The Satisfaction of Nations

[The] big thing that’s missing is a technocratic understanding of the facts, where things are working and where they’re not working.

BILL GATES, quoted in the New York Times

THE PREVIOUS CHAPTER, weighing the rivals on their own materialist terms, sought the effects of corporatism (and socialism) on the material economy—mainly on employment and productivity. Yet there is a nonmaterial dimension in a modern economy, as in modern life in general. Much of what is most valued about participating in a relatively modern economy is the challenge and experience it usually offers, and the intuitions and ideas it excites, rather than the material goods and services produced. As emphasized from the start, the modern economy is a vast imaginarium, a virtual laboratory in which to dream up and try out ideas. The modern revolution in arts and letters mirrored the new experience sought and widely found in modern working life. Household surveys have provided evidence for the nonmaterial rewards of work in the more modern economies, and their respondents often say that they look for kinds of compensation beyond the material reward of the paycheck.

The question here is whether, as this book has been arguing, the relatively modern-capitalist economies are more rewarding in nonmaterial terms than the relatively corporatist or socialist economies. To approach that directly would require neatly decomposing each country—“this one 1 part modern capitalism, 3 parts corporatism,” “that one 2 parts modern capitalism, 1 part socialism,” and so forth. That would be highly subjective. Our approach will necessarily be indirect. Some features found in economies are thought to be most pronounced or more common in corporatist (or socialist) economies, other features most pronounced in modern-capitalist economies. We will investigate some signature features of corporatist, socialist, and modern-capitalist economies to see whether they are conducive or inimical to nonmaterial rewards—features such as corporatism’s high “employment protection,” extensive welfarism, short regulation work week, and collective bargaining; socialism’s gigantic public sectors; the bureaucratic “red tape” found in both of the latter systems; and capitalism’s individual freedoms. Not knowing exactly how to measure the degree of, say, modern capitalism in each country, we use data measuring the size of the “modern” organs—the organs understood to function in the generation of dynamism and thus inclusion—to see how they correlate with nonmaterial rewards.

Yet, as important as institutions and policies may be, we must recognize that every economy is a culture or mix of cultures, not just policies, laws, and institutions. The economic culture of a nation consists of prevailing attitudes, norms, and assumptions about business, work, and other aspects of the economy. These cultural forces may affect the generation of nonmaterial rewards indirectly through their influence on the evolution of institutions and policies, but also very directly through their impact on participants’ motives and expectations. An economy may owe its vibrancy—its readiness to apply newly discovered technologies and adopt newly proven products—to one or more components of its economic culture; an economy may owe its dynamism—its success at using the creativity of people to achieve indigenous innovation—to some other components in its cultural repertoire. A political culture may also suit a nation for innovation under some conditions, at any rate. To the extent that cultural differences are important, inter-country differences in nonmaterial rewards are to be explained not by crude labels—modern capitalism, corporatism, and socialism—and not only by the size and settings of a few institutions or policies, each characteristic of one kind of system or another, but also by measurements of some elements in the culture, each thought to be a key force in modern capitalism or corporatism or socialism.

In the economics that has been standard from David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill to the present day, the concept of a culture does not come up, as if there were just one culture in Western civilization—despite the dissents of Thorstein Veblen and Max Weber. Outside standard economics, however, anthropologists recognized that not all societies’ cultures are alike and the differences matter. Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that every society’s culture deserved respect, having arisen to meet its own special needs, and Ruth Benedict maintained that some societies had cultures that were not the best for them. The psychiatrist Erich Fromm said that some cultures were extremely bad, arguing that fascism took over where the culture did not value individual freedom.

In the past decade, though, culture has been making its way into economics. It is increasingly hypothesized that culture is the glue or “missing link” that loosely ties a country’s economic performance in the present to that in even the distant past. “The apple does not fall far from the tree,” good tree or bad.1 Many observers have remarked at how effortlessly some countries, after being down and out, climbed back to a high place in the league tables: most European countries climbed back more or less to the position they had before their interwar traumas.2 However, there can be no doubt that new experience and new ideas can change a country’s culture. Nazi opposition in the 1930s to women working had a long-lasting effect, but over the past decade Germany’s female participation rate has rebounded. Margaret Thatcher’s campaign in the 1980s to sweep away British companies’ aversion to competition has left a mark in the view of most observers, but there are now calls in Britain to return to “industrial policy.” Historians of China are suggesting that China’s economic reformation in 1978 under Deng Xiaoping succeeded thanks to a deeply seated culture that could be traced back to 1500. The West’s modern era brought new thinking and, to varying degrees, new ways of behaving, as this book has argued at several places.

Disparities in Job Satisfaction

It is widely assumed that the “economically advanced” countries do not differ significantly in their nonmaterial rewards. Since they are about equally productive, the reasoning is, they must produce things the same way, and so the work experience must be the same too. (Standard economics supposes that the robotized economies of their theoretical models have no culture.) But that is a profound and serious misconception.

In fact, there are striking differences in job satisfaction within the West. That became clear with the publication of a wave of survey data gathered in 1991–1993 for World Values Surveys (WVS)—a mine of data on individuals’ satisfactions as well as “values,” that is, attitudes, norms, and beliefs. The bar chart in Figure 8.1 gives graphic evidence of differing levels of mean job satisfaction among Western countries.

FIGURE 8.1 Mean job satisfaction, 1990–1991. (Source: World Values Surveys.)

Understandably, doubts are raised. Is job satisfaction another term for wages or wealth? Empirically, ranking high in national wealth and wages is not a predictor of a high rank in job satisfaction. David Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald comment that job satisfaction was very high in one of the poorest countries in their 1990s sample, Ireland, and low in Mediterranean nations. It may be wondered whether the disparities in job satisfaction are merely transitory differences. Happily, the 1999–2000 job satisfaction data gathered by WVS in its subsequent survey, which unaccountably omitted the United States, do not rank the countries much differently from the first survey, as Figure 8.2 shows.

It is sometimes asked why it is useful to study job satisfaction. Why not go directly to the overall measure called life satisfaction? The answer is that we come to understand better what determines life satisfaction by studying job satisfaction on the way. It would be neglectful to study life satisfaction without studying the components: satisfaction with jobs, with family, and with economic situation (“financial satisfaction”). When we can study the sort of satisfaction that is specific to jobs and the effects that economic institutions and cultures have on it, we should prefer to start there for the sake of clarity.

FIGURE 8.2 Mean job satisfaction, 1990–1991 (black) and 1999–2000 (gray). (Source: World Values Surveys.)

One issue is urgent, however. Conventional opinion holds that if a society’s economy is geared to create jobs that offer significant challenge and reward, it pays a steep price in the form of reduced family satisfaction: harried couples and neglected kids. That traditionalist perspective views it as an open question whether a modern economy makes a net positive contribution to life satisfaction. Observation is all on the side of the modernist perspective, however. Children clearly benefit from parents engaged in their jobs and having interesting things to talk about at the dinner table. So while intensive involvement in work and career detracts from the time available for the family, it has benefits for the value of the family time that remains. In a survey a decade ago, kids expressly said that they wanted their parents not to sacrifice more of their careers for the sake of children but rather to solve their problems and get on with their lives.3 The WVS adds its support for the modernist view. Its data show that the countries lowest in job satisfaction are lowest in family satisfaction, and the ones highest in job satisfaction rank—such as Denmark, Canada, America, and Ireland—are high in family satisfaction. All of this telegraphs the punch line in Figure 8.3: life satisfaction is positively correlated with job satisfaction and strongly so. Case closed.4

FIGURE 8.3 Mean job satisfaction, 1990–1991 (black) and mean life satisfaction, 1990–1991 (white). (Source: World Values Surveys.)

The waves of data on reported job satisfaction that have washed up in recent decades have led to misuses and misinterpretation. Some observers, pointing to Sweden’s high score in job satisfaction, take this to be evidence that the Swedish economic system—a unique mixture of capitalism and welfarism with little dynamism—is the “best system.” Others, pointing out that Denmark scored even higher, conclude that the Danish system—with its Flexicurity or some other attraction—is the best. That way of using the data is absurd. It is a schoolboy error in Statistics 101 to draw inferences from “outliers” rather than from the data as a whole. “Well, yes,” one might say, “but it is fair to conclude that the United States does not have one of the best systems!” That too is a methodological error. A country’s finishing on top in some test may be the effect of some purely temporary boost either from an extraneous force or from an unsustainable improvement of its system. When the best tennis player is put up against many contenders, one of them may win the tournament, but we know enough not to infer the winner is the best player. If there are many contenders, the best player may have only a small chance of being the winner. In fact, after all the hoopla over Denmark, the 2002 International Social Survey Programme delivered a sharp downgrade to Denmark’s job satisfaction. The second wave of WVS data, from 2000 to 2002, shows a similar drop in Sweden.5

A common misinterpretation is to suppose that reported job satisfaction mainly reflects the job’s pay, not the nonpecuniary satisfactions that household surveys were intended to measure. First, if wages among the countries in the West differ little, we cannot attribute differences in reported job satisfaction to differences in wages. Second, if pay were the main source of reported job satisfaction, one would wonder why the United Kingdom, with very low wages relative to their wealth, reports a pretty decent level of job satisfaction and why Germany, with its fairly high wages relative to wealth, reports a middling level of job satisfaction—like Italy and Austria. Third, what slender association there is between high reported job satisfaction and high income is significantly explained by the tendency of high-income job holders to have attitudes and beliefs conducive to high nonpecuniary satisfactions.

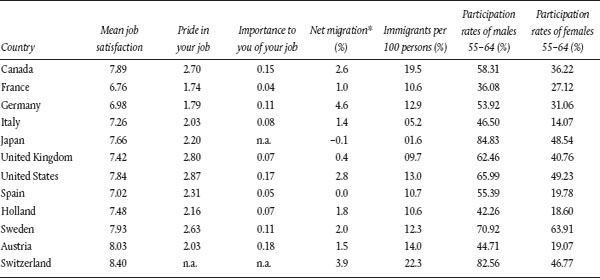

The plausibility of the reported job satisfaction levels receives a big boost from the reported satisfactions from work of particular kinds—pride in one’s work and the importance to one of one’s job. See Table 8.1. The rankings of countries by these two reported satisfactions, Pride and Importance, are very similar to their ranking by reported job satisfaction. Among the G7, one of the top countries in mean job satisfaction, the United States, scored highest in both Pride and Importance. (It scored above Sweden and tied Denmark in these respects.) The country at the bottom in mean job satisfaction, France, was at the bottom in Pride and Importance. (Perhaps the importance that the Scandinavians place on their jobs, the pride they take in them, and even their job satisfaction owe more to the Lutheran attitude of seriousness and the Calvinist significance of work than to a humanist delight in challenge and testing one’s ingenuity and one’s vision.) So it appears likely that the scores on job satisfaction are based on respondents’ consideration of various nonpecuniary, or nonmaterial, rewards from work.

TABLE 8.1 Indicators of Mean Nonmaterial Reward in the G10 + 2

Sources: Data are from Inglehart et al., Human Beliefs and Values (1997); Stock of Immigrants per Person (2005); United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report on Mobility (2009).

Notes: Job satisfaction responses are numbers between 1 and 10 (c033 in the World Values Surveys codes). Responses to “Do you take pride in your job?” (c031) are between 1 and 3. Responses to “Is your job the most important thing in your life?” (c046) are between 0 and 1. The table shows the mean of the responses. These data are from the wave of surveys taken during 1990–1993. n.a., not available.

*Net migration is for 1981–1990 as a percentage of the 1981 population.

A contrarian interpretation argues that a country’s low score on reported job satisfaction may be more about how demanding the respondents are than how unstimulating their jobs are. They may suffer low job satisfaction because, as in Italy and France, they are spoiled by their wealth. But America and Canada did not lack for wealth, especially in 2001, coming after the dot.com boom, and they have continued to rank high in job satisfaction. And Figure 8.2 reminds us that when Ireland went from poor to rich in a decade, it remained near the top in job satisfaction. Furthermore, if high levels of reported high job satisfaction are not genuine, one would be left with no explanation of why foreign populations flock to the countries with the highest reported levels—namely, Canada, the United States, and Sweden plus Germany. (Immigration into Germany may be laid in part to its proximity to the outflows of people from Eastern Europe.)

Institutional Causes of the Disparities

Comparative studies in recent decades of various dimensions of economic performance in the economies of Western continental Europe have implicitly assumed that the basic economic system in these nations—a corporatist system that lets big business, big labor, and big government (plus any smaller special interests that can win influence) have a veto over market outcomes—were about as effective as the modern-capitalist system in meeting a variety of goals. What the authors argued was that the European countries tripped up by injecting one or more impediments and hindrances in the market, apparently on the belief that their cost was negligible or modest enough to be worth paying. Some economists hypothesized that EPL helped explain the relatively low economic performance found in several of the 18–22 advanced economies of the West.6 Some others hypothesized that the high unemployment insurance benefits financed by a payroll tax that are pronounced in some of these countries led to their inferior performance.7 Other studies suggested that the combination of big unions and big industrial confederations bargaining over wages (and many other things) is significantly damaging.8 The rate of the value-added tax and the average tax rate on labor income were also suspect—either as a measure of after-tax wage reduction or a measure of the scale of the social insurance benefits that the “social charges” on wages were paying for.9 Also suspected were the short work week or work year,10 so beloved on the Continent, and the protectionist interferences with imports.11 A clever hypothesis was that the drag on the Continental countries was not the corporatism of their economies but the Roman law they stayed with in preference to the Common Law in the Anglo-Saxon countries.12 The trouble is there is no end to such hypotheses, and many of the supportive findings would likely be spurious—correlations that are just happenstance, not causal. Our interest is in differences in economic dynamism between corporatist and modern-capitalist economies and any resulting effects on job satisfaction, which EPL, unemployment insurance benefits, and value-added tax might have little to do with in the larger scheme of things.

It is a theme of this book that the Continental countries in adopting EPL and the rest were not starting with a system as good as (or better than) the relatively modern-capitalist economies. Differences in the deep institutional structure as well as deep differences in economic culture between the relatively corporatist and the modern-capitalist economies are mainly responsible for the disparity in their dynamism and thus in their job satisfaction: corporatist economies underperform in job satisfaction mainly because they fail to develop fully modern-capitalist institutions and a modern culture that meet the requirements for high economic dynamism. That contrasts sharply with the view, implicit in most economic investigations, that some countries, which happen to be corporatist, in injecting EPL, unemployment insurance benefits, high value-added tax, and the rest, threw a monkey wrench into the works of their otherwise perfectly fine economic systems. This latter view, pronounced by academic economists from Chicago to MIT, is a tenet of neo-liberalism, which holds that a country has only to prohibit governments and market actors alike from overturning competitive, or free-market, prices and wages, to have successful economic performance. It is conceivable and maybe plausible that the elimination and avoidance of interferences with competition would be sufficient for satisfactory performance, as a line of economists descending from Adam Smith maintained with qualifications, in an age when performance—even the best-possible performance—was only a matter of productivity and jobs. But in the modern era, those neo-liberal institutions are insufficient. Ever since the modern era finally began planting the ideas that blossomed into the first modern economies—economies with a demonstrated aptitude and capacity for indigenous innovation—a country cannot have high economic performance without high economic dynamism. And it cannot have much dynamism without institutions and an economic culture that potentiate conceivers of new commercial ideas, facilitate entrepreneurs to develop these new ideas, allow employees to contract to work long and hard, and protect against fraud financiers willing to invest in or lend to enterprises and consumers (or other end-users) willing to try products found in the market. Many of the institutions performing those functions—a virtual infrastructure of legal rights and procedures—arose in the formation of commercial capitalism over the 17th and 18th centuries, but they helped to support innovation as well.

In this thesis, the modern capitalism arriving here and there in the 19th century boasted new institutions aimed expressly at potentiating or facilitating innovation, such as a well-designed system for patents and copyrights, and some other institutions aimed at encouraging participants to bear the heightened uncertainty that attends ventures into the unknown, such as limited liability, protection of creditors and owners in the event a company fails, and protection of the manager against shareowner suits. Similarly, some elements of modern economies’ economic culture originated in earlier eras, such as the notion of the good life originating in ancient Greece, while modern morals germinated only at the dawning of Barzun’s “modern era.” That is the theory. Does it to a degree explain differences in job satisfaction? Differences in dynamism?

A wide-ranging study in 2012 by Gylfi Zoega and the present author explores the parts played by capitalist institutions in determining mean job satisfaction in the OECD countries studied.13 Note first of all that countries differ in the strength and breadth of several categories of institutions. Some legal institutions of the capitalist type appear to be strongly developed in Ireland, Canada, Britain, and America and weakly developed in the others. For example, the Fraser Institute since the mid-1990s has been ranking a large number of countries by their score in a category labeled Legal Structure and Security of Property Rights. (A country’s score is the value of an index, or average, of the numerical measures of its institutions under that category.) In 1995, Ireland and Canada ranked 8th and 11th, respectively, and the United Kingdom and the United States were 14th and 15th. On the low side were Belgium in 24th place, France 25th, Spain 26th, and Italy 108th. The highest-ranking nations tended to be northern: Finland 1st, Norway 2nd, Germany 5th, and Holland 6th.14 But property rights are just one institution that may help account for differences in job satisfaction.

Three categories of financial institutions are at the core of capitalism. One is represented by the capital access index, which is compiled by the Milken Institute from its measures of the “breadth, depth, and vitality of capital markets.” Another is the number of companies choosing to list their shares for public trading on an organized stock exchange, expressed as a percentage of the number of firms in the economy. The third is the market value of the shares traded on the exchange, called stock market capitalization, expressed as a percentage of the GDP. The worth of these institutions for innovation might be questioned in view of the problems with so-called corporate governance in recent years. (The next chapter sets out some serious defects of the present-day system.) However, even a highly imperfect institution, if it helps both new and established firms to obtain capital through an initial public offering or a flotation of additional stock, may well be superior to a system without public capital markets. New companies, being small at first, have some key advantages in developing radical new ideas; while ever-small companies, generally family owned, that are able to hang on by reinvesting their profits or by borrowing and then seeking bankruptcy protection are holding on to resources that could have been used in innovative enterprises. So what do the data show? The statistical study in the aforementioned working paper by Phelps and Zoega finds that underdevelopment (or atrophy) in these two time-honored capitalist institutions—access to capital and public stock exchanges—help explain deficiencies in job satisfaction. A society benefits from a Jeffersonian freedom to start small companies, but it also benefits from institutions enabling them to grow to larger ones.

Are differences in the spread or well-functioning of modern institutions, such as those at the birth of modern capitalism, not also significant in accounting for differences in job satisfaction? Yes, of course, though the measurement of many of those institutions—the measure of a well-designed patent law, for example—is somewhat challenging. Since generally speaking, radically new ideas are best developed in new firms, the dismantling of feudal and mercantile barriers to the entry of new firms and the formation of new industries, which America accomplished when it gained independence from the tight rein of King George III, is one of the key institutional steps for the functioning of modern capitalism. In concept, then, institutions that remove red tape, if we had measures of such institutions, would help to explain high job satisfaction in modern-capitalist economies. But the granularity and idiosyncratic nature of many institutions in this area make it hard to represent them with numerical measures. So a couple of telling anecdotes might not be out of place: the founder of eBay, the Frenchman Pierre Omidyar, told an audience at Aix-en-Provence in 2005 that he would not have been able to found eBay in France, but he did not articulate why; perhaps he could not easily do it. Another prominent entrepreneur told Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron recently that he could not have started his business there owing to Britain’s lack of some key institutions.

An institution that is basic to the operation of modern capitalism is company law: bankruptcy protection of companies from creditors, protection of companies from self-dealing by managers, protection of companies from employees who do not perform, limits on what companies may ask employees to do, and so forth—a concept articulated to a degree by Heritage under the rubric of business freedom. Under the proto-capitalism of pre-modern times, a landowner might contract labor to harvest the crop. Under modern capitalism, companies and individuals come together, each party investing time or money in the relationship, without being able to foresee the tasks, some of them emergencies, which may arise in the future. It is impossible for an employee and employer to write a contract that would take account of all possible contingencies. Law is needed to set limits on the resolution of conflicts when the contract does not cover the state that the company is in. Without such legal support, an entrepreneur or an investor might hesitate to embark on the creation of an untried product if it would be problematic to hire or fire as necessitated by unforeseeable developments, or to replace an ineffective manager with a better one. Creation does not always cause destruction, but destruction-prevention makes it harder to obtain resources for creation.

Finally, the economic policy in a country is an institution that may significantly induce or thwart entrepreneurship aimed at innovation. Relying on scant data and an overly specific theory, Conservatives leap to the conclusion that every element of economic policy providing a role for the government has a cost exceeding the benefit—with few exceptions. But while there may have been a presumption that this or that intervention by the state in the activities of the business sector—more corn or less cloth—would be harmful in the pastoral economies of mercantile capitalism, there is no presumption that, say, more money for education or less money for education would disturb innovation from its optimum equilibrium—or disturb innovation at all. We do not know whether this or that concrete governmental activity would be constructive or detrimental for the dynamism of the economy and thus for job satisfaction. Yet research on such a question is often possible and may turn up results that force rethinking. For example, the evidence of the working paper cited above does not corroborate the supposition that subsidies to low-income workers, such as America’s Earned Income Tax Credits, intended to draw the disadvantaged into employment and greater self-support reduce job satisfaction. It could be that integrating marginalized people into the business world has served to enlist the creativity of a whole section of society whose talents would not otherwise have had an outlet.

The welfare state offers another example. The same working paper by Phelps and Zoega finds that countries with high levels of state spending for social insurance, that is, medical care, and retirement benefits, let alone education, do not tend to have depressed levels of job satisfaction, though that finding may be driven by the data from some very peculiar nations, such as Norway, with its oil, and Austria, with its waltzes.15 Jean-Baptiste Say, the great French economist of the late 18th and early 19th century, identified a problem with big government in his 1803 treatise Traité d’économie politique. To paraphrase Say:

Where the government’s purchases are spread thick over the whole economy, the thoughts of entrepreneurs, which would have been occupied with a better method or a better product that caused incomes to grow, inevitably turn to how to exercise influence in order to beat out competitors for the government’s new contract. So a high level of government consumption costs an economy some of its dynamism and thus, in turn, some job satisfaction.

In contrast, the working paper does not find that all that corporatist intervention for the “protection” of employees and industries raises job satisfaction either. The corporatist belief that core elements of human fulfillment would be lifted by making people more secure appears to be an illusion.

Regulatory institutions appear to be a significant depressant on job satisfaction, particularly credit market regulations (such as interest rate controls) and goods market regulations. The institutions of collective bargaining and regulations on hiring and firing are also estimated to depress mean job satisfaction. Some corporatist institutions, such as a willingness to run large export surpluses to finance interest and dividend payments to foreign creditors and investors, may have helped these nations attract foreign investment and transfer foreign technologies and foreign capital. However, if the evidence does not mislead, corporatist institutions nevertheless led to reduced job satisfaction.

Cultural Causes of the Disparities

An economy, it will be recalled, consists of an economic culture as well as a set of institutions; and that is especially true of a modern economy. (Schumpeter says in his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy that a capitalist economy is essentially a culture, but he meant that it develops habits and standards.) The hypothesis here is that a basic element of the culture, namely prevailing attitudes and beliefs, has consequences for one’s efforts at work and for the effectiveness with which one can collaborate with others; in both ways, one’s job satisfaction is affected. These attitudes and beliefs are often called values. (The economic culture also includes attitudes such as those developed in companies, so that we often speak of the company culture at outstanding firms like Google.)

What values spark economies capable of offering high satisfaction with economic life? We will draw on the data gathered on attitudes, norms, and beliefs by anthropologists, ethnologists, and sociologists to see whether inter-country differences in the prevalence or intensity of these cultural values help account for inter-country differences in job satisfaction. (The analysis leaves aside the question of whether the influence of values held by employees, managers, and customers on satisfaction are indirect, in that they lead to a change of institutions, or direct, in that no change in institutions results unless the institutions adjust accordingly.)

The mention of economic culture brings immediately to the mind of many social scientists the characteristic called trust. It would seem that, very generally, a society works better if people are brought up to be law-abiding and respectful. The idea burst forth around 1970 with The Gift Relationship by the sociologist Richard Titmuss and, slightly later, The Possibility of Altruism by the philosopher Thomas Nagel. The issues were aired in a conference and ensuing volume organized by the present author.16 But trust is left aside in the argument at hand for two reasons. One is that it might seem rather confusing to mix altruism with culture for the same reason that we keep morality separate from ethics. (Morality is about what ought to be done universally for the common good—such as, be altruistic—and ethics is about what an individual person is wise to do for her own good.) The recent literature on the effects of economic culture appears to have put altruism aside. The more powerful reason trust is omitted here is that there is no clear presumption that economic dynamism would be helped (or would be hindered) by more altruism, and, even if there were, there is no strong presumption that altruism is the preserve of modern-capitalist nations and not corporatist ones (or vice versa). So altruism is best left aside in this study.

The French businessman Philippe Bourguignon, whose working life has been divided about evenly between America and Europe, has portrayed the two regions as having quite distinct cultures.17 In his analysis, the differences originate in the very different upbringings of children. French mothers, he observed, watch their children closely in the playground; they are attentive and warn them to be careful. American mothers, on the other hand, pay little attention and do not teach caution. As a result, Americans grow up taking failures in stride and moving on, so they are relatively undaunted by high rates of failure.

Another observer found a deep divide between the vocabulary of values on which business life is viewed in continental Western Europe and the normative concepts deployed in America, Canada, Britain, and Ireland. Investigative reporting by the journalist Stefan Theil found that France and Germany view private enterprise and market outcomes through radically different ethical lenses:

The three-volume history book used in French high schools, Histoire du XXe siècle, … describes capitalism at various points in the text as “brutal” and “savage.” “Start-ups,” it tells its students, are “audacious enterprises” with “ill-defined prospects.” German high schools … teach a similar narrative with the focus on instilling the corporatist and collectivist traditions. Nearly all teach through the lens of workplace conflict between … capital and labor, employer and employee, boss and worker.… Bosses and company owners show up in caricatures and illustrations as idle, cigar-smoking plutocrats, sometimes linked to child labor, Internet fraud, cell-phone addiction, alcoholism and undeserved layoffs. One might expect Europeans to view the world through a slightly left-of-center, social-democratic lens. The surprise is the intensity and depth of the bias being taught in Europe’s schools.18

Theil’s investigation suggests that the lenses through which people look at their world are quite different from country to country—more different than the worlds being viewed are. It also suggests that such differences result from some marked differences in the values that people have or in the way they rank some shared values, such as safety and security, invoked by Bourguignon.

The WVS, which this book has drawn on previously, produce large sets of survey data on values around the world. These surveys show that the prevalence of almost every value—precept or attitude or worldview—differs considerably from country to country. Statistical analysis of the individual responses to questions about values shows that little of the inter-country differences can be ascribed to the chance variations that result from the random sampling of individuals possessing a degree of uniqueness; the inter-differences far exceed what might be forecast from the observed differences. As could be expected, some values in these surveys are markedly stronger in the relatively modern-capitalist economies than in the corporatist economies, some other values markedly stronger in the corporatist countries.

It is a central proposition of this book’s thesis that several values play a part in a country’s generation of high economic performance—a proposition that, up to now, has been a hypothesis in search of confirmation. Some of these values affect the capacity and desire to conceive novel ideas, to develop these ideas into new products, and to try out the new products. Other values may affect economic conditions that support or damage the commercial prospects for innovation. In these ways, many values in the West—whether associated with modern capitalism or with corporatism—can be presumed to affect job satisfaction. They could affect job satisfaction through their direct effects on the stimuli and challenges of the workplace or through indirect effects by opening possibilities for new institutions that served to make the economy more challenging and rewarding. The moment has come to confront this hypothesis with the available survey data.

A research program at Columbia’s Center on Capitalism and Society has been testing the influence on economic performance—ultimately, the effect on job satisfaction—of the West’s culture of problem-solving, curiosity, experiment, exploration, and novelty and change. The first results were announced in a paper given at the 2006 conference in Venice on what ails the Continental economies.19 The paper injected the values of the economic culture into the discourse. It selected nine workplace attitudes from WVS to study their possible effects on economic performance. Several of these values were significantly associated with high economic performance in one or more dimensions. How the survey respondents in a country valued the “interestingness of a job” (c020 in the WVS classification) was significantly related to how well the country scored in several dimensions of economic performance. The acceptance of new ideas (e046) was also a good predictor of performance. The desire to have some initiative (c016) was also a good sign. A low willingness to follow (c061)—to take orders, which is conspicuous in some European nations—exacts a significant toll on a country’s economic performance. A readiness to accept change (e047) and a willingness to accept competition (e039) are quite helpful. A desire to achieve (c018) matters little: it is the experience—the life—that people want, not some object.

It appears that the hypothesized influence of the various cultural elements is borne out rather generally. It appears also that the WVS values that are so successful are modern-capitalist values; they are values in which the countries suspected of being corporatist—France, Italy, Holland, Belgium, and so forth—are lacking relative to the usual comparators—America, Canada, and Britain—and small seafaring nations, such as Denmark, Ireland, and Iceland. But the paper did not test for effects on the performance indicator that is the focus of the present chapter: job satisfaction. It would be feasible to return to those data to check that the attitudes found to affect significantly the time-honored measures of economic performance—labor force participation, relative productivity, and unemployment—also significantly affect job satisfaction. There is no doubt about the results, though. And a more structured approach is more interesting.

The history told in this book suggests another way to test the importance of economic culture for job satisfaction (and, more widely, for economic satisfaction in general). The history speaks of the modern ethic—a desire for self-expression through the exercise of imagination and creativity—and the modern morality—the right of individuals to pursue this search unchained from traditionalism: obligations to family, community, country, and religion. The history of the world, Part Two, is all about this seesaw battle between modernism and traditionalism—the great, endless struggle in the West from the early 1800s to the present. Where modernism gained the upper hand, traditionalism losing ground, a modern economy developed and society flowered, as in Britain and America. Although France, with its fraternity and equality, differed somewhat, as did Germany, where traditionalism (and socialism) remained a force, these nations also fashioned relatively modern economies. But with the revivals of traditionalism over much of Europe in the 1900s, national economies there drew back from the modern end of the spectrum.

If that is a fair history, we should expect to find a more impressive flowering and very likely a wider one, thus a higher level of mean job satisfaction, in a society where the cultural values of modernism are strong. And although elements of traditionalism might have their uses, we should not be surprised if job satisfaction is also higher where the values of traditionalism are weak.

A 2012 working paper by Raicho Bojilov and the present author tests whether modernist values in a country contribute to mean job satisfaction. It measures in each nation under study the attachment to some values found in the WVS that are a sign of a modernist culture or a lack of it.20 The measures were calculated from the responses to the following yes-or-no questions: Do you think that it is fair to pay more to the more productive workers? (c059). Do you think that the management of firms should be under the control of their owners? (c060). Do you agree that competition is good? (e039). It also asks questions that call for a response on a scale from 1 to 10: Should one be cautious about major changes in life? (e045). Are you worried about new ideas? Do you believe ideas that have stood the test of time are generally better or may new ideas be worth developing and testing? (e046). Do you worry about difficulties that change may present or do you welcome whatever possibilities something new may present? (e047). By quantifying the responses in a country to these questions, we calculate the mean strength of that value in the country. By taking an average of these six quantitative measures, we obtain an index of modernism.

An index of traditionalism is constructed in a somewhat similar way. Survey questions were selected that would presumably pick up a strong concern for obligations to family and community, a concern strong enough that economic developments that would draw children away from the family or the community would not be well received. Some traditional values are captured by four of the WVS questions: Do you feel that service to others is important in life? (a007). Do you think that children should have respect and love for their parents? (a025). Do you think that parents have responsibilities to their children? (a026). Do you agree that unselfishness is an important quality for your children to have? (a041). It is not being suggested here that it’s a terrific aid to innovation to have economic actors who are monsters toward their parents or neighbors, only that innovation could be suffocated by a fixation on family and community to the exclusion of the individual.

FIGURE 8.4 Traditionalism and job satisfaction, 1991.

What are the results? It might be thought that the traditional values are a precious glue holding society together and thus indirectly raising job satisfaction and other rewards from participation in the economy. It might also be thought that a little bit of modernism goes a long way; that important amounts of modernism weaken coordination, causing angst and a loss of the deep job satisfaction known to craftsmen in olden times. Continental politicians pay tribute to these cherished beliefs in every speech. The findings from the study, however, strongly suggest that neither one of these prejudices is true.

The results are shown in graphic terms in Figures 8.4 and 8.5, which draw on the indexes of modernism and traditionalism tabulated in Table 8.2. In the first of these figures, traditionalism appears to be an impediment to high job satisfaction. There are three countries, Finland, Denmark, and America, that score conspicuously low in traditionalism and quite high in mean job satisfaction—countries often cited for their high dynamism too. And there are three countries, Portugal, Spain, and France, that score conspicuously high in traditionalism and very low in mean job satisfaction. Furthermore, the (negative) statistical correlation in the sample as a whole is highly significant. Sweden, Canada, Ireland, and Denmark have higher satisfaction than their modest or low traditionalism explains, but they have something that most of the others do not—as the next figure shows.

FIGURE 8.5 Modernism and job satisfaction, 1991.

Figure 8.5 shows that modernism gives a strong boost to the level of job satisfaction. The countries scoring high on modernism scored high on job satisfaction. The nations with the most modern cultures—Iceland, Finland, Sweden, Canada, and America—did very well in job satisfaction. (In 2001, though, Sweden’s job satisfaction fell considerably.)

The two figures together show that Italy’s mediocre satisfaction is well explained by its high traditionalism, which its above-average modernism could not offset. France’s low satisfaction is explained by the above-average traditionalism and below-average modernism. Germany’s depressed workers and Austria’s delighted ones are a puzzle. Evidently, values are not everything.

TABLE 8.2 Indexes of Modernism and Traditionalism

|

Country/region |

Index of modernism |

Index of traditionalism |

|

Austria |

0.55 |

0.49 |

|

Belgium |

0.50 |

0.49 |

|

Canada |

0.61 |

0.50 |

|

Denmark |

0.58 |

0.44 |

|

Finland |

0.62 |

0.38 |

|

France |

0.49 |

0.59 |

|

Germany |

0.58 |

0.45 |

|

Iceland |

0.63 |

0.54 |

|

Ireland |

0.54 |

0.59 |

|

Italy |

0.56 |

0.58 |

|

Japan |

0.42 |

0.48 |

|

Netherlands |

0.58 |

0.49 |

|

Norway |

0.53 |

0.44 |

|

Portugal |

0.50 |

0.71 |

|

Spain |

0.47 |

0.62 |

|

Sweden |

0.62 |

0.51 |

|

United Kingdom |

0.56 |

0.54 |

|

United States |

0.59 |

0.44 |

|

Average |

0.58 |

0.51 |

It may be surprising that so many countries ranked higher in modernism than America did in the last available measurement—the country that most embodied it in the 19th century and much of the 20th. Could something have happened over time? Significant changes in a country’s culture are rare in 10 years’ time, as we saw in Figure 8.2, but not so rare in the space of several decades. Whether the American economy has suffered a loss of dynamism in recent decades and whether, behind that, is a decline of modernism or a rise of traditionalism are questions for the next chapter.

1. This theory sees the culture as a slow-moving causal force that may ultimately trigger an abrupt change of institutions—as shifting tectonic plates finally provoke an earthquake. See Roland, “Understanding Institutional Change” (2004). (There the culture is another institution—the slow-moving one. This book breaks out culture from institutions.) The hypothesis here allows new ideas to drive institutions and possibly culture too. Things would change even if culture never did.

2. A Spanish economist, chatting with me at a 1993 meeting in London, observed that in the early 1920s Spain’s GDP per person put it in 8th place in the league tables, Western division—trailing America, Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, Britain, and Italy. After all that Spain had been through since then, from the Spanish civil war to Franco’s reign and the post-Franco decades, Spain was again in 8th place.

3. One authority setting out the family tensions thesis is Anne Marie Slaughter. Lucy Kellaway, with evident relish, set out in the Financial Times the counter-thesis.

4. The tight relationship between job satisfaction and life satisfaction, also known as total satisfaction, is shown in Bojilov and Phelps, “Job Satisfaction” (2012). In a paper given at a conference some five years earlier, Phelps and Zoega, “Entrepreneurship, Culture and Openness,” the authors treat life and job satisfaction as interchangeable.

5. A quite different problem is that, when we ask whether some causal force raises or lowers performance of economies on the whole, the effect in each small country—Finland, Sweden, Luxemburg, Denmark, and Iceland—receives the same weight given to the effect in the entire United States. It might be better to start with a sample in which California, Oregon, Massachusetts, Illinois, and other U.S. states receive the same weight as each of the European countries.

6. Lazear, Elmeskov, and Nickell are among the leading investigators into the matter. An interesting paper by Bentolila and Bertola, “Firing Costs and Labour Demand,” built a hypothetical model of the representative firm in which theoretically the adverse impact of EPL on the rate of hiring is more than offset by the negative effect on the rate of firing, which pointed to the conclusion that, on balance, EPL reduces unemployment. That analysis, however, overlooked a “systems effect”—that the insiders, entrenched by the job protection, drive employers to raise wages and thus trim jobs throughout the economy.

7. Jackman et al. (1991); Phelps and Zoega (2004).

8. See for example the 2001 paper by Nickell, and the 2004 paper by Phelps and Zoega titled “The Search for Routes to Better Economic Performance in Continental Europe: The European Labour Markets.” Lars Calmfors argues that the ill-effect of this bargaining, organized in the corporatist way, disappears if a single union represents all the economy’s workers, for in that case the union will see any wage increase as costing more jobs than it would if it knew the industry could raise its price relative to other industries so as to pass along the cost increase.

9. Phelps and Zoega (2004).

10. Phelps, “Economic Culture and Economic Performance.”

11. Phelps and Zoega, “Entrepreneurship, Culture and Openness” (2009). After discussing job satisfaction as well as life satisfaction, the study focused on life satisfaction.

12. Balas et al. “The Divergence of Legal Procedures.”

13. Phelps and Zoega, “Job Satisfaction: The Effect of Modern-Capitalist and Corporatist Institutions.”

14. These data are in Gwartney et al., Economic Freedom of the World (country data tables). Another Fraser category bearing on innovation is Freedom to Trade Internationally. (Clearly it is a boost to dynamism if aspiring innovators can expect adoption overseas, not just at home.) Here, Ireland ranked 4th, Britain 10th, America 18th, and Canada 31st, while Spain ranked 19th, Italy 24th, and France 32nd. Here, though, Belgium ranked 5th and Germany 9th. (The Nordics do not stand out here.) So the Continentals do not score badly at all in the institutions affecting foreign trade. But America is large enough to trade mostly with itself, so it suffers less from its failings in the free trade department than would a small country.

15. It is interesting and not hugely surprising that there is no such baleful effect of government investment expenditure. Perhaps capital projects, from the federal highways to NASA and NIH, raise the job satisfaction of the engineers, technicians, and scientists engaged in them—just as innovation and investment in the private sector lift the satisfaction of the people participating in them.

16. Phelps, Altruism, Morality and Economic Theory (1975). At a 1974 meeting of the Law and Economics Seminar at the University of Chicago I set out the reasoning behind the belief of those at the conference that a dose of altruism contributes to an economy’s efficiency. (I had not begun to think about economic dynamism at that time.) George Stigler, the lion of the seminar, demanded an example. I replied that people will be more willing to pay their full income tax if they are glad to make a small contribution to the work of the government or if they feel that other income earners will be paying their full tax too. Gary Becker, then a flaming neoclassical, said, “We’ll give you that one but can you give us one more?” I suggested that people would be afraid to venture out into the street or use a car if they were not confident that others want to obey the traffic laws in order not to do harm. Professor Stigler rejected that, arguing that people observe the traffic laws only to avoid their own inconvenience. Warming to his theme, he said, “People don’t want to have to stop to peel off the flesh on the windshield.”

17. Bourguignon, “Deux éducations, deux cultures.” The notion of “two cultures” will remind many readers of a famous lecture Two Cultures by C. P. Snow, who as a novelist and a scientist deplored that artists are ignorant of science and its remarkable culture. He could have added in the spirit of Bourguignon that the culture of scientists, like the culture of innovators, accepts failure: it is an integral part of the game. A game in which there was a certainty of success would be incredibly boring. It is true, though, that the scientific research and the entrepreneurial development we do tends to express who we are, so it hurts to fail.

18. Theil, “Europe’s Philosophy of Failure.”

19. Phelps, “Economic Culture and Economic Performance,” given at the Center’s 2006 conference and republished in the 2011 volume Perspectives on Performance of the Continental Economies.

20. Bojilov and Phelps, “Job Satisfaction: The Effects of Two Economic Cultures” (2012).