CHAPTER 10

SPECULATION

ATLANTA WAS THE NEW Confederate nation’s turntable. The rebellious South had fewer than half as many miles of railroad track as the North, but a third of all lines traversing the Lower South, and just about all the 1,400 miles of track within Georgia, met up in the car shed. For thousands of soldiers, soon to be tens of thousands, and their equipment riding the rails from the Lower South to practically any front in the slowly developing continentwide civil war—Virginia, Tennessee, the Mississippi Valley and beyond, the Gulf or Atlantic coasts—the fastest route ran through Atlanta. The iron rails that gave birth to Atlanta also set the town’s factories and industrial workshops on a wartime fast track. The South had less than 20 percent of the Union’s industrial capacity. Atlanta’s industrial base had been created to service railroad needs and now offered a ready foundation for Southern military manufacturing. President Jefferson Davis’s military advisors urged him to move swiftly to put “the whole population and the whole production . . . on a war footing, where every institution is made auxiliary to war.” No place in the South was more prepared to benefit from a policy of total militarization.

Atlanta had long resisted secession, and few rejoiced at the prospect of civil war, but once it came, the city’s citizens rode a warhorse, and many thought they had picked a winner. Even before the first shots were fired, the Gate City offered up all it could to meet its new land’s military needs—and to boost the city into its next, explosive phase of growth. The Daily Intelligencer could soon boast with some merit, “Atlanta . . . is destined to be a great manufacturing city.” In their exuberant pursuit of that destiny, few in Atlanta suspected they might also be pursuing their own destruction.

“PERPETUAL MOTION DOES EXIST in this city, whose seal might well be a mammoth child directing a locomotive at full speed,” exclaimed an awed journalist on a visit from Columbia, South Carolina. Industrial fumes and the rhythmic clanging of ironworkers’ hammer blows blended with locomotive smoke and chugging engines as a steady and mounting flow of rich Georgia State and Confederate army contracts kept trackside factory forges blazing and machinery in motion: Win-ship’s Foundry and Machine Shop produced desperately needed freight cars and railroad supplies, along with bolts and plating for armoring ships; the Stewart and Austin flour mill produced hardtack troops came to curse; James McPherson’s match factory sold products to both army and civilians; numerous saddle and harness makers produced goods under government contract; Hunnicut and Bellingrath filled orders for alcohol, vinegar, and spirits of niter; High, Lewis, and Company distilled close to 80,000 gallons of liquor for the Confederate army annually; the Empire Manufacturing Company produced railroad cars and bar iron; a percussion cap factory opened in the first year of the war; W. F. Herring and Company and Lauishe and Purtrell Company turned out uniforms, knapsacks, and other cloth goods; gunsmiths milled and rifled gun barrels; the Peck and Day planing mill produced rifles and, without enough machinery and skilled mechanics to meet firearm requisitions, also contracted for 10,000 ten-foot-long medieval pikes; the foundries of Solomon and Withers Company forged brass and iron implements and “C.S.A.” belt buckles, spurs, and horse tack; the Confederate Iron and Brass Foundry also specialized in military accoutrements; and second only to the Tredegar Works in Richmond, the Atlanta, later the Confederate, Rolling Mill produced cannon, rails, and armor plate, including iron sheathing used on the Merrimac and other ironclads. The Atlanta Sword Manufactory turned out 170 finished swords for Confederate officers per week.

The Confederate army, too, set up its own operations in Atlanta. The general of the western Army of Tennessee, Braxton Bragg moved his Quartermaster Department’s headquarters here. In February 1862, he transferred the threatened Nashville arsenal to the buffered safety of Atlanta. Soon, thirteen separate shops were in production in scattered buildings, including a machine works, arsenal, and tannery. Munitions laboratories went up at the old fair grounds racetrack, where many of the nearly 5,500 yellow-skinned arsenal men and women—more than the entire town’s population less than a decade earlier—hunched over benches, packing percussion caps and artillery and small-arms ammunition, as many as 25,000 rounds and 150 artillery shells per day by August 1862, eventually churning out 23 million musket and pistol caps and 4.1 million rounds of small-arms ammunition. The Army of Tennessee’s Quartermaster Department employed a small army of some 3,000 “needle women,” or seamstresses, most hauling home heavy bolts of flannel to sew into jackets, pants, and shirts. One hundred cobblers in a government shoe factory turned out as many as five hundred pairs of boots a day on those rare days when enough leather could be secured.

In the wartime frenzy, houses and barns became workrooms and factories, making it “impossible to detail at this time the numerous establishments for manufacturing purposes in Atlanta,” noted the visitor from Columbia. “They are daily increasing.” At her Marietta Street home, a young Sarah Huff watched in astonishment not only as the men in her life departed but as “the wheels of industry, the spinning wheel, the reel and the winding blades moved swiftly in my mother’s wartime household,” as they, too, began producing clothing, tents, blankets, and uniforms. Much like everywhere in town, “decided changes . . . [took] place very early in the war,” and her neighborhood filled with workers and their machines. “Right there in sight of us,” her industrious Scots neighbors built “a factory [that became] . . . the most extensive button factory in the south.” She and her friends looked through the doorway in awe at the “wonderful sight” of powerful cutting machines banging out thousands of cow-bone buttons for soldiers’ uniforms.

AN UP-COUNTRY TOWN not to be found on a map fifteen years earlier soon became the South’s second most important war materiel production center, after Richmond itself, where Jefferson Davis moved the Confederacy’s capital in May 1861 as a direct affront to nearby Washington, D.C. To many minds, given Atlanta’s location in the heart of the rebellious states, its importance exceeded even the capital city’s. Few people in the North or among Union military officials had heard of Atlanta before the outbreak of the rebellion, but most soon recognized that “the Citadel of the Confederacy” lay nestled beyond the fastness of the lower Alleghany ridges and hills. On distant battlefields, Union soldiers began to make mental note of the “Atlanta” stamped on captured Confederate wagons, artillery pieces, and ammunition boxes—calling cards from the Gate City. The Yankees would remember the name of the town as they marched south.

TO HELP KEEP ATLANTA’S Confederate engine and hub of war making on track, Mayor Jared Whitaker resigned his office in late November 1861 to become commissary general for the Georgia State army, setting up his headquarters downtown. City councilman Thomas Lowe filled in for Whitaker for the month and a half before the next election. With nearly all hope for a brief war dashed and the conflict assuming an all-consuming gravity and awesome violence, in January the electorate jettisoned political ideology and turned to a steadying and moderating hand to guide the town. James Calhoun remained perhaps the best-known Atlanta citizen opposed to secession. Moreover, he had never turned his back on friends or professional associates who had remained avowed Unionists and, in some cases, been harassed and even attacked as traitors. His own politics, though, were now in alignment with the needs of his regional home. Said his son Patrick Henry, his father still “thought that our differences should be settled peaceably, and not by war.” But the war had come, and though his father would later contend that he, too, had remained a Unionist all along, his youngest son insisted, “There was no better Confederate than he.”

In running for City Hall, he benefited from swiftly changed voter demographics. Many of the men eligible to cast ballots, including many of the most militant secessionists, had already departed for military service. The electorate left in town comprised primarily older and wealthier men more likely to favor the fifty-year-old Calhoun’s good government and pragmatic brand of politics. He won the election, handily defeating T. L. Thomas by 530 to 256 votes for his first one-year term in office.

In stepping into his City Hall office, Calhoun faced a burgeoning and unprecedented set of challenges, perhaps more daunting than those faced by any American mayor ever, to govern his still-young municipality. All that expanded and new industry brought jobs. Jobs and the Union army nibbling sharply at the slave states’ frontiers brought new people to town in droves. The population doubled in a year to fill the needs of the factories and shops. Refugees and wounded soldiers arrived by the thousands. A backwoods railroad transfer stop and regional market town instantly became a substantial small city, the fourth largest in the Lower South, after only New Orleans, Charleston, and Mobile. While most towns diminished in the face of Yankee threats, Atlanta just grew and grew.

Those who knew Atlanta best found it practically unrecognizable from prewar days. Observed one frequent longtime visitor a little over a year after the war began, “The car shed was there, the people were there. . . . The faces I had usually met were no longer visible, but strange people in strange costumes met me at every corner.” Another visitor watched as “all day long and even during night, it is ‘clang, clang, clang,’ as the cars arrive or depart—filled to their utmost capacity with the crowd of floating population going somewhere, or returning from that direction.” This mounting tide of opportunity and need overwhelmed every aspect of town services. Thrust into its leadership, Calhoun worked to keep Atlanta functioning, believing that City Hall should do all it could to ameliorate conditions. He was soon forced to manage the city with little help from the city council as more than half its members shortly resigned to enter military service.

At home, his life was merely an extension of his day’s labors. Calhoun’s law partner and son, William Lowndes, watched the heavy traffic of men passing through their Washington Street house. He would shortly depart for the army, but while still living in his father’s house, Lowndes recalled “scarcely a day or night that it was not visited either by confederate officers, civil officers or citizens, and many times wounded and sick soldiers were cared for therein.”

ALL THOSE OLDER, wealthier Atlanta citizens, refugees arriving daily, skilled railroad mechanics and others exempted from military service, needle women with their meager earnings, thousands of convalescing soldiers well enough to walk around, and troops in transit or on leave carried more or less cash with them. They made ready customers for the Five Points’ profit-sniffing merchants. The shopkeepers of Whitehall, Alabama, and Peachtree streets, too, saw war as a chance to expand their businesses like never before. With Northern manufactures no longer to be had, shopkeepers needed to extend their reach to find goods to sell this vast new clientele. Atlanta, along with the rest of the South, would have to shrug off any lingering provincialism to become an international city. The local chamber of commerce traveled far beyond the South, dispatching representatives across the Atlantic to find new trading partners, and forwarded weekly editions of local newspapers to European manufacturing cities with ads for local importers.

In the early fall of 1861, the chamber addressed a boosterish circular to its London counterpart in which the pint-size city’s merchants audaciously proclaimed their hometown, symbolically “located upon a granite or primary formation at a high elevation” and standing at “the geographical centre of the new Confederacy,” now rivaled New York City. The Gate City opened its doors wide to new trading partners, while, declared the chamber, the great Northern metropolis and trading hub was “from various causes already becoming inoperative.” Blithely ignoring the federal naval blockade of the entire southern seaboard, Atlanta merchants invited English producers to ship their goods without fear or tariff. “Our whole coast is thus open to the commerce of the world.”

When the New York Times’ editors read the Atlanta pamphlet, they sneered at “the ridiculous cockerel circular of a Chamber of Commerce of a little wooden village in Georgia.” But the Gate City put potential business partners on notice that it “want[ed] the freest possible trade with all the world.”

Atlanta aimed to become a world trading hub for the new Confederacy, and wealthy Atlantans wanted to profit from that overseas trade. Leading city merchant partners Sidney Root and John Beach secured Atlanta’s largest interest in the trade by establishing a large fleet of ships and a port warehouse in Charleston. Beach moved to England, where he set up a prominent import-export office in Liver-pool. Soon the Root & Beach firm had as many as twenty-one steamers running at any one time. Besides their warehouse in Charleston, Root & Beach had eleven in Atlanta. Other Atlantans envied their enormous profits. “Almost everybody who had any money was anxious to go into a blockade company,” recalled Amherst Stone, who would soon leave the city and his wife, Cyrena, behind in hopes of acquiring a ship to bring “considerable cotton” out for trade. Scheming to put his northern contacts to use, he collected tens of thousands of dollars from business associates to finance a move north, where he hoped to win official permission to bring cotton to the Union. He quickly found himself locked up in a prison in the New York Harbor.

Root & Beach ships got through the blockade often enough, and as a result of ships eluding the blockade, by the summer of 1862, the Southern Confederacy reported, as much from aspiration as fact, “our own city is getting to be full of English goods.” Traders overseas appeared eager to expand their entry into the Southern market. Before secession, most trade passed through Northern ports before making its way south. “Soon,” crowed the Confederacy, “we shall have plenty of English goods here, which have not been polluted by the touch of Yankee fingers, and which have not greased their palms in passing through; but they will have come direct to us from England.” The present “sufferings, inconveniences and privations” boded well for the future of an independent and self-sufficient Southern republic. “The blockade and the high price for goods have accomplished, and will accomplish, more for us to introduce and establish direct trade than twenty years of diplomacy.”

IN THE EARLY MONTHS of the war, the

New York Times could still disparage “the great centropolitan Atlanta,” which it dared “Mr. Bull” to find on the map “if the stupid chartographer has not left it out.” But by the end of the second year of fighting, the

Times needed to acknowledge a new center of gravity in the rebellious states. The newspaper reported,

Atlanta is really the heart of the Southern States and therefore the most vital point in the so-called Confederate States. [The region’s towns] manufacture one-third of the horseshoes, guns and munitions of war made in the South. The machinery for the production of small arms has been taken to Atlanta, which place has extensive foundries. . . . Besides it is a flourishing city, an important railway centre, and extensive depot for Confederate commissary stores. Atlanta to the South, is Chicago to the Northwest, and its occupation by the soldiers of the Union would be virtually snapping the backbone of the rebellion.

Yankee boots marching on distant battlefields remained far from the Confederacy’s industrial and commercial heart, but strategic planners considered it a future target.

THE CONFEDERATE SUPERINTENDENT of armories, Lt. Col. James Henry Burton, was drawn to Atlanta, or so he thought when he came looking to secure a site to build his massive new armory for manufacturing Enfield model rifles in the summer of 1862. He was dismayed by the reception he received. The land was “so broken and rolling” that finding even “an acre of perfectly level ground” proved nearly impossible. He finally chose the old racetrack as the best spot, next to the fair grounds where the arsenal’s munitions laboratory buildings were going up. The property’s absentee owner was renting the site for the labs. He was willing to sell land for the new armory outright to Burton and the Confederacy, but, as a journalist noted, “the value of property [was] advancing with railroad velocity.” The land’s owner knew the value would only increase with time. He asked $15,000 for fewer than fifty acres, at least a twentyfold markup over the prewar rate for land outside the city limits.

Burton might have negotiated further but ultimately felt rebuffed by “the prevailing feeling of the people of this place generally towards the Govt.” Atlanta, he discerned, was in the Confederacy but not entirely of the Confederacy. City council officials delegated to assist him met his offer to build one of the largest industrial enterprises—and one most vital to Confederate military success—with “indifference.” He angrily concluded, “Speculation in real estate seems to be the sole object in view by the citizens of this place.” Business was booming.

Fortunately, other, less prosperous inland Georgia towns were more than happy to take what Atlanta spurned. Macon’s town fathers offered him “a free gift” of “an ideally suited” thirty-acre tract of land. “The citizens of Macon are most anxious for the location of the Armory at that place . . . whilst quite the contrary seems to be the prevailing sentiment here.” Burton chose Macon. “Now,” he scolded his hosts, “here is a good opportunity of accomplishing, without cost, what it seems I cannot accomplish at this place at any cost.” He saw little chance for Atlanta to become “a thriving place” in the new nation without a change of heart. He could only shake his head. “I am disappointed in Atlanta,” he wrote the Confederate chief of ordnance in Richmond.

OTHER VISITORS TO ATLANTA may have shared Burton’s discomfort with the town’s money-first attitudes, but few shared his predictions for its future. A Tennessee reporter surveyed the Five Points not long after Burton gladly left for Macon. He observed many of the same traits Burton did but from a different perspective. War had not changed the town; Atlanta had merely become more of what it had always been. The Tennessee journalist reported,

I strolled up the streets, and there was the same hurly-burly confusion of business-men as heretofore. Everybody wanted money—everybody made money. The Jew and the Gentile were found whispering together for a bargain. The milliner declared that ‘this cannot be bought elsewhere for less than such a price.’ The auctioneer from the stand was astonished as usual that his crowd would not bid more for this article, as the stores would charge double what they were bidding. Brokers had gold and bills scattered profusely upon their counters, ready to give you as clean a shave as any one of the many barbers that line the principal streets. . . . The engines whistled, cars were shifted hither and thither, and people passed the crossing as usual without being run over. I concluded that Atlanta, in point of business, was unchangeable, and that she has felt the shock of war less than any of her sister cities.

By contrast, many other Southern cities and towns withered. On a stopover in the Black Belt market town of Americus a few months later on, book and paper goods seller Samuel Richards found the once thriving Sumter County seat “dried up, the stores nearly all closed and most of the men gone to the war or somewhere else.”

Prior to the war’s advent, Richards had fretted in his languishing hometown of Macon. Even the prospect of the massive new armory’s construction gave him little cause for optimism. Meanwhile, his brother Jabez had all he could do to handle customers at their Atlanta store. Those in Samuel Richards’s Macon circle who knew Atlanta were “much pleased with it,” he noted; the city was “no doubt a more healthy and salubrious place than Macon.” It was also a healthier place to do business in those days. With “our stocks . . . decreasing and the prospect of supply very unpromising,” Samuel Richards finally packed up the Macon store and closed up his house on the first day of October 1861. He crowded his wife and three children, including a new baby, and all their possessions into two rooms in his brother’s small place off Washington Street.

It was an auspicious moment for him to move on. The Confederate Congress had just confiscated all Northern goods and debt. The $5,000 the brothers owed Northern wholesalers for purchases on credit “will never reach the hands of those to whom we owe it.” Among his creditors was his “fanatical” and “renegade” older brother William, gone north in location and outlook. He, too, would have to lose out. Shrugged Richards, “We shall have to treat our brother William as we do other ‘alien enemies.’” In fact, he lamented, “What I most regret in his case is that he is an alien enemy.”

Once in Atlanta, Richards found that business was good, very good indeed. On the last day of 1861, he noted that the brothers’ stock was “getting low in quantity but pretty high in price!” With paper goods growing scarce—and families corresponding more than ever with their far-flung soldiers—Richards wished only that their stores carried exclusively difficult-to-source “paper and envelopes. We could make a small fortune out of it.” Less than a year after Samuel Richards’s arrival, the brothers’ “profits [continued to be] splendid.” Though some sales did not exactly enrich them—for instance, “for books in general we only get double former prices”—others brought astronomical gains. “Some of our profits are enormous truly,” he recorded when well settled in Atlanta. “Today Jabez sold a bill of pens & holders for $28 which cost originally 75¢!”

Before long, “money,” he celebrated, “comes in so fast that we hardly know how to dispose of it to advantage.” With their business earnings and the thousands of dollars they saved when the rebel government wiped out their debts to Northern creditors, the Richards brothers joined the investor class in town. They bought several building plots and houses within and just beyond the city limits. They diversified, backing a shoemaking shop, putting a couple thousand dollars into Amherst Stone’s ill-fated blockade-running scheme and a thousand more into the Confederate Insurance Company, briefly operating a grocery store until shortages caused them to sell out, and acquiring a religious-tract printing house. Jabez also bought several bondsmen for household servants and to work a farm he purchased outside town.

Finally, Samuel, now an ardent secessionist who “rejoiced[ed] to hear that our invading cruel foes are being destroyed,” achieved a long-standing milestone of his own: He “committed the unpardonable sin of the Abolitionists in buying a negro.” For the past two years, he could afford only to hire the time of Ellen, a slave girl “13 years old, healthy and ugly,” whom the family brought with them from Macon. With his newfound wealth, he drove a hard bargain before concluding a deal with her former Macon owner, buying her for $1,225, “$275 less than [he] priced her at three months ago,” Samuel gloated. He was satisfied he had purchased “a pretty good girl,” but he ignored the “good whipping” he had lately given her after catching her using his wife’s “toilet articles.” It wasn’t the first time he had beaten her; nor was it the last. A few months later, he took a lash to her again, this time for a spool of thread missing from his wife’s drawer “and other misdemeanors.” Despite such transgressions, he believed her to be worth nearly double what he had paid, and expecting “when we come to a successful end to this war that negroes will command very high prices,” he purchased another entire slave family.

THE MONTH BEFORE ELLEN became a chattel member of the Richards household, his infant daughter Alice got terribly sick. The benefits of Atlanta’s “salubrious” climate proved short-lived. The city’s small-town sanitation system struggled to support its swelling citizenry as well as the people passing through by the tens of thousands. Privies overflowed; people relieved themselves in open toilets; army horses hauling supplies and men added to the fouled water supplies. Mayor Calhoun’s court began issuing fines for owners of privies the Board of Health deemed in an “unfit condition,” and the city council hired laborers to “put in healthy condition all privies used by the Authority of the Confederate States of America.” The city government sold lime for privy use at cost to residents, though the supply was so limited that there wasn’t enough to blunt the stench or contain the swarms of flies.

A physician diagnosed Alice with cholera infantum, a catch-all term for a childhood gastrointestinal disorder accompanied by fever, but she likely had typhoid fever, a diarrheal disease, increasingly common among warring troops and in overcrowded urban areas, spread through feces-polluted drinking water. The child lingered for a painful week before the disease wasted her away. “Distressed and troubled,” Richards found, “one thing however gave me some comfort.” He was desperate to avoid being called up for military service. A local printing shop was on the verge of hiring him, giving him one of the few jobs the Confederate government considered crucial enough to “exempt me from conscription.”

He recorded shortly before the first anniversary of his move to Atlanta, “Our sales continue good and our profits also good.” But he also admitted, “I would willingly go back to old trade and moderate profits if we could only have peace and independence. We live now in a state of feverish excitement and disgust that gain cannot render bearable or desirable.”

AT LEAST RICHARDS HAD his gains. Many citizens had only the “feverish excitement and disgust.” The porous and wavering boundary between loyal and rebellious states and the enduring need for Southern cotton in the North encouraged extensive quasilegal trade via Memphis and other Mississippi River cities until mid-1862. Finally, due to hardening army and governmental outlooks about commerce between the warring sides, coupled with Yankee military successes in the West, nearly all shipments of western crops into the South were cut off. The lack of rolling stock and the government demand for the rail lines also sharply curtailed food reaching Atlanta. Less than a year after the taking of Fort Sumter, shipments into the city of flour, hogs, sheep, and corn had declined between 30 and 80 percent from what they had been in 1860—while the population had more than doubled.

In addition, the Confederate army began seizing farmers’ harvests for the military. The Richmond government passed an impressment statute, requiring farmers to turn over to the government 10 percent of everything they raised, from livestock and grain to vegetables, tobacco, and cotton. Impressment agents, accompanied by armed soldiers, confiscated their 10 percent levy and very often took anything else they wanted. When the woman of the Atlanta Hospital Association tried to sell sugar to finance an “invalid ladies” home, the Confederate army impressed the sugar. The roving government officials—and bandits masquerading as Confederate authorities—commandeered farm wagons traveling to Atlanta, with promissory notes for future payment in return. With the army impressing civilian property and thieves ready to make off with anything not tied down, Atlantans started hiding their most valuable items, even going so far as to bring their horses and buggies up the steps and into the house. When the Army of Tennessee ran desperately short of shoes, leaving much of the army to march barefoot in the frozen hills, General Bragg seized every boot in town not being worn. Citizens howled at the confiscations by “high officials who set the example of lawlessness by appropriating what did not belong to them,” in the words of a Southern Confederacy correspondent.

Afraid of further confiscations, farmers squirreled away their harvests in bulging granaries and corncribs and stayed clear of the roads and Atlanta’s markets. Mayor Calhoun wrote to Confederate president Davis about the legality of such seizures and to what extent the city could expect to face continued impressments. Davis replied that the practices were indeed legal. He offered to investigate unauthorized seizures—to no effect.

WITH BASICS IN SHORT SUPPLY, inflation spiraled out of control. By December 1862, the wholesale price index in the South had increased seven times above that of the heady days of spring 1861. Contributing to the inflationary spiral, the counterfeiting of so-called shinplasters—illegal currency issued by private corporations and individuals after silver change disappeared from circulation—and Confederate dollars was rampant. Numerous deals fell apart after currency and notes proved worthless paper. Jabez Richards discovered that $1,000 in cash he’d put up in partial payment for a slave were counterfeit, forcing him to fight against returning the slave to the previous owner. The Fulton County Superior Court tried 136 counterfeiters in a single year. Few issuing false notes were ever apprehended. In the summer of 1862, the Southern Confederacy reported that illegal shinplasters were “as thick as the frogs and lice of Egypt.”

The Richmond government added fuel to the inflationary fire by printing government paper as quickly as its presses could operate, without any backing except a promise to redeem it at face value two years after the war. Prices stepped up and up, reaching a 12 percent per month rate of increase by the end of 1861. A bag of salt costing $2 before the war went for $60 in the fall of 1862. Goods were “changing hands,” reported the Southern Confederacy in early 1863, but only “at big figures that are unquotable.” Soon a street laborer could earn $2.50 a day, the pay for a skilled laborer before the war, but that was still a starvation wage. Eventually, inflation soared to ninety-two times prewar prices, the highest rate in American history.

Cyrena Stone recorded prices from her account book “for the amusement of future generations.” They would remain the highest ever paid for such goods. A pound of pepper cost $10; a ham, $54; four pounds of butter, $40; fifty pounds of coffee, $500; a Merino (wool) dress, $400; “a green silk ‘love of a bonnet,’ with pansies & plums $150.” She concluded, “No purse is large enough to hold all the ‘needful’ that is needed to make more than one purchase.”

The once thriving newspapers began to look threadbare themselves. Merchants found little cause to promote the goods they had for sale, other than tobacco, corn whiskey, and slaves. A few ads boasted of the arrival of European goods by blockade runners via Nassau. Numerous ads called for the apprehension of runaway slaves and army deserters—all described and named. Long lists of the wounded filled columns, as did lists of those who had distinguished themselves in battle. Some notices detailed captured slaves brought to jail and waiting for their owners to pick them up. The occasional house or land was offered for sale. Many more ads solicited housing. Owners needing cash put up household items for sale, especially pianos. Publishers themselves were forced to scramble to find sufficient newsprint and ink for their runs, eventually resorting to printing issues on half sheets and even wallpaper.

POVERTY STRUCK WOMEN, whose men were gone to war, hardest. Gaunt mothers dressed in burlap came to Cyrena Stone’s Houston Street door everyday, seeking sewing or begging for food. One evening three barefoot women came by, their husbands having long since departed for war, all now left destitute. Stone recorded, “They said their rich neighbors persuaded their husbands to volunteer in the first war [sic], promising that their families should never suffer. But the promise was forgotten, & the little sewing they could get, hardly kept them alive.” Each woman beseeched her aid with “the same cry—‘How can I get bread for my children!’” Another mother of five children stopped at her house on her two-mile walk to the Army of Tennessee’s Quartermaster Department to take home government sewing, at the going rate of $1 for a pair of pants, $1.50 for a coat, and 50 cents for shirts. According to Stone, she at least did not have far to go for the work. “Many a woman walks eight or ten miles to town to get sewing.” This woman “was so delighted” to show her sympathetic friend the new pair of shoes “she had been sewing for months to get.” The well-to-do secret Yankee Stone did not suffer so, but she wondered, “Is it any marvel that crime and prostitution are so common?”

Newspapers published advice on ways a woman like Cyrena Stone could make do without her past luxuries. These included recipes for brewing coffee out of beets or sweet potatoes—“those who give it a fair trial will be unwilling to go back even to the best Java.” To the fashion-minded lady, the Southern Confederacy suggested, “You can cut up your last fall dresses, and out of the skirts make the children nice new dresses; and, rather than miss doing a good thing, you can wear some of them yourself this fall and winter. You can ‘take in’ your hoops (to suit the hard times—shorten sail in this storm) and save several yards in making a new dress for yourself. There are a thousand little plans which a thrifty house-wife can adopt to save money, and look well too.”

ATLANTA’S FAST-GROWING and transient population, exceptional access to goods through its superior transportation network, and wealth from manufacturing made conditions ripe for a speculative economy. Its individualistic, get-ahead commercial spirit drove men to seek quick profits—sometimes at the expense of neighbor and nation. “Atlanta,” complained John Steele, who took over from Jared Whitaker as editor, in the Intelligencer, “is now made headquarters for itinerant speculators in gold, bank notes, Confederate currency, meat and bread.” An Alabama soldier’s wife, Mrs. Wellborn, watched store-keepers stash inventory under counters “to get it out of reach of the city authorities” to be sold later at a higher price. Such practices demoralized people who could ill afford the higher prices and led Steele to proclaim, “These men are greater enemies to the Southern cause than the foe in the field.”

Many in Atlanta resented the traders they branded as speculators. Those who drew some of the sharpest rebukes were erstwhile slaves. One of the most enterprising traders in the city came from the sixty skilled bondsmen on the Ephraim Ponder estate on the outskirts of town. All of the Ponders’ slaves were more or less free to contract out their labor. Several took advantage to pursue opportunities denied to nearly all other slaves. A few saved up enough to become traders. Little held them back after their master left his wife, Ellen, alone on their big estate. Fourteen years her husband’s junior, Ellen had long been admired as “beautiful, accomplished, and wealthy.” Ephraim was devoted to her and trusted her enough that “in consideration for the great love and affection he bore,” he placed his entire estate, including his slaves worth an estimated $45,000, in trust for her. He came to regret his generosity.

Not long after the couple moved to their new Atlanta home, scandal rocked the household. Others had long whispered about his wife’s “dissolute” ways and frequent adulterous liaisons, but Ephraim did not learn of them until 1861. Ellen, he declared in his divorce deposition, had been cheating on him at least since 1854. He accused her of being unable to refrain from “illegitimate pleasures,” drunkenness, abusive language, and the “utmost disrespect,” even threatening him with a gun.

While the shocking divorce proceedings dragged on, Ephraim, “brokenhearted,” left Ellen to live alone at their beautiful Atlanta dream estate and returned to Thomasville. Alone in her house, the chatelaine’s “only thought or care was to remember when [her slaves’] wages became due and then to receive it,” recalled her most trusted slave, Festus Flipper’s young son Henry, who grew up in the teeming Ponder slave quarters. After the master’s departure, Henry recalled his childhood in the midst of slavery being “virtually free.” With no white overseer on the estate, he and the other young children even began to receive reading lessons from another slave on the property.

Henry’s cobbler father and the other men and women living on the estate hired out their time in town. One Ponder slave, Prince Ponder, a wainwright by training, tried to ply his craft, but the local white mechanics resented the competition and would not let him practice his trade. He saw other opportunities in the war for a black man. Although subject to harassment by the patrollers, he had his mistress’s written permission to travel and trade “anywhere” in Georgia. With some savings, he took the risk of buying and selling “on anything there was any money in.” He made some money, speculated in gold as Confederate money lost its value, and with the profits bought more items to sell. Soon he had enough to rent a house in Atlanta, which he used as a warehouse, and opened a grocery store where he sold corn, rye, hops, flour, bacon, whisky, tobacco, boot leather, and “anything else,” he said, “on which I could make any money.” He moved his wife and children to a farm outside of town belonging to his friend, the wealthy Unionist builder Julius Hayden. He even lent money to Hayden at times.

The underground economy open to anyone daring enough, even a slave, proved astoundingly lucrative in a time of scarcity. Though he may have exaggerated his success in accumulating money, Prince Ponder claimed he “often” took in $5,000 to $6,000 in a single day. He estimated that while still a slave, he earned a total of $100,000 in inflated Confederate currency and had as much as $50,000 tucked away at any one time. Inflated money or not, he was as wealthy as some of the richest men in town. He purchased a pair of mules, two horses, a buggy, and a wagon. He had cows, hogs, and poultry. Each month, he made his way back to the Ponder place to turn over a few dollars to Mrs. Ponder. In return for his freedom to hire out his time, he at first paid her $40 per month. As the war continued, his rent coming back to her eventually reached $100 monthly. She had no idea how much money he was making for himself.

Prince Ponder invested some of his money in gold, likely purchased from his friend and fellow slave-entrepreneur Bob Yancey. In his barbershop and out of his Houston Street house, Yancey, too, traded in anything he could move at a profit. He continued to loan money to gamblers but also bought Yankee dollars and bits of gold, often purchasing them from Union prisoners he met when he went into hospitals or when they were in transit through Atlanta on their way to the Andersonville Prison. The army guards paid little attention to him, a barber and slave, while he shaved Yankee prisoners. That gave him time to dicker over the price of greenbacks, the Yankee paper currency; the Union men in turn hoped to use Confederate dollars to escape. Yancey then went into the Confederate barracks where he shaved rebel soldiers’ beards and exchanged Confederate money in return for prized Northern currency.

Yancey showed the Unionist industrialist William Markham two thousand-dollar bills he’d purchased from Yankee prisoners for $8,000 in Confederate money. He turned around and sold those U.S. dollars at a rate reaching three hundred Confederate dollars to one green-back, “though,” noted a Confederate deputy provost marshal who had tried to stop him, “it was a dangerous thing for a man to do.” The Confederate Congress made dealing in greenbacks a crime punishable by up to three years in jail and a $20,000 fine. Few thought of the possibility that blacks could be among the most prosperous of the moneychangers, and the law did not provide additional penalties for slaves or other blacks caught dealing in greenbacks. According to one local white businessman, Yancey was “about one of the biggest traders we had here,” white or black.

Atlanta seemed unable to contain the growing population of slaves in town who lived in a state bordering upon freedom. John Steele of the

Intelligencer was no friend of the mayor, John Calhoun, and accused him of ignoring laws governing slave labor and conduct. In a long list of shortcomings he hoped to see corrected during the Calhoun administration, Steele editorialized,

The next thing desired is to stop this habit of negroes hiring their time and making contracts with white men for the performance of work and charging the most exorbitant prices they can think of. Such conduct is against the laws of the State and should be severely punished. It is absolutely shameful to see the liberties that negroes are taking in this city. . . . If the negro slaves of this city are to be allowed their own way and to continue in the same course they have been hitherto pursuing, we shall very soon have the same abolition curse that caused this war, started in the State. Slaves should be treated as such and not allowed the rights and privileges of white men, and we shall insist that if any responsible white man gives information of any violation of the laws respecting slaves that Mr. Calhoun will listen to the charge and promptly investigate it, without thinking such an act on his part a disgrace to his magisterial dignity. He was put there to do it and he has a right to attend to it.

THE MAYOR AND OTHER ATLANTA officials tried without success to rein in speculators of all colors. They had few tools at their disposal. The DeKalb County grand jury, which in addition to its judicial role acted as a kind of citizen’s council, blamed “the unnatural and implacable war waged against us by the North” for “the scarcity of money and the enormous high price of the necessaries of life.” But the “enemies without” were “enhanced by enemies within.” The jury sent a message calling upon the state legislature to apply its powers against “those capitalists who are using their means to speculate and reap immense profits upon the necessaries of life.” The Georgia General Assembly quickly criminalized speculation, but the laws were easily circumvented and rarely enforced.

With resentment building against Atlantans “riding in their four-thousand-dollar carriages, dressed in thousand-dollar silks and two-thousand-dollar cloaks, and at night attending the theatre or joining in the dance[s],” simmering anger at speculators inevitably boiled over into violence. An Atlanta woman racing through town in a buggy ran over what she thought to be a soldier. She pulled up in horror and turned back to look at the prostrate man. When she recognized him as an “extortioner,” she whipped her horse on, “regretting that her buggy wheels had not run over his neck.”

Food thefts were rampant in Atlanta. Cows and chickens, even vegetables and fruit, disappeared from family plots. Whitaker reported burglars struck his Commissary Department’s food warehouses so often, they had depleted his inventory—mostly of bacon—to almost nothing. Police did not bother to investigate robberies of private gardens and livestock, as well as of household goods and tools, so many were reported. Citizens stopped bothering the city marshals with their troubles.

In a notorious incident that made headlines even in the North, a dozen or so women barged into a Whitehall Street store on a late winter mid-afternoon in 1863. “A tall lady on whose countenance rested care and determination,” according to newspaper reports, asked the clerk the price for bacon. He answered $1.10 per pound. The woman told him she and the others were wives and daughters of soldiers. They could not afford that price and wanted the government price for bacon. The grocer refused. At that, she drew “from her bosom a long navy repeater, and at the same time ordered the others in the crowd to help themselves to what they liked.” The women walked away with nearly $200 worth of bacon.

Many people in town stood up for the “mob of ladies.” The Intelligencer ’s portly, fire-eating editor, John Steele, intoned that the “scene moved the sympathies of his soul.” But in a follow-up to the incident, his leading daily rival’s editor, the now hardnosed Confederate G.W. Adair, was not so sympathetic in the pages of the Southern Confederacy . He insisted that these were no starving wives and daughters of soldiers but greedy exploiters of public sympathy for personal gain. “The tall female with determination in her eye, and who had elicited so much sympathy as the ‘boss’ of the seizing crowd, is the wife of a shoe-maker in this city who had not been to the army and is receiving very high wages for his labor, and in comfortable circumstances.” The identities of the ladies involved were never fully resolved. Perhaps for fear of arousing further public ire, none of the women was arrested. The Confederacy urged any truly hungry women thinking of following their example to “let their wants be known—if they will go to the Clerk of the Council and register their names and place of residence their wants will be supplied.”

Despite such claims about the ready availability of charitable and public assistance, Calhoun’s city government in fact could do precious little to meet the citizens’ needs. At $4,062.67 in 1862, the city budget for relief for the poor was the third largest item behind city salaries and street and bridge repairs. In the next year, relief for soldiers and aid to the poor had become the city’s single largest expenditure, at $16,200 for the year. But with inflation jumping manyfold faster and the number of indigent people increasing daily, that amount was nowhere near enough. Calhoun’s government did what it could to alleviate the spreading misery. “In view of the almost impossibility of procuring the necessaries of life, food & fuel,” the city council set up a committee chaired by the mayor “to devise a plan by which such articles shall be furnished at their cost when distributed.” Calhoun tried, with rare success, to jaw merchants into holding their prices down or even donating or selling at cost basic foodstuffs. One grocer donated 1,000 pounds of rice to the needy to much acclaim; salt donations were made to stem the cries of “salt famine.” The Intelligencer ’s John Steele called on City Hall to open Atlanta’s treasury “to purchase large supplies of fuel to be held for the use of those who will be unable to pay the high prices for fuel demanded.” With the winter of 1863 approaching, the mayor persuaded the railroads to carry firewood from the countryside free of charge to distribute to the poor. Only a few sticks ever made it to the cold hearths of the needy.

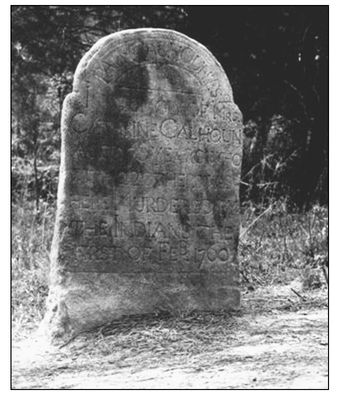

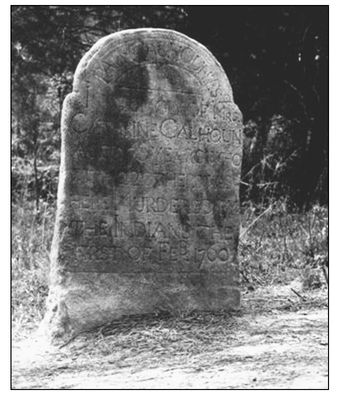

1760 Long Cane Creek Massacre Stone

at the South Carolina site where

Indians attacked Calhoun settlers

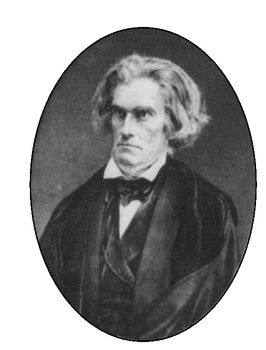

Senator John C. Calhoun, the

voice of Southern states’ rights

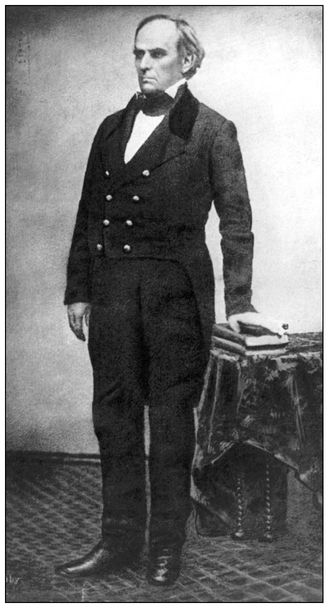

Senator Daniel Webster,

“the Godlike Daniel” or “Black Dan”

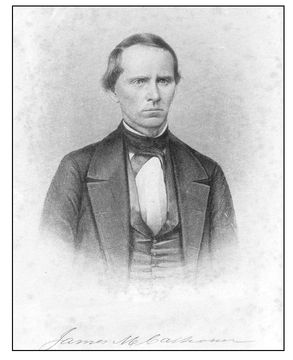

Atlanta Mayor James M. Calhoun,

cousin of John C. Calhoun

Historical artist Wilbur G. Kurtz’s bird’s eye view rendering of Atlanta in 1864 prior to the siege

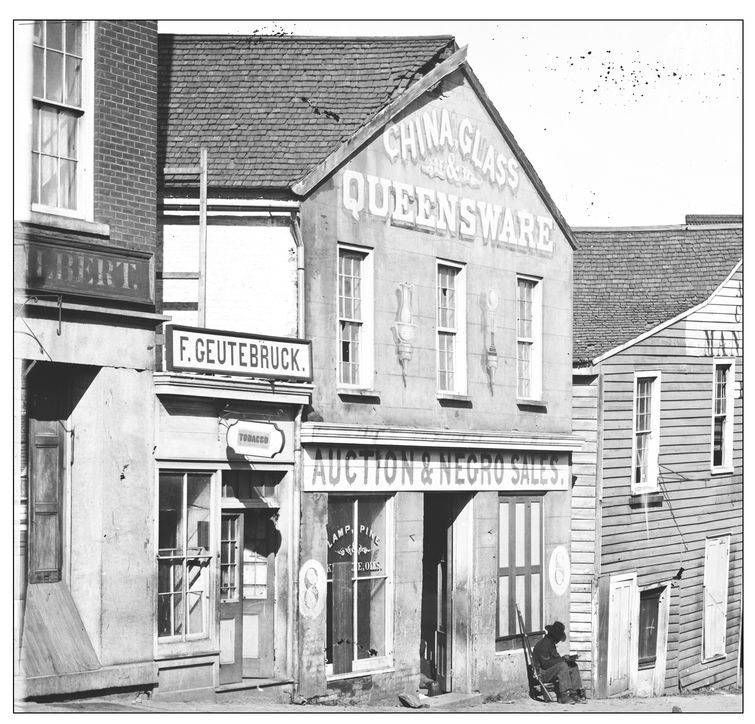

Crawford, Frazer & Co. slave market on Whitehall Street where buyers made

“their selections just as they would have a horse or mule at a stockyard”

Looking north on Washington Street: the Neal family home at the corner of Mitchell Street,where General Sherman made his headquarters, the Second Baptist Church beyond,and the Calhoun house in the distance

Train rolling into the car shed, Peachtree to Whitehall Street crossing visible

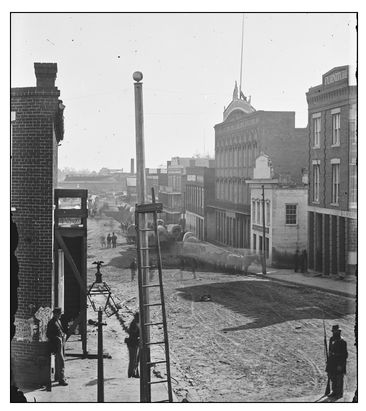

Downtown Alabama Street from the corner

of Whitehall, near the Five Points

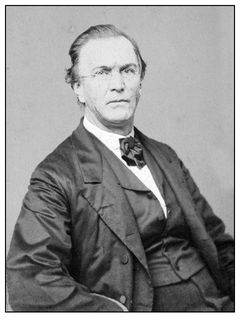

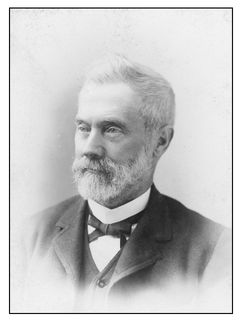

Bookseller and diarist Samuel P. Richards ran a

thriving store with his brother on Decatur Street

Plantation owner and

politician Benjamin C.Yancey

Mayor and Intelligencer owner

Jared I. Whitaker

Southern Confederacy owner

George W. Adair

Intelligencer newspaper offices on Whitehall Street,

over liquor store and next to railroad tracks

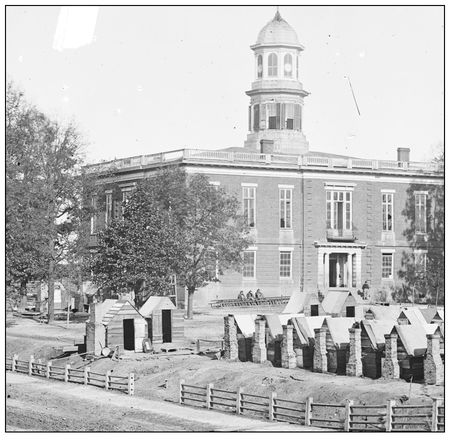

Atlanta City Hall and Fulton County Courthouse with

2nd Massachusetts Infantry camp in City Hall Square

Sarah “Sallie”

Conley

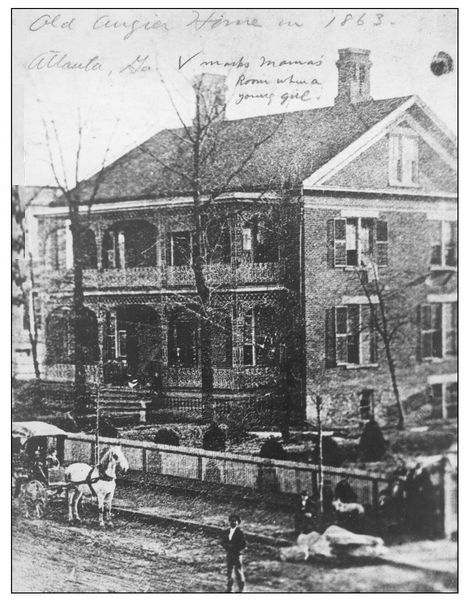

Clayton

Clayton family house on Mitchell Street

Colonel George W. Lee,

Atlanta provost marshal

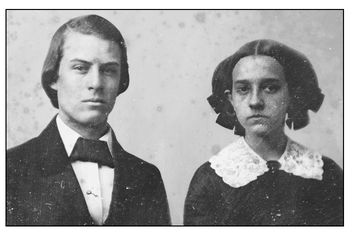

Captain and future

Mayor William Lowndes Calhoun

and wife Mary Jane Oliver