Chapter Two

Colonial Eyes

Downriver from the hansaray stand the humble premises where Ismail Gasprinsky turned Tercüman into “the most famous newspaper in the entire Muslim world.”1 Over the course of three decades (1883–1914), he exhausted a Skoropechatnik typesetting machine to produce a total of 1,194 issues, each one a labour of love.2 His project was at once sweeping in scope and local in tone, both geopolitically ambitious and intensely personal. Through succinct news capsules and colourful feuilletons, Gasprinsky sought to educate and empower Muslim communities in a clear, straightforward idiom, but he also enlisted them at times in discussions about everyday life in Bağçasaray – about the efficacy of neighborhood policing, for example, or the water quality of the Çürük Suv River.3 For all his designs to command a diverse, international audience across the shores of the Black Sea, he still referred to the newspaper in its very pages as “my” Tercüman and signed off on his editorials and serialized travelogues as simply “Ismail.”4 At times he even devoted entire pages to advertising his trusted Skoropechatnik for the printing of business cards and provincial circulars.5

Today a portmanteau captures the peculiarity of Gasprinsky’s outlook: glocal. The concept of translation at the heart of his periodical’s name was ultimately a translation between the global and the local, a give and take between the universal and the particular. Gasprinsky promoted a pan-Turkism that penetrated deeply into Central Asia while establishing sleepy Bağçasaray as a beacon of a new progressive Muslim culture. At the same time, he tied the prospect of a surge of Russian imperial power and a “heartfelt rapprochement of Russian Muslims with Russia” to the spread of local grassroots education among the Muslim peasantry.6 Centre and periphery were not only radically interdependent for Gasprinsky; they were plural. From his modest printing house in Bağçasaray he reached elites in two mutally antagonistic imperial metropoles – Istanbul and Saint Petersburg – with high-flying visions of thriving empires, integrated populations, and “enlightened” subjects. In one breath he championed the civilizing role of Russia and, of course, called on “Russian Muslims to honour Pushkin.” In another he spoke highly of the regime of Sultan Abdülhamid and lived up to Yurdakul’s praise by publicly embracing the transnational ethnonym Türk rather than Tatar.7 “Although the Turks who were subjects of Russia are called by the name ‘Tatar,’ this is an error and an imputation,” he wrote in 1905. “Those peoples who are called by the Russians as ‘Tatar’ […] are in reality, Turks.”8 In other words, looking upon the destruction of the bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality, Gasprinsky did not attempt to repair or restore it. Instead, in a passionate quest for the socio-political revival of all Muslims in the region of the Black Sea, Gasprinsky heeded his own motto, “What is best for a man is that which is most useful and practical,” and cast Tatar personality into the swell of both pan-Turkism and Russkoe musul’manstvo (Russian Islam).9

At the turn of the twentieth century Gasprinsky therefore cultivated a position for Crimea in both Russian and Ottoman imperial geographies. He serviced Russian and Ottoman claims to the peninsula, which helps explain why Russia and Turkey both attempt to lay claim to his legacy today. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, for instance, opened the proceedings of the 2019 Türk Konseyi (Turk Congress), a critical conduit of Turkish political and cultural power in Central Asia, by citing Gasprinsky as an inspiration behind its integrationist agenda.10 A year earlier a Russian propagandistic documentary film entitled Ismail and His People (Ismail i ego liudi, a title that in Russian studiously avoids ego narod, “his people” in the sense of “his nation”) premiered on Red Square thanks to state support from the History of the Fatherland Fund.11 Even Sergei Aksenov, who is head of the de-facto Russian administration of Crimea and known in the criminal underworld as “Goblin,” refers to Gasprinsky reverently as “our fellow countryman.”12

This transnational appropriation of Gasprinsky today is not only the result of his strategic imperial bet-hedging of over a century ago. It is above all a reflection of the way in which his prolific output and visionary leadership at the helm of Tercüman cleared space for new views that related to but departed from his own. He blazed trails for the diverse, even divergent itineraries that would come well after him. To use Michel Foucault’s vocabulary, Gasprinsky was a “founder of discursivity,” a writer who propelled currents of discourse that he could not anticipate or control, a thinker whose influence spawned respectful rebels as well as loyal epigones.13 Among the former was a motley group of poets and intellectuals who collectively became known as Yaş Tatarlar or Genç Tatarlar, the Young Tatars.

The Young Tatars pivoted away from Gasprinsky to condemn the Russian colonization of Crimea and to fight to secure a singular bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality. In reaction to the decades of rhetorical “de-Tatarization” of Crimea in Russian and Turkish discourse – which, as we saw in chapter 1, accompanied a physical and material one, particularly after the Crimean War – writers like Hasan Çergeyev and Üsein Şâmil Toktargazy pursued a re-Tatarization of the Black Sea peninsula. As we will see, their cultural and political struggle to promote the idea of a bounded territorial Crimean Tatar homeland was not theirs alone. Leading Ukrainian writers at the fin de siècle – Lesia Ukraïnka and Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky – also advanced an anti-colonial discourse invested in the fate of the Crimean Tatar Other. Their remarkably similar approaches offer us a vivid case of intertextual alignment and communion. They also direct us to the role of sight in contesting the dialectic of imperial possession and in returning fire against colonial power. In the process, they make way for something new: solidary reflection, in which the image of the Ukrainian can be seen in the image of the Crimean Tatar.

1.

If Gasprinsky’s vision and leadership facilitated the emergence of voices at odds with his own, the Young Tatar newspaper Vatan Hadimi (Servant of the Homeland; first published in 1906) stood at the vanguard of this opposition. It was Tercüman’s fractious stepchild – vocal, disruptive, and unequivocal in its denunciations of autocracy. “Tsars and sultans offer nothing of value,” its pages read, “other than the gilded crowns on their heads.”14 The newspaper shared Tercüman’s modernizing mission and its goal of unifying Muslims of the Black Sea region, employing a language akin to Gasprinsky’s lisan-ı umumi (common language) to reach the broadest possible readership. But it could not tolerate the deep injustices of colonial rule and, like Gasprinsky, play the long game. In this way Vatan Hadimi was clearly and indelibly marked by the revolutionary fervour of 1905, when the prospect of republican democracy and national liberation in the Russian Empire appeared, if only momentarily, on the horizon.15 The newspaper’s political abandon brought about punitive fines and intermittent closures, all of which reduced its shelf life. Only a handful of its hundreds of issues are extant today. Vatan Hadimi burned brightly but burned fast, ceasing operations in the summer of 1908.

Right before its closure, Vatan Hadimi published a revealing poem by a learned young teacher from Simferopol named Hasan Çergeyev (1879–1946). In a sense, the poem is the newspaper’s epitaph, a poignant reflection on the reason and purpose of its existence. “Your body is broken, your head held high, / Your soul paces in a cage [Canıñ teprene qafeste],” one of its stanzas reads, “But let fear never enter your heart.” Entitled “Közyaş han çeşmesi” (The khan’s fountain of tears), Çergeyev’s work adopts the popular koşma form common to Turkic folk poetry to craft what is at once a lament and an indictment. It bemoans the consequences of the dialectic of imperial possession and does so by communicating with the talismanic literary text that helped empower it in Crimea: Pushkin’s Bakhchisaraiskii fontan, which was translated into the Crimean Tatar language by Osman Akçokraklı in 1899.

If Pushkin may be said to have stolen the legend of Kırım Giray’s fountain for Russian literature, Çergeyev steals it back in “Közyaş han çeşmesi.” As we will see later in this chapter, his short poem would be adapted and recited publicly amid the tumult of 1917 in anticipation of a return of Crimean Tatar political sovereignty. Its political and cultural purchase stems from the way in which Çergeyev reappropriates the image of the khan’s fountain and animates it in a new way. In the elegiac coda of Pushkin’s poem, as we recall, the ruins of Crimean Tatar power provoke the lyrical persona’s pensive reflections on an irretrievable past. Only place remains – a place to be filled, presumably, by imperial colonizers. Pushkin’s persona wanders “among mute passages” (sredi bezmolvnykh perekhodov) of a Bakhchisarai palace enveloped in a pregnant silence: “All is quiet around me” (Krugom vse tikho).

Çergeyev’s lyrical persona in “Közyaş han çeşmesi” finds something more. He too walks the vacant corridors of the hansaray, which he approaches as a site of the past political location and current cultural dislocation of the Crimean Tatars. Wandering its grounds at night, his lyrical persona turns to the fountain of tears and asks it directly, “For whom do you weep?” The fountain answers, “I have been flowing since the times of the khan”:

Evel zaman çeşit sesler

Çuvuldardı bu evlerde,

Şimdi yalnız quşçuqlar

Suv içeler bu kemerde.

………………‥

Boş … xiç bir yerden ses çıqmaz,

Ağlarım, yaş tamlar yere.16

(In days long gone, a host of voices

Whispered in these rooms.

Now only lonely birds

Drink from my basin. […]

Emptiness … there is only silence here,

I weep, my tears falling to the ground.)

The silence in “Közyaş han çeşmesi” is not the silence in the coda of Pushkin’s Bakhchisaraiskii fontan. It is a broken silence. “When I pronounce the word silence,” writes the poet Wisława Szymborska, “I destroy it.”17 Endowed with voice, Çergeyev’s fountain destroys it too. Its voice is dormant agency. In the poem’s concluding couplet, the fountain accordingly speaks of the possibility of a revival of Tatar personality on Crimean place: “I wait for friends to come alive.”

Nearly two decades before Çergeyev, the Ukrainian poet Lesia Ukraïnka (1871–1913) had a similar vision. Stricken with tuberculosis of the bones, Ukraïnka often convalesced in Crimea, where the warmer climate provided comfort. She referred to the peninsula as “the Tatar land.”18 It was a place whose distance from home could provoke feelings of loneliness, but whose complex history and rich cultural inheritance stoked the fire of her talent. Crimean Tatar culture in particular was an object of her artistic fascination and close study. Writing to her uncle Mykhailo Drahomanov in 1891, Ukraïnka reveals that she is collecting Crimean Tatar symbols and embroidery patterns, of which “there are so many good specimens, so similar to Ukrainian ones.”19 As we will see, such similarities between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars were not the only ones she would explore in her work.

Ukraïnka’s letter to Drahomanov was written while she was composing Krymski spohady (Crimean Reminiscences, 1893), a lyric cycle closely modelled on Adam Mickiewicz’s Sonety krymskie (Crimean Sonnets, 1826) and highly intertextual with Pushkin’s Bakhchisaraiskii fontan. Over the course of her career Ukraïnka repeatedly wrote back to Pushkin to skew his wreath of laurels. Her verse drama Kaminnyi hospodar (The Stone Host, 1911), for instance, revisits the Don Juan legend that had been revisited by Pushkin in Kamennyi gost (The Stone Guest, 1830) – her title alone is a knock and a nod – by presenting Donna Anna as an ambitious, calculating tragic heroine and transforming Don Juan into a figure of defiant resistance to conservative power.20 In the second poem of her Krymski spohady cycle, which is entitled “Bakhchysaraiskyi dvorets” (The palace of Bakhchysarai), Ukraïnka gestures toward Pushkin’s footsteps while forging a new path. Her lyrical persona too roams the former seat of power of the Giray khans, but where her Polish and Russian counterparts see only ruins, she perceives faint, dormant life:

Тут водограїв ледве чутна мова, –

Журливо, тихо гомонить вода, –

Немов сльозами, краплями спада;

Себе оплакує оселя ся чудова.21

(Here the fountains barely make a sound,

The water murmurs quietly, mournfully,

And falls like drops of tears;

This special place weeps for itself.)

Ukraïnka’s fountain emotes. As in Çergeyev’s “Közyaş han çeşmesi,” it is invested with agency, intimating that Tatar personality is not a mere vestige of the past but a seed with a future.

Çergeyev does not give an account of the events that wounded the bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality in “Közyaş han çeşmesi.” The wound is simply given. But in a ground-breaking poem written a year later, he offers more detail, surveying the crimes and injustices of Crimea’s colonization through an unconventional lens – the genre of the grotesque. Writing as “Anonymous” (Belgisiz), Çergeyev worked with a private publisher to release the poem “Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!” (Listen to what the dead man says!, 1909) as a twelve-page pamphlet, slim enough to fit inside a jacket pocket. It caused a sensation. Within months of the publication of its Russian translation, the tsarist secret police identified Çergeyev as the author and placed him under surveillance, trailing the “unmarried thirty-year old who lives with his father,” as police reports coldly described him, until his arrest and imprisonment in 1913.22

The “dead man” at the centre of “Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!” is Ümer-oca (Ümer the teacher), a Crimean Tatar from the era of the khanate who rises from the grave and wanders across the Crimea of 1909, only to discover that his homeland, in effect, no longer exists. Crimean place remains, but Tatar personality is nowhere to be found. With satirical flourish Çergeyev adopts the literary genre of the grotesque but turns it upside down. Whereas works of the grotesque typically represent reality estranged by ghosts, monsters, and uncanny Others, “Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!” features a living corpse estranged by the reality of Russian colonization. Ümer-oca is horrified by what he encounters across Crimea:

Yıqıldı köyler, yurt kesildi,

Mezarlıqlar yoq oldı,

Olanın da taşlarından

İlge bina quruldı.

Qaldım, sandım qabaatke.

Quvdılar beni, dediler:

-Poşöl tatarskiy lapatke!23

(Villages were decimated, homes razed,

Cemeteries destroyed,

And from our tombstones

They built country estates.

I fell into the enemy’s trap,

I stayed, thinking I was to blame.

They drove me away, crying,

“Get out, Tatar scum!”)24

In this frightening land of the living, Ümer-oca discovers no traces of living Tatar culture. Only a handful of displaced, dislocated mırza princes remain: “One in a ditch, another in a field, / But none of them knows a homeland [Bilinmez em Vatan yurtu].” He sees only ignorance and poverty, mourning that “Tatar possessions in Crimea [Qırımda tatar mülkü] are only an illusion.” The Crimean Tatars whom he does encounter have lost sight of themselves, having abandoned their distinctive dress and appearance in the throes of imperial-friendly self-fashioning to “look like Ivan.” Ümer-oca’s refrain echoes throughout the poem: “None of you is any different / From the dead lying in the ground.”25 Disturbed by the Crimea of 1909, he proceeds to bury himself back in the grave.

“Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!” lacks the sliver of light of the conclusion of “Közyaş han çeşmesi.” Yet even without a concluding note of optimism, Çergeyev still implies that not all is lost. After all, if the dead can come to life, then the past – once marked by a tight bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality – has a future. “What characterizes a specter,” Derrida reminds us, “is that no one can be sure if by returning it testifies to a living past or a living future.”26 Throughout his verse Çergeyev suggests that Crimea’s “living future” is contingent on scales falling off our eyes, on acts of looking and watching that penetrate the imperial veneer of power and authority. His protagonists preach, as it were, anti-colonial sightedness: his fountain in Bağçasaray “watches” its visitors (insanlara olup seyran) with a studied patience, biding time until there is a Crimean Tatar renaissance and rejuvenation, while his revenant Ümer-oca calls upon his interlocutors – and the reader herself – “to look upon the conditions” (Halımıznı hem baqıñız) around them and demand accountability for all the loss, suffering, and decay.

Here Çergeyev again walked in lockstep with Lesia Ukraïnka. A decade before “Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!,” she also drew attention to the role of sight in the dynamics of the Crimean Tatar encounter with Russian imperial power – but through the perspective of a Ukrainian woman. Her short story “Nad morem” (At the sea, 1901) is a tale of anti-colonial sight-seeing, a journey of intersubjective recognition in which a Ukrainian sees a Russian looking at a Crimean Tatar and, in the process, comes to see herself anew. On holiday in Crimea, Ukraïnka’s nameless first-person narrator bristles at the behaviour of her fellow holidaymakers, whose only desire is to create a simulacrum of the imperial metropole on the Black Sea. She complains that their ships toss “corks, peels, old shoes, and all kinds of human misery” against the shore, while their military orchestras disrupt the tranquility of the natural environment with intrusive horns.27

The plot of “Nad morem” revolves around a relationship – and eventual conflict – between the highly introspective Ukrainian narrator and one of these holidaymakers, a Russian aristocrat from Moscow named Alla Mykhailivna (Mikhailovna), who is drawn to the pretensions of high society. The two spend time together strolling around Yalta’s parks and promenades, but the narrator joins Alla Mykhailivna only reluctantly, unable to decline her invitations with conviction. Ukraïnka casts the Muscovite debutante as a superficial, self-absorbed Francophile who mistreats her servants and falls for a womanizer (sertseïd) who is seeking a casual tryst. Alla Mykhailivna is Chekhov’s Anna Sergeevna without redeeming qualities – or a dog.28

Beneath this relatively banal plot lies not only a study of divergent conceptions of womanhood at the fin de siècle but also an incisive psychological portrait of colonialism on the Black Sea peninsula. The short story turns on a moment in which a Crimean Tatar boy, carrying a bucket of paint in one hand and a large brush in the other, bumps into Alla Mykhailivna and the narrator on the street. Reacting so suddenly that she nearly pushes the narrator off the sidewalk, Alla Mykhailivna screams for the boy to move and insults him under her breath (“muzhlan,” dolt). What transpires is a scene that haunts the narrator:

Хлопець трохи збочив і руку з квачем заложив за спину, щоб не зачепити панну, але при тому кинув такий погляд у наш бік, що мені стало ніяково. Не знаю, чи завважила той погляд Алла Михайлівна і чи вміла вона прочитати в ньому і зрозуміти той страшний, фатальний антагонізм, – темніший, ніж чорні очі молодого робітника. Не знаю, чи й хлопець побачив той погляд, що панна кинула йому вкупі з презирливими словами. Але я бачила обидва погляди, і мені стало страшно – в них була ціла історія.29

(The boy got out of the way and put the hand with the brush behind his back so as not to touch [Alla Mykhailivna], but in doing so, he cast such a gaze at us that I felt ill at ease. I do not know whether Alla Mykhailivna noticed this gaze or whether she could read it and understand that terrible, fatal antagonism – darker than the black eyes of the young worker. I do not know whether the boy noticed the gaze that [Alla Mykhailivna] cast at him or her contemptuous words. But I saw both gazes, and I was horrified – there was an entire history in them.)

Ukraïnka frames this specular confrontation, which underscores the role of sight in the production of cultural difference, as a psychological representation of the colonial relation. Alla Mykhailivna’s gaze is what Frantz Fanon, expanding on Freud’s work on the formation of the gendered subject, identifies as the racial “gaze,” the look of the white colonizer that reifies and fixes the black colonized as dye does a chemical substance (“dans le sens où l’on fixe une preparation par un colorant”).30 For Fanon, the gaze of the colonizer objectifies the colonized and triggers a process of identification through which the latter “recognizes” himself as lacking, deficient, inferior. The gaze of the Crimean Tatar boy, meanwhile, is nothing less than what Homi Bhabha, referring to the work of Fanon, describes as “the threatened return of the look,” a gesture of resistance to this colonial identification that manifests “a potentially conflictual, disturbing force.”31 Ukraïnka’s narrator respects the violent power of this resistance. She envisions Alla Mykhailivna as Little Red Riding Hood chasing butterflies into a forest, oblivious to what happens to the colonizer when “the bloody scarlet of the sky overtakes the forest, the birds grow quiet […] and amid the dark brush, the eyes of the wolf ignite with a wild fire.”32

In this moment, Ukraïnka not only captures the “particular regime of visibility deployed in colonial discourse” but also dramatizes an encounter that exposes the narrator’s identification and solidarity with the Crimean Tatar people.33 For her narrator, this identification is abstract, implicit, and painful: “The boy had long ceased taking notice of us, but I could not stop thinking about his dark gaze [temnyi pohliad], and perhaps because of it, the vacuous affairs and carefree ramblings of my conversation partner evoked in me a kind of oppressive, almost tragic impression.”34 Toward the end of the story, while engaging in a heated argument with Alla Mykhailivna that finally spells the end of their contrived friendship, the narrator feels a building sense of frustration and anger that she cannot control. After impulsively proclaiming to Alla Mykhailivna that their conversations have been vapid and pointless, she remarks in an aside: “I did not say another word. I cast my eyes to the floor because I sensed that I had ‘the dark gaze,’ full of an irrepressible, fatal antagonism.”35 Like the Crimean Tatar boy, the Ukrainian woman harbours an unrealized, deep-seated antipathy to the Muscovite debutante and identifies with the “dark gaze.” Explicit reasons for this identification are never given.

2.

For both Çergeyev and Ukraïnka the anti-colonial struggle is, at its core, a struggle to see and to be seen on one’s own terms. It is to observe patiently, to look through and past the status quo, and to learn to view oneself as an imperial object susceptible to “an irrepressible, fatal antagonism.” In time, as Fanon argues, it is also to realize that one’s own sightlines are shaped by the colonizer, who even in confrontation “determines the centres of resistance” against him.36 Only in shaking free of the imperial gaze can one cast eyes toward the horizons of decolonization and self-determination. Fanon suggests that this step necessarily involves an inward turn, an act of self-affirmation whereby the colonial relation is not merely inverted but discarded altogether. This work is, in Fanon’s words, the work “to make myself known” (me faire connaître).37

For Üsein Şamil Toktargazy (1881–1913), every word was a conduit of such knowledge, every stanza a vehicle to answer the question “Who are the Crimean Tatars?” Born near Bağçasaray in the verdant village of Kökköz, which was the muse of such nineteenth-century landscape artists as Carlo Bossoli and Vladimir Orlovsky, Toktargazy lost his father at an early age. Formal education became an infrequent luxury. While working to provide for his family, he became a passionate autodidact who tried his hand at poems and songs. At first he could not escape Çergeyev’s shadow. His poetic skills were simply not as sophisticated, scholars like Bekir Çoban-zade would later claim; even the foreword to Toktargazy’s debut collection of verse made apologies for his “shortcomings” (eksiklik).38 But what he lacked in finesse, he made up for in force, both poetic and political. As the Ukrainian polymath and Orientalist Ahatanhel Krymsky would argue in 1930, Toktargazy injected the Crimean Tatar national idea with unprecedented creative energy.39

He did so less by litigating the injustices wrought by the imperial dialectic of possession – injustices chronicled in Çergeyev’s “Eşit, mevta ne söyleyür!” – than by promoting, even parading, a renewed equilibrial bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality. His verse not only heaves with exclamatory attestations of this bond but invests it with religious significance. In “Fi-medkh-i-Qırım” (Ode to Crimea), written in the destan ballad form, Toktargazy begins by gesturing to the past panegyrics to Crimean place. “Is there a poet alive who does not love Crimea?” he writes. “The great Pushkin was enchanted by it!”40

Almost dutifully, Toktargazy sings of the majesty of the peninsula’s mountain crags, deep valleys, and cool streams, all of which offer up their beauty and form to Crimea. They do not define it. He ends each strophe with the word Qırıma (to Crimea), using the dative to underscore its position as an indirect object of virtues and affection, as a recipient of felt value. “Love of Crimea [Qırımı hub] is the work of the eternal Allah,” Toktargazy writes, delivering a message of guidance (hadith) attributed to Muhammed:

«Hubb-ül-Vatan minnel iman» hadistir,

Vatanını sevmeyenler habistir,

Bu Vatana Tatar oğlu varistir,

Diğerler sahip olamaz Qırıma!

Qırım kibi Vatan var mı dünyada?

Tatarlıq kibi şan var mı dünyada?41

(The Prophet said, “Love of the homeland is a part of the faith,”

Those who do not love their homelands are sinners,

The heir to this homeland is the son of a Tatar,

Others will not possess Crimea!

Is there another homeland like Crimea in this world?

Is there another honour like Tatarness in this world?)

Toktargazy represents Crimea as the inheritance of the Tatars, and he does not do so casually. He speaks in the language of Islamic law, using varis (warith, “heir”), a term with standing in the elaborate system of regulations of mawarith (inheritance), which is informed, in part, by the fourth sura of the Qu’ran. This is a subtle move, but it is radical. No longer is the Crimean Tatar khan varis, the medium through which Allah bestows the gift of belonging and purpose onto his people. No longer does the khan – or the metonyms (the hansaray and the fountain) continguous with him – embody the bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality. For Toktargazy, this bond now lives through the Crimean Tatar people themselves, who, as heirs, are responsible for its stewardship.

Toktargazy is more teacher than poet here. The hadith he cites– “Hubb-ül-Vatan minnel iman” (Love of the homeland is a part of the faith) – had wide currency among the Young Ottomans and Young Tatars of the era, appearing on the mastheads of Namık Kemal’s Paris-based newspaper Hürriyet (Liberty) and of the Crimean upstart Vatan Hadimi. Its message was efficient. Not only did it bestow religious meaning on the concept of nationalism – communicating, in effect, that being a devout Muslim meant being a patriotic Muslim – but it implied that religious obligations were due to the homeland. Toktargazy was accordingly a frequent practitioner of the obligative mood in the Crimean Tatar language. “We should love Crimea, we should face its losses, / and we should know its strengths,” he writes elsewhere.42

Such prescriptions were only part of Toktargazy’s literary agenda. Like Çergeyev, he had a taste for satire. He reserved his most effective barbs not for local Russian colonizers or authorities in the metropole but for conservative elements of Crimean Tatar society who exploited the imperial system for their own gain. In this way, both Çergeyev and Toktargazy present Crimean Tatar society as internally heterogeneous, captive to competing interests and even conflictual aspirations. In the poem “Para” (Money), for example, Toktargazy sarcastically ventriloquizes the voices of Crimean Tatars who worship wealth and instrumentalize education as a mere tool for material enrichment: “This has become the Tatar way,” he writes. “You learn a trade because / Now it’s all about money, money, money.”43

Toktargazy’s play Mollalar proyekti (The mullahs’ project, 1909) was based on his own experiences campaigning for the poor and working to exorcize the influence of traditionalist clerics in Crimea. It imagines a hasty convention of mullahs debating responses to a campaign on the part of progressive Crimean Tatars – like Toktargazy himself – who travelled to Saint Petersburg to press for more educational opportunities and equality on the peninsula. In the play one of the mullahs reports on the efforts of these progressive activists to reduce the standing of the conservative ulema (body of Muslim religious scholars) and remarks disdainfully, “But who will perform namaz [prayer ritual] for the ignorant Tatar [qara tatarğa]?” After hearing of proposals to redistribute land from the clerics to the poor, the mullah adds, “And what are we going to live on? Should we serve [hızmet etmeq] for free?” Another mullah recommends petitioning the tsar with a drastic proposal: “At the very least we need to write that the Tatar people do not need freedom! Freedom is the tsar’s to give away, so let other people have it!”44

Like Çergeyev with Ukraïnka, Toktargazy had an intertextual companion in the Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky (1864–1913). A Crimean Tatar play like Toktargazy’s Mollalar proyekti is at stake in the novella Pid minaretamy (Under the minarets), which Kotsiubynsky wrote during a summer sojourn in Bakhchysarai in 1904 and published in the journal Kievskaia starina in 1905. The work is a study of a profound generational and ideological conflict between two camps in Crimean Tatar society at the turn of the century, between traditionalist mullahs and progressive, youthful “enlighteners.” With a sustained focus on the lived experience of Crimean Tatars, Pid minaretamy has no room for Ukrainians per se. It makes no explicit mention of their history or culture. Yet as we will see, Kotsiubynsky nonetheless fashions the text as an effective commentary about Ukrainians – and particularly about the debate between narodnytstvo (populism) and modernizm in fin de siècle Ukrainian literature.45

Kotsiubynsky was a pioneer in detaching the Ukrainian language from the representation of Ukrainian life. In his effervescent modernist prose he sets the language free to address universal themes in diverse cultural settings, from Moldavian towns to Crimean Tatar villages. Pid minaretamy sees Kotsiubynsky at the top of his form, combining the flair for impressionistic colour of “Na kameni” (“On the Rock,” 1902) – an akvarel’ (watercolour) set in Crimea and populated with Crimean Tatar, Turkish, and Greek characters – with the kind of extensive ethnographic detail found in Tini zabutykh predkiv (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, 1912). Pid minaretamy is alive with the sights and sounds of Bakhchysarai, with the frenetic rhythms of its cafes and the heated debates of its people. At one point Kotsiubynsky takes us inside a dervish tekke and captures in rapturous prose the young novice Abibula’s synaesthetic experience of sema, the whirling dance:

Плигає тіло в шалених рухах, хвилюють груди, і скаче голова, залита потом, а крізь заплющені очі він бачить небо, усе в огнях. Бачить троянди, червоні гранати, білі лілеї … Горять … цвітуть … літають … Цілий дощ цвітів …46

(His body convulses in frenzied motions, his chest billows, and his head, covered in sweat, dances to and fro. Through closed eyes he sees the sky, consumed in flames. He sees roses, red pomegranates, white lilies … They burn … They bloom … They fly … Flowers like sheets of rain …)

Scattered throughout the novella, meanwhile, are Tatar phrases left untranslated, at once estranging the reader from the text and drawing her into it with a verisimilar simulation of the experience of the foreigner. The shouts of hawkers peddling lemonade in the market bazaar, for example, are “heard” by the reader but not understood: “O-oi buzly! … pek tatly!” (Ice cold! … Quite sweet!)

Kotsiubynsky, in other words, crafts his story through the warp and weft of Crimean place and Tatar personality. Non-Tatar communities are not featured in the text, nor does the politics of colonial expansion figure centrally in its plot. As with Toktargazy’s Mollalar proyekti, what is showcased is an internal struggle for Crimean Tatar personality itself. At the centre of Kotsiubynsky’s novella is Rustem, the son of a prominent local mullah who rebels against a creeping “darkness” and a profound “regress” (vidstalist) that are overtaking the Muslim Tatar community.47 He becomes estranged from his father and, spurning his social station, takes up work at a café run by a family rival. There he agitates against the overbearing influence of local mullahs, imams, and muftis and for the education of women and the poor, calling for enhanced literacy by way of curriculum reform. He discovers an intellectual equal in Mir’iem and dreams of making a life with her out in the wider world, free of the constricting conventions of their patriarchal society. But this dream is interrupted by violent conflict. Disciples of the Bakhchysarai religious elite confront Rustem and condemn him as a sinner and beynamaz (heathen). What ultimately provokes the confrontation is a work of literature, a play like Toktargazy’s Mollalar proyekti.

Rustem is a writer, a character inspired by the likes of Toktargazy, Çergeyev, and other modernizers – or taraqqiparvarlar (lovers of progress) – who emulated Gasprinsky and pursued “knowledge and enlightenment.”48 Such activists oriented their pursuit in the direction of Europe, and so does Rustem. Europe is a beacon for him, a banner to take up. His earnest comrade, the merchant Dziafer, distills this Eurocentrism in a creed: “Give us a literature. Give us our Byrons, our Shakespeares, our Goethes! And then we will stand alongside all other peoples and enter the family of cultured nations! […] A unified, strong literary language, a literature in the European spirit!”

Rustem’s play is written in this European spirit. In a moment focalized through the perspective of the dervish Abibula, Rustem is described as “inciting the people against religion, writing books in which not a word is devoted to God, and mocking old traditions and even the Qu’ran.” After surviving a number of false starts, his play opens in Bakhchysarai to the great curiosity of local tradesmen, workers, merchants, and even clerics, “who wish to see with their own eyes how far Rustem’s courage has taken him.” Kotsiubynsky tells us little about the performance, only revealing that, like Toktargazy’s Mollalar proyekti, it skewers mullahs who misrepresent the spirit of Islam. Kotsiubynsky dwells instead on the play’s reception in the Crimean Tatar community, on the critical reaction that it prompts among local religious elites and traditionalists. They denounce it as “debauchery” (rozpusta).

This scandalized reception of a new work of Crimean Tatar literature, ostensibly prompted by a concern for the moral health and harmony of the people, is strikingly reminiscent of a key moment in the history of Ukrainian culture. In 1902, less than two years before the composition of Pid minaretamy, the Ukrainian populist critic Serhy Yefremov published an infamous essay entitled “U poiskakh novoi krasoty” (In search of new beauty) in the journal Kievskaia starina. Especially outraged by the modernist prose of Olha Kobylianska, Yefremov rails against what he considers a slavish dependence on European thinkers and an elitist contempt for the peasantry on the part of the “young generation” of Ukrainian writers. He labels their literary modernism, with its focus on the psychological world of the individual, a “national pathology” (natsionalnyi marazm).49 His populist offensive against the modernist agenda would prove intensive and prolonged – and influential. Over eight years after the publication of “U poiskakh novoi krasoty,” for instance, Ivan Nechui-Levytsky would revisit the concept of modernist “shamelessness” and argue that it comes dangerously close to “pornography,” in an article entitled “Ukraïnska dekadentshchyna” (Ukrainian decadence).50

Yefremov’s sally in a conflict between narodnytstvo (populism) and modernizm brought about a series of swift responses from Kotsiubynsky. First, he wrote to the primary target of Yefremov’s attack, Olha Kobylianska, with high praise for her talent: “I am simply enchanted by your short story […] Everything about it reveals such a fresh and strong talent […] I am so happy for our literature.” He then expresses regret over the way in which Yefremov and his circle “treat modern directions in literature with such hostility.”51 Months later, Kotsiubynsky wrote Kobylianska again to celebrate her writing: “I am such a sincere admirer of your talent and your completely European style of writing.”52

This positive evaluation of the Europeanness of the new modernist Ukrainian literature is something that Kotsiubynsky would advocate in a public letter written with Mykola Cherniavsky in February 1903. Nominally addressed to Ivan Franko, the document articulated a rationale for a Ukrainian modernist literature in a measured tone: “In recent years the literary movement in Ukraine has become noticeably lively. This is evident both in the increase in literary production and in the growth of publishing activity, as well as in the spread of Ukrainian books not only among the popular masses but also among the intelligentsia […] Our intelligent reader – raised on the better models of modern European literature, which is rich not only in its themes but also in the techniques it employs in the construction of plot – has the right to expect from his native literature a wider field of view, a genuine portrayal of the different sides of the life of all people, not just one layer of society.”53 In Pid minaretamy, written only months after this letter, Kotsiubynsky’s Crimean Tatar hero Rustem echoes this judgment of Europe. In Rustem’s view, Europeans “are stronger than us because their intellect is stronger.” His vocal promotion of European ideals – particularly in literary form – leads to near-fatal physical conflict and the realization that “everyone is against [him].” Rustem considers giving up and leaving Bakhchysarai at the end of the novella, but the support of his friends persuades him to stay and continue the fight.

The congruencies between the Ukrainian populists and the Crimean Tatar traditionalists, on the one hand, and between the Ukrainian modernists and the Crimean Tatar modernizers, on the other, signal a profound identification between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars that is at work under the surface of Kotsiubynsky’s novella. This identification is not a metonymical relation, in which the Crimean Tatar experience stands as somehow a part of the Ukrainian whole. A relation based on such contiguity is the type presumed, for instance, by Ahatanhel Krymsky, the Ukrainian philologist and polymath who claimed Crimean Tatar ancestry.54 Krymsky and his colleagues write that a “complete, multi-sided history of Ukraine is impossible” (usestoronnia, neodnobichna istoriia ukraïnstva nemozhlyva) without a knowledge of “oriental peoples” like the Crimean Tatars, who constitute one “side” among others.55 While Krymsky elsewhere writes of specific parallels between the Ukrainian vertep (puppet theatre) and Crimean Tatar folk drama, for example, he tends to cast such resemblances as partial and particular.56 For Kotsiubynsky in Pid minaretamy and for Ukraïnka in “Nad morem,” by contrast, the identification between the two distinct groups is consistent, thorough, and metaphorical. Their texts are a looking-glass through which the Ukrainian comes to see herself in the Crimean Tatar. In 1917 this dynamic of cultural reflection becomes a political vision.

3.

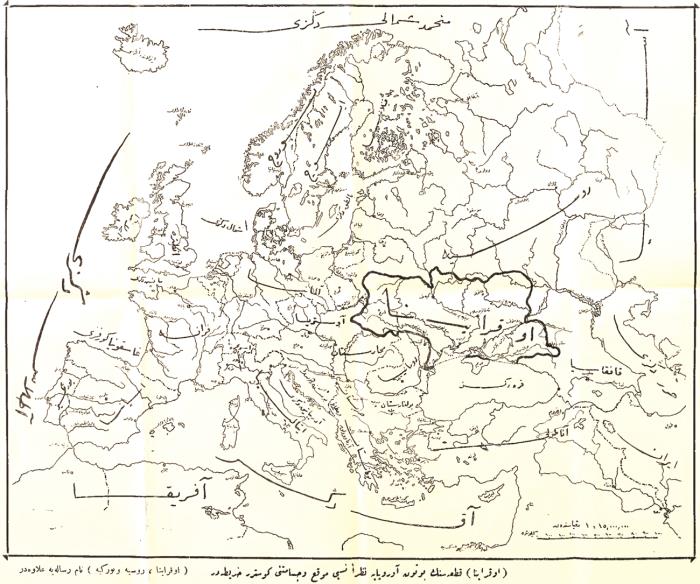

Just over a decade after Kotsiubynsky’s Pid minaretamy, what had been a literary campaign to “re-Tatarize” Crimea – to restore the bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality – suddenly took on urgent political purchase. The chaos of the First World War had blown open political opportunities for the non-Russian nations of the Russian Empire, turning the “national question” into an answer. Across the Black Sea, readers in Istanbul could see the world changing in the very titles of such collections as Ukrayna, Rusya ve Türkiye (1915), which featured a map of Ukraine as a bordered polity not unlike the one we know today, albeit without Crimea (fig. 4). It also featured the eminent historian and political activist Mykhailo Hrushevsky surveying modern Ukrainian history and culture in Ottoman Turkish translation.57 In the popular Istanbul daily newspapers İkdam (Effort) and Tanin (Resonance), Ukraine and Crimea became new geopolitical actors splashed across dramatic headlines.58

4. Map of Ukraine, in Ukrayna, Rusya ve Türkiye (1915)

In the pivotal year of 1917, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar activists had an abiding inclination to support one another in what became a gradual, uneven, and often dangerous climb toward national autonomy. In July, roughly a month after Hrushevsky’s Tsentralna Rada (Central Council) had declared autonomy for Ukraine, a Crimean Tatar delegation visited Kyiv hoping to follow in its footsteps. Among their number was Cafer Seydamet, who considered an “inspection of the Ukrainian national movement [Ukrayna milli hareketi] a necessity.”59 Seydamet and his colleagues asked their Ukrainian counterparts “to support their aspirations for the establishment of Crimea’s autonomy.” More than that – according to the Simferopol-based newspaper Golos Tatar (Voice of the Tatars), “the Muslims expressed a desire for the territorial annexation of Crimea to Ukraine” (o territorialnom prisoedinenii Kryma k Ukrainie).60 Seydamet found a “playful-eyed” Hrushevsky receptive to their cause; Volodymyr Vynnychenko, strangely inscrutable, “off in his own world”; and Symon Petliura, “the sincerest of all.”61

The precise results of these deliberations are not entirely clear. Any record of them has become a casualty of political turbulence.62 What did emerge from the July meeting was a Congress of the Enslaved Peoples of Russia hosted by the Tsentralna Rada in Kyiv in September 1917. On its first day Seydamet paid tribute to the hosts and wished “success to the Ukrainian movement.”63 Symon Petliura replied in turn, “I firmly believe that Russia stands on the brink of death when it does not turn to the living source of the nations that comprise it. All of us – Ukrainians, Tatars, Georgians, and all others – are great nations.”64 Among the Crimean Tatar leaders in attendance was Amet Özenbaşlı, who proclaimed in a passionate speech that, “just as the khans forged unions with Ukrainians […], we free sons of the Tatar people extend our hand to you.”65 He then evoked the legendary image of the fountain in the hansaray, reciting from a Russian-language adaptation of Çergeyev’s “Közyaş han çeşmesi.” Özenbaşlı challenged the attendees of the congress to bring the weeping fountain back to life, to rejuvenate it once more.66

Poems never seemed far from the lips of Crimean Tatar activists at this time. Amid the chaos of revolution, poetry often becomes a harbour of stability and clarity. Some poems were vehicles of effusive apostrophe to national identity: “I do not deny it,” wrote the poet and activist Cemil Kermençikli, “I am a Tatar, a Tatar to my very core!”67 Most were testaments to a renewed bond between Crimean place and Tatar personality. Şevki Bektöre’s “Tatarlığım” (My Tatar identity, or My Tatarness, 1913) – a poem considered “bound to the soul of the nation”68 – refers to this bond in a mode elegiac and prayerful: “My Tatar identity, my homeland [Tatarlığım, tuvğan yerim], / I have loved them both since childhood. / And for them I have often / Wept and suffered.”69

Another poem composed at this time, “Ant etkenmen” (I pledged), would become the national hymn of the Crimean Tatars, a song later sung “in KGB basements and prisons.”70 Its author was Noman Çelebicihan, who joined Özenbaşlı and Seydamet in Kyiv in 1917 and returned to Crimea determined to establish the most progressive parliament in the Muslim world. Named after ancient assemblies of the khanate period, the Qurultay foregrounded the Crimean Tatars as the titular nation of Crimea but sought to represent the interests of all inhabitants of the peninsula, committing to the rights to “freedom of identity [svoboda lichnosti], speech, press, conscience, assembly, housing,” and more.71 Before its first session in December 1917, the incoming members of the Qurultay recited Celebicihan’s “Ant etkenmen” aloud, casting its words across the grounds of the hansaray where Catherine strode triumphantly in 1787.72 Çelebicihan had been appointed mufti, Crimea’s chief religious authority, and his verse accordingly sounds the confident, compassionate tones of the Qu’ran. His lyrical persona also speaks of “living for the sake of” his people, embracing the trope of martyrdom common to the vatan şiirleri of Namık Kemal, whose work Çelebicihan had read voraciously as a student in Istanbul.73 The last stanza of his “Ant etkenmen” looks mortality in the face and speaks of the ultimate sacrifice for his nation:

Ant etkenmen, söz bergenmen millet içün ölmege,

Bilip, körip milletimniñ köz yaşını silmege.

Bilmey, körmey biñ yaşasam, Qurultayga han bolsam,

Kene bir kün mezarcılar kelir meni kommege.74

(I pledged and gave my word to die for the nation,

And knowing and seeing my nation’s tears, to wipe them away.

Even if I live a thousand years, even if I become khan to the Qurultay,

One day the gravediggers will come to bury me all the same.)

Çelebicihan fulfilled this pledge. A recent novella by Uzbek writer Timur Pulatov (aka Timur Pulat) has him write it in his own blood on a prison cell wall.75 In the first months of 1918, Bolshevik forces invaded Crimea, forcing the Qurultay to disband and scatter. They arrested Çelebicihan and took him to Sevastopol’s “Quarantine Bay,” where ships were traditionally held before passengers came ashore. There he was tortured and shot, his clothes and belongings looted, and his body dumped in the Black Sea.76 His murder presaged a new period of violent dispossession at the hands of Soviet power, an era indelibly marked by Stalin’s Crimean atrocity.