind of climax to the long and rich series of private drawings, with their parallel uncommissioned paintings, in which Goya found full self-expression. In the engravings he surfaced, for after 1800 the real Goya goes underground, into his caprichos.

This dichotomy, implicit in the Caprichos of 1799, became explicit after 1800. Power at court was shared between the reactionary Caballero and the reformer Urquijo. The patronage of the latter secured Goya’s appointment, in October 1799, as First Court Painter, with a salary of 50,000 reales.

There were still to be moments of financial anxiety. Goya

received no salary under Joseph Bonaparte; at the end of his life, alienated and in exile, the painter took infinite pains to make sure of his pension from Ferdinand VII.

But, in effect, 1799 witnessed his achievement of financial independence. In 1803 he bought a second and spacious house which he gave to his son; inventories made at the death of his wife in 1812 register him as a solid bourgeois, comfortably placed, with a heavy investment in jewellery. 2 Some of the engravings he made during the terrible Madrid famine of 1811-12, with their acute awareness of the literally lethal consequences of class differentiation, seem to reflect a certain self-consciousness. From 1799, within limits, he could choose.

By 1801 he had made his choice; royal and commissioned work dwindles, the drive of his enterprise is into the private and the graphic. Throughout 1800, he was busy about the royal family. The preliminary studies for his appallingly candid Family of Charles IV, with its echoes of Velazquez, earned the complaisant commendation of that disconcerting clan.

He was fairly close to Godoy, whom Moratin counted a friend, and who, safely ensconced in exile later in life, preened himself on his ‘enlightenment’. Goya painted the ‘sausage- maker’ Prince of the Peace as a war hero; ran off several commissions for his public persona and the celebrated Majas, clothed and unclothed, for his private parts.

But in 1801, rather abruptly, his living connection with the Court broke. The family of Charles IV may have liked their portrait, but Goya painted no more for them. His services to the successor, Ferdinand VII, were formal, official, rather perfunctory and distinctly remote, as indeed they were to be to the intruding French king Joseph and the intruding English liberator, the Duke of Wellington. From this moment to the end of his life Goya’s official duties, unless susceptible to free interpretation, seem to have been a formal chore. 3

The moment for withdrawal was probably chosen for him.

At the end of 1800 the ultramontane offensive against the ‘Jansenists’ carried the court, which turned savagely on the ilustrados. Urquijo was dismissed and jailed. Jovellanos was plucked from Asturias and flung into prison in Majorca, where he was to remain until 1808. Reaction triumphed, save for one brief moment before the cataclysm when Godoy, trying to wriggle free from the grip of Napoleon, flirted with ‘liberalism’ again. With his patrons in jail, the author of the Caprichos needed to tread delicately. In 1802 the Duchess of Alba died in suspicious circumstances and her characteristically

eccentric testament was challenged; possibly another argument for caution. It was in 1803 that Goya, to protect himself from the clericals and at Godoy’s prompting, made over the plates of the Caprichos to the royal Calcograha in return for a pension to his son.

He withdrew, but not into silence. His portraiture, now that he could pick and choose, becomes an often breath-taking study of character. And his canvases are suddenly invaded by the middle class and even the pueblo. In 1805 his son married into the potent family of Giocoechea, a thrusting clan of merchants. Juan Martin Goicoechea, merchant of Saragossa, Goya’s earliest patron, was virtually the epitome of that species which Spain so signally lacked —the enlightened, improving bourgeois. Javier Goya married the daughter of

50. The water-seller, c. 1808-12

Martin Miguel Goicoechea, and his wife Juana Galarza, from another dynasty of Saragossa merchants. At the wedding Goya met Leocadia Zorrilla, who was to marry a German merchant but was to comfort the painter’s later years. Leocadia became notorious as a fierce and outspoken enemy of absolutism; her son was to serve in the radical militia after the Revolution of 1820. Martin Miguel Goicoechea ultimately went into exile as an afrancesado ; Goya was buried beside him in Bordeaux.

In 1805 Goya’s son married into what would have been an elite of the Spanish Revolution, had it ever happened. 4

And the good bourgeois of Madrid come under his brush, in the drawings, paintings and miniatures of the Goicoechea

51. The knife-grinder, c. 1808-12

and Galarza families, in a strong series of portraits, The Bookseller’s Wife and her kin. He turns to elaborate themes first sketched out in the Caprichos and the cabinet paintings of 1973-4; vivid, realist and genre paintings, the spotlit violence and drama of his bandit and cannibal sketches.

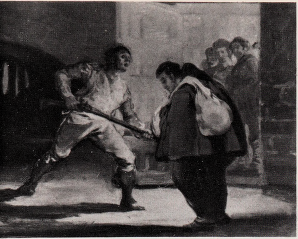

In the Water-Carrier and the Knife-Grinder, painted sometime in these years before 1812, to be followed by the magnificent Forge, the worker takes his place as a person in art, in superb and monumental achievement [50,51,52]. In 1806-7 there were the six small panels, almost a strip cartoon, recording the popular story of Friar Pedro’s capture of the bandit Adaragato in a style the world was to learn only from the

52. The forge, c. 1812-16

Disasters of War sixty years later [53]. In these compulsive works we enter a universe remote from the picturesque and paternalist ‘populism’ of the tapestry cartoons.

He turns above all, as in 1796, to his drawings. The first of the new albums began where the Madrid album stopped, using the same paper. It proved inadequate, so he started another, ruling black borders to make the drawings little paintings, carefully weaving the essential captions into the final product. On and on they run, from this point to the end of his life, marvellously executed and often brilliant drawings, in which he commented ceaselessly on life and found himself; Goya’s permanent capricho. The world of the official and the commissioned painting he still inhabited and frequently graced with talent. But it was in his drawings that the essential Goya, the Goya of the Caprichos tension, realized himself. Out of those drawings grew his great paintings and engravings.

From this point on, Goya public and Goya private co-exist in a species of schizophrenia.

No less schizophrenic was the reaction of his friends, the ilustrados , when Napoleon in 1808 overthrew the Bourbons, set up his brother as king and ordered the ‘enlightened’ regeneration of Spain, to be confronted by an enraged Spanish populace ferociously at war for their Church and King. Through the fall of the ancien regime, the public Goya moved goat-foot and hooded-eyed like the instinctive politique he was; in his personal drawings the private Goya moved through war and restoration to the Disasters and the Black Paintings.

Goya public found an almost comic exemplar in his notorious Allegory of the City of Madrid [49]. In December 1809 the city council ordered a portrait of ‘our present sovereign’ - Joseph Bonaparte - and by February 1810 Goya had duly painted the king’s head (from an engraving) into the medallion which is the focal point of the painting. In 1812 the French withdrew and Joseph was displaced by Constitution, in honour of the democratic constitution of the radical patriots of Cadiz. Within months the intruder King was back. Out went the Constitution and in went his face, only to be obliterated yet again in 1813 when the Constitution returned to its rightful place. In the following year, Ferdinand returned from France and abolished the Sacred Text at a stroke, to much popular acclamation. Goya had to dig out his six-year- old sketches of The Desired One. In 1823 after the revolution of 1820 had been crushed, Vicente Lopez made a better portrait of the Bourbon, but twenty years later, during one

53. The capture of the bandit El Maragato by Friar Pedro de Zaldivia, 1806-7

of Spain’s now customary civil wars, out it went again, to be replaced by El libro de la constitution. Finally after a futile attempt to recover Goya’s original portrait of Joseph Bonaparte, the Madrilenos, no doubt by this time desperate for a measure of patriotic permanence, settled on the Dos de Mayo. 5

The Dos de Mayo, which became Spain’s National Day, celebrated the rising of the plebeians of Madrid on 2 May 1808 against the French garrison. French troops had entered Spain for a campaign against Portugal. They were greeted with joy since it was widely assumed that they had come to overthrow Godoy. By this time dislike, indeed hatred, of the favourite had become universal: displaced aristocrats, frustrated reforming bureaucrats in the Charles III tradition, newer radical patriots hungering for a representative constitution, militant clericals angered by the increasing fiscal pressure on the Church, ilustrados and other respectable citizens despairing of their country, a conservative peasantry and a traditionalist urban artisanry ravaged by an economic crisis precipitated by war, inflation, the English destruction of the colonial trade, state bankruptcy and possibly the working-out of Caroline reform —all found a scapegoat in the ‘sausage-maker’ and the system of patronage he had created.

Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias, focused the discontent, and in 1807 the rivalry between him and Godoy broke into open conflict. Godoy’s last desperate intrigues to escape from Napoleon’s power were betrayed to the Emperor, and his attempt to remove Charles IV to Seville out of French control precipitated the Tumult of Aranjuez on 17 March 1808 when, at Ferdinand’s prompting, a military coup supported by the Madrid plebs terrorized Charles IV into dismissing Godoy and, two days later, into his own abdication. Ironically Ferdinand VII and his father became the first official afrancesados , for both appealed to Napoleon.

The Emperor had lost patience with Spain. In April both were summoned to Bayonne and both were deposed.

Ferdinand VII, The Desired One, passed to a comfortable and sycophantic exile as Joseph Bonaparte took the throne and proclaimed the regeneration of Spain in a constitution and a political regime which, no less ironically, embodied most of the measures for which the enlightened had long yearned-a modernized administration, the Code Napoleon, civil liberties, reconstructed and ‘rational’ provinces, the abolition of the Inquisition and aristocratic privilege, and the secularization of monasteries. ‘I appeal to you to save our

country’, wrote the ilustrado Azanza to the like-minded Jovellanos, ‘from the horrors which threaten it if you support the mad idea of resisting the orders of the Emperor of the French, which, in my opinion, are directed to the welfare of Spain.’ In vain: Jovellanos, released from prison, was to serve on the Central Junta which tried to organize the popular resistance. 6

It was the ‘lower classes’ of Madrid, protesting against the removal of the royal family on 2 May, who gave the signal for insurrection. At the height of the struggle in Madrid, members of the governing Junta, in full regalia, rode around the city, trying to restore order. They cooperated with the French general Murat in the pacification. Government refused to acknowledge Ferdinand’s abdication without consulting ‘the nation’ but it refused to recognize ‘the nation’ in the c low people’ of Madrid. Ferdinand’s last word had been an instruction to obey French orders. Joseph’s first ministry and household were staffed by familiar figures; his constitution was signed in July by ninety-one Spaniards of the highest distinction. At this critical moment official, establishment Spain stammered.

The rising was a rising of ‘the people’ with students and clergy active in the leadership. The French saw the entire movement as one of the ‘black’ canaille led by bigoted fanatics. This is far too simple. As in all traditionalist Church-and- King popular movements, the rising was ambivalent.

In a similar anti-French revolt in Naples the popular rebels defined a Jacobin as ‘a man in a carriage’ and in some parts of Spain the rising of 1808 took on the character of a jacquerie , had the makings of a Spanish 1789. The Godoy establishment was attacked, and if traditional authorities hesitated to join the struggle, they were attacked too.

The Captain General of Castile decided to join the war only after his colleague in Badajoz had been killed and students had erected a gallows in his courtyard. When the ragged popular army of Valencia came storming into Madrid with holy relics in their caps, the respectable classes were frightened out of their wits.

The national revolt began in mountainous Asturias in the north, where crowds of peasants and students forced authority to declare war on the French. 7 Traditional notables quickly took control of the movement and canalized its revolutionary potential, but Goya’s friend Melendez Valdes was saved from death at the hands of a crowd only by the intervention of priests with the exposed Host. Similarly a revolt in Galicia

led by a saddler threatened to get out of hand until ‘untainted’ notables took control. Generally speaking, the risings in the north rapidly took on a ‘unanimous’ character, but later conflict between the revolutionary juntas, the older authorities and the militant people in some places killed patriotic zeal. In Bilbao a popular and patriotic rising was bloodily suppressed by Spanish authority. As the rising moved south, generally triggered by an official refusal to commemorate St Ferdinand’s day, social conflict became more severe, particularly in the richer and more populous maritime provinces, Seville, the Andalusian cities, Valencia, Catalonia. Valencia was the authentic French nightmare: massacres by crowds led by Franciscans and Jesuits, artisans sitting beside nobles in the Juntas. In Cadiz only the Capuchins could control the people. But this ‘black’ populism masked a real threat to traditional order. There was a vague but widespread yearning for a patriotic ‘regeneration’, an unformed radicalism, behind the violent Catholicism and the cult of Ferdinand.

In Catalonia the popular militia waged a social as well as a national war and officers sent in to control them played the role of revolutionary and Caesarist tribunes.

Replies to the revolutionary authorities in 1809 reveal a widespread desire for ‘a constitution’ and an end to privilege. The revolutionary movement splintered in conflict between juntas. Central Junta, generals and popular militants. General Romana suppressed the juntas in Asturias and Galicia, and all the fight went out of them. Andalusia and Valencia were convulsed by faction. Seville nearly went to war with Granada. When the French swept through the area in 1810 they were greeted as liberators. The intelligentsia of Seville went over to the afrancesados en bloc; guerrilla activity was restricted to bandit areas like Ronda and a proletarian- smuggler fringe of the latifundia. The conflict in Valencia was diverted; the city remained quiet under the French, the only successful guerrilla was led by a monk, and popular action revived only to support the restored Ferdinand VII against the liberals.

» *■

The radical capture of the Cortes in Cadiz and the proclamation of the democratic Constitution of 1812 added a further contradiction. To many peasant communities and many client urban proletariats, liberalism meant economic death, and its natural enemy was a militant, conservative and political Catholicism. Nationalism, to a degree created in the struggle and focused on the guerrilla tradition, opposed a Catholic and conservative Spain to the ‘atheist’ and ‘liberal’

French and afrancesados, to whom patriot radicals were rapidly assimilated. On the other hand, the new nationalism focused on the guerrilla precisely because official, traditional Spain had collapsed so ignominiously. The guerrilla experience itself, particularly during the harsh years of famine, terror and counter-terror, tended to cut guerrilleros from their roots, in a sense to ‘professionalize’ them; there was a visible process of radicalization. Major legacies of the war were the ‘Caesarist liberalism’ of officers bred in the guerrilla tradition, the spread of Freemasonry, the beginnings of radicalization among the urban plebs and some rural provinces of high social tension. In 1808 the pueblo in arms turned instinctively from discredited authority to the friars and monks, but an underground tradition of radicalism generated during the war survived the Restoration to explode into sans-culotte militias and clubs after 1820. The guerrilla tradition was shared by extremists of left and right. Many a guerrilla leader was like El Pastor of the Basque lands, a militant, bloodthirsty and ‘black’ cleric; but many were not. The crowds might follow the Capuchins in 1808; within a generation some of them were burning churches. It is precisely the contradiction, the dichotomy, the dialectic which Goya caught in his twin engravings of the burro-pueblo in the ilustrado Caprichos [8,9].

The guerrilla, of course, was a response to the collapse of official Spain. In 1808, Spain, the land of the patria chica, shivered into fragments, juntas acted like sovereign powers. The mayor of the village of Mostoles formally declared war on Napoleon Bonaparte. The national resistance was a chaos of juntas, generals, militias. It was saved by the defensive heroism of the people, immortalized in the siege of Goya’s Saragossa under Palafox, where the citizens fought to the death and women like Agustina of Aragon manned guns amid a heap of corpses. The lucky victory of Baden forced a French withdrawal behind the Ebro. The Central Junta, joined by Floridablanca and Jovellanos, could not resolve the conflict between traditionalists and the preachers of national sovereignty, could not control the generals, could not surmount tradition or circumstance. The generalship of the Spanish army was inept to the point of lunacy. In 1809 the French came back and the Spanish army was shattered. In 1810 the French swept the south, and independent Spain shrank to the city of Cadiz, where a conservative Regency, caught between the French, the traditional Councils and the urban democracy of a mercantile city and its Americans, called a Cortes to mobilize a nation largely under French control.

The struggle fell to the guerrilla. At first whole communities took arms against the French-‘They have behaved worse than a horde of Hottentots. They have profaned our temples, insulted our religion and raped our women.’ Bloody lessons taught them to act in partisan bands. In the early days men (and women) simply sought to recreate an army; the debris of the official armies was constantly forming and reforming. They learned the lessons of guerrilla war the hard way.

The guerrilla was shaped not only by the exigencies of conflict but by topography and social formation. Navarre was one classic foco : a stable peasant community built around the ten-acre family holding, mountain communities, the only serious tension that between country and town. The guerrilla here was almost a function of community, staffed by younger sons, with women and priests acting as couriers. The Minas, ‘kings of Navarre’, enjoyed total security in their home province; when they ventured into Aragon, they were betrayed. In the end Espoz-y-Mina could lead out a small army of 8,000 men against the French.

Elsewhere, apart from a few officers and clerics, guerrilla leaders tended to emerge from those sub-cultures already in conflict with authority. Along the French road to Burgos through mountainous and wooded country, with its rich booty, smugglers took the lead, reinforced by the odd officer, monk, artisan. There was a similar smuggler concentration to the north-west of the central Meseta near Portugal. Ronda was a bandit and smuggler community in arms, and elsewhere in Andalusia bandits changed sides with a bewildering rapidity. On the central plateau, classic fish-in-water guerrillas materialized, peasants by day melting into small bands of partisans by night. The leaders tended to be drawn from local worthies-village doctors were active around Toledo and Cuenca —or from the mobile, semi-independent fringes of peasant society-horse-dealers, charcoal burners.

El Empecinado himself, most famous of the guerrillas, a brilliant technician of irregular warfare, was among other things a charcoal burner, a trade with a tough reputation.

The struggle developed in its own remorseless logic.

By 1811 the bands, which may have numbered 30,000 in all, were harassing the French into madness, serving as indispensable auxiliary to the field army of the Duke of Wellington. Counter-action was swift and merciless. Wholesale reprisal decimated local populations. During 1811, as Cadiz tried to send out officers to control and direct guerrilla operations and showered commissions on bandit chiefs, the

French developed serious and effective counter-insurgency tactics. Aragon was quartered with forts and protected roads; an urban militia was organized to beat off raids, as famine stalked the land and gripped Madrid itself. El Empecinado’s right hand man El Maneo (the one-armed) was bought off to form an anti-guerrilla guerrilla, the contra-Empecinado.

The process was repeated elsewhere and achieved a measure of success. With guerrillas and the local population competing for scarce supplies, with the peasantry caught in the terrible vice of guerrilla terror and French counter-terror, the survival of the guerrillas depended on a very fine balance of emotions. Numbers of the bands managed to survive, to embody the new myth of Spanish nationalism, to grow into small armies as Wellington’s troops finally turned the tide, and to express in themselves the basic contradiction of the national struggle, the dialectic between a black populism and a social radicalization.

The contradiction reached breaking point in Cadiz. In this miniscule free Spain, the radicals, supported by the self- interested action of the deputies from that America which was now breaking away into independence, won control of the Cortes and forced through the democratic Constitution of 1812 which, while acknowledging the special position of the Church, in effect rehearsed the regenerative constitution of Joseph Bonaparte. Clericals and traditionalists, alarmed at the developing threat to Church power and property from legislation in the spirit of Jovellanos’s Informe, organized resistance. Liberales (it was now that the word assumed its current meaning) confronted serviles, and when the French were driven from Spain in 1813 the struggle intensified.

When the French left, no fewer than 12,000 Spanish families left with them, drawn largely from the elite, the first of those exoduses of the intellectuals which were to characterize modern Spanish history. The motives of these afrancesados were mixed. In essence they shared the ideology of the patriot liberales, but there was perhaps a difference in temper. The afrancesados were more directly in the tradition of the bureaucratic enlightenment of Charles III; the liber ales’ commitment to popular sovereignty was alien to them.

In Joseph’s regime they saw the opportunity to carry reform through to its natural climax. Before the Russian campaign, in any event, who could hope to resist Napoleon? Their efforts, like those of Joseph, were sincere; it was the devastating character of the war, the rule of generals, the guerrillas, terror, counter-terror, massacre, rape, famine which rendered

nugatory all their reforms. The tragedy of the afrancesados symbolizes the political schizophrenia which destroyed the Spanish enlightened. In 1814 the Spain of Ferdinand VII spewed them out.

For with the return of The Desired One in 1814 the serviles triumphed. In May Ferdinand annulled the Constitution and, with massive popular support, launched a witch-hunt against afrancesados and patriot liberals alike. Crowds baying through Madrid smashed the stone of the Constitution. Their alleged motto ‘Long live our chains!’ may be a myth, but to dismayed liberals it expressed their spirit. Liberals were hunted down, jailed, killed, driven into exile. The Inquisition was restored, the Jesuits returned. A stifling conformism settled over public life. Many of the serviles had hoped for a ‘constitution’ of some more traditional kind than that of 1812; Ferdinand seemed bent on ministerial depotism and the undoing not merely of the work of Josephine Madrid and Constitutional Cadiz but of that of Charles III as well; ‘reform’ had opened the gates to ‘atheism’.

In fact Ferdinand himself was no fanatic, though his populist camarilla of advisers, through which he kept in touch with the Madrid plebs and underworld, often were. He was a survivor. Survival however proved difficult. The struggle to retain the American empire was failing, the country was bankrupt, ministers followed each other with bewildering rapidity. Survival demanded modernization, but modernization meant the afrancesados and the liberals; and how could they breathe in a society whose official ideology was the ferocious clerical reaction of the apostolicos and the Society of the Exterminating Angel ? Ferdinand was trapped, lurching from one expedient to the next as disaffected officers who found no place in the shrunken post-war army plunged into Masonic conspiracies and launched repeated pronunciamentos against the regime.

In 1819 a conspiracy against the regime by the respectable failed, but on New Year’s Day 1820 Major Riego led a mutiny in an army about to be shipped to the American War, and proclaimed the Constitution of 1812. After an agonizing pause, with revolts in a few cities, army officers refused to move against him, and Ferdinand’s autocracy collapsed. Amid widespread rejoicing, the king swore to the Constitution. Tragala , perro (‘swallow it, dog’, compare Goya’s Capricho No. 58 [19]) sang the crowds in the streets. The Hymn of Riego was to become the anthem of liberalism and the Spanish Republic.

What happened pre-figured the pattern of most revolutions

in nineteenth-century Spain. With the Constitution, there was an immediate lurch into liberalism, modernization, Europeanization in a society which lacked the social structure which could sustain and develop a bourgeois polity. The first leadership was moderate, anxious to revise the Constitution in a conservative direction but driven by its own logic and necessity to press home the attack on clerical property and privilege. The Church and the militant apostolicos at once moved into intransigent opposition, rallying the support of threatened and conservative peasant communities. At the same time the novel and militant radicalism of the urban democracy, intensifying with every shuffle towards liberalism and a capitalist economy, bubbled with impatience. The radical populism of the exaltados mushroomed in the urban militia, political clubs and journals, a virulent anti-clericalism.

Caught between these polarities, wrestling with the hostile and cunning king, holding aloof from the ‘traitor’ afrancesados who repaid them with a withering and demoralizing fire of criticism, moderate liberals stumbled into conservatism and were confronted by an insurrectionary explosion of the exaltados ; weathering a royalist coup, they lost power in 1822 to an exaltado ministry. At once the apostolicos and their peasantry took to the hills, in the guerrilla of the royalist Volunteers. The exaltados countered with a Jacobin terror.

The European powers, alarmed at the revolutionary example of the Spanish Constitution, which had become a palladium to Latin liberals, authorized France to intervene. The Hundred Thousand Sons of St Louis marched to restore legitimacy; the Spanish army was paralyzed and the constitutional regime collapsed.

The restoration of 1823-4 witnessed a bloody and ferocious White Terror, a murderous hunt after liberals and exaltados alike. There was another wave of refugees. The repression was savage but short. Ferdinand, with America now hopelessly lost and the country trapped in bankruptcy, shifted away from the partisan fury of the apostolicos , who turned instead to his brother Don Carlos. The king in the last years of his reign groped after a measure of consensus, took up again the measured ‘enlightenment’ of the Caroline tradition, appointed modernizers to ministries, opened the Prado, put out feelers to the afrancesados. In a final complex spasm of intrigue and conflict he tried to secure the succession for his daughter and to keep out Don Carlos; the court opened to the liberals and afrancesados , exiles returned, the exaltados stirred into life, their enemies put on their canvas shoes and picked up their

rifles. Spain braced itself for another lurch towards the liberal and bourgeois society, another Riego cycle. In 1833, on Ferdinand’s death, liberals came to power, Carlists rose in arms, the first churches burned. 8

What this generation experienced was the political disintegration of the Hispanic world and a crisis of Spanish identity. The ‘Two Spains’, which so haunt Spaniards writing their history, emerge from the fragmentation of the Caroline enlightenment in the crisis of the French Revolution.

When the First Carlist War broke out, Goya had been dead for five years. He finally broke with Spain during the White Terror of 1823-4 and joined the afrancesados in exile. The ‘Two Spains’, yoked together not least within his own mind, are prefigured in his Caprichos of 1799. They find reflection in the dualism of the public and private Goya which persisted through the crisis. 9

After the Tumult of Aranjuez, the First Court Painter was commissioned to paint Ferdinand VII. The king sat for him briefly twice before leaving for Bayonne; he never sat for Goya again. The 1808 sketches had to serve for all future portraits. Goya was in Madrid during the street fighting of 2-3 May. After the first French withdrawal he worked to complete an equestrian portrait of Ferdinand VII but was summoned by Palafox to record the heroic defence of Saragossa. Goya journeyed through war-torn Spain in the autumn of 1808, and this may well be the source of some of his earlier Disasters engravings and the paintings of guerrilla war scenes he made later [54]. When he returned to a Madrid re-occupied by the French, however, he took the oath to that Joseph Bonaparte who had abolished the Inquisition and closed two thirds of the convents.

During 1808—10 Goya painted a French general and many of the leading afrancesados. Among the latter were most of his friends. Moratin himself took office under Joseph, so did Melendez Valdes, Urquijo, Bernardo de Iriarte and a host of others. He painted the Goicoechea family, who were afrancesados to a man; one of them wears Joseph’s Royal Order - the ‘aubergine’. He painted the celebrated Minister of the Interior, Jose Manuel Romero, and Llorente, the former secretary of the Inquisition who wrote a scathing liberal indictment of it; the Llorente painting is one of the most alive. In 1810 he executed the Allegory of the City of Madrid; he helped to choose the paintings removed to France. In 1811 Goya was awarded the Josephine Royal Order himself.

He behaved, in short, like a complete afrancesado.

54. Making shot in the Sierra de Tardienta, c. 1810-14

Evidence presented on his behalf after the restoration of Ferdinand VII stressed that he had held himself aloof from the Intruder, had selected poor paintings for the French, had never taken salary from Joseph and had never worn the ‘aubergine’. It is perfectly true that it was during 1810, while he was painting the pro-French ilustrados , that he started private work on the engravings which became the Disasters of War. But poignant though they are as a commentary on war, these earlier plates are in no meaningful sense ‘patriotic’. Those plates in which a certain patriotism is evident were made later, quite possibly after the final withdrawal of the French.

Clearly, he could hear news of the war easily enough - his house was so full of chairs that scholars have suggested that it might have been a centre for tertulias - but Goya was snug enough in the capital throughout the conflict, though he had to sell some of the jewellery. He had to endure the dreadful famine of 1811-12, which gives some of its most moving plates to the Disasters series, but could welcome the entry of Wellington in August 1812 - ‘Long live Wellington and the peseta loaf’ shouted the crowds - and celebrate it with a couple of portraits.

It was in 1812, however, that he experienced a personal crisis. In June his wife Josefa died and on 28 October the

family property was divided in rather a remarkable manner. Goya’s son Javier, a colourless and mercenary man, already owned a house, but Goya made over to him his own house in the Calle de Valverde together with all his paintings and prints, his library of several hundred volumes, and some cash. Goya himself retained all the furniture, linen, silver, most of the 170,000 reales of jewellery and 126,000 reales in cash. Several of Goya’s paintings bear an X with a number, and it has been suggested, plausibly, that these numbers were the inventory numbers which Javier (Xavier) wrote on paintings he left in his father’s studio to secure his share of the division. This careful possessiveness in turn has been related to Leocadia Weiss.

Leocadia Zorrilla, one of the Goicoechea circle, had married a German merchant, but in 1811 the marriage began to break up. It seems to have broken down completely in 1812. Leocadia was to be Goya’s inseparable companion in Spain and in exile during the Restoration. Her daughter Maria del Rosario was born in 1814 and Goya’s devotion to the girl was paternal.

Evidence presented after the Restoration by the Postmaster General now makes it clear that Goya tried to run away from Madrid. At sixty-five and stone-deaf he was trying ‘to make his way to a free country’. He got as far as Piedrahita on the way to Portugal, where he was stopped by the pleas of his children and a threat from the Minister of Police to confiscate the entire family property. This flight, remarkable in itself, cannot be dated, but the coincidence of the division of the property and the form it took, the break-up of the Weiss marriage, the jealous application of Javier’s inventory numbering (alarm that Leocadia Weiss might collar the Goya property was expressed right up to the painter’s death) might suggest that it was in the late autumn of 1812 that Goya made his break for freedom. Some scholars claim to detect signs of the Leocadia liaison in paintings of majas which Goya made some time around 1812. His painting of Wellington was on public display during September 1812 and the French returned to Madrid in November. 10

Early in 1813 however they had gone for good and Goya could paint Constitution into his Allegory medallion.

He submitted a request to the Council of Regency for financial aid to paint ‘the most notable and heroic actions and scenes of our glorious insurrection against the tyrant of Europe’ in February 1814. The plea of poverty rings rather false; it may well have been pardon he was after. He was given an

allowance, and on this he painted the magnificent Second and Third of May [3,4].

About this time he was finishing the later war and famine plates of the Disasters engravings, and the great paintings grow out of the world of these private drawings. They were not well liked, however. Paintings of similar scenes by Jose Aparicio were rapturously received and were prominently displayed when the Prado museum opened. Goya’s masterpieces were stuffed away into the Prado’s reserves and did not figure in its catalogue until the 1870s. 11 The royal taste favoured such as Vicente Lopez, but there was a more serious threat. In May 1814 the purges began.

Goya’s circle of friends had already been devastated by the mass withdrawal of afrancesados in 1813; now there was another exodus. Moratin and Melendez Valdes had gone; another friend, the actor Maiquez, was imprisoned and went mad. Goya’s private drawings suddenly fill with chained prisoners, tortures, the viciousness of the Inquisition. A plan to group early and late plates on the war and the famine into a series of engravings for publication was abandoned. In May 1814 the painter had to subject himself to the process of ‘purification’, which dragged on for months. In November the Inquisition joined in and summoned him to explain the ‘obscene paintings’, the Majas, he had done for Godoy.

Not until April 1815 was he cleared.

In 1815, marking his rehabilitation with his most powerful self-portrait [1], he painted many portraits and the striking Royal Company of the Philippines. The studies of Ferdinand VII were commissioned works and rather lifeless, but many of the others, on the black background which pre-figures the Black Paintings, are remarkable. At seventy Goya seemed to be brimming with life and vigour.

This production of 1815 however was the last burst of public painting. After 1815 he withdrew into his drawings and engravings. Early in 1819 he withdrew physically to the Quinta del Sordo, an isolated house outside Madrid. There at the end of the year illness nearly killed him, and throughout the tumult of the Riego revolution he seems to have been obsessed with his Black Paintings. With the final crushing of the Constitutionalists, however, the outside world could no longer be shut out.

On 7 November 1823 Riego was executed and six days later twenty-four young men dragged Ferdinand’s chariot through Madrid to shouts of ‘Death to the Nation!’ Arrests, hangings, tortures multiplied, and in January 1824 military commissions

were set up to purge the country. Leocadia Weiss, an impetuous young woman, violent in her politics, was threatened; her eldest son Guillermo had served in the exaltado militia. 12 She seems to have gone into hiding before 1823 was out, leaving the little Rosario with the architect Tiburcio Perez, whom Goya had painted. Goya, who had already made over his house to his grandson, went into hiding in January in the house of an Aragonese, Jose Duarto y Larte. On 1 May 1824 an amnesty was proclaimed and on the very next day Goya petitioned for leave of absence to ‘take the mineral waters at Plombieres’. Ferdinand VII expressed surprise but granted permission. Late in June Goya reached Bordeaux, to be joined by Leocadia and Maria del Rosario. Moratin was there, to greet ‘the young traveller’.

■

55. The colossus, c