Above are two false-color Landsat satellite images of Mount St. Helens and vicinity. The first image is from August 29, 1979. Just months later, in March 1980, the ground began to shake. Red indicates vegetation; patches of lighter color are where the region was logged.

The second image is from September 24, 1980, four months after the large eruption on May 18. The relics of the eruption are everywhere. The mountain’s northern flank has collapsed, leaving a horseshoe shaped crater. Rock and ash have blown over 230 square miles. Dead trees are floating in Spirit Lake and volcanic mudflows clog the rivers. A more recent image shows that vegetation has begun to colonize at the farther reaches of the area affected by the eruption.

Volcanoes are a vibrant manifestation of plate tectonics processes. Volcanoes are common along convergent and divergent plate boundaries. Volcanoes are also found within lithospheric plates away from plate boundaries. Wherever mantle is able to melt, volcanoes may be the result.

Figure 8.1

World map of active volcanoes.

See if you can give a geological explanation for the locations of all the volcanoes in Figure above . What is the Pacific Ring of Fire? Why are the Hawaiian volcanoes located away from any plate boundaries? What is the cause of the volcanoes along the mid-Atlantic ridge?

Volcanoes erupt because mantle rock melts. This is the first stage in creating a volcano. Remember from the chapter “Rocks” that mantle may melt if temperature rises, pressure lowers, or water is added. Be sure to think about how melting occurs in each of the following volcanic settings.

Why does melting occur at convergent plate boundaries? The subducting plate heats up as it sinks into the mantle. Also, water is mixed in with the sediments lying on top of the subducting plate. This water lowers the melting point of the mantle material, which increases melting. Volcanoes at convergent plate boundaries are found all along the Pacific Ocean basin, primarily at the edges of the Pacific, Cocos, and Nazca plates. Trenches mark subduction zones, although only the Aleutian Trench and the Java Trench appear on the map above ( Figure above ).

Remember your plate tectonics knowledge. Large earthquakes are extremely common along convergent plate boundaries. Since the Pacific Ocean is rimmed by convergent and transform boundaries, about 80% of all earthquakes strike around the Pacific Ocean basin ( Figure below ). Why are 75% of the world’s volcanoes found around the Pacific basin? Of course, these volcanoes are caused by the abundance of convergent plate boundaries around the Pacific.

Figure 8.2

The Pacific Ring of Fire is where the majority of the volcanic activity on the Earth occurs.

A description of the Pacific Ring of Fire along western North America is a description of the plate boundaries.

The Cascades are shown on this interactive map with photos and descriptions of each of the volcanoes: http://www.iris.edu/hq/files/programs/education_and_outreach/aotm/interactive/6.Volcanoes4Rollover.swf .

A hot spot beneath Hawaii, the origin of the voluminous lava produced by the shield volcano Kilauea can be viewed here

(3f)

:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byJp5o49IF4&feature=related

(2:06).

Why does melting occur at divergent plate boundaries? Hot mantle rock rises where the plates are moving apart. This releases pressure on the mantle, which lowers its melting temperature. Lava erupts through long cracks in the ground, or fissures.

Footage of Undersea Volcanic Eruptions is seen in National Geographic Videos, Environment Video, Habitat, Ocean section: http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/player/environment/ .

Volcanoes erupt at mid-ocean ridges, such as the Mid-Atlantic ridge, where seafloor spreading creates new seafloor in the rift valleys. Where a hotspot is located along the ridge, such as at Iceland, volcanoes grow high enough to create islands ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.3

A volcanic eruption at Surtsey, a small island near Iceland.

Eruptions are found at divergent plate boundaries as continents break apart. The volcanoes in Figure below are in the East African Rift between the African and Arabian plates.

Figure 8.4

Mount Gahinga and Mount Muhabura in the East African Rift valley.

Although most volcanoes are found at convergent or divergent plate boundaries, intraplate volcanoes are found in the middle of a tectonic plate. Why is there melting at these locations? The Hawaiian Islands are the exposed peaks of a great chain of volcanoes that lie on the Pacific plate. These islands are in the middle of the Pacific plate. The youngest island sits directly above a column of hot rock called a mantle plume. As the plume rises through the mantle, pressure is released and mantle melts to create a hotspot ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.5

(a) The Society Islands formed above a hotspot that is now beneath Mehetia and two submarine volcanoes. (b) The satellite image shows how the islands become smaller and coral reefs became more developed as the volcanoes move off the hotspot and grow older.

Earth is home to about 50 known hot spots. Most of these are in the oceans because they are better able to penetrate oceanic lithosphere to create volcanoes. The hotspots that are known beneath continents are extremely large, such as Yellowstone ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.6

Prominent hotspots of the world.

How would you be able to tell hotspot volcanoes from island arc volcanoes? At island arcs, the volcanoes are all about the same age. By contrast, at hotspots the volcanoes are youngest at one end of the chain and oldest at the other.

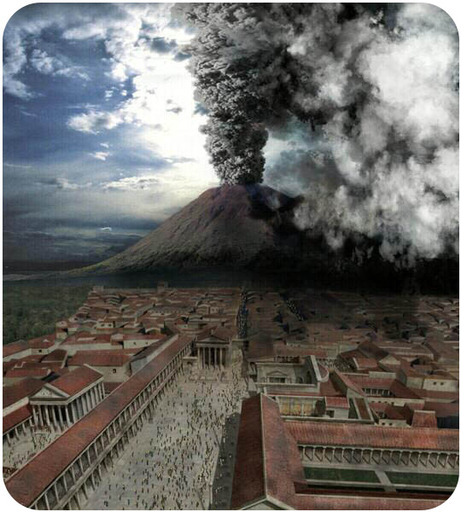

This incredible explosive eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Italy in A.D. 79 is an example of a composite volcano that forms as the result of a convergent plate boundary

(3f)

:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1u1Ys4m5zY4&feature=related

(1:53).

In 1980, Mount St. Helens blew up in the costliest and deadliest volcanic eruption in United States history. The eruption killed 57 people, destroyed 250 homes and swept away 47 bridges ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.7

Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980.

Mt. St. Helens still has minor earthquakes and eruptions. The volcano now has a horseshoe-shaped crater with a lava dome inside. The dome is formed of viscous lava that oozes into place.

Volcanoes do not always erupt in the same way. Each volcanic eruption is unique, differing in size, style, and composition of erupted material. One key to what makes the eruption unique is the chemical composition of the magma that feeds a volcano, which determines (1) the eruption style, (2) the type of volcanic cone that forms, and (3) the composition of rocks that are found at the volcano.

Remember from the Rocks chapter that different minerals within a rock melt at different temperatures. The amount of partial melting and the composition of the original rock determine the composition of the magma. Magma collects in magma chambers in the crust at 160 kilometers (100 miles) beneath the surface.

The words that describe composition of igneous rocks also describe magma composition.

Figure 8.8

Honey flows slowly. It is more viscous than water.

Viscosity determines what the magma will do. Mafic magma is not viscous and will flow easily to the surface. Felsic magma is viscous and does not flow easily. Most felsic magma will stay deeper in the crust and will cool to form igneous intrusive rocks such as granite and granodiorite. If felsic magma rises into a magma chamber, it may be too viscous to move and so it gets stuck. Dissolved gases become trapped by thick magma. The magma churns in the chamber and the pressure builds.

The type of magma in the chamber determines the type of volcanic eruption. Although the two major kinds of eruptions – explosive and effusive - are described in this section, there is an entire continuum of eruption types. Which magma composition do you think leads to each type?

A large explosive eruption creates even more devastation than the force of the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki at the end of World War II in which more than 40,000 people died. A large explosive volcanic eruption is 10,000 times as powerful. Felsic magmas erupt explosively. Hot, gas-rich magma churns within the chamber. The pressure becomes so great that the magma eventually breaks the seal and explodes, just like when a cork is released from a bottle of champagne. Magma, rock, and ash burst upward in an enormous explosion. The erupted material is called tephra ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.9

Ash and gases create a mushroom cloud above Mt. Redoubt in Alaska, 1989. The cloud reached 45,000 feet and caught a Boeing 747 in its plume.

Scorching hot tephra, ash, and gas may speed down the volcano’s slopes at 700 km/h (450 mph) as a pyroclastic flow. Pyroclastic flows knock down everything in their path. The temperature inside a pyroclastic flow may be as high as 1,000 o C (1,800 o F) ( Figure below. ).

Figure 8.10

(a) An explosive eruption from the Mayon Volcano in the Philippines in 1984. Ash flies upward into the sky and pyroclastic flows pour down the mountainside. (b) The end of a pyroclastic flow at Mount St. Helens.

A pyroclastic flow at Montserrat volcano is seen in this video: http://faculty.gg.uwyo.edu/heller/SedMovs/Sed%20Movie%20files/PyroclasticFlow.MOV .

Prior to the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980, the Lassen Peak eruption on May 22, 1915, was the most recent Cascades eruption. A column of ash and gas shot 30,000 feet into the air. This triggered a high-speed pyroclastic flow, which melted snow and created a volcanic mudflow known as a lahar . Lassen Peak currently has geothermal activity and could erupt explosively again. Mt. Shasta, the other active volcano in California, erupts every 600 to 800 years. An eruption would most likely create a large pyroclastic flow, and probably a lahar. Of course, Mt. Shasta could explode and collapse like Mt. Mazama in Oregon ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.11

Crater Lake fills the caldera of the collapsed Mt. Mazama, which erupted with 42 times more power than Mount St. Helens in 1980. The bathymetry of the lake shows volcanic features such as cinder cones.

Volcanic gases can form poisonous and invisible clouds in the atmosphere. These gases may contribute to environmental problems such as acid rain and ozone destruction. Particles of dust and ash may stay in the atmosphere for years, disrupting weather patterns and blocking sunlight ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.12

The ash plume from Eyjafjallaj

Mafic magma creates gentler effusive eruptions . Although the pressure builds enough for the magma to erupt, it does not erupt with the same explosive force as felsic magma. People can usually be evacuated before an effusive eruption, so they are much less deadly. Magma pushes toward the surface through fissures. Eventually, the magma reaches the surface and erupts through a vent ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.13

In effusive eruptions, lava flows readily, producing rivers of molten rock.

Low-viscosity lava flows down mountainsides. Differences in composition and where the lavas erupt result in three types of lava flow coming from effusive eruptions ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.14

(a) A

Although effusive eruptions rarely kill anyone, they can be destructive. Even when people know that a lava flow is approaching, there is not much anyone can do to stop it from destroying a building or road ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.15

A road is overrun by an eruption at Kilauea volcano in Hawaii.

Volcanologists attempt to forecast volcanic eruptions, but this has proven to be nearly as difficult as predicting an earthquake. Many pieces of evidence can mean that a volcano is about to erupt, but the time and magnitude of the eruption are difficult to pin down. This evidence includes the history of previous volcanic activity, earthquakes, slope deformation, and gas emissions.

A volcano’s history -- how long since its last eruption and the time span between its previous eruptions -- is a good first step to predicting eruptions. Which of these categories does the volcano fit into?

Figure 8.16

Mount Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii in 79 AD. Fortunately this volcano is dormant because the region is now much more heavily populated.

Active and dormant volcanoes are heavily monitored, especially in populated areas.

Moving magma shakes the ground, so the number and size of earthquakes increases before an eruption. A volcano that is about to erupt may produce a sequence of earthquakes. Scientists use seismographs that record the length and strength of each earthquake to try to determine if an eruption is imminent.

Magma and gas can push the volcano’s slope upward. Most ground deformation is subtle and can only be detected by tiltmeters, which are instruments that measure the angle of the slope of a volcano. But ground swelling may sometimes create huge changes in the shape of a volcano. Mount St. Helens grew a bulge on its north side before its 1980 eruption. Ground swelling may also increase rock falls and landslides.

Gases may be able to escape a volcano before magma reaches the surface. Scientists measure gas emissions in vents on or around the volcano. Gases, such as sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ), carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), hydrochloric acid (HCl), and even water vapor can be measured at the site ( Figure below ) or, in some cases, from a distance using satellites. The amounts of gases and their ratios are calculated to help predict eruptions.

Figure 8.17

Scientists monitoring gas emissions at Mount St. Helens.

Some gases can be monitored using satellite technology ( Figure below ). Satellites also monitor temperature readings and deformation. As technology improves, scientists are better able to detect changes in a volcano accurately and safely.

Figure 8.18

An Earth-Observation Satellite before launch.

Since volcanologists are usually uncertain about an eruption, officials may not know whether to require an evacuation. If people are evacuated and the eruption doesn’t happen, the people will be displeased and less likely to evacuate the next time there is a threat of an eruption. The costs of disrupting business are great. However, scientists continue to work to improve the accuracy of their predictions.

1. What are the two basic types of volcanic eruptions?

2. Several hundred years ago, a volcano erupted near the city of Pompeii, Italy ( Figure below ). Archaeologists have found the remains of people embracing each other, suffocated by ash and rock that covered everything. What type of eruption must have this been?

Figure 8.19

Pompeii the last day.

3. What is pyroclastic material?

4. Name three substances that have low viscosity and three that have high viscosity.

5. Why might the addition of water make an eruption more explosive?

6. What are three names for non-explosive lava?

7. What factors are considered in predicting volcanic eruptions?

8. Why is predicting a volcanic eruption so important?

9. Given that astronomers are far away from the planets they study, what evidence might they look for to determine the composition of a planet on which a volcano is found?

A volcano is a vent through which molten rock and gas escape from a magma chamber. Volcanoes differ in many features such as height, shape, and slope steepness. Some volcanoes are tall cones and others are just cracks in the ground ( Figure below ). As you might expect, the shape of a volcano is related to the composition of its magma.

Figure 8.20

Mount St. Helens was a beautiful, classic, cone-shaped volcano. The volcano

Composite volcanoes are made of felsic to intermediate rock. The viscosity of the lava means that eruptions at these volcanoes are often explosive ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.21

Mt. Fuji, the highest mountain in Japan, is a dormant composite volcano.

The viscous lava cannot travel far down the sides of the volcano before it solidifies, which creates the steep slopes of a composite volcano. Viscosity also causes some eruptions to explode as ash and small rocks. The volcano is constructed layer by layer, as ash and lava solidify, one upon the other ( Figure below ). The result is the classic cone shape of composite volcanoes.

Figure 8.22

A cross section of a composite volcano reveals alternating layers of rock and ash: (1) magma chamber, (2) bedrock, (3) pipe, (4) ash layers, (5) lava layers, (6) lava flow, (7) vent, (8) lava, (9) ash cloud. Frequently there is a large crater at the top from the last eruption.

Shield volcanoes get their name from their shape. Although shield volcanoes are not steep, they may be very large. Shield volcanoes are common at spreading centers or intraplate hot spots ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.23

Mauna Loa Volcano in Hawaii is the largest shield volcano on Earth with a diameter of more than 112 kilometers (70 miles). The volcano forms a significant part of the island of Hawaii.

The lava that creates shield volcanoes is fluid and flows easily. The spreading lava creates the shield shape. Shield volcanoes are built by many layers over time and the layers are usually of very similar composition. The low viscosity also means that shield eruptions are non-explosive.

This

Volcanoes 101

video from National Geographic discusses where volcanoes are found and what their properties come from

(3e)

:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_profilepage&v=uZp1dNybgfc

(3:05).

Cinder cones are the most common type of volcano. A cinder cone has a cone shape, but is much smaller than a composite volcano. Cinder cones rarely reach 300 meters in height but they have steep sides. Cinder cones grow rapidly, usually from a single eruption cycle ( Figure below ). Cinder cones are composed of small fragments of rock, such as pumice, piled on top of one another. The rock shoots up in the air and doesn’t fall far from the vent. The exact composition of a cinder cone depends on the composition of the lava ejected from the volcano. Cinder cones usually have a crater at the summit.

Figure 8.24

In 1943, a Mexican farmer first witnessed a cinder cone erupting in his field. In a year, Paricut

Cinder cones are often found near larger volcanoes ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.25

This Landsat image shows the topography of San Francisco Mountain, an extinct volcano, with many cinder cones near it in northern Arizona. Sunset crater is a cinder cone that erupted about 1,000 years ago.

Supervolcano eruptions are extremely rare in Earth history. It’s a good thing because they are unimaginably large. A supervolcano must erupt more than 1,000 cubic km (240 cubic miles) of material, compared with 1.2 km 3 for Mount St. Helens or 25 km 3 for Mount Pinatubo, a large eruption in the Philippines in 1991. Not surprisingly, supervolcanoes are the most dangerous type of volcano.

Supervolcanoes are a fairly new idea in volcanology. The exact cause of supervolcano eruptions is still debated. However, scientists think that a very large magma chamber erupts entirely in one catastrophic explosion. This creates a huge hole or caldera into which the surface collapses ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.26

The caldera at Santorini in Greece is so large that it can only be seen by satellite.

The largest supervolcano in North America is beneath Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Yellowstone sits above a hotspot that has erupted catastrophically three times: 2.1 million, 1.3 million, and 640,000 years ago. Yellowstone has produced many smaller (but still enormous) eruptions more recently ( Figure below ). Fortunately, current activity at Yellowstone is limited to the region’s famous geysers.

The Old Faithful web cam shows periodic eruptions of Yellowstone’s famous geyser in real time: http://www.nps.gov/archive/yell/oldfaithfulcam.htm.

Figure 8.27

The Yellowstone hotspot has produced enormous felsic eruptions. The Yellowstone caldera collapsed in the most recent super eruption.

Long Valley Caldera, south of Mono Lake in California, is the second largest supervolcano in North America ( Figure below ). Long Valley had an extremely hot and explosive rhyolite about 700,000 years ago. An earthquake swarm in 1980 alerted geologists to the possibility of a future eruption, but the quakes have since calmed down.

Figure 8.28

The hot water that gives Hot Creek, California, its name is heated by hot rock below Long Valley Caldera.

A supervolcano could change life on Earth as we know it. Ash could block sunlight so much that photosynthesis would be reduced and global temperatures would plummet. Volcanic eruptions could have contributed to some of the mass extinctions in our planet’s history. No one knows when the next super eruption will be.

Interesting volcano videos are seen on National Geographic Videos, Environment Video, Natural Disasters, Earthquakes: http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/player/environment/. One interesting one is “Mammoth Mountain,” which explores Hot Creek and the volcanic area it is a part of in California.

Volcanoes are associated with many types of landforms. The landforms vary with the composition of the magma that created them. Hot springs and geysers are also examples of surface features related to volcanic activity.

The most obvious landforms created by lava are volcanoes, most commonly as cinder cones, composite volcanoes, and shield volcanoes. Eruptions also take place through fissures ( Figure below ). The eruptions that created the entire ocean floor are essentially fissure eruptions.

Figure 8.29

A fissure eruption on Mauna Loa in Hawaii travels toward Mauna Kea on the Big Island.

When lava is viscous, it is flows slowly. If there is not enough magma or enough pressure to create an explosive eruption, the magma may form a lava dome. Because it is so thick, the lava does not flow far from the vent. ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.30

Lava domes are large, round landforms created by thick lava that does not travel far from the vent.

Lava flows often make mounds right in the middle of craters at the top of volcanoes, as seen in the Figure below .

Figure 8.31

Lava domes may form in the crater of composite volcanoes as at Mount St. Helens

A lava plateau forms when large amounts of fluid lava flows over an extensive area ( Figure below ). When the lava solidifies, it creates a large, flat surface of igneous rock.

Figure 8.32

Layer upon layer of basalt have created the Columbia Plateau, which covers more than 161,000 square kilometers (63,000 square miles) in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Lava creates new land as it solidifies on the coast or emerges from beneath the water ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.33

Lava flowing into the sea creates new land in Hawaii.

Over time the eruptions can create whole islands. The Hawaiian Islands are formed from shield volcano eruptions that have grown over the last 5 million years ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.34

A 3-D computer generated view of the Big Island of Hawaii with its five volcanoes.

Magma intrusions can create landforms. Shiprock in New Mexico is the neck of an old volcano that has eroded away ( Figure below ).

Figure 8.35

The aptly named Shiprock in New Mexico.

Water sometimes comes into contact with hot rock. The water may emerge at the surface as either a hot spring or a geyser.

Water heated below ground that rises through a crack to the surface creates a hot spring ( Figure below ). The water in hot springs may reach temperatures in the hundreds of degrees Celsius beneath the surface, although most hot springs are much cooler.

Figure 8.36

Even some animals enjoy relaxing in nature's hot tubs.

Geysers are also created by water that is heated beneath the Earth’s surface, but geysers do not bubble to the surface -- they erupt. When water is both superheated by magma and flows through a narrow passageway underground, the environment is ideal for a geyser. The passageway traps the heated water underground, so that heat and pressure can build. Eventually, the pressure grows so great that the superheated water bursts out onto the surface to create a geyser. Figure below .

Conditions are right for the formation of geysers in only a few places on Earth. Of the roughly 1,000 geysers worldwide and about half are found in the United States.

Figure 8.37

Castle Geyser is one of the many geysers at Yellowstone National Park. Castle erupts regularly, but not as frequently or predictably as Old Faithful.

Opening image courtesy of Robert Simmon and NASA's Earth Observatory, http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=43999 , and is in the public domain.