THE STEREOTYPE IN PSYCHOLOGY AND THE HUMANITIES

The systems of stereotypes may be … the defenses of our position in society…. No wonder, then, that any disturbance of the stereotypes seems like an attack upon the foundations of the universe.

—WALTER LIPPMANN, PUBLIC OPINION (1922)

The word “stereotype” is used in various theoretical disciplines. Upon closer examination, one finds that the term refers to quite heterogeneous phenomena in each respective field. In one, it signifies prejudiced and socially widespread ideas about foreigners. In another, stereotypes are associated with linguistic formulas that take the form of standardized expressions, and in still others they are considered standardized images and even naturalized recurrent patterns of narration. These kinds of semantic oscillations do not only occur along the dividing lines between disciplines. In many cases, they cut straight across specific discourses. In light of this and the tendency of “stereotype” to convey multifaceted meanings, the theoretical significance of the term and its historical development are worthy of some attention. This not only makes it possible to clarify different concepts of the stereotype, but it also simultaneously delineates a horizon of questions and positions that directly or indirectly shape the discourse on stereotypes in film. Films, after all, are complex phenomena, and as such they can be examined from the perspective of various disciplines. As a result, stereotype concepts from almost all fields have been applied to film and related audiovisual media. One can certainly study films as documents that reflect socially current conceptions about people (Menschenbilder), but one may also—more in the sense of film aesthetics or narratology—analyze stock formulas of images and sound design, or character and plot construction, and so on. The term “stereotype” may be applied in all of these different cases, in each instance with a shift in theoretical perspective, which is not always noticed. An examination of the different theoretical orientations of stereotype concepts promotes an awareness of these shifts and prevents the concepts from simply being lumped together—as the use of one and the same term might suggest. At the same time, this approach also offers the opportunity of a more generalized theoretical and conceptual reflection of “stereotypes,” which may also be of conceptual use for a theoretical approach to film.

CONCEPTS OF THE STEREOTYPE

IN SOCIOPSYCHOLOGICAL DISCOURSE

Social psychology stood out in its ability to claim and circulate the term beyond a narrow circle of experts. Social-psychology studies—or, more generally speaking, those in the social sciences—dealing with the topic of the stereotype number in the thousands. However, a close look reveals that there is no clearly circumscribed, consistent, and generally shared concept even within this field. Given that different conceptual approaches offer quite disparate constructs of what is considered a stereotype, even within social psychology a lack of certainty predominates about the discursive object.

Sociological theories on the stereotype were inspired and strongly influenced by a book on public opinion by the American journalist Walter Lippmann, which was initially published in 1922.1 The term features prominently in the book. Even today there is hardly a relevant work that successfully avoids mentioning this book when proposing a specific use of the expression. Lippmann merely developed very broad ideas and generally investigated the nature of the stereotype in terms of the “pictures in our heads,”2 that is, our thoughts as contributing to “an ordered, more or less consistent picture of the world.”3 However, the concept was soon more narrowly defined: normative ideas, attitudes, or expectations concerning people and used to make judgments about them. This more limited definition still persists in the social sciences today. Studies published in the early 1930s by the American scholars Daniel Katz and Kenneth Braly4 on racial stereotypes proved to be very influential in terms of promoting this more restricted meaning of the term. For their studies, the two psychologists developed their famous attribute-list procedure.

To simplify and without going into the many conceptual differences among adherents to Katz and Braly’s line of research,5 stereotypes are standardized conceptions of people, primarily based on an individual’s belonging to a category (usually race, nation, professional role, social class, or gender) or the possession of characteristic traits symbolizing one of these categories. This concept focuses on belief patterns and emphasizes their guiding influence on attitudes and perceptions.

The different approaches within the social sciences attribute to these belief patterns an entire battery of optional characteristics weighing in differently on individual definitions. Stereotypes are thought to be (1) the relatively permanent mental fixtures of an individual (stability); (2) intersubjectively distributed within certain social formations, for which they assume the functions of consensus building and standardization (conformity); therefore, (3) they do not, or only seldom, rely on personal experience but are primarily socially communicated (second-hand nature); in addition, (4) they are limited to the simple combination of a few characteristics (reduction) and (5) accompanied by strong feelings (affective coloration). Finally, (6) functioning automatically, stereotypes are considered to substantially interfere with the processes of perception and judgment, which they influence and even determine (cliché effect). Regarding the function of stereotypes, the term is therefore generally associated with making judgments, and (7) stereotypes are often ascribed the status of inappropriate judgments (inadequacy).

Katz and Braly also laid the groundwork for this final point—merely by the nature of their experimental setup, which was clearly focused on judgments about people based on individual characteristics. Another contributing factor was their choice of subject matter, that is, their primary interest in negative attitudes toward other races. For the two psychologists a stereotype was therefore a firmly rooted impression of another person, “which conforms very little to the fact it pretends to represent, and results from our defining first and observing second.”6 The theoretical construct thus derived from Katz and Braly was targeted at investigating warped, malicious, and, to an extent, even pathological7 aspects of perceptions and judgments about people. It soon became an established reference for progressive concepts. Stereotypes were largely understood in the manner suggested by the title of a later study: “stereotypes as a substitute for thought.”8

“The masses” were considered particularly susceptible to stereotyping. According to theorists influenced by mass psychology, such as Adam Schaff, the masses seemed to consist of people who spontaneously “do not account for the role of prejudice in behavior. Given that these are the so-called masses, this phenomenon assumes special and often socially threatening significance.”9

It was thought that one could exert a positive influence on the social climate by didactically creating an awareness of the fallacy and irrationality of stereotypes. However, there was a conceptual turnaround in the 1950s, and the work of a number of theorists took on a pragmatic orientation.10 There was a greater inclination to raise questions about the possible benefits of stereotypes—still considered to be stabilized conceptions about people—and to consider their causation. A number of theorists now also emphasized the productive, regulatory functions of stereotypes for cognition, social orientation, and intersubjective behavior—functions that were only to be gained at the expense of deficient representations of reality.

Apart from the continuing thematic focus on the stereotype as conceptions about people, this conceptual shift was more in line with Lippmann’s original intentions. Close in this regard to the philosophy of pragmatism, Lippmann considered the existence of stereotypes, for all intents and purposes, an ambivalent phenomenon. He simultaneously emphasized both the deficient and the functional nature of stereotypes—and argued that they were contingent upon each other. In order to account for this ambivalence he made a number of now classic arguments, which are restated here in some detail, because Lippmann’s extraordinarily influential position is often presented in an oversimplified and sometimes biased manner.

Lippmann’s point of departure and first argument was the functionalism of stereotypes as stabilized cognitive systems of individuals. Citing John Dewey, Lippmann saw the world as “one great, blooming, buzzing confusion”11 that was too complex and dynamic for human perception and cognition. In order for things to take on meaning, he further quotes John Dewey, it is necessary to introduce “(1) definiteness and distinction and (2) consistency or stability of meaning into what is otherwise vague and wavering.”12 Stereotypes thus make a substantial contribution to introducing this kind of definiteness and consistency into the world of perception.

What cognitive psychologists would later address with terms like “cognitive structure” or “cognitive schema” is basically already implicit in Lippmann’s concept. He established the idea of stereotypes as structured mental concepts with a simplifying function, which, as deeply ingrained impressions, are particularly persistent and which guide and even enable perceptive, cognitive, and judgmental processes. On the one hand, they function like symbolic mechanisms. When a trait is recognized and perceived as a core attribute, this data is quickly allocated to a certain preexisting complex of ideas. Thus, “we pick recognizable signs out of the environment. The signs stand for ideas, and these ideas we fill out with our stock of images.”13 Afterward, we see “what our mind is already full of”14 in the thing just categorized. On the other hand, from this perspective stereotypes appear to be a kind of screening filter that provides cognitive relief. They organize one’s necessarily selective gaze, which tends to emphasize everything that repeats itself in similar form and satisfies the stereotype, while other things that do not correspond to the stereotype tend to be played down or even overlooked: “For when a system of stereotypes is well fixed, our attention is called to those facts which support it, and diverted from those which contradict.”15

One can certainly observe the complementary effect, in which discrepancies with firmly entrenched expectation patterns may heighten a sense of difference. Nevertheless, later theorists, for whom the word “stereotype” was synonymous with “prejudice,” primarily referred to the mechanism of blocking out differences.

Although in Lippmann’s work the idea ultimately predominated that stereotypes were to be understood as pragmatic reductions made from a selection of real invariants in the outside world,16 in his thinking about the principles of this kind of reduction he often likened the idea of stereotypes to actively formed subjective constructs, which were always dependent on the disposition and interests of the subject. This becomes particularly apparent when he links his concept—if only in passing—with ideas about objects that are not part of an individual’s immediate realm of experience and that cannot be observed with one’s “own eyes.”17 He considered stereotypical ideas about such phenomena to be constructs based on social projections. In light of actual experience, these constructs always proved to be a kind of pseudoknowledge or at least hazy knowledge.

This is where his second fundamental line of argument comes into play. For Lippmann, stereotypes function as intersubjective systems of integration. Despite their deficits, he believed them to be patterns of cognition coordinated with cognitive or behavioral expectations that society or a group places on the individual. As social “codes,”18 stereotypes are thus subject to cultural “standardization,”19 which they in turn support. As a result, “at the center of each [moral code] there is a pattern of stereotypes about psychology, sociology, and history.”20 As a consequence, stereotypes always also represent instances of intersubjective consensus and social orientation. For Lippmann this was essential to functioning interactions: “In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.”21

Nonetheless, in his view stereotypes are not simply rubber stamps applied from without, but rather they adapt themselves to an individual’s inner disposition, upon which they also exert an influence. They are “loaded with preference, suffused with affection or dislike, attached to fears, lusts, strong wishes, pride, hope.”22

In this context Lippmann ultimately regarded the function of stereotypes as systems for creating and maintaining identity—thus he formulated his third, now classic argument on the value of stereotypes. The degree to which stereotypes are appropriated and habitualized by the individual parallels the extent to which they shape the latter’s personality. Stereotypes thus ultimately become part of an individual’s “defenses”:23 “A pattern of stereotypes … is the guarantee of our self-respect; it is the projection upon the world of our own sense of our own value, our own position and our own rights.”24 Lippmann adds: “There we find the charm of the familiar, the normal, the dependable…. No wonder, then, that any disturbance of the stereotypes seems like an attack upon the foundations of the universe.”25 For this reason, stereotypes are also deeply rooted in the emotions, and their confirmation is experienced as positive.

When one steps back to survey Lippmann’s overall concept, it becomes clear that he did not represent the stereotype as a clearly defined “object.” It is no coincidence that his basic formulations, such as “the pictures in our heads,” operate on the level of metaphor. Hence, at first glance there seem to be valid objections to the hazy and noncoherent aspects of his stereotype concept, which integrates psychosocial functions or processes that are by no means synonymous. These objections, however, miss the point. On the one hand, Lippmann’s outline, with its vividness and diversity, proved de facto to be extremely influential (not only) in psychological research. On the other, it was obviously not his intention to articulate an unambiguous category.

What resulted instead is an open construct—a kind of fuzzy concept—about a complex of interdependent psychic mechanisms. A construct that is ultimately intended to represent a comprehensive epistemological problem: the discrepancy between the “outside world” and the world of perception, thought, and communication—broken down into relatively stable cognitive structures—the very world of the “pictures in our heads” and “our repertory of fixed impressions.”26 Lippmann’s entire theory strives to raise awareness of the highly diverse nature of perception and thought as always culturally or socially constructed—and for the associated discrepancies between mental representation and reality. Figuratively speaking, he funnels the mental fallout from quite heterogeneous processes into a container called the “stereotype.”

Despite its rather diffuse character, Lippmann’s concept is implicitly structured around two inseparably linked motifs of thought, which provide coherency. One is the typological-schematic motif, which initially enables a selective and, in his wording, economic processing of information. The second is the motif of a special stability (habituality and conventionality), through which the results of adaptation processes—quasi-automatic in congealed form—can be reused to produce the already mentioned effects of identity and consensus.

Although he always described stereotypes in terms of cognitive losses or distortions, Lippmann considered stereotypes to be of an ambivalent nature and thus did not just emphasize their deficits in order to lament them. Instead, he sought to give this core dimension of loss and distortion a quite positive accent: it is the necessary price for the capacity of orientation. He basically did not consider perceptions of the outside world and ideas about reality to be conceivable in complete or absolute terms, nor to be void of subjective or cultural predispositions and interests, but always to be context-bound outcomes. Hence, the tendency of distortions or losses did not appear to be a problem, at least as long as the stable “pictures in our heads” functioned sufficiently in a given practical context. Here, Lippmann approximates the basic tenets of modern behavior-oriented cognitive science27 as well as those of John Dewey and William James’s pragmatism, to which he explicitly referred. In principle, Lippmann wanted his stereotypes to be understood as productive variables helping individuals come to terms with their surroundings and stabilizing social behavior. He felt confident that “the abandonment of all stereotypes for a wholly innocent approach to experience would impoverish human life.”28

At the same time, he indicated the problem of the latent tension between the stereotype (as a fixed, context-based form) and shifting contexts, which could lead to errors in judgment. He therefore considered it desirable to have a reflected and flexible relationship to one’s own stock of stereotypes. Flexibility and reflection ensure that the latter are not confused with absolute knowledge. For as soon as we become aware of the relativity of our knowledge as a “loosely woven mesh of ideas,” then “when we use our stereotypes, we tend to know that they are only stereotypes, to hold them lightly, to modify them gladly.”29

While the revision of social psychology’s discourse on stereotypes in the 1950s resulted in a return to Lippmann’s more pragmatic point of view, the semantic scope of the term “stereotype” usually remained limited to the topic of conceptions about people. Since then, there have been ongoing attempts by individual authors to redefine the term and make it consistent or compatible with their predominant theoretical concerns and terminology. This has led in a number of quite different directions. Usually one coherent idea is plucked from Lippmann’s repertoire of arguments, placed in the spotlight, and interpreted or developed on the basis of new theoretical approaches. Precisely because he described more of a syndrome than a category, Lippmann has, in this regard, inspired a complex discourse, which has been continuously updated—and to some extent expanded upon in concentric directions—by the complex of themes, arguments, and intellectual ideas that he largely helped shape.

Below I will discuss two such trends in current social-psychological research on stereotypes—a field today so vast that it is almost impossible to survey.

In Germany around 1960, it was mainly Peter Hofstätter who reemphasized the value of stereotypes in terms of Lippmann’s functionalism. Building on Lippmann’s repertoire, his concept mainly developed the intersubjective integration system and linked it to the traditional focus of the term on conceptions about people. He thus treated stereotypes as notions that remain relatively uniform over time and that are held and communicated by a group about its own members or those belonging to a different group (auto- and heterostereotypes). These ideas appear to be preconceptions,30 since they codetermine individual processes of perception and judgment as preexisting patterns. Like Lippmann, Hofstätter emphasized instances of loss or distortion, which he also justified as the cost of functionality; he was mainly concerned with the functioning of social interactions. The presentation of this argument takes up a remarkably large amount of space, in which he particularly stresses the problem of fictive, “second-hand” notions.

Stereotypes are considered by Hofstätter to be “ideas for which the statistic validity has not been tested, although which we nevertheless nurture with a good degree of certainty.”31 As a rule, they rely on formulaic fictions, which is why the “knowledge that is manifested in a stereotype … deserves little respect in and of itself.”32 As institutions of social consensus and as models for the identity consciousness of a group, stereotypes are nonetheless indispensable, because they do not have “a descriptive but [in a social sense] regulatory function.”33 However, Hofstätter also adds a qualification: “stereotypes of a invidious nature”34 must be combated.

While a main branch of social-psychology research and its stereotype concepts continued (and still continue) to foreground such intersubjective functions, group dynamics, and mechanisms of sociocultural adaptation, another line of research gained influence in the 1980s, which placed more emphasis on intrasubjective topics, namely the cognitive nature of the mental apparatus. Thus, authors such as Tajfel35 or Lilli36 based their concepts on Lippmann’s argument, according to which stereotypes, as cognitive patterns, are considered the necessary result of the human psyche’s limited ability to accommodate the dynamic multiplicity of information.

Lilli in particular sought to explain the process of stereotyping—and its accompanying distortions—as having a single basic psychic cause. The need to create cognitive transparency through the classification of stimuli is inevitably coupled with distortions. These distortions result from the human psyche’s affinity for accentuations: “Facts that contain the same orientational characteristic (label) and that therefore fall into the same class are considered to be more similar than they are (generalization).”37 And: “Facts that contain different “labels” and thus fall into different classes are considered to be more different than they are (dichotimization).”38 The “distortional effects” of generalization and dichotomization are thus systematically manifested in stereotypes or stereotyped perceptions.

Thus, understanding stereotyping primarily as a cognitive function in itself and therefore approaching stereotype theory primarily from the perspective of cognitive psychology—and not, or at least only secondarily, from that of social pragmatism—is an ongoing trend. This is illustrated, for example, by the studies edited by Daniel Bar-Tal et al.39 and particularly those written by the American psychologist Walter Stephan. Whereas Stephan does situate his concept within the traditional social-psychological topic of the image of the other and considers stereotypes to be “cognitions concerning groups,”40 he is nevertheless most interested in how expectations shaped by stereotypes affect cognitive processes. Within the framework of a model he develops—“the model of cognitive information processing”41—stereotypes appear as sets of characteristics associated with defining base categories. Stereotypes can thus be conceived as hierarchically organized mental schemata.

On the one hand, Stephan’s work evinces a proximity to cognitivist approaches based on the problematic premise that significant aspects of human intelligence resemble the operation of a computer.42 On the other, Lippmann’s issue of distortion once again takes center stage: information conforming to stereotypes is emphasized versus the partial suppression of nonconforming data.

This brief overview of these two trends suffices to offer an impression of the range and conceptual diversity of social psychology’s discourse on stereotypes—and also an impression of partial regularities and similarities that constitute this discourse, which shall be addressed again at a later point.

This kind of insight also proves helpful when examining more closely which “stereotype” concepts are pertinent to the analysis of linguistic statements and media texts, including film, because the analysis of media-text content is frequently determined by social psychology’s (or related ethnological) research interests and correspondingly based notions of the stereotype.43

This approach from a disciplinary context suggests itself, given that media reflect the knowledge of the world, ideas, attitudes, and expectations of the individuals that they address. Conversely, the media also plays a substantial role in communicating and distributing corresponding ideas and attitudes—including those which can be understood as “stereotypes” in the sense already described. The latter are concretized by the media in narrative and visual form. Lippmann already pointed this out in regard to film.44 And stereotypes are generally reshaped and modified by media and thereupon serve as the basis for further text production.45 Media texts consequently are interesting documents for social research of a social-psychology bent, which frequently takes the form of a content analysis of film, television, literature, and other media, including language.

A journalistic study by Franz Dröge from the 1960s could be considered a prototype of an approach regarding texts as being primarily documents of the social psyche.46 Dröge clearly sees the concept of the stereotype as logically situated in attitude research. To a great extent his ideas are in line with Hofstätter’s. For Dröge, stereotypes are conceptions about people, groups, nations, and so on—beliefs standardized according to the specific group membership of the individual holding the given notion (autostereotypes and heterostereotypes). He then sought to use content analysis to objectify stereotypes understood in this manner as “coagulated elementary particles”47 within the communicative content of journalistic texts.

To cite a film-related example, a quite similar concept and analytical aim characterizes the study produced at roughly the same time by Peter Pleyer on the reproduction of national stereotypes in popular German feature films.48 Ten years later, the British film scholar Steve Neale also used the term “stereotype” (in pointing out a larger field of similar discourses in his own country) in reference to conceptions about people, which are rooted in everyday consciousness as prejudice.49

Published in the early 1990s, Irmela Schneider’s50 studies on American television series shown on German TV displayed an interest in texts not merely as a reflection and document of prefabricated patterns but emphasized the active role of the media in forming stereotypes. The research that still continues to dominate, however, is concerned with an interest in conceptions about people, which enter the realm of everyday beliefs. Traditional social-psychology themes and content analysis clearly prevail. One the one hand, Schneider’s conceptualization of stereotypes as multipart “hierarchically structured mental schemata”51 is explicitly informed by the cognitive-psychology interpretations of Tajfel and Stephan. On the other, however, articulating stereotypes as “cognitive processes with social consequences,”52 Schneider nevertheless focuses on the capacity of these patterns to foster intersubjective integration. She thus views one of the functions of stereotypes in the reception of television series as semantic: “stereotypes are transindividual constructs of meaning.”53 The recourse to “schemata enabling a stable and invariant attribution of meaning”54 (because largely consensual) limits the receptive semantic variability otherwise characteristic of art. This means a sustained reduction of polysemy.

Schneider explains the main difference between her work and the traditional approach of social psychology in that the latter hardly addresses the medial means through which stereotypes are acquired. Her goal is therefore to analyze the bulk of series on German TV as such an instance of socialization. Specifically she aims to

investigate which recurrent combinations of characteristics can be determined for character types by means of a content analysis of the series, in order to be able to draw conclusions about what kinds of stereotypes may be cultivated by watching these shows. On this basis it is then possible to formulate a hypothesis about what potential consequences this could pose for social behavior.55

Here stereotypes appear as consensual nodes within “common world knowledge.”56

W. J. T. Mitchell also refers to the term “stereotype” in his studies on the emotional appeal of images and pictures in everyday life. He thereby clearly adheres to a sociopsychological understanding in describing the stereotype “as a medium for the classification of other subjects,”57 particularly of “those classes of people who have been the objects of discrimination, victimized by prejudicial images.”58 That means that he is also primarily interested in stereotypes as “bad, false images that prevent us from truly seeing other people.”59 But he is far more realistic than the stereotype critics of the 1970s in emphasizing that “stereotypes are, at a minimum level, a necessary evil, that we could not make sense of or recognize objects or other people without the capacity to form images that allow us to distinguish one thing from another, one person from another, one class of things from another.”60 Not only in this context is he skeptical of the idea of naive enlightenment: “If stereotypes were just powerful, deadly, mistaken images, we could simply ban them, and replace them with benign, politically correct, positive images.… However, this sort of straightforward strategy of critical iconoclasm generally succeeds only in pumping more life and power into the despised image.”61

As the theorist of the “pictorial turn,” Mitchell is naturally also interested in visual concretizations, for example, when Spike Lee “stages the stereotypes quite literally as freestanding, living images—animated puppets, windup toys, dancing dolls.”62 Indicators are not recurring visual patterns but cognitive patterns; that is, he ultimately understands the stereotype as a sociopsychological category: “Stereotypes are not special or exceptional figures but invisible (or semivisible) and ordinary, insinuating themselves into everyday life.… They circulate across sensory registers from the visible to the audible, and they typically conceal themselves as transparent, hyperlegible, inaudible, and invisible cognitive templates of prejudice.”63

Literary studies have also been influenced by social psychology. This is illustrated by works such as Studien zu Klischee, Stereotyp und Vorurteil in englischsprachiger Literatur (Studies on the Cliché, Stereotype, and Prejudice in English Literature) published by Günther Blaicher in the volume Erstarrtes Denken (Frozen Thought).64 Blaicher was interested in “literary stereotyping” as an expression of an author’s prejudices: “a reality formed by prejudices,” the prejudices of the “intended readers,” and the prejudices of the actual readership, which surface in the process of reading.65

Similar objectives—also borrowed from sociology—were pursued in the studies of twentieth-century authors of literature and narrative television formats assembled by Elliot, Pelzer, and Poore in their volume Stereotyp und Vorurteil in der Literatur (Stereotype and Prejudice in Literature).66 There is an interesting semiotic difference made here between the way that fixed, recurrent patterns can function on two distinct levels to inform a text. One is the immediate level, drawing on the discourse of social psychology, of “highly simplistic and therefore implausible characterization(s) of individuals and groups.”67 The second, however, is the (somewhat vaguely outlined) level of noticeable, repetitive language-style patterns that have achieved intertextual/conventional stability. An explanation of the link between these two levels, the “linguistic and stylistic stereotype and socially conditioned prejudice,” is the editors’ stated objective.68

Although here too the concept of the stereotype appears to be associated with patterns on the level of linguistic expression, its roots in social psychology and content analysis still predominate. Given the intention of proving a connection between these two levels, only those recurrent linguistic or, respectively, narrative patterns are deemed “literary stereotypes” that can be interpreted as a “pictorial, linguistic concretization of prejudice.”69 Even if Elliot, Pelzer, and Poore maintained the effectiveness of stereotypes in the spirit of Lippmann’s pragmatic functionalism, their focus on the link between patterns of content/cognition and language/style patterns presented them with a problem similar to that of the linguist Uta Quasthoff. She approached stereotypes from the perspective of linguistic utterances and arrived at the following definition:

A stereotype is the verbal expression of a belief which is directed towards social groups or single persons as members of these groups. This belief is characterized by a high degree of sharedness among a speech community or subgroup of a speech community. The stereotype has the logical form of a judgment, which ascribes or denies certain properties (traits or forms of behavior) to a set of persons in an (logically) unwarrantably simplifying and generalizing way, with an emotionally evaluative tendency. The grammatical unit at the basis of the linguistic description is a sentence.70

In Quasthoff’s work, stereotypes are no longer treated as the actual formulaic notions or judgments applied to groups but as verbal expressions of these socially standardized notions. However, for her this does not affect the obvious grounding of the term in social psychology. In any case, the stable coupling of formulaic language content (convictions about people) and formulaic linguistic form, which Quasthoff more or less takes for granted, cannot be considered valid.

Among the insights provided by semiotics is that one semantic value can be represented by a multiplicity of symbolic forms. In her critique of Quasthoff, Angelika Wenzel determined that “the formulaic nature of stereotypes is only in part applicable to stereotypes,”71 although except for a few varying ideas she largely shares Quasthoff’s ideas about stereotypes.72 Wenzel does, however, make it clear that indicators of stereotypes—that is, stable “formulas”—should be sought not on the level of linguistic expression but in meaning. She considers it necessary to perform “a critical content analysis in order to uncover these stereotypes,”73 because it is not possible “to achieve an operationalization of the concept of the ‘stereotype’ ”74 primarily through linguistic indicators. Even more unequivocally than Quasthoff and others,75 Wenzel thus dispenses with a more narrowly defined linguistic stereotype concept in favor of an investigation into the heterogeneous linguistic representation of stereotypes, which are logically situated in attitude research combined with content analysis.

THE CONCEPT OF THE STEREOTYPE IN LINGUISTICS, LITERATURE, AND ART HISTORY

Based largely on social conceptions about people and corresponding thought patterns expressed in the content of speech and texts, the concepts discussed thus far essentially apply topical issues in social psychology to the fields of film and other media. In addition, there are other concepts of the stereotype primarily focused on standardizations in the form of speech and text, on standardizations of expression. They situate the stereotype indicator on this level and thus clearly break with the logic used in social psychology. Such concepts can be found in theories relating to almost all media, from linguistics to literary theory and art history.

Within the field of linguistics, this different understanding of the stereotype is “naturally” allied with the study of the idiom. This research is not primarily concerned with the question of how the formulas discussed in social psychology are represented linguistically but instead with the way that the medium of language functions within the scope of its own usage. Reusable phrases tend to be flagged as stereotypes. Florian Coulmas discusses stabilized lexeme connections, which are “conventionally used [by a community of speakers] to say certain things and [which] have been learned by the speakers independently of the grammatical rules of the language.”76

Coulmas’ study Routine im Gespräch (Routine in Conversation) discusses this concept as well as related pragmalinguistic research traditions in detail—and works from the idea of a context- and function-based standardization of linguistic expressions: “The similarity of the functional tasks that verbalization must perform in comparable situations renders the invention of new expressions superfluous, and often one can rely on the reserve of one’s communicative experiences, employing one’s memory instead of the imagination.”77

This is how stereotypes develop. What the author means here are fixed collocations, which seem to appear at the very juncture of language usage and the language system. The gradual stabilization of a phrase within language use to the point at which it actually takes on the characteristics of a stereotype, that is, when it has become conventional, can be studied by examples of “when and how events of language use become established on the level of the language system.”78

Proceeding from here, Coulmas emphasizes that stereotypes, integral to the language practices characteristic of a particular group and lifestyle, are dependent on context and situation.79 The analysis of such specific usage requires a “theory of speech situations.”80 In particular, routine formulas—the kinds of verbal stereotypes that Coulmas discusses in depth while only touching on figures of speech, adages, and platitudes—are the result of “situational standardization.”81 “Consolidated in speech, they are organized reactions to social situations,”82 and the exchange of such reactions belongs to the “rituals of everyday life” that “regulate many aspects of everyday interaction.”83 Therefore, such stereotypes do not only operate as functionally adapted fixed forms, but over the course of time they also undergo the linguistic change that accompanies social change. And they also act as reference to the given situational context at the moment of their occurrence. According to Coulmas, the referential nature of stereotypes is much more significant than that of mere lexical items.84

Consequently he argues for a functional theory of meaning, since the semantic content of verbal stereotypes cannot be sufficiently analyzed on the basis of lexical decomposition alone. For Coulmas, this results in specific “problems of connotation, which in this context become prominent as ‘social meaning’ to the same degree that propositional meaning recedes into the background.”85

Coulmas is not alone in his understanding of stereotypes—which is a more narrowly defined linguistic approach than that of Quasthoff and Wenzel.86 French theorists, such as Michael Riffaterre,87 Gérard Genette,88 and Roland Barthes,89 particularly tend to use “stereotype” to denote recurring standardized lexeme connections, without, however, investigating this issue nearly as systematically as Coulmas.

Stereotypes come into play in the writings of Riffaterre when he investigates the function of clichés in literary prose. As a theorist of style, he considers the cliché a special form90 of verbal stereotype (fixed lexeme connections)—and it is a special form that entails a “style factor,” that is, a metaphor that has become conventional. In a pragmatic sense he also interprets the cliché as a functional factor, which carries a crystallized effect. “An effect is therefore, if I may say so, canned.”91

Riffaterre, whose stylistic investigation deliberately introduces the horizon of aesthetic values, generally suspects the stereotype, or cliché, of having undergone a latent loss of meaning. This suspected impoverishment, however, clearly differs from the deficits assumed by social psychologists. It is characteristic of aesthetic-stylistic concerns, and in this context it often dominates thinking about stereotypes. As formulaic, readymade units, stereotypes have naturally been criticized as banal and unoriginal. These aesthetic objections will be elaborated further on. Such reservations were expressed most forcefully by Roland Barthes: “Nausea occurs whenever the liaison of two important words follows of itself.”92

Riffaterre, however, takes pains to present a more nuanced view. He insists: “Even if the cliché is always a stereotype, it is not always banal; one perceives it as such, merely when originality is currently in fashion as an aesthetic criteria; at other times it is categorized as the Gradus ad Parnassum and recommended as ‘pleasant phrase,’ ‘a natural adjective,’ etc.”93

In addition, he also believes—in this regard a functionalist through and through—that even the aesthetic judgment of “banality” does not affect the practical functionality of a cliché; that is, it cannot be truly equated with an inhibited function of the formula, as one ought not “confuse banality with wear.”94 In addition, a differentiation—of consequence for stylistic critique or aesthetic judgments—must be made between two distinct functions of stereotyped phrases in literary texts. Ultimately it makes a difference whether the phrase is presented as (1) “a constitutive element of the author’s writing” or (2) “as an object of expression … as a reality exterior to the author’s writing,”95 for example, in a character’s speech.

While Riffaterre, like Coulmas, places great emphasis on the role of convention in his concept of the stereotype or cliché, for Genette the frequent occurrence of a lexeme connection in the work of an author is apparently sufficient to constitute a stereotype. In his analyses of pastiche and parody he thus uses the term to discuss the multiple appearances of “recurrent phrases”96 such as “rosy-fingered dawn” or “swift-footed Achilles” in Homer’s Iliad, which he considers “self-quotations”97 due to their frequent repetition. Like Coulmas, he also emphasizes how a stereotype functions as a kind of connotative reference to the context in which it appears, in his case the work of an author. Here, the stereotype becomes a “Homerism”: “Each Homeric formula … already forms a class of multiple occurrences whose use by another author, whether epic or not, is no longer a quotation from Homer, or a borrowing from Homer, but rather a true Homerism—the definition of a formulaic style being precisely that nearly all its idioms are iterative.”98 From the point of view of stylistic criticism, Genette does admit that such verbal stereotypes (even in an author’s writing) are potentially appropriate to specific contexts, inasmuch as this pertains to certain types of historical text types like the epic, which introduce a corresponding horizon of values.

When the discussion turns to the analysis and composition of entire texts, the referred-to object of the term “stereotype” once more shifts markedly away from the described linguistic-idiomatic association with conventionally fixed and recurrent word groupings and toward larger structural or stylistic phenomena of literary texts or those in other media.

Here—as in the work of Yuri Lotman—the term primarily surfaces in discussions of the “model-clichés”99 in texts and is used more or less synonymously. However, unlike in linguistics, in this context the term cannot be situated within a specific level or unit. Lotman’s recourse to the word “structure” already indicates that he means constructs tending to exhibit a similar variation in scope and relationship to a textual level as that of “structures.” Admittedly, he is concerned with particular structures, that is, those so deep-seated and familiar to the audience that—as expected patterns within the organization of a text—they can be classified as “cultural codes.”100

Without specifically going into the process, degree, and scope of such codification (one may assume that he means a process of conventionalization), Lotman points out the result: “a frozen system of characters, plots and other structural elements.”101 His examples and frequently used terms like “cliché” also indicate that he is thinking about relatively compact and incisive patterns. In other words, he essentially envisions structures similar to those described by John Cawelti,102 for example, who talks about narrative “formulas” with reference to popular storytelling (in literature as well as other media), or those of Umberto Eco, who reflects on “the iterative schema”103 in mass culture, with which the audience is very familiar.

Given that the pragmalinguist Florian Coulmas examines verbal formulas “conventionally used to say certain things”104 because they fulfill similar functional requirements of verbalization in comparable situations, it would be feasible to develop something analogous to this on the level of conventional textual formulas: a kind of pragmasemiotic concept. This would mean analytically placing stereotypes organizing a text within the context of the functional requirements that gave rise to the context that originally fostered the formation of these stereotypes. For example, stereotypes could be examined as a “canned” response to the widespread desire for emotional involvement (for example, in experiencing suspense) and for identificatory participation, or as a reflection of ideological and mythological needs.

To take this analogy one step further, a functional theory of meaning for stereotypes of textual organization is possible on this basis. Such a concept accentuates the ritual and context-based nature of such patterns and explains phenomena such as the diminishment of propositional meaning and the emergence of referential functions (pointing to original functional contexts). A range of such aspects has in fact been studied in literature and film studies (to be discussed in depth further on) but often without explicit association with the term “stereotype.”

Although Lotman does specifically mention the term, he is not interested—in contrast to a functional, pragmatic position—in the causes and contexts of the functionally determined emergence of stereotypes as textual organization or in the reasons why stereotypes are often readily received. Neither does he address otherwise much-discussed questions concerning the qualities of the formulas, for example, to what extent they are ideological or adequately reflect reality. The possible loss or distortion of content is not an issue for him. Of sole importance to Lotman is the fact that structural clichés exist and, most importantly, that they are preserved as stereotypes in the consciousness of those producing and receiving a text: “Stereotypes (clichés) of consciousness play a great part in the process of cognition and, in a broader sense, in the process of information transfer.”105 Consequently, they function as codes.

In this case, the issue is less the “normal” or simple reproduction of stereotypes and more the manner in which they are referred to when it comes to determining difference. For Lotman, the “intrusion of disorder, entropy or disorganization into the sphere of structure and information”106 is ultimately a process fundamental to the production of specific artistic information and aesthetic quality. The play with the tension between expectations shaped by stereotypes and various actualizations of stereotypes in text is what actually interests him about the question as a whole:

The perception of an artistic text is always a struggle between audience and author…. The audience takes in part of the text and then “finishes” or “constructs” the rest. The author’s next “move” may confirm the guess and make further reading pointless (at least from the perspective of modern aesthetic norms) or it may disprove the guess and require a new construction from the reader.107

Stereotypes are of central importance in this process. However, this is not their primary significance, which instead entails the very establishment of order, consistency, and predictability. Within Lotman’s structural aesthetics, due to the conventionality of these patterns they consequently serve as a common foil for what is ultimately a formal game between the text and the reader, the basis for “artistic systems of this type.”108 Expectations are roused in the reader in reference to stereotypes, and corresponding differences are systematically organized within the text.

But Lotman does not envision absolute difference. In addition to an aesthetics of opposition he postulates an aesthetics of identity. While the aesthetics of opposition evokes the stereotype in the consciousness of the reader by means of the text, only to then destroy it, the aesthetics of identity very much focuses on the deliberate reproduction of salient repetitive patterns at one pole of the text. At the other, however, a wide range of lively material comes into play, which constantly varies the stereotype and combinations thereof. Lotman describes this using the commedia dell’arte as an example: “It is revealing in this sense that commedia dell’arte has, at one pole, a strict set of images and clichés with certain possibilities and certain prohibitions, while at the other pole, it is constructed as the freest sort of improvisation to be found in the history of European theatre.”109

In France, Ruth Amossy developed a literary semiology of the stereotype (with reference also to audiovisual media), which she outlines in her 1991 book Les idées reçues.110 Apart from a number of differences, her semiotic-aesthetic approach has many similarities to that of Lotman. This is already apparent in an early essay from 1984,111 which shall be discussed first.

In this essay, Amossy also emphasizes that all possible structural levels of a text, from the thematic level to that of the characters and narrative macrostructure, can be subject to stereotyping, and she links this issue with a reference to particularly conspicuous stereotyping in mass literature and popular culture overall. In addition, Amossy is also less interested in a pragmatic analysis that attempts to functionally interpret stereotypes as an answer to certain sets of conditions and needs. Like Lotman, she is concerned with the fact, in and of itself, that “recurrent and frozen”112 patterns occur and have therefore become conventional models. Building on this idea, her argument also points toward a tension in the relationship between author/text and recipient: “the stereotype stands at the junction of text and reading. It is necessarily reliant on an aesthetics of reception.”113

Amossy’s aesthetics of reception not only assumes that stereotypes are entrenched “in the reader’s cultural memory”114 and thus can become cognitive factors for reception—and also for the perception of difference—that is, factors that an author must anticipate. Moreover, she envisions an extreme reading strategy that summons the power of the deep-rooted stereotypes as already described by Lippmann: emphasizing stereotype-compliant information and partially repressing noncompliant information. She calls this “stereotyped reading”:115

Reading picks out all the constituents of the description which correspond to the preexisting pattern. In doing this, it trims, prunes, and erases. All nuances which are not immediately relevant are rubbed out. All variants are reduced and reintegrated willy-nilly into the initial isotopism.116

Reading thus recuperates the maximum number of variants and differences while working to reduce them to the Same and Known. Everything that perversely disturbs this harmony of fixed traits reunited in a stable pattern is relegated to the level of “remnants.” For the reader forming the stereotype, these remnants are hardly a problem. Whenever reading does not purely and simply skip them, it … neutralizes the remnants without difficulty.117

Producing distortion and loss, stereotyped reading for Amossy is a process that strives to conform to stabilized stores of belief and knowledge, to tried and true ideas; it is based on excessive pleasure in encountering repetition: “Stereotyped reading allows us to stay on this familiar terrain, where everything has the reassuring form of déjà vu. We have nothing more to learn; we must simply recognize the same in novelty and difference.”118

A text can thus deliberately serve such a reading strategy by confirming the stereotypes it incorporates. However, a text can also resist stereotypes through the creation of difference, that is, by contrasting stock formulas with a “reworking of models and problematization of commonplace visions.”119

Amossy’s essay from 1984 clearly reflects her critical distance to the stereotype and her emphasis on the loss of meaning it incurs (within the context of a clearly representation-oriented position on literature). “For us the stereotype is the point at which repetition becomes routinization, and complexity becomes the most outrageous schematization.”120 Here Amossy indicates that the pleasure found in repetition is solely an aesthetic point of friction—in contrast to her later study from 1991.121 Nevertheless, an argument for a functional approach follows, which in 1984 she understands primarily as the necessity for considering the individual treatment of a stereotype when making an aesthetic judgment about its textual performance. Such judgments must differentiate between the pure confirmation of a stereotype and a contrasting creation of difference. At that earlier point, for Amossy the only appropriate aesthetic use of the cultural patterns was to deconstruct, contrast, and neutralize them and to destroy automatisms. This is obviously analogous to Lotman’s category of the aesthetics of opposition; she favored the logic of this concept.

Within the scope of specific text-based concepts of the stereotype, “text” can be understood in a broad, semiological sense, as art historians such as Ernst Gombrich and Arnold Hauser also use the term “stereotype.” They do so with intentions similar to those of Lotman and Amossy, namely to describe conventionally fixed and recurrent structural patterns of representation. Naturally they are concerned with pictorial representation. Given the visual nature of film, a look at their ideas will conclude this overview.

In the field of linguistic and textual analysis, the stereotype is often coupled with the term “formula,” and Hauser also uses the word “stereotype” to identify formulas—“formal principles”122 (stehende Formeln) of visualization that have developed in the context of the fine arts (though not in isolation from other cultural discourses). Hauser primarily views stereotypes from the standpoint of how communication functions: he considers them as operating within a specific art-historical formation as succinct and conventional schemata of visual composition and thus also as rules for the creation and reception of images. As conventionalized representational patterns shared and accepted by artists and viewers within a given period, stereotypes come close to being cultural codes. Hauser himself uses the metaphor of the “language of art.”123 According to more advanced semiotic terminology, one could also say that he situates his “stereotypes” on the level of specific codes characteristic of different historical periods in the visual arts.

It is interesting that Hauser also addresses the question of a latent loss and distortion through stereotypes. He raises this issue not so much in terms of the ability of an image to accurately represent external reality, that is, in terms of content, but more in relation to the aesthetic problem of how to achieve individual expression by conventional means. Hauser’s argument is consequently based on an “aesthetics of identity” with functional tendencies. Communication is only comprehensible “when it submits to schematization and conventionalization and … moves from the sphere of private and personal meaning into that of interpersonal relationships.”124 This “always has to pay the price of the content which is to be communicated losing part of its original sense.”125 One must deal with this creatively, as he rightly adds, since it is pure fantasy to think that one can ignore this fundamental relationship: “Completely subjective and spontaneous experience free from each and every conventional and stereotypical element is a just a borderline concept, an abstract idea which bears no relation to reality.”126 Therefore, one should not always consider an affinity to stereotypes a “deficit” but rather a condition of artistic creativity:

The process is dialectical. Spontaneity and resistance, invention and convention: dynamic impulses born of experience break down or expand forms, and fixed, inert and stable forms condition, obstruct, and enhance each other…. Artistic expression comes about not in spite of but thanks to the resistance which convention offers to it…. This is a striking example of Hegel’s Aufhebung: a simultaneous erection and destruction of valid conventions, symbols, schemata.127

In an obvious parallel to Riffaterre or to Lotman’s example of the commedia dell’arte, Hauser then also refers to cultures that have an entirely different level of acceptance for schematization, repetition, and conventionality than is permitted by modernity’s aesthetics. Hence, for example, in traditional East Asian culture the direct reliance on repeating visual formulas, which are substantially reduced in complexity, is considered a sign of “abstract, strictly formal art” and is thus also considered to be “more refined.”128

From this perspective, he thus views the conflict-ridden interplay of stereotypical and spontaneous, individual tendencies as an essential characteristic of the entire history of art—surfacing in different contexts and manners, placing highly varying emphases on the opposing poles of stereotype and difference, and resulting in very heterogeneous solutions. The play between stereotype-generated expectation and difference, which Lotman describes in a temporal dimension, is now quasi applied to the surface of the image. In Hauser’s writings, the concept of the stereotype is most strongly evident in works or epochs in which simple, reduced, and conventional visual formulas tend to quite obviously dominate the concrete image in the sense of a “stereotyped style”129 and in which this occurs in numerous similar cases; that is, formulas become conventional and stylistically definitive, as in the “stereotyping of art” in Egypt.130

Ernst Gombrich’s use of the term “stereotype” has similar implications.131 He also emphasized that pictorial representations of the visible world are mediated through a system of schemata in the mind of the individual artist. He too associates this with the metaphor of “the language of art”: “Everything points to the conclusion that the phrase ‘the language of art’ is more than a loose metaphor, that even to describe the visible world in images we need a developed system of schemata.”132

Considering this “system of schemata” or “mental set,”133 Gombrich’s argument (aimed at examining the inner processes that dictate an artist’s activities) is more firmly rooted in cognitive psychology than Hauser’s, which is dominated by semiotic-communicative functionalism. For Gombrich, an internal system of schemata guides artists’ views of external reality as well as their creative activities. Stereotypes play a special role in this process. Repeatedly using the words “pattern” and “formula,” Gombrich makes it clear that he understands stereotypes as particularly stable schemata of visual or artistic representation, which can be considered conventional within a given art-historical formation. The individual artist receives them and internalizes them as “second-hand” formulas.134 In other words, different from a more idiosyncratic schema characteristic of a single artist’s work (personal style), the stereotype is viewed by Gombrich as a firmly entrenched conventional schema.

It is worth noting that, above and beyond his cognitivistic approach, he also links the topic of the stereotype with a functional argument, namely the idea of the readymade effect. While Riffaterre, with respect to literature, talks about stylistic formulas that quasi store specific effects, Gombrich refers to visual stereotypes, which have each been specifically developed to produce a unique affective impact. In this context he introduces Aby Warburg’s concept of the Pathosformel (pathos formula).135

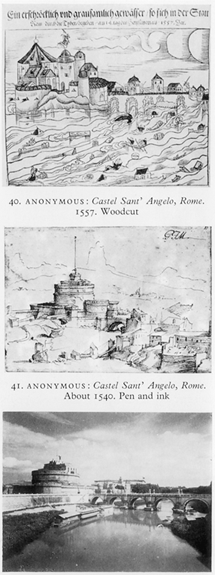

However, also for Gombrich the stereotype is linked with a latent problem of loss or distortion, which is primarily manifested in the tension between his stereotypes and the valid visual representation of reality. The latter is one of the claims of art and a primary concern in Art and Illusion. He dedicates an entire chapter to an exhaustive series of examples demonstrating the deficits of stereotypes in the pictorial representation of reality. The problem is made clear from the start by the chapter’s title, “Truth and the Stereotype.” For example, in this section of the book he outlines how convention predominates over mimesis in visual representation throughout the history of German art. Thus the fixed idea of how a castle should look was imposed on graphic depictions of the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome, which in reality has a quite different appearance. Lippman’s statements about the formative power of stereotypes come to mind once again, when one reads Gombrich’s explanation of how stereotype and real appearance enter into a strange symbiosis in the woodcut he analyses.136 This is not just a matter of polemics, for Gombrich dedicates substantial space to presenting a nuanced argument.

This reference to stereotypes is not only necessary in the sense that they help transport an artistic “language”—that is, in the sense of symbolic systems of depiction and information. For Gombrich they have even more significance as stabilized cognitive systems for the visual processing of the external world: “Without some starting point, some initial schema, we could never get hold of the flux of experience.”137

Highly significant to Gombrich is the explicit differentiation between the stereotype as a specific schema in the mind of the artist, or in pattern books, and the manner in which is it realized—which he describes as “adaptation”138—in the process of the actual production of a work of art. Thus, for example, he differentiates between the varying degrees and ways in which images are formed by stereotypes. On the one hand, he describes cases in which representation is strictly governed by a stereotype based on a simple and highly reduced schema (as in postclassical Greek art): “The schema was not criticized or corrected, and so it followed the natural pull toward the minimum stereotype, the ‘gingerbread figure’ of peasant art.”139 On the other, he also refers to the possibility of a distinctly more flexible adaptation of the stereotype in more sophisticated images: “Once we pay attention to this principle of the adapted stereotype, we also find it where we would be less likely to expect it: that is, within the idiom of illustrations, which look much more flexible.”140

FIGURE 2 Stereotypization of visual representation: views of the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome. A series of images from E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (1977), 61. Anonymous woodcut, 1557 (above); anonymous drawing, pen and ink, circa 1540 (center); modern photograph (below).

Again the idea is expressed that one should have a ready willingness to correct one’s own stereotypes—in this case, conventional pictorial formulas. As “starting points” in the reciprocal process of perception and creation, stereotypes are seen as necessary and acceptable, given that they are subjected to a “corrective test” and are creatively adapted over the course of the artistic process.141

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE CONCEPTS/FOUR FACETS

Given the (highly complex) topic at hand, this overview of stereotype concepts in the social sciences and humanities is by no means exhaustive, although quite comprehensive. Following the principle of pars pro toto, it nevertheless does reveal trends in the conceptualization of the term, which may also ground the analysis of the discourse in relation to film.

Thus far it has been demonstrated that the theoretical use of the term “stereotype” and its corresponding concepts can neither be attributed to a single discipline or method (for example, limited to social psychology, as often claimed) nor to a clearly defined object of investigation, such as conceptions of people. The assertions as to what constitutes a stereotype and on which levels of theory it is situated are too diverse, even within individual disciplines. Over the course of this overview, however, it has been possible to delineate three fundamentally different kinds of fixed formulas or patterns, which are considered stereotypes within the individual discourses. Discussed so far in the context of the social sciences were (1) thought and attitude patterns pertaining to social phenomena, in particular formulaic notions concerning members of social or ethnic groups. Next, (2) linguistic forms in the sense of conventional lexeme connections, that is, routine verbal formulas, were addressed within the scope of the idiom. Finally, (3) we looked at the patterns or “formulas” that shape the structure of entire texts or segments of texts, whether within literature, the fine arts, or any other kind of text.

If there is a common element at least virtually shared among the various concepts of “stereotype,” then it must be sought in a tendency that links activities such as perception, cognition, and communication with their material results (texts). This can only be described in very broad terms. However, a common link could be most appropriately articulated as follows: in all these interdependent spheres, more complex, composite142 forms, structures, or patterns evolve, which are then repeatedly reproduced en bloc in similar or similarly perceived functional contexts and therefore tend to be very persistent.

It stands to reason that this smallest common denominator is closely related to the etymology of the word, which stems from printing technology. It is based on the compound of the Greek words τύποσ, which can be translated as “impression,” “figure,” or “type,” and στερεόσ, which in this context means “solid.”143 Within the field of printing, the compound word was used to describe a printing plate cast in one piece, in contrast to composite plates with moveable letters. The stereotype thus unites multiple characters or lines of print in solid form. The term retained the meaning of a stable form composed from multiple elements, which could be printed (reproduced) repeatedly, when it was carried over into more general usage as a metaphor in the nineteenth century. Scientific and scholarly terminology was later based on this common usage of the word.

In and of itself, this smallest common denominator appears to be rather insubstantial. It also seems too abstract to serve as the sole foundation for an outline of fundamental discourses on stereotypes in film or for a definition of terms appropriate to the analysis of film. It is certainly equally important to develop a keen sense for the kinds of heterogeneous theoretical contexts in which the term is used: theoretical perspectives that—although leading to various “objects of investigation” and concepts—have almost all been applied to film or at least can be developed in regard to phenomena within this medium.

This approach has one very obvious implication: in regards to film or cinema (understood as film culture in general), it makes little sense to try to find a master concept, such as the film stereotype, to serve as an alloy of all the discursive statements associated with the term “stereotype.” Here too, one must always consider the theoretical locus of any given conception of the term. From this vantage point, the very differences between the concepts discussed so far can actually offer a more precise perspective. Also, despite all the differences in the various fields of study and theoretical approaches, it is possible to identify a good number of regularities, relationships, and similarities. While these are by no means consistently articulated in each concept, as a whole they could be said to belong to a kind of family of statements, cognitive motifs, and arguments. “Family” refers to Wittgenstein’s famous reflections on the “game.” In light of the great variation in types of games, the latter term does not denote an absolute set of shared traits but a set of “family resemblances”: “We see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: similarities in the large and in the small…. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than ‘family resemblances’; for the various resemblances between members of a family … overlap and criss-cross in the same way.”144

This explains why “stereotype,” as a discursive entity, seems much more compact and fulsome—due to the interplay of its individual facets (its family resemblances), which are understood as clusters of similar arguments—than the paltry framework of the smallest common denominator would make it appear. This framework, in contrast to Wittgenstein’s “game,” does at least seem possible in this context.

The next step is to outline four such facets:145 (1) schema, reductionism, and stability; (2) automatism and conventionalization; (3) distortion and loss; and (4) a ground for difference to emerge. In the process of fleshing out these theoretical facets, differences between them will be examined and related to methodological considerations. The resulting “theoretical web” will then be used as an orientation for the analysis of various approaches, emphases, and questions within the film-related discourse on the stereotype. On this basis it will then be possible subsequently to include statements about film that do not explicitly use the key word “stereotype” and instead operate with terms such as “pattern,” “schema,” “cliché,” and so on, whose meanings, however, correspond to the outlined repertoire of facets in the discourse on stereotypes.

FIRST FACET: SCHEMA, REDUCTIONISM, AND STABILITY

Regardless whether one is speaking of “formulas” or “patterns,” stereotype concepts are often associated with ideas and statements that are also constitutive of the term “schema.” It is not uncommon for stereotypes to be explicitly described as particular schemata—whether the term refers to thought patterns about external reality or to patterns in the organization of text or textual segments. This is reflected in the cognitive psychology approaches of Lilli and Stephan and also those of Gombrich and Schneider. Only in the description of verbal stereotypes does the term “schema” fail to play a role.

The reference to schemata seems plausible, given that the various stereotype concepts refer to phenomena that manifest solely on the level of comparison with an individual idea or concrete textual segment, a comparison giving rise to abstractions. Similar to the way that schemata are formed, the analytical perception of a stereotype always necessitates the suppression of concrete information. This kind of perception is always oriented toward reduction, simplification, and the pattern-like. In other words, stereotypes, just like schemata, do not consist of complete passages of text or images, and they hardly consist of fully formed ideas (only the readymade formulas of verbal stereotypes could in this case be considered an exception to the rule of “incompletion”). Stereotypes are virtual entities that become viable only through comparison and abstraction. The perception and understanding of stereotypes as stereotypes requires a special mental effort of construction. Conversely, the actualization, reproduction, performance, or—in Hegelian terms—“sublation” (Aufhebung) of stereotypes, and also of schemata, does not yield the identical but the similar.

Meanwhile, it is usually the element of reduced complexity, inherent to every schema, which most insistently stresses the notion of a stereotype—as soon as this reduction becomes clearly noticeable through specific textual performance, that is, when it concretely generates conspicuous simplicity. It is no coincidence that the art historians mentioned here for the most part associated the word “stereotype” with images that were often dominated by recurrent and simple forms or “formulas”—images whose actual composition is reduced to a minimal stereotype (Gombrich) displayed as a “ ‘gingerbread figure’ of peasant art” or images, as in Egyptian art, that tend to exhibit a “stereotyped style” (Hauser). Also, in regard to literature, Ruth Amossy considered one of the “golden rules of stereotyping” to be the coupling of “the poverty of its constituents” with formal consistency (homogeneity) and redundancy.146

If from a cognitive point of view the stereotype, as a recurrent form of abstraction, approximates the concept of the schema, then it is necessary to defend the “schema” against a common and problematic (mis)understanding of the term. A mechanistic interpretation is often forced upon the term, because “schema” features prominently in a branch of cognitivism, which views human perception as a sort of rational machine and which is based on an ideal of perception as an objective, correct representation of an external world independent of a perceiving subject. In this context, the notion of schemata comes close to rigid matrix models, as a stable representation of a logical synthesis of invariants in the external world. This does not do justice to the living psychic processes occurring in discursive reality. This particularly applies to nonformalized everyday thought and communication, which tend to follow “the approximate, ‘fuzzy’ logic” of practice articulated by Bourdieu147 and are certainly relevant to the question of the stereotype.

However, the term “schema” per se should not be discarded together with its logocentric interpretation. Even alternative constructivistic approaches opposing hardcore cognitivism retain the basic idea of schemata. This is true of Varela’s behavioral approach to cognition, whose idea of “structural coupling”148 seems the most plausible. Varela conceives of perceptive and cognitive schemata that guide everyday thinking as autopoietic constructs of human experiential reality and not mere representations of apparent similarities of a purely objective external world. As the former, they bear the obvious traits (of intersubjectively and socially mediated) subjective constructs and are capable of linking cognitive, affective, and associative factors of active consciousness.149

This preserves the most important idea regarding cognitive schemata, which Luhmann formulates as follows: “it is a question of forms which, in the ceaseless temporal flow of autopoesis, enable recursions, retrospective reference to the familiar, and repetition of operations which actualize it.”150 They thus appear as operations of the memory, which—although they cannot be defined as rigid patterns—do correspond to repetitions or accumulations of similarities. They also function as forms that reduce complexity and introduce relative stability and consistency into our cognition, communication, and practical behavior. Simultaneously they have the quality of rules, in order to facilitate quick responses.151 Moreover, schemata, as constituted by everyday consciousness, are not to be viewed as isolated, one-dimensional constructs but instead as organized in emergent networks of memory.152 That means that they interact comprehensively, which is what enables actualizations of schemata often to become processes of interdependent associations and symbioses.

Given this understanding of the schema, it makes sense to examine the concept of the stereotype accordingly. A good number of stereotype concepts emphasize that stereotypes, like schemata, do not simply register repetitive elements of the represented, concrete world but rather integrate analogous behavioral and situational contexts. This argument is especially favored by pragmatic and functionalist approaches. If one includes communicative activity in the definition of behavior, then both schemata and stereotypes can be interpreted as behavior-related entities, which, as Coulmas illustrated with verbal stereotypes, have developed in the context of different behavioral exigencies and types of situations. This means that stereotypes do not only function as representational patterns of external reality. A good number of stereotypes can individually be considered a “formula” for meeting a typical behavioral requirement, as a proven structure for mastering a specific (communicative) situation or task.

This in itself implies that stereotypes as well as schemata by no means function solely as a means of rational orientation. As formulas of thought and conception, they have a holistic and therefore also emotional function. The idea that stereotypes are linked with the emotions appears to be a key feature of many theories. In a number of cases, stereotypes, as specific schemata of communication and textual organization, can even be interpreted as differentiated functional forms that ensure the activation of affective responses (as intended in aesthetic fictions) in the addressee. Consequently, they can be interpreted as pragmatic entities, which are coordinated with behavioral (and also communicative) contexts and which have gradually adapted themselves to specific contexts—such as the dispositions of the group of individuals addressed by certain kinds of texts. It is this unique function of stereotypes that calls for a stereotype theory above and beyond classical cognitivist approaches. Therefore, a pragmatic perspective seems inevitable.

There is another similarity: like schemata, stereotypes are also organized within the memory’s emergent networks of experience and knowledge. Much in this manner T. E. Perkins emphasizes that the simple surface structures of stereotypes are usually connected on a deep level with highly complex caches of rational and emotional knowledge, which stereotypes access as subroutines.153