I think Georgia Teresa Gilmore was one of the unsung heroines of the Civil Rights Movement. She was not a formally educated woman, but she had that mother wit. She had a tough mind but a tender heart.

—THOMAS E. JORDAN

In 1956 African American playwright and actress Alice Childress published Like One of the Family: Conversations from a Domestic’s Life, a searing commentary on the status of black domestic workers. The book was a compilation of stories Childress had written in the early 1950s for the African American press, including Paul Robeson’s Freedom newspaper and the Baltimore Afro-American. These “Conversations from Life” were reflections by Mildred, a sassy and self-confident domestic, shared with her friend Marge in the intimate space of a black working-class home. They conveyed in colorful terms her dissatisfaction with domestic work. Mildred, who is thirty-two, single, and childless, recounts her experience as a day worker in white homes with wit and humor, in the storytelling tradition. In one case, Mildred’s employer effusively tells a visiting friend that Mildred is “like one of the family” and how much they love her. When the guest leaves, Mildred asks to have a word with “Mrs. C,” her employer.

“In the first place,” she chastises the woman, “you do not love me; you may be fond of me, but that is all. . . . In the second place, I am not just like one of the family at all! The family eats in the dining room and I eat in the kitchen. Your mama borrows your lace tablecloth for her company and your son entertains his friends in your parlor, your daughter takes her afternoon nap on the living room couch and the puppy sleeps on your satin spread. . . . So you can see I am not just like one of the family.”1

As an activist affiliated with the American Communist Party, Alice Childress was part of a black left cultural community focused on the plight of working-class black women. This network of activists had supported the organizing of household workers in the 1930s, and many had subsequently written political tracts about the exploitation of these workers. Although in later years Childress would attempt to distance herself from her radical past, in the 1950s this political sensibility and her own personal experience undoubtedly influenced her writing of Like One of the Family.2 Before she became a successful playwright, Childress had worked briefly as a domestic, and she reportedly based the character of Mildred on the life of her aunt. In its portrayal of a witty, sharp-minded domestic worker in 1950s New York, the book debunked myths about domestic service and exposed the dark underside of the occupation.3 The stories’ inclusion in African American newspapers around the country ensured a wide readership among household workers, some of whom reached out to Childress. As she described it: “Floods of beautiful mail came in from domestics . . . telling me of their own experiences.”4 The popularity of the essays helped foster a critique of the working conditions of African American household workers.

The publication of Childress’s book marked a critical moment in the history of domestic labor. Childress’s commentary on household labor seemed to echo a growing sentiment among black domestic workers—of a desire for recognition of their humanity and assertion of rights—that had bubbled beneath the surface for years but would soon achieve full expression. Domestic work had for decades been steeped in a racialized portrayal of African American women as the servile “mammy” figure. In part because of political organizing in the 1930s and changing views about race during World War II, new ideas were germinating. Black women’s household labor became a contested terrain on which racial politics played out in the postwar era. The emerging civil rights movement—and household workers’ participation in campaigns like the Montgomery bus boycott—provided a forum in which household workers could speak out, creating their own “conversations” about domestic labor. Their voices were critical to reshaping not only Jim Crow segregation and the dominant stereotypes of black domestics, but African American women’s status as marginalized and invisible workers.

Prior to World War II, domestic work was one of the few occupations open to African American women and was weighted with a long history of slavery, servitude, and racial oppression.5 Black women labored in the homes of white southerners, serving a cultural as well as economic function in that their subordination reinforced white racial power. Black women’s work in white homes was characterized by economic and sexual exploitation, as well as the denial of black women’s humanity and motherhood. Predatory white male employers wielded their power to sexually abuse or harass black women employed in their homes. White female employers maintained nearly complete control over the outward behavior and actions of domestics, determining what they wore, what they ate, where they ate, which bathrooms they used, and the specific ways they carried out their responsibilities. Both live-in and day workers put in extremely long hours, thus inhibiting their ability to effectively parent their own children. Moreover, the low pay, lack of benefits, and master-servant character of the relationship degraded the economic value of African American women’s labor.

The story of domestic labor in the United States is not solely an African American one. During the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries, native-born white and immigrant European women, including those of Irish, German, and Scandinavian descent, comprised a significant portion of the domestic labor force in the Northeast and Midwest. For them, as for all domestic help, the household was a site of exploitation. Irish Catholic immigrants, in particular, experienced discrimination and social marginalization stemming from stereotypes of Irish workers as uncivilized and insolent. Native-born white domestics, on the other hand, were highly desired by white employers. For most native-born and European immigrant women, however, domestic work was a temporary occupation, engaged in prior to marriage.6 Women of color—African American, Latina, Asian, and Native American—denied access to other jobs, worked as domestics out of necessity even after they had their own families. They experienced household labor as an “occupational ghetto.”7 Throughout the former slave South, African American women were the primary domestic-service labor force. In the Southwest, Mexican and Mexican American women, and in the West, Japanese and Chinese women, as well as some Asian men in the nineteenth century, were employed as household servants.8

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, industrialization and the rise of the service sector generated more opportunities for working-class white women, who rapidly exited domestic work for jobs in garment factories, department stores, the telephone industry, and offices.9 The curtailment of European immigration in the 1920s further limited the number of domestics available from across the Atlantic. These trends resulted in a shortage of white and European-immigrant domestic workers, and women of color became the vast majority of domestic workers in all regions of the country. From 1900 to 1950 the number of white female household employees declined from 1.3 million to 542,000. The number of nonwhite domestic workers increased from 567,000 to 796,000.10 Attempts to recruit working-class white women as well as migrant domestic workers from Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and Barbados were only marginally successful. Northern employers more commonly turned to agencies that recruited African American women from the South.11 As the number of private household workers declined overall, African American women became a greater proportion of the workforce. In 1900 black women constituted 28 percent of domestic workers; by 1950 they were 60 percent.12

African American women’s predominance in the field of household labor tied the occupation more closely to the history of race and slavery, and this fueled a battle between black and white communities to define the racial politics of domestic labor.13 Southern whites—and many northern whites—romanticized the mammy figure, an African American woman who represented the ideal loyal servant and embodied a harmonious view of race relations.14 Dominant white society used the stereotype of the mammy to justify African American women’s status as household laborers and to reconstitute racial hierarchies. For the black community, domestic service became a powerful symbol of racial exploitation and a platform for the assertion of black women’s rights. Middle- and working-class African Americans challenged both the constellation of ideas that associated African American women with household labor and the social and economic arrangements that confined African American women to this occupation. Household workers themselves turned to both the legacy of slavery and the nature of their work to formulate critiques of black working-class life. Thus black domestic-worker organizing had its own strategic legacy: it did not merely play a supportive role in the struggle for black freedom but generated new tactics and ideas of black activism in resisting the fundamental arrangements of white supremacy. The divergence in perspectives between blacks and whites with respect to domestic labor reflected and shaped broader discourses on race.

In the early twentieth century, when a Ku Klux Klan march of twenty thousand people paraded through the streets of the nation’s capital, when African Americans were systematically denied the right to vote through poll taxes, literacy tests, and overt threats, and when white mobs rampaged through black communities inflicting terror and deadly violence, some white southerners sought to rewrite the history of slavery and race relations through the elevation and reverence of the mammy figure. Indeed, the period from the 1890s through the 1940s experienced a “Mammy craze,” in the words of the scholar Cheryl Thurber.15 The mammy became a source of comfort when racial strife was heightened, and provided concrete evidence for whites that the paternal southern order made African Americans happy. A white construction emerging from the defense of slavery in the 1830s, the mammy symbolized a content and loyal household worker who nurtured and protected white children. As historian Kimberly Wallace-Sanders puts it, “mammy” was “a code word for appropriately subordinate black behavior.”16 The mammy figured prominently in advertising, the arts, and literature at the beginning of the twentieth century, as white northerners and southerners attempted to put the divisiveness and resentment of the Civil War behind them and mask contemporary racial violence. The black mammy issued from a fictionalized tale of stable race relations marked by mutual dependence and familial love. In 1936, Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind generated a national commercial audience for the stereotyped figure; the character of Mammy is a caricatured, heavyset black servant who demonstrates unwavering loyalty to the O’Hara family over three generations. The astounding success of the book and film suggests how comfortable white Americans were with the idealized image of the black maid.

White southerners paid homage to the mammy figure in countless ways. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization of white southern women whose name implies a commitment to the vision of a slave South, went so far as to launch a campaign in 1924 to build a federally funded national “black mammy” monument in the nation’s capital. African American activists, many of whom were part of the New Negro cultural movement promoting racial pride, furiously opposed the congressional bill, claiming that the proposed monument glorified slavery and black subservience.17 For them the mammy figure was a distortion of the historical record, reflecting a paternalism that continued to shape domestic worker–employer relations into the twentieth century. African American activist Mary Church Terrell, one of the most outspoken opponents of the proposed monument, wrote that if it were built, “there are thousands of colored men and women who will fervently pray that on some stormy night the lightning will strike it and the heavenly elements will send it crashing to the ground.”18 African American opposition to the legislation carried the day. The bill passed the Senate but died in the House, and the monument was never built.

As difficult as the economic collapse of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression was for many Americans, the situation for black domestic workers was dire. With twenty-five percent of the nation unemployed, work was especially hard to come by and, for those lucky enough to find a job, exploitation was rampant. As family incomes dwindled, employers fired domestic workers, reduced rates of pay, or simply squeezed more work out of their employees.

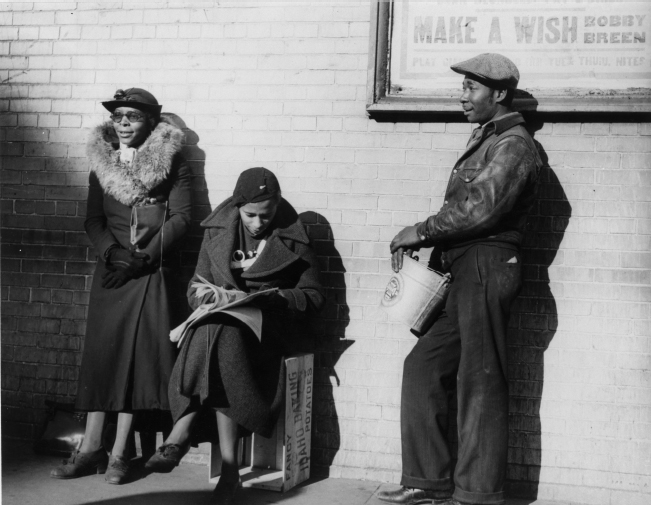

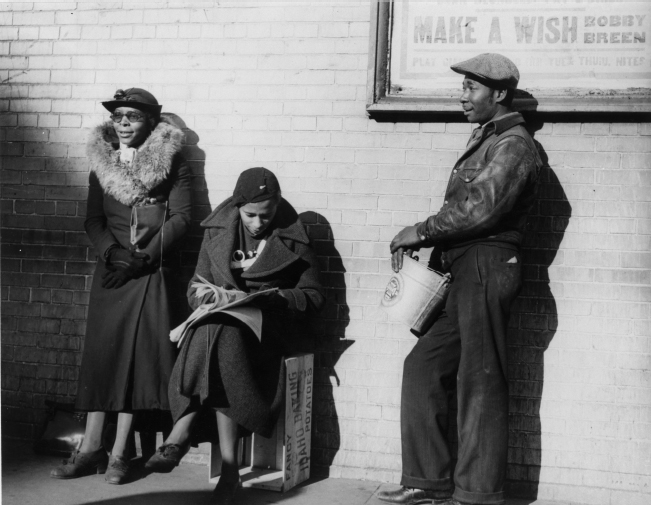

Through their writing and activism, a group of radical black women drew public attention to the plight of African American women working as day laborers during this period. In 1935 investigative journalist Marvel Cooke and activist Ella Baker coauthored a widely circulated article about what they called the “slave market” of domestic labor. The article, published in the NAACP’s magazine, Crisis, cast light on an estimated two hundred informal markets in New York City—essentially street corners—where African American women waited in hopes of being hired for the day by white employers. “Rain or shine, cold or hot, you will find them there—Negro women, old and young—sometimes bedraggled, sometimes neatly dressed . . . waiting expectantly for Bronx housewives to buy their strength and energy.” Cooke and Baker highlighted the vulnerability of these workers: “Often, her day’s slavery is rewarded with a single dollar bill or whatever her unscrupulous employer pleases to pay. More often, the clock is set back for an hour or more. Too often she is sent away without any pay at all.”19

Over the next several years, Cooke, often posing as a domestic worker, wrote a series of articles in the New York Amsterdam News exposing the harrowing experiences of the city’s black domestic workers. Because of public attention to the condition of household laborers, New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia established the Committee on Street Corner Markets, outlawed the hiring of women off the street, and opened two employment offices to combat exploitative practices. In the postwar period, Cooke carried on her crusade to document the ongoing abuses of domestic workers, writing a five-part series on domestic work in 1950 for the leftist newspaper the Daily Compass. Despite modest gains made during the war years, Cooke argued that slave markets had reappeared and that African American women were once again experiencing declining job opportunities.20

Street-corner markets became a graphic example of racism and the legacy of slavery. The image of poor African American women being subjected to a latter-day slave market and mistreated by white employers with impunity fueled a commitment to reform. Stories about the abuses were repeated and passed down in African American families. Some three decades after the 1930s slave markets, these stories would be claimed and retold by household workers who were developing a mass movement to transform the occupation.

Bronx Slave Market, 170th Street, New York City, 1938

(Smithsonian American Art Museum, photograph by Robert McNeill)

Cooke was part of a network of African American women activists that included Alice Childress and Claudia Jones, a journalist with the Communist Party USA’s newspaper the Daily Worker. Esther Cooper Jackson, who had worked with the Southern Negro Youth Congress and wrote a master’s thesis challenging the widespread belief that household workers could not be unionized—the first study of its kind—also participated in this circle of activists; as did Louise Thompson Patterson, a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance who led a group of black artists and intellectuals to the Soviet Union in 1932. These mostly middle-class black women, politicized during the economic turmoil and mass mobilization of the 1930s, were members of the Communist Party.21 They established friendships and collaborated on building organizations for social change such as Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a short-lived early 1950s black radical feminist group that made domestic work central to its agenda. They worked with the National Negro Labor Council, which was committed to organizing domestics, and formulated an intellectual analysis of domestic labor that challenged the strictly class-based Marxist analysis. These black feminists produced a body of work that theorized the place of domestic labor in working-class politics and social change. In 1936 Patterson, examining the interconnections of race, class, and gender, published a groundbreaking essay in the Communist Party magazine Woman Today. “Toward a Brighter Dawn” analyzed the “triple exploitation” domestic workers experienced, “as workers, as Negroes, and as women,” and called for unionization.22 Similarly, Jones, in a 1949 article, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!” argued that “Negro women . . . are the most oppressed stratum of the whole population.” She insisted that slave markets and mammy stereotypes that trapped African American women in a cycle of exploitation “must be combatted and rejected.” She also argued that household workers exhibited the revolutionary and leadership potential necessary for political organizing.23 The historian Mary Helen Washington believes that Childress’s Like One of the Family was a literary response to Jones’s call for thinking about household workers as political agents.24

Cooke, Jones, and other black feminists supported groups such as the New York–based Domestic Workers Union (DWU) led by Dora Jones, an African American domestic worker from Sunnyside, Queens. Formed in 1934, the DWU was part of a spate of domestic-worker organizing in the 1930s, one of dozens of such formations around the country.25 With bases in several New York City neighborhoods, the DWU had an estimated one thousand African American and Finnish members, but soon became almost entirely black. They organized in public parks, apartment buildings, and in the “slave marts” to establish decent wage rates and pressure other workers to refuse to work for less. According to historian Vanessa May, organizing was an opportunity for household workers to speak for themselves, and union members created a “community of shared experience and suffering.”26 DWU campaigned to pass state legislation to provide minimum wage and workers’ compensation protections for household workers. Participation seemed to have a tangible effect on those women who joined. Esther Cooper, in her 1940s master’s thesis on domestic-worker organizing, recounted the views of union members: “Before I belonged, I quit two jobs ’cause I couldn’t stand it, and then spent a month on the ‘slave market’ working by the day for 25c an hour. . . . I ain’t never been sorry that I’m a Union member and I’ll fight for the Union all I can.”27 In 1936 DWU affiliated with the Building Service Employees International Union (BSEIU), a member of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).28 Under the slogan “Every domestic worker a union worker,” DWU opened a hiring hall, required nonunion workers to join the union, and insisted that employers sign contracts with its members. The union built alliances with labor and civil rights groups and with the Women’s Trade Union League to lobby for minimum wage and workers’ compensation for domestic workers in New York State. It advocated for individual workers and organized mass meetings. Although hampered by a shortage of funds, opposition from white housewives, and a competitive labor market, DWU continued to operate until at least 1950, after which there is little information about its activities.

The DWU prefigured the upsurge of domestic-worker organizing that would transform the political landscape in the postwar era. Domestic work assumed an important place in the politics of black left feminists of this period.29 Although few were domestics themselves, they were immersed in a world where the dividing line between the African American middle class and working class was easily traversed; many, like Alice Childress, had family members who were household workers or were working class themselves. These activists wrote about the importance of domestic work for African American women, but also articulated the radical potential of this workforce, helping to foster in domestic workers a subjectivity of dignity and resistance. They unequivocally rejected the mammy stereotype and placed domestic work firmly within discussions of class, race, and gender. They suggested that, as the most oppressed labor sector, domestic workers’ mobilization offered the possibility of liberating the entire working class. These black feminists saw black domestic labor not simply as evidence of exploitation, but as an avenue for political mobilization. The political and cultural connections between black activists and intellectuals and their working-class and poor counterparts formed the basis of an alliance as the domestic workers’ rights movement burgeoned in the postwar period.

The black household workers that made up the domestic workers’ rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s probably hadn’t read Claudia Jones or Marvel Cooke. They may not even have heard of them. Indeed, Cold War repression and witch hunts for Communists and Communist sympathizers ensured the marginalization of these black women activists and blunted their connection to the emerging civil rights movement.30 But domestic workers who organized in the postwar period drew on the same history and collective knowledge.

Although the postwar period brought the Cold War and a stifled political climate, it also generated critiques of the racial status quo. World War II ushered in dramatic political and economic changes and new sensibilities about race that shaped the politics of domestic labor. A newfound sense of freedom and political possibility—no doubt bolstered by anticolonial movements and the rhetoric of self-determination—became evident among African Americans who engaged in the black freedom movement in the 1950s. And domestic workers were a critical component of that movement. Although many of its vignettes were written earlier, Alice Childress’s Like One of the Family was published in 1956, in the midst of the Montgomery bus boycott, a campaign that showcased the power and resistance of domestic workers.

Perhaps no civil rights protest in the 1950s better reflected emerging domestic worker agitation than the Montgomery bus boycott. Thousands of working-class black women in Montgomery, Alabama, many of whom were household workers, participated in and supported the boycott, a protest campaign to end racial discrimination in the city’s public transportation system. According to one study, at the start of the protest over half of black women workers in Montgomery were employed in white homes.31 These women relied on public transportation on a daily basis to get to their places of employment. Without their support, the bus boycott, quite simply, would never have succeeded.

Middle-class black women were critical to initiating and sustaining the protest. The Women’s Political Council, a civil rights group founded in Montgomery, had been meeting for years and discussing a possible citywide bus boycott. It had a distributional network in place and was ready to launch such a protest at a moment’s notice.32 Martin Luther King Jr. would become the primary spokesperson of the yearlong boycott, bringing him to national attention. Less prominent in the boycott’s retelling are the working-class and poor black women who were the grassroots base of the movement, whose voices are often muted. The iconic black maid dutifully supporting the boycott by refusing to ride the buses after a long and exhausting workday is an image closely associated with the national narrative of the boycott. In some ways the representation of the maid in the movement fed popular stereotypes of the loyal black mammy—although in the service of the movement rather than the white family. She is strong but not confrontational; tired but determined, as evidenced in the oft-repeated quote attributed to Mother Pollard, a poor elderly black woman who, when asked if she was tired, replied: “My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.”

In reality, domestic workers played a significant and complicated role in the boycott. They filled the pews at mass meetings and served as the foot soldiers that made the boycott a success, and they also exhibited leadership by raising money and mobilizing others in the community to support the campaign. They used their domestic skills in the service of the protest (by selling food they had cooked to raise funds, for example), and the political leverage they gained from civil rights activism in their day-to-day dealings with their employers. The disruptions of the boycott transformed their relationships with their employers, emboldening the workers and fostering a sense of militancy.

With the arrest of Rosa Parks, most Montgomery maids knew their time had come. In early 1956, a couple of months after the boycott began, researchers from Nashville’s historically black Fisk University conducted interviews of household workers in Montgomery under the supervision of African American sociologists Preston and Bonita Valien. The racial background of the interviewers is not specified, but the recorded black vernacular of the interviewees, seemingly exaggerated in the original transcripts, reflects class or intellectual bias. Nevertheless, the content of the interviews is an important window into a sector of the African American community and captures the sentiment of household workers at the start of the boycott.

One of the workers interviewed, Allean Wright, a cook in her late forties, spoke of her joy upon hearing about the boycott: “I felt good, I felt like shoutin’ . . . because the time had come for them to stop treating us like dogs.”33 The hardship of domestic labor as well as ongoing mistreatment had taken its toll. “This stuff has been going on for a long time,” remarked Beatrice Charles, a forty-five-year-old maid. “To tell you the truth, it’s been happening ever since I came here before the war. . . . But . . . in the last few years they’ve been getting worse and worse.”34 Another domestic worker, in her late sixties, explained: “Honey, I have washed and iron[ed] clothes till my legs and body ached. . . . [What] does it matter if . . . I still ache, ’cause my mind is now at peace with God, ’cause we’re doing what’s right and right always win out.”35 Gussie Nesbitt, a fifty-three-year-old domestic and a member of the NAACP, echoed this sentiment. “I walked because I wanted everything to be better for us. Before the boycott, we were stuffed in the back of the bus just like cattle. And if we got to a seat, we couldn’t sit down in that seat. We had to stand up over that seat. I work hard all day, and I had to stand up all the way home, because I couldn’t have a seat on the bus. And if you sit down on the bus, the bus driver would say, ‘Let me have that seat, Nigger.’ And you’d have to get up.”36 Irene Stovall had ridden the buses for fifteen years and had been at the bus stop talking about the poor treatment of African American riders when she first heard about the boycott. “When I got home,” she recalled, “Junior came runnin’ [in] with the paper, ‘Momma they say don’t ride the buses.’ I said, Lord you . . . answered my prayer.”37 So despite the physically taxing nature of their labor and the sacrifices they would have to make to participate in the campaign, domestic workers expressed unequivocal support for the boycott.

Rosa Parks, whose arrest initiated the boycott, became the symbol of the mistreatment of African American women in the segregated South. One domestic worker observed that they were boycotting the buses because Montgomery was a “Jim Crow” town, and they “put one of our [re]spectable ladies in jail.” She continued, saying that she could only take so much and “soon you [get] full.”38 Beatrice Charles explained: “I had heard about Rosa Parks getting put in jail because she would not get up and stand so a white man could sit down. Well, I got a little mad, you know how it is when you hear how white folks treat us.” After she heard about the boycott, Beatrice recalled: “I felt good. I said this is what we should do. So I got on the phone and called all my friends and told them, and they said they wouldn’t ride.”39

The boycott demonstrated a level of cross-class alliance between the protest’s middle-class organizers and leaders, who saw their fate tied to the larger black community, and the workers whose support for the boycott was critical to its success. Dealy Cooksey, a domestic worker about forty years old, described the tension this alliance created in her relationship with her employer. “Dealy, why don’t you ride the bus?” her employer, who drove her home most days after work, asked her shortly after the boycott began. Reverend King is “making a fool out of you people.” Dealy replied angrily: “Don’t you say nothing about Rev. King. . . . He went to school and made something out of hisself, and now he’s trying to help us. Y’all white folks done kept us blind long enough. We got our eyes open and ain’t gonna let you close them back. I don’t mean to be sassy, but when you talk bout Rev. King I gets mad. Y’all white folks work us to death and don’t pay nothing.” Her employer retorted: “But Dealy, I pay you.” Dealy challenged her: “What do you pay, just tell me? I’m ashamed to tell folks what I work for.” Dealy was not about to be swayed by her employer’s words: “I walked to work the first day and can walk now. If you don’t want to bring me, I ain’t begging, and I sure ain’t getting back on the bus and don’t you never say nothing about Rev. King.”40

Dealy’s no-nonsense attitude toward her employer is echoed by many of the domestic workers interviewed. In speaking about the protest, domestic workers were less constrained by notions of decorum and propriety than the middle-class leaders of the boycott. In contrast, the question of respectability occupied the minds of boycott leaders from the outset, especially regarding who would become its symbol. This had to be, they argued, an upstanding citizen of the community, someone beyond reproach. Despite her working-class status, Rosa Parks’s genteel and soft-spoken demeanor more easily fit into traditional standards of respectability and she was carefully cultivated to become that symbol even to the point of rewriting her own personal history.41 And she was chosen at the expense of others who had been arrested for violating local segregation laws. Claudette Colvin was a young black teenager who was arrested several months before Parks for violating the city’s segregation laws. Even though Colvin was a straight A student, she was visibly pregnant at the time of the arrest and that, coupled with her working-class status—her mother was a maid and her father a yard worker—made her a less-than-ideal symbol of black protest. Although city leaders decided not to call a boycott, Colvin’s arrest garnered a wellspring of support within Montgomery’s black community. A few months later, in October 1955, Mary Louise Smith, an eighteen-year-old maid, was arrested and fined for refusing to give her seat to a white woman.42 Smith’s working-class status also proved to be an obstacle to her becoming a symbol of black resistance in Montgomery. These decisions reflected the politics of respectability that shaped the Montgomery bus boycott and the civil rights movement more broadly.43

The upstandingness of Rosa Parks, the dignified restraint of Martin Luther King, the self-possession of well-dressed college students taking part in lunch counter sit-ins—all are examples of movement leaders making their public claim to political rights.44 But domestic workers and other activists at the grassroots level provided an important counterpoint to their middle-class counterparts: they didn’t hesitate to tell it like it is, and their testimony reveals an awakening political sensibility.45

The experience of Willie Mae Wallace, a store cleaner in her thirties, may not have been typical, but it is indicative of the fed-up attitude of some working-class people who rode the buses in segregated Montgomery. She explained: “One morning I got on the bus and I had a nickel and five pennies. I put the nickel in and showed him the five pennies. You know how they do you. You put five pennies in there, and they say you didn’t. And do you know that bastard cussed me out. He called me bastards, whores and when he called me a mother F––, I got mad and I put my hand on my razor. I looked at him and told him ‘Your mammy was a son-of-a-bitch, that’s why she had you bitch. And if you so bad, get up out of that seat.’ I rode four blocks, then I went to the front door and backed off the bus, and I was just hoping he’d get up . . . but he didn’t say nothing. Colored folks ain’t like they use to be,” she went on to say. “They ain’t scared no more. Guns don’t scare us. . . . I don’t mind dying, but I sure Lord am taking a white bastard with me.”46

The militant attitudes of domestic workers carried over into their work relationships. The boycott emboldened them to speak out. The conventional wisdom among white employers held that domestic workers were meek and submissive and that the boycott was a result of outsider agitation. Employer interviews seem to confirm this. As Mrs. H. N. Blackwell, for example, asserted, “I can tell you that the Negroes I have talked to about it aren’t interested in the issue and say they wish it hadn’t come up. . . . Certainly none of the maids who work out here would cause any trouble.” She was convinced that refusal to ride the buses was not their own decision: “You know they are superstitious, emotional people and if their preachers tell them something will happen if they ride the buses I believe that many of them might be afraid.”47 According to Mrs. Lydia S. Prim, “Everything was all right before those radicals came in and started stirring up trouble.”48 This attitude was also reflected in certain sectors of the black community. In the days after Rosa Parks was arrested, civil rights leader E. D. Nixon charged black ministers to publicly support the boycott when he told them, “It’s time to take the aprons off.”49 The gendered language was intended to shame African American men into taking a stronger stand against white oppression. Fear was a powerful force that shaped what many, including King, described as complacency within Montgomery’s black community. Interviews with domestic workers suggest that concerns over losing their jobs had discouraged some from adopting a more visible role.

As the Montgomery protest garnered national attention, domestic workers who had been hesitant to speak out gained strength from the community mobilization. Willie Mae Wallace, a store cleaner, experienced ongoing harassment during the boycott from a white woman who worked with her. When her coworker asked if she rode the bus, Willie Mae responded that she did not and was not going to. The woman gave her a hard time all day. Finally, Willie Mae confronted her. “I told her if she didn’t like the way I did it to do it herself. She didn’t hire me and, she sure couldn’t fire me. She bristled all up like she wanted to hit me. I said, ‘Look, my ma was black and she’s resting [deceased] and the white woman ain’t been born that would hit me and live. The police might get me, but when they do, you’ll be three D: Dead, Damned and Delivered.’”50

The husband of Irene Stovall’s employer was a city bus driver. One evening the employer told her to come by and pick up some bacon grease, but “she told me don’t let her husband see it because he had instructed her not to give Irene anything else.” Then, she asked: “Irene, what happened at the meeting last night?” When Irene responded that they sang and prayed, her employer got angry and called her a liar. “Now listen, I know we [sang] and prayed, and if you don’t believe me, YOU go to the meeting for yourself.” Irene was furious that her employer would try to get information out of her and said to herself: “She must take me for a fool—think I’ll come back here and puke everything my folks says to her, and then for some little old stinking bacon grease.” Her employer shot back: “Irene, I didn’t know you was so damn stupid. . . . I didn’t know you were scared to ride the bus.” Irene was so infuriated, she told her employer off. “I told her that I was not scared to ride the bus, I’d ride if I want to, but her husband never would get a dime from me no more.” She explained that she joined the boycott because she wanted to, and that she remained in the South in order to help her people. Her employer responded: “You know we could starve y’all maids for a month.” Irene, using the full weight of her words as well as her two-hundred-pound frame to her advantage, retorted: “I pity anybody who waits fur me to starve. They’ll be waiting for a long time.” Despite the heated exchange, Irene’s boss continued to pay her wages and bus fare, but Irene decided, “I better quit before I have to beat her . . . She heard me say [a] heap of time that if you hit me, I hit back and I ain’t big for nothing.”51

The complexity of the mistress-maid relationship came to the fore during the boycott. In their actions, domestic workers disproved the loyal mammy myth of popular culture, agitating and maneuvering to improve their lot. The boycott created an opening for workers to express their political views and to question the terms of their employment. White employers expressed surprise at the dissatisfaction vocalized by domestics. And many were taken aback by the overt militancy exhibited by their workers. At the same time, many employers inadvertently aided the boycott by driving their maids to work or giving them cab fare, because they depended upon domestics to keep their households running. This became evident when the mayor of Montgomery, Tacky Gayle, urged white housewives not to drive their maids to and from work. White employers responded angrily and suggested that the mayor come do their household chores for them.52 Even at the expense of aiding the boycott, employers were not willing to do without their maids. Domestic workers were indispensable to the white community and played a pivotal role in the effort to establish a new politics of race relations in Montgomery.

The interviews of Montgomery’s domestic workers make clear black domestics’ desire to challenge the status quo. The boycott, which proved an overwhelming success, emboldened domestic workers in their workspaces as well as in public spaces, even though they were isolated employees. The key issues that plagued them in the workplace—unfair treatment and denial of their humanity—were also in play on the city buses. Domestic workers not only supported the boycott and made it part of their own struggle, but, as Georgia Gilmore’s story illustrates, they also provided leadership.

Georgia Gilmore, who moved to Montgomery in 1920, became a leading advocate for household laborers. She lived in Centennial Hill, a middle-class African American community with a thriving black business sector on Montgomery’s east side, near the state capitol. A large woman who weighed over three hundred pounds, Gilmore was a single mother of six. Like most black women in the South, she earned her living through her knowledge and skill as a domestic—although she did so in multiple settings. Gilmore worked as a nurse and a midwife, delivering babies in the black community. She was employed as a cook in a cafeteria and also a maid in private households.53 She put those skills to use during the Montgomery bus boycott, raising money, feeding demonstrators, and creating meeting spaces, yet her name is relatively unknown today.

Gilmore understood that household workers’ refusal to ride the buses was indispensable to the boycott’s success. “Because you see they were maids, cooks,” she said. “And they was the one that really and truly kept the bus running. And after the maids and the cooks stopped riding the bus, well the bus didn’t have any need to run.”54 Her support for the boycott was rooted in part in her own experiences on the city buses. As was typical for working-class black people in Montgomery, Gilmore didn’t own a car. She was a regular bus rider with few other transportation options. Gilmore shared her experience of riding on the city buses when she testified at the 1956 trial of Martin Luther King: “Many times I have been standing without any white people on the bus and have taken seats, and when the driver sees you he says, ‘You have to move because those seats aren’t for you Negroes.’”55 Gilmore’s elderly mother also encountered difficulties. Gilmore recounted one experience that not only demonstrated the callous disregard for her mother’s physical limitations, but the vicious racial insults that accompanied it: “She was an old person and it was hard for her to get in and out of the bus except the front door. The bus was crowded that evening with everybody coming home from work. She went to the front door to get on the bus, and this bus driver was mean and surly, and when she asked him if she could get in the front door he said she would have to go around and get in the back door, and she said she couldn’t get in, the steps were too high. He said she couldn’t go in the front door. He said, ‘You damn niggers are all alike. You don’t want to do what you are told. If I had my way I would kill off every nigger person.’”56

In October 1955, before Rosa Parks’s arrest, Gilmore had another in a long series of unpleasant encounters with city bus drivers, which prompted her to begin her own one-woman boycott. During Friday-afternoon rush hour, Gilmore boarded a packed Oak Park bus. There were two white passengers; the rest were African Americans. Although she didn’t know the driver’s name, she recognized him. “This bus driver is tall, hair red, and has freckles, and wears glasses. He is a very nasty bus driver.” After she paid her fare, the driver told her to get off the bus and enter through the rear door. She pleaded with him to let her stand there, since she was already on the bus and most of the riders were African Americans in any case. The driver refused. “So, I got off the front door and went around the side of the bus to get in the back door, and when I reached the back door and was about to get on he shut the back door and pulled off, and I didn’t even ride the bus after paying my fare. So, I decided right then and there I wasn’t going to ride the busses any more. . . . And so I haven’t missed the busses because I really don’t have to ride them. . . . I haven’t returned to the busses—I walk.”57 This kind of individual protest was not unheard of among black women in Montgomery before the bus boycott.

A few months after her decision to stop riding the city buses, Gilmore heard a radio broadcast announcing the arrest of Rosa Parks. At the time, she was working at a white-owned segregated restaurant in Montgomery, the National Lunch Company. After a hugely successful one-day boycott of Montgomery’s buses the Monday after Parks’s arrest, a community meeting was convened to discuss a course of action. Gilmore was one of several thousand people who attended the evening gathering at Holt Street Baptist Church. Organizers had to set up speakers to accommodate the overflow crowd. Gilmore was moved by what she heard, especially the speech by the young Reverend Martin Luther King, who declared in his address, “There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression.” Gilmore was impressed: “I never cared too much for preachers, but I listened to him preach that night. And the things he said were things I believed in.”58 The community members in attendance overwhelmingly supported the decision to continue the boycott indefinitely under the leadership of the newly formed Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA).

Gilmore, of course, had no intention of riding the buses. She was fed up, and welcomed the opportunity to engage in collective protest. She explained: “Sometime I walked by myself and sometime I walked with different people, and I began to enjoy walking, because for so long I guess I had this convenient ride until I had forgot about how well it would be to walk. I walked a mile, maybe two miles, some days. Going to and from. A lot of times, some of the young whites would come along and they would say, ‘Nigger, don’t you know it’s better to ride the bus than it is to walk?’ And we would say, ‘No, cracker, no. We rather walk.’ I was the kind of person who would be fiery. I didn’t mind fighting with you.”59

The Monday- and Thursday-night meetings, part organizing committee, part solidarity rally, became a regular occurrence in Montgomery as the boycott dragged on. The large crowds, led by middle-class ministers but made up overwhelmingly of black working-class women, were enthusiastic and lively. Gilmore showed up almost without fail to the gatherings.

As became clear early on, the boycott was expensive to run and maintain. Coordination was a massive undertaking and included fundraising, publicity, legal representation, security patrols, as well as the providing of alternative transportation in the form of an organized carpool for protesters. The Montgomery Improvement Association needed money to operate the carpool and assist people who had been arrested, fined, or fired for participation in the protest. The carpool was an extensive citywide network with three hundred vehicles and forty-two pickup and drop-off points. Coordinators rented or borrowed vehicles, hired drivers, and paid for gas and insurance. Gilmore looked for a way that she could best help out. According to Johnnie Carr, a member of the Women’s Political Council and longtime friend of Rosa Parks: “Georgia just got it into her mind that she was going to raise money for the Movement. And if Georgia was raising money, she was doing it through food.”60 Gilmore recounted: “We collected $14 from amongst ourselves and bought some chickens, bread and lettuce, started cooking and made up a bundle of sandwiches for the big rally. We had a lot of our club members who were hard-pressed and couldn’t give more than a quarter or half-dollar, but all knew how to raise money. We started selling sandwiches and went from there to selling full dinners in our neighborhoods and we’d bake pies and cakes for people.”61

Gilmore founded the Club from Nowhere, an organization of maids, service workers, and cooks seeking to aid the boycott. The name was an attempt to shield members from the consequences of openly supporting the boycott. “Some colored folks or Negroes could afford to stick out their necks more than others because they had independent incomes,” Gilmore explained, “but some just couldn’t afford to be called ‘ring leaders’ and have the white folks fire them. So when we made our financial reports to the MIA officers we had them record us as the money coming from nowhere. ‘The Club from Nowhere.’”62 Only Gilmore knew who made and bought the food and who donated money. The underground network of cooks went door-to-door selling sandwiches, pies, and cakes, and collecting donations. The proceeds were then turned over to boycott leaders. Donations came from whites as well as blacks. That “was very nice of the people because so many of the people who didn’t attend the mass meetings would give the donation to help keep the carpool going.”63

The campaign spread to other neighborhoods. According to Gilmore: “Well, in order to make the mass meeting and the boycott be a success and that keep the car pool running, we decided that the peoples on the south side would get a club and the peoples on the west side would get a club.”64 The various groups competed, each trying to raise more money than the other. “When we’d raise as much as $300 for a Monday night rally, then we knowed we was on our way for $500 on Thursday night.”65 Gilmore offered the money at the Monday-night mass meetings to wild cheers and thunderous applause.

When Gilmore’s boss at the National Lunch Company learned of her activism, she was fired and blacklisted. Unfortunately, retaliation was not uncommon during the boycott; both E. D. Nixon and Martin Luther King had their homes bombed, and Rosa Parks lost her job at the department store where she worked as a seamstress. Gilmore had little choice but to turn these impediments into opportunities. Martin Luther King encouraged her to cook out of her own home and even helped her financially.66 When the city tried to shut her down, King helped her remodel her kitchen to meet city standards. Gilmore awoke at four o’clock in the morning and, in her small kitchen, began preparations to make stuffed pork chops, meat loaf, barbecued ribs, fried fish, spaghetti in meat sauce, collard greens and black-eyed peas, stuffed bell peppers, corn muffins, bread pudding, and sweet potato pies. She cooked lunch daily out of her kitchen for people involved in the boycott, including King.67 Although she had no restaurant seating, people showed up at her house to eat, squeezing around the dining room table or sitting and eating on the couch. King, who called her Tiny, frequented her house, often bringing guests or holding clandestine meetings at her home.68 According to Reverend Al Dixon: “Dr. King needed a place where he could go. You know, he couldn’t go just anywhere and eat. He needed someplace where he could not only trust the people around him but also trust the food. And that was Georgia’s.”69 Gilmore’s dining room table became a meeting space connecting blacks and whites, working class and middle class in the civil rights movement: professors, politicians, lawyers, clerical workers, police officers. She served such well-known figures as Morris Dees of the Southern Poverty Law Center, Lyndon Johnson, and John Kennedy. In this context, cooking became a conduit for political connections.70

Reverend Thomas E. Jordan, pastor of Lilly Baptist Church, reflected on Gilmore’s role in the boycott: “I think Georgia Teresa Gilmore was one of the unsung heroines of the Civil Rights Movement. She was not a formally educated woman, but she had that mother wit. She had a tough mind but a tender heart. You know, Martin Luther King often talked about the ground crew, the unknown people who work to keep the plane in the air. She was not really recognized for who she was, but had it not been for people like Georgia Gilmore, Martin Luther King Jr. would not have been who he was.”71

Like other domestic workers, Gilmore was less constrained by social niceties than movement leaders. As Alabama State professor Benjamin Simms, who served as head of the MIA’s transportation committee, commented: “She’s a sweet woman, but don’t rub her the wrong way. Would you believe that this charming woman once beat up a white man who had mistreated one of her children. He owned a grocery store, and Mrs. Gilmore marched into his place and wrung him out.”72

Black domestic workers like Gilmore were service workers with a particular set of skills that could be utilized for political mobilization. Thus they exhibited the political agency that Claudia Jones anticipated. Their struggle, however, was not for class overthrow, as the black radical feminists of the 1930s and 1940s predicted, but transformation of the power structure, on city buses and in their workplaces. They sought to build cross-class alliances and carve out spaces of autonomy and mutual respect for the South’s working-class black women. Household workers were the quintessential “outsiders within,” to use Patricia Hill Collins’s term—privy to the most intimate details of white family life yet not a part of that family.73 Their social status and proximity to the white domestic sphere enabled them to wield a different kind of power in engaging in community action. Their intimate relationship with white households granted them access and knowledge unavailable to others. During the Montgomery bus boycott, maids surreptitiously gathered information from the white community. Bernice Barnett argues: “The maids, cooks, and service workers of the [Club from Nowhere] also had access to information in the homes of their White employers. As they went invisibly about their domestic work, the [members of the Club] were alert to news about the strategies and tactics of the White opposition.”74 Domestic workers used the very elements of domestic work—their marginalization, their insider status, their access to the white domestic sphere, their culinary skills—as a basis for subversive activity. They were instrumental in unsettling the white community and pushing for more egalitarian race relations. They made clear that the boycott was not only about equal rights, but about respect.75 Their claim for respect and political engagement posed a fundamental challenge to the long-standing “mammy” stereotype. Even though they had few labor rights, black domestic workers possessed power within their workplace that enabled them to exercise leverage over their employers.

In one of her “conversations,” Alice Childress writes about the benefits of unionization and the need for domestic workers to band together. “Honey,” says Mildred, her protagonist, “I mean to tell you that we got a job that almost nobody wants! That is why we need a union! Why shouldn’t we have set hours and set pay just like busdrivers and other folks, why shouldn’t we have vacation pay and things like that?” And if employers don’t like the terms of the work and want to hire a nonunion person? “Well, then the union calls out all the folks who work in that buildin’, and we’ll march up and down in front of that apartment house carryin’ signs which will read ‘Miss So-and-so of Apartment 5B is unfair to organized houseworkers!’ . . . The other folks in the buildin’ will not like it, and they will also be annoyed ’cause their maids are out there walkin’ instead of upstairs doin’ the work. Can’t you see all the neighbors bangin’ on Apartment 5B!”76

In her writings, Childress foreshadowed a new kind of resistance among black domestic workers. While the Montgomery bus boycott encouraged household workers to mobilize in support of the boycott and created a space to express dissatisfaction to their employers, it also prompted household workers in other parts of the country to organize independently—as workers—to transform an occupation that was central to working-class black women’s lives and the history of race in modern America.