CHAPTER TWO

Having crossed the English Channel, the largest naval force assembled to date filled the Bay of the Seine off the Normandy coast. The bay stretches 62 miles (100 km) from the Cotentin Peninsula in the west to the city of Le Havre at the Seine estuary on the east. Within the Bay of the Seine, the majority of the Allies’ invasion vessels began arriving on the morning of June 6, at approximately 5:00 a.m. to begin the assault on the Normandy beaches. By the end of the day, 6,939 vessels had participated in the invasion.

First to reach the Bay of the Seine were minesweepers, arriving in the area near midnight. For the next five hours, these wooden warriors swept channels for the bombardment ships that were soon to arrive. Nearly 350 minesweepers, motor launches, and other support vessels cleared 10 channels, each 400 to 1,200 yards wide, for the amphibious assault forces. They then escorted the big-gun ships of the bombardment force as they steamed into position.

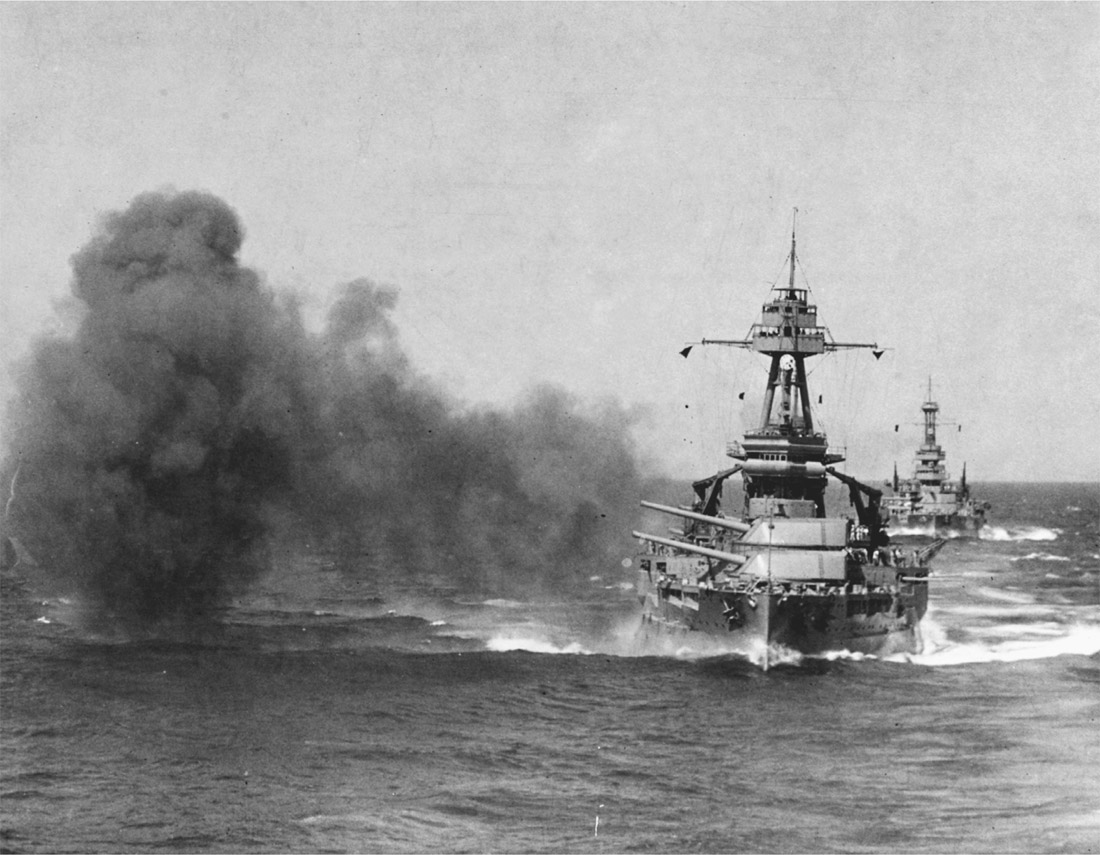

While the amphibious ships were deploying landing craft and preparing to send boats ashore, the guns of the bombardment force opened fire. The Eastern Task Force (British) consisted of battleships HMS Warspite and Ramilles; cruisers HMS Ajax, Argonaut, Mauritius, and Orion; monitor HMS Roberts; and other ships accompanied by thirty-seven destroyers. The Western Task Force (American) Bombardment Force A consisted of the battleship Nevada (BB-36), cruiser Quincy (CA-71), monitor HMS Erebus, light cruisers HMS Black Prince and Enterprise, and Dutch gunboat HNLMS Soemba, plus six destroyers and twenty-one support craft. Bombardment Force C comprised the battleships Texas (BB-35, force flagship) and Arkansas (BB-33), cruiser HMS Glasgow, and French light cruisers Georges Leygues and Montcalm, plus twelve destroyers and thirty-seven support craft. The Western Task Force engaged targets at and behind Omaha and Utah Beaches, with Texas concentrating her fire on the gun emplacements at Pointe du Hoc.

At 5:05 a.m., the German 210mm (8.25-inch) coastal defense guns at Saint-Marcouf, in the Utah Beach sector, placed the American destroyers Corry (DD-463) and Fitch (DD-462) under fire. Corry engaged the shore battery with her 5-inch guns. At 6:30 a.m., she was struck amidships in the engineering spaces. Her rudder jammed, and she began to circle while taking on water fast. Oddly enough, although her commander, Lt. Cdr. George D. Hoffman, reported that she had been struck by an artillery shell, the official record reflects that she was sunk by a mine. Fitch and other ships in the area were able to rescue all but one officer and twenty-two sailors.

British, Canadian, Czech, Dutch, Free French, New Zealanders, Norwegian, Polish, and South African soldiers and sailors participated in Operation Neptune and the invasion of Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches at the eastern end of the Bay of the Seine. On the west end of the bay, American troops went ashore at Omaha and Utah Beaches. The advance up Utah Beach was easy compared to the relatively difficult terrain and withering enemy fire encountered at Omaha Beach. At Utah Beach during D-Day, American forces were able to put 23,250 men ashore along with 1,742 vehicles and 1,695 tons of supplies, with the loss of 197 men.

Omaha Beach was another story. The area had been divided into eight segments (from west to east: Charlie, Dog Green, Dog White, Dog Red, Easy Green, Easy Red, Fox Green, and Fox Red). German strongpoints guarded the beach exits, with the heaviest troop concentrations at Vierville (Charlie and Dog Green), Les Moulins (Dog Red and Easy Green), and Fox Green Beach, which faced two beach exits, one leading to Colleville and the other through the bluffs.

Rough seas swamped a number of landing craft, and a strong current coupled with low visibility pushed many assault boats off course, causing them to come ashore in the wrong area. Pre-invasion bombing had missed many of the German defenses due to poor visibility and the desire not to drop too close to American troops coming ashore. Stiff German resistance kept the invaders pinned down for hours. It was not until a number of tanks were able to gain the beach and begin engaging the defenders at close range that any progress was made.

As the second wave of men came ashore around 7:00 a.m., the tide was coming in, hiding beach obstacles, which in turn damaged or destroyed a large number of landing craft. Rough seas swamped a number of DUKW trucks as they attempted to wade ashore, and the narrow beach caused a traffic jam, forcing the beach master from the 7th Naval Beach Battalion to call a halt to further vehicle landings at 8:30 a.m., until the situation improved.

At 9:00 a.m., gunfire from destroyers offshore and tanks on the beach enabled comingled elements of the 3rd Battalion of the 116th Infantry Regiment (29th Infantry Division) and the 16th Infantry Regiment (1st Infantry Division) to climb the bluff and begin advancing inland from Fox Green Beach.

Down the beach, three companies of the 2nd Ranger Battalion were landing on a narrow strip of beach, preparing to assault the 100-foot-tall cliffs of Pointe du Hoc. Their objective was to destroy six 155mm cannon and remove the Germans from their high vantage point, which had a commanding view of both Omaha and Utah Beaches. As the Rangers worked their way up, naval gunfire support came from the destroyer Satterlee (DD-626), preventing German defenders from firing down on the men climbing up the cliff. Satterlee supported the Rangers throughout the day as they held the high ground. The Rangers’ objective, the six 155mm guns, had in fact been removed from the top of Pointe du Hoc to an area south of the coastal highway. Five of the guns were located and thermite grenades exploded in the breaches, destroying them.

By the end of the day, the Allies had established a beachhead and begun to move inland.

Until the harbor at Cherbourg could be taken, the Allies needed port facilities to efficiently bring men and materiel ashore. To this end, they brought a number of war-weary ships to Normandy, where they purposely sunk them to form artificial breakwaters; these ships were known as “gooseberries.” One gooseberry was built to shelter each of the landing beaches: Gooseberry 1 at Utah Beach (ten ships), Gooseberry 2 at Omaha Beach (fifteen ships), Gooseberry 3 at Gold Beach (sixteen ships), Gooseberry 4 at Juno Beach (eleven ships), and Gooseberry 5 at Sword Beach (nine ships).

On the shore side of the ships at Gooseberry 2 and 3, prefabricated concrete caissons, known as “phoenixes,” built in England and towed across the Channel, were sunk in position to form a more substantial port facility. The goose-berry and phoenix components formed “mulberry harbors,” of which two were constructed: Mulberry A off the shore at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer (Omaha Beach) and Mulberry B at Arromanches (Gold Beach). Inside the mulberry break waters, floating piers with roadways, known as “whales,” extended to pier heads, known as “spuds.”

Both mulberry harbors were beginning operations when, on June 19, a storm blew in and destroyed Mulberry A at Omaha Beach. Mulberry B, which became known as “Port Winston,” after the British prime minister, was damaged in the storm but subsequently repaired. Mulberry A was abandoned, and landing ship tanks (LSTs) were used to supply American forces until September 1944. As the Allies moved across France and Belgium, more permanent port facilities were captured and put to use.

The forward 14-inch/45-caliber guns of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) bombard the invasion beaches prior to men landing on Utah Beach on the morning of D-Day. As the troops moved off the beach, Nevada and other ships of the fire support task force lobbed shells onto German Army targets inland. The 14-inch (356mm) naval guns onboard Nevada , at an elevation of 15 degrees, could fire a 1,400-pound armor-piercing shell 23,000 yards (21,000 meters, or 13.06 miles). Caliber refers to the length of the barrel; thus a 14-inch/45-caliber gun barrel (14-inch diameter × 45 caliber) has a length of 630 inches, or 52.5 feet. With the breech, a 14-inch/45-caliber gun has an overall length of 53 feet, 6.5 inches (16.32 meters). NHHC 80-G-252412

Steaming off Utah Beach, LCT(R)-48 (Landing Craft Tank [Rocket]-48) is heading to reload its launch racks. Capable of firing more than 1,000 3-inch-diameter, 60-pound (27.2-kg) projectiles, these craft could saturate a beach with explosives in a matter of seconds. The LCT(R) was converted from a standard landing craft tank by sealing the bow door and adding an additional deck for the rocket racks. The space between decks (’tween decks) could hold 5,000 additional rockets. The boat was equipped with a Type 970 radar to give range to the target and for navigation. The Type 970 was an airborne 9-centimeter radar (known as H2X, with the antenna mounted upside down for maritime use). NHHC 80-G-252483

A convoy of LCI(L)s (landing craft infantry [large]) sails toward the D-Day invasion beaches, each with an Mk VI box kite (barrage balloon) deployed against enemy low-level strafers. In the foreground are the decks of the USS Ancon (AGC-4), an amphibious force command ship.

Ancon was built as a passenger steamship for the Panama Railroad Company and was launched on September 24, 1938. The US Army acquired the ship shortly after the war broke out, and she was transferred to the US Navy on August 7, 1942. Ancon participated in Operation Torch, putting troops ashore at Fedhala, French Morocco. A little less than a year later, Ancon served as the flagship for the Omaha Beach invasion.

The bottom photo looks from the bow of Ancon toward the invasion beaches, with LST-373 at right. LST-373 took part in the Sicilian occupation (July 9–15, 1943) and the Salerno, Italy, landings (September 9–21, 1943), followed by its presence, as shown here, supporting the Normandy landings. In December 1944, LST-373 was transferred to the Royal Navy and was redesignated HM LST-373. She then sailed to the Pacific Theater and supported all major operations, from Rangoon to Malaya, Singapore, and Bangkok. She worked to repatriate Allied POWs before being returned to the US Navy in March 1946. NHHC 80-G-231247 AND 80-G-231248

LCI(L)-217 makes her way across the English Channel with a kite balloon deployed. Eleven LCI(L)s were heavily damaged or sunk during the invasion, with another eighty-three severely damaged. This LCI(L) served the US Navy in support of the occupation of North Africa (March 27–July 9, 1943), then in the invasion of Sicily and operations up the west coast of Italy. After the Normandy campaign, LCI(L)-217 was transferred to the Royal Navy in November 1944. Following the conclusion of the war, the LCI returned to American ownership on March 14, 1946, and was sold to the French Navy five days later, on March 19. The French renamed her RFS L9046. NHHC 80-G-252368

Landing craft—in this case landing craft vehicle personnel (LCVP)—head back to their ship, LST-284 , after having discharged men and equipment on the invasion beaches. LST-284 saw service at Normandy and the invasion of southern France before being transferred to the Pacific Theater, where she supported the landings at Okinawa.

LCVPs were designed by Andrew Higgins of Higgins Industries in New Orleans, Louisiana, and more than 23,350 were built by the company and other contractors before the war ended. NHHC 80-G-252687

USS Bayfield (APA-33) was laid down at Western Pipe and Steel in South San Francisco, California, for the Maritime Commission on November 14, 1942, as SS Sea Bass. Launched on February 15, 1943, she was redesignated an attack transport. The ship was transferred from the Maritime Commission to the Navy in June 1943 and was operated by an all–Coast Guard crew. She is seen off the Utah invasion beach, with her LCVPs circling at the stern awaiting reloading while her forward deck cranes lower more boats into the water. An LST, LCI, and LCT can be seen in the background at right. NHHC 80-G-252391

While Allied troops continue to flood ashore on June 8, American senior officers observe landings on the beaches of Normandy from the decks of the cruiser Augusta (CA-31). From left: Rear Adm. Alan G. Kirk (US Navy, Commander Western Naval Task Force), Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley (US Army, Commanding General, US First Army), Rear Adm. Arthur D. Struble (holding binoculars US Navy, Chief of Staff for Rear Admiral Kirk), and Maj. Gen. Ralph Royce (US Army). NHHC 80-G-252940

Prior to the invasion, US Army and Navy officers gathered to watch units going ashore on the English coast. Standing to the right of Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley is Rear Adm. John L. Hall Jr. (US Navy), who led Amphibious Force O in support of US Army V Corps’ assault on Omaha Beach; Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow (US Army), commander of V Corps and the first corps-level commander to land on the European continent on D-Day; and Maj. Gen. Clarence L. Huebner (US Army), commanding officer of the 1st Infantry Division, “The Big Red One,” which assaulted Omaha Beach. NHHC 80-G-253483

Lying off Omaha Beach on D-Day, command ship Ancon (AGC-4), at right, with submarine chaser PC-564 slowly making its way toward shore. Headquarters units were dispatched from Ancon to the beaches as troops moved inland. NHHC 80-G-257287

The US Coast Guard provided sixty 83-foot cutters (83 feet, 2 inches in length, with a beam of 16 feet, 2 inches) to support Operation Neptune. The cutters were assigned to USCG Rescue Flotilla No. 1, based at Poole, England. Each displaced 76 tons, had a maximum speed of 20 knots, and was driven by twin 600-horsepower, eight cylinder in-line Sterling Viking II Model TCG-8 gasoline engines, displacing 3,619.1 cubic inches, which turned twin screws.

While on D-Day patrols, 83-foot cutters rescued 1,437 men and 1 woman. Two of the cutters were lost in the days following the June 6 landings; USCG-27 (83415) and USCG-47 (83471) were both lost in a storm on June 21, 1944, after contacting underwater wreckage from the invasion. NARA

The USCG-1 , formerly the 83300/ex-CG 450, escorted the first waves of landing craft into the Omaha assault area on D-Day morning. The crew of USCG-1 pulled twenty-eight survivors out of the English Channel from a sunken landing craft right off the beaches before 7:00 a.m. on D-Day. US COAST GUARD HISTORIAN’S OFFICE

The 83-foot Coast Guard cutter USCG-1 (83300/ex-CG 450) off Omaha Beach on the morning of D-Day, tied up to LCT (Mark VI)-549 and the attack transport USS Samuel Chase (APA-26). Samuel Chase was part of Assault Group 0-1, which landed the 1st Division (famous as “The Big Red One”) on the Easy Red section of Omaha Beach. US COAST GUARD HISTORIAN’S OFFICE

In the waters off Sword and Juno Beaches, two 52-foot-long midget submarines were waiting for the invasion fleet. They were not there to attack. The submarines were Royal Navy X-Class midgets that had departed England, arriving off the invasion beaches on June 1. X-20 and X-23 sat on the bottom during the day and surfaced at night to listen to the BBC for the coded message signaling that the invasion was coming the following morning. Early on the morning of June 6, both craft surfaced and hoisted a lighted mast that shone out to sea, essentially acting as lighthouses to aid landing craft in their approach to the beaches. AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

The German Army fought savagely on D-Day, and USS LCI(L)-553 and USS LCI(L)-410 are seen disembarking troops from the 16th Regimental Combat Team into the maelstrom on Omaha Beach’s Fox Green section. LCI(L)-553 struck two underwater mines approaching the beach and then was hit by a pair of German 88mm cannon shells. Raked by fire and unable to back her away from the beach, the crew abandoned ship and went ashore. NHHC 80-G-421287 AND 80-G-421288

Action on Omaha Beach as troops wade ashore from LCI(L)-412. The rise between the sea and shore provides little cover, but men hunker down as LCI(L)-412 ’s bow gunner engages the enemy with his 20mm cannon. Half-tracks have entered the water behind the soldiers to provide cover fire for their forthcoming advance. NHHC 80-G-421289

Soldiers make their way to dry ground, having stepped off the bow ramp of a US Coast Guard– crewed LCVP. Smoke and beach obstacles can be seen in the background. NARA/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2343

Smoke rises from devastated German positions as a rhino ferry, seen at center, brings men and vehicles from the Ninth Air Force’s engineers to Omaha Beach. The Engineer Aviation Battalions moved right behind frontline troops to scrape out emergency landing fields from the countryside as well as refueling and rearming strips for fighter-bombers supporting the advance. The rhino ferry was constructed by lashing together pontoons (6 × 6 feet each, then bolted together, six pontoons wide and thirty pontoons long); it was towed across the Channel by an LST and then cut loose as it approached the beachhead. The rhino then drove itself to shore using its twin Chrysler outboard motors. Troops, vehicles, and large amounts of ammunition were typical loads for a rhino ferry. The rhinos could also be tugged across the Channel empty, then used as barges to offload vehicles and supplies from LSTs. They were also used as piers, with an LST docking bow-on, lowering its ramp, and discharging vehicles to travel across the rhino and then onto the beach. NARA/US ARMY 51764AC

Aerial photo of the beaches at Grandcamp-les-Bains, France, east of Utah Beach, reveals its anti-invasion obstacles at low tide. Here the Germans used large logs topped with Teller mines to defeat boats approaching the beaches. At high tide, these would be unseen, hiding below the water’s surface. NARA/US ARMY 190653

Ninth Air Force B-26 Marauder medium bombers escorted by P-38s, P-47s, and P-51s were over the invasion beaches at first light to attack German positions at the five invasion points. Once the bombers had attacked their targets, the fighters remained to protect the invasion flotilla and attack anything that moved behind the beachhead. NARA/US ARMY 51697 AND 51988

Flagship of the bombardment force in the waters off Omaha Beach, battleship Texas (BB-35) turned its 14-inch, 45-caliber guns against Pointe du Hoc, firing 255 shells in 34 minutes. Her secondary 5-inch guns pummeled the beach area exit known as D-1. With Allied troops unable to break the German resistance along Omaha Beach, Texas closed to within 3,000 yards of the shore and began firing at nearly point-blank range to help break up German troop concentrations. Texas continued her fire support mission until June 8, when she retired to England to refuel and rearm. The battleship was back in action by June 11.

On June 25, Texas was again off the coast of France, this time bombarding targets near Cherbourg. In company with battleships Arkansas and Nevada , the three battlewagons sparred with the four 240mm guns of the Fermanville battery, 6 miles east of Cherbourg. Supporting the battleships were destroyers Barton (DD-722), O’Brien (DD-725), Laffey (DD-724), Hobson (DD-464), and Plunkett (DD-431). Minesweepers clearing a firing lane ahead of the larger ships were straddled by shells.

Around 12:20 p.m., Texas was struck by a 280mm shell, which hit the armored conning tower, killing the helmsman, Quartermaster 3rd Class Christen N. Christensen. Another 280mm shell struck her hull, but this one was a dud. Shortly thereafter, Texas knocked out one of the Fermanville battery’s four guns. At 3:00 p.m., all the ships retired; the battery was subsequently taken by ground troops on June 29. NHHC NH 63648

Fully loaded with troops from the 1st Infantry Division, LCI(L)-490 (left) and LCI(L)-496 approach Omaha Beach on D-Day during the first wave. Gunfire is impacting the beach, but there are few vessels or vehicles ashore at this point. Note the two LCVPs sailing out past the LCIs to pick up another load. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS SC 189987

All sorts of landing craft, including LCMs, LCI(L)s, and LCTs, can be seen headed for Omaha Beach during the morning of D-Day. At low tide, men of the 1st Infantry Division had to cover 300 yards of beach from the landing craft to the first ledge. From there, they had another 100 yards to travel before they could gain cover from the terrain. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS SC 189988

Soldiers from the 16th Regimental Combat Team look on from their LCVP as they near Omaha Beach. Mixed in with the LCVPs are DUKW amphibious trucks, and DUKWs can be seen onshore. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS SC189986

LCVP from attack transport Samuel Chase (APA-26) about to land, with a sailor standing on the ramp. The fact that he’s standing in the open indicates this photograph was taken later on D-Day. LCI(L)-553 , at left, was abandoned hours earlier. The truck at lower right has a sign warning those who will follow that the driver sits on the left side and the vehicle has no turn signals. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS SC189899

Two views of the tremendous number of ships employed during the invasion of just one beach, along with the destruction wrought by shore bombardments and aerial bombing. Hundreds of vehicles can be seen on the sand and along the beach exit roads. NARA/US ARMY 53469AC AND 53519AC

Another view of the Utah Beach area showing vehicles streaming inland from the beach exit. Fires burn houses and former German strongpoints. Of the LSTs grounded in the surf line, the ship at the lower left and parallel to the beach is unloading its cargo of vehicles in the lee of an empty LST. This seemingly odd positioning blocked the incoming surf from impacting vehicles as they drove down the bow ramp and onto the beach. NARA/US ARMY B-62605AC

The low terrain along the Utah Beach sector enabled men and equipment to stream inland once initial German resistance was broken. The volume of men and materiel coming ashore prevented the Germans from repulsing the invasion on the beaches. NARA/US ARMY 51579AC

Massive bomb craters can be seen in the foreground as LCIs approach Utah Beach. NARA/US ARMY 52281AC

A mass of vehicles crowd the beach as others move up the roadway to the interior of France. Nearly every square yard of land in the foreground has been marked with a bomb or shell hole, demonstrating the intensity of the pre-invasion bombardment and aerial bombing. NARA/US ARMY 58416AC

US Army vehicles can be seen leaving the beach and heading inland. Note the large amount of beach obstacles on the sand and in the surf line as well as the landing craft attempting to thread their way to the shore. NARA/US ARMY A-62605AC

On the afternoon of D-Day, Ninth Air Force B-26 Marauder medium bombers returned to attack targets behind enemy lines. Bombing at low altitude, the Marauders hit gun positions and troop strongpoints, as well as road and rail targets. This photograph of the Utah Beach area shows hundreds of bomb and shell craters. The road leading away from the beach is filled with Allied vehicles moving inland. NARA/ USAAF 52406AC

Aerial view of the Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer area of Omaha Beach, with the first airstrip (A-21C) visible behind the invasion beach. The chain of Liberty ships in the center of the photo were deliberately sunk to form a breakwater to shelter Omaha Beach. Known as mulberry harbors, they would enable the Allies to supply their troops ashore without having to assault the closest port, which was Cherbourg.

On June 19, a gale-force storm tore apart the mulberry harbors, rendering them useless and making the capture of Cherbourg a priority. Seven days later, Cherbourg fell to the Allies and became an important port throughout the remainder of the war. During their service, mulberry harbors enabled more than 12,000 tons of supplies and more than 2,500 vehicles to come ashore each day. NARA/US ARMY 72990AC

Numerical superiority in men, vehicles, and ships is dramatically illustrated in this photo of the invasion beaches at low tide. Every type of cargo ship can be seen in the background, while more than half a dozen LSTs unload. An LCT is seen high and dry in the center of the photograph, while truck and half-track convoys prepare to depart the beach. Identifiable LSTs are LST-532 (in the center of the view), LST-262 (third LST from right), LST-310 (at right, preparing to launch barrage balloon), LST-533 (partially visible at far right), and LST-524 . NARA/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2517

Omaha Beach after the siege had been lifted and LSTs were able to swarm ashore. Note the difference between the US-and British-operated LSTs: The Royal Navy ships wear their hull numbers in colored blocks and are painted in striped camouflage, while the American LSTs are painted a dark blue overall (known as Measure 21 camouflage). Identifiable LSTs on the beach are, from right, LST-312 , British LST-320 and LST-321 , LST-72 , an unidentified US Navy LST, British LST-324 , LST-311 , LST-49 , LST-373 , LST-47 , and two more unidentified LSTs. NHHC 80-G-46817

During unloading operations on the afternoon following D-Day, an explosion rocked the beach area as engineers destroyed German land mines. British LCT-996 is at the extreme right, stranded by low tide. British LCT-799 is alongside, just to the left; several other landing craft are also present. LCTs could carry up to ten tanks. NHHC 80-G-252257

Omaha Beach on the afternoon of D-Day with vehicles and a tank mired in the sand. Note the bodies in the foreground, yet to be collected by Graves Registration troops. NHHC 80-G-45714

A pair of LCMs approach Utah’s Green Beach two days after the invasion. Light can be seen through the roof of the house on the beach as DUKWs roam up and down the surf line. NHHC 80-G-252624

Carrying supplies to shore, an amphibious DUKW, christened Jesse James , wades ashore at, most likely, Utah Beach on June 11. Note how the cargo was lowered into the DUKW in nets, which will be retrieved by cranes on the beach. NHHC 80-G-252737

Members of the 9th Service Group, IX Air Service Command, about to go ashore from an LST on Omaha Beach in the days following the invasion. The shallow-draft LSTs could get extremely close to the beach for a vessel of their size. Note the 40mm cannon at the bow and that the LST has dropped anchor. NARA/US ARMY 61288AC

It’s all about weight and balance. LST-325 sits on the beach at low tide with the majority of her weight aft of midships, requiring a sand ramp to be built under her bow doors. The sand ramp enabled vehicles to be offloaded while the tide was out.

LST-325 made forty-three round-trips bringing supplies from England to France in support of Allied troops. She is most noted for the December 28, 1944, rescue of more than 700 men from the Royal Navy infantry landing ship Empire Javelin between Southampton, England, and Le Havre, France.

After the war, LST-325 was transferred to the Greek Navy on May 1, 1964 through the Military Assistance Program. The Greeks renamed her HS Syros (L-144) and sailed her for more than thirty years. She is now an operating memorial ship based in Evansville, Indiana (see appendix VI: Select D-Day Survivors). NHHC 80-G-252795

LST-138 unloads a portable photographic laboratory destined for a Ninth Air Force advance airfield to support the needs of frontline tactical reconnaissance squadrons. A US Army bulldozer pulls the tractor-trailer combination across the soft sand of Omaha Beach. Note that the RAF truck tractor wears the name Evelyn Ann. NARA/USAAF 56610AC

Multiple 40mm cannon point skyward on LST-325 as she and LST-388 unload at low tide. Note the guard between the rudder and the propellers to keep the spinning blades from contacting the sea floor. Also note the Danforth-style anchor at the stern of LST-325. This anchor could be dropped as the LST sailed onto the beach; then, as the tide rose, it could be reeled in, pulling the ship off the beach. NHHC 80-G-252797

Tons of supplies are seen sitting on Omaha Beach on June 15, as British LCTs lie parallel to the surf line. British LCT(A) (5)-2421 is identifiable behind LCT-555 in the center. LCVP X-19 in the foreground wears the name Angela and Cincinnati , Ohio , on her port side. DUKWs can be seen moving cargo among the various LCTs stranded on the beach. NHHC 80-G-252568

Fitted with raised air intakes, M4 Sherman Cannon Ball was from the 70th Tank Battalion, which waded ashore at Utah Beach on D-Day. The 70th lost nine of its forty-eight Shermans during the beach assault. Cannon Ball , seen here, dropped into an underwater shell hole and had to be abandoned during the invasion. She was later recovered and put back into service. NHHC 80-G-252802

Having routed the Germans, a Navy shore battalion moves into their former enemy’s slit trenches and bunkers behind the seawall. DUKW amphibious trucks can be seen maneuvering toward the beach exit, while an LCT and other landing craft in the background bring in supplies. NHHC 80-G-252734

Engineers from the US Navy’s 2nd Beach Battalion examine a pair of Leichter Ladungsträger Goliath (Sd.Kfz. 302/303a/303b) tracked mines. To the Allies, they were known as “beetles.” The beetles were tracked vehicles packed with explosives and were 4 feet long, 2 feet wide, and about 1 foot tall. They were remotely controlled by a wire, and the Germans intended to drive them out to detonate under a landing craft or Allied tanks. Two versions of beetles were built, differing in the size of the explosive (either a 30-pound/66-kg or 220-pound/100-kg charge). These beetles are being dismantled on Utah Beach on June 11. NHHC 80-G-252744

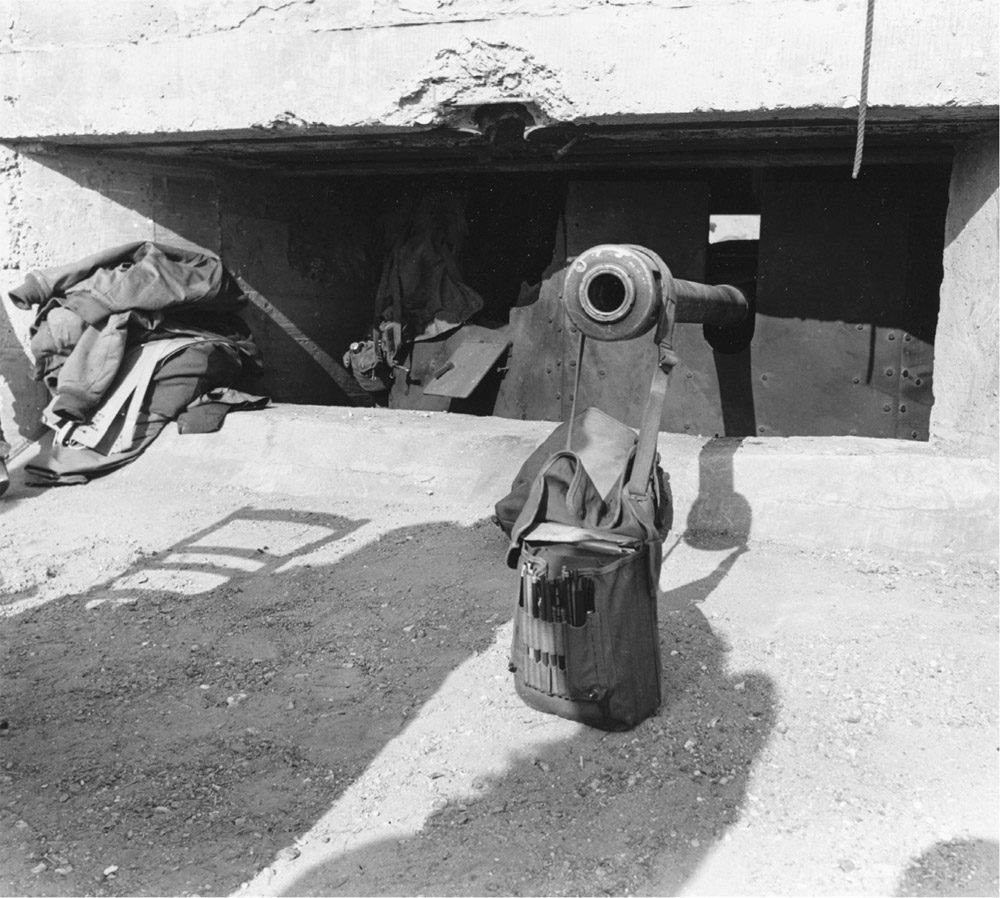

Although sited near Cherbourg and seen after capture by Allied troops on July 3, this concrete gun emplacement was typical of the coastal defenses engaged during the invasion. NHHC 80-G-254307

This gun in a German pillbox was destroyed by naval gunfire. Note the shell impact point above the German gun on the edge of the slit. An Allied shell clipped the opening, traveled into the bunker, and exploded, killing the gun crew and silencing the weapon. By June 11, this bunker was in use as a US Army command post. American field jackets can be seen at left, and a map case hangs from the gun barrel. NHHC 80-G-252574

The kill zone of overlapping fire is evident in this photograph taken from one of the German pillboxes overlooking Omaha Beach. A German 88mm gun could easily engage any of the landing craft seen at water’s edge, as well as many of the ships in the distance. NHHC 80-G-253256

Looking down on the east end of Omaha Beach shows a line of destroyed LCVPs and LCPLs in the foreground, including a British LCT-735 (closest to the camera at the shoreline). The old British battleship Centurion is seen in the distance, just to the left of center. Centurion was sunk to form part of the breakwater. NHHC 80-G-286425

Looking down on the east end of the mulberry harbor protecting Omaha Beach shows the breakwater of sunken ships in the distance. On the beach, unloading operations continue with LCT-149 , at left, and LCT-195 , near the center of the image. Note seamen sitting with their gear in the center foreground and the Royal Navy vehicle at left. NHHC 80-G-286424

Men from the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion look down on Omaha Beach. The unit is moving inland to carve out emergency landing strips and refueling and rearming airfields for the Ninth Air Force fighter-bombers that are supporting troops as they fight across France. NARA/US ARMY 76705AC

A combat cameraman from the Ninth Air Force photographed this view of Omaha’s Easy Green Beach from the hills near Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, site of the first emergency airfield on French soil. Barrage balloons protect the assembled ships from low-flying German aircraft. NARA/US ARMY 51676AC

Pointe du Hoc had a commanding view of both Omaha Beach on the east side and Utah Beach on the west side. Allied air forces dropped more than 1,500 bombs on heavily fortified Pointe du Hoc. The bombing caused the Germans to remove the six 155mm cannon stationed there; however, its importance as an observation post was not lost on the Allies. They intended to take the prominent land feature with three companies of Rangers (2nd Ranger Battalion, Companies D, E, and F), who were to scale the 100-foot cliffs and secure the point.

Twelve landing craft and four DUKW trucks carrying 100-foot ladders were dispatched to assault the point. En route, two of the landing craft carrying supplies were sunk, one of the DUKWs went down, and a landing craft filled with Rangers was sunk, with only one survivor.

After landing and scaling the cliffs while taking high numbers of casualties, the Rangers secured the top of the point and then set off to find the guns. Five of the six 155mm cannon were found and destroyed by throwing thermite grenades down the barrels.

The Germans counterattacked on the night of June 6/7 and throughout the next day. It was not until June 8 that the Rangers were relieved and the area secured. NARA/US ARMY 52237AC

More akin to the lunar landscape than a beach in France, this view shows the devastation wrought by large-scale bombing and naval bombardment. An M29 Weasel is parked in a shell hole below grade to protect it from shell or bomb fragments, while barrage balloons have been assembled and inflated and are awaiting deployment. NARA/US ARMY 72624AC

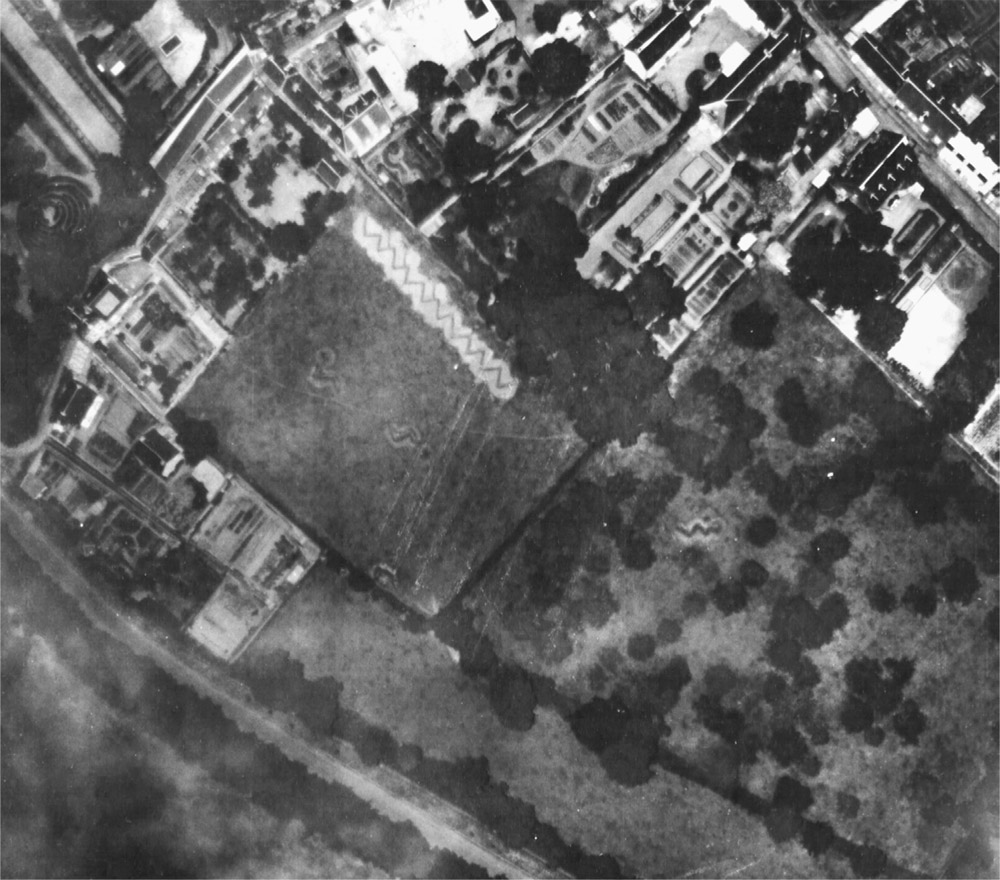

German fortifications are seen in an early-morning aerial photo near St. Lô, France. Shot with an electronic flashbulb developed by the Air Technical Service Command and General Electric, the flash was effective at altitudes in excess of 500 feet. Three antiaircraft gun emplacements can be seen below the trenches. NARA/US ARMY 61566AC

A fully loaded rhino ferry heads for the invasion beach under its own power. The shallow-draft barges could literally beach themselves at water’s edge and discharge vehicles onto the sand. Here a mix of 2.5-ton trucks and trailers is moving forward. Notice the coxswain at the helm (in the center of the photo) surrounded by short railings, the 20mm antiaircraft gun, and the crew keeping a vigilant watch near the port rail. NHHC 80-G-59400

Looking to sea on June 10 shows a nearly empty rhino ferry with its loading ramp down, and a fully loaded rhino crossing in the background. LCT-580 , beached at right, demonstrates the value of the shallow-draft rhinos, which enabled them to get farther up the beach to deliver men, vehicles, ammunition, and food supplies. Dozens of Liberty and Victory cargo ships obscure the horizon, and barrage balloons dot the sky while DUKW amphibious trucks can be seen shuttling supplies up the beach. NHHC 80-G-252647

By June 12 the fighting had moved inland, away from the coast, a fact illustrated by the relaxed demeanor of the sailors on LCI(L)-95 ’s gangway. LCI(L)-95 was part of LCI Flotilla 10, an all–Coast Guard flotilla. For Operation Neptune, the twenty-four Coast Guard LCI(L)s of Flotilla 10 were reinforced with the addition of twelve Navy-crewed LCI(L)s. Eighteen supported the invasion of Omaha Beach; the remaining eighteen were focused on Utah Beach. At Omaha Beach, four of the flotilla’s LCI(L)s— LCI(L)-85 , -91 , -92 , and -93 —were destroyed and a number of others heavily damaged.

Coast Guard Lt. Robert M. Salmon, commanding officer of LCI(L)-92 , was awarded the Silver Star for his actions on Omaha’s Easy Green Beach. His citation reads: “For gallantry as commanding officer of a US LCI (L) while landing assault troops in Normandy, France, June 6, 1944. He pressed the landing of troops despite the mining of his vessel, a serious fire forward, and heavy enemy gunfire. He supervised the unloading of troops, directed the fire fighting despite the loss of proper equipment and exhibiting courage of a high degree remained with the ship until it was impossible to control the progress of the fire and it was necessary to abandon ship over the stern. After abandoning he directed a party searching for fire fighting equipment and subsequently fought the fire on another LCI (L) and assisted her commanding officer until she was abandoned.” NHHC 80-G-252789

The Landing Craft Support (Small) seen here on June 12 were used to support commandos, Army Rangers, and other small parties; in this case the boat is flying the pendant of a survey party. Although designated Landing Craft Support (Small), the boats were armed like a PT boat, with a pair of twin 0.50-caliber machine guns mounted in turrets on each side of the wheelhouse. One LCS(S) was lost on Omaha Beach on D-Day. NHHC 80-G-252685

An 80-foot-long Elco motor torpedo boat, more commonly known as a PT boat, escorts a troop ship across the English Channel. One PT boat was lost during Operation Neptune, coincidentally an Elco 80-foot boat, and that was PT-505. On the night of June 7, PT-505 was chasing down what it thought was a submarine periscope in the waters off the Saint-Marcouf Islands, approximately 5.25 miles (8.4 km) off the coast of the Utah landing beach.

Just as the boat’s skipper, Lt. William C. Godfrey (USN), was about to give the order to drop a depth charge on the suspected submarine, the PT boat struck an underwater mine. The boat’s stern was lifted out of the water, and when it crashed back on the surface, both torpedo warheads broke loose and went over the side, a depth charge escaped its rack and went down, the engines were thrown from their mounts, and the boat was a mess. Two men were injured in the explosion.

PT-507 came to the boat’s aid and took her in tow. Lieutenant Godfrey transferred the valuable radios and radar set to PT-507 along with other equipment to lighten his boat. PT-507 towed the crippled patrol boat to one of the Saint-Marcouf Islands, where the boat was beached and the hull patched. Once seaworthy again, PT-505 was towed back across the Channel to Portland, England by PT-500; the craft finally arrived on June 11. NHHC 80-G-254261

Sailors watch as a jeep drives from inside LST-282 into the bay of an LCT that will transfer it to the Omaha beachhead. The 20mm antiaircraft guns on both sides of the cargo well have additional ammunition magazines at the ready, while the LST’s 40mm bow gun points skyward.

After supporting Operation Neptune, LST-282 was transferred to Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France that began on August 15, 1944. Near the invasion beach off Boulouris, France, LST-282 was struck by a German remote-control bomb, thought to be a Henschel HS-293. The explosion killed eleven men outright; thirty-nine more were unaccounted for. LST-282 burned and was beached on Cape Dramont, France, and later scrapped in place. NHHC 80-G-253137

LST-21 unloads British Army trucks and an M4 Sherman tank on the afternoon of D-Day. The LST has docked to a rhino ferry that is being used as a pier. Later in June, LST-21 carried a number of railcars across the English Channel. Engineers had laid a rail line to the beach, and the LST’s bow ramp was fitted with the same. The railcars were connected and came off in-train. After Operation Overlord, LST-21 supported Operation Dragoon in August 1944. NHHC/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2370

Eight DUKWs make their way to the Normandy shore loaded with supplies. Cranes have placed nets loaded with everything from food to ammunition into the cargo compartment of the amphibious trucks. NARA

A US Army Air Forces 23rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron (PRS) portable darkroom comes ashore from an LST. The 23rd PRS had served in the Mediterranean Theater beginning in September 1943. The unit was stationed in Tunisia, on the Italian mainland, Sardinia, and Corsica before moving to Y-23, Valence Airfield, France, as Allied troops marched toward Germany. NARA/US ARMY 58710AC

LCT(5)-8 was laid down at the Manitowoc Ship Building Company in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, on July 15, 1942. Delivered to the US Navy on September 5 of that year, the landing craft was transferred to the Royal Navy through the Lend-Lease Program on September 28. The Royal Navy redesignated the craft HM LCT-2008 and operated the tank landing craft in the Mediterranean Theater until early 1944, when it was reverse lend-leased to the US Navy. Redesignated as Landing Craft Tank (Armored) 2008 (LCT[A]-2008), this vessel was assigned to the LCT Gunfire Support Group. Sixteen LCT(A)s supported the landing at Omaha Beach, and eight delivered tanks to Utah Beach. Here, LCT(A)-2008 is seen transporting troops from a ship to shore on June 7, 1944. NHHC 80-G-252719

On June 7, Royal Navy LCT (Mark VI)s LCT-515 and LCT-1048 offload men and equipment from the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion at Omaha Beach. Note the CCKW truck with a Browning 0.50-caliber machine gun in an antiaircraft mount and the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion bulldozer coming ashore. NARA/US ARMY 76708AC AND A-76710AC

As territory near the coast fell and the threat of enemy shore fire was eliminated, minesweepers continued their work clearing the area of undersea explosives. Here a US Navy minesweeper (designated “YMS,” for auxiliary motor minesweeper) detonates a pair of German undersea mines near the approaches to Cherbourg Harbor. NHHC 80-G-256041

Aerial view of the Gold Beach area, where XXX Corps of the British Army, supported by troops from the Netherlands and Poland, came ashore to face the German Army’s 352nd Infantry Division as well as the 716th Static Division. Within the boundaries of Gold Beach, the Germans had two large coastal batteries at Longues-sur-Mer (four 150mm guns) and Mont Fleury (four 122mm guns), which were priority targets of the Allied forces. Bombers had tried to silence these positions the night before, but it took soldiers on the ground to overwhelm the batteries. NARA/US ARMY 53519AC

Early during the invasion of Omaha Beach, LCI(L)-85 struck a German underwater mine and was hit by more than twenty-five shells from coastal defense batteries. The landing craft infantry, crewed by US Coast Guard members, is making its way toward the attack transport Samuel Chase (APA-26), where she will offload her crew. NHHC 26-G-06-10-444

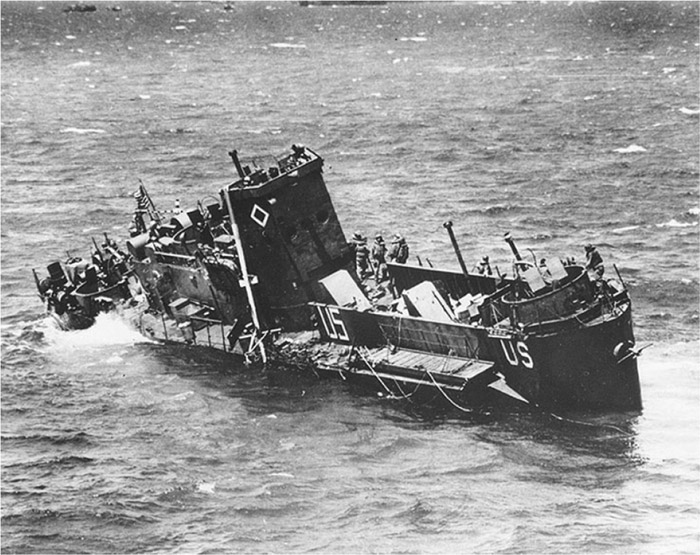

The Auk-class minesweeper Tide (AM-125) was assigned to Minesweeper Squadron A, tasked with clearing the sea in the vicinity of Utah Beach on D-Day. The following morning, as she was securing her minesweeping gear, Tide contacted a mine that broke the ship’s back and killed her commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. Allard B. Heyward. PT-509 (left) and minesweeper Pheasant (AM-61), at right, stood by to rescue survivors. The minesweeper Swift (AM-122) tried to tow Tide to the beach, but she broke in two and sank immediately. NHHC 80-G-651677

In the hours after the minesweeper Tide sank, the view off Omaha Beach on the morning of June 7 showed more stricken ships. LCT(6)-714 from Flotilla 26 struck a mine and is seen with her bow pointing skyward as another crippled LCI, most likely from Flotilla 10, sits on the beach. NHHC 80-G-252437

At 4:00 on the morning of June 10, Liberty Ship Charles Morgan was struck by a 500-pound (226.7-kg) bomb, which impacted the number-five cargo hatch, blowing off the cover and rupturing the main deck. One member of the ship’s crew and seven members of her gun crew were killed in the attack. Hull plating on the ship’s port side was opened to the sea from the number-four hold aft to the auxiliary steering engine room. Moored in 33 feet of water, Charles Morgan ’s stern settled to the bottom. Attempts were made to salvage the ship, but the damage was too extensive. LCT-474 and the fleet tug Kiowa (ATF-72) are seen alongside, rendering aid. NHHC 80-G-252657 AND 80-G-252655

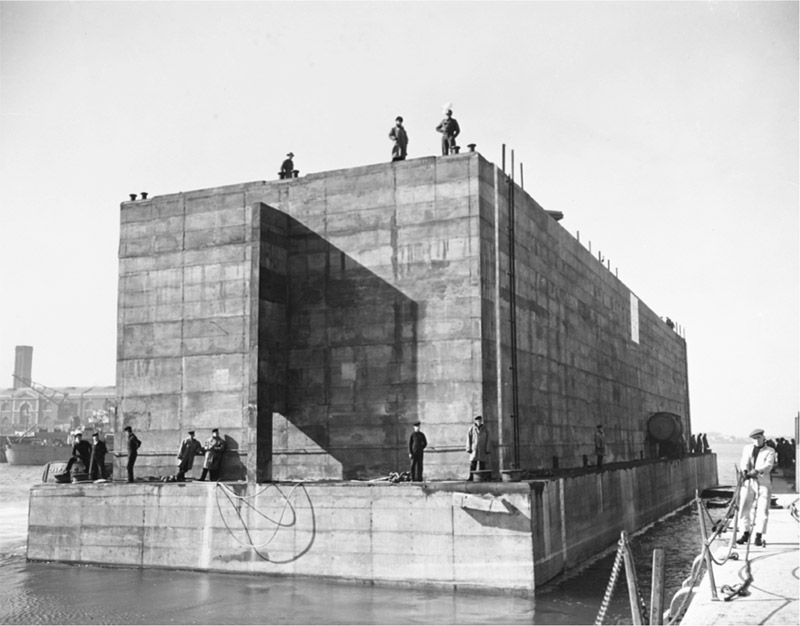

This phoenix caisson, built at southern England’s Portsmouth Dockyard, is positioned for its tow across the Channel, where it will help form a breakwater for the mulberry artificial harbors. More than 210 of the phoenix caissons were built in different sizes, the largest 200 feet long, 60 feet tall, with an overall weight of 6,000 tons. Two mulberries were planned—one off Omaha Beach (known as Mulberry A) and the other, Mulberry B, known as “Port Winston,” to supply the British, Canadian, and Free French troops at Gold Beach near Arromanches-les-Bains, France. Mulberry A was wrecked in a storm on June 19, while Mulberry B/Port Winston was in service for nearly 10 months, bringing more than 4 million tons of supplies, 2.5 million men, and more than 500,000 vehicles ashore. NHHC 80-G-251981

US Army oceangoing tug ST-759 maneuvers an unidentified Liberty ship into position to be sunk to form a gooseberry breakwater. Gooseberry breakwaters were constructed at Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches, numbered 1 to 5, respectively. Vessels identifiable in the background are LCI(L)-86 (center), British LCT-930 (right), and British LCT-763 (extreme right). NHHC 80-G-286402

Work to clear the beaches of German obstacles and mines got underway as soon as the fighting moved out of range. This photograph of the Omaha Beach area was taken on June 11 and shows a pile of “Czech hedgehog” anti-invasion steel obstacles. The hedgehogs take their name from their original location along the German–Czechoslovak border and were first seen in 1935–1936. The line of ships on the horizon is a gooseberry breakwater consisting of fifty-five ships purposely sunk to provide a breakwater protecting Omaha Beach. NHHC 80-G-252753

A pontoon causeway sits on Omaha Beach at low tide on June 12. The line of ships in the distance forms part of the gooseberry breakwater. The tidal range of the Normandy beaches during the war was 22 feet. NHHC 80-G-252793

Omaha Beach fortifications with antitank barriers and barbed wire seen from German positions behind barbed-wire defenses. Note the depth of the anti-invasion defenses at low tide. The invasion fleet rides at anchor in the background. BUNDESARCHIV BILD 101I-493-3363-13

A wide variety of cargo and obsolete military ships were sunk to form the gooseberry breakwaters to protect the invasion beaches. Photographed from a low-flying Ninth Air Force Martin B-26 Marauder, the scene shows nine Liberty ships in position as a protecting screen for vessels unloading on the beach. Additional block ships (code-named “corncobs”) would be brought in to expand the breakwater in the coming days. NARA/USAAF 54684AC

Nearly every type of vessel supporting the invasion can be seen in this photo of the gooseberry breakwater off Omaha Beach. Everything from Liberty cargo ships to rhino ferries plies the waters moving supplies to the beachhead. At this point, fifteen Liberty ships have been sunk to form the gooseberry breakwater, with more ships to come. NARA/USAAF 54577AC

Midday on D-Day, Coast Guardsmen rescue survivors from the sea. To the right, behind the rescuers, appears to be a minesweeper. NHHC/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2375

An LCM (landing craft mechanized) brings wounded to a transport ship for medical attention. Most appear to be ambulatory; however, transferring the wounded from sea level up to the ship’s main deck often required using cranes. NHHC/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2386

The sinking Coast Guard– manned USS LCI(L)-85 comes alongside Samuel Chase (APA-26) to transfer her survivors after she struck a mine and was hit by German shells off Omaha Beach on D-Day. A wartime censor has obscured the face of the soldier lying on the stretcher; a deceased soldier to the right has his head and face covered with a jacket. NHHC/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2344

A life cut short: An American soldier lies where he fell during the initial assault on Omaha Beach. Based upon his location far from the seawall, he may have drowned while exiting his landing craft. An M1 Garand and an M1903 rifle lie near his feet. Note how the Germans used tree trunks as well as Czech hedgehogs as anti-invasion obstacles. NHHC/US COAST GUARD 26-G-2397

The cost of war captured on film on Omaha Beach, D-Day, June 6, 1944. These men were members of the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. Some of the men have been covered by life belts, while a box shields the face of another dead soldier. NHHC/SIGNAL CORPS SC 189924

Wounded soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, await evacuation off the beach to troop ships and more intensive medical care after they drove the Germans from Omaha Beach. NHHC/ SIGNAL CORPS SC 189910

Captured German soldiers march out on June 12 to waiting ships that will take them to captivity. Their capture at Normandy essentially guaranteed these men would survive the war. Prisoner of war camps in England, Canada, and the United States warehoused captured German soldiers for the duration of the war. The Allies took 47,000 prisoners in June and 36,000 in July, with 150,000 captured in August 1944. NHHC 80-G-252828