The “industrialization” of the American cinema has already led to the conveyer-belt method…. The final product is a shapeless mass, for even the best theme, after it has passed through so multifarious a filter, loses its form and originality. Industrialization is threatening to destroy the hopes which awakened in us the day the world of pictures was born.

—RENÉ CLAIR, REFLECTIONS ON THE CINEMA (1951)

AMERICANIZATION, RATIONALIZATION, FILM CRITICISM

A marked shift toward a widespread awareness of the stereotype in cinema took place in the second half of the 1920s and was prompted by the increased interest among journalists and theorists in the topic. This primarily occurred under the aegis of fundamental critique. By this time, key theoretical positions on film as art were fully developed. Based on these positions, the film criticism in the feature pages of daily newspapers and in cultural journals was widely established. There was a powerful sense of discrepancy between the theoretical imperative—particularly pronounced in Germany—to apply the traditional romantic vision of art to the new medium of film, on the one hand, and the actual practices in the mass medium, on the other. This discrepancy could not longer be simply ignored or dismissed as a mere transitional phase by authors and critics who had become film enthusiasts and knowledgeable moviegoers.

Critics and theorists now began to problematize the stereotype. They were less interested in pursuing the origins of the phenomenon in aspects of spectatorship and recipient dispositions than in examining the circumstances of production within the film industry. Economic considerations, traditionally regarded as purely external factors in contrast to aesthetics, became an increasing subject of interest. They were considered an impediment to the realization of artistic ideas, disruptive factors in the production of aesthetic goods—while appearing to grow steadily in influence. The new mass culture’s mode of operation as a culture industry was considered an aesthetic aberration, a trend irreconcilable with true art. The predominance of the economic approach to the question of the stereotype was even reflected in choices of language: it inspired metaphors such as “standardization” and the “readymade film,” in German Konfektionsfilm.1 Such terms clearly underscored what was considered a clash of opposites, between the aesthetic ideals of individuality, genuinely fresh expression, and vitality, on the one side, and the mechanical, the serial, the standardized, and cyclically produced, on the other. With respect to cinema, the term “standardization” had distinctly polemic undertones—which it does not have today among certain film historians (for example, Janet Staiger).2

Contemporary developments in film theory and criticism alone, however, hardly suffice to explain the introduction and rapid gain in popularity of this new theme. Two concomitantly developing trends of the 1920s also played a role. On the one hand, the discourse on the standardization of cinema was massively influenced by an overarching cultural discourse, by no means simply restricted to film, in which “assembly line” or “conveyor belt,” “rationalization,” and “standardization” functioned as catchwords. This discourse was influential during the Weimar Republic, and in literature studies it falls under the rubrics of “Americanism” or “New Objectivity.” On the other hand, underlying this line of thought was a trend toward widespread rationalization in the business sector, which also included the film industry and hence provided additional impetus to the debate on the stereotype in film.

After a world war, economic stagnation, and hyperinflation, Germany underwent a surge of modernization during the phase of economic stabilization (1924–1928). This led to a wave of rationalization, which pervaded the entire economy and was driven by the American money flowing into the country with the Dawes Plan. In many respects, the United States was considered an economic role model. It emerged as an increasingly strong competitor on the German market, and American efficiency was considered to be the benchmark.

The American industrialist Henry Ford became a figure of almost mythical proportions, a paragon of the new rationalization trend. Published in German in 1923, his biography was a bestseller.3 The technocratic vision it expounded, that efficient management was simultaneously the solution to social problems, fell on fertile ground in Germany. The war, the collapse of Wilhelminian society, and the many years of crisis had led to a state of emotional shock, a veritable implosion of traditional values and certainties that had left behind a spiritual vacuum. This made the segment of the public open to modernity also receptive to what was deemed a radically new spirit of objectivity.

Proponents of this thinking upheld the technological, utilitarian, unemotional, and effective aspects of modern industry’s mechanical production—as championed by Taylorist and Fordist ideas of rationalization—as a beacon of hope. In the spirit of Ford they glorified technocratic illusions. As Helmut Lethen states in his standard work on New Objectivity, society was intended to function as a depoliticized “apparatus” operated by experts.4

The “steely nature” of the engineer5 emerged as a literary topos. A great concentration of metaphors based on mechanics, machines, and apparatuses began to pervade both narrative and visual imaginations. It is certainly no coincidence that during this period the science-fiction genre ultimately achieved full form in cinema (for example, Metropolis, Fritz Lang, Germany, 1927).

Ford’s assembly line took on special significance. Together with the success of the automobile in the 1920s, the principle of the assembly line, which dictated the radical standardization of parts and labor, began its incredible triumph and became a pervasive idea. As Sigfried Giedion wrote in Mechanization Takes Command, it became “almost a symbol of the period between the two world wars”6 and undoubtedly served as a guiding cultural metaphor for the new age of fully mechanized mass production.

The currency of this topic among the general public is apparent in that the interest in, and indeed fascination for, this new phase of modernization (and the use of corresponding metaphors) was by no means limited to technocratic or progress-oriented authors. The discourse included much ambivalence in addition to affirmation, and it had another side, a resolute cultural criticism often paired with anticapitalistic attitudes held by conservatives. Many intellectual critics felt especially challenged by the new “expansion of capitalistic rationalization into areas that had thus far seemed unaffected, into the consciousness of the liberal sphere,”7 as Lethen wrote.

Topics such as seriality and standardization, including of culturally and aesthetically relevant products and in particular those oriented toward mass consumption—such as cinema—became a focal point of interest. This fueled the controversy about serial principles of production taking over artistic products, a trend perceived as ubiquitous and thus making incursions into a field that the literary and cultural intelligentsia had considered its special domain.

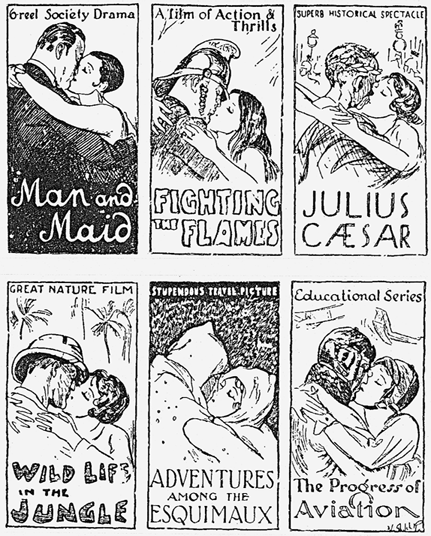

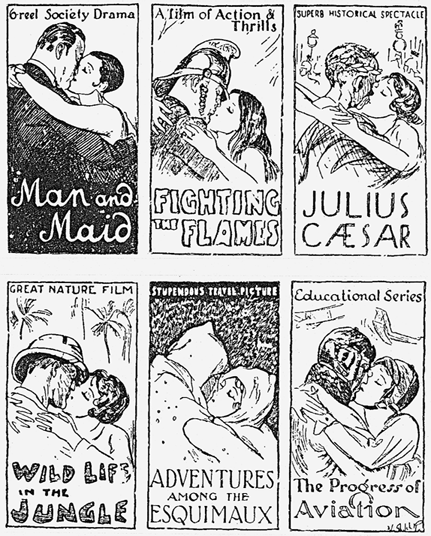

Modernists applauded the new rationality of Fordism as a purge of the obsolete, a form of cultural demystification, and democratic progress.8 The art theorist Adolf Behne, for example, had leanings in this direction. In 1929, he regarded the principles of constructivism as realized “in the daily use and daily consumption”9 of urban poster advertising (particularly for motion pictures) and considered shop-window decorating cultural progress, although he maintained a slightly ambivalent attitude. For Behne, the introduction of constructivist principles into the quotidian realm of the city street elevated “the masses to a new artistic niveau,”10 and in reverse this meant: “The painters forced into a bitter struggle for survival learn from film, from today, from the moment, from the season, from the series, from the cut, from montage, from the close-up, and from the happy end. This all applies to the niveau, the serial production of the new man.”11 Somewhat self-deprecatingly, Behne supplements this with a series of pictures caricaturizing the cinematic stereotype.12

FIGURE 10 Adolph Behne refers in 1929 to this satirical series of images from Punch.

In contrast, critics of Fordism vehemently deplored “Taylorism, standardization, and readymade production”13 in the cultural sphere. These made even the human body into a “body type”14 by destroying individuality and cultural distinctiveness. Whereas critics engaged in the prewar debate on film regarded cinema as a threat to art, because it provided a forum for coarse, garish sensuality and banal mass sensibilities and because it was feared that cinema would economically undermine traditional arts such as the theater,15 the critics of this later period viewed the serial mechanism of the global mechanical operations to which film had also succumbed as the main threat to art. Many cultural critics viewed cinema as an agent of this threat. The new guild of film critics viewed this threat, interestingly, as posing the greatest danger to their proclamation of film as art.

In 1925, Stefan Zweig’s attestation of “the monotonization of the world”16 was virtually programmatic. For Zweig it created a new “uniformity” and was much too powerful to be meaningfully combated. Meanwhile, every conscious individual was to reject it “with their soul”17—namely also, and especially, through art: “the fine aroma of the particular in cultures is evaporating, their colorful foliage being stripped with ever-increasing speed, rendering the steel-grey pistons of mechanical operation, of the modern world machine, visible beneath the cracked veneer.”18

Just as Henry Ford was regarded as a figure symbolizing the new, fully mechanized civilization, America became its symbolic land. Zweig asks: “What is the source of this terrible wave threatening to wash all the color, everything particular out of life? Everyone … knows: America.”19 Almost everyone, regardless whether enthusiast or detractor, spoke of the Americanization of German culture, or also Americanism, when referring to the new rationality, although these developments were inherent to the logic of Germany’s own economy and culture: “From the mid-decade it was the German-elaborated concept of ‘rationalization’ that dominated discussions…. German spokesmen, however, still credited the United States with originating the underlying ideas.”20 Economically powerful and indeed more advanced in the trend toward efficiency, America was considered a nation without history “lacking the retarding elements of old European societies”21 and thus also lacking any inhibitions toward worshipping the machine as well as technology, efficiency, and commercial success. Here the “mechanization … of all aspects of life”22 was pursued in its purest form. Peter Wollen remarks on the subject: “the central idea of ‘Americanism’ was provided by Fordism.”23 America appeared as the place where one could already observe the hoped-for or dreaded future of one’s own culture.

The German public’s interest in the United States increased exponentially. There was a flood of travel reports, news stories, and features from the mid-1920s onward. Between 1923 and 1928, even the number of articles on American literature increased by 400 percent.24 “Never before had so much been written about America within such a short period,”25 Erhard Schütz concluded, and “in the Weimar Republic America and the machine [became] synonymous.”26

In addition to the Ford plant in Detroit and the slaughterhouses of Chicago, Hollywood’s film studios were among the sites most frequently visited by reporters and travel writers.27 Whereas Ford’s automobile factory attracted the literati, because here they could encounter the almost mythological place of full mechanization—and not simply of a production plant but of a whole set of life circumstances (which Ford himself had described)—in Chicago the mechanized slaughter and processing of live animals into a standardized product, that is, canned meat, was a source of fascination. The view of the American film world was also guided by the motif of a mechanized and “perfectly standardized civilization.”28 Full of ambivalent fascination, Arnold Höllriegel (who had been the co-author of the legendary Expressionist Kinobuch in 1913 and author of one of the first novels to be set in the film milieu)29 described his first impressions of his visit to the Californian film city in 1927 much in this vein: “When one comes to Hollywood, one immediately notices that this place belongs to the machine, not the dirty machine of the factories, but the beautiful, appealing machine.”30 Therefore, one realizes right away, he writes in another passage, “that American film cannot be a matter of ‘art,’ that it is rather a commodity for the prodigious masses, just like canned meat products.”31 Bernhard Goldschmidt, another literary visitor to Hollywood, was one of few to express his outright admiration for the calculated efficiency of its film production: “Here too … the American has demonstrated an ability to extensively mechanize work flow by introducing ingenious machines, in order to economize on expensive human labor.”32

The motif of efficiency is even more pronounced in the writings of critical visitors. When Egon Erwin Kisch talks about the uniformity of genre films, such as the “collegian picture” and the “western picture,”33 in his reportage novel ironically titled Paradies Amerika (1929), his attention and criticism focuses on the standardization, or stereotypization, of the films. Kisch sarcastically speaks of “individuality produced on the assembly line.”34

The origins and culture-critical background of the discourse on the standardization of film are undoubtedly to be sought in this context—reportage about America and Americanism. American genre films and the symbolic place of Hollywood were subjects also often included in later accounts of the standardization of cinema.

Contemporary sources and historical research do in fact corroborate that, in keeping with the trends of other production sectors, the American film studios of the 1920s implemented division of labor, systematization, and cyclical production far more extensively than did German studios. Kristin Thompson35 and Thomas Elsaesser36 have researched to what extent German practices allowed directors more creative freedom. In contrast to most of their colleagues in Hollywood, German directors retained much greater control over the entire production process. They could influence and alter scripts. They had the authority to determine the visual breakup of scenes and could even use this freedom in order to develop completely new, experimental solutions in cooperation with cameramen and set designers. The final cut was naturally controlled by the director. He was the master of production. In America, by contrast, the main responsibility clearly lay in the hands of the producer, who oversaw a much more comprehensively standardized production process divided into specialized tasks. Whereas the director hired by the producer had authority over the actual shooting, the final editing process was, for example, passed on to an editor, who was no longer answerable to the director. The editor compiled a montage of the shots, which had been produced according to a largely standardized process of visual composition. The editor also followed a so-called continuity script, to which the director was also bound and which structured and predetermined the entire production down to the breakup of individual scenes. Thomas Elsaesser describes the continuity script as a kind of cinematographic “blueprint equivalent.”37

It goes without saying that this form of organized production entailing greater standardization, together with an overt tendency toward specific genres, aesthetically shaped the majority of films produced. However, the trend toward an increasing convergence of narrative economy and industrial efficiency did not remain limited to American cinema and thoughts entertained about it—and even less so to travel journalism alone. In the mid-1920s, German cinemagoers were able to see large numbers of American films with their own eyes. In the face of this new, powerful competition, the German film industry made exerted efforts toward rationalization, in line with the logic of the culture industry.

Although first the war and then later the weakness of the German currency during the period of inflation had largely protected the German market from imports, including film, during the so-called Stabilisierungsjahren (stability period) of the Weimar Republic the German film industry was confronted with an unprecedented wave of American exports. This played no small role in the impression of German culture being Americanized. In his study Hollywood in Berlin, Thomas Saunders describes a “cultural invasion without parallel since the age of Napoleon,”38 which began with the Dawes Plan in 1924.

In 1920, German cinemas were almost exclusively in the hands of domestic productions. In the following year, the market for imports gradually opened up. In 1923, the ratio of American to German feature films shown was already 102 to 253. In 1924—after the stabilization of the currency—it was 186 U.S. to 220 German productions. In 1925 and 1926, this ratio was then inverted, with 216 American films on the market in each of these years compared to only 212 German films in 1925 and 185 in 1926. In terms of short films, which included slapstick productions, German products were almost completely crowded out.39

Given these figures, one understands that not only outstanding works but also many average films made their way over to Germany. Looking back twenty years later at the American cinema of the period, Peter Bächlin wrote: “The danger of clichéd production ignoring all individual characteristics was clearly demonstrated in the American cinema after 1926. At the time the impetus for the large scale ‘mechanization’ of film production came from the … banks.”40 The banks had good reason for doing this, for to a certain extent the standardized productions established their own kind of quality, which was related to the mechanism that also functioned with other consumer goods. Patterns became reliable and thus sought after by the public. But the glut of American products on the German market seemed disconcerting. Thomas Saunders writes of an “overexposure to average American films”41 in terms of the productions exported to Germany and the boom of “assembly-line entertainment.”42 This gave rise to a certain weariness and to some extent aversion among members of the German public, especially critics. At the time, Siegfried Kracauer responded much in this vein: “Indeed, more than any others, the American products that have made their way to us recently—with the exception of a few astonishingly fine achievements—would have done better never to have left.”43

That the topic of standardization was taken up by German film journalism and criticism and became a leading metaphor during precisely this period certainly was significantly influenced by these changes in the films on offer—and to an even greater extent by the impact this had on German film production. After the uninterrupted business during the war and postwar periods, the German film industry experienced a considerable economic crisis44 due to the powerful competition from America in its domestic market.

Close to bankruptcy, the leading German film company Ufa was forced to come to terms with the competition. The alliance of Ufa with Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn under the logo Parufamet was considered by contemporaries to be another symbol of Americanization. Attempts followed to curtail imports through quotas and to expand markets through European alliances. There was also an effort to organize domestic film production more efficiently and to make it adhere more strictly to economic criteria. Ufa reorganized its production processes and division of labor. This was demonstrated, for instance, by the introduction of the post of production manager in 1927/1928, whose role, based on the model of the producer, was to oversee the production of a film from an economic perspective.45 The result of these changes was an obvious approximation of German products to the American model—also in aesthetic terms. Kristin Thompson aptly remarks: “Of all silent films, there are probably none that so consistently resemble those of Hollywood as the ones produced by Ufa in the late 1920s.”46

In 1923, that is, at the height of euphoric film-art conceptions, the writer Rudolf Leonhard had still proclaimed in his essay “Zur Soziologie des Filmes” (On the Sociology of the Film) that “industry does not necessarily need mass products.”47 Even if the word “industry” consistently has “overtones of the enormous, utterly organized, rational, and planned, ultimately also as something affecting the public at large,” in essence it solely means “that one has to use a machine for production.”48 That film therefore did not belong among “the ‘pure’ arts” could only be claimed by someone who “would also deny organ music, the performance of which certainly requires a complex apparatus, the status of art.”49 For Leonhard, the concept of “art” was not sociologically altered by film (with its appeal to the masses and its context of culture-industrial production) but rather the other way around. Film changed industry, “because as a work of art it is in fact sociologically classified in a different way than is a plain consumer article.”50

In light of the developments that had taken place by the end of the 1920s, such utopias and hopes for a continuity of art within the film industry definitely culminated in a crisis. However, the crisis was not perceived by the critics as a crisis of their own film-art concepts but as an aesthetic crisis of cinema. “Film-Krisis” (Film-Crisis), the title of a debate carried out in Das Tagebuch in 1928 by reputable film critics,51 became a ubiquitous catchphrase. Critics aligned with the idea of film as art understood the crisis against the backdrop of existing economic difficulties primarily in an aesthetic sense. Film was perceived to be at an artistic low, which was explained as due to attempts to reorganize and raise the efficiency of domestic production, as driven by the banks. “The enormous consumption of film ideas was naturally greater than were new creative possibilities available in response; artistic stagnation was the inevitable result, over and over the action in films circled ad nauseum around increasingly watered-down variations on story material with proven financial value.”52

In 1929, Herbert Leisegang thus described his perception in recent years of the “crisis of film.” Similarly, Willy Haas identified the source of the aesthetic crisis as the “Taylorization” that “has swept … the entire film world.”53 For Haas, the trend had negative connotations leading him to believe “that film, the first purely, inherently, and truly natural collective art, can by no means thrive in the cramped conditions of private enterprise.”54 For this reason, the author, who was otherwise considered a liberal democrat, called for aesthetically salvaging film by socializing the film industry or through “further incorporation and monopolization.” For Haas, both solutions would make it possible to satisfy immediate economic concerns and pursue an aesthetic “politics over the long term.”55

In the same year, Siegfried Kracauer also addressed the trend toward standardization. In a critical resume of the most recent German film productions of 1928, he emphasized the “employment of genre clichés [Typisierung des Filmes]”56 as one of their most noticeable characteristics: “Parallel with the consolidation of various narrative genres, a ready-made manufacturing technique has become established; screenwriters, more or less experienced directors, and their assistants use it unhesitatingly.”57 In other words, the economic crisis and the accompanying pressure toward enforced standardization exacerbated the clash between traditional romantic notions of art and the pragmatic efficiency of media operations. Many critics still retained the hope that the crisis would pass or that the public could be aesthetically educated. But instead during this crisis—which was also one of the critics’ ideas—a fundamental conflict between traditionally conceived art criteria and the culture industry’s practices simply revealed itself more fully. At this time, film criticism developed questions, a cognizance of specific problems and perspectives, which drew on fundamental cultural developments of the media age, above and beyond the immediate situation. This included—as one of the then most prevalent metaphors for the stereotype—the definitive establishment of “standardization” as topic of film theory.

THE “STANDARD” AND THE “READYMADE”: NEW METAPHORS OF FILM CRITICISM

Although the new catchword of “standardization” certainly carried positive associations in a number of cultural discourses (for example on design and architecture), there was initially hardly a film critic willing to attribute anything positive to the phenomenon.

One might say that Siegfried Kracauer ventured the farthest in this direction. His sense of film aesthetics reflected perspectives from sociology and cultural analysis. In his essay “The Mass Ornament” from 1927, he did not criticize the new rationalization in an antimodern reflex but rather embraced it as a step in the historical “process of demythologization”58 or “a stage in the process of demystification [Entzauberung]”59 in the sense of Max Weber. However, he perceived the capitalist rationale as incomplete, “murky reason,”60 because it did not take people into consideration: “Everyone does his or her task on the conveyor belt, performing a partial function without grasping the totality.”61 It entailed a tendency toward relapsing into myth, into the “mythological delusions”62 and not enlightenment and reason, that is, “serving the breakthrough of truth.”63 This caused people to subordinate themselves to the alienating organization of capitalism.64

This dialectical position may explain why Kracauer’s film criticism was not (at this point in time) opposed to popular cinema’s tendency toward seriality and genre as such. Instead, he demonstrated a nuanced view of economic rationalization, an understanding that—compared to other reputed film critics of the time—probably went the farthest: “the variation of specific patterns is in fact preferable to indiscriminate experimentation, and, besides, even the biggest firms cannot deliver new and original models week after week.”65

However, Kracauer criticized the “low standard of such operational procedures”66 and what he perceived as the backward attitudes of many films that drew on reactionary ideologies and myths and thus produced delusions. Most of all, such films nourished conformist illusions among the new class of white-collar workers regarding their social status. Standardized structures and recurring motifs did not only appear to him as constitutive of popular culture, but they interested him to a much greater extent as signs of deeper underlying ideological schemata, as indicators for critical ideological analysis, which he considered the central task of film criticism (and later of his film historiography): “In the endless sequence of films, a limited number of typical themes recur again and again; they reveal how society wants to see itself. The quintessence of these film themes is at the same time the sum of society’s ideologies, whose spell is broken by means of the interpretation of the themes.”67

That Kracauer was able to review three important books on cinema in a single article of 1932,68 which discussed the industrial nature of film production and the standardization of its products, bears witness to the significance that the theoretical motif had meanwhile attained in the discourse on cinema69 as well as to the different, and indeed contrary, perspectives it inspired.

Ilja Ehrenburg’s reportage novel from 1931, Die Traumfabrik70 (The Dream Factory), alludes to this theme already in its title, as did the essay Die Phantasiemaschine71 (The Fantasy Machine) by the Viennese essayist René Fülöp-Miller. Rudolf Arnheim also entitled two chapters of his famous film-theoretical analysis Film als Kunst—the third book Kracauer reviewed—“Schematisierung” (Schematization) and “Zur Psychologie des Konfektionsfilms” (On the Psychology of the Readymade Film).72

Both Die Traumfabrik as well as Die Phantasiemaschine bear clear relationships to reportage on America. One can hardly overlook the affinities between Ehrenburg’s book and Kisch’s ironic reports from America and Hollywood, and, appearing in the United States (at approximately the same time), the (more concentrated) original version of Fülöp-Miller’s essay had even been published as a firsthand account of American cinema in a book on theater and film coauthored with theater scholar Joseph Gregor.73

The comparison of the three texts shows that Ehrenburg, unlike Fülöp-Miller and, more significantly, Arnheim, barely touched on film’s aesthetic dimensions. The question of aesthetic quality or art seemed apparently pointless to him, given his vision of the efficient operations of the film industry, which was exclusively concerned with profit and dominance through manipulation. In a capitalistic world full of alienating assembly-line monotony, standardized dreams are produced by means of film for moviegoers who “after [performing] unpleasant work want to forget as quickly as possible.”74 He adds: “We produce films on the assembly line. Ford automobiles, Gillette razor blades, Paramount dreams,”75 and “the wasteland, the horrible consuming wasteland. That is film.”76

Hence, through a strategy of offering distractions from social misery, films promised not only to maximize profits but also to make the masses compliant. Writing from a Marxist perspective, Ehrenburg brought together the then (to some extent also among conservatives) widespread thought motifs of capitalist critique, exaggerated to apocalyptical dimensions, in a hermetic scenario of leftist cultural criticism. In contrast to Horkheimer and Adorno’s later critique of the culture industry, the Soviet author is certain of a historical solution: as an ominous reminder of the otherwise omnipotent capitalist machinery, The Battleship Potemkin repeatedly crosses the pages of the book. Kracauer’s insightful assessment in 1932 of Ehrenburg’s Traumfabrik reads: “visions of dark grandeur” that neither penetrate the “heart of the circumstances criticized” nor reveal “the constructive forces perhaps present in Europe and America beneath the surface.”77

At first glance, Fülöp-Miller seemed to play with similar images. He painted a picture of the Hollywood film industry as “this extraordinary machine which made it possible to take entertainment rolled up in strips, like canned meat in tins, and ship it to the most distant settlements. The moving picture engenders the pleasure that comes of manufacturable goods and permits the industrial satisfaction of spiritual needs.”78 Correspondingly, Fülöp-Miller also emphasized the commercial basis of film production and its affinity for standardized forms. However, in contrast to Ehrenburg he “goes about it more carefully, without the stamp of ideology, which is genuine content,”79 according to Kracauer.

Especially Fülöp-Miller’s interpretation of the “readymade” metaphor of film production interested Kracauer, who himself sometimes used this metaphor, which was prevalent at the time and which paraphrased the motif of standardization. Arnheim too employed the term as a matter of course, however with a quite a different accent. When Fülöp-Miller used the term “readymade,” he was mainly thinking about the emergence of filmic stereotypes through adaptation to common dispositions of the public. That means that he emphasized a (semio) pragmatic and simultaneously economic aspect with respect to reception: the reciprocal adaptation of product and consumer as the basis for a functioning production of goods. The garment industry (Konfektion) served him as a provocative comparison. Just as it had been possible in the readymade production of clothing to reduce customers’ different body sizes “to a few types,” so the film industry used stereotypes to create “common denominators for the wishes, feelings, temperaments, and philosophies of life of all mankind,” which made it possible to “to satisfy the spiritual needs with a standardized article which would not only be manufacturable but which would also offer each customer something that suited him.”80 Thus, the fantasy machine of cinema prefers to draw on emotional motifs, since common ground between people is found more on an affective level than an intellectual one. Cinema adheres to “everything that instinct and passion awakens,” to “the primeval myths that are a part of the sensibilities of a whole people”81—and naturally to sexual desires. The latter only really assume visual form through film, with its “standardized erotic types.”82 Thus “men with insufficient imagination” get their “ready-made dream-pictures.”83

In their overarching structure, films accommodated the widespread receptiveness of the audience for illusionary “wish-fulfillment.”84 The happy ending, an “unvarying form”85 for concluding a film, Fülöp-Miller considered as the culmination of an omnipresent compensatory tendency toward overcoming the limits of the everyday: “the film story permits itself to be completely guided by the wish.”86

Finally, he interpreted the reduction in narrative complexity (and the stereotype) as another form of adaptation to an international mass audience: “the film plot followed quite rudimentary themes which in their simplicity could be understood the world over, and their motives, which the action of the performers established, corresponded to the impulses of an instinct and inner life common to all men. Characters as complicated as the average normal man were not clear enough even for pictures.”87 Popular cinema’s affinity to the development of figural types appears to result from the trend toward reduced complexity: “Only characters with one trait could be used—characters who through their very externals and through their behavior are easily recognized as being good or wicked.”88 Both a learning effect and the pleasure of repetition played a role in reception, since “stereotyped figures”89 were gradually memorized: “Through constant repetition, these figures have gradually come to be recognized as conventional forms in whom the public can readily place its trust; like magic signs and symbols.”90 This “endless repetition of the same impressions”91 made reception additionally appealing.

Fülöp-Miller’s book is not only a—largely though undeservingly forgotten—crucial document of the incipient discussion of cinema’s culture-industrial contexts, in which film is compared with other industrial products rather than the traditional arts. In addition, it is the first book in the history of the theoretical discourse on film to lend central importance to the pragmatic interpretation of stereotypes as factors coordinating the commodity of film with the dispositions of a mass audience. This also inspired Kracauer’s praise for the book, which “in an outstanding manner derives the origins of contemporary film from the deep insights about the universal emotional reactions of the public, of which precisely the profit-oriented creative minds in the business were capable.”92

Above all, it is this first elaboration and identification of the pragmatic connection between the stereotype and audience dispositions that earns Fülöp- Miller’s text its rightful place in the history of film theory. This is not much changed by his often ambivalent or even ironic perspective on the phenomenon, which sometimes assumes the tenor of cultural criticism.

While Die Phantasiemaschine invokes the metaphorical “readymade,” or the stereotype, respectively, as the mutual adaptation of film and widespread dispositions of the mass public, Rudolf Arnheim gave the metaphor a different emphasis in Film als Kunst. He used the terms “readymade product”93 to point to the film industry’s automatization effects and thereby sought to characterize the routine nature of film production, against which he delivered an aesthetically based polemic: “the fastest, most effortless fabrication … a minimum of intellectual effort.”94 The “industry film,” as he described the majority of cinema offerings, provides endless mechanical combinations of prefabricated elements taken from a conventional repertoire, that is, from stereotypes. Indicative of Arnheim’s emphasis of the readymade metaphor was the comparison he drew with serial architecture:

The architect Walter Gropius once had the idea to build serially manufactured houses, which were not all the same, and even looked quite different, but were all constructed from the same elements; he wanted to manufacture these elements in series. The film industry produces its goods according to this very principle. Elements are predetermined and are then always fabricated in the same fashion, although they are combined in very different ways, so that new films continually result from the same material. Time and again one sees a disguise, a last-minute rescue, competition for a woman, red herrings, inheritances, chase scenes—it would not be difficult to create a chart onto which each of these films could be entered and which, much like the periodic table of the elements, would help identify gaps and make it possible to calculate which film plots were still to be invented.95

This idea does resurface regularly in later writing on film, sometimes as polemical critique, as with Buñuel96 or Shklovsky,97 sometimes as a serious attempt to actually construct such systems. Arnheim observed this sort of combination of prefabricated elements not only with regard to subject matter, milieu, story, and character types. He regarded the entire narrative structure of film down to the individual shot as determined by “schematized, preformed gimmicks”:98

The grandfather clock on which the hours are sped up, the name plate on the apartment door, the revolver pulled out of nowhere, the keyhole, the kicking silk-stocking legs with no upper body, the telltale man’s hat on the clothing hook, the death notice set in the center of the newspaper page, the monocle falling out of the eye, the champagne glass crashing to the floor, the tuxedo worn in the morning, the stage box at the variety theatre, the ashtray full of cigarettes …99

From the perspective of Arnheim’s Gestalt aesthetics, the frequent repetition of such visual ideas with established function were the most striking and, for him, the most annoying fact about the readymade. This opinion is close to the attitude of the cameraman Vladimir Nilsen, previously cited in a different context. Nilsen too expressed a particularly negative view (somewhat later than Arnheim) regarding the “standard compositional constructions”100 of film images.

When fifteen years later the film economist Peter Bächlin investigated rationalization tendencies in the film industry, he articulated, as elaborated in chapter 3, two specific trends apart from technical innovation: “1. saving work time by omitting variation superfluous to the use value of the commodities, and 2…. a typification of the end product in regard to the commodity’s use value.”101 In examining Fülöp-Miller and Arnheim’s interpretations of the readymade and standardization, one notices that Arnheim primarily discussed the first tendency mentioned by Bächlin, whereas Fülöp-Miller’s ideas tended instead to circle around the second.

STANDARD VERSUS ART CONCEPT: ARNHEIM AND FÜLÖP-MILLER

Both Rudolf Arnheim and René Fülöp-Miller brought a culture-critical perspective to bear on the topic of the film industry’s tendency toward standards. Nevertheless, as differently as they each used the metaphor of the readymade product, their views of the relationship between the standardization of film and aesthetic or artistic criteria were equally at odds.

From the very first, Arnheim’s view of the readymade film and its standards served purely as a negative foil for his theory of film as art, namely as a phenomenon unworthy of further investigation. His idea of film as art emphasizing freshness, individuality, and unique expression was directly opposed to his vivid outline of the film industry’s routinized game with building-block components: “Regularity is not odd when it concerns the production of small cars. In matters of art, however, standardization seems like a bad joke.”102

This view remained fundamentally unaltered by the insight that the conventional regularities of the “average” film are not truly static but gradually shift due to the constant integration of innovation: “The average production does not remain the same in its use of filmic means of expression. It lags an appropriate distance behind forerunning developments: what is today a bold outsider statement will be common property in two years…. Only that novelty becomes banality as soon as it is considered domesticated and legitimate.”103 The idea consistently predominates that artistic quality is defined by a maximum distance from repetition and convention and thus also by novelty and an aversion to the everyday, hence by aesthetic exclusivity.

Influenced by Gestalt psychology,104 Arnheim could have certainly shown an interest in stereotypes as a variation of repeating, incisive patterns. Gestalt psychology underscored visual perception not as compiled like a mosaic of multiple individual entities but as guided by preexisting, familiar structures—so-called Gestalten, hence the discipline’s key term. These structures reduced complexity and ensured a consistency of perception. It would have suggested itself to apply the—ultimately—constructivist basic idea of the approach105 to the interpretation of conventional forms, in particular to visual stereotypes.

However, Arnheim did not do this. Despite all his interest in basic forms, his later reflections on art and visual perception were also shaped by the notion of aesthetic development being rooted in a process of progressive differentiation. Dialectical ideas about the stereotype, like those proposed by Ernst Gombrich, another theorist of visual perception (in which conventional and reduced standard forms are indispensable to every single creative process as initial, stabilizing schemata, as starting points which are individually taken up and partially transgressed, or “suspended”),106 were not relevant to Arnheim. Thus, a Manichean pattern of thought particularly dominates the theoretical passages of Film als Kunst: creativity, originality, and exclusivity are the absolute opposites of conventional form, mechanization, and banality.

“Artistically speaking, an expression become formulaic no longer bears fruit”107 was his dictum. Against this backdrop, even the use of symbols seemed unacceptable to him. The reasoning behind this aversion recalls Mauthner’s objection to “mechanical metaphors”:

A symbol in most cases is the representation of an abstract object or process through a concrete object or process. However, and according to the use of the word this is indeed the nature of a symbol, this representation is one that has been long customary, is universally known, not brand new; and very often the significance of the symbol cannot be discerned from simply looking, rather one must have learned it by experience…. Thus it follows that symbols are not instruments of art…. The artist must create his symbols himself, and such symbols are not called “symbols.”108

Arnheim was most bothered by “the fixed clichés” of symbolism “common in mass fabrication,”109 for example the “skeletons, sand glass, people in animal cages”110 in Lied vom Leben (Song of Life, Alexander Granowski, Germany, 1931). This can largely be explained by—apart from serial aspects of production or the opposition of familiar versus new—the fact that these forms and films were generally addressed to the masses and their dispositions and not to a public of sophisticated art connoisseurs. This had to bother him, given how he claimed early on in his introduction to Film als Kunst and later often repeated that film as art “operates according to the same age-old laws and principles as all the other arts.”111 Sociologically based shifts in ideas about art did not play a role in Arnheim’s thought.

Aesthetic products with different sociofunctional accents and responding to mass needs, for example, “distraction” (as it was termed by Arnheim and many of his contemporaries), from the first did not deserve the quality seal of “art” at all. Overall he found few offerings in what the film or culture industry produced for mass reception that met his criteria. The presence of standardized forms, simultaneously adapted to the mass public, only made this discrepancy more pronounced. For Arnheim, the bond between art and popular culture had plainly been severed.

In contrast to some other prominent film critics and intellectuals of the time, who hoped that precisely film could in fact close the perceived gap between the two realms, for example through education, Arnheim clearly stated his lack of faith in such hopes already in 1928. At the time (in contrast to later on), he was even opposed to the influence of any educational ambitions regarding the public in matters of art: “The quality of higher intellectual achievements should not continue to be called into question by the already hopeless attempt at popularizing them.”112 He drastically concluded: “Let us separate, particularly in film and theater, the amusement industry from art, so that artists are not … impeded by the demands of those in need of distraction.”113 Traces of such intellectual reservations about popular culture can also be found in Film als Kunst, and they overtly characterize his indictment of all tendencies toward the stereotype.

Kracauer, who sympathizes with Arnheim’s material-aesthetic approach in his previously mentioned review of 1932, criticized this type of thinking: “At the very least his [Arnheim’s] interpretation of the ‘ready-made film’ is not original, he is still lacking in the necessary sociological categories.”114

Taken to its ultimate consequences, a theoretical approach to film as art that from the outset regards viewers’ needs for entertaining narratives as alien or even antagonistic to art means excluding the majority of the medium’s offerings from “art” and thus also from examination in film studies, which Arnheim always considered a discipline of art history.

It stands to reason that Arnheim, a film critic for the Weltbühne, was hardly in a position to rigidly maintain this stance toward the realities of popular film. He ultimately depended upon identifying positive aspects of popular film, and, being sufficiently obsessed by cinema to do so, he would discover them primarily on the level of visual form.

Film als Kunst evinces a double-layered conceptual model, which was frequently employed in the film criticism of the period: a distinction between the narrative content, on the one hand, and the more formal aspects of visual design and film technique, on the other. Arnheim was tolerant toward narrative plot structures. He was certain that “the (kitschy or reasonable) ‘action’ is not so relevant, but one must look at how the individual image, the individual scene is composed, photographed, acted, edited; Stendhal writes: il n’y a d’originalité et de vérité que dans les détails!”115

On this level, Arnheim tacitly accepted the orientation toward stereotypes, for example, recurrent plot elements, as an unfortunate condition of film’s economically necessary popularity. In an article praising the stock actor, he even celebrated the interplay of reduction, accentuation, and repetition, that is, the principles of the stereotype in regard to characters and acting.116 On a visual level, however, particularly in terms of camerawork and montage, he was never as equanimous. At the time, almost all critics, quite rightfully, associated the specificity of film, especially silent film, with its visuality. After all, precisely in the era of silent film the development of narrative cinema was dependent on the evolution and cultivation of visual techniques. Against this backdrop, Arnheim advocated a strict formalism of the image. True artistic stylization was achieved through the techniques of visual expression specific to the medium: “In terms of plot, film must, at least over the short term, make concessions to the instincts of the masses, who wish to be excited, moved, surprised. But, as always worth repeating, no concessions may be made in terms of technique!”117 This almost ideal-typical statement stems from Kurt Pinthus’s contribution to the film-crisis debate. However, in terms of content it could have easily originated from Arnheim, and it conveys his same two layers of thought. The creative development and use of visual possibilities of expression—namely those offered by the “apparatus,” the technique of the camera—was the aspect of film that truly fascinated the young Gestalt psychologist, who would explore problems of artistic expression in the visible throughout his life: “All the characteristics of the camera and of film footage, framing, two-dimensionality, black-and-white reduction, etc., become in the course of their development positively applicable artistic devices.”118 His thought on film centered on this basic theme, the use of these reductive elements of the filmic image in comparison to unmediated visual perception of reality. What he emphasized about these deficits is that they provide the opportunity for subjective intervention in the photographic process, which otherwise occurs independently, and thus also room for creativity and interpretation: “It is the very gap between the filmic image and reality, the reduction of bright colors to black-and-white values, the projection of a three-dimensional image onto a flat surface, and the selection of a specific segment of reality through the rectangular frame that make it possible not simply to mirror but compose reality through film.”119 On this level of visual design, and less in the visual composition of the mise en scène, Arnheim perceived the special aesthetic challenge presented by the medium. He thus ascribed to a concept of aesthetics within a German tradition dating back to Lessing’s “Laokoon oder Über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie.”120 The idea conveyed therein is that every art medium has its specific material of expression associated with specific mimetic deficits. This is the origin of the distinct and specific aesthetic challenges, compositional tasks, and limitations pertaining to each medium.

Along these lines, Arnheim systematized the most important means of expression of camera and montage that had been developed by 1930 in Film als Kunst and thus produced a formal-aesthetic summary of the visual expressive techniques employed in silent film. Herein lies his undisputed achievement.

From this perspective, the question of art was for Arnheim primarily a question of form in relation to the dynamic, photographic image. If the “deficits” of the film image were to be used productively in an artistic sense and in continuously new ways, then originality and innovation on this level were for him essential requirements for a designation as “art.” In contrast, narrative content and the quality of the intellectual examination of the real world remained secondary from the perspective of art—even if their political tendencies may have sometimes bothered him. According to Arnheim, the history of the visual arts was not lacking in great artworks with tendencies worthy of criticism: “The question of a film’s subject matter is greatly overvalued, particularly by intellectuals … the example of Jacques Feyder’s ‘The New Gentleman’ demonstrates how one can create a magnificent work of art out of material with objectionable tendencies. And art history is not lacking in such examples.”121

Arnheim, who had studied art history in addition to psychology in Berlin, is thus rooted in the tradition of formal pictorial analysis, which largely pervaded the art history of the period and which was undoubtedly a major influence on his work, as was Gestalt psychology.

In response to the “crisis of representation,”122 art scholars such as Alois Riegl and Heinrich Wölfflin identified the intrinsic nature of art purely with visual form. Much in the way that avant-garde visual artists pursued a path of increasingly radical abstraction, scholars who sought emancipation from the objects of representation also moved toward an autonomous history of human visual perception and pictorial forms. For example, Wölfflin had distilled these ideas from solely representational images; he studied pictures as purely visual and structural phenomena, and the content of the images essentially no longer played a role in his history of form.

Arnheim applied this approach to the dynamic visuality of film and brought it together with his interest in the possibilities of film technology, which he derived from the difference between the film image and the perception of reality. The idea of pure visual form ultimately enabled his compromising attitude toward the content and stereotypes of popular narration that underlay his double-layered model. The idea also offered a variation on the compromise with the stereotype, or from a different perspective, one might say the partial emancipation from the stereotype.

For Fülöp-Miller, more cultural analyst than art theorist, the question of art was far less significant. His interests did not lie in elaborating an aesthetic concept of film art even roughly comparable to that of Arnheim’s. And what does emerge in terms of his immanent ideas about art is anything but coherent and sometimes contradictory; it resists systematization.

Nevertheless, the tension between industry and art is expressed repeatedly. To Fülöp-Miller it seemed evident that the industry’s commercial interests, its orientation toward “clichés … in place of the rich variations of real life,”123 and a reticence toward “anything that the mass intelligence may not comprehend” have “robbed the film of the possibility of developing a genuine artistic form.”124 Without further addressing the question of “how,” Fülöp-Miller declares, however, that in cinema “constant attempts at the artistic also have been made, despite the numerous arbitrary conventions, the stifling necessity for typing and the formal ‘happy ending.’ ”125

Aside from such commendatory remarks, Fülöp-Miller’s explanation of the readymade principle was, even in terms of approach, not primarily concerned with drafting a polemic counterimage for art. His real interest lay in interpreting the film industry and films as a “cultural pattern of our time,”126 and he obviously took pleasure in doing so. Incidentally, he identified one type of film that particularly fascinated him and that in its narrative structure used the intellectual technique he himself employed of distanced, ironic observation: namely, slapstick comedy.

In the chapter on the poetry of this genre, an ideal notion of popular film emerges, which is far removed from romantic ideas about art and from the concessionary stance of Arnheim’s double-layered concept. Fülöp-Miller’s attitude indeed recalls Balázs’s glorification of the naïve, as articulated in the film-crisis debate and elsewhere. Countering Pinthus, Balázs had asked: “But does Chaplin buy his popularity with concessions?”127 The concessionary attitude thus condescendingly masked the true aesthetic challenge of popular film: “the magic of simple storytelling, meaningful and poetic without intellectual complexity.”128

For Fülöp-Miller slapstick was a form of such naïve poetry, in which individuals combat a hostile material world, a struggle intended to be watched by the viewer, not compelled to identify with the hero, from a perspective of pleasurable detachment. The majority of the figures revealed “fiendish, inimical mechanics independent of human intelligence.”129 With the playfulness of the situation made clear from the beginning, the spectator could enjoy the freedom of the action, which with great comedians always boiled down to the victory of the human spirit over lifeless mechanisms.

This recalls Brecht’s statement from the same year: “It is not right that the cinema needs art, unless we create a new idea of art.”130 Especially since Brecht considered the explicit use of stereotyped characters to be of exemplary significance: “For the theatre, for instance, the cinema’s treatment of the person performing the action is interesting. To give life to the persons, who are introduced purely according to their functions, the cinema simply uses available types … the person is seen from the outside.”131

Admittedly, Fülöp-Miller agrees with Brecht only in the rather external motif of the pleasure afforded by an overtly displayed stereotype that is not cloaked in empathy (at least in the slapstick film). However, this was not an insignificant trend in the intellectual zeitgeist, even if a recessive one. In the film-music book written by Adorno and Eisler (a project directly preceding Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment), one even reads:

As in many other aspects of contemporary motion pictures, it is not standardization as such that is objectionable here. Pictures that frankly follow an established pattern, such as “westerns” or gangster and horror pictures, often are in a certain way superior to pretentious grade-A films. What is objectionable is the standardized character of pictures that claim to be unique; or conversely, the individual disguise of the standard pattern.132

In contrast to this motif, rather typical of New Objectivity, not only Arnheim but also Fülöp-Miller associated the readymade film with a state of regression. As expressed ten years earlier in the writings of Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, the notion of cinema as “substitute for dreams,”133 now a prevalent idea, is present in Fülöp-Miller. The escape into pleasant dreams, the return to an easily understood, simple world with clear values, which functions according to wishes lodged deep in the spectators’ subconscious, to Fülöp-Miller as well as Arnheim appears to be the true core of what the play of standards in the film narratives offered. But again, both authors approached the idea from different perspectives.

For Fülöp-Miller, cinema as a whole was an apparatus of regression sui generis. Therein lay the essence of its success, which was already facilitated by its technological apparatus. One is clearly reminded of Münsterberg’s theory of film perception, in which he described how through close-ups and editing the “machine” itself guides viewers’ attention and thought processes and relieves them of mental work whenever possible.134 Fülöp-Miller rounds out this picture with a description of narrative stereotypes as vehicles of mental relief and regression par excellence. Continuing in this train of thought, his text seems to anticipate Jean-Louis Baudry’s thesis:135 “Thus we see that every conceivable effort is made to enable each spectator to realize his wish-phantasy in the most effortless and comfortable fashion, so that he has nothing to do but watch the screen in complete relaxation, freed from the eternal necessity for watchful care that real life occasions, freed from the strenuous effort of attentiveness, of the obligation to think.”136 That this orientation toward regression, combined with the search for “common demoninators,”137 led to “primary functions of the human soul,”138 that film narratives had assimilated whatever aroused the instincts and the passions (even if moderated by convention)—for Fülöp-Miller all this constituted their very nature.

Adorno would later polemicize against such regression, claiming that in the context of the culture industry it was pernicious: “The renunciation of resistance is ratified by regression.”139 Fülöp-Miller, in contrast, limits himself to simply mentioning the phenomenon. Beneath the surface, a fascination even shines through that recalls the provocative declarations from the ranks of the avant-garde during the cinema debate in the years prior to World War I. Such proclamations were aimed at rejecting attempts—made under the banner of the Autorenfilm—to elevate the status of cinema to a recognized art form (in the sense of traditional concepts of art). The intellectuals were in fact fascinated by cinema’s garish visual pleasure and its perception as a space of delightful regression.140 In 1913, Lukács appreciatively wrote: “the child that is alive in every person is liberated here and becomes lord over the psyche of the viewer.”141

Arnheim emphasizes clearly different ideas. Having committed himself to an extensive “excursion in extra-aesthetic regions”142 of the psychology of the readymade film, he too considered it beyond question that the stories consistently asserting the triumph of a naïve sense of justice ultimately addressed the unconscious wishes and desires of the spectators. This, however, gave him a sense of unease, and he felt compelled to wield his pen against the image of the “psychology of the average man,” which successful films revealed to him—“much like the psychologist can uncover the structure of a patient’s soul by the recounting of an insignificant dream.”143 It showed the extent of the prevailing “stale air in the unconscious”: “the readymade film gratifies the sluggish creature of habit within the individual,”144 and it reveals the secret “taste for small-mindedness and backwardness.”145

In the context of 1932, the film critic of Carl von Ossietzky’s Weltbühne also identified a political dimension, in that the stereotypical wish fulfillment of contemporary cinema could promote social passivity and a reactionary mentality. Film makes it possible “that dissatisfaction does not incite a revolutionary act but instead fades into dreams of a better world. It serves up the things worth combating as sugar pills.”146 Nevertheless, for Arnheim too this pleasure in the regressive unexpectedly (and without consequences for his later thinking) broke new ground:

Cinema wonderfully fills our imagination with the bogeymen that children both love and need and that they procure from one place or another. Thus we associate with cinema the same tender gratitude we feel toward our old children’s books…. Today we will sometimes go to the eighty-cent cinema on the corner, and, delighted and moved, we experience the “Lord Gray’s Night of Horror” and the “Rapture of Sin.”147

This last thought again strongly recalls the previously discussed paradoxical arguments, which were characteristic of the intellectual fascination for the non-intellectual, the “primitive,” the “childlike,” which originated in the early period of the medium and which soon became a topos, albeit recessive, in the intellectual discourse on cinema.

THE STANDARD AS A TOPIC IN EXILE: ADORNO, ARNHEIM, AND PANOFSKY

When many of the intellectuals in Germany who had contributed to the debate on the standardization of film were forced to emigrate in the 1930s and 1940s, the discourse was continued among these émigrés in the United States. The basic structure of the arguments adhered, for the most part, to the framework already established by around 1930. However, the discourse did undergo a pronounced radicalization and polarization, not least because the theorists encountered—much like the reporters of the 1920s—an even more driven and overtly commercialized media business, which belied all illusions of a temporary “crisis.”

Theodor W. Adorno later recalled that it was in America where he first truly realized “to what extent rational planning and standardization had permeated the so-called mass media.”148 Contributing to this was certainly the fact that he began his career in exile with the Princeton Radio Research Project, as did Arnheim somewhat later. The project brought the new arrivals in close contact with the American media business: Adorno was responsible for music studies, and Arnheim, of all people, was commissioned with examining the successful narrative formulas of daytime serials, that is, radio soap operas.149 Hence, it is not surprising that the standards of popular culture became a leading topic in the years that followed.

The function of this motif, again as a focal counterpoint to a positive aesthetics, was already distinctly articulated in Adorno’s essay “On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening,”150 published in German in 1938 and providing a skeptical response to the technological optimism of Benjamin’s theses on the work of art. This motif remained unchanged151 until the publication in 1947 of Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment.

In today’s cultural memory, this book functions as a paradigm of left-wing criticism of the culture industry. The text was, however, not without precedent but rather picked up the threads of the discourses of the late 1920s and early 1930s, including the discourses on the standardization of film. The book also marks the height of the culture-critical discourse on the stereotype. For Horkheimer and Adorno, the set of problems that they criticized in the culture industry culminated in the tendency toward the stereotype: “Despite … all the gesticulating bustle, the bread on which the culture industry feeds humanity, remains the stone of stereotype.”152

They emphatically raised the issue of the constant repetition of conventional, “banal” aesthetic patterns in Hollywood films and in the products of the culture industry as a whole. Nevertheless, they did not situate the core problem foremost on the level of aesthetic appearances, and in this they diverged from most of the opinions dating from around 1930. Instead, their criticism was aimed at the schematism dominating the individual’s relationship to the world and underlying aesthetic form:

The senses are determined by the conceptual apparatus in advance of perception; the citizen sees the world as made a priori of the stuff from which he himself constructs it. Kant intuitively anticipated what Hollywood has consciously put into practice: images are precensored during production by the same standard of understanding which will later determine their reception by viewers.153

The active contribution, which Kantian schematism still expected of subjects—that they should, from the first, relate sensuous multiplicity to fundamental concepts—is denied to the subject by industry. It purveys schematism as its first service to the customer.154

In “The Schema of Mass Culture,” Adorno regarded the genuinely distinctive element of this filter as operating in concert with the reified state of a society subjugated to commodity fetishism: “Perhaps the gesture of the narrator has always had something apologetic about it, but today it has become nothing but apology through and through.”155

The power of the “predigested”156 rests on the omnipresence of patterns: “the totality of the culture industry. Its element is repetition.”157 Following this train of thought, the pointedly described standardization of aesthetic appearances remains a derivative phenomenon functioning as a metaphor for the deeper-lying filters of deception.

Since for Adorno and Horkheimer the contradiction between the idea of individuality and the reality of mass culture seemed insurmountable, stereotypy—developed as a counteridea to individual expression—assumed omnipotent proportions. In this sense, they shared the Manichaean axioms of theorists such as Arnheim. However, in contrast to the former film critic of the Weltbühne, who attempted a certain degree of aesthetic nuance with his double-layered model, the two cultural theorists remained hermetic in their critique. Similar to many of the polemical reporters on America in the 1920s (such as Kisch), they considered cinema little else than the return of the “unending sameness”158 of the a priori banal. “Every film is a preview of the next, which promises yet again to unite the same heroic couple under the same exotic sun: anyone arriving late cannot tell whether he is watching the trailer or the real thing.”159 From this perspective, every individual trait, every novelty, every talent becomes a mere external guise of schematism, in which change merely means adapting to changed circumstances. But is the “Lubitsch touch”160 truly nothing more than “pseudoindividuality” or “a fingerprint on the otherwise uniform identity cards”?161 This negative hermeticism eliminates a priori stereotype concepts in the spirit of Dialectic of Enlightenment from differentiated analyses of popular film.

Arnheim’s pessimism also became more pronounced around this time. In his study on radio soap operas he concluded: “The effects of commercial control are well known from what motion picture producers and pulp writers offer to their customers. Any admissible means to exercise a strong appeal is welcome, and since generally the strongest and widest appeal can be secured by the crudest means, commercial art production tends towards lowering the cultural level.”162 He hardly saw any more chance for the realization of his idea of film art. He had meanwhile given up his hopes that, as claimed in 1931/1932, the standardization tendencies were merely the expression of a temporary crisis. Taking stock in the essay “Il cinema e la folla” (Cinema and the Masses) for the Italian magazine Cinema, he explained in 1949 that film is ultimately bound to providing a modern “spectacle for the masses”163 due its high cost of production and commercial-industrial base.

In the meantime, film production continues to industrialize, and the type of small producer who attempts to unite commercial interests with honest artistic ambitions is on the verge of disappearing. Production tends to create grand things, solely on the basis of precise calculations made from the current tastes of the audience and the processes of a rationalized and standardized mode of production.164

With the exception of a few atypical cases, the attempt to make cinema into an art fostering individual, nonstandardized expression was necessarily deemed a failure against the backdrop of the “continuous, enervating friction between the creative imagination and commercial intentions”165 intrinsic to the media economy.

In 1934, Arnheim had once described such an atypical case, Erich von Stroheim. Whereas “in Hollywood the mechanization and commercialization of human creativity have been carried to the most violent consequences … because the tendencies of modern industry have been applied to the most recalcitrant object, namely, art,” Stroheim’s work had demonstrated “the rebellion of a strong and exceptional personality against the rules and the norms.”166 By the late 1940s, Arnheim did not mention such exceptions anymore. The fact that around this time he definitively turned his attention to questions of aesthetic perception in the field of modern art and from then on barely addressed topics of film (or radio, which he had studied in the 1930s), is already prefigured in this resume. “Il cinema e la folla” is a document of departure from film. It already indicates an outside perspective.

It is interesting that in this text he explicitly takes up the topic of mechanization one more time, which, placed at the beginning of the text, serves as its central idea: “The spirit thus resists the tendency of mechanizing the relationship between the individual and reality to the extreme.”167 Two types of mechanization play a role in film: the mechanics of the photographic reproduction technology, on the one hand, which is predisposed toward technical verism, and the mechanism of the stereotype, on the other, which is likened to the task of the architect “who is to fabricate a building out of standardized construction elements.”168

In respect to the first kind of mechanism and the resulting “conflict between artist and machine,”169 Arnheim argued for a dialectical concept, a “considerate verism,”170 in which artists (in accordance with the concept of Film als Kunst) use the “deficits” of the mechanical procedure in order to assert their subjectivity without breaching the verism of the photographic process. However, he remained uncompromising toward the second type of conflict, which resulted from the transfer of “popular theater into a phase of industrialization”171 in the commercial medium of film. Here he did not use a dialectical approach to reflect on the way that standards were handled, although he did at one juncture even mention that innovation can be allied with commercial interests. Nevertheless, like Adorno, he too considered this as pseudoindividualization.

Ultimately, the problems in his aesthetic theory of cinema become transparent at this final juncture, a theory precluding all cultural sociological change and guided by a “pure” understanding of art, which, removed from the standards of mass production, was oriented toward the “eye of the connoisseur,” the exclusivity of the “happy few,”172 as Arnheim expressly stated—and (now exclusively) toward the experimental avant-garde.

But also the antithetical and instead optimistic side of the discourse was represented by a film essay by Erwin Panofsky, a German émigré art historian.173 The origins of this study are related to the prominent scholar’s support of the New York Museum of Modern Art in establishing a film department. To this end, he held the lecture “On Movies” in 1934. First published in 1936, the text appeared in 1947 in its final and substantially revised version under the title “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures.”174

Noticeable from the first is that Panofsky, like Arnheim, also pursued a double-layered mode of thought and distinguished between narrative content and visual presentation in the photographic medium. However, his points of emphasis differed from those of Arnheim’s Film als Kunst.

He turned his attention to the world of popular narrative not simply as a gesture of conciliation or critique. More clearly than hardly any other theorist of film as art, Panofsky acknowledged a form of filmic narration, which “appealed directly and very intensely to a folk art mentality.”175 This mentality was expressed in films that adhered to a “primitive sense of justice and decorum” and “plain sentimentality” and that satisfied a “primordial instinct for bloodshed,” “a taste for mild pornography,” as well as a “crude sense of humor.”176

Panofsky responded with genuine fascination to the stereotypical structures of pictorial narration, which he mainly described in the context of silent film. Known as an iconologist, the famous art historian spoke of the “introduction of a fixed iconography”177 for characters and standard situations in early film, that is, of recurrent conventional patterns. In a manner comparable to the pictorial art of the medieval period, this iconography “from the outset informed the spectator about the basic facts and characters, much as the two ladies behind the emperor, when carrying a sword and a cross, respectively, were uniquely determined as Fortitude and Faith.”178

For Panofsky, the well-known character stereotypes of film, for example the “Vamp” and the “Straight Girl” (“identifiable by standardized appearance, behavior, and attributes”),179 were “perhaps the most convincing modern equivalents of the medieval personifications of the Vices and the Virtues.”180 He saw the effects of a “fixed attitude and attribute principle”181 everywhere in cinema but considered them especially pronounced in early film.

A checkered tablecloth meant, once and for all, a “poor but honest” milieu; a happy marriage, soon to be endangered by the shadows from the past, was symbolized by the young wife’s pouring the breakfast coffee for her husband; the first kiss was invariably announced by the lady’s gently playing with her partner’s necktie and was invariably accompanied by her kicking out with her left foot. The conduct of the characters was predetermined accordingly. The poor but honest laborer who, after leaving his little house with the checkered tablecloth, came upon an abandoned baby could not but take it to his home and bring it up as best he could; the Family Man could not but yield, however temporarily, to the temptations of the Vamp.182

In early film melodramas “events took shape, without the complications of individual psychology, according to a pure Aristotelian logic so badly missed in real life,”183 and the films regularly tended to have a happy ending. This was their special charm. In this context, Panofsky explicitly argued against the aesthetic development of filmic narrative contrary to “a primitive or folkloristic concept of plot construction.”184

Here the topos of the intellectual fascination for the nonintellectual, the naïve, and the regressive was far more immediately apparent than even in the work of Fülöp-Miller. There are obvious parallels with early positions from the cinema debate that cultivated this thought motif, such as Walter Hasenclever’s apology for cinema from 1913, although Panofsky’s avowal of the folkloric seemed less paradoxical and ambivalent. Hasenclever had written:

[Film] is not an art in the sense of theater, no sterilized intellectuality; it is by no means an idea. For this reason it resists (repeated attempts at) inoculation with ethereal music: it still would get smallpox every time. The movies remain something American, ingenious, kitschy. That is their popular nature; that is what makes them good … for their modern character is expressed in their ability to gratify idiots and intellects alike, but each in a different way, each according to his mental make-up.185

Panofsky saw the beginnings of media-compatible popular narration in cinema in the same light—prior to “attempts at endowing the film with the higher values of a foreign order”:186