Like just about everything in Earth Science, this strange feature is related to plate tectonics. It’s really just a hot geyser like the ones found at Yellowstone National Park, except this geyser is found under 10,000 feet of seawater. These features, called hydrothermal vents, are found where lava eruptions hit seawater in regions where new ocean crust is being created. The hot water coming from the vent explodes from the release of pressure. Once in the cold seawater, sulfide minerals precipitate out, creating the “smoke” in the photo. As the sulfide minerals fall, they create the chimney-like structure in the photo.

Many hydrothermal vents are home to unusual life forms.

Before you can learn about plate tectonics, you need to know something about the layers that are found inside Earth. These layers are divided by composition into core, mantle, and crust or by mechanical properties into lithosphere and asthenosphere. Scientists use information from earthquakes and computer modeling to learn about Earth’s interior.

How do scientists know what is inside the Earth? We don't have direct evidence! Rocks yield some clues, but they only reveal information about the outer crust. In rare, a mineral, such as a diamond, comes to the surface from deeper down in the crust or the mantle. To learn about Earth's interior, scientists use energy to “see” the different layers of the Earth, just like doctors can use an MRI, CT scan, or x-ray to see inside our bodies.

One ingenious way scientists learn about Earth’s interior is by looking at how energy travels from the point of an earthquake. These are seismic waves ( Figure below ). Seismic waves travel outward in all directions from where the ground breaks at an earthquake. These waves are picked up by seismographs around the world. Two types of seismic waves are most useful for learning about Earth’s interior.

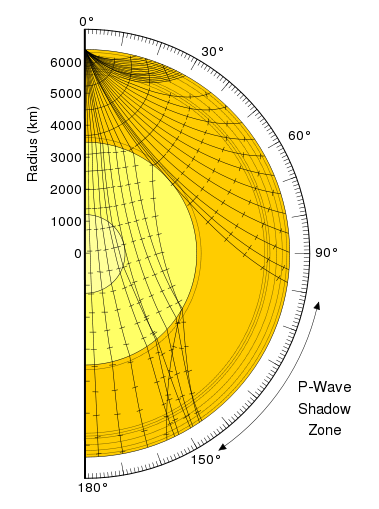

Figure 6.1

How P-waves travel through Earth

By tracking seismic waves, scientists have learned what makes up the planet’s interior ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.2

Letters describe the path of an individual P-wave or S-wave. Waves traveling through the core take on the letter K.

This animation shows a seismic wave shadow zone: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/animations/animation.php?flash_title=Shadow+Zone&flash_file=shadowzone&flash_width=220&flash_height=320 .

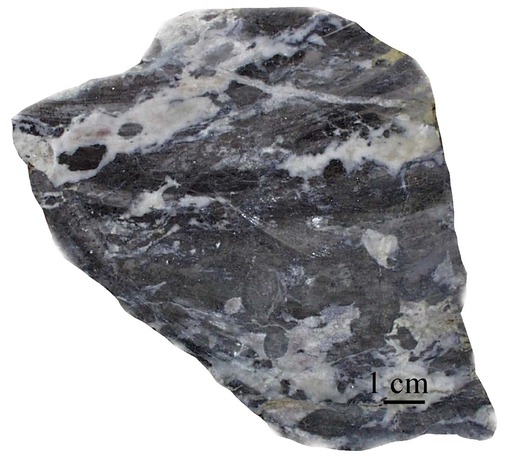

Figure 6.3

This meteorite contains the mafic minerals olivine and pyroxene. It also contains metal flakes, similar to the material that separated into Earth

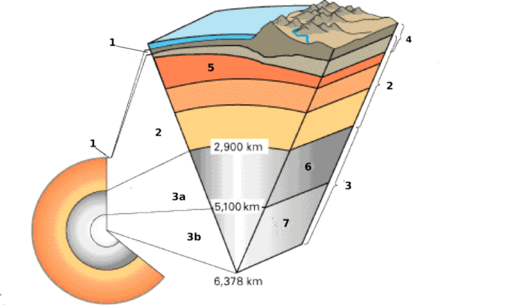

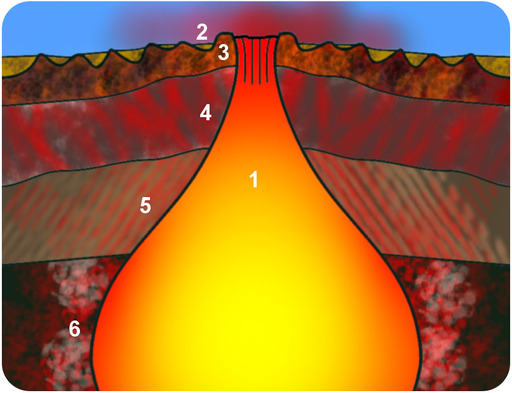

The layers scientists recognize are pictured below ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.4

A cross section of Earth showing the following layers: (1) crust (2) mantle (3a) outer core (3b) inner core (4) lithosphere (5) asthenosphere (6) outer core (7) inner core.

Core, mantle, and crust are divisions based on composition:

Lithosphere and asthenosphere are divisions based on mechanical properties:

This animation shows the layers by composition and by mechanical properties: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_layers.html .

Earth’s outer surface is its crust; a cold, thin, brittle outer shell made of rock. The crust is very thin, relative to the radius of the planet. There are two very different types of crust, each with its own distinctive physical and chemical properties, which are summarized in Table below .

Table 6.1

| Crust | Thickness | Density | Composition | Rock types |

| Oceanic | 5-12 km (3-8 mi) | 3.0 g/cm 3 | Mafic | Basalt and gabbro |

| Continental | Avg. 35 km (22 mi) | 2.7 g/cm 3 | Felsic | All types |

Oceanic crust is composed of mafic magma that erupts on the seafloor to create basalt lava flows or cools deeper down to create the intrusive igneous rock gabbro ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.5

Gabbro from ocean crust. The gabbro is deformed because of intense faulting at the eruption site.

Sediments, primarily muds and the shells of tiny sea creatures, coat the seafloor. Sediment is thickest near the shore where it comes off the continents in rivers and on wind currents.

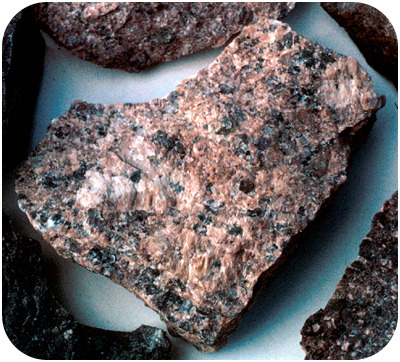

Continental crust is made up of many different types of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks. The average composition is granite, which is much less dense than the mafic rocks of the oceanic crust ( Figure below ). Because it is thick and has relatively low density, continental crust rises higher on the mantle than oceanic crust, which sinks into the mantle to form basins. When filled with water, these basins form the planet’s oceans.

Figure 6.6

This granite from Missouri is more than 1 billion years old.

The lithosphere is the outermost mechanical layer, which behaves as a brittle, rigid solid. The lithosphere is about 100 kilometers thick. Look at Figure above . Can you find where the crust and the lithosphere are located? How are they different from each other?

The definition of the lithosphere is based on how earth materials behave, so it includes the crust and the uppermost mantle, which are both brittle. Since it is rigid and brittle, when stresses act on the lithosphere, it breaks. This is what we experience as an earthquake.

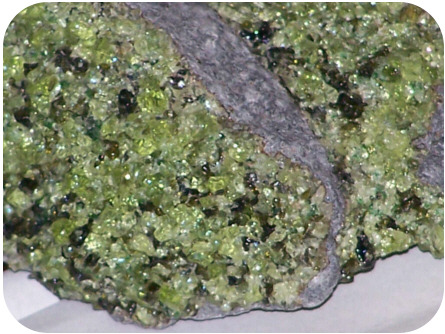

The two most important things about the mantle are: (1) it is made of solid rock, and (2) it is hot. Scientists know that the mantle is made of rock based on evidence from seismic waves, heat flow, and meteorites. The properties fit the ultramafic rock peridotite, which is made of the iron- and magnesium-rich silicate minerals ( Figure below ). Peridotite is rarely found at Earth's surface.

Figure 6.7

Peridotite is formed of crystals of olivine (green) and pyroxene (black).

Scientists know that the mantle is extremely hot because of the heat flowing outward from it and because of its physical properties.

Heat flows in two different ways within the Earth:

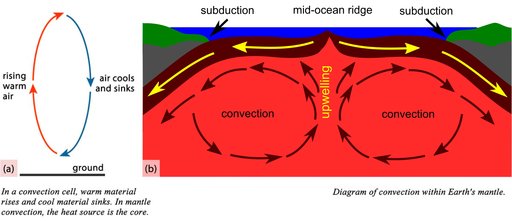

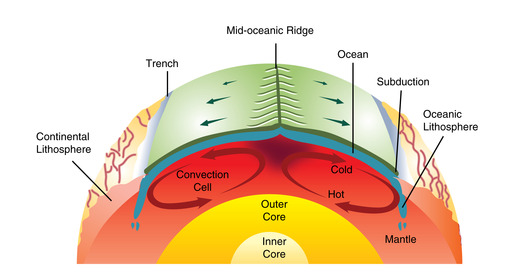

Convection in the mantle is the same as convection in a pot of water on a stove. Convection currents within Earth's mantle form as material near the core heats up. As the core heats the bottom layer of mantle material, particles move more rapidly, decreasing its density and causing it to rise. The rising material begins the convection current. When the warm material reaches the surface, it spreads horizontally. The material cools because it is no longer near the core. It eventually becomes cool and dense enough to sink back down into the mantle. At the bottom of the mantle, the material travels horizontally and is heated by the core. It reaches the location where warm mantle material rises, and the mantle convection cell is complete ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.8

At the planet’s center lies a dense metallic core. Scientists know that the core is metal because:

Figure 6.9

An iron meteorite is the closest thing to the Earth

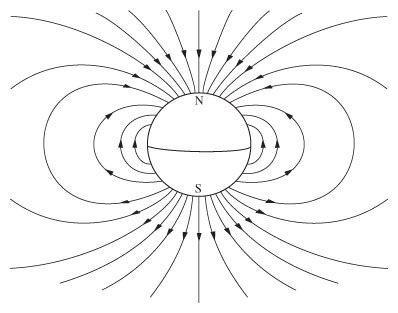

If Earth's core were not metal, the planet would not have a magnetic field. Metals such as iron are magnetic, but rock, which makes up the mantle and crust, is not.

Scientists know that the outer core is liquid and the inner core is solid because:

The heat that keeps the outer core from solidifying is produced by the breakdown of radioactive elements in the inner core.

The continental drift hypothesis was developed in the early part of the 20 th century, mostly by Alfred Wegener. Wegener said that continents move around on Earth’s surface and that they were once joined together as a single supercontinent. While Wegener was alive, scientists did not believe that the continents could move.

Find a map of the continents and cut each one out. Better yet, use a map where the edges of the continents show the continental shelf. That’s the true size and shape of a continent. Can you fit the pieces together? The easiest link is between the eastern Americas and western Africa and Europe, but the rest can fit together too ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.10

The continents fit together like pieces of a puzzle. This is how they looked 250 million years ago.

Alfred Wegener proposed that the continents were once united into a single supercontinent named Pangaea, meaning all earth in ancient Greek. He suggested that Pangaea broke up long ago and that the continents then moved to their current positions. He called his hypothesis continental drift.

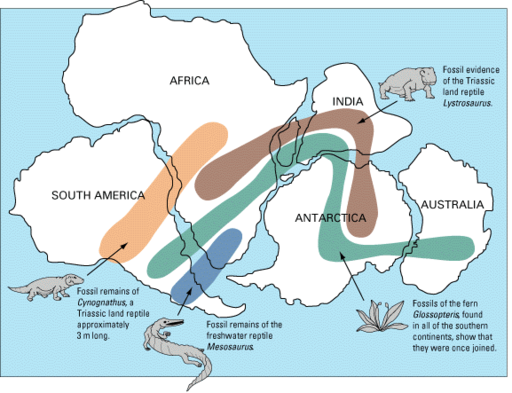

Besides the way the continents fit together, Wegener and his supporters collected a great deal of evidence for the continental drift hypothesis.

Figure 6.11

The similarities between the Appalachian and the eastern Greenland mountain ranges are evidences for the continental drift hypothesis.

Figure 6.12

Wegener used fossil evidence to support his continental drift hypothesis. The fossils of these organisms are found on lands that are now far apart.

An animation showing that Earth’s climate belts remain in roughly the same position while the continents move is seen here: http://www.scotese.com/paleocli.htm .

An animation showing how the continents split up can be found here: http://www.exploratorium.edu/origins/antarctica/ideas/gondwana2.html .

Although Wegener’s evidence was sound, most geologists at the time rejected his hypothesis of continental drift. Why do you think they did not accept continental drift?

Scientists argued that there was no way to explain how solid continents could plow through solid oceanic crust. Wegener’s idea was nearly forgotten until technological advances presented even more evidence that the continents moved and gave scientists the tools to develop a mechanism for Wegener’s drifting continents.

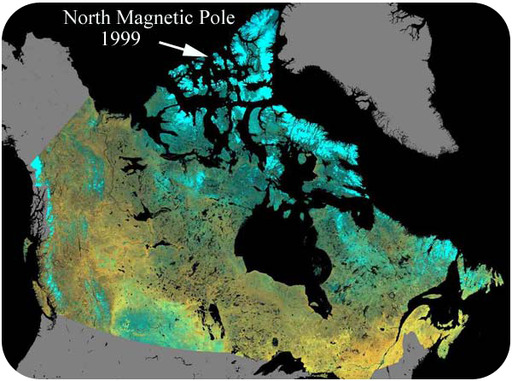

Puzzling new evidence came in the 1950s from studies on the Earth's magnetic history ( Figure below ). Scientists used magnetometers , devices capable of measuring the magnetic field intensity, to look at the magnetic properties of rocks in many locations.

Figure 6.13

Magnetite crystals are like tiny magnets that point to the north magnetic pole as they crystallize from magma. The crystals record both the direction and strength of the magnetic field at the time. The direction is known as the field’s magnetic polarity.

Geologists noted important things about the magnetic polarity of different aged rocks on the same continent:

Figure 6.14

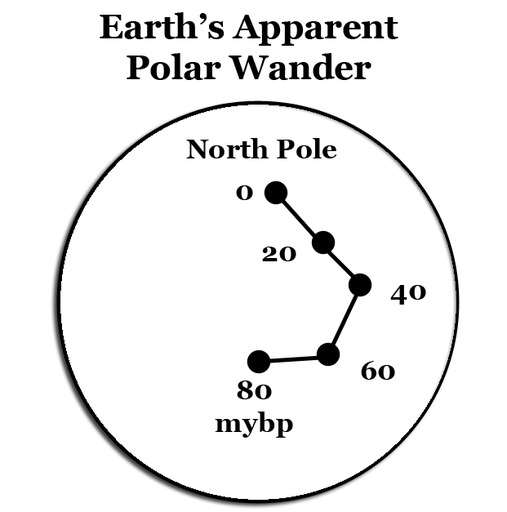

In other words, although the magnetite crystals were pointing to the magnetic north pole, the location of the pole seemed to wander. Scientists were amazed to find that the north magnetic pole changed location through time ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.15

The location of the north magnetic north pole 80 million years before present (mybp), then 60, 40, 20, and now.

There are three possible explanations for this:

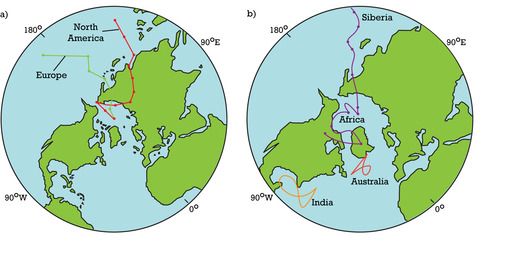

Geologists noted that for rocks of the same age but on different continents, the little magnets pointed to different magnetic north poles.

The scientists looked again at the three possible explanations. Only one can be correct. If the continents had remained fixed while the north magnetic pole moved, there must have been two separate north poles. Since there is only one north pole today, the only reasonable explanation is that the north magnetic pole has remained fixed but that the continents have moved.

To test this, geologists fitted the continents together as Wegener had done. It worked! There has only been one magnetic north pole and the continents have drifted ( Figure below ). They named the phenomenon of the magnetic pole that seemed to move but actually did not apparent polar wander.

Figure 6.16

On the left: The apparent north pole for Europe and North America if the continents were always in their current locations. The two paths merge into one if the continents are allowed to drift.

This evidence for continental drift gave geologists renewed interest in understanding how continents could move about on the planet’s surface.

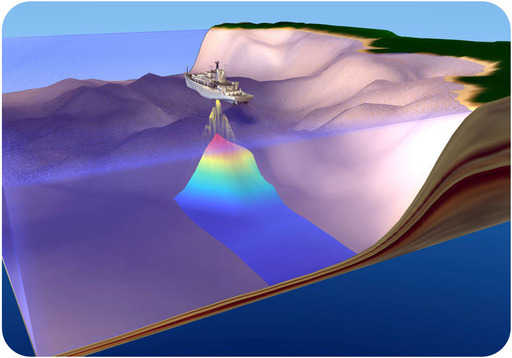

World War II gave scientists the tools to find the mechanism for continental drift that had eluded Wegener. Maps and other data gathered during the war allowed scientists to develop the seafloor spreading hypothesis. This hypothesis traces oceanic crust from its origin at a mid-ocean ridge to its destruction at a deep sea trench and is the mechanism for continental drift.

During World War II, battleships and submarines carried echo sounders to locate enemy submarines ( Figure below ). Echo sounders produce sound waves that travel outward in all directions, bounce off the nearest object, and then return to the ship. By knowing the speed of sound in seawater, scientists calculate the distance to the object based on the time it takes for the wave to make a round-trip. During the war, most of the sound waves ricocheted off the ocean bottom.

Figure 6.17

This echo sounder has many beams and creates a three dimensional map of the seafloor. Early echo sounders had a single beam and created a line of depth measurements.

This animation shows how sound waves are used to create pictures of the sea floor and ocean crust: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_sonar.html .

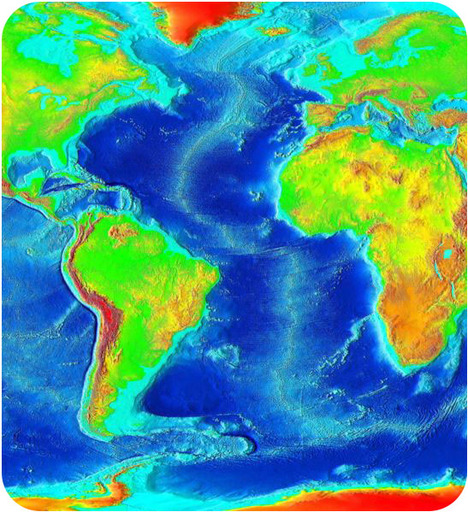

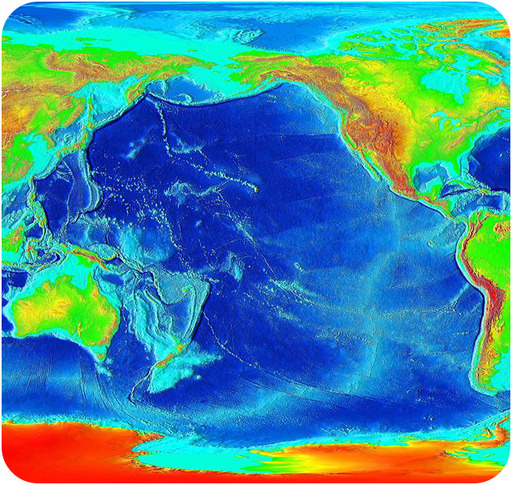

After the war, scientists pieced together the ocean depths to produce bathymetric maps, which reveal the features of the ocean floor as if the water were taken away. Even scientist were amazed that the seafloor was not completely flat ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.18

A modern map of the southeastern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

The major features of the ocean basins and their colors on the map in Figure above include:

A map of the ocean floor with features drawn in is found here: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_midoceanridges.html.

When they first observed these bathymetric maps, scientists wondered what had formed these features.

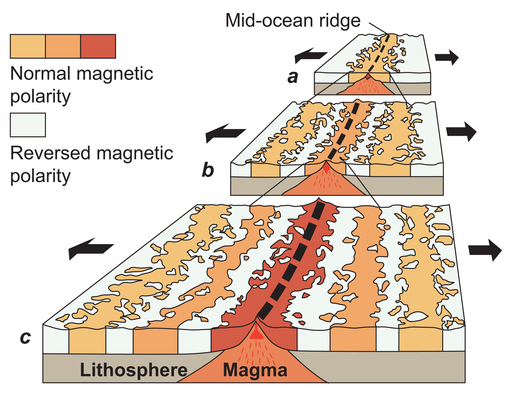

Sometimes -- no one really knows why -- the magnetic poles switch positions. North becomes south and south becomes north.

During WWII, magnetometers attached to ships to search for submarines located an astonishing feature: the normal and reversed magnetic polarity of seafloor basalts creates a pattern.

Figure 6.19

Magnetic polarity is normal at the ridge crest but reversed in symmetrical patterns away from the ridge center. This normal and reversed pattern continues across the seafloor.

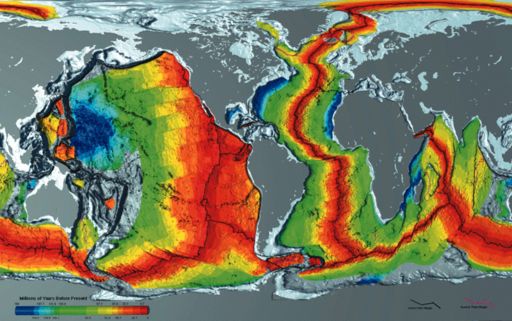

Figure 6.20

Seafloor is youngest at the mid-ocean ridges and becomes progressively older with distance from the ridge.

The characteristics of the rocks and sediments change with distance from the ridge axis as seen in the Table below .

Table 6.2

| Rock ages | Sediment thickness | Crust thickness | Heat flow | |

| At ridge axis | youngest | none | thinnest | hottest |

| With distance from axis | becomes older | becomes thicker | becomes thicker | becomes cooler |

A map of sediment thickness is found here: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_sedimentthickness.html .

The oldest seafloor is near the edges of continents or deep sea trenches and is less than 180 million years old ( Figure above ). Since the oldest ocean crust is so much younger than the oldest continental crust, scientists realized that seafloor was being destroyed in a relatively short time.

This 65 minute video explains “The Role of Paleomagnetism in the Evolution of Plate Tectonic Theory”: http://online.wr.usgs.gov/calendar/2004/jul04.html .

Scientists brought these observations together in the early 1960s to create the seafloor spreading hypothesis. In this hypothesis, hot buoyant mantle rises up a mid-ocean ridge, causing the ridge to rise upward ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.21

Magma at the mid-ocean ridge creates new seafloor.

The hot magma at the ridge erupts as lava that forms new seafloor. When the lava cools, the magnetite crystals take on the current magnetic polarity. As more lava erupts, it pushes the seafloor horizontally away from ridge axis.

These animations show the creation of magnetic stripes of normal and reversed polarity at a mid-ocean ridge: http://www.nature.nps.gov/GEOLOGY/usgsnps/animate/A49.gif ; http://www.nature.nps.gov/GEOLOGY/usgsnps/animate/A55.gif .

The magnetic stripes continue across the seafloor.

Seafloor spreading is the mechanism for Wegener’s drifting continents. Convection currents within the mantle take the continents on a conveyor-belt ride of oceanic crust that over millions of years takes them around the planet’s surface.

The breakup of Pangaea by seafloor spreading is seen in this animation: http://www.scotese.com/sfsanim.htm .

The breakup of Pangaea with a focus on the North Atlantic: http://www.scotese.com/natlanim.htm .

An animation of the breakup of Pangaea focused on the Pacific Ocean: http://www.scotese.com/pacifanim.htm .

Seafloor spreading is the topic of this Discovery Education video: http://video.yahoo.com/watch/1595570/5390151 .

The history of the seafloor spreading hypothesis and the evidence that was collected to develop it are the subject of this video

(3a)

:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6CsTTmvX6mc&feature=rec-LGOUT-exp_fresh+div-1r-2

(8:05).

When the concept of seafloor spreading came along, scientists recognized that it was the mechanism to explain how continents could move around Earth’s surface. Like the scientists before us, we will now merge the ideas of continental drift and seafloor spreading into the theory of plate tectonics.

Continental drift and the mechanism of seafloor spreading create plate tectonics: http://video.yahoo.com/watch/1595682/5390276 .

Seafloor and continents move around on Earth’s surface, but what is actually moving? What portion of the Earth makes up the “plates” in plate tectonics? This question was also answered because of technology developed during war times - in this case, the Cold War. The plates are made up of the lithosphere.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, scientists set up seismograph networks to see if enemy nations were testing atomic bombs. These seismographs also recorded all of the earthquakes around the planet. The seismic records could be used to locate an earthquake’s epicenter , the point on Earth’s surface directly above the place where the earthquake occurs.

Earthquake epicenters outline the plates. Mid-ocean ridges, trenches, and large faults mark the edges of the plates, and this is where earthquakes occur ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.22

Earthquakes outline the plates.

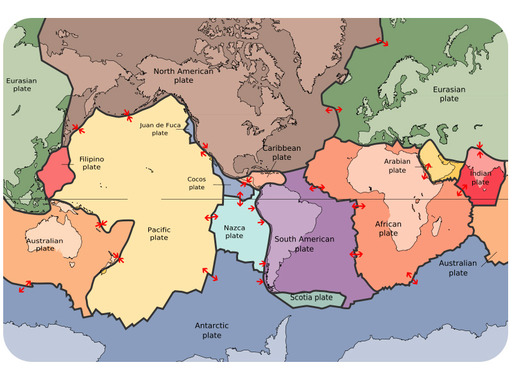

The lithosphere is divided into a dozen major and several minor plates ( Figure below ). The plates’ edges can be drawn by connecting the dots that mark earthquakes' epicenters. A single plate can be made of all oceanic lithosphere or all continental lithosphere, but nearly all plates are made of a combination of both.

Figure 6.23

The lithospheric plates and their names. The arrows show whether the plates are moving apart, moving together, or sliding past each other.

Movement of the plates over Earth's surface is termed plate tectonics . Plates move at a rate of a few centimeters a year, about the same rate fingernails grow.

If seafloor spreading drives the plates, what drives seafloor spreading? Picture two convection cells side-by-side in the mantle, similar to the illustration in Figure below .

Figure 6.24

Mantle convection drives plate tectonics. Hot material rises at mid-ocean ridges and sinks at deep sea trenches, which keeps the plates moving along the Earth

Mantle convection is shown in these animations:

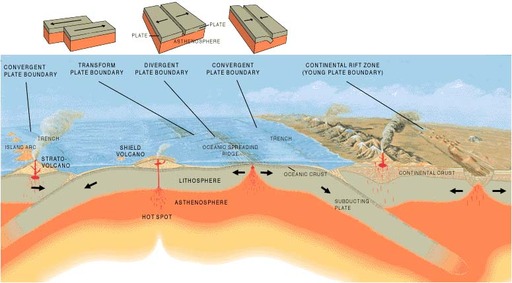

Plate boundaries are the edges where two plates meet. Most geologic activities, including volcanoes, earthquakes, and mountain building, take place at plate boundaries. How can two plates move relative to each other?

The type of plate boundary and the type of crust found on each side of the boundary determines what sort of geologic activity will be found there.

Plates move apart at mid-ocean ridges where new seafloor forms. Between the two plates is a rift valley. Lava flows at the surface cool rapidly to become basalt, but deeper in the crust, magma cools more slowly to form gabbro. So the entire ridge system is made up of igneous rock that is either extrusive or intrusive. Earthquakes are common at mid-ocean ridges since the movement of magma and oceanic crust results in crustal shaking. The vast majority of mid-ocean ridges are located deep below the sea ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.25

(a) Iceland is the one location where the ridge is located on land: the Mid-Atlantic Ridge separates the North American and Eurasian plates; (b) The rift valley in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge on Iceland.

USGS animation of divergent plate boundary at mid-ocean ridge: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/animations/animation.php?flash_title=Divergent+Boundary&flash_file=divergent&flash_width=500&flash_height=200 .

Divergent plate boundary animation: http://www.iris.edu/hq/files/programs/education_and_outreach/aotm/11/AOTM_09_01_Divergent_480.mov .

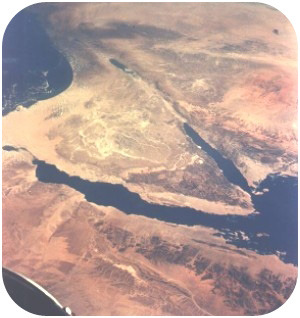

Can divergent plate boundaries occur within a continent? What is the result? In continental rifting ( Figure below ), magma rises beneath the continent, causing it to become thinner, break, and ultimately split apart. New ocean crust erupts in the void, creating an ocean between continents.

Figure 6.26

The Arabian, Indian, and African plates are rifting apart, forming the Great Rift Valley in Africa. The Dead Sea fills the rift with seawater.

When two plates converge, the result depends on the type of lithosphere the plates are made of. No matter what, smashing two enormous slabs of lithosphere together results in magma generation and earthquakes.

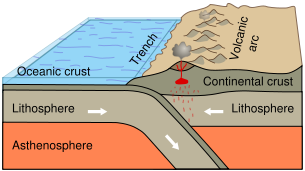

Ocean-continent : When oceanic crust converges with continental crust, the denser oceanic plate plunges beneath the continental plate. This process, called subduction , occurs at the oceanic trenches ( Figure below ). The entire region is known as a subduction zone . Subduction zones have a lot of intense earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The subducting plate causes melting in the mantle. The magma rises and erupts, creating volcanoes. These coastal volcanic mountains are found in a line above the subducting plate ( Figure below ). The volcanoes are known as a continental arc .

Figure 6.27

Subduction of an oceanic plate beneath a continental plate causes earthquakes and forms a line of volcanoes known as a continental arc.

The movement of crust and magma causes earthquakes. A map of earthquake epicenters at subduction zones is found here: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_earthquakessubduction.html .

This animation shows the relationship between subduction of the lithosphere and creation of a volcanic arc: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_subduction.html .

Figure 6.28

(a) At the trench lining the western margin of South America, the Nazca plate is subducting beneath the South American plate, resulting in the Andes Mountains (brown and red uplands); (b) Convergence has pushed up limestone in the Andes Mountains where volcanoes are common.

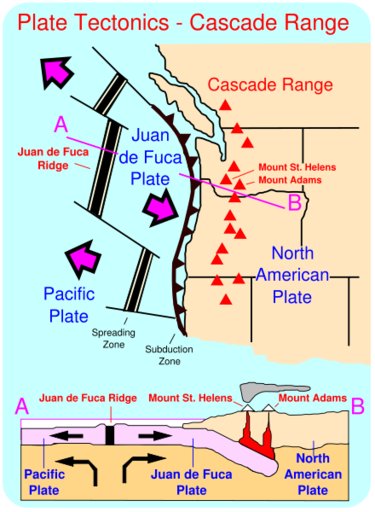

The volcanoes of northeastern California—Lassen Peak, Mount Shasta, and Medicine Lake volcano—along with the rest of the Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest are the result of subduction of the Juan de Fuca plate beneath the North American plate ( Figure below ). The Juan de Fuca plate is created by seafloor spreading just offshore at the Juan de Fuca ridge.

Figure 6.29

The Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest are a continental arc.

If the magma at a continental arc is felsic, it may be too viscous (thick) to rise through the crust. The magma will cool slowly to form granite or granodiorite. These large bodies of intrusive igneous rocks are called batholiths , which may someday be uplifted to form a mountain range ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.30

The Sierra Nevada batholith cooled beneath a volcanic arc roughly 200 million years ago. The rock is well exposed here at Mount Whitney. Similar batholiths are likely forming beneath the Andes and Cascades today.

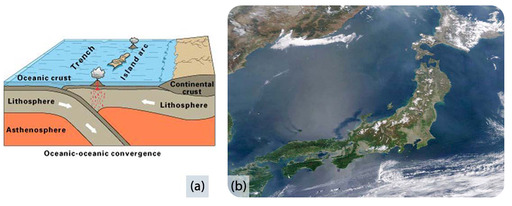

Ocean-ocean : When two oceanic plates converge, the older, denser plate will subduct into the mantle. An ocean trench marks the location where the plate is pushed down into the mantle. The line of volcanoes that grows on the upper oceanic plate is an island arc . Do you think earthquakes are common in these regions ( Figure below )?

Figure 6.31

(a) Subduction of an ocean plate beneath an ocean plate results in a volcanic island arc, an ocean trench and many earthquakes. (b) Japan is an arc-shaped island arc composed of volcanoes off the Asian mainland, as seen in this satellite image.

An animation of an ocean continent plate boundary is seen here: http://www.iris.edu/hq/files/programs/education_and_outreach/aotm/11/AOTM_09_01_Convergent_480.mov .

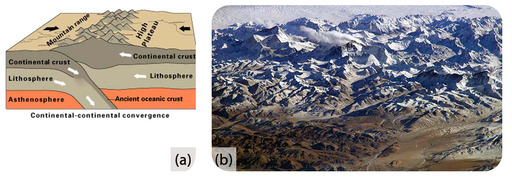

Continent-continent : Continental plates are too buoyant to subduct. What happens to continental material when it collides? Since it has nowhere to go but up, this creates some of the world’s largest mountains ranges ( Figure below ). Magma cannot penetrate this thick crust so there are no volcanoes, although the magma stays in the crust. Metamorphic rocks are common because of the stress the continental crust experiences. With enormous slabs of crust smashing together, continent-continent collisions bring on numerous and large earthquakes.

Figure 6.32

(a) In continent-continent convergence, the plates push upward to create a high mountain range. (b) The world

A short animation of the Indian Plate colliding with the Eurasian Plate: http://www.scotese.com/indianim.htm .

An animation of the Himalaya rising: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ep2_axAA9Mw&NR=1 .

The Appalachian Mountains are the remnants of a large mountain range that was created when North America rammed into Eurasia about 250 million years ago.

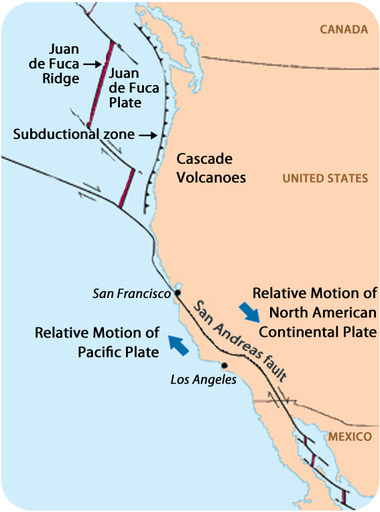

Transform plate boundaries are seen as transform faults , where two plates move past each other in opposite directions. Transform faults on continents bring massive earthquakes ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.33

At the San Andreas Fault in California, the Pacific Plate is sliding northeast relative to the North American plate, which is moving southwest. At the northern end of the picture, the transform boundary turns into a subduction zone.

California is very geologically active. What are the three major plate boundaries in or near California ( Figure below )?

Figure 6.34

This map shows the three major plate boundaries in or near California.

A brief review of the three types of plate boundaries and the structures that are found there is the subject of this wordless video

(3b)

:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifke1GsjNN0

(4:50).

Geologists know that Wegener was right because the movements of continents explain so much about the geology we see. Most of the geologic activity that we see on the planet today is because of the interactions of the moving plates.

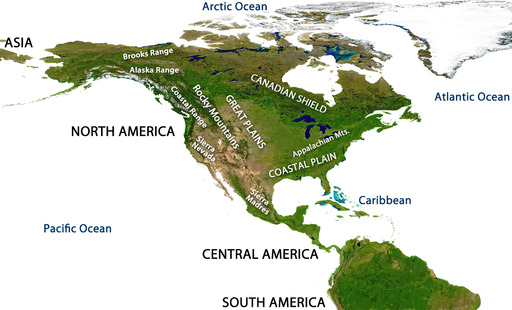

In the map of North America ( Figure below ), where are the mountain ranges located? Using what you have learned about plate tectonics, try to answer the following questions:

Figure 6.35

Mountain ranges of North America.

Remember that Wegener used the similarity of the mountains on the west and east sides of the Atlantic as evidence for his continental drift hypothesis. The Appalachian mountains formed at a convergent plate boundary as Pangaea came together ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.36

About 200 million years ago, the Appalachian Mountains of eastern North America were probably once as high as the Himalaya, but they have been weathered and eroded significantly since the breakup of Pangaea.

Before Pangaea came together, the continents were separated by an ocean where the Atlantic is now. The proto-Atlantic ocean shrank as the Pacific ocean grew. Currently, the Pacific is shrinking as the Atlantic is growing. This supercontinent cycle is responsible for most of the geologic features that we see and many more that are long gone ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.37

Scientists think that the creation and breakup of a supercontinent takes place about every 500 million years. The supercontinent before Pangaea was Rodinia. A new continent will form as the Pacific ocean disappears.

This animation shows the movement of continents over the past 600 million years beginning with the breakup of Rodinia: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_plate_reconstruction_blakey.html .

A small amount of geologic activity, known as intraplate activity , does not take place at plate boundaries but within a plate instead. Mantle plumes are pipes of hot rock that rise through the mantle. The release of pressure causes melting near the surface to form a hotspot . Eruptions at the hotspot create a volcano. Hotspot volcanoes are found in a line ( Figure below ). Can you figure out why? Hint: The youngest volcano sits above the hotspot and volcanoes become older with distance from the hotspot.

An animation of the creation of a hotspot chain is seen here: http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_hawaii.html .

Figure 6.38

The Hawaiian Islands are a beautiful example of a hotspot chain. Kilauea volcano lies above the Hawaiian hotspot. Mauna Loa volcano is older than Kilauea and is still erupting, but at a lower rate. The islands get progressively older to the northwest because they are further from the hotspot. Loihi, the youngest volcano, is still below the sea surface.

Geologists use some hotspot chains to tell the direction and the speed a plate is moving ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.39

The Hawaiian chain continues into the Emperor Seamounts. The bend in the chain was caused by a change in the direction of the Pacific plate 43 million years ago. Using the age and distance of the bend, geologists can figure out the speed of the Pacific plate over the hotspot.

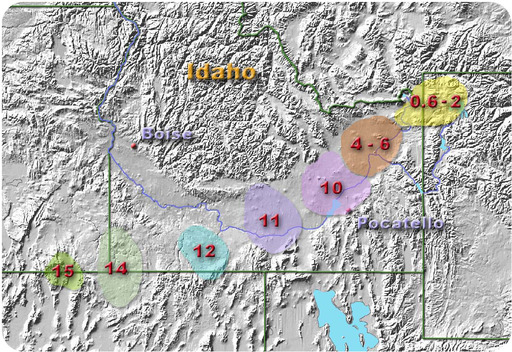

Hotspot magmas rarely penetrate through thick continental crust. One exception is the Yellowstone hotspot ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.40

Volcanic activity above the Yellowstone hotspot on the North American Plate can be traced from 15 million years ago to its present location.

Plate tectonics is the unifying theory of geology. Plate tectonics theory explains why:

Plate tectonic motions affect Earth’s rock cycle, climate, and the evolution of life.

Use this diagram to review this chapter ( Figure below ).

Figure 6.41

Plate boundaries

Opening image courtesy of OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP)/NOAA, http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/htmls/nur04506.htm , and is in the public domain.