A Sahrawi girl with Sahrawi flag in front of the Moroccan Wall, separating Western Sahara between territory controlled by Morocco and that held by the Polisario Front.

The forces that unite us are intrinsic and greater than the superimposed influences that keep us apart.

—Kwame Nkrumah

A Sahrawi girl with Sahrawi flag in front of the Moroccan Wall, separating Western Sahara between territory controlled by Morocco and that held by the Polisario Front.

At the top of Africa is a wall of sand, of shame, and of silence. The Moroccan Wall runs for seventeen hundred miles through Western Sahara and into parts of Morocco. The whole construction separates what Morocco terms its Southern Provinces along the Atlantic coast from the Free Zone in the desert interior—an area the Sahrawi people call the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. The barrier is built of sand piled almost seven feet high, with a backing trench and millions of land mines stretching several miles into the desert on each side. It is thought to be the longest continuous minefield in the world. Every three miles or so is a Moroccan army outpost with up to forty troops, some of whom patrol the spaces between the bases, while two and a half miles back from each major post are rapid-reaction mobile units, and behind those, artillery bases. The length of the wall is also dotted with radar masts that can “see” up to fifty miles into the Free Zone. All of this is intended to keep fighters from the Sahrawi military force, called the Polisario Front (PF), well away from the wall and the areas Morocco considers its territory.

It is a harsh place. By day the heat can reach 122°F, and at night the temperature can drop to almost freezing. Frequently the sand-laden sirocco wind blows through the arid land, turning the air a mustard color and restricting visibility. To an outsider it is a hostile, forbidding region, but to the Sahrawi people, it’s home.

A Western Saharan independence movement existed prior to Spain’s withdrawal from the region in 1975. As the Spanish left, 350,000 Moroccans took part in the “Green March”—they walked into the region and claimed it as Moroccan territory. Spain subsequently transferred control to Morocco and Mauritania; the government in Rabat effectively annexed the territory and sent in twenty thousand troops, who were immediately confronted by the PF. The fighting lasted sixteen years and took the lives of tens of thousands of people. Despite their superior numbers and modern military equipment, the Moroccan army could not subdue the PF and their guerrilla tactics. In 1980, Morocco began building what became known as the Wall of Shame, finishing it in 1987.

Now there is silence. Western Sahara is not so much a forgotten conflict as a conflict few people have ever heard of. The Sahrawi people who live on each side of the wall speak the Hassaniya dialect of Arabic, feel culturally different from Moroccans, and are traditionally a nomadic people, although now they are mostly urban and tens of thousands live in refugee camps. Moroccan immigration has completely changed the composition of the Western Saharan population as the government has encouraged people to settle there by offering tax breaks, subsidies, and one-off payments. The total population of the remaining Sahrawi is not known, but estimates range between two hundred thousand and four hundred thousand. Until the mid-twentieth century they’d had no concept of borders; they simply moved over a vast area, following unpredictable rainfall. Now, 85 percent of what they would regard as their traditional territory is under Moroccan control. The word Sahrawi means “inhabitants of the desert,” and that is what they wish to be—not inhabitants of Morocco. They are, like other peoples we will encounter throughout this chapter, victims of the lines drawn by others—in this case a vast line made of, and in, the sand.

Morocco is not alone in dealing with secessionist movements. Across Africa attempts are being made to break away, conflicts that descend into incredibly violent civil wars, such as those we’ve seen in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Why do so many African countries suffer such terrible strife? The reasons are many and varied, but the history of the way in which the nation-states across the continent were formed plays a crucial part.

Independence movements struggle for recognition and self-determination. The idea of the nation-state, having developed in Europe, spread like wildfire in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, calling for self-determining government for a “nation” of people—a group who to some degree share a historical, ethnic, cultural, geographical, or linguistic community.

When the European colonialists drew their lines on maps and created the nation-states that, largely, still make up the continent of Africa, they were treating a vast landmass containing a rich diversity of peoples, customs, cultures, and ethnicities with little regard for any of them—and the nation-states they created often bore no relation at all to the nations that were already there. These nations—or peoples—are sometimes referred to as tribes. Western writers are often squeamish about using the word tribe, and some Western and African academics will even tell you the colonialists invented the concept. They are simply playing with words because they are embarrassed that the word tribe has, wrongly, for some people become synonymous with “backwardness.” Nevertheless, tribes exist within many nation-states in Africa and elsewhere—it seems pointless to deny their importance.

I have a friend in London who is from West Africa. The first thing he told me about himself was his name, then that he was from Ivory Coast, and then that he was from the Mandinka tribe. This was to him a source of pride, an identification with a people spread across several West African countries in each of which they compose a significant minority. He is not unusual: huge numbers of Africans use the word tribe to refer to their nation or people and identify with whichever one they belong to. Within this there will be, to varying degrees, a shared history, customs, food, and possibly language and religion. In this the Africans are no different from any other peoples around the world; what does distinguish them is how strong this tribalism remains within many African nation-states. An English family abroad, meeting another, may well share a strained conversation along the lines of “Ah, a Brit. Where are you from?” “Milton Keynes.” “Oh, Milton Keynes,” followed by short periods of silence broken possibly by a discussion about which are the best roads into Milton Keynes. A Mandinka from Ivory Coast meeting another from Gambia when visiting Nigeria will have a lot more to talk about.

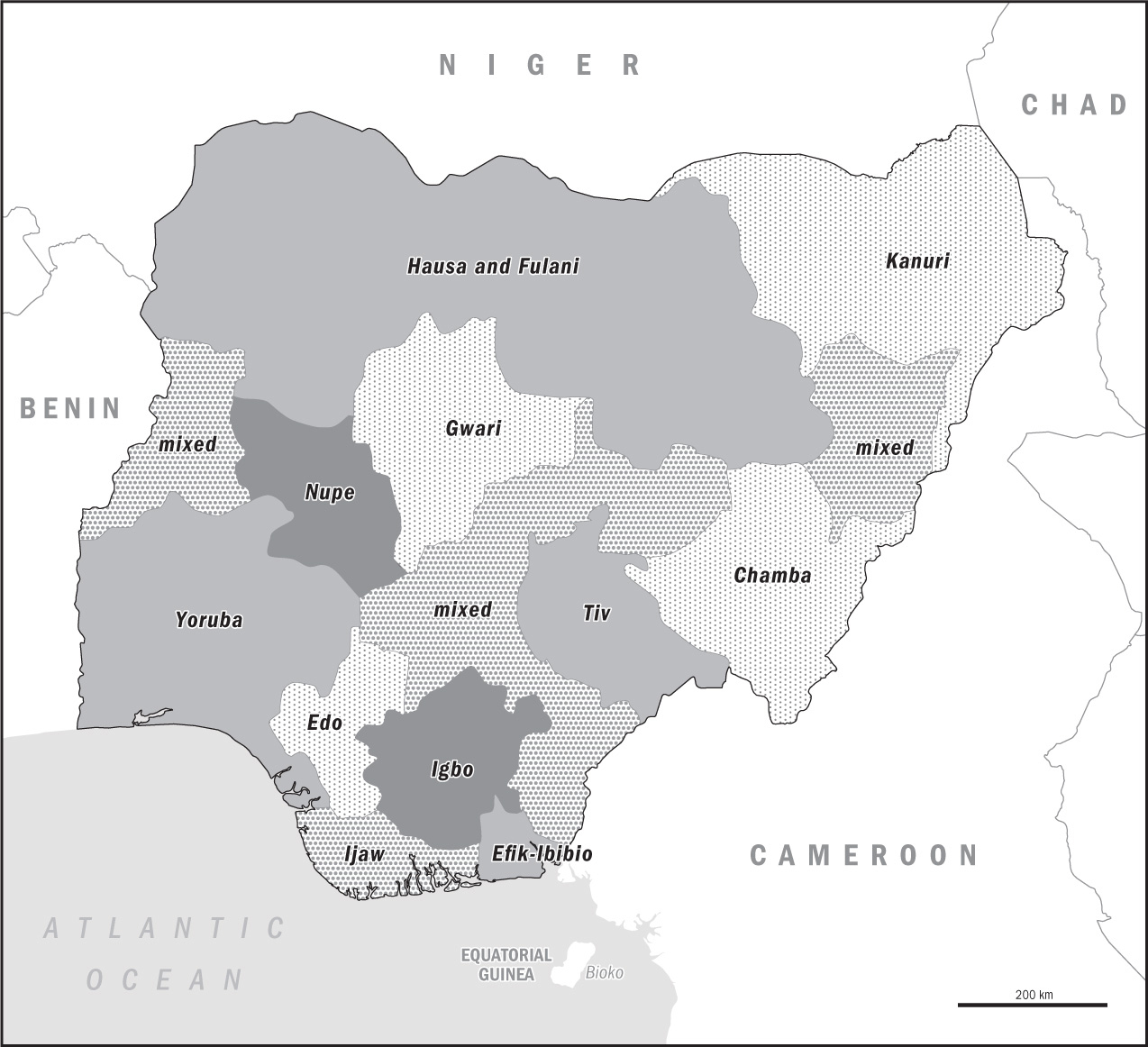

Classifications are difficult, but Africa is estimated to have at least three thousand ethnic groups encompassing a huge variety of languages, religions, and cultures. Among the largest are the Amhara and Oromo in Ethiopia, which comprise about 54 million people. Nigeria is home to four of the ten largest tribes on the continent—the Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, and Ijaw, totaling almost 100 million in a country of 186 million people. The Shona in Zimbabwe, the Zulu in South Africa, and the Ashanti in Ghana each number about 10 million. Many smaller groups and subgroups exist, however. As a rough guide, and depending on how they are counted, Nigeria alone is estimated to have between 250 and 500 tribes.

Tribalism can have many positive aspects, providing a sense of community, a shared history, values and customs, and a source of support in troubled times. Even with increasing urbanization, these tribal traditions have continued and created new communities as people group together.

Usually, as a newcomer to a city, you will head to a district where you feel socially accepted and where people will show you the ropes. Frequently that will be among folk who you identify with, which gives you the feeling of safety in numbers—this quickly leads to the re-creation of a tribe. We witness this everywhere, in every Chinatown in the world, for example, and we see it in African cities such as Nairobi in Kenya, where often people from different tribes around the country settle in districts of the city populated by those of the same tribe. A Luhya from a rural area of Kenya who moves to the capital might more quickly feel at home in the Kawangware district, even if it is one of the poorer parts of town. The Kenyan tribes have carved out extended tribal villages within Nairobi. This has been going on for decades across the continent. In the 1986 novel Coming to Birth by the Kenyan writer Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, the main character, a sixteen-year-old girl named Paulina who is from the Luo tribe, arrives in Nairobi from rural Kisumu and heads for the Makongeni district. Makongeni was, and remains, mostly populated by Luo.

The various linguistic regions of Nigeria.

While belonging to a tribe is a positive thing, a source of pride for many, in Africa—as elsewhere—one key question is the degree to which the existence of tribes holds back the forging of the biggest tribal unit, the nation-state, and the cohesion it is supposed to represent. The problem lies in the way in which the nation-states were formed.

* * *

Drive several hours east of Lagos and you can find, with some difficulty, the ruins of a massive walled city that was lost to the jungle, and then to history, for centuries. The walls are thought to have been begun in the eighth century to repel invaders. By the eleventh century Benin City was the capital of the Benin Empire, the most highly developed empire in West Africa.

When the Portuguese came across it in 1485, to their astonishment they found an urban area bigger than their own capital city, Lisbon. Situated on a plain about four days’ walk from the coast, the city was surrounded by massive walls up to sixty-six feet high and exceptionally deep ditches, all of which were guarded. The 1974 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records says, “The city walls, together with those in the kingdom as a whole, were the world’s second-largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era.” A 1990s article by Fred Pearce in New Scientist (drawing on the work of the British geographer and archaeologist Patrick Darling) stated that the walls were, at one point, “four times longer than the Great Wall of China,” although they used less material. They are estimated to have run for 9,940 miles and encompassed a population of up to one hundred thousand people.

The city appears to have been laid out according to the rules of what we now call fractal design—a complex repeating pattern exhibiting similar patterns at increasingly small scales. In the city center was the palace of the king, who oversaw a highly bureaucratic society. From this fanned out thirty main streets, about 120 feet wide, running at right angles to one another, all with narrower streets leading off them. The city was split into eleven neighborhoods. Some were lit at night by tall metal lamps with palm-oil-fueled wicks that illuminated the extensive artwork to be found across the city. Inside the city were houses, some two stories high, and walled compounds made of red clay. Outside were five hundred walled villages, all connected to one another and to the capital. A moat system included twenty smaller moats around some villages and towns.

The early Portuguese explorers were impressed with the scale of the city and the stunning works of art and architecture it contained. In 1691 Lourenco Pinto, a Portuguese ship’s captain, observed, “All the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

In 1897 this jewel of West Africa was destroyed by British troops as they tried to expand their control of the continent. After a few years of British attempts to consolidate their power over the region, the situation had descended into violence. A force of twelve hundred or so Royal Marines fell upon the city, burning the palace and people’s homes and looting religious icons and works of art. Many of the stolen Benin bronzes remain in museums around the world even today. The king escaped but later returned and was exiled to southern Nigeria, where he died in 1914.

By then most of the great city walls had been destroyed as the victorious British stamped their authority on the kingdom, blowing up large sections of the walls and incorporating the city and its surroundings into “British Nigeria.” Local people took much of what was left as building materials to make new homes, and slowly the city was depopulated. What remained was mostly forgotten about, except by people in the region. In the early 1960s archaeologists began to explore the area and map what is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as are the remains of a similar complex of walls and ditches in what is called Sungbo’s Eredo, 140 miles to the west.

Although barely anything is left to indicate that Benin City even existed, it was a prime example of the richness, diversity, and wealth of precolonial African civilizations. When these kingdoms rose to power, they were separate entities; now they are but small parts of a much larger whole—Nigeria. The Europeans’ border lines, such as those of “British Nigeria,” were often drawn according to how far European explorers had gone, rather than taking into account the existing nations and kingdoms, which had organically evolved around tribal divisions. The Europeans forcibly threw together hundreds of nations, or tribes.

The myriad African nations were never democracies, but a ruler was usually from the same wider tribe as his subjects in a system of government originating from within that tribe. When the colonialists withdrew, different peoples were told they were now grouped together in a defined area, and they were often left with a ruler who, in the eyes of many, did not have the right to rule them. The colonial legacy has a double contradiction: first, the creation of single nation-states out of multiple nations and tribes; second, the Europeans simultaneously bequeathed ideas of democracy and self-determination. Much of the current discord and conflict we see in Africa is rooted in this experiment in rapid unification.

The first generation of leaders of the independent African states understood that any attempt to redraw the colonial maps might lead to hundreds of mini wars, so they decided to work with the existing lines in the hope of building genuine nation-states and thus reducing ethnic divisions. However, most leaders then failed to implement policies to unite their peoples within these borders, instead relying on brute force and repeating the colonialists’ trick of divide and rule. The many different peoples thrown together in these newly minted nation-states had not had the beneficial experience of settling their differences and coming together over centuries. Some states are still struggling with the contradictions built into their systems by colonialism.

Angola is a prime example. It is larger than the US states of Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas, and Mississippi combined. When the Portuguese arrived in the sixteenth century the region was home to at least ten major ethnic groups subdivided into perhaps one hundred tribes. The Portuguese would have gone farther and incorporated even more nations into their colony, but they bumped up against British, Belgian, and German claims. The different ethnic groups had little in common—other than a dislike of their colonial masters. By the early 1960s enough of them had banded together to launch a war of independence. The Portuguese departed in 1975, but they left behind an invented country called Angola, which was expected to function as a united nation-state.

Imagine for a moment that colonialism had not happened, and that instead, as it modernized, Africa had followed a similar pattern to Europe and developed its own relatively homogeneous nation-states. One of the peoples of Angola are the Bakongo, who speak Kikongo, a Bantu language, and who in precolonial days had a kingdom of contiguous territory, stretching across parts of several territories including what are now Angola, DRC, and Gabon. They feel kinship with fellow Kikongo speakers in the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—together comprising around 10 million people. In the DRC they are the largest ethnic group, but in Angola they are a minority, which explains the rise of the Bundu dia Kongo movement, which is present in all three countries and wants a nation-state of Kikongo speakers based on precolonial ideas of territory. They are still working at forging a unified nation-state—as are many others with a similar history.

There is no getting away from the aspiring nationalism of peoples torn apart by the colonial era. They did not agree to join federations given names by Europeans. Then, when they were eventually able to throw the Europeans out, they were expected to feel loyalty to a system that had been imposed upon them against their will, and in which too often the main ethnic group dominated all the others. In some countries these divisions can be contained within the political sphere, but in many places the lid has blown off, bringing civil war and the rise of separatist movements.

Take, for example, the Land and Maritime Boundary dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria, which began in 1994. Both countries claimed sovereignty over an oil-rich peninsula named Bakassi. The situation deteriorated so badly it led to sporadic armed conflict between them, leading to the emergence of the Bakassi Self-Determination Front (BSDF), which issues videos of members wearing uniforms and clutching assault rifles and runs a pirate radio station called Dayspring, which calls for self-rule. Cameroon has other problems with independence-minded people. It is a mainly French-speaking country, but out of a population of 23 million, a minority of about 5 million speak English. Some of the latter claim to be discriminated against, with growing calls for autonomy for the two western provinces bordering Nigeria in which most of them live. There’s even a “president” in exile, a flag, and a national anthem ready in the unlikely event that the two provinces unite as Southern Cameroon.

There are many other examples. Casamance, a region in the southern part of Senegal, has been fighting for autonomy. Kenya has the Mombasa Republican Council, which wants independence for the country’s coastal region, arguing that it has its own distinct culture and should not have been included as part of Kenya when it won independence from the UK. Its slogan, in Kiswahili, is Pwani si Kenya—“the coast is not Kenya.” The Kenyans also have a problem with terrorism coming from Somalia, and so authorities spent much of 2018 building a partially electrified fence along the entirety of their shared border.

Few of the numerous secessionist movements are likely to be successful in the near to medium future, but breakaways cannot be ruled out—some have managed it in recent years. Ethiopia lost Eritrea to an independence movement and still faces separatist factions in its Ogaden and Oromia regions, while Sudan is split into two countries, South Sudan having become the world’s newest state in 2011. Sadly, the situation there has degenerated into civil war: the dominant Dinka tribe was quickly accused of discriminating against the Nuer, Acholi, and others, which led to fighting between them. The war has cost several hundred thousands lives and caused more than a million people to flee their homes.

It’s a familiar story in the recent history of Africa. Perhaps one of the worst examples was in Nigeria, where a massacre of the Igbos preceded the civil war of 1967–70 and the short-lived Republic of Biafra; in total more than 3 million were killed, and Nigeria has a continuing problem with Biafran ideas of nationhood. But this is far from the only case. Burundi is another. Ethnically it is about 85 percent Hutu, but the 14 percent Tutsi minority are politically and economically powerful, and the country has long been ravaged by the tensions between them. In 1965 a coup attempt against the king, who was a Tutsi, sparked ethnic fighting that killed at least five thousand people. In 1972 mass killings sparked an invasion by Hutu rebels who had based themselves in Zaire. It is thought that over the following four years almost two hundred thousand people died. Smaller outbreaks of violence plagued the 1980s before a full-scale civil war broke out in 1993 and continued until 2005. This time Hutu president Melchior Ndadaye was killed by Tutsi assassins, setting off a chain of events that pitted the two sides against each other. The last few years have witnessed low-level violence, with about four hundred thousand Burundians fleeing the country, most heading for Tanzania.

In Rwanda around eight hundred thousand Tutsis and moderate Hutus were murdered in the 1994 genocide. The Democratic Republic of the Congo contains more than two hundred ethnic groups and has been suffering terrible violence since 1996—estimates vary, but some put the death toll as high as 6 million, and the agony of the conflict continues today. A whole host of other countries, including Liberia and Angola, have also endured widespread and sustained conflict. The factors behind the violence are complex and include the imposition of borders, a lack of development, and poverty; but without doubt the ethnic divides are significant. Since the nations still frequently cross nation-state borders, conflict in one can quickly spread to another.

All nation-states have differences with their neighbors, but in most other parts of the world territorial disputes arose organically over long periods and were based on geography and ethnicity. In many cases they have been settled. However, the African experience is of relatively recent geographical and ethnic contradictions being built into the whole region by outsiders. Yes, we’re back to colonialism—because there will be no getting away from it until the Africans can distance themselves from its effects. Given the scale of the social engineering, sixty to seventy years of independence is no distance at all.

It does not help that the European borders are still the basis of any diplomatic resolution of territorial disputes—as we saw in Morocco and Western Sahara, which are still abiding by the lines drawn by Spain. Unsure of how to respond or with whom to side, the international community has recognized neither Morocco nor the Polisario Front’s claim to Western Sahara; the region is on the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories, meaning that the area hasn’t officially been decolonized. So technically Spain is still the administering power in Western Sahara, even though in practice most of it is under Moroccan control.

Another example is the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria, which was eventually taken to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and settled in 2002. Interestingly, both countries went to court citing not ancient tribal claims, nor the wishes of the present-day inhabitants, but colonial-era documents drawn up and signed by Europeans, when the British ruled Nigeria and Cameroon was part of the German Empire. These documents were the basis of the ICJ judgment stating that “sovereignty over the Bakassi Peninsula lies with Cameroon” and that “the boundary is delimited by the Anglo-German agreement of 11 March 1913.” The court noted that the boundary dispute “falls within an historical framework including partition by European powers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, League of Nations mandates, UN Trusteeships and the independence of the two states.”

Not all Nigerians are happy with the ICJ ruling, nor with their then government’s decision to abide by it. Some want the issue reopened. The Vanguard newspaper of the Niger Delta region has been campaigning for years to have the ruling reversed, and to revisit the case on the basis of ancestral land claims. One recent opinion piece ended, “To reclaim Bakassi Peninsula is a task that must be done!”

Academics argue about the extent to which the various disputes and conflicts are actually underpinned by ethnicity. Some suggest that politicians are just using the different factions to further their own aims. This may well sometimes be the case, but it does not mean that the differences are not there to be exploited, or that they do not run deep.

In some cases strong tribal affiliations can distract policy makers from focusing on what is in the national interest and can split politics along tribal lines. The relatively stable South African democracy, for example, is supposed to be ethnically blind, but the political system is splintered along ethnic and tribal lines: the Zulu are linked with the Inkatha Freedom Party, for instance, while the Xhosa dominate the ANC. The constitution of the country recognized these divides and set up Provincial Houses of Traditional Leaders in Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, Free State, Mpumalanga, and North West. They are in essence reflective of different South African “nations” or tribes.

Another political issue is that tribalism also encourages favoritism—or, to put it another way, corruption. This is a huge problem across the whole continent, described by Kenya’s former president Daniel arap Moi as a “cancer,” which impacts in all sorts of ways. Political appointments, business deals, and legal judgments can all be affected by it, which means the best person for the job is often not the person who gets it. It discourages marriage from outside a defined group, and it militates against national unity. It’s also hugely damaging for a country’s economic well-being. Funds that were intended for economic development, infrastructure, or any manner of public spending are diverted into the pockets of increasingly wealthy and powerful individuals. The UN estimates that corruption cheats the continent out of about $50 billion every year. Corruption occurs in every country in the world, but in Africa it is known to be particularly widespread. That’s why the African Union named 2018 the year for “Winning the Fight Against Corruption.”

On the other hand, some people have suggested that a number of checks and balances have been incorporated into the tribal systems, and that these can ensure a fairer distribution of wealth and power across a country. Nigeria, for example, as we’ve seen, has sharply delineated ethnic and religious divides. Many regions are overwhelmingly dominated by one group or another, and while the south of the country is predominantly Christian, the north is mostly Muslim. The south enjoys higher literacy rates, better health, and more money. The country’s political map runs along similar lines. The result is an unwritten rule to even out any discrimination or imbalance of power across the country as a whole: the presidency (which controls most of the budget) will alternate between a Christian and a Muslim. This is an example at the highest level, but many parliaments and governments make decisions taking into account the effect they will have on the country’s various tribes, with the aim of avoiding unrest and dissatisfaction. If the political parties representing tribes A, B, and C do not bear in mind the views of tribe D, they can expect trouble from that part of the country. This is similar to the workings of any other political system, but in Africa it is more tribally/ethnically based than most.

Some countries have had more success than others in limiting the political effects of these ethnic and tribal divisions. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, for example, outlawed parties based on tribal affinity, and in Ivory Coast Félix Houphouët-Boigny, president from 1960 to 1993, shared out power to a degree that kept a lid on regional tensions. Botswana has been relatively stable, partially because it is one of the few African states with a high degree of homogeneity, plus a democratic system and a functioning economy. Tanzania is another exception, despite having more than a hundred tribes. Its first president, Julius Nyerere, insisted that to forge a national identity the sole national language would be Swahili. Already widely used in the country, it became the glue that held together a nation. But even Tanzania is showing slight fractures: Islamists in Zanzibar are now calling for a referendum to end the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar that created Tanzania in 1964.

How much might tribalism affect the development of any country in which it has a strong hold? It is probably impossible to gauge accurately because we don’t have an example of a tribe-free country to use in comparison. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the need to constantly balance the competing claims of overlapping groups is a distraction from the development of the state as a single entity. When conflicts descend into violence, they can certainly destabilize an entire country, disrupt its economy, force millions from their homes, and cause millions of casualties. They can be incredibly costly, both to the country as a whole and to individual citizens, and they play a part in the terrible cycles of poverty and inequality that occur across the continent.

* * *

Africa is the poorest continent in the world. Globalization has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but the gap between the rich and the not rich has widened. The division is particularly stark in Africa, where seven of the ten most unequal countries are to be found. Across the continent are modern cities, rapidly filling with skyscrapers, multinational companies, and a growing middle class. But in all these burgeoning urban centers, alongside the wealthy live the incredibly poor, who might be scraping by on less than $2 a day. A World Bank study in 2016 found that the percentage of Africans living in poverty had declined from 56 percent in 1990 to 43 percent in 2012, but the number of people living in those conditions had actually increased from 280 million to 330 million due to the growth in population.

Zimbabwe is among the poorer countries in Africa, and large numbers of the population are intent on finding a better life elsewhere, especially in its two much wealthier neighbors—Botswana and South Africa—to the south. However, richer countries don’t necessarily want a huge influx of poor migrants, many of whom struggle to cross the borders. Botswana has a three-hundred-mile-long electric fence along its border with Zimbabwe. It says this is to stop the spread of foot-and-mouth disease in cattle, but unless Zimbabwean cows can do the high jump, it’s difficult to see why the fence needs to be so high. Zimbabwe, and its impoverished population, is also fenced off from South Africa. As one of the richest countries in southern Africa, South Africa is a magnet for migrants—which is partly why it also has a fence along its border with Mozambique.

Despite these barriers, many people do cross over into South Africa, and high levels of immigration have caused tensions just as they have elsewhere in the world. In 2017 Nigeria’s leadership appealed to the South African government to intervene to stop what it called “xenophobic attacks” during a spate of anti-immigrant violence, following comments reportedly made by the Zulu king, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu, that foreigners should “pack their bags” and go. He said he was misquoted, but the damage was done, and many of those rioting were heard chanting “The king has spoken.” The community of Zimbabweans, 3 million strong, was among the main targets, but around eight hundred thousand Nigerians are also in South Africa, and during the trouble no foreigner was safe if found by the mob. Nigerian homes and individuals were attacked, some Nigerian-owned small businesses were looted and burned, several people died, and hundreds of people were forced from their homes and fled to camps set up by the government. The trouble also led to anti–South African demonstrations in Nigeria in which South African businesses were attacked amid calls for South Africans to “go home.”

Here we see a scenario familiar in countries across the world: fear and anger directed at immigrants, who are not only accused of taking local jobs but also of creating higher levels of crime by selling drugs, forming gangs, and so on. Crime isn’t necessarily linked to immigration, but it is linked to poverty, and both are widespread across Africa. Statistics show that Africa is second only to the Americas in crime rates, especially murder. A UN report on global crime rates showed that of 437,000 murders in 2012, 36 percent were in the Americas and 31 percent in Africa. By comparison, just 5 percent of murders were committed in Europe. The same report suggested that in some parts of Africa the murder rate was increasing.

Poverty appears to be both a cause of crime and a consequence of it, and poor people are caught in this cycle. Most of those living desperate lives in shantytowns do not turn to crime despite lacking access to what better-off people would regard as the basics of a comfortable life. Nevertheless, they suffer the consequences of crime—theft, violence, weapons, gangs, drug selling, overstretched law enforcement, exploitation—all of which loop back into insecurity and underdevelopment and thus help sustain the poverty into which they were born.

While the poor are trapped in this cycle, the rich are getting richer and using their wealth to save themselves from experiencing the hardships of day-to-day poverty by retreating behind walls of their own: the gated community, a clear sign of the economic divisions and the vast inequality that can be found across Africa. Here are many attractions, as one advertisement makes clear: “Uncomplicate your life! Escape to Lusaka’s newest suburb. An exclusive and secure residential estate . . . MukaMunya is protected by an alarmed electric fence, a gated entrance and a 24-hour security system allowing entry by invitation only. . . . The main road is tarred too, making that dream of driving a low-slung executive car an option. Enjoy a host of facilities. . . . The park club house offers two tennis courts, a squash court, a 25-metre swimming pool and a fully stocked bar. In close proximity to one of Lusaka’s finest schools, the ‘equestrian belt’ and an easy drive into town.” The walls of a gated community promise luxury, safety, and exclusivity. If your name’s not on the list, you can’t come in, and to get on the list you have to pay. A lot. MukaMunya means “my place” in Soli, one of the Bantu languages of Zambia, but most of the local population can but dream of having a home there.

Fortified communities are not exactly new. From early agricultural times, on through the Roman period and the Middle Ages, walls around collections of dwellings were a normal way of living. Only in relatively recent times—with the rise of the nation-state and internal security, including police forces—did cities allow walls to be taken down or begin to expand outside them. Now the walls have started to go back up. But whereas in the past the whole community could retreat behind its walls for protection, now only a minority live behind walls permanently.

The trend for living in gated communities started to reemerge during the twentieth century and has been gathering pace ever since. Now such communities are being built across the length and breadth of Africa, with Zambia, South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria leading the way. South Africa pioneered the African gated trend. According to the Economist, as early as 2004 Johannesburg alone had three hundred enclosed neighborhoods and twenty security estates, while in 2015 Graça Machel, widow of Nelson Mandela, inaugurated the “parkland residence” Steyn City—a development four times the size of Monaco—which includes South Africa’s most expensive house.

This is not limited to Africa. In the USA, for example, the use of “fortified towns” seems to have begun in California in the 1930s with gated enclaves such as the Rolling Hills estate. Some scholars identify an acceleration in the building of gated communities in the 1980s and suggest that as governments cut back on welfare and spent less on communal areas the people who could afford to do so withdrew from the public space. One study in 1997 estimated that by then the USA had twenty thousand gated communities housing 3 million residents.

Similar patterns are clear in Latin America, which has also seen a dramatic rise in “fortress communities” this century. In Lima, Peru, what has become known as the Wall of Shame separates one of the wealthiest neighborhoods of the city from one of the poorest. Some gated communities have grown to be almost cities within cities—Alphaville in São Paulo, Brazil, for instance, houses more than thirty thousand—completely changing the way the urban centers operate and are organized. The Chinese are building developments far exceeding the scope of Alphaville.

This modern way of living is not only for the very rich either. The rapid growth of the middle class in many African countries has led to the development of gated developments marketed at those who cannot afford the luxury of a top-end detached house, but who can pay for a flat in a large compound of modern high-rise buildings. Take Nigeria, for example: in its capital, Lagos, which has a population of 21 million, you can find some of the world’s poorest people, living in the slums in floating shantytowns on the city’s lagoons, or crammed onto the islands around the mainland, close to multimillion-dollar mansions. In the new upmarket developments it is not unusual to see a two-bedroom apartment on the market for more than $1 million. You certainly wouldn’t get any change from a million if you bought in one of the developing new “cities” such as Eko Atlantic, which is built on just under four square miles of land reclaimed from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to Lagos. The city is ringed with such developments. They are a testament to the burgeoning middle and upper middle class of this oil-rich country of 186 million people, and how wealth distribution is changing in its urban areas.

The boom in such properties is partly a response to high crime rates, as we’ve seen. However, ironically, a 2014 study published in the Journal of Housing and the Built Environment suggested that moving to a house inside the “fortress” might actually increase your chances of a break-in. Anyone well-off enough to live in a gated community is assumed by burglars to have something worth stealing.

The 2014 study did acknowledge that the compounds offer levels of protection higher in general than those outside them, but said that they leave public spaces deserted and at higher risk of crime. Gated communities threaten to weaken social cohesion wherever they are built. The wealthy have always lived in certain parts of cities, but have shared social spaces, be they town squares, markets, parks, or entertainment areas that are open to everyone. The new model of urban and suburban living is designed to be exclusionary: you can only get to the town square if you can get through the security surrounding the town. This lack of interaction may shrink the sense of civic engagement, encourage groupthink among those on the inside, and lead to a psychological division, with poorer people left feeling like outsiders, as though they’ve been walled off. Increased wealth without bringing a relative degree of prosperity to all reinforces division.

Gated areas have consequences for the entire community and have further effects on attitudes to both local and national governments. If significant numbers of people live in communities in which they pay private companies to provide the infrastructure, such as water pipes and roads, and to protect them with private police and fire agencies, while dealing only with private health care, then the role of local and national government diminishes. And if a government’s remit is only to administer smaller sectors of society, then the cohesion of the nation-state is also weakened. It would be hard in this scenario for a politician to come up with the slogan Britain’s David Cameron used in 2016 in relation to financial hardships—“We’re all in it together.”

Or, to put it in the language of the United Nations in its UN-Habitat report: “Impacts of gating are seen in the real and potential spatial and social fragmentation of cities, leading to the diminished use and availability of public space and increased socioeconomic polarization. In this context, gating has been characterized as having counterintuitive impacts, even increasing crime and the fear of crime as the middle classes abandon public streets to the vulnerable poor, to street children and families, and to the offenders who prey on them.” However, some studies suggest that within the compounds gating has helped encourage a sense of social cohesion and community neighborhood that transcends tribe and ethnicity. This is where the tribal concept based on ethnicity breaks down.

In a 2015 study on gated communities in Ghana, when residents were asked why they had chosen to live in the developments, the top response was “quality homes,” with “safety and security” second and “class of residents” third. A “sense of community” was sixth, and a hint of the impact of gated communities on culture came in eighth: “a buffer from extended family system.” Although this reason came eighth, it was a fascinating insight into how this modern reinterpretation of a walled city will slowly contribute to the weakening of the close extended family ties found throughout the continent.

In places where welfare provided by the state is weak, and where employment is often temporary and informal, one or two relatively high-earning family members will normally use their income to help support dozens of extended-family members. Giving a family member a job is not considered nepotism but a family responsibility. This has long been the case in Africa, so putting a physical barrier between members of the extended family will have a negative effect as most of the properties built are for the nuclear, not the larger, family. The developments are a different world, and not just in the physical sense. For those on the inside, the new, much looser “tribe” is the social class of your immediate neighbors.

The new tribes living behind the walls identify with each other because they have things worth stealing, not because their mothers and fathers originally came from a certain region or spoke a particular language. They have similar lifestyles, often similar interests, which are similarly protected. When you have enough money, you can pay others to protect you; when you don’t, you band together, and so behind the walls the sense of “we” or “us” is diluted, sometimes to as little as “I.”

* * *

Ethnic identity still predominates in most African countries. While the nation-state borders are real—they exist within a legal framework and are sometimes marked by some sort of physical barrier—they do not always exist in the minds of people living within and around them. Like the Sahrawi, whose traditional territory has been split by the Moroccan Wall, many still feel the pull of their ancestral lands.

The postcolonial consensus by African leaders not to change the borders was based on a fear that to do so would invite never-ending conflict, and in the hope that they could build genuine nation-states and thus reduce ethnic divisions. It has been incredibly difficult, not least because in Africa the nations still frequently cross nation-state borders, whereas in, for example, Western Europe, clear geographical or linguistic lines more often mark where one nation-state ends and another begins.

We are now well into the twenty-first century, and Africa stands at a point that, with hindsight, was always coming: it needs to balance the rediscovery of its precolonial senses of nationhood with the realities of the current functioning nation-states. That’s a fine line, fraught with danger, but to ignore or deny the divisions that occur across the length and breadth of this vast space will not make them go away.

Once there was the “scramble for Africa”; now there is a race to bring about a degree of prosperity so that people may be persuaded to live peacefully together while simultaneously working on solutions where they wish to live apart.