An Indian Border Security Force soldier stands guard at a gap in the border fencing between India and Bangladesh.

Like all walls it was ambiguous, two faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side you were on.

—Ursula K. Le Guin,

The Dispossessed

An Indian Border Security Force soldier stands guard at a gap in the border fencing between India and Bangladesh.

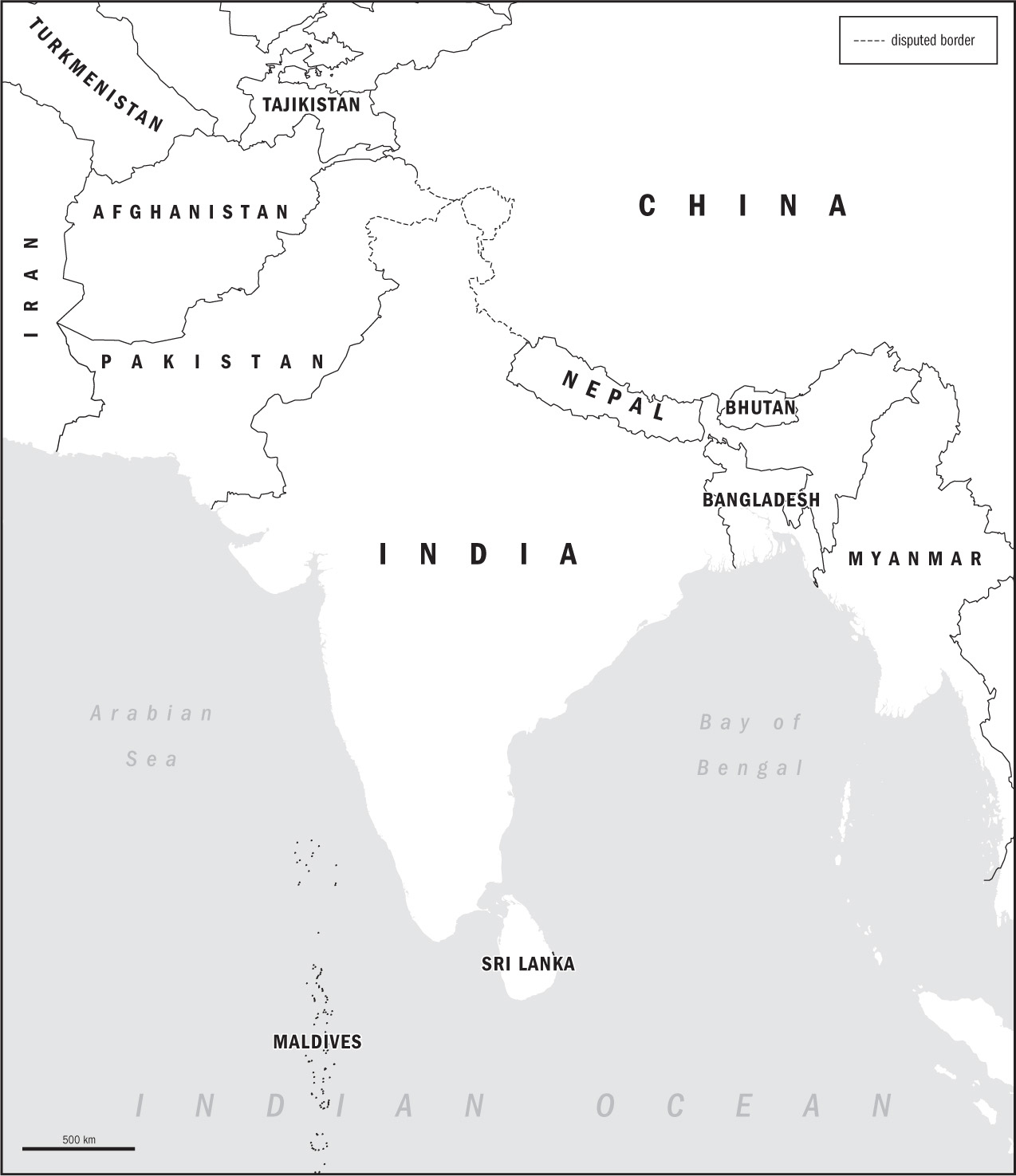

On India’s frontier with Bangladesh is the longest border fence in the world. It runs along most of the twenty-five-hundred-mile boundary that India wraps around its much smaller neighbor; the only part of Bangladesh completely free of it is its 360-mile-long coast at the Bay of Bengal. The fence zigzags from the bay northward, along mostly flattish ground, up toward the more hilly country near Nepal and Bhutan, takes a right turn along the top of the country, then drops down south again, often through heavily forested areas, back to the sea. It passes through plains and jungle, beside rivers and over hills. The territories on each side are heavily populated, and in many areas the ground is cultivated as close to the barrier as possible, which means the crops grown often touch the divide.

Hundreds of miles of this barrier are double layered, parts of it are barbed wire, parts are walled, parts electrified, and parts floodlit. In some stretches, West Bengal, for example, which comprises about half the border length, the fence is fitted with smart sensors, direction finders, thermal-imaging equipment, and night-vision cameras connected to a satellite-based signal command system.

The Indians are trying to move from a system that relied on large numbers of troops patrolling long stretches of border almost constantly to one that can easily pinpoint breaches in the fence and dispatch quick-reaction units. As with other frontiers around the world, technology has simplified what would previously have taken hundreds of man-hours to monitor, report, and act swiftly upon. Even if a sensor is tripped miles away from a control room, within a minute a drone can be overhead and a patrol on its way; the technology becomes more sophisticated each year.

Despite these measures, the Indian fence fails to stop people from trying to cross. They continue to do so despite the barbed wire, and despite border guards having shot dead hundreds of people attempting to get into India, and many others wanting to return to Bangladesh surreptitiously after being in India illegally. Among them, in 2011, was fifteen-year-old Felani Khatun.

Felani’s family had been working illegally in India without passports or visas, due to the legal complexity and costs of obtaining either. To return home for a family visit Felani and her father had paid a smuggler $50 to get them across. Just after dawn, with the border fence shrouded in mist, she began climbing a bamboo ladder placed against it by the smuggler. Her shalwar kameez snagged on the barbed wire. She panicked and began to shout to her father for help. Following a number of terrorist infiltrations, India’s Border Security Force (BSF) were under orders to shoot to kill, and a border guard followed orders. It was a slow death. She remained dangling on the fence, bleeding but still alive, for several hours. As the sun rose and the mist lifted, she could be seen and heard crying out for water before finally succumbing to her wounds. The shockingly violent, drawn-out death of such a young girl drew international attention and condemnation at the shoot-to-kill policy. Inevitably attention waned, but the politics remain, and so does the fence. Her death stands as testimony to the human cost of such barriers. India is not unique in this; there has been an increase in such deaths around the world. Dr. Reece Jones points out that “2016 set the record for border deaths (7,200 globally) because of the increase in border security.”

The fence on India’s border with Bangladesh is justified as preventing weapons- and contraband-smuggling and deterring cross-border insurgents; but primarily it’s there to prevent illegal immigration at levels that have resulted in riots and the mass killing of foreigners. Its main purpose is to keep people out. But in this turbulent region, migration is not the only issue. The divisions across the subcontinent, as we find so often around the world, stem partially from borders drawn by colonial powers, compounded by regional religious and ethnic prejudice and political realities. Many of the religious rifts can be traced back to Muslim rule over India in medieval times.

Following the first Islamic invasions from Central Asia, masses of the predominantly Hindu population converted; but the sheer size of India created problems for the invaders. As with China, it is almost impossible for an outside power to fully control India without building alliances. So although tens of millions of people converted to Islam, that still left hundreds of millions as Hindus. Even under the Mughal dynasty (1526–1857), when Muslim power expanded over almost all of India, the conquerors realized what the British would later discover: to take advantage of the subcontinent’s riches, it was easier to divide and rule the various regions than to seek absolute power. West of the Thar Desert and in the Ganges delta, a majority of people converted to Islam (the same regions that now compose Pakistan and Bangladesh), but almost everywhere else the majority of people remained Hindu.

In 1947, as the British withdrew, India’s founding fathers, especially Mahatma Gandhi, envisioned creating a multifaith democratic state stretching east to west from the Hindu Kush to the Rakhine Mountains, and north to south from the Himalayas to the Indian Ocean. But Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who would go on to become Pakistan’s first leader, believed that because Muslims would be a minority in this state, they required their own country. He wanted “a Muslim country for Muslims” and helped invent a border that was partially drawn along religious, not geographical, lines. The borders were drawn—by the British—to separate off areas that had a mainly Muslim population. So in 1947 two states came into being, India and Pakistan, the latter comprising West and East Pakistan. The religious divisions had become geographical ones, marked in the mind and on the landscape.

But often the border bisected existing communities, and all areas were mixed to some degree, so many people were compelled to move. The great division of the subcontinent in 1947 was accompanied by a wild bout of bloodletting. Millions were killed during the mass movement of peoples as Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims headed for regions where they would feel safe. Psychologically, none of the countries involved have ever recovered; the divides between them are as great as ever and are now increasingly manifested in concrete and barbed wire.

* * *

India is a magnet for migrants. It is a democracy, laws protect minorities, and compared to its neighbors, it has a thriving economy. Refugees and illegal immigrants have flocked there from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), Tibet, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. At least 110,000 Tibetans have fled since China annexed their territory in 1951, around 100,000 Tamil Sri Lankans arrived during their island’s civil war that ended earlier this century, and the upheavals in Afghanistan have led to a steady flow of people to India. But by far the greatest number of immigrants are from Bangladesh, which is surrounded by India on three sides.

Since the partition of India in 1947 waves of people from what was then East Pakistan have crossed into India to escape persecution, intolerance, and economic hardship, but the number increased following the violent conflict with West Pakistan. A glance at the map quickly shows why the two were never destined to remain a single country. They are thirteen hundred miles apart with different geographics and linguistics. After years of discrimination from West Pakistan, in 1971 the Bengalis in East Pakistan started agitating for independence. The Pakistani government ruthlessly attempted to suppress them, and in the ensuing violence, in which millions were killed, millions also fled to India. Today, many thousands are thought to cross the border every year.

In the mass migrations across the Indian subcontinent, people are fleeing poverty, the effects of climate change, and religious persecution.

Life is hard for many in Bangladesh. Around 12.9 percent of the population live below the national poverty line, as defined by the Asian Development Bank. Huge inroads have been made into the problem, but life remains extremely harsh for tens of millions of people. In rural areas the work consists of backbreaking farm labor, and in the growing cities massive slums house those arriving to find factory work. The minority groups, such as the Hindus and Christians, say they are persecuted, and overall, religious intolerance fueled by radical Islamists is growing. Reports of forced conversions of Hindus to Islam and of the kidnapping of young girls are numerous. The Bangladeshi constitution does not recognize minorities. Article 41 guarantees freedom of religion, but in practice the past few years have seen extremist groups attacking dozens of Hindu temples, burning hundreds of homes, and assaulting thousands of people. Many have fled toward Hindu-majority India. Add to this Bangladesh’s annual storms and flooding, and it is easy to see why so many people choose to cross the border.

For many people, however, it is not simply a case of migrating for work or fleeing persecution: the Indian-Bangladeshi border split communities that for centuries lived without physical divides. Some share linguistic and cultural similarities—the idea that their neighbor is of a different nationality is alien to them—and ever since partition they have continued to travel across the region.

Accurate figures are difficult to come by, but most estimates put the number of people who have moved permanently from Bangladesh to India this century at over 15 million. This has caused massive problems in the Indian states closest to the border—West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura—where the majority of (mostly Muslim) Bangladeshis have settled, but illegal Bangladeshi migrants are to be found in all the major cities of India. One of the most affected states is Assam, in the northeast of India. During the Bangladesh War of Independence the majority of people fleeing to India were Hindu, but soon increasingly large numbers of Muslims joined them. Between 1971 and 1991 the Muslim population in Assam increased by 77 percent, from 3.5 million to 6.3 million, prompting a major ethnic backlash against them, with locals complaining that not only was pressure being put on jobs and housing, but also that their identity and culture were being challenged. Some Hindus fell prey to blaming all ills on the newcomers no matter what their background because they were not Assamese, but Muslims suffered the most. What are essentially small differences, say, in the eating of pork or beef, became magnified as tensions rose.

In 1982 mass anti-Bangladeshi demonstrations began in Assam, leading to the formation of militias and eventually to rioting, in which thousands of non-Assamese were slaughtered. Muslims were the main victims, but in many cases, again, people didn’t bother to differentiate between ethnic or religious groups. Indira Gandhi responded with plans for a barbed-wire border fence, which the subsequent government of Rajiv Gandhi promised to implement.

Assam is useful in understanding the wider problems India faces. As elsewhere, Assam’s terrain makes it almost impossible to secure the border fully. It shares only 163 miles of frontier with Bangladesh, but some of this is the Brahmaputra River, which floods each year and changes course, making it difficult to fix a permanent boundary marker.

Since 1971, Assam’s population has more than doubled, from 14.6 million to over 30 million, much of which is due to illegal immigration. Hindu nationalists have argued that the area might have a Muslim majority by 2060. In 2015 there were 19 million Hindus and 11 million Muslims, nine of the twenty-seven districts being majority Muslim. Equally important, the 2017 census showed that people who are ethnically Assamese are now a minority in the state as a whole, and as people continue to arrive, that proportion will continue to drop.

After the murderous riots of 1982, parliament passed the Assam Accord in 1985, cosigned both by the national and state governments and by the leaders of the violent movements that had helped agitate the unrest three years earlier. The accord was intended to reduce the number of migrants in the area and referred back to the Pakistan war of 1971. Those who had arrived before 1971 could stay on certain conditions, but all foreigners who had entered Assam on or after March 25 of that year—the day on which the Pakistani army began full-scale operations against civilians—were to be traced and deported, as by 1985 Bangladesh was considered to be sufficiently stable for refugees to return.

It didn’t work. Of the 10 million who had fled Bangladesh during the war, millions remained in India, and more kept coming. As a result, over the years the fences have become longer, taller, and increasingly high-tech. The central government has focused on wall building rather than enforcing the accord and creating a legal framework for a solution. All the while the human cost has been rising: according to Human Rights Watch, in the first decade of this century, BSF personnel gunned down an estimated nine hundred Bangladeshis as they attempted to cross the border.

Most people willing to take the risk do make it into India. But once there, they find themselves in a legal nightmare. India has no effective national refugee or illegal-immigrant laws. It has not signed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention on the grounds that it doesn’t take into consideration the complexities of regional problems. Instead, all foreigners come under the 1946 Foreigners Act, which defines a foreigner as “a person who is not a citizen of India,” which may have the benefit of succinctness but is of limited use in deciding who is a genuine refugee, who qualifies for asylum, and who is an economic migrant.

The ongoing problems—the resentment of the Indian population, the murky status of the immigrants themselves—highlight the difficulties faced anywhere in the world when proper systems aren’t in place to deal with large population influxes, especially when moving from one developing country to another.

Sanjeev Tripathi, the former head of India’s foreign intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing, argues that India needs a new law to define refugees and illegal immigrants. It must also come to an agreement with Bangladesh that Dhaka will take back Bangladeshis and issue them documents, and that “this would have to be followed by concerted action to detect Bangladeshi immigrants, assign them to separate categories of refugees and illegal migrants, resettle or repatriate them, and prevent any further influx.” As he says, the current system has “substantially contributed to changing the demographic pattern in the northeastern states of India, where the locals feel overwhelmed by the outsiders. This has adversely affected their way of life and led to simmering tension between the two sides.”

The legal aspect of this is achievable through domestic political will; however, the diplomatic cooperation required from Bangladesh is more problematic. It not only prevaricates regarding the administrative paperwork sometimes required to take back migrants, but there are myriad stories of Bangladeshi guards pushing returning Bangladeshis back across the border into India, especially if they are from the Hindu minority.

An added problem is rounding up those deemed to be illegal. Millions of them are well embedded inside India; they often hold identity cards called Aadhaar, which do not distinguish them from Indian citizens for simple identification purposes, although they cannot be used to access all the facilities afforded an Indian citizen. Furthermore, in regions such as West Bengal the problem is compounded as the features and dialect of a Bangladeshi and a West Bengalese are hard to tell apart.

Another ongoing battle in Indian politics is over whether Bangladeshi Hindus should be granted citizenship on the grounds that they have fled persecution. When the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) gained power, it took this issue into account; after all, the 2014 party manifesto included, “India shall remain a natural home for persecuted Hindus and they shall be welcome to seek refuge here.” However, the BJP has dragged its heels, well aware that although Muslim immigration is the greater concern for many voters in the border states, all outsiders face degrees of hostility.

Many supporters of the BJP government take a robust view of what is required and demand policies that might appear harsh to some people. These include criminal proceedings against anyone harboring an illegal immigrant, and banning illegal immigrants from working if they do not voluntarily register with the authorities. In the 2014 national election campaign Narendra Modi, the BJP leader, repeatedly promised that he would tighten border controls and warned illegal immigrants from Bangladesh that they needed to have their “bags packed.” He went on to become prime minister.

In 2017 the BJP president, Amit Shah, accused politicians in the opposition Congress Party, who are against deportations, of wanting to make Assam a part of Bangladesh. Many in government see the problem in national security terms. Seen through the Indian security lens, the problem looks like this: Pakistan has never forgiven India for helping Bangladesh gain independence. To sow discord, it promotes a strategy known as “forward strategic depth.” It encourages illegal immigration and sponsors cross-border terrorism from Bangladesh, supporting the activities of groups such as Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami and Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh and the movement of hundreds of their fighters into India. The theory continues that by changing the Hindu-Muslim demographics in Indian regions bordering Bangladesh, political parties will form that will demand autonomy and eventually independence, thus creating a new Muslim homeland. There is even a name for this imagined future state formed out of Assam and West Bengal: Bango Bhoomi. Thus, the theory concludes, India is weakened and Pakistan gains a foothold next to Bangladesh.

Those who think such a plan exists struggle to find hard evidence of it, but point to the changing demographics to bolster their argument. State-to-state relations between India and Bangladesh are cordial, but the fraught internal politics of the postpartition subcontinent, of Hindu and Muslim nationalisms, means that politicians often pander to the emotions of identity.

Whether or not the Bango Bhoomi theory is true, many nongovernment experts in border control argue that walls and fences are of limited use in preventing the flow of people, and that they are especially ineffective in combating terrorism. Dr. Reece Jones says that despite the vast sums spent on building the new high-tech India-Bangladesh fence, it “likely has no impact” on terrorist infiltration because “a terrorist often has the funds to pay for fake documents and simply cross the border at checkpoints or travel with valid documents.” He also observes, “The threat of terrorism is used to justify walls, but the underlying issue is almost always unauthorized movement by the poor.” Talk of Bango Bhoomi is not welcomed in Bangladesh, which views the Indian fence building as arrogant, aggressive, and damaging to the countries’ relationship.

Many Bangladeshis feel hemmed in: to their east, west, and north is the Indian fence, and to their south, the Bay of Bengal, the sea. And the sea is getting closer every year.

Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. It is smaller than the US state of Florida but is home to 165 million people, compared to Florida’s 21 million, and the population is growing rapidly. Most of the country is situated at sea level on the Ganges delta. It has hundreds of rivers, many of which flood each year, displacing millions of people. Most of them do eventually return to their land as the waters subside; however, many climate experts predict that within eighty years there will be at least a 2ºC rise in land temperature and a three-foot rise in sea level. If that happens, a fifth of Bangladesh will disappear under the waves. Some of the areas most at risk are in the coastal regions that abut India such as Khulna, Satkhira, and Bagerhat, but around 80 percent of the country lies just above sea level.

Upriver, reduced glacial melt from the Himalayas has already turned some of Bangladesh’s precious fertile land into desert. This is expected to continue and is driving hundreds of thousands of people from the rural areas into the cities, sometimes simply to find fresh water after their supplies are contaminated by the sea encroaching into the rivers. The rapidly growing urban areas are ill prepared to accommodate them. The International Organization for Migration estimates that 70 percent of Dhaka’s slum population arrived in the capital because of environmental disasters such as flooding or hurricanes.

Many parts of the world are already seeing “climate refugees,” and tens of millions more are destined to be, heading mostly for urban areas, as even small changes to climate can have catastrophic results for local populations. In Africa, for example, droughts over the last few decades have created severe famine in many regions, while the Sahara Desert is also expanding slowly southward. But in Asia, climate refugees are mostly trying to escape floods. A 2010 study published by the London School of Economics suggests that of the top ten coastal cities most exposed to flooding, nine were in Asia. Dhaka was third behind Kolkata and Mumbai.

When you apply this predicted future to a country such as Bangladesh, where modern health care is scarce and education levels low, if a fifth of the land is flooded, and some of the rest is no longer fit for agriculture, then obviously huge numbers of people will move. Some will try to get to the West, but millions, especially the poorest, will head for India and run up against the fence and the border guards. India will then have an even greater humanitarian and political problem on its hands than now.

Muslims make up about 15 percent of Indians, or some 200 million. But in Bangladesh about 90 percent of people are Muslim. A crisis of mass migration would throw up a number of questions. Given the existing tensions with illegal immigrants, how many Bangladeshis would India take? How many would the majority population accept, especially in the border states, without riots breaking out and political parties rushing to extremes? Would India give preference to the Bangladeshi Hindus on the grounds that they suffer the most, given the levels of religious discrimination they claim to endure? Both countries already struggle with these issues, but the worst-case scenarios of flooding would greatly exacerbate them: climate change and economic hardship cause further movements of displaced people, who are not easily integrated culturally and economically into other nations.

Bangladesh has its own difficulties with displaced people. The Rohingya are a minority group of Muslims in the majority-Buddhist state of Myanmar. About 750,000 Rohingya live in the region of Arakan, which borders Bangladesh. They are ethnically related to the Chittagonians of southern Bangladesh, and they have a problem. The Rohingya are stateless, having been denied citizenship on the basis of ethnicity. In 1982 the Myanmar dictatorship drew up a citizenship law listing the 135 national “races” it claims were settled in the country prior to the beginning of British colonization of the Arakan region in 1823. Despite evidence that the Rohingya were present in the area as long ago as the seventh century, the junta classified them as not being from Myanmar. The Rohingya endure severe travel restrictions, find it difficult to get into business, and face an often fruitless struggle to register the births and marriages in their communities, thus being further isolated.

In the early 1990s up to 250,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh amid reports of religious persecution, murder, rape, torture, and forced labor by the Myanmar military. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) regarded them as refugees, and at first Bangladesh accommodated them. But, faced with ever-increasing numbers, it started to forcibly deport tens of thousands back across the border, often amid clashes between the refugees and the Bangladeshi military. By the middle of the decade all but about twenty thousand were back in Myanmar. However, it is impossible to know for certain how many there are, as the Bangladeshi government stopped registering them and subsequently asked aid agencies to desist from helping the unregistered—so as to discourage others from coming. Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world, Bangladesh has taken in up to half a million refugees this century, but is woefully ill equipped to deal with them.

In 1998 the UNHCR wrote to the military government in Myanmar demanding equal treatment for the Rohingya following allegations of widespread discrimination and ill treatment. The junta wrote back, “They are racially, ethnically, culturally different from the other national races in our country. Their language as well as religion is also different.” In recent years anti-Rohingya violence has increased again, with villages and mosques set on fire and people murdered, particularly in response to an attack on border police by a Rohingya militant group in August 2017. The number of people trying to get into Bangladesh has consequently risen dramatically again: over six hundred thousand were on the move in the second half of 2017 alone.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya are now living in shantytowns around the Bangladeshi port town of Cox’s Bazar or in UNHCR camps. In a poor, overcrowded country that struggles to take care of its own citizens, humanitarian resources are spread thinly, and these immigrants are often feared as a source of lawlessness and crime, being outside of society with no legal way of working. Some in Bangladesh have demanded tighter border controls in the wake of the latest influx of refugees; however, some have also called for a stronger humanitarian response. Unrest in the region could attract terrorist organizations, which would take advantage of the conflict, playing on the religious and ethnic divisions and spreading extremist ideas among the affected minority groups. The region could become a hotbed for radicalization, further inflaming the violence that has erupted there.

Bangladesh is set on returning the refugees as soon as possible; Myanmar has tended to prevaricate, suggesting that the refugees will be taken back, while planning to upgrade and expand the barrier along its 170-mile border with Bangladesh. Land mines have allegedly been laid to prevent people from returning. Furthermore, what could the Rohingya expect to return to? More than two hundred villages have been burned to the ground, and systematic discrimination against them still exists.

No obvious solution is in sight as long as Myanmar continues to hound its minorities; another border, therefore, looks set to remain a source of tension and instability.

* * *

The surging populations of the subcontinent are facing the challenges of the twenty-first century in a man-made geography of fences and national borders that has little respect for history.

To the south of Assam, the Rakhine Mountains separate India from Myanmar and are covered in dense jungle. People have made their way through the jungle to try to claim asylum in India, but not in such great numbers as to make it a national issue. Of more concern is the insurgency being fought by the tribal Naga people within Myanmar, which sometimes spills over into India and has led to the construction of a fence, not by the Indians but by Myanmar, along parts of that section of the border.

The Nagas are a collection of forested-hill tribes. They have cultural traditions in common, although their language is varied—most speak different dialects of the Naga root language that are unintelligible to outsiders and sometimes even to one another. Some tribes only gave up head-hunting a few decades ago after converting to Christianity, but they remain tied to many original cultural practices and do not see themselves as being from either Myanmar or India.

Following the declaration of the state of India in 1947 and the state of Myanmar the following year, the Naga people found themselves divided by the newly declared sovereign borders. An armed struggle broke out in the 1950s when some Naga tribesmen on the Indian side of the border began to agitate for independence from New Delhi. The creation of the state of Nagaland (India’s smallest) in 1963 reduced the level of violence but did not result in a permanent settlement. By the 1970s the militants had been driven into Myanmar, but continued their struggle from there alongside other Naga tribes. An estimated 2 million Nagas are now spread across both sides of the frontier, an area that Naga nationalists want to turn into a united homeland.

The Myanmar government, which is at any time usually dealing with several internal insurgencies, did little to prevent the Nagas from using the region to train and equip their militias and conduct frequent cross-border raids. This has been a major source of irritation to the national government in India and the state governments in Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. In 2015, following a raid that killed eighteen Indian soldiers, the Indian military conducted a lightning nighttime cross-border operation, the first in many years. Helicopters dropped Indian commandos at the border, who pushed several miles into Myanmar before attacking two Naga rebel camps. New Delhi claimed that around thirty-eight rebels were killed, although that figure is disputed.

Publicly the Myanmar government had to pretend to be angry about the incursion, but it had occasionally crossed into the Indian states of Manipur and Mizoram in hot pursuit of “terrorists” from the Chin and Arakanese rebel groups and so in private tolerated the incursion into its sovereign territory. Undiplomatically, the Indian government trumpeted the whole affair, causing Myanmar to think hard about how to prevent further such actions. An added impetus was China’s increasing influence in Myanmar, which could be counterbalanced by forging stronger ties with India.

In early 2017, with Indian army operations continuing against the insurgents, Myanmar began to construct a short border fence in the Naga Self-Administered Zone, a region where the Naga people enjoy limited autonomy. Officially, India is not involved with the fence; however, New Delhi does give Myanmar $5 million a year to promote “border areas development” in the region. The fence is there in the name of mutual national security, both to prevent the Naga militia from entering India and to ensure that no one from India constructs any buildings on Myanmar’s side of the frontier. The Myanmar government says its purpose is not to restrict the movement of ordinary people, but the fence does nevertheless threaten to split up communities and families, who until now treated the nation-state borders as imaginary. The two governments had acquiesced in this with the Free Movement Regime, which allowed the Nagas to travel up to ten miles on either side of the border without requiring visas. This helped to grow border markets, where the Myanmar Nagas could buy Indian products mostly unavailable at home and which had previously been smuggled across the border. All of this is now under threat and will further divide a people who regard themselves as neither Indian nor Burmese, but as Naga.

* * *

Not all of India’s borders are so troubled that they’ve been fenced off. India and Bhutan have a close relationship, and because India accounts for 98 percent of Bhutan’s exports, neither side is contemplating “hardening” the border. Although India’s relations with Nepal are more strained, especially after a four-month “blockade” of the border in 2015, New Delhi does not see the need to fence what is a thousand-mile frontier, especially as it is keen to maintain influence in the country and not permit a vacuum it knows the Chinese would fill.

A natural barrier—the Himalayas—separates China and India along much of their twenty-five-hundred-mile-long frontier, so they are pretty much walled off from each other. The Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh is claimed by China, but the dispute has not resulted in a hostile border, although 2017 saw a nonviolent standoff in the Himalayan Doklam Plateau after India accused China of building roads. New Delhi fears this could allow China to move armored columns across the plateau and down into India. If so, China could cut what is known as the “chicken’s neck,” a relatively narrow corridor of land that would then divide the bulk of India from its northeastern states.

Where we start to hit real trouble again is along the Indian border with Pakistan. Since partition, relations between the two countries have been fraught, and this is very much a “hot” border. India has built a 340-mile-long barrier along the disputed Line of Control (cease-fire line) inside Kashmir, a region both countries say is their sovereign territory. Most of it is 150 yards inside the Indian-controlled side and consists of double-row fencing up to twelve feet high. It is similar to the West Bengal–Bangladesh fence, with motion sensors and thermal-imaging technology linked to a command system to warn rapid-response border troops of any incursions. The strip of land between the two fences is mined.

In 1947, under the Indian Independence Act, states were given the choice of joining India or Pakistan or becoming independent. Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of Kashmir, was Hindu, whereas most of his people were Muslim. The maharaja chose neutrality, sparking a Pakistan-encouraged Muslim uprising, which in turn led the maharaja to cede Kashmir to India. That sparked a full-scale war; as a result the territory was divided, but on both sides the majority of the population is Muslim. Another war followed in 1965, and serious clashes occurred in 1999 between Indian forces and Pakistani-sponsored groups. By this time both nations were nuclear armed, and the prevention of conflict between them became even more important. A low-level insurgency continues on the Indian-controlled side of Kashmir, and this, the bitterest dispute between the two powers, sporadically threatens to worsen. Talks come and go, gestures of friendship are made, often through cricket matches, but India has concluded that until the issues are resolved, one way to keep the peace is to build barriers to prevent infiltrations by insurgent groups that could spark full-scale fighting.

This vast project has taken decades, but New Delhi is now filling in the gaps in its northern and western border defenses, having already fenced parts of the Punjab and Rajasthan in the 1980s and 1990s, and is working to “seal” its entire western border, from Gujurat on the Arabian Sea right up to Kashmir in the Himalayas, with what it calls a Comprehensive Integrated Border Management System (CIBMS). Some of this terrain is already difficult to cross due to swampland in the south, and to the north the Thar Desert.

The CIBMS is a similar system to that on the Bangladesh frontier, but this is a much more active border, and the danger of military action between India and Pakistan is ever present. The new barriers going up all have radar, thermal imaging, night vision, and other equipment linked to control rooms that appear every three miles. Two hundred thousand floodlights are planned, and the 130 sectors that are riverine will have underwater lasers linked to the control centers. The Indian military is also looking at buying unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) capable of identifying a newspaper from sixty thousand feet, as well as equipment that can detect human movement tens of miles away. Pakistan has criticized the building of the barriers, saying they violate UN resolutions and local agreements; but India says that incidents of cross-border shelling and militia raids are being lessened by its measures.

Issues such as this are open to interpretation. While India might see the construction of a fortified lookout post as defensive, Pakistan could regard it as a launchpad for an offensive. The India Pakistan Border Ground Rules Agreement (1960–61) sets out how to accommodate both points of view, but it has never been signed by either side, and in practice such agreements are arrived at ad hoc. Each year can throw up a matter of contention that had not necessarily been clarified in the early 1960s. For example, in 2017 India erected a 360-foot-high flagpole at the Attari border in Punjab. Pakistan immediately accused India of violating the agreement, saying that the flagpole, which could be seen from the city of Lahore, might have been fitted with cameras to allow India to spy on Pakistan.

The situation in Kashmir is more formal. Even without an agreement on where the border should be, in theory behavior on each side of the Line of Control (LoC) is regulated by the Karachi Agreement of 1949. It says that no defenses should be constructed within five hundred yards of each side of the line, a stipulation frequently ignored by both sides. The fragile cease-fire is also frequently broken. Not only do cross-border shootings occur between Indian and Pakistani regular forces, but New Delhi accuses Islamabad of sponsoring terrorist groups to cross into the Indian-controlled side to foment violence and even carry out attacks in Indian cities. Since the early 1980s the two countries have engaged in sporadic artillery duels high up on the Siachen Glacier close to the LoC. Located on the Karakoram Range in the Himalayas, this is the world’s highest combat zone. At almost twenty thousand feet above sea level Pakistani and Indian soldiers face off in one of the most hostile climates possible. Tours of duty at the higher levels are only twelve weeks long as lack of oxygen can prevent sleep and cause hallucinations. The soldiers exchange fire, but frostbite causes more casualties than high explosives.

Kashmir remains the biggest issue between the two countries. They share a border drawn by outsiders; it divided communities and now stands as a fortified monument to the enmity between two nuclear-armed nations.

Pakistan’s 1,510-mile-long western border with Afghanistan was also shaped by outsiders. The original Muslim conquerors used Afghanistan as a jumping-off point from which to invade India, and the British then used it to delineate the western periphery of the jewel in the crown of their empire. The border is still known as the Durand Line, after Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. In 1893 he and the Afghan emir Abdur Rahman Khan drew the line that effectively established Afghanistan as a buffer zone between British-controlled India and Russian-controlled Central Asia.

It was, is, and will remain a problematic frontier. It separates Pashtuns on each side of it into citizens of different countries, a separation many do not accept. For that reason, and because Afghanistan claims some territory east of the line, Kabul does not recognize the border.

Pakistan, desperate to prevent Pashtun nationalism leading to secession, prefers a weak Afghanistan. This, in part, is why sections of the Pakistani military establishment covertly support the Taliban and other groups inside Afghanistan—even though this has come back to bite them east of the Durand Line. There are now the Afghan Taliban and the Pakistan Taliban, which have close ties and similar views, and both of which kill Pakistani civilians and military personnel.

By the spring of 2017 things had become so bad that Pakistan announced plans to build a fence in two districts along the border in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. This, it was said, was to combat cross-border operations by the Taliban. However, even if the Pakistanis manage to construct fencing in this difficult and mountainous terrain, the genie is out of the bottle: the Taliban are inside the country and able to move around.

Meanwhile, to the south of the Durand Line is the Pakistan-Iran border, and here it is the Iranians who are building a wall. A ten-foot-high, three-foot-thick concrete wall is rising along parts of the frontier. This follows years of drug smuggling, but also the infiltration of Sunni militia groups from Pakistan into Iran, which is a majority-Shia country. In 2014 Iranian troops crossed the border to take on a militant group; they then had a firefight with Pakistani border guards. Relations remain cordial between the two states, but in the age of walls Iran is attempting physical separation to prevent the situation from deteriorating, thus continuing the trend set by India, Bangladesh, and other nations in the region.

All of the above examples fly in the face of the dream of some politicians, and many people in the business community, of creating a vast open trading zone in the subcontinent. India in particular has been reaching out to Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh to develop plans for easier travel and trade across the region. Transnational road and rail links are envisaged, with streamlined crossing points and even, eventually, a huge reduction in border controls similar to the ones in parts of the EU. Progress, however, is slow, and the border-building programs now seen in most of the countries go against the practicalities and spirit of regional cooperation.

We see the deepest divide on the India-Pakistan and the India-Bangladesh borders because this is, at heart, a religious one. India is a Hindu-majority country with a secular democratic system and traditions, but in recent years it has seen a sharp growth in Hindu nationalism. Pakistan is an Islamic republic with a troubled democracy and a history of military rule, while Bangladesh, although nominally a secular republic, has become increasingly religious in both the state sector and public life, with minorities and atheists at serious risk of being murdered for their beliefs.

* * *

Not all the walls in the subcontinent are made of stone or wire; some are invisible, but they are present all the same. India has massive internal divisions on a scale and level of prejudice that would, if repeated in some countries, be regarded as a shocking scandal requiring international condemnation—yet the world is mostly silent about the horrors of the Indian caste system.

The system has echoes of apartheid, albeit with significant differences—not least being that it is not enshrined in the country’s laws. Nevertheless, it has created a segregated society within which some humans are classified as superior beings and others as impure, and people must remain “in their place.” Certain categories of people are denied entry to jobs and have their movements restricted. The system ensures that a ruling caste maintains positions of privilege and condemns others to a life of poverty in which they are subject to violence without recourse to legal redress. The walls between the castes are mostly invisible to outsiders.

The roots of the caste system are religious and date back more than three thousand years. Hindus are divided into rigid hierarchical groups based on what they do for a living. This is justified in the Manusmriti, the most authoritative book on Hindu law, which regards the system as the “basis of order and regularity of society.” Higher castes live among each other, eating and drinking places are segregated, intermarriage is usually banned or at least frowned upon, and in practice many jobs are closed to lower castes.

Some preindustrial European societies were based on the hereditary transmission of occupation, which ensured the class system remained intact, but it wasn’t based on religion and has been massively weakened by modernity. The Indian caste system is also fraying in some places due to the pressures of urban living, but its religious basis ensures that it is embedded in everyday life. India remains a predominantly rural society, and thus the ability to hide your roots and avoid your religious heritage is limited. However, even as the population slowly shifts to the cities, the caste system endures because the religious system does.

The system has four main categories of people: Brahmans, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras. Brahma is the god of creation, and the Brahmans, who dominate education and the intellectual fields, are said to have come from his head. The Kshatriyas (from Brahma’s arms) are warriors and rulers, while the Vaishyas (from his thighs) are traders, and the Sudras (from his feet) do the menial work. These four categories are split among about three thousand castes, which are in turn divided into twenty-five thousand subcastes.

Outside of the system are the untouchables, now mostly called the Dalits, “broken people.” In India, if you see someone disposing of a dead animal or sweeping the streets, chances are the person is a Dalit. Anyone cleaning toilets or working in sewers is almost certainly a Dalit. They are much more likely to be victims of crime, especially rape, murder, and beatings, although conviction rates for people charged with crimes against Dalits are significantly lower than for crimes committed against other groups. In many rural areas Dalits are still not allowed to draw water from public wells or enter Hindu temples. The caste you are born into dictates the job you will have, and lower-caste people will find themselves with a broom in their hands even if they have a university education. All of the lower castes suffer from discrimination, but at the very bottom are the Dalits.

The caste system has an element of skin color that many people like to downplay, but it is there nonetheless. A 2016 genetic study by Hyderabad’s Centre for Cellular & Molecular Biology discovered a “profound influence on skin pigmentation patterns” within the class structure, the lighter skin tones being predominantly found among the higher castes. National secular laws have in theory banned discrimination, but as the system is dominated by people in the higher castes who want to maintain it, the laws are not enforced. Many politicians are also reluctant to take real action as they rely on bloc votes from certain castes.

The system is deeply embedded in the culture of the country. For example, Mahatma Gandhi, who was from one of the higher castes, said, “I believe that if Hindu society has been able to stand, it is because it is founded on the caste system. . . . To destroy the caste system and adopt the Western European social system means that Hindus must give up the principle of hereditary occupation, which is the soul of the caste system. Hereditary principle is an eternal principle. To change it is to create disorder.” To be fair to Gandhi, he did later speak out against the caste system and the treatment of the untouchables. However, he continued to defend the idea of varnas, or social classes. He said everyone was assigned a hereditary calling that defined what job he or she should do, but that this did not imply levels of superiority. Varnas, he wrote, were “the law of life universally governing the human family.”

This sense of entitlement and “natural law” remains endemic. The Dalits, and other castes, have been using the secular laws to try to level the playing field. They have had some success, but it has also led to rising levels of violence against them. India’s 2014 National Crime Records showed a 29 percent increase in crime against lower-caste people over two years as they increasingly resort to the law to seek justice. Dalits owning or buying land is the most common cause of violence against them by local communities determined to keep them at the bottom of society.

Reliable national statistics for caste numbers are difficult to find because the last time the Indian census included caste was 1931. Then the untouchables constituted 12.5 percent of the population. Now, despite twenty-seven years of affirmative action, they remain the poorest and most oppressed of India’s people. The major government, judicial, diplomatic, and military positions, as well as senior posts in major companies, academia, the media, and the education system, are all overwhelmingly dominated by Brahmans despite the fact that they compose roughly 3.5 percent of the population. All societies build in social stratification, but even the elite public school system in Britain’s class-based society does not result in such a rigid, ossified social structure. Given the rural and religious base of Indian culture, it will take a long time for these prejudices to be overcome—should enough Indians even want to. The system survives partially because its supporters openly argue that it binds society together: India needs to be protected from the fragmentation of society witnessed in Europe after the Industrial Revolution. Its opponents counter that it is immoral and holds the country back as it cannot harness all of its human talents.

Over the decades since independence some Dalits have surmounted the obstacles and risen to prominence, notably K. R. Narayanan, who served as president between 1997 and 2002. With people increasingly moving from the countryside to the cities, the invisible walls are beginning to grow weaker: what caste you are is less obvious in the city, some urbanites do not take the system so seriously, and even some caste intermarriages are now occurring. But P. L. Mimroth of the Centre for Dalit Rights believes that the roots of discrimination are still so deeply embedded in the national psyche that it will take generations until the spirit of the laws against the caste system is truly accepted: “We were wrong to believe that education would eradicate untouchability. It will take more than one hundred years to change that.”

As the statistics show, the system is still alive and well throughout the country: tens of millions of people are denied basic human rights, not by law but by culture. This is not the image of India most people have. Generations of tourists and student backpackers return from India infused with the spirit of Hinduism, which promotes friendliness, nonviolence, spiritualism, and vegetarianism. Few see that alongside that is one of the most degrading social systems on the planet.

In 1936 the great Indian intellectual B. R. Ambedkar was invited to deliver the annual lecture to a Hindu reformist group. He submitted his speech, which included, among many other challenging statements, “There cannot be a more degrading system of social organization than the caste system. . . . It is the system that deadens, paralyses and cripples the people from helpful activity.” The lecture was canceled on the grounds that parts of it were “unbearable.” Ambedkar published his work as an essay later that year.

In the twenty-first century Indian society is far from “deadened”—indeed India is a vibrant, increasingly important country, embracing a range of high-tech industries—yet within it are millions of barriers to progress for tens of millions of its citizens. The walls around India are designed to keep people out, and those within to keep people down.

The divides throughout the subcontinent are becoming ever more apparent, exacerbated by the continuing and growing movement of people escaping poverty, persecution, and climate change. If the majority of scientists are correct in their predictions of climate change, then it is obvious people will continue to be on the move this century. A wall has yet to be built that can withstand that much weight pressing against it. The barriers can and will be built as a partial, one-sided, temporary holding “solution,” but unless prosperity is also built, everyone is going to lose. In an attempt to control the regional demographics, the barriers along the majority of the thousands of miles of frontiers are now being built higher and wider and are becoming more technologically sophisticated. As we’ve seen, though, such barriers don’t stop people from attempting to cross anyway—many don’t have any other choice but to try—and increasingly violent policing of borders can lead to terrible human consequences. Felani Khatun paid with her life, and down in the delta plains of Bangladesh are millions more like her.