2

A Methodist Life

Randal Maurice Jelks

Jackie Robinson was a Methodist. However, what exactly did that mean? Robinson’s mother Mallie was a devoted and prayerful Christian woman who shepherded her family through an arduous migration from Cairo, Georgia, to Pasadena, California. This journey of faith, for sure, was no less grueling than the one that the ancient Hebrews had undertaken when escaping through the desert from the clutches of the fabled biblical Pharaonic Egypt. Only this time the Moses of the story was a woman, Mallie Robinson, who with the aid of a half brother led her five children—Edgar, Frank, Jack, Mack, and Willie Mae—across the country, seeking more freedom from U.S. apartheid so that they could earn a living, gain an education, and live as respected citizens. Mallie’s decision was an act of faith. It was one that influenced all the Robinson children. Each would imbibe her deep sense of faith in some form or fashion, especially Jack Roosevelt Robinson, otherwise known as Jackie Robinson.

Upon her arrival in Pasadena, Mallie would find fellowship at Scott Methodist Church. The church was named after of one of the first African American bishops in the Methodist Church, Isaiah Benjamin Scott. The highly accomplished minister served as a missionary bishop in Liberia, as the first African American president of Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, and as a state commissioner at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and the Atlanta Exposition two years later.1

The Pasadena church’s name and connectivity within the Methodist Episcopal Church meant that the congregants aspired to a kind of Christian experience that was beyond the boundaries of the racial status assigned to its members in 1903. The church was founded as the legalized status of African Americans was diminished both legally and culturally to second-class citizenry. De facto and prescribed legalities conscribed life for all African Americans, including ones living in California, at the turn of the nineteenth century to the twentieth. As lovely as Pasadena’s physical geography is, racial harassment was par for the course when Scott Methodist Church was formed.2 Like other black churches, Scott was an institutional haven for African American denizens of the city.3 Although the greater world sought to punish African American communities, the collective faith practiced inside of these churches allowed its members to dream beyond everyday racism and wage struggles on behalf of their human dignity. When Mallie Robinson and her children joined Scott Church, they became a part of a community, fellowship, and network bigger than themselves. These connections helped to form the aspirations and worldview of the Robinsons and their fellow congregants.

The migration, resettlement, and construction of a new life were all expressions of Mallie’s deep faith. As Jackie Robinson biographer Arnold Rampersad rightly observes, Mallie’s faith was omnipresent: “Family was vital to Mallie, but God was supreme. For her, as she tried to make her children see, God was a living, breathing presence all about her, and she seeded her language with worshipful allusions to the divine. ‘God watches what you do,’ she would insist; ‘you must reap what you sow, so sow well!’ . . . ‘Prayer,’ she often told her children, ‘is belief.’”4 Mallie’s belief is further confirmed by Michael Long and Chris Lamb in Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography.5 However, what the authors miss in their descriptions is that Robinson’s faith development cannot be captured by a narrative focusing on one extraordinary individual’s beliefs. It is equally a story about the institutional parameters that provided the context for the development of individual convictions. Because religious faiths always have institutional contexts, it is important to set Robinson’s individual beliefs inside the context of church teachings (doctrines), clerical impact, and denominational history.

The Methodist Church began in eighteenth-century England under the auspices of John Wesley, an Anglican priest. The Anglican Church was the official church of England, and its history was part of the spread of Protestantism that began with Martin Luther’s theological disputations with the Roman Catholic Church in the city of Wittenberg, Germany. Of course, the Anglican Church’s beginnings had nothing to do with a theological disputation and everything to do with marriage and male succession to the throne. It had been formed by King Henry VIII under the Tudor dynasty. By the mid-eighteenth century, when John Wesley began to contemplate his ministry to the English urban poor and the slowly emerging proletariat, the Anglican Church was fully ensconced as the cultural arbiter of British society.

In 1738, Wesley described a Christian mystical experience: “I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins.” This spiritual transformation led Wesley to believe that personal faith could instantly transform human behavior. Faith was efficacious for him in the same way that prayer was for Mallie Robinson.

By 1739, Wesley was preaching outdoors to the emerging English working classes. Camp meetings and tent revivals would be the forerunner of today’s stadium rallies in the arsenal of rising global evangelicalism.6 Wesley also formed local groups for prayer and Bible study. His shaping of how working-class men and women thought about their collective identities was equal to that of the Chartist movement, Marxism, or socialism. Wesley helped to shape a Christian identity amid a rising new social class identity.

While still belonging to the Anglican Church, Wesley emphasized teachings that stressed personal salvation in four basic tenets: all need to be saved (the doctrine of original sin), all can be saved (universal salvation), all can know they are saved (assurance), and all can be saved completely (Christian perfection).7 These doctrines gave Wesley’s followers an assurance of salvation and the idea that God was not some distant ruler in the sky but a God who, through their relationship to Christ, cared for their existence. This faith conviction had racial implications. To be a Methodist was to be engaged in a pursuit of biblical holiness. God gave human beings the ability to make changes within themselves by pursuing Christ’s teachings, and those changes, if pursued vigorously, would lead to society becoming wholesome or, in other words, holier.

After Wesley’s death, Methodists in England would leave the Anglican Church and form their own separate entity. Methodism then spread throughout the British Empire. One of its greatest impacts would be in the British colonies in the Caribbean and through the southern portion of its colonies in North America.8 Methodists initially enshrined freedom and abolitionism as part of their tenets of holiness. However, they would soon compromise on the latter issue because of slavery’s decisive capital power in the southern colonies.

By 1794, many formerly enslaved African Americans in Philadelphia began their own Methodist movement with a mass protest at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church over their sacred rights and racial equality among members of the church.9 This protest was officially led by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, but it was also unofficially organized through a network of Methodist women.10 The protest foreshadowed the formation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church as an independent denomination. But even when enslaved African Americans were not visible institutionally, they used meeting structures within Methodism to create a system of their own faithfulness.11 In the meantime, Methodists as a whole contended with contentious internecine rivalries over the issue of slavery in 1844. This theological crisis over the most extreme exploitation of human labor as a means to wealth questioned everything that John Wesley held dear.12 And we cannot forget that the forebears of Jackie Robinson in Georgia were the brutalized laborers of this iron-fisted capitalist system of exploitation. The Methodist Church in the United States thus remained in division over the issue for ninety-five years.

This history is important for understanding Jackie Robinson. Whether he knew it or not, his faith was shaped by debates about socially embedded ideas and beliefs in Methodism. These debates became the sources of Robinson’s moral beliefs about the social conditions around him. For example, in his autobiography Robinson describes how he felt theologically alienated in adolescence. Despite having faith, his family was overwhelmed with the structural conditions of the Great Depression, which appeared to him to render faith as foolishness. He could not reconcile himself intellectually to the social exclusion factored into the most personal of daily encounters. In the eyes of an urban adolescent male, he could not reconcile his own feelings of being excluded and impoverished. The streets were more exciting and more truthful than the people in the church.

This alienation among young black men was a norm that extended back to the years of U.S. enslavement itself. It was the Achilles’ heel of black churches steeped in a piety that changing one’s heart was key to changing society. Impoverishment was itself a singular and painful alienation and reminder of social exclusivity. In addition, new forms of entertainment—arcades, bars, dance halls, motion pictures, and radio programs—provided new social outlets that challenged the pieties of mothers like Robinson’s. And this new challenge presented a crisis for black churches over questions of masculinity. Churches were highly gendered, with male clergy running the institution in a space where women and children made up the vast majority of the membership. By the time Robinson was an adolescent, the notion of being a good family meant having good churchgoing parents. Males had a godly duty to be good fathers. In Robinson’s case, his father, Jerry Robinson, had abandoned the family when Jackie was an infant, and so there was no role model of fatherly piety in Jackie’s home. In fact, Mallie’s children were all painfully aware of the absence of their father.

Churches like Scott Methodist encouraged familial piety as a way to build biblical holiness; they also created aspirational values as to how family life was to be enacted. Through church teachings, nuclear families became the bourgeois norm of what a family should look like. However, in black communities, legalized segregation, sharecropping, and the Great Depression told another story, one about families in distress.13 In Robinson’s story, running the streets appeared more visceral and engaging than attending church. What Jackie went through, however, was a growing crisis within many black denominations over its male youth.14

This brings us back to Scott Methodist Church and the issue of denominational structure. In the post-Emancipation era, black people who aligned with the Methodist Episcopal Church were partners in creating a variety of regional educational institutions, especially colleges. Wiley College was founded in 1873 in Marshall, Texas, and Samuel Huston College in Austin, Texas, opened its doors in 1900. These institutions became the training ground for an emerging leadership class within the denomination as well as in a societal struggle to make the United States an inclusive democracy.

When the Methodist bishop appointed Reverend Karl Everette Downs to Scott Church in 1938, it was of singular importance, as Jackie Robinson noted.15 Downs was from a clergy household; his father was a Methodist minister. Downs was also from the era when the black Social Gospel was being promoted by clergy and scholars such as Benjamin Mays and Joseph W. Nicholson, whose groundbreaking book, The Negro’s Church, took the temperature of black churches in the Depression. Their survey showed the activism and the self-defeating behaviors of black congregations and set the tenor for black theologians in claiming the mantle of church-based activism and spirituality—what has been dubbed the Social Gospel, a progressive movement that began with New York City pastor and theologian Walter Rauschenbusch.16

Downs brought a zeal to Scott Church, and the church’s motto under his leadership read “A Crusading Body Seeking to Establish a Divine Society.”17 The church, he believed, was there to build a just society. Additionally, he was a well-trained pastor who understood that his parishioners faced the triple burdens of exclusion by gender, race, and social class in the very minutia of their lives. Under his leadership, Scott Church became a haven where congregants could build strength and power for confronting the humiliation and crucifixion they faced on a daily basis. For Robinson, this is what made the church relevant.

Further, Robinson discovered that he could share his own personal predicaments and struggles with his thoughtful new pastor. Robinson was especially torn by his mother’s menial work and his own inability to support her financially. This, though it is not stated, deeply affected his sense of manhood as he thought about his athleticism and his desire to support his mother. Because of Downs’s pastoral counseling, as Rampersad notes, Robinson began to experience a “measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known.”18 Downs’s counsel, coupled with his ability to organize constructive youth programming, encouraged Jackie to see the church as a community servant.

The two remained friends and associates after Robinson left his childhood home. When Downs left Scott Church to become president of Sam Huston College, he successfully invited Robinson to join the school’s coaching staff. It would be Downs who would serve as liaison between Robinson and another Methodist, Branch Rickey. Sadly, Downs died at the age of thirty-five in 1948, not long after Robinson’s breakthrough summer of 1947.

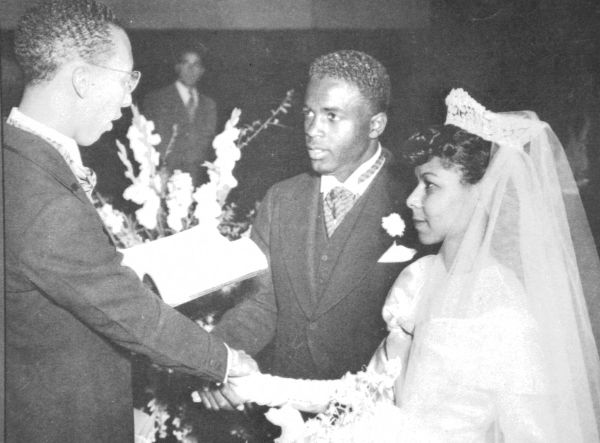

Reverend Karl Downs played a formative role in Robinson’s faith development. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

If Downs made an impression on Robinson, so did his wife-to-be, Rachel Isum. She was also a Methodist, a member of the venerable tradition of the African Methodist Episcopal Church begun under the leadership of Richard Allen.19 In fact, her home congregation—Bethel AME Church in Los Angeles—was named after Mother Bethel Church in Philadelphia, which Allen and others established after they left St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church.

The AME Church was one of the greatest institutions that African Americans created and supported during the nineteenth century. Daniel Payne, one of the church’s more illustrious bishops, helped to found Wilberforce College in Ohio, the first historically black college in the country run by African Americans.20 When Emancipation came, the AME Church spread all across the country and into the U.S. South.

From its inception, the denomination called for black folks to lift up their own from impoverished conditions. The AME Church shared general Methodist rectitude, but from its birth in 1816 it empowered black folks without the generosity of white aid. As fragile as the organization was, it believed in the strength and power of black communities long before the arrival of Black Power sloganeering. By the turn of the twentieth century, according to historian and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, the AME Church was one of the more sophisticated denominations among the Negro churches.21 The spiritual power of the church lay in its claim that black people could find biblical holiness independent of white control.

Rachel Isum’s Methodism, outside the purview of white Methodism, exuded self-determination, self-sufficiency, and black independence. These beliefs, grounded in the history of the AME Church, also served Jackie Robinson. Through Rachel, Jackie came to see that he could control his own fate and determine his own identity. This conviction was AME spirituality in a nutshell. Rachel’s influence on Robinson’s faith and religiosity was tremendous, and it remains undervalued.

When Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, began holding conversations about Robinson coming up to the major leagues, he wanted someone who could exercise discipline. Rickey used his Methodist network to discover that Robinson, a world-class athlete, could handle the scorn that would be heaped upon him as he crossed the color barrier in what was then America’s favorite pastime. Although this aspect of Robinson and Rickey’s relationship is important, we need to be careful not to be pietistic about or romanticize it. Rickey was a baseball owner; his Methodism did not affect his corporate calculations.

Robinson and Rickey might have shared denominational affiliation and spiritual affinities, but that affiliation did not trump the fact that Rickey was one of the owners of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Players in Robinson’s day were subjects of the owners; they were not free agents. That oppressive reality would not begin to change until 1969, when Curt Flood mounted a legal challenge to Major League Baseball’s “reserve clause.”22 But in Robinson’s era, owners owned their players. Rickey, as an owner, had a decisive advantage over Robinson. What Rickey needed Robinson to do was to make a profit by filling the stands. Robinson’s extraordinary prowess and his religiously undergirded middle-class norms and propriety were a match made in heaven for Rickey to publicize and market.

While it helped that both men were influenced by Methodism, this did not mean their business negotiations over pay were not difficult or contentious for Robinson. Rickey was an unwavering capitalist, and his Methodism did not supplant his desire to make more money than simply breaking even. He wished to profit off his initial investment. Robinson’s Methodism was virtually incidental; he wanted to fill the stands.

When Robinson retired from baseball, he pursued business opportunities. He also chose to align himself with the Republican Party. Black Americans still had a considerable investment in the party at that time, even though the majority of working-class black Americans had abandoned the Republican Party by 1936, voting overwhelmingly for Franklin Roosevelt. Robinson believed that the GOP was pro–small business and that it stood for lower taxes and the right of every person to be free of coercion. However, the party had long since abandoned black voters, particularly in the 1930s. It was no longer the party of Lincoln.23

We can only speculate about Methodism as a determinant of Robinson’s political views. However, it is worth highlighting the individualism of Methodism throughout history. When pursuing moral perfection, Methodists typically thought about being good individuals. They did not usually consider the corporate body or the corporate forces that shape and change the course of an individual’s life. The practice of Methodism was largely about the individual being open and willing to see the light of Christ. Though charitable to fellow human beings, Methodists often missed the point that in fact there are corporate forces and organized power working against the freedoms of individuals.

It would shake Robinson to the core that his party would follow Barry Goldwater as the 1964 Republican nominee for president. Goldwater aligned with southern Democrats in attempting to strike civil rights legislation. A fierce proponent of individual freedom, Goldwater told audiences he cast his vote in the name of liberty. This was a shock to Robinson and challenged him to dig deeper spiritually, to confront the dangerous legacy of individualism, and to serve his community and the wider culture and society.

Unfortunately for all of us, Jackie Robinson died in 1972. His diabetes left him stricken and then slowly shut down his body. He died as a man of deep faith, willing to express his deepest moral convictions with the same aggression he displayed when playing baseball. More importantly, he carried to his grave the spiritual goals that Reverend Karl Downs had encouraged him to adopt:

To be able to recognize God as the vital force in life.

To develop one’s own self to the best of one’s ability.

Not only to stay out of evil—but to try to get into good.

To seek to help others without thinking so much of what we will get out of it, but what we are putting into it.24

These were words that strangely warmed the heart, to paraphrase John Wesley. Robinson lived a strong and faithful life, just as his mother had prayed for. He kept the faith.