6

The White Media Missed It

Chris Lamb

Hector Racine, president of the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ AAA team, told a packed conference room on October 23, 1945, that the team had signed Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. Camera bulbs flashed and reporters moved quickly to the front of the room, where Racine and Robinson were sitting, while others rushed to call their newspapers and radio stations.1

Racine told the reporters that his team had signed Robinson because he was “a good ballplayer,” and because it was a “point of fairness.” Blacks, Racine said, had earned their right to play in the national pastime by fighting—and in some cases dying—for their country during World War II. Robinson’s roster spot was not guaranteed. He would have to earn his Montreal uniform during spring training in Florida, Racine said. When reporters asked Robinson for a comment, he described himself as a “guinea pig in baseball’s racial experiment.”2

The announcement ended the color line in what was called “organized professional baseball” and forever changed baseball, sports, and American society.

To the black press and its readers, the announcement signaled the beginning of what they hoped would be a new day for fairness and equality. White sportswriters wondered what all the fuss was about. Black sportswriters, who condemned bigotry and, in many cases, fought for the integration of baseball, gave the story context so their readers could appreciate its significance and connect it to the larger issue of racial discrimination in society. White sportswriters kept their distance and said little beyond what Racine and Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey told them.

The newspaper coverage of Robinson’s signing helped shape his legacy in the media in the more than seven decades that have followed.

To black America, Robinson changed what it was like to be a black American. He was a hero who was willing to sacrifice his life for the cause of racial equality and equal justice. Robinson was a larger-than-life civil rights leader, a “sit-inner before the sit-ins and a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides,” as Martin Luther King Jr. described him.

To white America, Robinson was a black baseball player.

Sid Feder of the Associated Press reported within hours of the announcement that Robinson had been a star athlete at UCLA and that his signing had come after a three-year, $25,000 search by Rickey. Feder incorrectly reported that Robinson was the first black player in what was called “organized baseball.” In fact, dozens had played in organized baseball at the end of the nineteenth century, including a few in the major leagues, until team owners agreed to prohibit black players.3

In a story the next day, AP reporter Jack Hand asked Rickey, who had not been at the press conference, if his decision to sign Robinson had been influenced by politics. Rickey was emphatic in his denial. “No pressure groups had anything to do with it,” Rickey said. “In fact, I signed him in spite of such groups rather than because of them.”4

This statement was repeated in stories throughout the country. But it was not true.

Rickey co-opted the integration story, ignoring the contributions of black and communist sportswriters and progressive politicians who had demanded and agitated for the integration of baseball for more than a decade. White sportswriters and columnists accepted what Rickey told them and passed this version on to their readers, leaving them to believe that it had been Rickey—and only Rickey—who ended segregated baseball.5

Robinson’s breaking of Major League Baseball’s color barrier is the most significant sports story in America in terms of its consequences for society. Jules Tygiel, author of the extraordinary Baseball’s Great Experiment, wrote that the integration of baseball depended on the courage of Robinson and Rickey.6

Tygiel was absolutely correct. But the campaign by black and communist sportswriters to integrate baseball had little or nothing to do with either Robinson or Rickey. This part of the story went unreported in the mainstream press.

White sportswriters, particularly in New York, knew that political progressives had clamored for the integration of baseball because the city was the epicenter of the movement, but those journalists said nothing about this when Montreal announced it had signed Robinson. Sportswriters relied for the details of the story on Rickey, who said that he had signed Robinson because it was, as Racine had put it, “a point of fairness,” and because it was a matter of faith. “I cannot face my God much longer knowing that His black creatures are held separate and distinct in the game that has given me all I can call my own,” Rickey told reporters.7

The sixty-three-year-old Rickey had been involved in baseball most of his life and had rarely—at least publicly—expressed interest in ending segregation in baseball until he signed Robinson. If Rickey was taking orders from God, why did it take him so long to answer the Almighty’s call? In addition, Rickey was well aware that others had been persistently removing the color barrier brick by brick.

Baseball could not have maintained the color line as long as it did without the aid and comfort of white mainstream sportswriters, who participated in what sportswriter Joe Bostic of Harlem’s People’s Voice called a “conspiracy of silence” with team owners to keep baseball segregated. The Baseball Writers’ Association of America, like team owners, had a color line. It excluded blacks from membership. Without a press card, black sportswriters were prohibited from press boxes, dugouts, baseball fields, and dressing rooms.8

Baseball writers were far more comfortable dressing up in blackface and speaking in black dialect during their skits at their annual banquet than in writing about racism. They used racial pejoratives and stereotypes in print and in conversation. Shirley Povich, who was one of the relatively few mainstream sportswriters who advocated for blacks in baseball, was asked why so few white sportswriters called for the end of the color line. “I’m afraid the sportswriters were like the club owners,” he said. “They thought separate was better.”9

White sportswriters made no attempt to put the Robinson story in historical or sociological context. Sportswriters rarely interviewed Robinson. They relied for their quotes about Robinson on Rickey or one of his associates or one of the black or communist sportswriters who interviewed Robinson. In some cases, they simply made up their quotes. To white sportswriters, it was as if the issue wasn’t that Robinson had a different skin color; it was as if he spoke a different language.

Whatever the case, white sportswriters missed the most significant sports story in the history of baseball, and so did their readers.

* * *

On February 5, 1933, the New York Baseball Writers’ Association met for their annual dinner, where they heard speeches and testimonials about the great game of baseball and took turns cracking themselves up with songs and skits. The high point of the evening, as it was every year, was a minstrel show, where sportswriters in blackface delighted the crowd of hundreds of white league executives, players, politicians, judges, and business leaders.10

Heywood Broun, the progressive columnist of the World-Telegram, took the occasion to respond to a recent editorial in the Daily News that called for the end of the color line in baseball. In his speech, Broun said he saw “no reason” why blacks should be kept out of the major leagues and then spoke at some length about why teams should sign black players. “If baseball is really the national game let the club owners go out and prove it,” he said.11

Perhaps every sportswriter and columnist in New York City heard Broun’s speech. Only Jimmy Powers of the Daily News, who praised Broun’s suggestion, mentioned it in print. The Sporting News, the so-called “Bible of Baseball,” also ignored Broun’s appeal. The Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender, which had the highest circulation of any black newspapers in America, praised Broun and Powers and called for team owners to sign black players.12

Black newspapers recognized this critical juncture in the crusade for racial equality in baseball, and in the United States, and shared that story with their readers. Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, and other sportswriters took up the issue in their columns, where they praised Negro League ballplayers, chronicled the hopes and frustrations of their readers, and challenged the claims of the baseball establishment. Black sportswriters wrote Major League Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and league presidents and knocked on the doors of team owners, asking them to give tryouts to black players who they said would improve their teams.13

In early 1939, Wendell Smith asked National League president Ford Frick why there were no blacks in baseball. Frick said the fault for the color line rested with the racial attitudes of ballplayers and fans and not with owners and other baseball executives, who, he said, were willing to sign black players. He told Smith baseball couldn’t sign blacks until players supported it.

Smith decided to interview ballplayers to see if this was true. Smith, as a black man, could not get a press card, which would have allowed him access to dugouts and dressing rooms. Over the next several weeks Smith interviewed dozens of ballplayers and managers in the hotel where visiting teams stayed when they came to Pittsburgh to play the Pirates. Nearly all of those interviewed, including Dizzy Dean, Gabby Hartnett, Carl Hubbell, Ernie Lombardi, Mel Ott, and Leo Durocher, said they had no objections to blacks in the major leagues, and many said adding black players to their rosters would improve their teams. Smith included the responses in a series of articles.14

The Courier and other black newspapers had little readership and/or political influence outside black America. This wasn’t the case with the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the United States Communist Party in New York City, which communists used to convince like-minded people to join their cause. Unlike black journalists, the communists had political influence among social progressives in the New York State Legislature and on the New York City Council.15

Communism increased in the 1930s as a result of the Great Depression, which many Americans, particularly those on the political left, viewed as a failure of capitalism. Communists tried to recruit black Americans, who were oppressed by the white establishment and were therefore open to a political system that included them. If the communists could integrate baseball, they believed they could win over the hearts and minds of black Americans.16

The Daily Worker began its campaign to end segregation in baseball on August 13, 1936, in response to Jesse Owens’s bravura performance at the Berlin Olympics, where the black sprinter won four gold medals to counter German chancellor Adolf Hitler’s theory of a master race. In the coming decade, Worker sportswriters wrote hundreds of columns and articles on the issue of segregated baseball. They collected hundreds of thousands of names on petitions demanding the integration of baseball and sent them to Commissioner Landis. Communists challenged owners to sign black players, criticized mainstream sportswriters for their silence, and shamed the baseball establishment into defending itself against racism. Baseball executives and mainstream sportswriters called the communists “agitators” and “social-minded drum beaters,” which, of course, was true.17

In 1942, Pittsburgh Pirates owner William Benswanger told the Worker his team would give a tryout to Negro Leaguers. Even though Benswanger reneged on the promise, the announcement gave much-needed publicity to the campaign to integrate baseball. J. G. Taylor Spink, editor of the Sporting News, wrote an editorial with the headline “No Good from Raising Race Issue.” He argued that black players did not want to play in the major leagues and that mixing blacks and whites on the field would result in race riots in the stands.18 Neither of these arguments was factual.

Activists increased their pressure to integrate baseball during World War II, when the quality of play in the major leagues deteriorated as ballplayers left to join the armed service. Progressive politicians, including U.S. congressman Vito Marcantonio of Brooklyn, New York, state legislators, and New York City Council members, were among those calling for major league teams to sign black players.19

In early 1945, the New York Legislature approved the Quinn-Ives Act, making it the first state to ban racial discrimination in the workplace. Rickey, who had begun secretly scouting the Negro Leagues for players to sign, was at spring training when he read that Governor Tom Dewey was expected to sign the bill into law.

“They can’t stop me now,” he told his wife.20

Joe Bostic brought two aging Negro Leaguers to Brooklyn’s wartime spring training in Bear Mountain, New York, and demanded that Rickey give them tryouts. Rickey reluctantly agreed. After giving the players a full tryout, he said the players were too old to sign to a contract. A few days earlier, a Boston politician pressured the Red Sox to give tryouts to three talented young Negro League players: Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams. The Red Sox had high school pitchers throw batting practice, and team officials reportedly sat in the stands yelling “get those niggers off the field.”21

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, facing pressure from the political left, created a committee to end Jim Crow in baseball. Rickey, who was a member of the committee, secretly signed Robinson and hoped to sign other blacks. La Guardia told Rickey he was going to announce on radio on October 18, 1945, that the committee was making progress on integrating baseball. Rickey asked the mayor to postpone his announcement. He did not want anyone to think he signed Robinson because of politics.22

When Montreal announced it had signed Robinson, black newspapers responded as if it was the moon landing. The Chicago Defender wrote that the signing of Robinson was more than just an opportunity for the ballplayer, it was an opportunity for all blacks. If baseball could be integrated, so too could schools, theaters, businesses, and swimming pools. The New York Amsterdam News called the news “a drop of water in the drought that keeps faith alive in American institutions.” New York Age editor Ludlow Werner wrote that a lot of Americans hoped Robinson would fail. “The white race will judge the Negro race by everything he does,” Werner said. “And Lord help him with his fellow Negroes if he should fail them.”23

The Pittsburgh Courier filled its newspaper with photographs and articles, including two on the front page—one by Wendell Smith and the other with Robinson’s byline, though it was ghostwritten by Smith. The Baltimore Afro-American included a long interview with Robinson on page 1 that quoted the ballplayer as saying, “I feel that all the little colored kids playing sandlot baseball have their professional futures wrapped up somehow in me.”24

Mainstream newspapers responded with big headlines but said little of substance beneath them. There were few columns or editorials about what the signing of Robinson meant to black America or to America for that matter. Little was said about racial discrimination in America or about the reasons for the color line or about those who had fought for integration.

Few sportswriters openly opposed the signing of Robinson on the basis of his skin color, or they would have risked violating the principles of equality and opportunity that Americans proclaimed separated themselves from Nazi Germany, which America and its allies had just defeated in World War II. By saying nothing or as little as possible about Robinson’s race, historian William Simons said, “one could thus impede integration without appearing to challenge the liberal consensus.”25

Sportswriters found ways to express their objections without leaving behind their fingerprints. For instance, the Associated Press sought reactions from southern ballplayers—and not northern players—who were more likely to criticize the signing. By doing so, northern newspapers could identify racial discrimination with the South and deny that racism existed in their own region of the country.26

The Sporting News published several articles on the signing of Robinson, including its main story that included this revealing description of Robinson: “Robinson is definitely dark. His color is the hue of ebony. By no means can he ever be called a brown bomber or a chocolate soldier.” The Sporting News also included reactions from a number of the nation’s sportswriters, who responded with banal platitudes but failed to capture the story’s significance.

In an editorial, J. G. Taylor Spink downplayed the story’s importance and doubted whether Robinson was good enough to play in the major leagues. If Robinson were white and six years younger, he might be good enough for Brooklyn’s AA team, Spink said. He did not say whether he had ever seen Robinson play or talked to anyone who had.27

In his Sporting News column, Dan Daniel, the president of the Baseball Writers’ Association, agreed with his editor that the story “had received more attention than it was worth.” New York World-Telegram columnist Joe Williams wrote that Robinson must ignore “pressure groups, social frauds, and political demagogues,” who would try to exploit him to advance their personal objectives. A number of sportswriters and baseball officials said they didn’t object to Robinson in baseball as long as he was the “right type” of black and that he was “a credit to his race.” Robinson, they said, would get a fair chance in baseball as long as he was a “good black,” like Jesse Owens, and not a “bad” one, like former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson.28

Most baseball executives said they had no comment. But when Philadelphia sportswriters asked Connie Mack about Robinson, he said he no longer had respect for Rickey and the Athletics would not take the field if the Dodgers brought Robinson to his team’s spring training site in West Palm Beach, Florida. The sportswriters who heard Mack’s racist tirade agreed not to publish it.

“I decided I’d forgive old Connie for his ignorance,” Red Smith later said.29

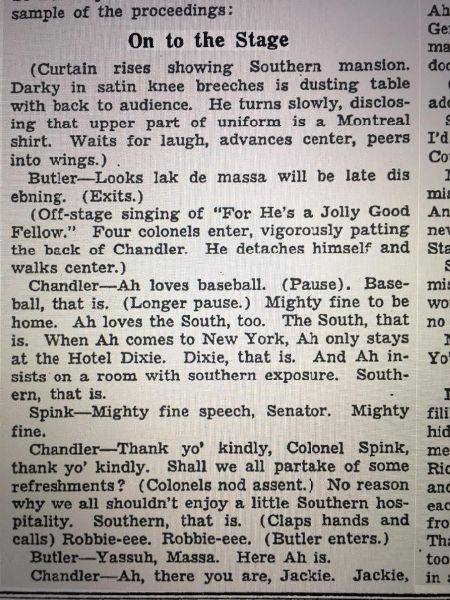

Shortly before the players, managers, coaches, and sportswriters left for Florida for spring training in February 1946, the New York Baseball Writers’ Association had their annual banquet. Arthur Daley, the revered sports columnist of the New York Times, wrote that the sportswriters spoofed the sensitive subject of Jackie Robinson but did so in such a way that “no one’s feelings really were hurt.”

To make his point, he published the dialogue of the skit: A writer dressed as Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler summoned a butler in blackface who appeared in a Montreal uniform and responded, “Yassah, Massa. Here ah is.”

“Ah! There you are, Jackie,” the Chandler character responded. “Jackie, you old wooly-headed rascal, how long you been in the family?”

“Long time, Kun’l,” the Robinson character said. “Evver since Mistah Rickey done bo’t me.”30

A description of the 1946 skit in which a blackfaced white sportswriter depicted Robinson as a butler to the baseball commissioner. New York Times.

When Wendell Smith learned of the skit, he excoriated sportswriters for their bigotry. Rickey, too, who was recovering in the hospital from a bout with Meniere’s disease, was privately incensed.31

Rickey, to his credit, did everything he could to give Robinson the best chance of succeeding in Florida. He signed a second black prospect, Johnny Wright, and hired Wendell Smith to serve as Robinson’s chauffeur, bodyguard, and father confessor. He also went to Daytona Beach before spring training to work out accommodations for Robinson and Wright, who would not be allowed to stay in the same hotel with the rest of the organization.32

There wasn’t enough room for all the players in the organization to train in Daytona Beach. The Montreal team began spring training forty miles away in rural Sanford.

Robinson spoke to sportswriters after his first day of practice on March 4. The next day’s stories included biographical information about Robinson such as his athletic success at UCLA, his military background, his statistics in the Negro Leagues, and his recent marriage to Rachel. Sportswriters praised him for his poise, intelligence, athletic ability, and sense of humor. When Robinson told reporters he weighed about 195 but wanted to get down to the 180 pounds he weighed when he played for UCLA, a reporter remarked that the extra weight didn’t show. “It’s in my feet,” he said.33

Robinson later criticized sportswriters for being combative during spring training. “They frequently stirred up trouble by baiting me or jumping into any situation I was involved in without completely checking the facts,” he said.34

In fact, sportswriters rarely, if ever, treated Robinson with outright hostility. Rather, they ignored him. White sportswriters treated Robinson as if he were a curiosity or a novelty—like a one-armed player or a thirty-five-year-old rookie.

After the second day of practice, a Klansman told Smith there would be trouble if Robinson was not out of town by sundown. Smith, Robinson, and Wright left immediately, and the Montreal team went to Daytona Beach the next day.35

Robinson struggled at the plate and injured his throwing arm trying to impress the coaches. He couldn’t hit and he couldn’t throw. Rickey moved him to first base, where he didn’t have to throw, and encouraged him to use his speed. Robinson began bunting his way on base and then stole second and third. His armed healed.36

The bigotry at Sanford surfaced in other cities. The city of Jacksonville locked the gates to its ballpark rather than allow Robinson to take the field in its segregated ballpark. Deland canceled a day game because the lights weren’t working. He was escorted off the field by a police officer in another town. Only Daytona Beach let him play that spring.37

Robinson made the Montreal roster and became its most valuable player as the team won the International League championship. Rickey signed Robinson the following spring, and he played his first game for Brooklyn on April 15, 1947.

The story had become too big for the mainstream press to ignore.

Robinson and the integration of baseball became, according to William Simons, the most talked-about story involving race relations in the years immediately following World War II.38

But you wouldn’t know that by reading the country’s mainstream newspapers. White sportswriters kept Robinson at a distance—as did Brooklyn players.

Sportswriters perpetuated the fiction that Robinson and his teammates had become good friends, reporting that Dixie Walker, a hardcore segregationist, had taken Robinson under his wing and was giving him batting tips. One columnist referred to Walker as “Robinson’s best friend and chief advisor.” Jackie’s wife, Rachel, clipped the article and wrote the following: “Some sportswriters fall for anything.” Robinson later said he had no relationship—let alone a friendship—with Walker.39

White sportswriters failed to tell the story of the integration of baseball because they made little attempt to get close to it. According to Red Smith’s biographer, the sportswriter was opposed to racial discrimination but did not feel comfortable challenging the issue in print. When Smith was later asked how he felt about the story of Robinson and the integration of baseball, he answered, “I don’t remember feeling any way except for having a lively interest in a good story.”40

If he indeed had such an interest in the story, why did he not write anything about it?

The same could be asked of most of the white sportswriters who failed to tell the story of Robinson and the integration of baseball and, in doing so, denied their readers the opportunity to understand what the story meant not just to baseball but to society. They thus denied their readers the context necessary to make sense of a changing America.

Too many white sportswriters simply believed that the signing of Robinson meant that baseball was now integrated and that it had solved what J. G. Taylor Spink had called baseball’s “race issue.”41 That conclusion was incalculably wrong because it denied the long history of racism in baseball. These same sportswriters failed to help their readers appreciate that what Robinson did on April 15, 1947—and during his rookie season and subsequent baseball career—transcended baseball.

Jonathan Eig writes in Opening Day that Robinson, by demonstrating grace under unceasing pressure, provided an example for others who would confront racial inequality. “He proved that black Americans had been held back not by their inferiority but by systematic discrimination,” Eig writes. “And he proved it not with printed words or arguments declaimed before a judge. He proved it with deeds. That was Jackie Robinson’s true legacy.”42

More than seventy years after Robinson integrated baseball, his stature as a baseball player remains secure. But he has not yet been fully recognized for his contributions to civil rights. If white America still doesn’t appreciate Robinson’s legacy in the civil rights movement, it’s because white journalists, commentators, and historians have failed to put him in the context of the civil rights movement. If white America is ever to give Robinson the credit he deserves, the nation’s sportswriters and the rest of us must quit seeing him as just a ballplayer who broke baseball’s color barrier and recognize him as a civil rights icon who played baseball.