|

| OṀ. Salutations to Caṇḍikā. |

|

| Mārkaṇḍeya said: |

|

1. | OṀ. That which is the supreme secret in this world, affording every protection to humankind, which is not told to anyone—tell me that, O Grandsire. |

|

| Brahmā said: |

|

2. | There is a most hidden secret, O wise one, beneficial to all beings— the holy armor of the Devī. Hear of it, O great sage. |

|

3. | First, she is called Śailaputrī; second, Brahmacāriṇī; third, Candraghaṇṭā; fourth, Kūṣmāṇḍā. |

|

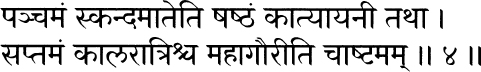

4. | Fifth, she is called Skandamatā; sixth, Kātyāyanī; seventh, Kālarātri; eighth, Mahāgaurī. |

|

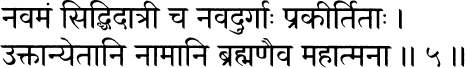

5. | And ninth, she is Siddhidātrī. The nine Durgās are revealed; the noble Brahmā has spoken their names. |

|

6. | When consumed by fire or surrounded by enemies in battle, when seized by fear in adversity or crisis, those who take refuge in the Devī |

|

7. | will have nothing inauspicious befall them amidst the danger of battle, nor will they know any misfortune that brings grief, suffering or dread. |

|

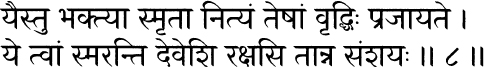

8. | Those who remember her always with devotion will surely win success. O supreme Devī, you protect those who remember you. Of that there is no doubt. |

|

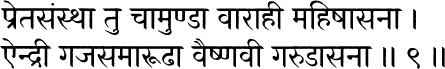

9. | Standing upon a corpse is Cāmuṇḍā; seated on a buffalo is Vārāhī; mounted on an elephant is Aindrī; seated on Garuda is Vaiṣṇavī. |

|

10. | Nārasirhhī is great in valor; Śivadūtī is great in might. Mounted on a bull is Māheśvarī, and borne on a peacock is Kaumārī. |

|

11. | Seated upon a lotus, with lotus in hand, is Lakṣmī, the goddess beloved of Viṣṇu. And the sovereign Devī who is borne on a bull, pure white is the form she possesses. |

|

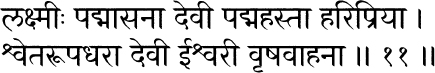

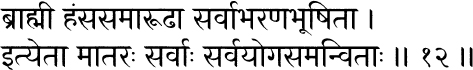

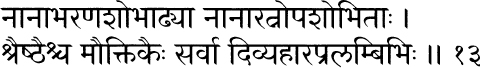

12. | Brāhmī, adorned with all her jewels, rides upon a swan. These, then, are all the Mothers, all united together, |

|

13. | arrayed in bejeweled splendor, adorned with all manner of gems: all with strands of the most excellent pearls and magic-bearing pendants, |

|

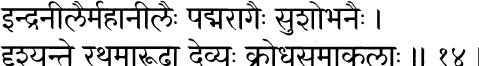

14. | with great blue sapphires and splendid rubies. Riding in chariots the goddesses appear, bristling with anger |

|

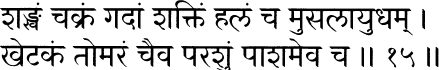

15. | and bearing conch, discus, mace, spear, plough, and club; shield, lance, and ax and noose, |

|

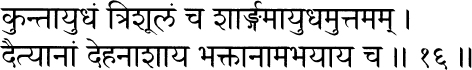

16. | pike, trident, and mighty bow—weapons to destroy the demons’ bodies and to dispel the devotees’ fears. |

|

17. | Indeed, for the well-being of the gods, they bear weapons in this manner. Salutations be unto you, great fierce one of mighty and awesome courage. |

|

18. | O you of great might and great resolve, annihilating fear, protect me, O Devī, who are difficult for our enemies to behold, for you increase their dread. |

|

19. | May Aindrī guard me in the east, and Agnidevatā in the southeast; may Vārāhī defend me in the south, and Khaḍgadhāriṇī in the southwest. |

|

20. | May Vāruṇī protect me in the west, and Mṛgavāhinī in the northwest; may Kaumārī protect me in the north, and Śūladhāriṇī in the northeast. |

|

21. | May Brahmāṇī guard me above, and Vaiṣṇavī below. In this way, may Cāmuṇḍā, riding upon a corpse, guard the ten directions. |

|

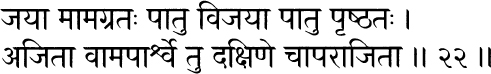

22. | May Jayā stand in front of me, and Vijaya stand behind; Ajitā on my left, and Aparājitā on my right. |

|

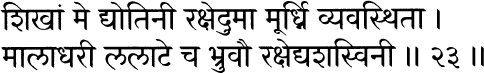

23. | May DyotinI guard my topknot. May Umā abide atop my head, and Mālādhan on my forehead. May Yasasvim guard my eyebrows. |

|

24. | May Citranetrā abide in my eyes, and Yamaghaṇṭā in my nose. May Trinetrā protect me with her trident, and Caṇḍikā dwell between my eyebrows. |

|

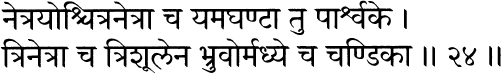

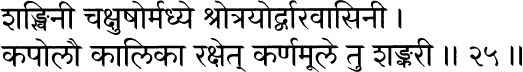

25. | May Śaṇkhinī abide between my eyes, and Dvāravāsinī upon my ears. May Kālika guard my cheeks, and Śaṇkarī protect within my ears. |

|

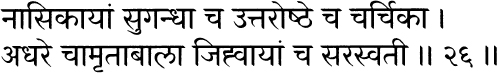

26. | And may Sugandhā protect my nostrils. May Carcikā abide on my upper lip, Amṛtābālā on my lower lip, and Sarasvatī on my tongue. |

|

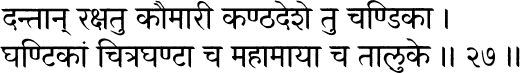

27. | May Kaumārī guard my teeth, and Caṇḍikā my throat. May Citraghaṇṭā guard my uvula, and Mahāmāyā abide in my palate. |

|

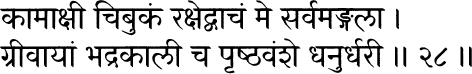

28. | May Kārnāksī guard my chin, Sarvamangalā my voice, Bhadrakālī the nape of my neck, and Dhanurdharī my spine. |

|

29. | May Nīlagrīvā abide outside my throat, and Nalakūbarī within. May Khadginī guard my shoulders, and Vajradhāriṇī my arms. |

|

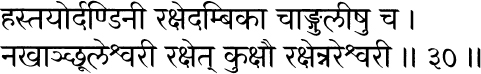

30. | May Daṇḍinī guard my hands; may Ambikā abide in my fingers. May Śūleśvarī guard my nails, and Nareśvarī my abdomen. |

|

31. | May Mahādevī guard my chest, and Śokavināśinī my mind. May the Devī Lalitā abide in my heart, and Sūladhāriṇī in my stomach. |

|

32. | May Kāminī guard my navel, Guhyesvarī my private parts, Durgandhā my penis, and Guhyavāhinī my anus. |

|

33. | May Bhagavatī guard my hips, Meghavāhanā my thighs, Mahābalā my shanks, and Mādhavanāyikā my knees. |

|

34. | May Nārasiṁhī abide in my ankles. May Kauśikī guard my heels, SrTdharī my toes, and Pātālavāsinī the soles of my feet. |

|

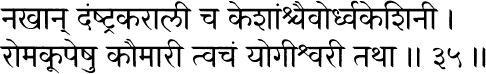

35. | May Daṁṣṭrakarālī guard my toenails, and Ūrdhvakeśinī my hair. May Kaumārī abide in my pores, and Yogīśvarī protect my skin. |

|

36. | May Pārvatī guard my blood, bone-marrow, lymph, flesh, bones, and fat. May Kālarātri guard my intestines, and Mukuṭeśvarī my bile. |

|

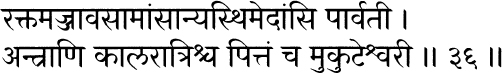

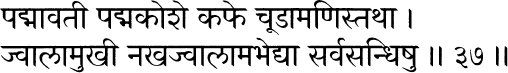

37. | May Padmāvatī guard my lungs, and Cūdāmaṇi my phlegm. May Jvālāmukhī protect the luster of my nails, and Abhedyā dwell in all my joints. |

|

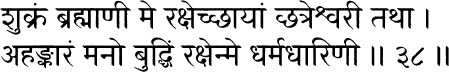

38. | May Brahmāṇī guard my semen, and Chatreśvarī my shadow. May Dharmadhāriṇī protect my ego, mind, and intellect, |

|

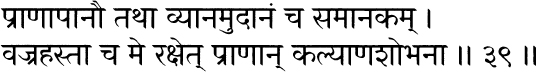

39. | and likewise my breath, elimination, digestion, nervous system, and body heat. May Vajrahastā, who sparkles with auspicious beauty, guard these, my vital forces. |

|

40. | May Yoginī abide in taste, form, smell, sound, and touch; and may Nārāyaṇī ever guard my knowledge, action, and desire. |

|

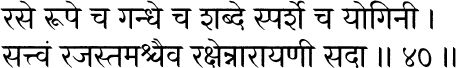

41. | May Vārāhī protect the span of my life; may Pārvatī protect my virtue; may Vaiṣṇavī protect always my honor, reputation, and prosperity. |

|

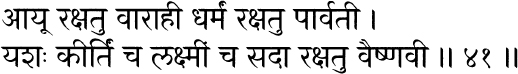

42. | May Indrāṇī guard my stable, and Caṇḍikā my herds. May Mahālakṣmī protect my children, and Bhairavī, my wife. |

|

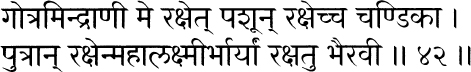

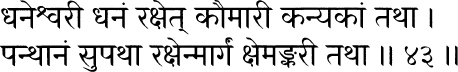

43. | May Dhaneśvarī guard my wealth, and Kaumarī, my virgin daughter. May Supathā guard my way, and Kṣemaṅkarī also. |

|

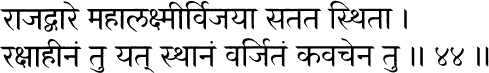

44. | May Mahālakṣmī dwell at my gate, and Vijayā be ever abiding. That which remains excluded and wanting for protection by this armor, |

|

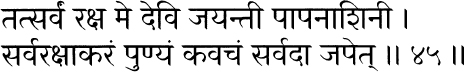

45. | all that protect, O Devī, who conquer and destroy all evil. At all times should one invoke this holy armor that affords all protection. |

|

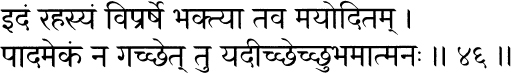

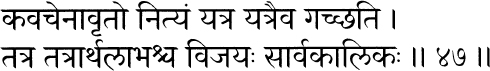

46. | This secret have I revealed, O wise one, by reason of your devotion. If one seeks his own well-being, he should not take a single step |

|

47. | unclothed by this armor, wherever he goes. Everywhere he will attain his ends, victorious, at all times. |

|

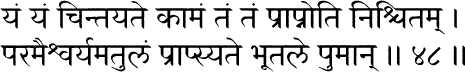

48. | Whatever desire he contemplates, that will he surely obtain. That man will attain unequaled supremacy on this earth. |

|

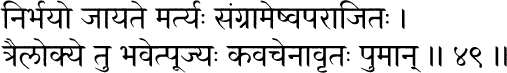

49. | That mortal will become fearless and unvanquished in battles. The man clad in this armor is to be worshiped in the three worlds. |

|

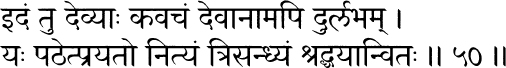

50. | This armor of the Devī is difficult for even the gods to obtain. He who recites it always at dawn, noon, and dusk, intent on devotion and possessed of faith, |

|

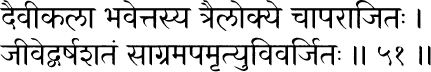

51. | attains a portion of the Divine and remains unconquered in the three worlds. He will live for a full hundred years, untouched by sudden or accidental death. |

|

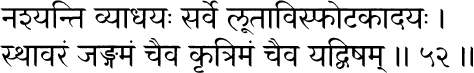

52. | All his ailments will vanish—skin infections, eruptions, and the like—along with all manner of natural poisons and those of human artifice, |

|

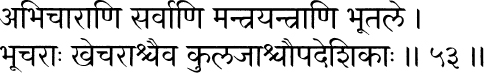

53. | all spells, incantations, and magical charms in the world. Those creatures that go upon the earth, move through the air, and dwell in water, be they induced by others, |

|

54. | self-arisen or family-born; the dākinī, the śākinī, and such: the terrible, howling dākinīs that move through the atmosphere, |

|

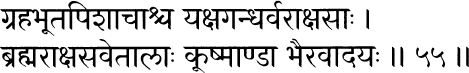

55. | the spirits that possess, fiends and apparitions, ghosts, demons, and ghouls, the undead, spirits of terror, and the like, |

|

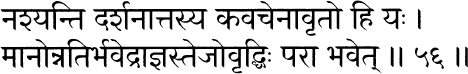

56. | all those perish at the sight of him who is clad in this armor. The king will hold him in high regard, and the spreading of his glory will know no bounds. |

|

57. | Increased renown will be his, and his fame will be exalted. For this reason, the devotee should always recite the wish-fulfilling armor, Owise one. |

|

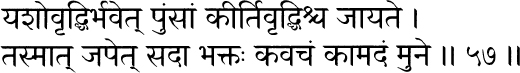

58. | Having first done this, he should recite the Caṇḍī of seven-hundred verses. Without interruption he should accomplish his recital of the Caṇḍī. |

|

59. | As long as the earth’s globe, with its mountains, forests, and groves, endures, so long will his continuity through sons and grandsons last on this earth. |

|

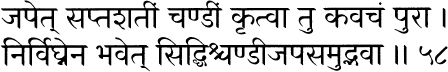

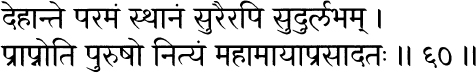

60. | At death this person, through Mahāmāyā’s grace, will attain the supreme, eternal state, greatly difficult for even the gods to reach. |

|

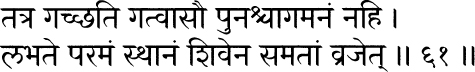

61. | He will go there, and having gone shall surely not return. He will attain the supreme state and with the Absolute will merge. |

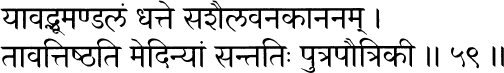

To recite the Devyāḥ Kavacam (“Armor of the Devī”), or Kavaca, is to don its protection. The verses invoke individual śaktis who together represent the full array of the Devī’s protective energies residing in the human body.

1–2: Mārkaṇḍeya, assuming the role of disciple, asks Brahmā to reveal the supreme secret. The god replies that such hidden knowledge exists in the form of the Devī’s indwelling presence.

3–5: Brahmā first reveals the names of Durgā’s nine aspects. Sailaputrl (“daughter of the mountain peak”) denotes her purificatory power as the deified Gaṇgā, flowing from the Himālayas. Brahmacāriṇī (“the one who moves in Brahman”) denotes her dynamic power, Śakti. Candraghaṇtā (“she whose bell is like the moon”) emphasizes benign creativity. Kūsmāṇdā, derived from the word for a plump gourd, represents fertility. Skandamātā is the mother of the war god, Skanda. Kātyāyanl represents the Devī’s supreme form, containing the three guṇas. Kālarātri (“black night”) indicates her power of cosmic dissolution. In total contrast, MahāgaurI (“great shining one”) signifies the dazzling light of knowledge. Finally, Siddhidātrī designates the Mother’s power to grant supreme spiritual attainment.

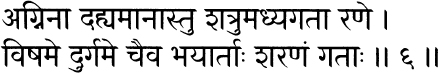

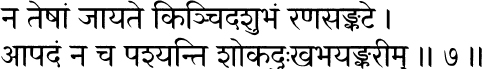

6–8: Listing some of the benefits of taking refuge in the Devī, this passage closely resembles the phalaśruti of the Devīmāhātmya’s twelfth chapter.

9–18: The Mothers enumerated here do not correspond to the seven of the Devīmāhātmya plus Śivadūtī and Cāmuṇḍā. The Kavaca names eleven.

19–22: This section invokes divine protection in the ten directions and to the reciter’s front, back, left, and right. The names of the divine energies and their meanings are: Aindrī (Indra’s śakti), Agnidevatā (“deity of fire”), Vārāhī (the śakti of Viṣṇu in his boar incarnation), Khaḍgadhāriṇī (“sword-wielder”), Vāruṇī (the śakti of Varuṇa, the Vedic god of the sea), Mṛgavāhinī (“deer-rider”), Kaumārī (the śakti of Kumāra, god of war), Śūladhāriṇī (“spear-bearer”), Brahmāṇī (the consort of Brahmā, embodying creative power), Vaiṣṇavī (the śakti of Viṣṇu), Cāmuṇḍā (Kālī as the bridger of transcendental and relative consciousness), Jayā (“victory”), Vijayā (“triumph”), Ajitā (“unconquered”), and Aparājitā (“invincible”).

23–38: The protective energies are invoked throughout the body, starting at the crown of the head and working downward. The topknot refers to the tuft of hair on the top of the head; in pūjā the bīja hrīm is linked to it as the protecting and invoking mantra. As written, the angas would have been recited by married males of the higher castes, and some verses refer specifically to the male body or to masculine societal roles. If the reciter is female, she is free to make the necessary alterations in the references to male genitalia and reproductive function in verses 32 and 38. Similarly, in verses 42 and 43, a married female would change “wife” to “husband,” and a celibate monastic of either gender would substitute “devotion” for “wife,” and “disciples” for “children.”1

The names of the powers usually have an obvious bearing on the body part or function specified. They are: Dyotinī (“brilliant”), Umā (another name of Pārvatī, linked by some philologists to ancient Semitic or Dravidian terms for “mother”), Mālādharī (“garland-wearer”), Yasasvinī (“renowned”), Citranetrā (“clear-eyed”), Yamaghantā (“holder of the bell of restraint”), Trinetrā (“three-eyed”), Caṇḍikā (“violent, impetuous”), Sankhinī (“possessor of the conch”), Dvāravāsinī (“dweller at the portal”), Kālikā (“black”), Śarikarī (“causing prosperity”), Sugandhā (“fragrant”), Carcikā (referring to the repetition of a word in reciting the Veda), Amrtabālā (“drop of nectar”), Sarasvatī (“flowing”), Kaumārī (“maidenly, virginal”), Citraghaṇṭā (“clear-sounding”), Mahāmāyā (“great deluding power”), Kāmāksī (“she whose soul is love”), Sarvamarigalā (“all-auspicious”), Bhadrakālī (“auspicious Kālī”), Dhanurdharī (“bow-bearer”), Nīlagrīvā (“blue-necked”), Nalakūbarī (perhaps a feminine counterpart of Nalakūbara, the son of Kubera), Khadginī (“possessor of the sword”), Vajradhāriṇī (“bearer of the thunderbolt”), Daṇdinī (“possessor of the staff’), Ambikā (“Mother”), Sūleśvarī (“ruler of the spear”), Naresvarī (“ruler of humankind”), Mahādevī (“Great Goddess”), Sokavināśinī (“destroyer of anguish”), Lalitā (“playful”), Śūladhāriṇī (“spear-bearer”), Kāminī (“goddess of love”), Guhyesvari (“sovereign of secrets”), Durgandhā (“ill-smelling”), Guhyavāhinī (“tortoise-rider”), Bhagavatī (“blessed”), Meghavāhanā (“cloud-rider”), Mahābalā (“she of great strength”), Mādhavanāyikā (“mistress of Viṣṇu”), Nārasiṁhī (the śakti of Viṣṇu’s incarnation as a man-lion), Kauśikī (the Devī’s sattvic aspect, who emerged from Pārvatī’s kośa, or physical sheath), SrTdharī (“bearing splendor”), Pātālavāsinī (“the dweller below”), Damstrakarālī (“she of terrifying fangs”), Ūrdhvakeśinī (“she whose hair stands on end”), Kauberī (the śakti of Kubera, the Vedic god of wealth), Yogīśvarī (“sovereign of ascetics”), Pārvatī (Siva’s divine consort in her beneficent aspect), Kālarātri (“dark night,” referring to the Devī’s world-destroying power), Mukuteśvarī (“sovereign of the crown”), Padmāvatī (a name of Lakṣmī, associated with the lotus), Cūdāmaṇi (“crest-jewel”), Jvālāmukhī (“flame-faced”), Abhedyā (“unbreakable”), Brahmāṇī (Brahmā’s consort), Chatreśvarī (“possessor of the royal parasol”), Dharmadhāriṇī (upholder of righteousness).

39: The generic term for the life force is prāṇa (“breath”), but prāṇa has five functions. More specifically, the term prāṇa denotes respiration; apāna governs elimination; samāna effects digestion, the assimilation of nutrients, and the circulation of the blood; vyāna, pervading the body, governs the nervous system, speech, and conscious action; udāna regulates growth and body heat.2 The protective śakti is Vajrahastā (“she who holds the thunderbolt in hand”). Similarly, three śaktis invoked in verses 36 and 37 afford divine protection over the three bodily humors of Ayurvedic medicine: pitta (bile, of which the chief quality is heat), vāta (wind, represented in the text by the lungs), and kapha (phlegm, of which the chief quality is cold).

40: The five senses—taste, sight, smell, hearing, and touch—are protected by Yoginī. The three guṇas—sattva, rajas, and tamas—can be taken as metaphors for knowledge (jñāna), action (kriyā), and desire (icchā), relating to the universal fact that human beings think, act, and feel. The śakti is Nārāyaṇī, the Devī as the ultimate goal of all humanity.

41: This verse deals with life span, the conduct of life, and the rewards of living in accordance with the dharma. The three guardian powers are cited previously in the Kavaca.

42–43: Invoked to watch benevolently over the reciter’s material wealth, family, and the conduct of his life are Indrāni, Caṇḍikā, Mahālakṣmī, Bhairavī (“frightful”), Dhaneśvarī (“lady of wealth”), the previously cited Kaumārī, Supathā (“she whose path is good”), and Ksemankarl (“giver of safety”).

48–61: The concluding section, in the form of a phalaśruti, details the this-worldly and spiritual benefits of reciting the Kavaca. Verses 53 through 56 present a list of supernatural entities against which the text affords protection: the dākinī (a flesh-eating female attendant of Kālī), the śākinī (a fierce attendant of Durgā), the grahabhūta (a spirit that possesses), the piśāca (the vilest of demons, according to the Ṛgveda), the yakṣa (a harmless ghost or apparition), the gandharva (usually a celestial musician, but sometimes a malevolent, disembodied spirit), the raksasa (a demon that haunts cemeteries and harasses human beings), the brahmaraksasa (the ghost of a brāhmaṇa who led an unholy life), the vetāla (a vampire or spirit inhabiting a corpse), the kūṣmāṇdā, and the bhairava (kinds of frightening demons that accompany Śiva). Ending on a positive note, the Kavaca promises that the devotee who recites it will proceed from a position of highest honor in this world to the supreme goal of union with the Divine.