5

A Champion of Nonviolence?

Mark Kurlansky

Edward O. Wilson, the distinguished biologist who declares himself a pacifist, assured me that human beings are “hardwired for violence.” Not to leave me too discouraged, he pointed out that ants, his expertise, are even worse. He opined that the world would last for only minutes if ants could get nuclear weapons. He also pointed out that humans do not always have to follow their wiring. After all, they are doubtless not wired to wear clothes, eat with forks, or carry out numerous other practices that we consider civilized. They are certainly not hardwired for monogamous marriages.

And so when it is pointed out, and it often is, that nonviolence was not in Jackie Robinson’s nature, this is not a pivotal point. It was not in Mohandas Gandhi’s nature or Martin Luther King’s. Nonviolence, as Robinson was to learn on baseball diamonds, takes tremendous discipline and self-control. It is unfortunate that these men tend to be regarded as saints. As George Orwell wrote in his critique of Gandhi, “Sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid.”1 To make saints out of Gandhi and King, or even Robinson, is to miss what is most valuable about their legacies. These were pragmatic men who had concrete goals and reasoned that nonviolence was the political tool to achieve them.

My favorite Gandhi quote is this: “Whether mankind will consciously follow the law of love, I do not know. But that need not perturb us. The law will work just as the law of gravitation will work whether we accept it or no.”2 It was a pragmatic rather than a moral argument. It works.

Robinson was always in the spotlight because he was an extraordinary athlete—famous as a track and football star at UCLA and, with little experience, the man who not only integrated Major League Baseball but played it with a rare verve and excitement. And because all this happened at just the right time in history, this star athlete became a prominent civil rights figure. He was, as David Halberstam put it, “History’s Man.”3

And yet he instinctively refused to fit neatly in the roles offered him. He was a Nixon supporter, a Rockefeller Republican, a supporter of the Vietnam War, and he always refused to be considered a nonviolent activist.

The nonviolent civil rights movement began during World War II, started by a group of pacifists who went to prison for opposing the war. Some were black, such as James Farmer and Bayard Rustin, and some white, such as George Houser and David Dellinger. They formed CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, in Chicago in 1942. They had as an advisor a student of Gandhi, Krishnalal Shridharani. But there were other influences. Bayard Rustin was a Quaker raised in the moral arguments of nonviolence. Another Quaker, Richard Gregg, a lawyer, ran across the writings of Gandhi in the 1920s and, after studying them, traveled to India and studied on Gandhi’s ashram for seven months. When he returned to the United States in 1929, he became the leading spokesman of Gandhism in America. His 1934 book, The Power of Nonviolence, was read by young activists. This book also emphasized the pragmatic argument that nonviolence works.

Martin Luther King was introduced to the idea of nonviolent resistance in 1949 as a student at Crozer Theological Seminary. He attended a lecture on nonviolence by one of its leading advocates, A. J. Muste, Bayard Rustin’s mentor. King argued vehemently against Muste’s ideas, saying that the only solution to segregation was armed revolution. This was a more violent argument than Robinson ever espoused, and yet no one talks of King’s violent past the way they do Robinson’s. Of course, it was all theoretical. Neither one ever engaged in violence except, in Robinson’s case, for a few youthful fist fights. It is often reported that he was in a street gang in his boyhood in Pasadena, but this “Pepper Street Gang” of Mexicans, blacks, and Asians, though they had frequent encounters with the police, was not a very dangerous group by today’s standards. They stole fruit from stores and snatched golf balls from the local course and tried to sell them back to the owners.

Later in 1949, King attended a lecture at Howard University by the school’s president, Mordecai Johnson, on Gandhi’s ideas, and he began to change his thinking. It is interesting to note that by the time King began to embrace Gandhism, India had gained independence, and Gandhi had been martyred. This may have been King’s understanding of the process.

* * *

The important facts of Jackie Robinson’s life were all about coincidences of history and the times he happened to live in. This is what gave him the opportunities of greatness, but it is widely recognized that it was his strength of character that made these events work.

That Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers organization, decided to pursue the integration of baseball at the exact moment when Gandhi’s movement was at its height and the idea of nonviolent resistance was just taking hold in the black liberation struggle in the United States, and that Rickey would employ the techniques of nonviolence in bringing Robinson into Major League Baseball, make it nearly irresistible to claim that the Dodgers had taken on nonviolence and that Jackie Robinson was a great exponent of the tactic. But even Robinson was clear that he was not a nonviolent warrior and that all this was a coincidence.

It is not clear what Rickey’s motives were, but he never tried to connect himself with the civil rights movement. Rickey was a right-wing, Bible-thumping Republican moralist. He was the son of a lay Baptist minister. In 1942 he left his post with the St. Louis Cardinals to become general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. St. Louis was a southern town with deep racist sentiments. But Brooklyn, in the Northeast with a large black population, presented other possibilities. He often spoke on his conviction that segregation was wrong. But he was a complicated figure with a list of motives. To begin with, during World War II, much of the top talent in baseball was taken away by the war and the quality of major league play notably declined. But some of the finest players in the game were playing in the Negro Leagues. By integrating baseball, the quality of major league play could be substantially improved. Major league play was Rickey’s interest. Part of his plan for integration was to weaken the Negro Leagues and the Latin American League—Cuba, Panama, Mexico, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic—whose integrated teams had considerable standing. This was why the first thing he did with his newly integrated team was take them to Cuba and Panama—to show off the new major leagues.

There has been considerable discussion about why Rickey picked Robinson to be the first black player. He was certainly not the best, and some questioned if he was good enough, although that argument quickly disappeared. He was not an experienced player. At twenty-six, the age when most players come into their prime, he had had only one year of experience in professional baseball. Rickey looked at numerous players, and all of them had better credentials and more experience. Catcher Roy Campanella, whom Rickey signed but did not bring up first, was a much bigger name, a Negro League star.

Given the weakness of Robinson’s position, it has always been assumed that Rickey decided that Robinson was the man with the strength of character to take on the demands that would be facing him. If that is true, it is a very interesting choice. Campanella had a much milder disposition. In fact, when they were teammates on the Dodgers, there were often disagreements because Campanella thought Robinson was too difficult and Robinson thought Campanella was too mild. Jackie was always known as outspoken, “fiery”; some said he had a “chip on his shoulder,” others said he just wouldn’t stand for abuse. After he became famous for his nonviolent approach to baseball, stories started coming out about his earlier violence, but most of these are unverified. Some say that when playing for the Kansas City Monarchs the year before Rickey signed him he knocked unconscious a man in Alabama who tried to stop him from using a men’s room. This may or may not be true.

So had Rickey made the decision that it would be more effective for the public to watch the fiery Negro restraining himself than the mild-mannered one shrugging it off? There is nothing in Rickey’s statements, interviews, or papers that really answers this question.

Rickey and Robinson had in common that they both had come up in integrated sports, Rickey as the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan University and Robinson as a track and football star at UCLA. Rickey may have liked having a player who was accustomed to playing with white athletes.

By the time Rickey sat down to talk with Robinson, he had a very clear program that he called his “noble experiment.”4 The program sounded a lot like classic nonviolence. No matter what teammates, opposing players, or fans did and said, Robinson was not to react. To prepare him for this, Rickey played the role of various racists. This was how the civil rights movement would train its volunteers ten years later. Rickey told Robinson that he was “looking for a player with the guts not to fight back.”5

But there was an important difference. In the civil rights movement, actions would be taken, and when attacked, the activists were not to resist. But in Rickey’s program, Robinson was to do nothing. Although Robinson was to later say he was not cut out for King’s brand of nonviolence, it was actually what came naturally to him. It was resistance. Robinson was actually the original nonviolent warrior.

Martin Luther King once described Robinson as “a sit-inner before sit-ins and a freedom rider before Freedom Rides.”6 And this was true because Robinson was naturally defiant. But he did not have the organized discipline of a nonviolent activist and did not present himself as wishing no harm to his adversaries.

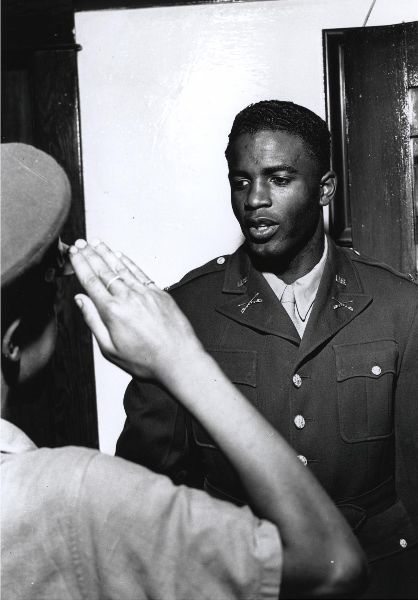

In 1942, while serving in the Army, Robinson refused to move to the back of a bus. He was court-martialed for refusing a direct order but was acquitted. The only other known freedom ride of that era was also in 1942 when Bayard Rustin, traveling alone from Louisville to Nashville, refused to move to the back of the bus. He was dragged off and, without any attempt to physically defend himself, took a severe beating while trying to explain his point of view to his assailants. It seems likely that at the time neither Rustin nor Robinson knew of the other’s resistance. But Rustin may have known of Robinson’s since he was a famous college athlete and his trial received some attention.

But the Robinson freedom ride was not the classic nonviolent tactic of Rustin or the later Rosa Parks. Lieutenant Robinson reportedly explained to a superior officer, “Captain, any Private, you or any General calls me a nigger and I’ll break them in two.”7 Insubordination to a superior officer became one of the court-martial charges.

Rickey did not want any resistance like a freedom ride. He never spoke of nonviolent activism, may have never heard of Rustin, Farmer, Muste, or Gregg. He, no doubt, had heard the Gandhi story, but there is no indication that he was inspired by it.

He may have been partly instructed by the experiences of Jewish slugger Hank Greenberg, who endured anti-Semitic taunts throughout his career in the 1930s. A giant of a man for his generation, Greenberg confronted some of his adversaries once, even following a player into the opposing locker room and challenging him to a fight. But nothing he tried ever worked until he learned to ignore the abuse. Rickey was not close to Greenberg, and there is no record of Rickey holding him up as an example. Greenberg was close to Bill Veeck, who at the same time was trying to integrate the Cleveland Indians. Greenberg was on his staff, and the Indians pursued the same tactic. Greenberg certainly understood what Robinson was doing. In 1947, Robinson’s first year as a player and Greenberg’s last, when the Dodgers were playing Pittsburgh and Robinson was silently enduring endless racist harangues, he ended up on first base. First baseman Greenberg said, “Stick in there. You’re doing fine.”8

Robinson was not an absolute pacifist. Look magazine / National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Rickey and Robinson had in common that they were both religious Christians, and so they spoke of turning the other cheek. Rickey did not discuss the writings of Gandhi or Muste or Gregg. These were activists using nonviolence as a means of attack. What Rickey wanted was true pacifism—no action whatsoever. It was in a sense political activism. Robinson’s presence was integrating Major League Baseball. But Robinson was to take no stance beyond that. And so what he handed Robinson was a book that was very popular among Christians at the time, Life of Christ, by Italian author Giovanni Papini.

This vaguely anti-Semitic book shows Jesus born into a world of crude and uncaring Jews who were not interested in his message. To be fair, according to Papini, the Romans were monsters, and even the stable where Jesus was born was filthy. Jesus lived in a miserable world.

According to Papini, the great teaching of Jesus had been “diluted by Talmudic casuistries.” The teaching is simply “Love all men near and far.”9 It is also worth noting, since Robinson was famously hot-tempered, that according to Papini, Jesus warned against anger, saying it “must be smothered at the first spark, afterward it is too late.” And then Papini relayed the most “stupefying” of Jesus’s revolutionary teachings, “Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil. But whatever might smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.”10

Papini said that there were three choices when confronted with violence: revenge, flight, and turning the other cheek. The first was barbarous, the second strengthened the enemy. Papini acknowledged that turning the other cheek is “repugnant to human nature”—E. O. Wilson’s point.11 And then he used Gandhi’s argument, that it works. It is the only way to curtail violence.

This was the book Branch Rickey gave to Jackie Robinson to read before suiting up to begin his major league career.

It can be argued whether Rickey’s approach had a tinge of racism or he was just aware of the blatant racism of the general population. He seemed to think Negroes—Robinson and his black fans as well—were children to be carefully managed. No one would have dreamed of telling Hank Greenberg, who endured vehement anti-Semitisms, or Joe DiMaggio, who faced anti-Italian attacks and was once praised in Life magazine for not smelling of garlic, how they should act. No one would have dreamed of instructing Jewish or Italian fans on proper behavior.

But Rickey seemed to think Negroes were a bit wild and tended to act up, and that the men were angry and dangerous. He would tell them how they should act. Rickey actually went to African American leaders in Brooklyn and urged them not to celebrate or cheer too much for Robinson. He told the African American community in Brooklyn not to “strut.” There were to be no parades or celebrations. “We don’t want Negroes in the stands gambling, drunk, fighting, being arrested,” he said. White racists had argued against integrating baseball because that was the way black fans would act, completely ignoring decades of successful Negro League Baseball. Rickey told black leaders it was important that the integration of baseball not be presented as “a triumph of race over race.” In other words, don’t offend the white people. Black communities organized committees to keep black fans subdued in Brooklyn and other ballparks under the slogan “Don’t spoil Jackie’s chances,” which sounds very much like Rickey-speak.12

And then there was the issue of the angry black man. This strange counter logic goes back to slavery. You could not trust a slave who was angry. Through the years, whites have been acutely aware that black people have been mistreated. Beware of the ones who were angry about it. Logic never extended to the obvious other side that the black man who wasn’t angry about it must be an idiot. Remember Barack Obama first running for president. One of the greatest hurdles was convincing white people that he wasn’t angry.

Robinson recalled his first thoughts at Rickey’s proposition. “I was twenty-six years old, and all my life back to the age of eight when a little neighbor girl called me a nigger—I had believed in payback, retaliation.”13 But Rickey convinced him, and Robinson, who never knew his real father, did not resent the older man’s patronizing attitude and said he was “the father I never had.”14

Jackie Robinson was an unmistakably angry man. He played by Rickey’s rules and kept himself under control, but you could not miss the anger. It was even in the way he played baseball—his ferocity, taunting the pitcher from the base, constantly stealing bases, even stealing home. His fierce, competitive spirit made him one of the most exciting players in the history of baseball.

Maybe this was Rickey’s plan. Maybe it was more exciting to watch a player who looked like he was about to explode always keep himself in check than a mild-mannered Roy Campanella. Larry Doby, the first black player in the American League, was a fine player for the Cleveland Indians and endured as much abuse as Robinson, but never achieved Robinson’s fame. Perhaps it was because, although he was an emotional player, fans did not sense a volatile chemistry beneath the surface.

“Hey nigger, why don’t you go back to the cotton field where you belong,” the Phillies shouted when playing at Ebbets Field. “They’re waiting for you in the jungle, black boy.”15

Robinson, who in his youth had exploded at lesser slights, who did not believe such insults should go unanswered, ignored them. It could be argued that he was embracing the nonviolent activism of the civil rights movement, but this was almost a decade earlier and Robinson made clear that what he was doing was following “Mr. Rickey’s” instructions. Mr. Rickey had listened to the public saying they would not attend integrated games because the crowd would be raucous and fights would break out on the field. He believed that if he could make sure that didn’t happen, game attendance would hugely increase, drawing the fans from the Negro Leagues and the white fans who wanted better baseball. Though he often framed it as a moral cause, it was a commercial decision. Attendance in Ebbets Field increased 400 percent in Jackie Robinson’s first season.

Robinson never denied that what he was doing was very different from what he was thinking. He was not King or Gandhi claiming that he was learning to love his adversary. King’s statement, “Do what you will and we will still love you,” was never fully embraced by Robinson.16 Robinson later confessed that he longed to drop his bat, march over to the opposing dugout from where the remarks were coming, “grab one of those white sons of bitches, and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist.”17 Of course Robinson was an athlete, a physical man. Besides, some nonviolent activists may have had similar thoughts, but it was against the rules of their program to admit it. There were quite a few loaded shotguns in nonviolent southern homes ready to defend against an attack by the KKK.

Robinson always admitted that he felt no love for these racist adversaries. He wrote later in life, “I never would have made a good soldier in Martin’s army. My reflexes are not conditioned to accept nonviolence in the face of violence-provoking attacks. My immediate instinct under the threat of physical attack to me or those I love is instant defense and total retaliation.”18

Though Robinson became a close friend and supporter of King, he never had any delusion that they were cut of the same cloth or that he, Robinson, could ever have fought in the ranks of nonviolence in the South. He wrote, “Personally I am not, and don’t know how I could ever be, nonviolent. If anyone punches me or otherwise physically assaults me, you can bet your bottom dollar that I will try to give him back as good as he sent.”19

Robinson would have never taken the beating Bayard Rustin did in his Freedom Ride, nor the beating John Lewis and many others received on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965.

The turn-the-other-cheek behavior for which Robinson became famous was pursued for only three years of Robinson’s life. He did it when Rickey took him to the minor league Royals and for two years on the Dodgers. Then Rickey concluded that he had succeeded and told Robinson he was free “to be yourself now.”20 Himself was not a raging man of violence, physically attacking adversaries, but Robinson no longer took insults and argued ferociously with anyone who he felt was denying him his dignity. He bitterly criticized Campanella for not doing more to stand up for himself.

Those three years of turning the other cheek were an extreme act of self-discipline. Robinson later wrote that it caused him periods of depression. Sportswriter Maury Allen interviewed African American pitcher Joe Black, who said of Robinson and his death from ill health at only age fifty-three, “He was a combative person by nature and that restraint went against his personality. He had to hold a lot in and it angered him terribly. Holding that much anger can really hurt a man, and I think all that name-calling in those years killed him. I really do think that.”21

Starting in 1949, Robinson was an outspoken critic of racism in baseball, spiking opposing players as he slid into bases as payback for the same having been done to him, railing against umpires for unfair treatment so rigorously that teammates had to calm him down, denouncing teams like the Yankees for being slow to integrate, and, a point that is still salient, decrying the lack of black managers. The real Jackie Robinson from 1949 until his retirement and beyond was not as popular as the perfect nonviolent hero of 1945–47, but he earned respect and, more important, felt free to be who he was. And that was exactly what Robinson intended. He wrote in his autobiography that when a white umpire told him that he had liked the old Jackie Robinson better, he answered, “I am not concerned about your liking or disliking me. All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.”22 New York Daily News sportswriter Dick Young wrote of Robinson, “He made enemies. He had a talent for it. He has the tact of a child because he has the moral purity of a child.”23

Branch Rickey had no illusions about who Robinson was. What was important was that he stuck with the program for the three years Rickey needed it. In 1963, Rickey described Robinson as “direct, aggressive, the kind that stands up when he is faced with injustice and will hit you right in the snoot.”24 This was not the Jackie Robinson of legend.

Some were disappointed and didn’t like the real Jackie Robinson. Others loved him. But many people, once they saw who he really was, were filled with admiration for the strength he showed in the performance he put on for those three years, what he could do for the cause if he had to.

On the other hand, in the 1960s, when the split came between nonviolence and Black Power, Robinson was clearly on the side of nonviolence. It was the old pragmatic argument. He believed it worked and that the opposite approach being promoted, particularly by Malcolm X, did not. He admitted that in his youth he might have been attracted to the Black Panthers if he had the opportunity. But his thinking had changed, though he was still drawn to the Panther message of self-defense.

In 1960 he wrote, “It was a lot harder to turn the other cheek and refuse to fight back then than it would have been to exercise a normal reaction. But it works because sooner or later it brings a sense of shame to those who attack you. And that sense of shame is often the beginning of progress.”25 So he had learned the strategy of nonviolent activism. It works.

Robinson spent the rest of his life as an activist for black rights whether as an executive for Chock full o’Nuts, an important African American employer, a board member and leading spokesman and fundraiser for the NAACP, an active supporter of King’s organization, or a fundraiser for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He established an African American bank, the Freedom National Bank, and supported other African American–owned companies. He had a weekly radio broadcast on race issues, and he was a celebrity marcher at many protests. He became a civil rights leader.

He was a tireless champion, and he always leaned toward King and the nonviolent movement even though, as he wrote once in his column, he did not see “how I could ever be nonviolent.”26 Though he sometimes agreed with Malcolm X, particularly on the lack of progress toward equality, he saw in the Black Power movement an encouragement of violence and hatred that he did not think was helpful. After all, Robinson was a walking symbol of integration, it was what he believed in, and the idea that blacks should be separate from whites was not appealing to him. He accused Malcolm X of hating white people, and while Robinson could not love his racist adversaries like a true nonviolence advocate was supposed to, he did not hate white people, had always lived around them, and was comfortable with them.

This is not to say that he was willing to feign friendship with those he perceived as enemies. When Barry Goldwater suggested they sit down together so Robinson could explain civil rights to him, Robinson quoted Louis Armstrong who was once asked to explain jazz. “If you have to ask,” Armstrong answered, “you wouldn’t understand.”27

Nor was Robinson an advocate for the broader strategy of nonviolence. He did not reject war and in fact supported the Vietnam War and criticized King for opposing it.

But Robinson did truly abhor violence and denounced the assassination of Malcolm X as “black hands being raised against brothers.”28 He always saw violence as disastrous for the black cause. And though he was extremely militant and often criticized other black leaders such as Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young for being too soft, he never veered from the conviction that nonviolence was the only pathway to success.

He wrote, “We are adamant: we intend to use every means at our disposal to smash segregation and discrimination wherever it appears.”29 And this sounds much like the famous declaration of Malcolm X that rights would be gotten “by any means necessary.” It was in fact very different because Malcolm X was saying that he would not rule out violence, and Robinson made clear that he did rule it out as an acceptable tactic.

In 1962 he wrote a letter to President John Kennedy in which he stated, “We do not believe in violence as a solution to the problems of the negro in this country.” But he also added a warning: “But with all due respect to the preachments of Dr. Martin Luther King, we do not believe that the Negro is going to continue to turn the other cheek when his children are denied schooling, his family denied bread and butter, when he is denied the right to vote, to strike for advancement, to live where his desire urges him and his pocket book entitles him.”30 In other words, Robinson was not willing to turn violent, but he did warn that others might turn to violence without progress.

We need not portray Robinson as a champion of nonviolence. As Orwell said of Gandhi, he should not fall into the trap of being made a saint. Jesse Jackson’s comparison of Robinson to Jesus does not seem appropriate. Like all of us, he was a flawed human being. He had a bad temper and enough bitterness to title his autobiography I Never Had It Made. He was not a violent man but could not fully embrace nonviolence. But he was a man who spent his life trying to advance his people and to use the fame he earned from phenomenal natural athletic ability to further a cause to which he was relentlessly committed.