CHAPTER THREE

The end of the day on June 6 saw the Allies firmly ashore, but in a tenuous position. Assault troops from the beaches were holding ground up to 5 and 6 miles inland. To make the advance more difficult, the Germans had flooded the low-lying areas behind the beaches, turning many of the fields into swamps.

The first link between American seaborne forces and airborne infantry took place at Pouppeville, about 1 mile in from the coast. The 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, was dropped off course and had to regroup. Only able to locate forty of the regiment’s men, Lt. Col. Julian J. Ewell pressed ahead to take the village of Pouppeville, which sat across one of the roads, known as Exit 1, leading across the flooded fields and inland. A force of little more than sixty men from the 1058th Grenadier Regiment from the German 91st Infantry Division held the town and put up fierce resistance. The Grenadiers killed eighteen Americans and lost twenty-five of their own, with another thirty-eight Grenadiers surrendering around noon. The 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, which had come ashore at Utah Beach, joined the 501st at Pouppeville to make the first seaborne/airborne troop connection of D-Day.

The 8th Infantry Regiment and other units of the 4th Infantry Division moved out to relieve the 82nd Airborne at Sainte-Mère-Église while the 2nd Ranger Battalion continued to hold Pointe du Hoc. Overnight, the 2nd Rangers fought a fierce battle with the German 914th Grenadier Regiment. The 914th nearly forced the Rangers back into the sea, reducing the ground the Americans held to a section of the cliffs only 200 yards wide. Twenty-three men from the 5th Ranger Battalion were able to join the 2nd Rangers during the night to help hold off repeated German counterattacks. On June 7, the Rangers were supplied from the sea by a pair of landing craft that brought food, water, and ammunition, but no fresh troops. It took another full day of fighting before men from the 2nd and 5th Rangers, the 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment, and the 743rd Tank Battalion were able to break the stalemate and relieve the Rangers. More than 125 Rangers were lost assaulting and holding Pointe du Hoc.

To the east of Omaha and Utah Beaches, the British and Canadians were having just as hard a time with the Atlantic Wall’s defenses. At Gold Beach, the British met very light resistance and were able to move inland fairly fast. Free French and British Commandos moved off Sword Beach quickly and were able to take Hermanville and Ouistreham before noon. However, the amount of Allied troops and vehicles landing in subsequent waves choked the narrow French country roads and brought the advance to a halt, completely destroying the plan to take the town of Caen by midnight. Shortly thereafter, the British Suffolk Regiment ran into the German strongpoint known as WN17 (or to the British as the Hillman Fortress) near Ouistreham, home to the 736th Grenadier Regiment. It took until 8:00 on the night of June 6 to rout the Germans from the complex.

While land troops were slowly advancing, capturing ground from the Germans, Allied engineer battalions were also ashore and busy scraping French soil. They were turning farm fields into airfields to provide the infrastructure needed to maintain air superiority to protect Allied troops. The Americans sent two airborne aviation engineering battalions and sixteen engineer (aviation) battalions, while the British landed five airfield construction groups and four airfield construction wings. By the time all these units were ashore, they counted nearly 64,000 men—all dedicated to building infrastructure for Allied aircraft.

Engineers built five different types of airfields, each to meet a different need of the Allied air forces. First to be carved out of the countryside were a series of emergency landing strips: scraped earth, level, and a minimum of 1,800 feet long—just enough to give a pilot in a damaged aircraft a safe haven rather than tempting fate by trying to cross the English Channel in a marginally airworthy plane.

The next level of airfield was built to increase the amount of air cover provided to ground troops. Rather than having a fighter/bomber fly from its base in England, across the Channel, and then to the target—a minimum of thirty minutes flying time each way—refueling and rearming strips were built to service aircraft and get them back into the action as soon as possible. Fighters would begin their day in England, attack targets in France, refuel and rearm at a local strip, and continue flying sorties until it was time to retire across the Channel for the night. The third type advance landing grounds, had dispersal areas large enough to accommodate two squadrons for extended periods, which could then be rotated out with fresh squadrons. These airfields were larger, more permanent facilities, able to accommodate fifty-four aircraft, and provided all the support that would be found on bases back in England. Hard-surface, all-weather airfields took the longest to construct, as they were much larger facilities with paved runways.

Operation Overlord contained an aggressive schedule for the construction of airfields in the captured areas, and two were open for business on D-Day Plus One (June 7). As the airfields came online, each was given an identifier denoting which service was the primary tenant; American airfields were assigned an “A” followed by a number; British airfields were given a “B” and a number. Emergency Landing Strip 1 at Pouppeville, behind Utah Beach; B-1 at Asnelles-sur-Mer, inland from Gold Beach; and A-21C at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer were open for business by the end of June 7—the first of more than sixty constructed between D-Day and August 31.

A-21C was built by the IX Engineer Command’s 834th Engineer (Aviation) Battalion on top of the bluffs overlooking Omaha Beach between Les Moulins to the west and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer to the east. The strip was 3,400 feet long and was prepared in sixteen hours. The strip’s proximity to the invasion beaches enabled the battalion’s heavy construction and earth-moving equipment to go into action quickly. This airfield was immediately used by Troop Carrier Command C-47s to evacuate wounded back to hospitals in England within a matter of hours of a soldier’s being injured.

On June 12, the US First Army took the town of Carentan, the key to strangling German troops on the Cotentin Peninsula, which in turn leads to the port of Cherbourg. Following a brutal battle against superior Allied forces, Cherbourg and most of the surrounding areas surrendered on June 29. German resistance was determined, as repeated attempts to take Caen failed, and the city was reduced to rubble through aerial bombardment. When the buildings fell from exploding bombs, the rubble choked the streets, impeding Allied tanks while creating vast numbers of defensive positions for the Germans. After continued heavy fighting, the city was finally liberated on July 9. Simultaneously to the attempts to take Caen, Allied troops attacked St. Lô on July 3. The Germans resisted for more than two weeks before the Allies were able to dislodge the defenders on July 18.

Gen. Omar Bradley’s Operation Cobra, July 25–31, employing strategic bombers to pulverize German armor, essentially ended the Normandy Campaign and enabled the Allies to break out and begin the march across France. On August 1, the US Third Army under the command of Gen. George S. Patton was added to the battle. Patton’s troops marched into Le Mans on August 8, and soon German Army Group B, the Seventh Army, and the Fifth Panzer Army were surrounded between the cities of Falaise (27 miles/44 km south of Caen) and Chambois. Known as the Battle of the Falaise Gap, the Allies nearly annihilated Army Group B, breaking the back of German resistance in the region.

The loss of an estimated forty German divisions in Normandy between June 6 and August 15 enabled the Allies to drive across France and liberate Paris on August 25. There was more bloody, costly fighting ahead, but the Allies had opened a second front. The end for Nazi Germany was now only nine months in the future.

US Army Rangers rest atop the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc on the afternoon of June 8. The cliffs, which towered more than 100 feet above sea level, divided the Utah and Omaha landing beaches. On top of Pointe du Hoc were six 155mm guns, four in concrete casemates. The US Ninth Air Force bombed the area in April, and the Germans subsequently removed the guns. However, Allied planners wanted to prevent the Germans from using Pointe du Hoc as an observation post to direct fire down onto the invasion beaches. The 2nd Ranger Battalion was put ashore from British landing craft while the battleship USS Texas (BB-35), destroyer USS Satterlee (DD-626), and Royal Navy Hunt-Class destroyer HMS Talybont bombarded the top of the cliffs. The Rangers took the point and subsequently found five of the six 155mm guns, which they destroyed. It was not until June 8 that the Rangers were relieved; in the final tally, 135 of the 225 men who assaulted the cliffs were killed. NARA 80-G-45721

Street scene in Villers-Bocage showing the aftermath of strafing by RAF Typhoons and USAAF Thunderbolts. German tracked vehicles, guns, and trucks have been devastated by cannon shells and 0.50-caliber bullets raining down from Allied fighters. BUNDESARCHIV BILD 101-738-0267-21A

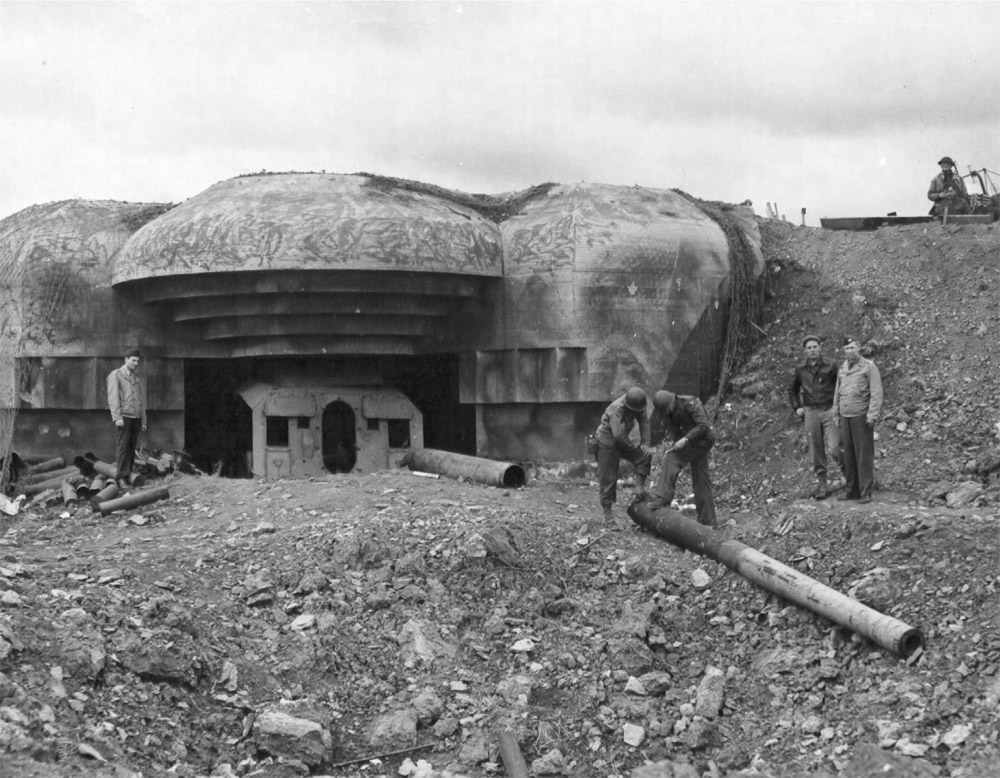

One of the four 152mm coastal defense guns at the Longues-sur-Mer battery is seen as engineers dismantle its gun tube. The battery was sited between the American Omaha Beach and the British Gold Beach objectives.

Hours before the invasion landings, RAF Bomber Command aircraft launched a massive raid against the coastal batteries at Fontenay, Houlgate, La Pernelle, Longues-sur-Mer, Maisy, Merville, Mont Fleury, and Pointe du Hoc. Exactly 1,012 aircraft were dispatched on the raid, with 946 making the drops. More than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped, of which 1,500 tons were aimed at the Longues-sur-Mer battery complex. Unfortunately, the majority of the bombs fell into the nearby town.

The US Navy battleship Arkansas (BB-33), the French cruiser Georges Leygues , and the Royal Navy cruisers Ajax and Argonaut all shelled the battery, with Ajax and Argonaut scoring direct hits, disabling three of the four guns. The single remaining gun continued to fire throughout the day, but on June 7 the battery’s crew of 184 men surrendered to the British Army’s 231st Infantry Brigade. NARA/ USAAF 72627AC

The Overlord plan called for the immediate construction of three emergency landing strips by the end of D-Day—a tall order considering the German opposition faced by Allied troops. Once available, C-47s of the Ninth Air Force Air Evacuation Unit began ferrying wounded soldiers, sailors, airmen, and German prisoners back to England and its rear-area hospitals. Note the barrage balloon and ships seen in the distance over the C-47’s number-one engine. Round circles in the C-47’s windows are gun ports, enabling soldiers on board to fire their weapons without fully opening the windows. NARA/USAAF 51923AC AND 51858AC

S/Sgt. George Blinkinsop of Clinton, Iowa, with clipboard, checks off a DUKW load of ammunition destined for Ninth Air Force fighters at a nearby advance landing field. The DUKW is a 6-wheel, 2.5-ton amphibious truck with a payload of 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) or 24 troops. The acronym stood for D (designed in 1942), U (utility), K (all-wheel drive), and W (dual-tandem rear axles). DUKWs could operate in fairly rough seas, and one was even driven/ sailed across the English Channel. NARA/USAAF 121821AC

The Ninth Air Force made extensive use of parapacks to resupply troops once on the continent. NARA/USAAF

A IX Troop Carrier Command C-47 delivers an Army jeep to a forward airfield. Note the spade and HQ markings on the jeep’s bumper. NARA/USAAF 52033AC

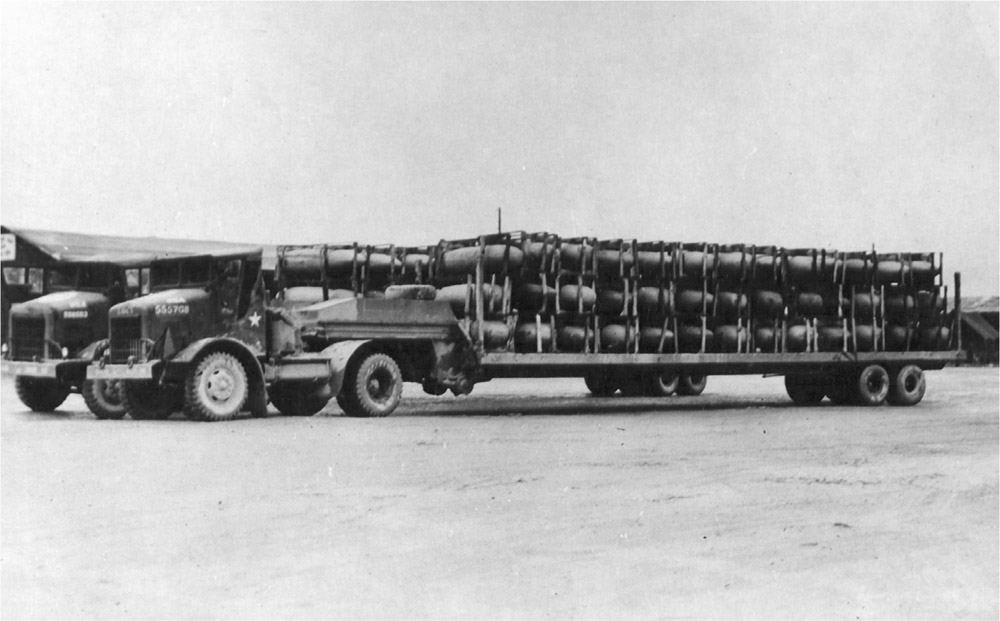

Auxiliary fuel tanks extend an aircraft’s range when escorting bombers or provide longer loiter times for fighter-bombers attacking road and rail traffic, convoys, bridges, and troop concentrations. Once a pilot has drained the fuel from the tanks, they are released, or dropped, to reduce aerodynamic drag on the aircraft. The only problem with dropping the tanks is that they are lost and thus not reusable. Here two semitruck loads of auxiliary fuel tanks have been brought ashore from a IX Air Service Command depot and are making their way to an advance airfield on the continent to aid in the air war against Germany. NARA/USAAF 55611AC

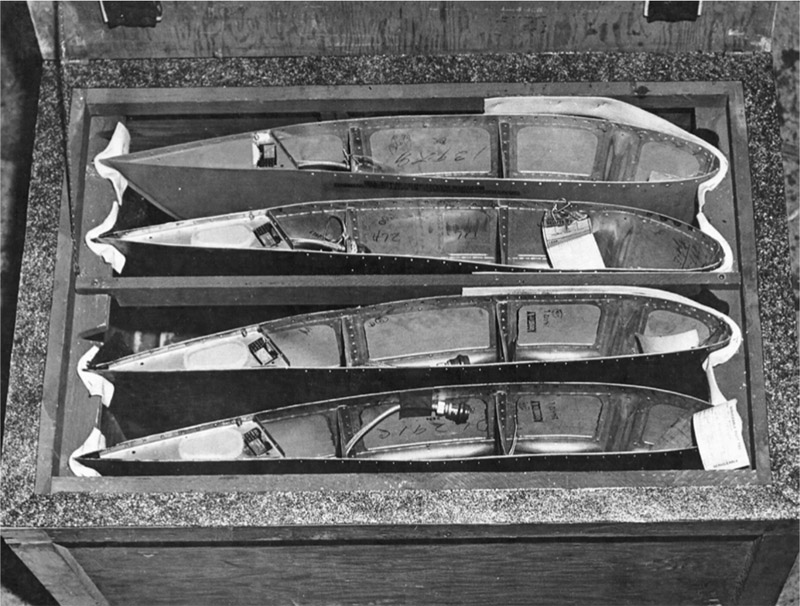

The Army Air Forces developed “compaks” to supply forward-deployed aircraft maintainers. Each compak was limited to 200 pounds; here four wing tips are shown. The removal of one wing tip does not impact the others, and once empty, the compaks could be returned to depots in England to be refilled. NARA/USAAF 81261AC

Aerial view of the airfield at Saint-Pierre-du-Mont (A-1) showing how close the field was to the coast and the flotilla of supply ships off the landing beaches. This photo was shot after the battle had moved inland, as P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts can be seen disbursed around the field. Pointe du Hoc is visible at the upper left side of the photo. NARA/USAAF 77061AC

The first Lockheed P-38 Lightning to land on the continent was P-38J 42-68071, seen touching down at Saint-Pierre-du-Mont (A-1) on June 10. Once the ground was taken after the invasion, this area was cleared for use as a crash strip to give damaged aircraft a place to land if they could not make it back across the English Channel to safety. Although graded earth in this photo, the field was later paved. The Piper L-4 to the right was used in the scout and artillery spotter role. NARA/SIGNAL CORPS 190118-S

As the battle moved inland, this C-47 from the 434th Troop Carrier Group, 72nd Troop Carrier Squadron, unloads supplies at a captured German airfield. This aircraft (fuselage code 6U-A) was factory-fresh, having been delivered to the Army Air Forces on April 27, 1944, and assigned to the Ninth Air Force on May 28, 1944. Its career was short-lived, however as 43-15663 was shot down on September 18, 1944, near Boxtel, Noord-Brabant, the Netherlands, while towing a glider during Operation Market Garden. NARA/USAAF 53615AC

A P-47 departs Saint-Pierre-du-Mont (A-1), shortly after the strip opened for business. Damaged fighters and fighter-bombers could land at the crash strip, built by the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion, without having to risk a flight across the English Channel. The efforts of the engineer battalions saved the lives of many aircrewmen in the days following the invasion. Fighters could also land at A-1 for fuel and ammunition to maintain longer patrols over enemy territory. NARA/USAAF 51862AC

Lockheed F-5B, the photo reconnaissance version of the P-38, is seen being serviced in England after overflying the landing beaches in France. This F-5B was flown by Lt. Col. C. A. Shoop, commander of the 7th Photographic Reconnaissance Group, Eighth Air Force, which was based at USAAF Station 234, RAF Mount Farm. Shoop and his group photographed the battle at Omaha Beach and provided photos to advise General Eisenhower of the invasion’s progress. Shoop ended his military career as a major general in the California Air National Guard. NARA/USAAF 54574AC

P-47D-6-RE 42-74629, Snuffy/Times A Wastin’ , at Saint-Pierre-du-Mont (A-1) during the opening days of the campaign. Snuffy/Times A Wastin’ was attached to the 48th Fighter Group, 492nd Fighter Squadron (fuselage code F4), based at USAAF Station 347/RAF Ibsley. On June 18, the 48th Fighter Group moved across the channel to Deux Jumeaux Airfield (A-4), France. The group concentrated on dive-bombing bridges, roads, and rail lines; by the time the campaign was over, the group had flown almost 2,000 sorties and dropped 500 tons of bombs. NARA/USAAF 76651AC

P-47D-22-RE 42-25683, Miss Lace , of the 48th Fighter Group, 492nd Fighter Squadron (fuselage code F4-C), seen at Deux Jumeaux (A-4) being serviced in preparation for another mission. Note the ground crew taking a break on a drop tank, seen under the wing near the main landing gear. NARA/USAAF A17545

P-47s of the 371st Fighter Group, 404th Fighter Squadron, in line for servicing after a mission. Aircraft of the 404th Fighter Squadron wore the fuselage code 9Q. The second aircraft from the right is P-47D-15-RE 42-76172 (fuselage code 9Q-N), flown by 2nd Lt. John E. Bailey. During the afternoon of July 30, 1944, Bailey was flying an armed reconnaissance mission in the vicinity of Pont-Bellanger when his aircraft was singled out by flak batteries. Flight leader Maj. Rodney E. Gunther saw Bailey’s cockpit on fire, then watched as the aircraft fell off to the right and crashed on its back, exploding. NARA/USAAF

P-47D-28-RE 44-20201 (fuselage code 9Q-J) is seen taxiing out for a dive-bombing mission with 500-pound bombs under each wing and antipersonnel cluster bomblets on the center hardpoint.

This aircraft was later written off on April 10, 1945, when it was damaged beyond repair in a ground loop on landing at Eschborn (Y-74), on the outskirts of Frankfurt, Germany. Pilot Lt. Lyman L. Lyons had previously had to put P-47D-28-RE 44-19782 down in a field in bad weather on February 6, 1945, near Chaumont, France. NARA/USAAF 56316-A

Wearing invasion stripes, P-47D-27-RE 42-27376 (fuselage code 9Q-R) of the 371st Fighter Group, 404th Fighter Squadron, taxies out for a dive-bombing mission with a 500-pound bomb on the centerline hardpoint (between the main landing gear). On D-Day, the 404th Fighter Squadron escorted gliders to Sainte-Mère-Église, then dive-bombed and strafed the beaches. Months later, during the drive across France, this aircraft was damaged by flak and crash-landed near Etzling on the French side of the German border near Saarbrücken. NARA/USAAF

Hectic scene at Saint-Pierre-du-Mont (A-1) as Thunderbolts from various squadrons land to refuel and rearm as they strafe and dive-bomb German troops and emplacements in the Normandy area. At left is Lt. Herbert H. Stachler’s P-47D-22-RE 42-26278 (fuselage code A8-Y), Lil Herbie , from the 366th Fighter Group, 391st Fighter Squadron, which was a tenant unit at A-1. Stachler flew two missions on D-Day in Lil Herbie. He survived the war and was separated at the rank of captain. P-47D Lil Herbie was later shot down by an Fw 190 on December 24, 1944, over the Ahrweiler district south of Bonn, Germany, killing pilot 2nd Lt. John K. Jones Jr.

In the distant center of the photo is a Thunderbolt (fuselage code CH) from the 358th Fighter Group’s 365th Fighter Squadron, which, at the time of this photo, was based at USAAF Station 411, RAF High Halden, in Kent, England. At right is a 405th Fighter Group, 509th Fighter Squadron, Thunderbolt (wearing fuselage code G9) that was based at USAAF Station 416, RAF Christchurch, in Dorset, England. NARA/USAAF

The 50th Fighter Group moved to Carentan (A-10), about 9 miles (15 km) south of Utah Beach, on June 25. P-47D-22-RE 42-25904 (fuselage code 2N-U), Lethal Liz II , the mount of 2nd Lt. Arthur Davis, and another 313th Fighter Squadron Thunderbolt wait for the next mission while cows graze in their midst. A number of damaged aircraft line the perimeter of the airfield, with a P-51 Mustang behind the two 313th Fighter Squadron aircraft; an RAF Supermarine Spitfire operated by US Navy Cruiser Scouting Squadron Seven (VCS-7) that suffered a belly landing and a P-47 with a collapsed right main gear can be seen in the distance. Pilots from VCS-7 swapped their usual slow-moving SOC floatplanes for Spitfires to direct naval bombardment against shore targets behind enemy lines. NARA/USAAF 52657AC

A French narrow-gauge railway has been put back into service by members of the 354th Fighter Group. The ore cars carry pilots out to their disbursed aircraft and are also used to carry tools, ammunition, and other service items around the airstrip. The P-51B in the background (wearing fuselage code AJ-S) belongs to the 354th Fighter Group, 356th Fighter Squadron, and is seen at Circqueville (A-2). NARA/ USAAF 53844AC

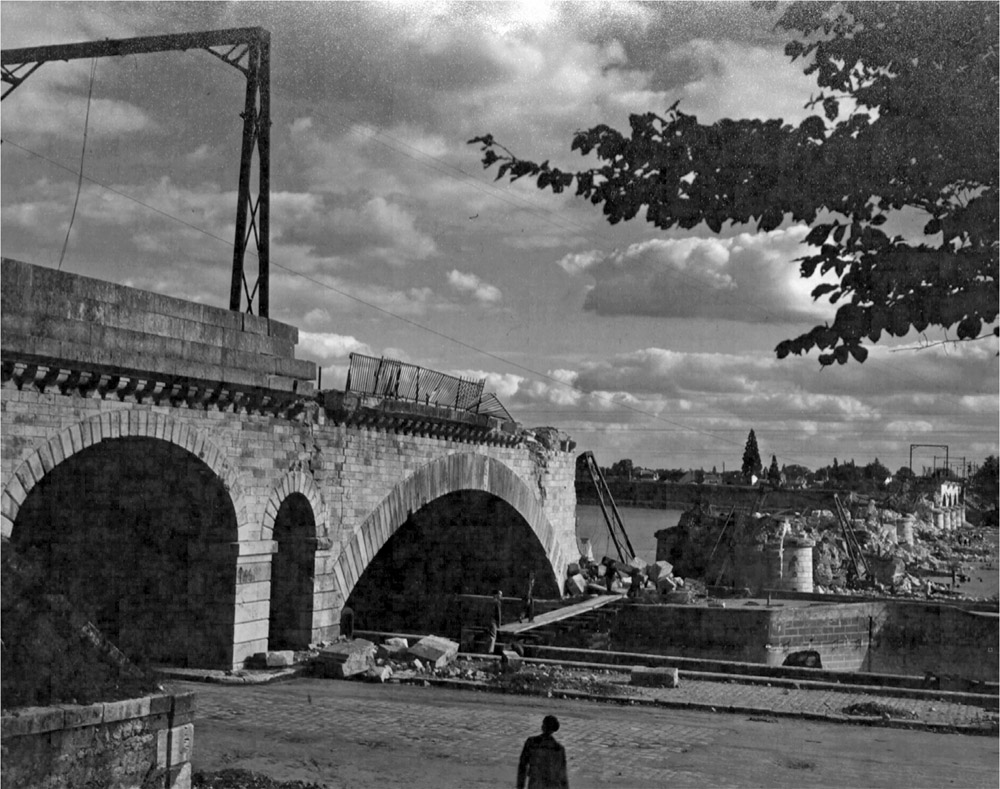

The picturesque stone railroad bridge that crosses the Loire River at the town of Orléans lost ten of its fourteen spans during a June 15 bombing raid. The only human casualty was a sentry patrolling the bridge at the time of the attack. Dropping the bridges prevented the Germans from reinforcing their frontline troops and enabled the Allies to contain the enemy. NARA/USAAF K2786

Deception played a large role during Operation Overlord, on both sides. The Allies had Operation Fortitude, which falsely threatened an invasion force sailing from Scotland to invade Norway, as well as Operation Quicksilver, a cross-Channel landing at Calais. To sell Operation Quicksilver, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton was put in charge of the fictional First US Army Group. Wood-and-fabric tanks and trucks were constructed all over the south of England to give German aerial reconnaissance the impression of a large troop buildup.

Simultaneously, the Germans were employing the same techniques of deception to mislead the Allies as to their strength. Once on French soil, and as Allied troops began capturing Luftwaffe airfields, the extent of the Germans’ use of decoys became evident. Here stacks of former Luftwaffe “aircraft,” complete down to squadron markings on the fuselages, are prepared for the bonfire. NARA/USAAF 52870

A German patrol inspects a Waco CG-4A glider that was slated to land in Drop Zone W as part of Mission Elmira. The glider carried members and equipment of the 82nd Airborne Division. The original caption, in German, implies that the pilot and copilot were killed in the landing and the soldiers inside were taken prisoner. Based on the amount of missing fabric from the nose and fuselage, and the lack of fire, it appears this glider was heavily souvenired by German soldiers. BUNDESARCHIV BILD 146-2004-0176

Ninth Air Force Douglas A-20G-30-DO 43-9502, from the 410th Bomb Group, 644th Bomb Squadron (fuselage code 5D), took off from USAAF Station 154, RAF Gosfield on August 4 to bomb the double roadway bridge across the Seine River at Rouen, France. The target was obscured by clouds, which required the bomber formation to make a second run at the target. By this time German flak gunners had their range, and a photographer in another A-20 caught the destruction of 43-9502. Leaving the target area, the Havoc’s bomb bay doors are open as the flak bursts around the bomber. Moments later the bomb bay doors have been closed as a direct flak hit severs the Havoc’s empennage. The vertical fin can be seen above the aircraft’s left engine as the bomber comes apart. Pilot 1st Lt. Thomas G. Walsh perished when the tailless bomber crashed near Grand-Couronne, south of Rouen. Both gunners, S/Sgt. Fred Herman and Sgt. Karl W. Haeuser, were taken prisoner. NARA/USAAF 53119AC

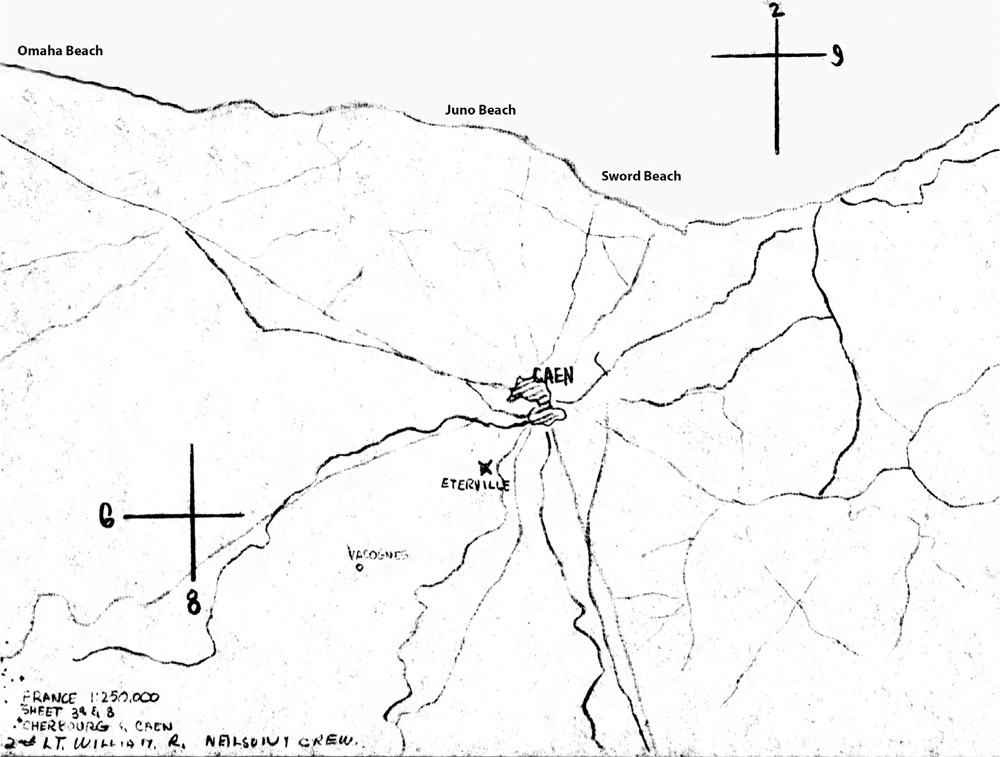

Flying at 11,500 feet en route to bomb road targets on June 13, B-26C 42-107682, Hannibal Hoops , from the 587th Bomb Squadron (fuselage code 5W), 394th Bomb Group, was flying in the formation’s second box, low flight, in the number-three position. Approximately thirty seconds before the bombs were to be dropped on a road junction in the Caen area, flak tore off the port engine and another shell exploded in the cockpit, igniting the forward fuselage. The bomber came down between Étavaux and Eterville, less than 4.5 miles (7 km) from Caen’s town square (see map bottom page 164).

The crew consisted of 2nd Lt. William R. Nielsen, pilot; 2nd Lt. Donald B. Damer, copilot; Sgt. Jack R. King, bombardier; S/Sgt. Adam Toth, engineer-gunner; Sgt. Elmer Fellhauer, radio operator/gunner; and S/Sgt. Gervaise F. Jarmer, tail gunner. Nielsen, Damer, and King in the front of the Marauder perished; Fellhauer, Jarmer, and Toth, stationed in the rear of the bomber, were able to bail out. All three became POWs, with Toth later escaping from a POW work farm and evading recapture. BUNDESARCHIV BILD 101I-299-1819-21A; MAP FROM MACR 6048

Lt. Col. Marshall Cloke (second from right) was the squadron commander of the 354th Fighter Group’s 380th Fighter Squadron. Cloke is seen reviewing mission details with his flight leaders before heading to attack German supply and communications targets. Left to right: Capt. Clayton Kelly Gross (Spokane, Washington), Maj. Gilbert Talbot (Clackamas, Oregon), Cloke (Albuquerque, New Mexico), and Capt. Lewis W. Powers (Compton, California). Gross had five kills to his credit when this photo was taken in late June 1944. He flew 105 missions during two tours with the 355th Fighter Squadron, while Talbot had downed three at this point. Talbot finished the war with five kills, scoring his fourth and fifth victories in March and April 1945 over Bf 109s. NARA/USAAF 56037AC

Maj. Gordon J. Burris (left) interviews Col. George R. Bickell (right) after the first Mustang mission of D-Day. Bickell was a flight commander with the 18th Pursuit Group stationed at Hickam Field, Territory of Hawaii, from 1940 through the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war to 1942. He became commanding officer of the 354th Fighter Group on April 17, 1944, and served in that capacity until February 28, 1945. He was credited with 3.5 aerial victories. Behind Bickell and to the right is ace Capt. Clayton Kelly Gross, who would shoot down a German Me 262 jet fighter on April 14, 1945, for his sixth victory. NARA/USAAF 53433AC

First Lt. John J. Donnelan stands next to his Piper L-4H-PI 43-29676. In civilian use, the L-4 is the J-3 Cub, and numerous examples were pressed into service when the war broke out. The tandem, two-seat L-4 is powered by a 75-horsepower Continental A75-9 flat-four-cylinder engine. These aircraft were perfect artillery-spotter planes and were also used extensively for liaison work, as they could take off and land in short distances from unimproved airstrips. NARA/USAAF 53827AC

A field of Piper L-4s, with 43-30338 in the foreground. The aircraft seen here have recently been removed from shipping crates, assembled, and are ready for test flights. These aircraft had fixed-pitch propellers and were manually started by ground crew hand-spinning the prop. L-4s and their companion Stinson L-5s were known as “The Grasshopper Fleet” due to their small size and green color. NARA/USAAF 53739

Capt. Randall W. Hendricks discusses future targets with a US Army cavalry officer alongside P-47D-21-RA 43-25570, Kwit-Cher-Bitchin (fuselage code D3-H). Note the servicing cart behind the Thunderbolt stacked with 5-gallon jerry cans of aviation gasoline. This photo was taken at the 368th Fighter Group, 397th Fighter Squadron’s first home on the continent at Cardonville (A-3). On June 12, Hendricks shot down four Fw 190s and damaged a fifth 5 miles north of Lisieux (about 25 miles/40 km east of Caen). Ten days later, on June 22, Hendricks shot down a Bf 109 and damaged another, earning him the title of “ace.” NARA/USAAF 80087A

The dangers of strafing trains are evident on the battered leading edge of Lt. Howard A. Spaulding’s 361st Fighter Group, 375th Fighter Squadron, P-51 Mustang. Flying low to score hits on a German train near Chartres, France, he descended too low and struck a tree. Able to maintain flight after impacting the tree, Spaulding managed to return to base. The wing’s missing leading edge looks as though it once held an additional 0.50-caliber machine gun. NARA/USAAF 51977

Hit by flak, his plane’s hydraulics shot out, and seriously wounded, pilot Lt. Jacob C. Blazicek brought his Thunderbolt in for an emergency landing at Cardonville (A-3) on June 17. Blazicek was knocked unconscious when the aircraft nosed-over and came to an abrupt stop. The aircraft, P-47D-20-RE 42-76436 (fuselage code CP-D) from the 358th Fighter Group, 367th Fighter Squadron, was salvaged for parts. Lieutenant Blazicek was hospitalized, eventually recovering from his wounds. Note the heavy flak damage to the port wing, flap, and aileron.

The 816th Engineer Aviation Battalion began work on the advance landing ground at Cardonville on June 7, about twenty-four hours after the invasion began. The airstrip was ready to receive aircraft by June 10, and four days later the P-47 Thunderbolts of the 368th Fighter Group began using A-3 as a forward rearming and refueling base. On June 19, the group moved from RAF Station 485, Greenham Common, England, to A-3, becoming the first fighter group stationed and operational on the European continent. NARA/USAAF 80022AC

P-47 42-76127, Turnip Termite , of the 365th Fighter Group, 387th Fighter Squadron, was the personal mount of Capt. Arlo Henry. Returning from a mission, Henry ran out of fuel and tried to land at A-21C at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Without enough altitude to glide to the airfield, he belly-landed Turnip Termite into a minefield instead. The aircraft was recovered and is seen upon arrival at A-21C, where it was stripped and subsequently scrapped. NARA/USAAF

French pilots of the “Escadrille Lafayette” were equipped with Republic P-47 Thunderbolts to help liberate their home country. The insignia of the Lafayette Escadrille, America’s iconic volunteer squadron that fought alongside the French during World War I before the United States officially entered the conflict, was selected to honor the bravery of the prior conflict’s pilots and the relationship between the two nations. From left, Lieutenants Pierre Chanoine, Jean Honnorat (in cockpit), Henri Ducru, Jacques Maleville, and Jean Marillonnet study a map before strafing and dive-bombing enemy fortifications in the path of Allied armies. NARA/USAAF 56219AC

S/Sgt. Harold Staugler, crew chief, of Fort Recovery, Ohio, works on the landing gear oleo of North American P-51B-15-NA 42-106897, Rigor Mortis III (fuselage code FT-V). The aircraft is seen at Cricqueville Airfield (A-2) behind the invasion beaches. Rigor Mortis III was the personal aircraft of 1st Lt. Edward R. Regis from the 354th Fighter Group, 353rd Fighter Squadron. Regis was credited with three aerial victories, two of which have been recorded on the fuselage under the windscreen. Note how crudely the invasion stripes were applied, especially on the lowered flaps. NARA/USAAF 53860

Soldiers stand by the wing of P-51D-5-NA 44-13309, Fools Paradise IV , as other 363rd Fighter Group Mustangs return to Azeville Airfield (A-7). Fools Paradise IV (fuselage code A9-A) was the personal mount of Maj. Evan McCall. This Mustang flew with the Ninth Air Force, 363rd Fighter Group, 380th Fighter Squadron, and on D-Day the group flew cover for troop transports and gliders as they made their way across the Channel to the drop and landing zones. NARA/USAAF 52356AC

A jeep from the 363rd Fighter Group, 380th Fighter Squadron, wears pinup art on its canvas door cover, used to keep mud from splashing its occupants. The art is Alberto Vargas’s Esquire magazine pinup “Sleepy-Time Gal.” This pinup appeared on aircraft ranging from B-17 and B-24 bombers to a US Navy F4F Wildcat fighter. NARA/ USAAF

Cpl. Carl D. Knox (left) of Syracuse, New York, and Cpl. Alfred Van Drake of Newark, New York, install an aerial camera into an F-6C (photo reconnaissance version of the P-51B). The F-6C could be fitted with two K24 cameras (or one K17 and one K22 camera). Knox is holding a K22 camera, which used a 9 × 9-inch canister of roll film with 200 exposures and was capable of vertical or oblique photography. Note the application of invasion stripes to this aircraft. NARA/USAAF 54734AC

Red nose P-51D of the 4th Fighter Group, 335th Fighter Squadron, carrying 108-gallon paper drop tanks, taxies out at USAAF Station 356, RAF Debden. At the controls of P-51D-5-NA 44-13883 (fuselage code WD-A) is Maj. Pierce W. “Mac” McKennon, who was shot down in this aircraft on August 28, 1944, near Strasbourg, France. McKennon was able to evade capture and return to Allied lines to fly again. McKennon’s aircraft all wore the same fuselage code, and most of the planes he was assigned were named Ridge Runner.

The 4th Fighter Group flew five missions in support of the D-Day landings on June 6, the first taking off at 3:30 a.m. The group paid a high price for its missions that day. A number of patrols were met by superior German forces, and ten pilots from the group did not return. NARA/USAAF

Early-morning wakeup for Ninth Air Force B-26B-15-MA Marauder 41-31606 (fuselage code AN-S) of the 386th Bomb Group, 553rd Bomb Squadron, at Beaumont-sur-Oise Airfield (A-60). The ground crew have opened up the aircraft, and one man is getting ready to remove the cover over the Martin CE-250 gun turret (cylindrical, electric, 2 × 0.50-caliber machine guns) in the aft fuselage. This Marauder was delivered on March 15, 1943, and sent overseas under code Ugly A, departing on May 25, 1943, and arriving to serve with the Eighth Air Force in England three days later. Subsequently transferred to the Ninth Air Force, 41-31606 fought until the end of the war, was placed into storage, and was salvaged on March 14, 1946. NARA/USAAF 56355AC

The first Douglas Havoc in the European Theater to complete 100 missions was A-20G-25-DO 43-9224, Miss Laid. The bomber completed its centennial mission on June 6 and on that day was flown by Lt. Charles L. McGlohn. The aircraft never turned back, due to mechanical problems, and the engines that it arrived with were the ones that powered it over the Normandy beachhead on its hundredth mission. The crew chief responsible for Miss Laid ’s care was T/Sgt. Royal S. Everts.

As the Allied armies pushed across France and toward Germany, a ceremony was held on October 27, 1944, at Le Bourget Airfield outside Paris. In addition to Technical Sergeant Everts, Miss Laid ’s original crew of pilot Capt. Hugh A. Monroe (San Francisco, California) and S/Sgts. Wilmar L. Kidd (turret gunner; Neodesha, Kansas) and Steve Risko (gunner; Chicago, Illinois) were on hand. French actress Madame Monique Rolland rededicated the plane La France Libre to represent the goodwill between the United States and France. NARA/USAAF 54808AC

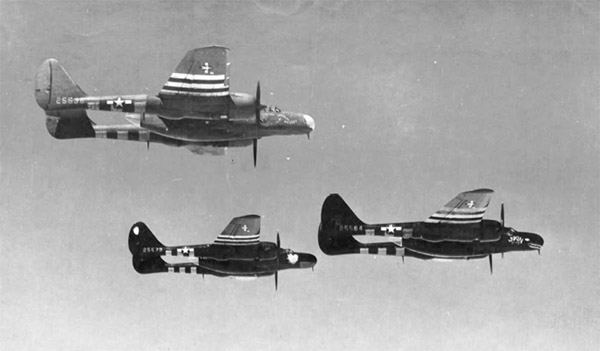

The Northrop P-61 Black Widow was the Army Air Forces’ first purpose-built, radar-equipped night fighter. The Black Widow’s introduction to combat in the European Theater came in the weeks following the D-Day landings. The twin-boom, twin-tail aircraft was powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines. For night fighting, it was fitted with an SCR-720 radar (British nomenclature AI Mk X) that had a 15-mile range under ideal conditions.

Seen in formation are P-61-10-NO 42-5536, Lovely Lady (closest to camera); 42-5573, Husslin’ Hussey (background); and 42-5564, Jukin’ Judy (leading formation). Crews flying Lovely Lady were credited with downing two Ju 88 night intruders in August; by the end of the war, crews flying Husslin’ Hussey had counted four confirmed kills, one probable, and one locomotive; Jukin’ Judy (wearing eyes and a shark mouth) was responsible for downing an Fw 190. NARA/USAAF 53810AC AND 54955AC

Maintainers from the 425th Night Fighter Squadron, Cpl. Arthur Wilitscher of Brooklyn, New York, and Cpl. Roy Challberg of Rockford, Illinois, check the number-two propeller of P-61A-10-NO 42-5576, Sleepy Time Gal. This Black Widow arrived on June 24 and was flown by Capt. Earl W. “Bill” Bierer and radar operator Lt. James Lothrop. The night fighter’s crew chief was Sgt. John W. Birmingham. NARA/USAAF 61362AC

P-61A-10-NO 42-5580, Wabash Cannon-Ball IV , from the 425th Night Fighter Squadron, is prepared for the evening’s flight by crew chief T/Sgt. Neal C. Colbert of Lakeland, Florida (standing outside the aircraft) and mechanic Sgt. E. P. McSwain from York, South Carolina. The fuselage-mounted 20mm cannon are yet to be armed with the belts of ammunition on the ground beneath the aircraft’s belly. The radar operator’s hatch is open at the rear of the fuselage. The aircraft’s name came from the 1936 Roy Acuff recording “Wabash Cannonball.” NARA/USAAF 61362AC

P-61A 42-5569, Tabitha , at Coulommiers, France. The airfield was a Luftwaffe base and was attacked by Eighth Air Force B-17s on June 14 and Ninth Air Force B-26s nine days later. On June 27, P-51 Mustangs strafed the airfield, hoping to destroy the Dornier Do 217N-2 and Messerschmitt Bf 110 night fighters stationed there.

Tabitha crashed on approach to land on October 24, 1944, killing her crew of Lt. Bruce Heflin and radar operator Lt. William B. Broach. NARA/USAAF A49481

A ground crew member inspectsP-61A-10-NO 42-5570, Daisy Mae , before a flight to combat German night fighters. Daisy Mae arrived with the 425th Night Fighter Squadron on June 26 at RAF Scorton. On August 18 the squadron moved to Maupertus Airfield (A-15) near Cherbourg, France. NARA/USAAF K2958

PFC Cornelius Murphy of Hoboken, New Jersey (left) and Sgt. Robert Hendricks of San Francisco load 20mm ammunition into cans that will fly in P-61A-10-NO 42-5583, Dangerous Dan. The 425th Night Fighter Squadron Black Widow was assigned to Pilot Lt. Hugh Byars and radar operator Lt. Bob Brolik. Dangerous Dan ’s crew chief was Sgt. Albert DiLorenzo. In November 1944, while being flown by a different crew, Dangerous Dan was shot down by flak near Saarbrücken, Germany. NARA/ USAAF K2962

The IX Engineer Command followed the initial waves ashore and completed a 3,600-foot dirt strip by 5:53 p.m. on Thursday, June 9. NARA/ USAAF 51793AC

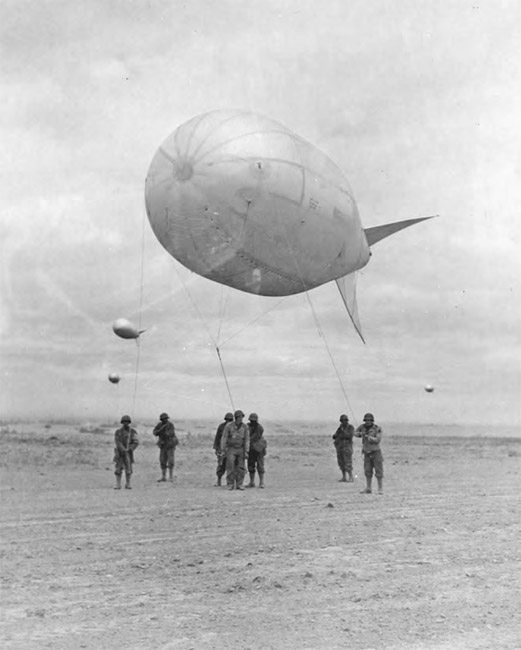

Engineers deploy barrage balloons to help protect troops constructing an advance landing field, most likely Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer (A-21C) based on its proximity to the beaches in the background. The balloon is a British Mark VI kite balloon used to deter low-flying Luftwaffe aircraft from strafing the area. NARA/USAAF 52011AC

Foliage was stripped from the ground, holes filled, and the ground leveled to convert former farmers’ fields into emergency landing strips. NARA/USAAF 55173AC

The IX Engineer Command’s “Dozer Devils” prepare to start construction of an advanced landing field. Bulldozers, graders, DUKWs, and jeeps, seen in the background, were just a small sampling of the kit brought ashore by the engineers. NARA/ USAAF 51667AC

DUKWs, amphibious trucks based on the 2.5-ton General Motors Corporation CCKW (C = 1941, C = conventional cab, K = all-wheel drive, W = dual rear axle) cargo truck, did yeoman duty bringing supplies for the Ninth Air Force to shore. Here a crane removes cargo from a DUKW and will position it in the back of the CCKW at right. The gun ring and 0.50-caliber machine gun, under cover, on the DUKW are noteworthy. NARA/USAAF

Work on A-21C at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer continues as bulldozers and earth scrapers change the former farming fields into a crash-landing strip. This enabled Allied pilots whose aircraft was too badly damaged to land safely rather than risk getting wet trying to cross the English Channel to safety. Here members of the 818th Engineer Aviation Battalion work while soldiers stay vigilant for German snipers. NARA/USAAF 51863AC

A Stinson L-5-VW, 42-99328, has just taxied off the strip at Villacoublay. The strip was open for light aircraft while construction was being completed to accommodate larger aircraft. This field was liberated from the Luftwaffe on August 27, 1944, and immediately the IX Engineer Command’s 818th Engineer Aviation Battalion set to work repairing the field and preparing it for Allied aircraft. The first tenant unit was the P-47–equipped 48th Fighter Group. NARA/USAAF 59202AC

Ninth Air Force Engineers roll out SMT, or square mesh track. SMT was ideal for building runways in a hurry, was lighter to transport than the more commonly seen PSP (pierced steel planking), and greater lengths of SMT could be transported in the same shipping space as PSP. SMT came in rolls 7 feet, 3 inches wide by 77 feet, 3 inches long, with each square 3 inches wide. The roll was unfurled, tacked down, and then the next roll staggered but overlapping the first roll by one or two squares. The overlapped mesh was then clipped together and staked to the ground. Overlapping and clips can be seen on the seam ahead of the road grader. Additional rolls have been delivered to continue the process. NARA/USAAF 52440AC, 51864AC, AND 52511AC

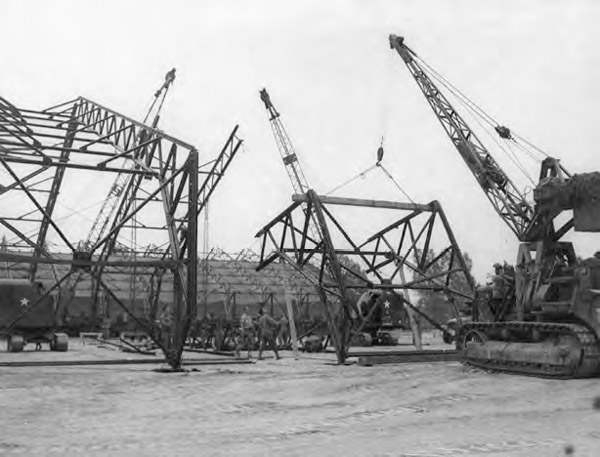

Airfield A-9 was built outside the village of Le Molay-Littry, approximately 7 miles (11 km) west of Bayeux, by the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion. A-9 was operational on July 5, and soon after the F-5 Lightning and F-6 Mustang camera ships of the 10th Photo Reconnaissance Group arrived. Two large hangars were brought over and assembled on the field, making it one of the only airstrips with hangars in the Normandy region. With the battle moving forward at a rapid pace, the Allies did not need to build large hangars, as they were obtained when troops overran former Luftwaffe airfields. The hangar shown here was designed by the Butler Manufacturing Company of Kansas City, Missouri. The steel frames nested together for shipping and were assembled in small subassemblies, then erected in large segments. This model of the Butler hangars went up so fast because the time-consuming task of skinning the building was replaced by thick water-and fireproof canvas. The canvas panels were laced together and then suspended from the steel frame.

Le Molay-Littry (A-9) became an important airfield as General Eisenhower established a forward command post, code name “Shellburst,” at nearby Tournières. NARA/USAAF 76674AC, A-76674AC, AND B-76674AC

When not building airfields, workers in this case a local French contractor were busy repairing bomb holes in runways and taxiways from the previous day’s bombing by the Luftwaffe. Although the Allies had air superiority over the beachhead area, it was not complete, and the Luftwaffe was a force to be reckoned with. A 425th Night Fighter Squadron P-61 Black Widow can be seen running up in the background, while a Cessna UC-78 trainer sits at right. UC-78s were used by night fighter squadrons for base hack and training duties. NARA/USAAF B-61349AC

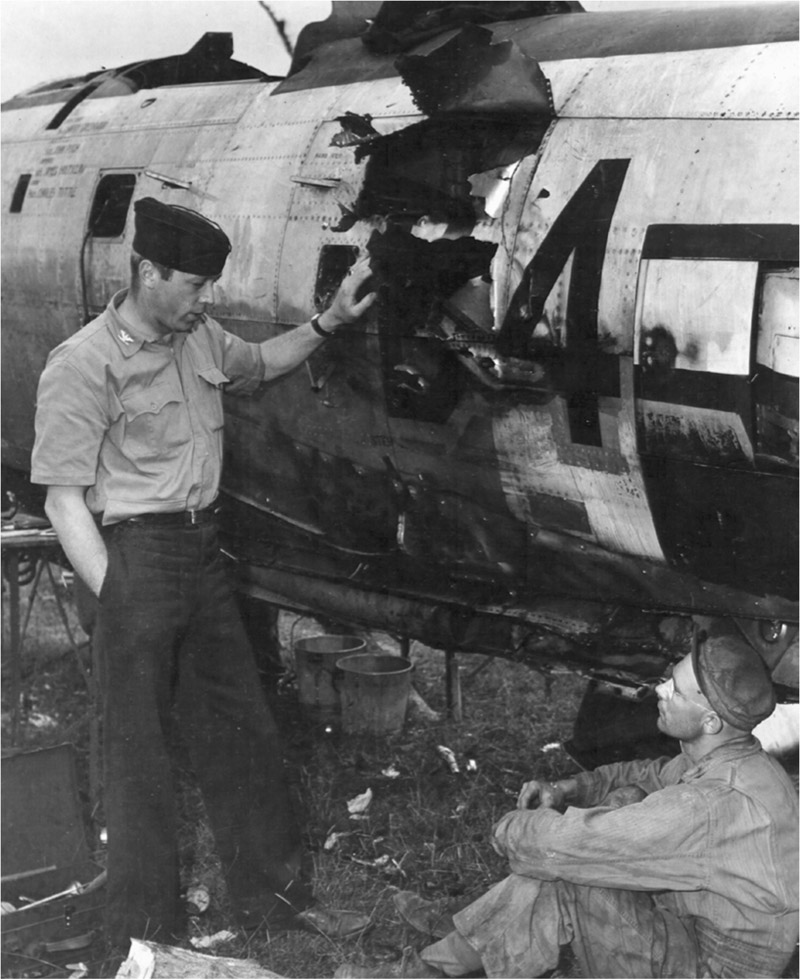

Scratching his head as he realizes how lucky he is to be alive, Maj. Loren W. Herway, commanding officer of the 362nd Fighter Group’s 377th Fighter Squadron, inspects the hole in his Thunderbolt’s fuselage made by an 88mm shell. It was Herway’s 124th mission, and with supercharger and hydraulics, as well as a damaged rudder, he was able to fly the stricken P-47 back to base, where he belly-landed the wreck. NARA/USAAF 56597AC

Col. Ray J. Stecker, commanding officer of the 365th Fighter Group and former West Point All American softball star, and S/ Sgt. Harry Greenwood discuss the fate of a 387th Fighter Squadron (fuselage code B4) Thunderbolt. The P-47 took a direct flak hit at low level but was able to make it back to advanced landing ground A-7 at Azeville. Damaged beyond repair, this Thunderbolt was stripped of useful parts and subsequently scrapped. NARA/USAAF 52853AC

Members of the Ninth Air Force’s Service Command Mobile Reclamation and Repair set up camp for an extended stay working to put this Martin B-26 Marauder back into fighting shape. Mobile Reclamation and Repair units were divided into small detachments, and each was self-sufficient. These units were a tremendous advantage to the Allies in keeping large numbers of aircraft fit for combat. NARA/USAAF 54531AC

Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army received tremendous air support from the Ninth Air Force’s XIX Tactical Air Command, led by Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland (second from left). Inspecting a P-51 Mustang with General Patton (at left) and General Weyland are Col. Homer Sanders (third from left), commander of the XIX Tactical Air Command’s 100th Fighter Wing, and Col. George R. Bickell (at right), commanding officer of the 354th Fighter Group. Gen. Patton was expressing his appreciation to the airmen for their units’ air support. NARA/USAAF 54541

Maintenance area at an advance landing field near the French coast, with a mix of P-47s in various stages of repair and a P-51B in the left foreground. The P-47D in the foreground at right is from the 406th Fighter Group’s 514th Fighter Squadron and wears the fuselage code O7-C. NARA/USAAF 53471

Thunderbolts line an advance landing ground, possibly A-21C at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer based on the lack of trees in the background. The aircraft in the foreground at right is having its eight 0.50-caliber machine guns reloaded as well as some maintenance work done in the engine accessory section. The variety of headgear is of interest—the aircraft maintainers are all wearing baseball-type caps; the GIs on and around the bomb truck sport steel helmets, with one having a knit cap. At left is John F. Thornell Jr’s P-47D-2-RA 42-22474, Pattie . Thornell achieved “Ace” status by June 21, 1944, and amassed a total of 17.25 aerial victories over Bf 109s and Fw 190s as well as a shared credit for an Me 410 before the end of the war. NARA/USAAF

The 367th Fighter Group flew both the P-38 and P-47. On D-Day and the subsequent two days, the 367th flew nine missions. On June 22, Allied aircraft attacked the Germans surrounding the port of Cherbourg with a dozen Ninth Air Force fighter groups. The fighters were to go in low in advance of the medium bombers, and the 367th was the last group over the target. By that time the Germans had found their range. Only eleven aircraft from the 367th Fighter Group returned without damage, and seven pilots were killed during this one mission. Hit by flak during a sortie over German lines, P-38J 42-104144 from the 367th Fighter Group, 392nd Fighter Squadron, was damaged beyond repair and is being stripped of usable parts before being scrapped. NARA/USAAF B-53740AC

Not much remains of this 362nd Fighter Group, 378th Fighter Squadron P-47 (fuselage code G8-G) as maintainers strip the fuselage clean. Notice that the left wing is still attached to the fuselage, providing a main gear, while the right wing has been removed and a jack holds the aircraft up. Ducting for the turbosupercharger can be seen in the background under the tail, while a mechanic is removing items from behind the pilot’s seat. Another is in the cockpit, while an additional pair work in the engine accessory section. Removing parts from a damaged aircraft to keep another fighting is a process that continues to this day, and in the early days of the invasion, before massive supplies made their way from the United States to Britain and on to France, reusing parts from one damaged aircraft was the only source of spares. NARA/USAAF A-53740

Lt. Floyd Mills put his damaged Thunderbolt back on the field, but it was a write-off. The P-47, known as The Mighty Mills , served with the 362nd Fighter Group, 378th Fighter Squadron, and is seen on its belly at A-12, Lignerolles. Enemy troops must be near, as Pvt. Dioniclo D. Johnson, working on the starboard main landing gear, has a steel helmet and M1 carbine close at hand. On the far side of the fuselage, working on the engine mount, is Pvt. Emery Mcfain; in the cockpit is Cpl. Donald F. Condon. NARA/USAAF 11645AC