STORY

If the narrative of Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is a muddle, the story has the simplicity and power of myth. El Jefe, a wealthy Mexican rancher, puts a price on the head of the man who impregnated then abandoned his daughter. When two bounty-hunters turn up at a bar-cum-brothel in Mexico City in search of their quarry and question Bennie, the drunken piano player, he sees his chance to get rich. He embarks on a quest to find the wanted man, taking along his girlfriend, Elita, a singer and part-time whore who, he discovers, cuckolded him with Alfredo. She tells Bennie that Alfredo is dead but, to her horror, he decides to try and collect the bounty anyway. When they decide to camp out after a tyre blow-out, they are set upon by a couple of bikers, one of whom tries to rape Elita only to have her respond passionately. Bennie kills both men and despite Elita’s pleas that they give up, he insists they continue. In a rural cemetery, Bennie digs up the body but he is ambushed and buried alive with the murdered Elita. When Bennie rises from the grave, leaving Elita with the decapitated body of her ex-lover, he is a man transformed. After much killing, including the deaths of the Garcia family and the two bounty-hunters, he gets the head back. Now more interested in killing than money, he slaughters El Jefe’s hoods in their hotel room and finds a note in the pocket of a corpse that leads him to El Jefe. Bennie travels to El Jefe’s compound to deliver the head before pulling his gun and, at the urging of the patriarch’s daughter, killing El Jefe. Attempting to flee with the money and the head, Bennie is shot and killed. This tale of greed, murder and madness south of the border consciously echoes John Huston’s classic The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). Peckinpah was a great admirer of Huston (‘compared to Huston, I’m still in seventh grade’ (Murray 2008: 113)) and both films concern themselves with gringo loser anti-heroes seeking their fortune in Mexico. In case we missed this, the connection is made clear when Gig Young’s bounty-hunter gives his name as Fred C. Dobbs, the name of the Humphrey Bogart character in Huston’s film. In a sense, he is Dobbs and so is Bennie: as a bandido says to Bogart in the earlier film: ‘I know you. You’re the guy in the hole.’ This is a world where everyone is Dobbs, the guy in the hole, on the make, soulless, grasping and crazed with greed.

Indeed, it is useful to consider Roger Ebert’s description of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre as ‘a film about a seedy loser driven mad by greed’ (2003) or Louis B. Mayer’s thoughts on the same director’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950): ‘full of nasty, ugly people doing nasty, ugly things’ (quoted in Grobel 1989: 336). Both men could be talking about Peckinpah’s film. But the execution of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Alfredo Garcia differ wildly. Whereas the earlier film is a model of clarity and economy, Peckinpah sacrifices these things and replaces them with a tone which is often uncertain, a streak of black humour that may or may not be intentional and a mood that lurches from the revolting to the poetic and back again. Gabrielle Murray’s description of the film’s ‘strange complexity and haunting lyricism’ (2002) is a good one. Maybe the best example of the film’s sick poetry is when Bennie is driving away from the gun battle with the Garcia family. Muddy from the grave, bleeding from a shovel to the head, he drives his battered car, waving away the stink of rotting flesh, talking to the head over the buzzing of flies. ‘You got jewels in your ears, diamonds up your nose’, he tells it (him? I’m reminded of The Tenant (Roman Polanski, 1976) here, with Polanski’s Trelkovsky musing, ‘If you cut off my head, what do I say: me and my head or me and my body?’). Bennie’s talking to the head may well be another nod to The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, wherein the increasingly unhinged Dobbs talks to himself as the vintage prospector Howard (Walter Huston) tells him, ‘It’s a bad sign when a fella starts talking to himself’. Or to a severed head in a sack.

It is this scrappy quality, the longeurs and the choppy editing that help to give the film its unique power. In his previous films, Peckinpah had shown himself to be a master of pacing and tone. This can be seen in both the oppressive tension of Straw Dogs and the stoned elegy that is Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. But Alfredo Garcia does away with both of those approaches, giving us instead a loose, rambling structure that has a grim, hypnotic pull all of its own. It often seems like two films stitched together. The first is a slow-moving, often uncertain love story with meandering stretches and moments so intense they are hard to watch. The second is a faster, violent neo-western, with splashes of gothic excess and pitch-black humour. This duality has the effect, when combined with the distancing devices the director frequently uses, such as slow-motion and a bewildering number of cuts, of creating a sense of disorientation in the viewer. It’s hard to say how intentional this is. As mentioned, many critics feel Alfredo Garcia is the point at which a talented filmmaker lost the plot, never to get it back, while others consider its weird, alienating effects and tonal shifts to be part of a strategy: Steven Prince talks of the film’s ‘prolonged assault on the normative pleasures viewers look for in narrative cinema’ (1998: 151) while, for Terence Butler, ‘despite the diffuseness of its dream-like setting, Alfredo Garcia succinctly exposes contradictions underlying Peckinpah’s work and the American Dream’ (1979: 92).

AUTOBIOGRAPHY: DRINK AND DISAPPOINTMENT

Strategic device or not, the disorientation on show may well have been Peckinpah’s. The director’s perception of himself as a failure, his seemingly-bottomless well of self-pity and his alcoholism are all important elements in understanding the film. His drinking had long been the stuff of legend but after the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid debacle, it became even more of a problem and he was having regular alcohol-induced blackouts and wild rages. Whenever he stopped, he would smoke a lot of dope. But the drink, the dope, the pills and, from The Killer Elite on, the coke aren’t simply important as the stuff of anecdote: rather, I think they had a marked effect on Peckinpah’s work as well as his personality, and Alfredo Garcia is the point in his career when he was starting to unravel, putting this up on the screen for all to see. Certainly, he often invites this confusion between art and artist: in the documentary feature Passion and Poetry, the director says, ‘all my guts, all my life, everything I am is up there on the screen. It’s all there, everything I am is right there.’ Peckinpah’s drinking has to, I think, be regarded as something inextricably bound up with this film, in much the same way as Hitchcock’s sexual kinks inform Vertigo (1958) and Marnie (1964). The alcohol fuelled two, seemingly contradictory, aspects of his personality that frequently found their way onto the screen: his self-pity and his macho braggadocio. The same duality is also found in John Huston, another legendary drinker, whose films are defined by bluff, macho heroes who talk big but end up engaged in hopeless causes. When Peckinpah says ‘a drunk has dreams, a sober man doesn’t’ (in Bryson 2008: 138), he is not only talking about himself but his alter ego Bennie. Likewise, the director’s glib comment to an interviewer: ‘would you like to know what I really believe? I believe I’ll have another drink’ (in Jenson 2008: 78). Rick Moody suggests that Alfredo Garcia, with its ‘garishness, the half-heartedness of the production values, the fuzzy story and fuzzier characters reminds us that … Peckinpah is among the undisputed poets of alcoholic cinema’ (2009). For Modern Drunkard magazine (‘standing up for your right to get falling down drunk since 1996’), the director is ‘an exemplary drunkard … who knew alcohol. He spoke its language’ (English 2006). Bennie is sentimental and violent, paranoid and inarticulate, unwashed and unpredictable, a far cry from the pisshead poets of Barfly (Barbet Schroeder, 1987), Leaving Las Vegas (Mike Figgis, 1985) and A Love Song for Bobbie Long (Shainee Gabel, 2004).

Early on, Bennie is dismissed as ‘a loser’ and he responds with ‘nobody loses all the time’. But the black joke at the heart of this film is ‘yes, Bennie. Some people do and you are one of them.’ Or are we supposed to regard his shooting of El Jefe as a kind of victory? Is Bennie growing and learning, in a kind of bitter parody of the kind of character arc we see so often in mainstream cinema? His words near the end of the film suggest that might be the case: ‘I coulda died in Mexico City or T. J. and never known what it was all about.’ When we first see him, singing ‘Guantanamera’ for a bunch of tourists, he bids them farewell by suggesting they go out and ‘find the soul of Mexico’. Is this what Bennie does in the end? Does he achieve a sort of enlightenment through all that killing? In interviews to promote the film, Peckinpah describes Alfredo Garcia in just such redemptive terms, calling it ‘a little picture about human dignity’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 146) and suggesting, ‘finally, finally, somebody gets pissed off with all this bull and takes a gun and shoots a lot of people and gets killed. He’s Everyman, Peckinpah’s Everyman’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 275). Steven Prince suggests the ending is ‘a measure of Peckinpah’s displaced and implicit moralism’ (1998: 193). Or is it just a measure of his self-loathing and pessimism? I’m not so sure about this notion of the film as a kind of moral tract. In the screenplay, Bennie escapes after the climactic bloodbath, carrying Al’s head. But Peckinpah couldn’t resist killing him off. The critic Pauline Kael, who knew the director well, discussed his fraught relationship with producers, saying ‘he liked the hopelessness of it all; the role he played was the loser’ (1999).

The notion of the loser is a recurring motif in Peckinpah films. In Junior Bonner (1972), one character asks, ‘If this world is all about winners, what happens to the losers?’ There is a broad streak of self-pity in Peckinpah’s work as well as great compassion for the washed-up, the disillusioned and the past-it. The critic Elvis Mitchell suggests Peckinpah ‘made epics about failure’ while Alex Cox talks of the ‘sadness that the characters have inside them’ (in Weddle 1994: 367). However, this is counterbalanced to some extent by his oft-expressed interest in the work of Robert Ardrey, the screenwriter-turned-self-taught-social anthropologist, who was fashionable in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Polanski was an admirer and Stanley Kubrick often cited Ardrey when defending his A Clockwork Orange against charges of fascism). Ardrey argued that ‘the history of man is written in blood’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 105) with ‘the exquisite pleasure of murder’ (quoted in Weddle 1994: 396) as our primary drive. He illustrated his arguments with evocative, if flowery, observations such as ‘the propensity for violence … exists like a layer of buried molten magma underlying all human topography, seeking unceasingly some important fissure to become the most important of volcanoes’ (quoted in ibid.). Indeed, Ardrey’s conception of man could be applied not just to Peckinpah’s work, but to the director himself:

We were born of risen apes, not fallen angels, and the apes were armed killers besides … The miracle of man is not how far he has sunk but how magnificently he has risen. We are known among the stars for our poetry, not our corpses. (Quoted in Cagin and Dray 1994: 140).

Straw Dogs is clearly influenced by Ardrey: indeed, in 1972 Peckinpah described him as ‘the only prophet alive today’ (in Murray 2008: 103). But the director’s cod-Darwinian pronouncements like ‘everybody seems to think that man is a noble savage. But he’s only an animal, a meat-eating talking animal’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 106) are strikingly at odds with his empathy with and sympathy for life’s losers. During his early career in theatre and television, he was a great admirer of Tennessee Williams, calling him ‘easily America’s greatest playwright’ (quoted in Weddle 1994: 69) and stating ‘I’ve learned more from Williams than from anyone’ (ibid.) Williams’ sensitivity seems at first glance an uneasy influence on ‘Bloody Sam’ but it’s tempting to see, as David Weddle does, Peckinpah’s work as offering a weird synthesis of Ardrey’s savagery and Williams’ compassion. The director seems to admit as much, when he says of Alfredo Garcia, ‘it is about a love story and it is about vengeance’ (in Bryson 2008: 144).

Certainly, a cursory glance at Peckinpah’s public pronouncements would seem to confirm this duality. In interviews, he could be both concerned citizen (‘I’m afraid to walk the streets of New York or Los Angeles’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 275)) and macho boor (‘Somebody asked if I hit women and I said of course I do. I believe in equal rights for women’ (quoted in ibid.)), serious artist (‘The truth, to me as I see it, is more important than entertainment for its own sake’ (quoted in Prince 1998: v)) and chauvinist pig (‘There’s women and there’s pussy’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 275), dismissing feminists as ‘those bull dykes and the crazies in their tennis sneakers and burlap sacks’ (in Murray 2008: 106)). However, Mark Crispin Miller observes how, behind the bluster, many of Peckinpah’s statements find echoes in his films. The director’s comment on pacifism (‘if a man comes up to you and cuts your hand off, you don’t just offer him the other one. Not if you want to go on playing the piano you don’t’) can be seen as a reference to Bennie, first seen playing the piano one-handed (in Miller 1975:17). Like Hitchcock, he constructed a public persona that fed into his films, casting himself as the Holy Fool, part visionary artist, part clown and his films became a reflection of the man. Profound and lurid. Beautiful and sick. Romantic and nihilistic.

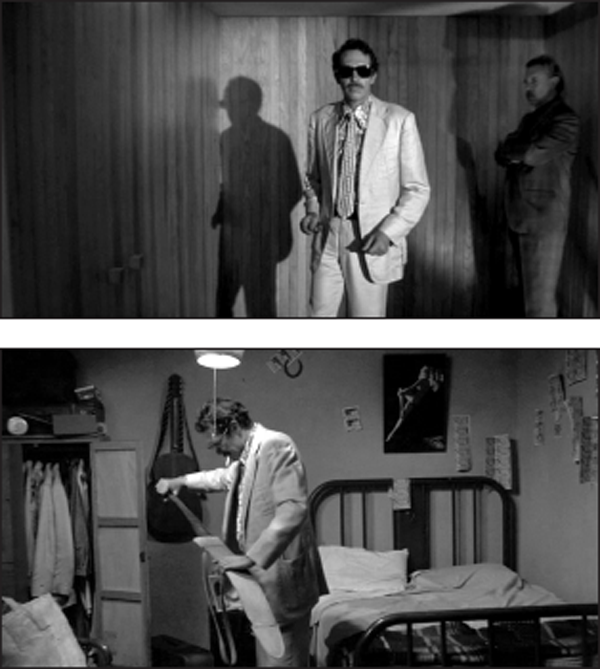

Bennie (Warren Oates) killing his crabs

The opening rural idyll

This idea of division is an important one in Alfredo Garcia. Birth and death, innocence and corruption, wealth and poverty. Consider how the film is awash in alcohol: the tequila Bennie and Elita slug from the bottle as they drive, toasting Alfredo. The beer he swills and spits out before ordering a bottle of brandy. The bourbon Sappensly and Quill buy him at that fateful first meeting. The tequila he uses to kill his crabs and soak Alfredo’s rotting head. The whole movie has a hazy, hung-over quality (is that why Bennie always wears those shades?). In contrast, there are also frequent images of water: the film starts with a freeze-framed pond, leading into a languorous idyll for El Jefe’s daughter as ducks swim by. Later, Elita and the head are both shown in the same shower. In the final scene, El Jefe’s grandson, Alfredo’s son, is baptised. In her Peckinpah obituary, Kathleen Murphy observes how ‘Peckinpah found baptisms where he could, in tacky hotel showers, in the free flow of wine and tequila’ (1984: 74). After Elita’s death, Bennie washes his muddy face from a trough and the green scum coating the surface of the water indicates how far we’ve travelled from the opening shots of sun-splashed water.

DIGNITY AND FAILURE

There is a strong element of autobiography in all this drink and disappointment, the vengeful and the unholy. Peckinpah was from a long line of judges and the law figured prominently in his upbringing: ‘My father believed in the Bible as literature, and in the law’ (quoted in Weddle 1994: 42).

The world of Alfredo Garcia can be regarded as simultaneously exemplifying and reacting against these childhood influences: a godless world which nevertheless is steeped in religious imagery, a lawless world governed not by manmade strictures but elemental drives such as greed, lust, violence and vengeance (Murphy and Jameson consider that ‘the very conceptualisation of the film is violently elemental. One has the sense of an artist loosing his personal demons in the most absolute terms he can devise’ (1981: 45)). As he often does in his work, Peckinpah identifies religion with the corrupt, the ugly and the powerful. The opening images of the film, the repeated dissolves of the water, the heavily-pregnant young woman caressing her stomach and breasts, are contrasted with the interior of El Jefe’s compound, this gloomy, fusty place of patriarchal power and authority, with the oil paintings and the black-clad women, the finery of El Jefe’s clothes and the guards armed with rifles, the blank faces of the priests and nuns who look on impassively as this hideous old man has his daughter stripped and tortured, the gaggle of nuns who kneel before El Jefe’s corpse in the final scene. Consider, too, how Bennie explains to a horrified Elita how he plans to dig up and decapitate her ex-lover:

The church cuts off the feet, fingers, any other goddamn thing from the saints, don’t they? Well, what the hell? Alfredo’s our saint. He’s the saint of our money, and I’m gonna borrow a piece of him.

In the hotel by the cemetery, as they wait for night to fall, Elita asks Bennie if they can visit a church. ‘Yeah’, he answers, ‘later’. They don’t.

This autobiographical aspect is personified in the character of Bennie. He’s a washed-up alcoholic musician working in a brothel in Mexico. Peckinpah was an alcoholic filmmaker who certainly regarded himself as washed-up, given to describing himself as a ‘good whore’, who spent much of his adult life in Mexico. Think of the many mirrors in Peckinpah’s work, many of them shattered by bullets. ‘His filmography is crowded with broken mirrors of himself’ (Murphy 1984: 74). Pauline Kael suggested that the director wanted to make Oates a star but she ‘didn’t think he had it in him to be a star. I think Warren was imitating Sam in the picture because that was his idea of how to be a star’ (in Fine 2005: 269). Kael was often a perceptive critic of Peckinpah and his work but in this instance, she’s plain wrong. Oates steals Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971) and is very good in the same director’s Cockfighter, playing the almost-wordless lead. It is also worth remembering that William Holden offers a career-best performance as a surrogate-Sam in The Wild Bunch, complete with stick-on moustache. Bennie’s clothes and sunglasses, the moustache, the drink and the anger are all suggestive of Peckinpah, as is the character’s progression from sweetness and charm to murderous rage. In creating a hall of mirrors, populated by various alter egos, ‘conscious dopplegängers’ (Kerstein 2006), Peckinpah wasn’t unusual. Directors frequently use stars in such a way: think John Ford and John Wayne or Scorsese and Robert De Niro. Consider the way Hitchcock used Cary Grant as his idealised alter ego (the smooth charmer of To Catch a Thief (1955) or North by Northwest (1959)) while casting James Stewart as a darker variant (the proto-fascist intellectual in Rope (1948) or the romantic, broken necrophile in Vertigo (1958)). Similarly, Kyle MacLachlan is used as a surrogate for the boyish David Lynch of the 1980s (from Dune (1984) to Twin Peaks (1990–91)) but, by 1997, is replaced by the older Bill Pullman in Lost Highway. But still, the degree of identification we see in Alfredo Garcia is uncommon. Gordon Dawson suggests it was never supposed to be taken seriously: ‘It was all camp Sam in a way’, adding, ‘nobody sets out to make that. I can’t believe we made that movie’ (in Fine 2005: 269). Consider, too, the words of Katy Haber, Peckinpah’s long-suffering assistant and on/off lover, interviewed in 2007 for the BBC radio show ‘I Was Sam Peckinpah’s Girl Friday’:

His actors became him. William Holden was Sam in The Wild Bunch, Warren Oates was Sam in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia and Jason Robards was definitely Sam in The Ballad of Cable Hogue.

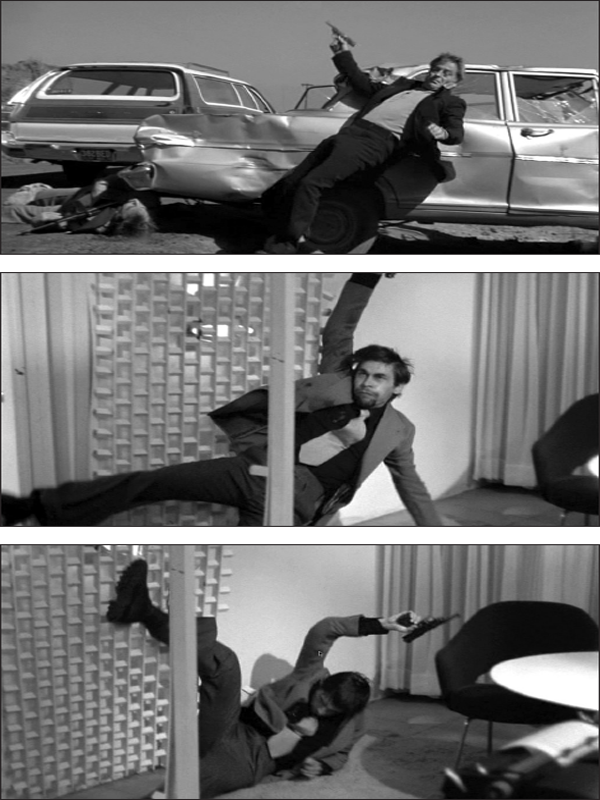

When Elita and Bennie enter the seedy motel near the cemetery (‘a bottle of brandy and a room for the night’), she is taken aback by the squalor, the state of the room, the night manager pissing in a corner of the lobby. Bennie tells her, ‘You oughta be drunk in Fresno, California. This place is a palace.’ Fresno was Peckinpah’s hometown. (There may be another example of this blurring between director and character in Straw Dogs. According to the DVD notes, Dustin Hoffman’s character answers the phone and starts to give his name as David Sam (Peckinpah’s first names), but given that his character is called David Sumner, this is a bit of a stretch. It is a nice idea, though.) If Peckinpah is Bennie, it is hard to avoid the impression that the powerful and sadistic El Jefe is a surrogate for James Aubrey, Head of Production at MGM who had presided over the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid affair. This (very topical in the 1970s) suspicion of ‘The Man’ reflects Peckinpah’s hatred of corporate America: he described politicians as ‘killer apes right out of the caves, all dressed up in suits and talking and walking around with death in their eyes’ (quoted in Seydor 1980: 269). The bounty-hunters, Sappensly and Quill, are far from the stylish hitmen of The Killers (Don Siegel, 1965) or Pulp Fiction, looking more like knackered businessmen in rumpled suits, fresh off the red eye. Like the rest of the interchangeable hoods working for El Jefe, they are loathsome for their bloodless sadism, their anonymity, their lack of humanity. Sure, Bennie is greedy, dirty, even deranged, but he is far removed from these ice-cold ‘well-heeled middlemen’ (Miller 1975: 8). Talking about the ‘suits’ in the hotel room, decadent yet icy, Mark Crispin Miller talks about how they ‘demonstrate neither sexual charm nor desire’ (ibid.). The women who surround them are at best ornaments, at worst irritants (such as the unfortunate whore who grabs Sappensly’s crotch and gets knocked out cold). There is something sickening about these bland, colourless men: witness the revolting scene where a trouserless Max is getting a pedicure from two kneeling women and he swats one of them on the head with a magazine. Or the way they treat Bennie: referring to him scornfully as ‘bartender’, Max leering at him with ‘you want money, don’t you? Money you can spend?’

Max (Helmut Dantine) the killer ape

Presiding over this sleazy, malignant Amerika is ‘Tricky Dicky’ Nixon, who Peckinpah dubbed ‘that cocksucker’ (quoted in Seydor 1980: 269), corrupt and venal. He appears on a magazine cover in the hotel room, perfectly at home amongst whores and killers, these pampered crooks who sneer at Bennie with his clip-on tie. A caricature of the President can be glimpsed on a fake dollar bill pinned to the wall of the bar when we first meet Bennie. And Hollywood is nothing so much as another branch of Nixon’s America, where scruffy drunks with big ideas are at the mercy of soulless breadheads: the director considered it ‘a whole world absolutely teeming with mediocrities, jackals, hangers-on and just plain killers’ (quoted in Seydor 1980: 276).

Peckinpah is often regarded as a victim in his struggles with producers and studios, like Erich von Stroheim, Orson Welles and Nicholas Ray before him, great artists crushed by philistine moneymen. It’s a familiar story, a visionary who is constrained, confounded and ultimately destroyed by the bean-counters: ‘making a picture is … I don’t know … you become in love with it … And when you see it mutilated and cut to pieces, it’s like losing a child or something’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 101).

But the reality may be more complicated than that. One of the first examples of this conflict between art and money was von Stroheim’s Greed (1925). An epic adaptation of the novel by Frank Norris, the film was originally ten hours in length but Irving Thalberg of MGM took it away from the director and had it cut down, first to four hours, then to 140 minutes. Most of the footage considered extraneous was incinerated. It’s a familiar story, all too familiar to Peckinpah, as well as Welles (The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)), Polanski (Dance of the Vampires (1967)), Leone (Once Upon a Time in America (1984)) and countless others. But Irene Mayer, Louis B.’s daughter and the wife of Irving Thalberg, was one of the few who saw von Stroheim’s cut and she tells a different story: ‘It was masterful in ways and parts of it were riveting but it was an exhausting experience; the film in conception was a considerable exercise in self-indulgence’ (quoted in Thomson 2004b: 126). For David Thomson, exhaustion was the aim of von Stroheim’s exercise:

Stroheim’s Greed was not made to please, to reassure, to entertain or to encourage the processes of dreaming and fantasy. Instead it was an attempt to fling odious alternatives in the public’s face. I believe that Stroheim meant to film aggressively and offensively, and for 1925, his way of seeing people was as important as the film’s length … Stroheim gambled mightily with this venture; he must have understood the risk he was running making an impossible, unshowable film. (2004b:124)

Flinging odious alternatives at the viewer, filming aggressively and offensively, an impossible, unshowable film … all charges that could be levelled at Peckinpah and Alfredo Garcia. What needs to be stressed is the fact that as well as being great artists, many of the abovementioned directors were indeed gamblers, tragic heroes with more than their share of fatal flaws. Von Stroheim and Welles were egomaniacs, Ray was a drunken dope-fiend and Peckinpah had a rare talent for self-destruction. It seems a bit redundant to point this out, given his well-documented excesses: four marriages (two to the same woman), his violence, his decades of alcoholism and the debilitating cocaine habit that he developed at the comparatively late age of fifty and continued with, on and off, after the heart attack that led to him having a pacemaker fitted, and up to his death. In an interview the year before Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, the director said ‘sometimes things happen to us because we want them to’ (quoted in Weddle 1994: 483) and, like Bennie, some perverse masochistic side of Peckinpah seems to have driven him to fuck stuff up. Pauline Kael noted:

a tendency among some young film enthusiasts to view him as an icon of artistic integrity. I don’t think they want to understand the role he played in baiting the executives. He needed their hatred to stir up his own. He didn’t want to settle fights or to compromise or even, maybe, to win. He wanted to draw a line and humiliate the executives. He simply wasn’t a reasonable person. He made it impossible for the executives to keep their dignity. (1999)

In the 2004 documentary Sam Peckinpah’s West, Thomson describes Alfredo Garcia as ‘a complete failure commercially’, before adding, ‘I suspect he [Peckinpah] was more drawn to making complete failures than making complete successes.’ Elsewhere, he considered that in Peckinpah’s work ‘little mattered except the self-destructive passion of the men’ (2004a: 13). This penchant for self-destruction reached its inevitable nadir on Convoy, based on the novelty record (!) by C. W. McCall. During the shoot, Peckinpah spent hours holed up in his trailer, snorting coke. Screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer discovered him semi-naked with a live goat and a cocked .38. His drug psychosis got so bad that he telephoned his nephew, David, from the set, claiming that Steve McQueen and the Executive Car Leasing Company were going to kill him. Indeed, as we shall see later in this chapter, some critics have suggested that Alfredo Garcia is nothing so much as a manifestation of this self-destructiveness, a wilful attempt by the director to drive away audiences and trash his legacy.

Admitting Peckinpah’s demented masochism, however, shouldn’t absolve Aubrey. Nicknamed ‘the smiling cobra’ and dismissed by James Coburn as ‘a cocksucker [who] got his kicks destroying films that other people made’ (in Fine 2005: 259–60), Aubrey was brought in to turn around the fortunes of an ailing MGM, crippled by a series of flops and the massive expense of building the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. Pat Garret and Billy the Kid was one of a number of films that fell victim to Aubrey’s cost-cutting and Peckinpah’s resentment and disillusion helped to fuel the black mood of Alfredo Garcia (according to Peckinpah associate John Bryson, the director considered having ‘El Indio’ Fernandez come up from Mexico to have Aubrey killed (see Fine 2005: 257–8)). This makes the end of the film, where Bennie opens fire on El Jefe and his cohorts, a kind of deathwish/suicide fantasy. He (and the director) get to strike back at all of the rich, powerful creeps on their ‘shit list’. Terence Butler considers the whole film to be the director’s attempt ‘to confront the forces that oppress him’ (1979: 9).

Certainly, Peckinpah was not shy about expressing his contempt for the studio suits who, time after time, had stepped in to slash his budgets, re-edit his work and, on The Cincinnati Kid, replace him with Norman Jewison. In 1972, he declared:

This isn’t a game. There’s too much at stake. And the woods are full of killers, all sizes, all colours … You know, you put in your time, you pay your dues and these cats come in and destroy you … There are people all over the place, dozens of them, that I’d like to kill, quite literally kill. (Quoted in Seydor 1980: 275)

David Thomson has argued that Bennie’s quest, this gory deathtrip that ends horribly, can be seen as a metaphor for filmmaking:

For Peckinpah and for Bennie, there is a sort of dignity in the job. If the world is that chaotic and that terrible and that awful, what can you cling to? Well, a job. Maybe that’s why you make films. It’s a job.

Similarly, Roger Ebert says in Sam Peckinpah’s West that the film is ‘a story of a man’s dogged obsession to complete his task in the face of overwhelming anguish’. If one accepts this notion, that Bennie’s mission is akin to Peckinpah’s Sisyphean struggles in the film industry, it is useful to compare the end of the film to the climactic bloodbath in Taxi Driver. Unlike Scorsese, Peckinpah offers no catharsis, little release or pleasure: he even withholds any bravura cinematic technique, offering only a perfunctory, choppily-edited anticlimax. We don’t see Benny die, in marked contrast to The Wild Bunch or Bonnie and Clyde, but there is no coyness masquerading as mythologising either, as in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969) and Thelma and Louise (Ridley Scott, 1991). So effective is this ‘anti-pleasure’ ending that questions often turn up on the IMDb talk boards, viewers feeling that their copy of the film is missing footage. It is no coincidence that Fred C. Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre also dies an ignominious offscreen death to similar, anti-climactic effect. No, Bennie’s victory is a hollow one, so hollow it barely seems like a victory at all.

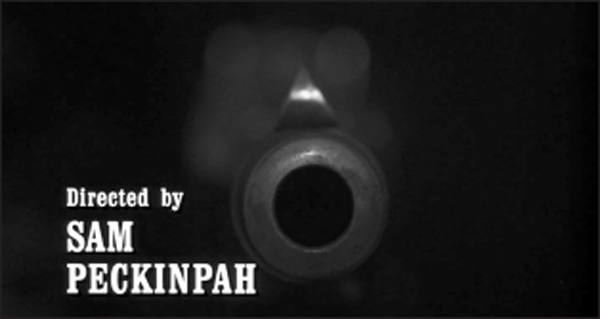

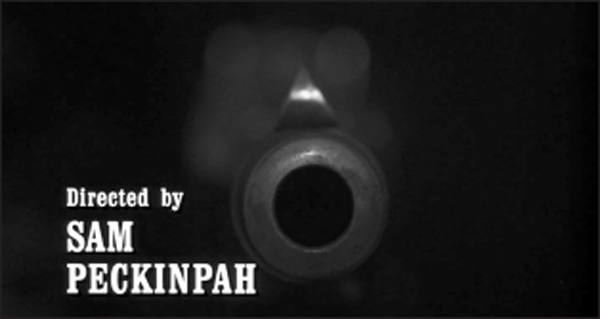

That last shot: Peckinpah’s credit superimposed over the gun that kills Benny. Has anybody used their screen credit with quite the same effect? Think of William Holden’s ‘If they move, kill ‘em’ followed by the director’s name in The Wild Bunch, or the feeding birds and exploding building that accompanies it in The Killer Elite. The ending of Alfredo Garcia is a haunting one, both anti-climactic and cruel. It also plays like a kind of squalid suicide, far from the glorious drawn-out martyrdom bestowed on The Wild Bunch. Kathleen Murphy and Richard Jameson talk of ‘one final hole – in the ground, in a woman, in the end of a gun’ (1981: 48). It’s hard to think of a last shot quite so hopeless. Except it isn’t the last shot. The film does end with Bennie’s death, but freeze-framed images from the film are played out under the credits. We see Bennie and Elita, Sappensly and Quill, the biker-would-be rapist. The penultimate still is an image from the opening scene, the pregnant daughter lying by the water. Just as one starts to suspect that there is a pleasing symmetry to the narrative, the last freeze-frame appears – Sappensly in his black safari suit, looking into the sack at the head within. It’s a strange yet fitting last shot: a badly-dressed hired killer looking at the head, this gruesome McGuffin which we are never allowed a good look at.

Signifying nothing

NARRATIVE: LAZINESS, HAZINESS AND SLOW-MOTION

The film owes much of its unique power to its weird structure, this narrative described by David Weddle as ‘tenuous’ (1994: 495), full of echoes, strange contrivances, the kind of odd repetitions that occur in nightmares or drug trips. Events are doubled up, there are digressions and coincidences, resonances and blurs, reinforced by the washed-out colours and the muddy sound.

As in a dream, the people, objects, landscape and events in ‘Alfredo Garcia’ were constantly transmogrifying, taking wild and improbable leaps in continuity and logic. (Ibid.)

This bizarre narrative approach is easily dismissed as lazy, muddled and slipshod, but it also calls to mind Stanley Kubrick’s desire to ‘explode the narrative structure’ (Krohn 1992) with his Full Metal Jacket (1987), creating ‘not only fragmentation and aimlessness but also a mixture of styles and modes’ (Naremore 2007: 211). The narrative itself seems to be as drunk as Bennie: meandering, talky stretches punctuated by bursts of violence, woozy and staggering. For Steven Prince, Bennie is also the key, being ‘not just the emblem of death but the destroyer of narrative’ (1998: 192). Are we supposed to think that this whole thing is playing out in Bennie’s head?

Plot elements, mise-en-scène and dialogue all combine to create layers of meaning, hazy and half-understood. Our first glimpse of Alfredo is in the locket that contains a photo of his head. Bennie teases Elita about her affair with Alfredo, asking her ‘did he give you good head?’ In reply, she tells him ‘don’t play with my head’. Often the framing cuts the heads off characters. Events double up, repeat, echo. The biker tears Elita’s shirt off, mirroring the opening scenes where El Jefe’s daughter is stripped to the waist. Buses appear on two occasions, one nearly crashing into Bennie and Elita, one turning up as the Garcia family come to collect the head. There are two tyre blow-outs that play a significant role in the narrative. The first leads to Elita and Bennie camping out, the near-rape and the film’s first murders; the second slows up the bounty-hunters, enabling Bennie to catch them up. Bennie accuses Elita of pretending to be sick with a cold when she was cuckolding him with Alfredo; when the bikers arrive, one of them says something about catching a cold from a woman, Kristofferson’s biker blowing his nose when he sits by the fire. Elita and Alfredo are doubled, as she goes from the hotel shower to Alfredo’s grave while the head is unearthed and ends up under the same shower. But the best example of this mirroring occurs with Bennie and Alfredo. The latter was killed driving home from his tryst with Elita and Bennie nearly crashes the car as he kisses her while driving. Quill mentions that Garcia spoke Spanish, English and a little French while Bennie refers to money as ‘pain, bread, dinero’. By the end of the film, Bennie and Alfredo have become one: ‘Just tell them Alfredo Garcia is here’, he tells the guards at El Jefe’s place. As if to emphasise the negativity on show here, the film is book-ended by echoed cries of ‘No!’. El Jefe’s wife cries out as her daughter is tortured, Bennie screams it repeatedly as he kills the bodyguards in the compound and says it again quietly, before shaking his head and shooting El Jefe. When Sappensly asks Bennie if he knows Alfredo, there is the sound of a car crash and it is unclear whether it is a diegetic sound from the street outside or just in Bennie’s head, a premonition or a way of doubling both men in death (Bennie, too, will die in his car). These contrivances and echoes help to create a narrative which is both ‘self-conscious and bleakly playful’ (Prince 1998: 208). There is also, possibly, another allusion to Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in the way that Bennie seems to be at the mercy of malign forces, forces described by the grizzled Howard as ‘a great joke played on us by the Lord or fate or nature’. Note how in both films, bad fortune comes to the protagonists disguised as luck. In Huston’s film, penniless losers Dobbs and Curtin (Tim Holt) happen to walk into the flophouse just in time to hear Howard’s stories about prospecting gold. Later, as the men pool their cash only to discover they are 600 bucks short, up pops the street kid who pestered Dobbs into buying a lottery ticket, telling him he’s won 200 pesos. Without these strokes of what seems like luck, their ill-fated trip would not have happened, the gold would still be in the mountain and Dobbs would be alive. In much the same way, a series of chance meetings (Sappensly and Quill’s initial questioning of Bennie, their later appearance as the Garcia family take back the head) and accidents (the burst tyre, the arrival of the bus that enables Bennie to get his gun) that seem to be fortuitous only end up leading Elita and Bennie to the grave.

The dialogue seems emblematic of this ‘strange complexity’, often hard-boiled and pulpy to the point of being camp, yet delivered by the cast as if they really mean it: take Quill’s ‘if your information is wrong, you too are wrong. Dead wrong.’ Or how about El Jefe’s plaintive ‘he was like a son to me’? Bennie gets all the best lines, however: snarling at the bikers, ‘you guys are definitely on my shit list’; to Elita, after shooting his gun at a flock of birds, ‘Hell, I wasn’t trying to hit ‘em, you know?’; ordering a drink with ‘a double bourbon with a champagne back, none of your tijano bullshit, and fuck off’; his heart-rending ‘I love you’ as he sits under the shower with Elita; addressing onlookers with the surreal ‘don’t look at me with your goddamn fuckin’ eyes’. The last quote is an important one, I think. This is a film about looking. Consider Bennie’s shades, worn in bed but not on a bright sunny day, the way he flinches when he’s photographed with them off or the fact that he can barely look at his reflection without them. And there are the mirrors we see in at least five scenes. But it is also a film about what we don’t see, this being, paradoxically, both Peckinpah’s most violent film and one of his most restrained. We don’t get a good look at the severed head, we don’t see Alfredo’s corpse or Elita or Bennie die. The best illustration of this paradox is the scene where Bennie shoots one of the wounded bounty-hunters lying on the ground. The shot flips the man over onto his back and Bennie asks himself ‘Why? Because it feels so damned good’, before shooting him again. This scene, described by Steven Prince as ‘perverse and horrible, but lyrically so’ (1998: 195) would seem, given the director’s ‘Bloody Sam’ image, to be overkill to the point of self-parody: Murphy and Jameson suggest as much, saying of the shooting and its aftermath, with Bennie throwing the head into the car (and at the camera), ‘it’s as though the director were saying “This is what you think I am: this is what you came for. Well, here it is!”’ (1981: 48). But the self-conscious framing of the shot means our view of the man lying on the floor is hidden by an open car door and the last shot (fired into his head?) goes unseen. The final frame of the film, Sappensly gazing at a sight we never see, the head in a sack, is another illustration of this weirdly discreet horror. The framing of shots throughout the film is often strange, suggesting contrived artlessness or carelessness, it’s hard to say which. It could be both. Some scenes are characterised by the kind of seeming impatience with form that occurs often in many Fassbinder films or Woody Allen’s work from the early 1990s (Husbands and Wives (1992), Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993)), while the choppy editing often feels like a lesser director ripping off the Peckinpah style: indeed, the weird cutting of the shoot-out in El Jefe’s compound resembles nothing so much as Michael Winner’s films (such as the painful Dirty Weekend (1993)). It is certainly very far from the accomplished use of form displayed in the director’s previous films and although he would go on to make some bad films, there would be nothing quite so strikingly odd. Even incidental scenes are framed in such a bizarre fashion as to be disorientating: when Bennie enters the Hotel Camino Real, we see him reflected in a wall-mounted mirror as he approaches the desk. The mise-en-scène is often excessive, the frame cluttered with garish décor, crowded with people. Often this approach is used to great effect, creating a sense of disorder and mess: look how cramped Bennie’s room feels, the stuff on the walls, Elita’s guitar, her rolling out of bed and tumbling to the floor. Or when Bennie stands there in the half-light, a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, unsheathing the machete: behind him the frame is full with the bed, the open wardrobe, the postcards and photos, the lamp with the dangling cord. Or the scene in the bar where Bennie works, the master shots stuffed with bodies, Bennie, Sappensly and Quill, the whores and the punters. This clutter that seems to make up Bennie’s world is contrasted with the airy anonymity of the hotel rooms where El Jefe’s hoods hang out, the space, the wooden doors set in this great wooden wall, the pastel colours. If, as the Italian horror auteur Dario Argento has suggested, ‘buildings are like your inside … buildings are souls’ (quoted in Reesman 2008: 71–2) we can regard Bennie as a mess and the sleazy hotel-dwellers as a bunch of anonymous blanks.

A weirdly discreet horror

The cluttered frame

Buildings are like souls

Particularly noteworthy is the cavalier use of slow-motion, the formal device most associated with the director: as the veteran Howard Hawks wryly noted, ‘I can kill ten guys in the time it takes him to kill one’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 151). Peckinpah wasn’t the first director to utilise slow-motion in his action scenes: Henri-Georges Clouzot in Le salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear,1953), Akira Kurosawa in Shichinin no samurai (The Seven Samurai, 1954) and Arthur Penn in The Left-Handed Gun (1958) and, most notably, Bonnie and Clyde. But the fact that Peckinpah became synonymous with slow-motion action scenes is a testament to how he mastered the technique. As well as the aforementioned Monty Python sketch ‘Sam Peckinpah’s Salad Days’ (see introduction), the director’s use of slow-motion was also parodied in a sketch from The Benny Hill Show. Add to that John Belushi’s Peckinpah skit from an episode of Saturday Night Live where his working method involves brutalising an actress, and it is clear just how much of a ‘cult of personality’ surrounded ‘Bloody Sam’ and just how strongly he was identified with stylistically excessive violence. Who out of today’s crop of directors could be so accurately skewered in popular entertainment shows?2

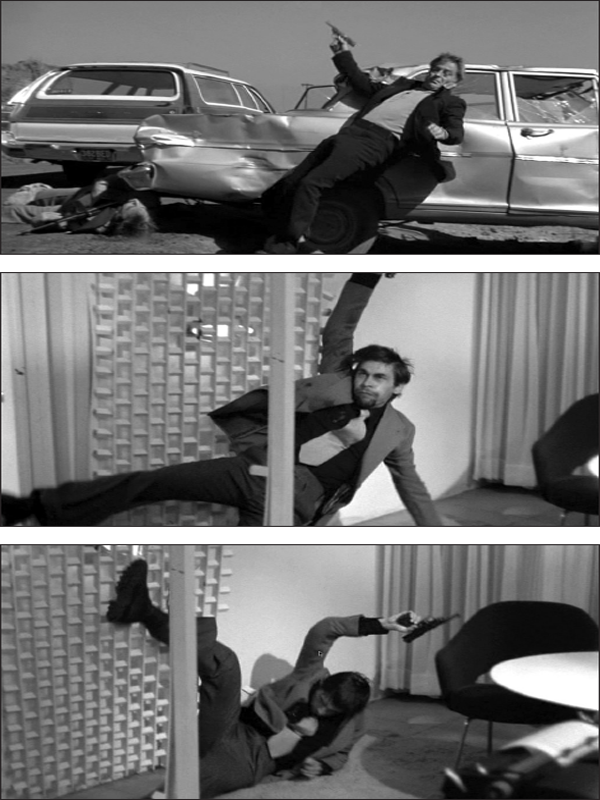

Peckinpah set out to avoid the use of whole slow-motion scenes and instead would interweave footage filmed by six cameras filming at various speeds, creating an effect that was simultaneously exhilarating, sickening and disorientating. According to the director, his desire to use slow-motion arose from witnessing an act of violence whilst on military service in China. However, he couldn’t get his story straight, telling one interviewer how he was on a train when ‘a bullet tore through a window and into a nearby Chinese passenger, killing him immediately … I noticed that time slowed down’ (quoted in Weddle 1994: 55). Yet elsewhere, he claimed he was the victim: ‘I was shot and I remember falling down and it was so long’ (quoted in Fine 2005: 24). Wherever his inspiration came from, after a faltering start with the botched Major Dundee, he mastered the technique, with The Wild Bunch shocking and thrilling audiences in equal measure with violence both graphic and graceful. As David Weddle puts it, ‘the action would constantly be shifting from slow to fast to slower still to fast again, giving time within the sequences a strange elastic quality’ (1994: 334). In Straw Dogs, he modified his style further, integrating slow-motion flash inserts into scenes. But in Alfredo Garcia, the technique seems to be applied in an almost random fashion, such as the slowed-down scene of a bus careering though mud (!). There are repeated shots of bodies falling to the ground, limbs askew and hair flopping, emphasising the ugly mechanics of death. Here, the slow-motion footage smacks of a kind of authorial self-loathing, a cavalier, even pedestrian use of his stylistic trademark. There are some striking moments, however, when Peckinpah uses it as effectively as he ever did, such as the shot when Bennie, lying in the grave, lets go of Elita and she slips out of his embrace and back into the soil.

Slow-motion and the messy business of death

GENRE

Generically, Alfredo Garcia is, on the surface, a kind of love story-cum-horror film. But there are more genres and cycles thrown into the mix, including the then-voguish road movie, the western and the buddy movie. The road has traditionally represented opportunity and escape in American culture, the notion of the quest an important one that taps into the pioneer spirit. In literature (The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) by Mark Twain, As I Lay Dying (1930) by William Faulkner, The Grapes of Wrath (1939) by John Steinbeck) and film (It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), You Only Live Once (Fritz Lang, 1937), The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939)), the idea of Americans as a rootless people engaged in the search for a place to call home is a recurring one (and one that continues beyond the stars in Spielberg’s E. T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)). There was a dark side of the road, however, which is best portrayed in Detour (1945), Edgar Ulmer’s nightmare uber-noir shot in five days. The 1960s and the notion of ‘dropping out’ saw the road movie re-emerge, a perfect vehicle (pardon the pun) for the ‘passive hero’ imported from the European art movie, a stoned rebel without a cause. Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969), Two-Lane Blacktop, Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970), Vanishing Point (Richard C. Sarafian, 1971) and a host of lesser films saw the road as offering an alternative to ‘straight society’, albeit one that often ended unhappily: Easy Rider, Vanishing Point and Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry (John Hough, 1974) all end in death while the rootless protagonist of Five Easy Pieces just keeps moving on. The most striking finale is that offered in Two-Lane Blacktop where, stealing an idea from Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), the car literally burns up the screen. In Alfredo Garcia, when we first meet Bennie, he is a passive drifter, declaring that ‘I’ve been no place I want to go back to, that’s for damn sure’. This may be yet another echo of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, where another misplaced gringo, Curtin, says bitterly ‘all places are the same to me’. But Peckinpah’s view of the road is the bleakest since Ulmer’s: Bennie may as well be driving round and round in circles, knocking back tequila from the bottle. As he comes undone, so too does his car, the gleaming red convertible he sets off in becoming a grimy wreck, the bodywork battered and the windscreen caked in dust. The endless possibilities offered by the open road come down to this: Bennie, muddied and bloodied, waving the flies away and opening the window to rid himself of the stink of rotting flesh. As one reviewer commented ‘Everything in the world that this movie depicts is inescapably tainted, grubby, and dirty’ (Jon 2007; emphasis in original). Alfredo Garcia seems to have marked a turning point for the sub-genre: the year after Peckinpah’s film, Oates took another ill-fated road trip (with Peter ‘Captain America’ Fonda) in Race with the Devil (Jack Starrett, 1975), only to be hunted by backwoods satanists, and these illstarred journeys became the template for later road movies such as Something Wild (Jonathan Demme, 1986), Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994) and The Doom Generation (Gregg Araki, 1995). In their introduction to The Road Movie Book, Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark identify a group of films within the road movie sub-genre, concerned with outlaw couples. Although not a new phenomenon (with examples going back as far as the above-mentioned Fritz Lang film and Nicholas Ray’s debut They Live By Night (1948)) Cohan and Hark argue that this is a cycle that really came into its own in the 1970s, with ‘the deferral of sexual intimacy’ seen in classical Hollywood films no longer plausible for audiences and consequently ‘heterosexual road movies had to derive their frisson instead from implicating the couple’s sexual union in a wider tapestry of violence which became just another version of their relationship’ (1997: 9). Peckinpah’s film fits this template, with its mix of heartfelt romance and brutal violence, a mixture that would be pushed to absurd extremes in the Southern Gothic of David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990).

The opening minutes of the film suggest a western. The men who come to collect El Jefe’s daughter are wearing sombreros and jangling spurs, there’s a rider on horseback and abundant cacti. There is nothing in El Jefe’s mansion to indicate it is the 1970s. So it comes as jarring to the viewer when we see aeroplanes and screeching cars (Peckinpah used a camel to similar disorientating effect in the opening of Ride the High Country). The western is also the American genre most strongly associated with Mexico. Although it has had a home-grown film industry since the early twentieth century, the country has been ill-served by Hollywood, portrayed as a lawless place of sleaze and death (the kind of place evoked in the song ‘Hey Joe’, where the eponymous character shoots ‘his woman down’, before ‘heading down to Mexico way, where a man can be free’). Outside of the western and the travelogue images of froth like the Elvis Presley picture Fun in Acapulco (Richard Thorpe, 1963) and The Real Cancun (Rick de Oliviera, 2003), Hollywood’s Mexico takes in the seedy motels and knife-wielding hoods of Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958), the brothels and rapes of Revenge (Tony Scott, 1990), the sickly yellows of the drug drama Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000), the corruption and kidnapping of Man on Fire (Tony Scott, 2004) and the cruising cowboys of Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005). Like Peckinpah, John Huston lived on and off in Mexico and offered some heated, lurid visions of life south of the border: the aforementioned The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Richard Burton’s drunken defrocked priest in Night of the Iguana (1964), Albert Finney’s smashed writer in Under the Volcano (1984), a film Peckinpah had lobbied to make. For both directors, the country offered a kind of refuge from a puritanical America. David Weddle calls Peckinpah’s Mexico ‘an Old Testament realm offering polarised visions of Eden and Sodom’ (1994: 37). To Kathleen Murphy and Richard Jameson, it offers ‘a womb-tomb where sex and death, fecundity and decomposition are not discrete but simultaneous processes’ (1981: 45). According to John Kraniauskas, the film ‘creates an ambiguous and mythic space out of Mexican materials, a border zone between the Mexico it so strongly refers to and the West it is not’ (1993: 33). But Richard Combs, one of the few reviewers to admire the film on its initial release, points out the ‘Conradian horror that overtakes Peckinpah whenever he steps outside America’ (1985: 397). If one rules out Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (all set largely in Mexico but also containing sequences set north of the border), the director’s three films set outside the US, Cross of Iron, Straw Dogs and Alfredo Garcia, are his most savage (and while a film set on the Russian front in 1943 is bound to contain many violent scenes, Straw Dogs plays out its rape and bloodshed against the backdrop of a sleepy Cornish village). Peckinpah said of the country, ‘Mexico has always meant something special to me. My Mexican experience is never over’ (quoted in Thomson 2009: 34).

Of course, as a western, Peckinpah’s film is far from the classic genre films of Hawks and Ford: ‘in fact this revisionist western is so revisionist that it has jets, convertibles, accountants and modern Mexico City in it’ (Moody 2009). Although Philip French detects elements of Ford’s The Searchers (1956) in Alfredo Garcia, describing it as a ’Peckinpah favourite’ (2009), the director had dismissed it as ‘one of [Ford’s] worst films’ (in Macklin 2008: 154). But the genre had undergone considerable changes in the 1960s and 1970s, with the graphic, stylised violence of the Italian westerns and the addition of counterculture values and a great deal of moral ambiguity. Examples of such revisionist fare include the aforementioned work of Arthur Penn, the bitter Vietnam allegory Ulzana’s Raid (Robert Aldrich, 1972), Altman’s typically genre-bending McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) and the wild west ghost story High Plains Drifter (Clint Eastwood, 1973). The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (John Huston, 1973) was an episodic comedy western with Ava Gardner’s Lillie Langtry, Stacy Keach’s albino gunman and a pet bear while Dirty Little Billy (Stan Dragoti, 1972) starred Michael J. Pollard as a gargoylesque Billy the Kid (with the provocative tag-line ‘Billy the Kid was a punk’). There were also the more self-consciously outré arty westerns such as Andy Warhol’s playful Lonesome Cowboys (1968), the trippy bloodbath El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970) and the anarchic The Last Movie. Discussing Peckinpah’s earlier work, Paul Schrader suggested, in Sam Peckinpah’s West, that his ‘contribution to the genre was like Orson Welles’s contribution to the film noir … which is that he chiselled the gravestone’; but if the truth be told, the graveyard was pretty crowded with filmmakers wanting to bury this most traditional of American genres. Peckinpah may have been the most accomplished of them, but what Alex Cox calls the western’s ‘revolutionary tendency … postmodern, respecting neither genre nor linear narrative: the cowboy version of punk’ (2006), would continue at least until the stunning Heaven’s Gate.

With its bleakness and gore, creepy country graveyard and decapitation, Alfredo Garcia often resembles a gothic horror. It is possible to read the whole thing as a weird variant on the zombie film. Comparing Peckinpah to Howard Hawks, Kathleen Murphy says, ‘in their darkest films, it’s as though everyone is dead already’ (1984: 74). To Steven Prince, Bennie is ‘the walking dead’ (1998: 192). It is significant that as Bennie literally rises from the grave after the seconds of black screen that follow the spade blow to his head, we get a brief point-of-view shot of his hand clawing at the soil. This raises the possibility that from that point on, we are watching the vengeful dream of a dead man. Consider, too, the use of ‘Bennie’s Song’, sung by Elita as they drive to the cemetery. According to John Kraniauskas, the song is a Mexican popular ballad called a corrido that ‘tells us that Bennie will die … because traditionally corridos are sung to remember the dead’ (1993: 33). For Phil Nugent, ‘it’s when Bennie emerges from the grave that Alfredo Garcia kicks into high gear’ (2005). The action scenes are more stylish, the scenery – ‘as if replenished by fresh blood’ – is more beautiful and Oates comes into his own:

As a would-be movie star he’s an unobtrusive presence in search of a part but as a walking dead man he’s scarily potent and convincingly dangerous. (Ibid.)

Bennie is a walking corpse, whose desire for revenge forces him to leave his love sharing a grave with the man who cuckolded him. This nightmare quality is reminiscent of other films that play out like death dreams: Vertigo where James Stewart’s Scotty is left hanging from a roof at the start of the film with no way down or Point Blank (John Boorman, 1968), where we are never really sure if Lee Marvin’s Walker is dead from the start, the events of the film just the revenge fantasy of a dying man. But a palpable sense of the gothic and the nightmarish was always there in Peckinpah’s work. He worked as a writer on the paranoid classic Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (Don Siegel, 1956), and his first film, The Deadly Companions, transplanted William Faulkner to the wild west, with a decomposing corpse transported cross-country. The rural nastiness of Straw Dogs is evoked in horror films such as The Wicker Man, An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1980) and Eden Lake (James Watkins, 2008).

Alfredo Garcia also seems to be influenced by the buddy movie. This was a cycle of films about male duos that flourished in the New Hollywood. Whether the subjects were stoned long-hairs (as in Easy Rider and Two-Lane Blacktop) or cops (as in Hickey and Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972), Freebie and the Bean (Richard Rush, 1974) or Busting (Peter Hyams, 1974)), cowboys (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) or hipster medics (MASH (Robert Altman, 1968)), buddy movies celebrated male friendship and, for the most part, excluded female characters. As Bennie and Alfredo drink, drive and shack up in motels together, Peckinpah appears to be offering up a grim satire of the cycle. Note the way that, in time-honoured fashion, their initial antagonism changes to something like understanding, as Bennie tells the head, ‘Hell, it wasn’t your fault. I know that. But we’re going to find out. You and me.’ This strange duo, the demented loser and the decomposing head, the oddest couple of all. Perhaps inevitably with all this testosterone, there was a strong streak of homoeroticism running through the buddy movie and in an attempt to counter this (and ‘reassure’ viewers as to the protagonists’ ‘uncomplicated’ maleness), a series of lame gay stereotypes recur throughout this cycle. After all, how can anyone see anything sexual in Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro sharing a bed in Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese, 1973) after we’ve been presented with Ken Sinclair’s Sammy (‘hey fellas, you going my way?’), camping it up in his yellow mac and white flares? After Harry Dean Stanton’s appearance as a hitchhiker who hits on Warren Oates (‘I just thought it might help you relax while you drive’) in Two Lane Blacktop, who could suspect anything more than camaraderie between moody Dennis Wilson and the even-moodier James Taylor? Even gay directors can be guilty of this, with John Schlesinger attempting to offset the romance between Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy (1968) with squirming, nerdy Bob Balaban. Robin Wood has described this device as ‘a disclaimer’ (1986: 229), although sometimes, a buddy movie will foregound this homoeroticism: in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (Michael Cimino, 1974), Clint Eastwood bonds with a fetchingly dragged-up Jeff Bridges. With the characters of Sappensly and Quill, this woman-bashing gay partnership, Peckinpah may well be mocking this bizarre tendency. Whereas the buddy movie was perceived by some to be a response to feminism and the perceived threat it posed to all things masculine, Wood takes a more positive view, seeing the cycle as offering a kind of liberation: ‘If women can be dispensed with so easily, a great deal else goes with them … marriage, family, home’ (1986: 227). In this light, we can see just how hopeless a vision Peckinpah offers, subverting both the road movie and the buddy movie, substituting violence and pain for the joys of the open road and homosocial camaraderie.3

For some, the ‘masculinist’ tendencies at play in the buddy movie are also evident in the cult film audience. For Mark Jancovich et al.:

The aesthetics of transgression that underpins so much cult movie fandom is often directly opposed to the values of domesticity that are not only associated with femininity but for which women have historically been presumed to [have] been responsible. (2003: 3)

Significantly, all of the genres/cycles that can be discerned in the mishmash of Peckinpah’s film flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in part due to the perceived anti-establishment credentials of films from the period as varied as Night of The Living Dead, Five Easy Pieces, Little Big Man and MASH. Weirdly, Peckinpah was embraced by the counterculture of the period. This was, in no small part, due to his casting of musicians such as Kristofferson and Bob Dylan (who scored and appeared in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid). But there was also his carefully-contrived outlaw persona, the beard and bandana, the drink and drugs. In interviews, he spoke out against Nixon and the war in Vietnam. The controversy surrounding The Wild Bunch also played a part, particularly the suggestion that its opening scenes (with vicious Americans in uniform slaughtering civilians) referenced the war.

There is an admitted irony in the fact that ‘The Love Generation’ flocked to see such violent cinematic fare, from Bonnie and Clyde to A Clockwork Orange, particularly when a number of these films seem to consciously bait their hippy audiences: consider Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) in The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and his credo of ‘never trust a nigger … never trust anyone’, or the rapist/ murderer of Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) with his long hair and peace-sign belt-buckle. But all the anger and acid of the late 1960s meant that psychosis was never faraway, both onscreen and off: the Weathermen, the Manson Murders and the way über-hippy Dennis Hopper morphed into the villainous perverts of Out of the Blue (Dennis Hopper, 1983) and Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986). This sense of disillusion, the harsh comedown after the heady trip of the ‘Summer of Love’, feeds into many 1970s films and Alfredo Garcia is no exception. (In truth, Peckinpah was, in the vernacular of the time, a bit of a square. He didn’t know who Dylan was when the singer expressed an interest in working with him and when they did meet, the director tried to impress Dylan by telling him he was a big Roger Miller fan.) Although he was no hippy, he was deeply affected by the war in Vietnam and this fed his loathing for Nixon. As an ex-serviceman, he was particularly outraged and saddened by the slaughter of civilians in the village of My Lai in 1969, even going so far as to write a letter to Lieutenant William Calley, the man convicted over his role in the massacre. Vietnam, like the Nixon presidency, seems to bleed into many of Peckinpah’s films, in much the same way that the Holocaust bleeds into the noirs of the 1940s or the atrocities in Iraq, from Internet beheadings to the torture photos from Abu Ghraib prison, have made their mark on contemporary horror films like Saw (James Wan, 2004), Wolf Creek (Greg McLean, 2006) and Hostel (Eli Roth, 2006). Peckinpah seems to have been aware of the topicality of the film. In a letter to the Swedish Censorship Board, responding to their decision to ban Alfredo Garcia, he acknowledged that ‘some people may find my films difficult and even terrifying but they cannot ignore the world today’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 228). In interviews, Peckinpah offered a pessimistic, despairing view of 1970s America: ‘You know what this country’s all about, doctor? It’s brainwashing, it’s bullshit. It’s hustling products and people, making no distinctions between the two. We’re in the Dark Ages again’ (in Murray 2008: 118). His cure for this bleak situation? ‘We have to water the flowers – and screw a lot’ (2008: 119). Like a great many social critics, Peckinpah is better on diagnosing the problem than offering a solution: it isn’t for nothing that he told interviewer Barbara Walters ‘that it was not in his power to present constructive values in his work’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 145).

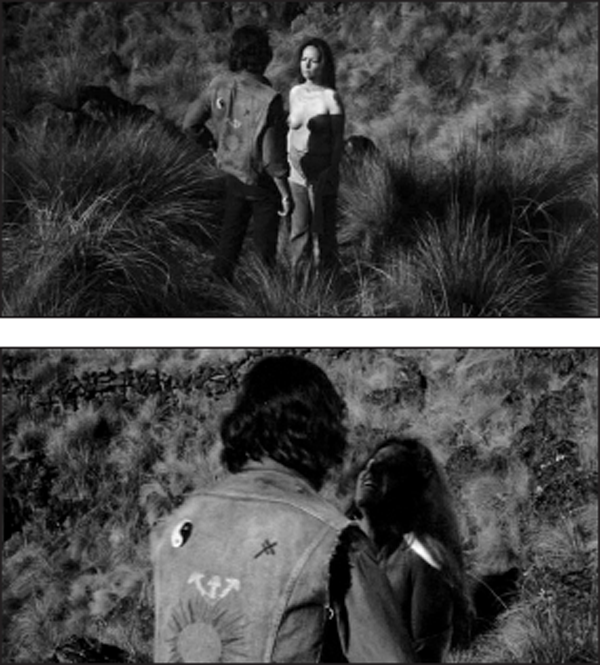

WOMEN

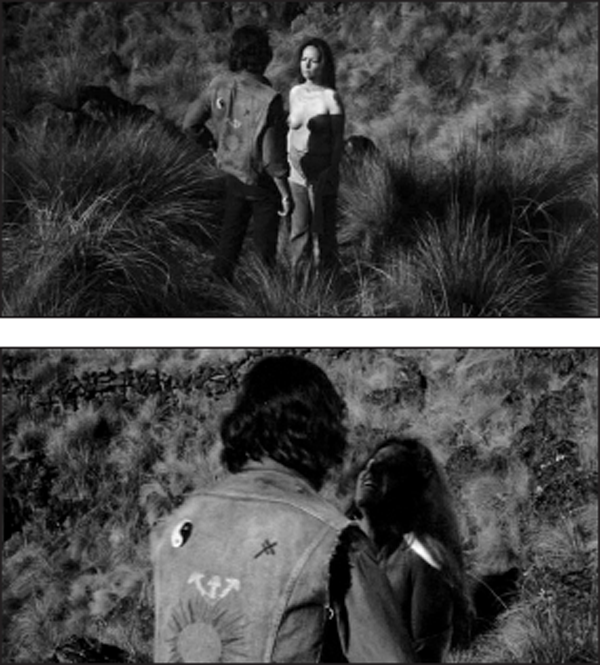

Then there is the question of women. With the possible exception of slow-motion violence, nothing says Peckinpah like misogyny, accusations of it swarming round his work like the flies around Alfredo’s head. The chief area of debate concerns the director’s depiction of sexual violence, where the line separating seduction from coerced sex/rape is frequently blurred, if not dissolved completely. The most notorious example of this is Straw Dogs, where Peckinpah’s avowed intention to ‘shoot the best rape scene that’s ever been shot’ (Thomson 2002a) led to the film being unavailable for home viewing in the UK from 1984 to 2002. There are thematically similar incidents in The Getaway and Cross of Iron (indeed, one might argue that any filmmaker who stages even one rape/seduction is skating on pretty thin ice). Unlike some critics, I do not intend to tie myself in knots defending Peckinpah on this score: his attitude to his female characters is frequently unpleasant and often troubling. Gabrielle Murray is almost euphemistic when she talks of his ‘sometimes abberant treatment of the representation of women’ (2002). It is, however, undeniable that some of the most perceptive commentators on his oeuvre tend to be female, including Murray, Pauline Kael and Kathleen Murphy. The character of Elita is one of the more complex of Peckinpah’s women but this might not be saying much. She is frequently undressed (and was the subject of a Playboy spread shot on the set) but given Peckinpah’s oft-quoted claim to be ‘like a whore … I go where I’m kicked’ (in Bryson 2008: 143), it is possible to see her as another of the director’s surrogates. Indeed, for Mark Crispin Miller, all of the characters are selling themselves: he dubs Bennie ‘a whore lost in a world of whores’ (1975: 9). The director suggested that the women in Alfredo Garcia are the ‘positive poles … the lifeforce and instinct’ (quoted in Prince 1998: 149), and if this is the case, it speaks volumes about the world of the film that they are stripped, abducted, abused and killed. Steven Prince relates the experience of Garner Simmons, author of Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage (1982) and a friend of the director, who was there for the Alfredo Garcia shoot, and who recalled how, as Peckinpah filmed El Jefe’s hoods breaking his daughter’s arm, the director’s ‘eyes filled with tears’ (1998: 160). Prince regards this ‘grieving response’ as ‘an indice of humane perspective’ (ibid.) but I am not so sure. Peckinpah reportedly cried easily, bursting into tears at Dylan’s songs for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and while filming the climactic battle in Cross of Iron. It is also worth remembering D. H. Lawrence’s dictum, often quoted by Robin Wood, that one should ‘never trust the artist – trust the tale’ (Wood 1999: 171), and by that measure, Peckinpah’s treatment of his women (onscreen and off) is disturbing. The scene where the two bikers (played by Donnie Fritts and a hirsute Kris Kristofferson) happen upon Bennie and Elita is creepily opaque. While one of the men holds Bennie at gunpoint, Elita tries to reassure him as the other man drags her away, saying, ‘I’ve been here before and you don’t know the way.’ Out of sight of the others, her abductor uses his flick knife to slit her shirt before tearing it off, the framing of the shot revealing the yin and yang patch and the cross on his denim jacket. The score here is intrusive, creepy and discordant (the film’s soundtrack album labels this piece ‘Prelude to a Rape’). Elita slaps the biker twice before he slaps her back, only to reach out to caress her gently. Then he stops and walks away, lost in some sort of existential biker fug, sitting down and picking at a blade of grass. Back at the campfire, we can sense a weird kind of camaraderie between Bennie and his captor. When Bennie snarls, ‘What the hell, she can handle it a lot better than I can’, the biker replies, ‘she sure can’. Even under these circumstances, men bond with each other more easily than they do with the women they love. The biker plays Elita’s guitar as he sings to the increasingly pissed-off Bennie, who sits glowering by the light of the fire. The song he sings, ‘Bad Blood Baby’, was written by Peckinpah and the salacious lyrics seem to be mocking Bennie and his predicament:

‘I’ve been here before and you don’t know the way’

Ain’t it driving you insane?/Well, he’s eaten up all your candy/ain’t it turning [sic] up your brain?/She’s got bad blood baby/ … Well he’s got her on her back now, showing him just what she’s got’.

Elita’s mood appears to change and, still topless, she follows the biker and kneels before him. There is a blank expression on Vega’s face which manages to be simultaneously erotic and eerie as she whispers, ‘Please don’t’, then after a meaningful pause, ‘please’. They kiss passionately and it is clear that she is a willing participant. They move until she is, in the words of the song, ‘lying on her back now’ with the biker above her, and it is this sight that greets Bennie when he arrives, gun in hand. Peckinpah was fascinated by questions of loyalty and betrayal: it is a recurring theme in his work and this sequence is a good example of this. Indeed, it was one of the first scenes the writers came up with. As mentioned earlier, Frank Kowalski was interested in writing about Caryl Chessman, the ‘Red Light Bandit’. Unlike the many artists (including Ray Bradbury, Lenny Bruce and Aldous Huxley) who regarded Chessman as the victim of a miscarriage of justice, Kowalski was more interested in his crimes: ‘He used to rape girls and then take off. That idea intrigued me and Sam: what if someone was raping your girl and you had to stand and watch?’ (in Fine 2005: 267). This scenario, with its associations of impotence and rage, violence and betrayal, seems to be one Peckinpah tormented himself with and it recurs in his work: he doesn’t identify with the raped Amy (Susan George) in Straw Dogs but rather with her unsuspecting husband, David (Dustin Hoffman), lured away on a phony duck hunt. He doesn’t side with the abducted, raped Sally Struthers in The Getaway but rather with her humiliated husband, who is tied to a chair and forced to watch as she cavorts (willingly? Semi-willingly?) with her abductor. The Kristofferson character goes from a leering, grinning creep with a gun at the campfire to a soulful, almost dreamy charmer once he is alone with Elita and she responds in a way that illustrates Bennie’s (and, seemingly, the director’s) worst fears. His female characters are slapped, shot, raped, drugged and strangled: David Thomson’s (slightly breathless?) observation that ‘in Peckinpah films, women must expect to get stripped to their white brave breasts. It comes with the territory, like being smashed in the face’ (2009: 35) actually seems to downplay the worst of these excesses (the aforementioned Amy or the naked woman (Merete Van Kamp) in the opening minutes of The Osterman Weekend, whose post-coital masturbating is interrupted by assassins who kill her with an injection to the face). Still, Peckinpah seems to rarely, if ever, empathise with these suffering women, just with the men who love them. Not with Elita, led off, stripped and slapped but with Bennie, sat by the campfire, making threats and drinking tequila.

She, like many Peckinpah women, is ‘collateral damage’ (Kerstein 2006) in this struggle between men. The fact that she reacts so passionately to her would-be rapist rubs further salt into Bennie’s wounds: we don’t know why she kisses the biker but we do know how Bennie feels when he sees her doing it. It’s about the men, the losers, the suckers, the cuckolded and the humiliated. This ambiguity and cruelty we sense in Peckinpah’s depictions of women are important, adding a dark dimension which can make the viewer uncomfortable (indeed, the unsimulated cruelty to animals in some of the director’s films – the decapitated chickens, exploding lizards, tripped horses and burning arachnids – seems to perform a similar function). A big part of this discomfort is the lack of a clear context for all this sexual violence, the authorial point of view often unclear. In Martin Barker’s characteristically thoughtful piece on audience reactions to Straw Dogs, ‘Loving and Hating Straw Dogs: The Meanings of Audience Responses to a Controversial Film’ (2006), he refers to an article written by Charles Barr for Screen in 1972. Barr examined the tendency among many critics to defend Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange while condemning Peckinpah (for example, the 13 British critics who wrote to the Times, describing Straw Dogs as ‘dubious in its intention, excessive in its effect’ (Barr 1972: 17)). As Barker puts it:

Barr makes a still-compelling case that those who hated Peckinpah’s film so much were expressing a fear of ‘contamination’ – because the film did not permit distancing from the ambiguities of feeling which the actions and events of the film portrayed. (2006)

This fear of ‘contamination’ may explain a lot of the revulsion towards Peckinpah’s treatment of sexual violence, which is so often ‘a strange mix of the explicit and the oblique’ (Kermode 2003).

Is Elita offering herself up to protect Bennie? Is she turned on by the situation? Does it matter? It is part of the power of Peckinpah’s work, this ability to unnerve and provoke, to scratch at something until it starts to bleed. Writer/director Paul Schrader has talked of how Peckinpah’s work inspired him ‘to go into your neuroses, to go into those things about yourself that you fear, not to cover them up but to open them up’ (in Weddle 1994: 12). It is also, surely, a bit of a dead-end to judge films largely on their espousal of ‘progressive’ values. One may get a warm, fuzzy feeling from the liberal platitudes of Cry Freedom (Richard Attenborough, 1987) or Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme, 1993) but would anybody try to argue seriously that they are better films than unpleasant, even depressing works such as The Birth of a Nation (D. W. Griffith, 1915), Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, Leni Riefenstahl, 1935) or Mandingo? Similarly, The Accused (Jonathan Kaplan, 1988) has admirable intentions but as a film, it pales next to Straw Dogs.

The way the biker scene plays out, going from violence to tenderness and back to violence (as Bennie kills both men) is a pattern that is repeated often in the film. Consider the calm of the opening scene, shattered by men with guns or the romantic interlude as Bennie and Elita have a picnic, this choppily-edited but genuinely affecting scene interrupted as the car containing a couple of bounty-hunters drives slowly past. The scenes between the lovers are some of the warmest in all of Peckinpah: their horseplay in bed, Bennie flicking her with a towel until she gets up or his beaming smile when she praises his Spanish. There are a couple of times when Oates plays it so intensely that it is hard to watch, such as his grudging proposal of marriage as Jerry Fielding’s intrusive score alternately evokes romance and gloomy foreboding or the desperate look he gives Elita as she sits under the shower. Bennie can’t commit to her because in Peckinpah’s world, men love death more than they love women: in an interview, the director posed the following question:

Another rural idyll

What is the motivation of a man who becomes a professional soldier or an outlaw? I believe it is almost always a love of violence, a deep love that proves more powerful than the lure of money, of women and of all other passion. (In Butler 1979: 22)

It is, no doubt, significant that Peckinpah, Oates and Bennie all served in the military and the aforementioned doubling of Elita and Alfredo, with Bennie telling the head that ‘a friend of ours tried to take a shower in there’, is strongly suggestive of this ‘deep love’. It is that kind of movie, where a man’s only friend is a fly-blown head and nobody can get clean (notice how Bennie doesn’t say she took a shower but she ‘tried to take a shower’). The film’s narrative can be regarded as one long, slow descent to the grave: consider their journey from the city to a plush hotel to a dump and onwards to a grave to lots of murders to death. As Chris Petit has remarked, this is a film completely devoid of suspense, events unfolding with a grim inevitability. This is borne out by the aforementioned cryptic dialogue, such as when Bennie tells Elita ‘I wanna go someplace new’, or his words as he leaves El Jefe’s compound with the head, saying, ‘Come on, Al, we’re going home.’ What home? The hole in the ground, where Elita waits with the rest of Al?

‘Come on, Al, we’re going home’

GETTING ALFREDO: PARODY AND CULT MEANING

Of course, it may all be a joke. A provocation, a parody, a piss-take. Jay Cocks, one of the few critics to give the film a positive review at the time of its release, thought it self-lacerating:

[a] straight-faced parody … Peckinpah means this movie to outrage; it is a kind of calculated insult mixed with generous doses of self-satire … It is like a private bit of self-mockery, a sort of ritual of closet masochism that invites, even challenges, everyone to think the worst. Many will. That is part of what Peckinpah was after, and his success in getting it is the most disturbing element in this strange, strangled movie. (1974)

Cocks compared it to John Huston’s wacky Beat the Devil (1954), a film so derided that even its star, Humphrey Bogart, declared that ‘only phonies like it’ (quoted in von Busack 1998). Cocks, who knew Peckinpah personally and was well-schooled in his work, is an extreme example of what Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik refer to as the smart or avid fan. Such fans:

Combine in-depth factual and theoretical knowledge about films with an informed understanding of narrative and stylistic sophistication. They revel in the number of references, interpretations and connections their knowledge allows them to make and by doing so they equip films with multiple subtexts. (2003a: 6)

For such a viewer, Alfredo Garcia is rich in allusion, full of injokes and autobiographical asides. For an outsider, it is easily dismissed as so much self-indulgent crap. Similarly, Beat The Devil is, for the avid Huston fan, a wildly funny deconstruction of the same director’s The Maltese Falcon (1941), while to the unconverted, it is a dismally unfunny mess.