The nostalgia film was never a matter of some old-fashioned “representation” of historical content, but instead approached the “past” through stylistic connotation, conveying “pastness” by the glossy qualities of the image … connotation as the purveying of imaginary and stereotypical idealities.

—FREDRIC JAMESON, POSTMODERNISM; OR, THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF LATE CAPITALISM (1996)

Within the scope of classical-realist theories of film acting, much has been written about rolling back conventional patterns and acting stereotypes. These attracted particular resentment when they became all too obvious, either because as conventional acting patterns they clearly departed from corresponding everyday patterns of behavior, or because they seemed overly accentuated or vulgarized, or because they no longer seemed “truly felt” but were rather used in a masklike, symbolic, or even mechanical manner. Often all of these aspects together became a source of criticism.

Originating from the stage, realist theories of acting are not a novelty of film. Stanislavsky’s concept was simply one of the most influential theories of its kind. The reason that film-acting theories drew so readily on the realist tradition is because the mainstream was primarily interested in imaginations presented as verisimilitudinous, and on the part of many cineastes there was an interest in the redemption of physical reality (Kracauer). In contrast to the theater, the unique qualities of film did in fact offer new possibilities of intimate acting, which, based on subtle signs and nuances, seemed to forgo the criticized stereotypes.

Only a few critics of realism addressed its acceptance of conventional forms of acting. Herbert Jhering’s contribution has already been discussed (in part 1) as an example of a dialectical view of the acting stereotype. “If the cliché is infused with personal energies, then it ceases to be such and becomes the necessary freedom of the creative artist.”1 So reads his core statement. Here the stereotype seems to be an acceptable and constitutive factor of acting, and he is interested in how stereotypes are suspended when one is in the thrall of a creative individual and how they are renaturalized and reclaimed to enable the authentic expression of the actor.

In addition to the radical critique of the stereotype and the numerous strains of realist theory, there were also traditions of acting that did not attempt to conceal acting as such or the use of conventional forms—forms of acting not denying or hiding their artificial character or their inherent play with a given repertoire but that reveal and display these elements. These modes of acting, which, as opposed to the psychological-realist art of acting, can be described in terms of “performance,” have gained significance in the more recent films generally labeled as postmodern. Unlike Robert Altman’s films from the 1970s, this cinema not only has no problem with stereotypes but actually reflects the patterns found within a given genre or the history of the medium in a celebratory manner. And it does so with the same verve of Altman’s former critique.

There are many variations of the revelation of stereotypes. A primary one is acting within acting, which still bridges realistic acting. A character is played, who is in turn playing a role, whereby in strictly realistic cinema only indications of this secondary role, that is, that of the diegetic character, are revealed. This is an interesting task for actors, since it calls for an inner split of the character. However, other variations clearly transcend the limits of the realistic tradition: grotesquely comical acting, for example, which systematically overdoes certain outrageous ticks and often displays (as in slapstick) the uncontrollable mechanics of stereotypical sequences of expressions or movements. Or stylization through accentuated, repeated poses and finally the disruption of empathy through the split between the actor and the role in the sense of Brechtian techniques of estrangement (Verfremdung). James Naremore has enumerated and elaborated all of these techniques.2 What he does not discuss in depth, however, is a variation of performance that, although not fundamentally new, has proven to be particularly important in the cinema of the last decade: the play with historical reminiscences, the emphasis on intertextual recall of historical acting stereotypes. Even acting styles thus become connotative of the imaginary’s past.

Watching Jennifer Jason Leigh in her roles, one soon notices that she is an actress for whom the emphasis on acting as acting and the emblematic use of repeating forms have special significance. Her role in The Hudsucker Proxy (Joel and Ethan Coen, 1994) is an example of performative recourse to historical acting patterns. Leigh and especially her appearance in this film therefore deserve closer scrutiny.

AN EMPHASIS ON PLAYING WITH THE ACTOR’S REPERTOIRE

Jennifer Jason Leigh, born in 1962 in Hollywood, began her career as an actress in film and television productions in the early 1980s, when she was about twenty years old. Since then she has made an extensive series of notable film appearances,3 including no small number of leading roles, especially since the 1990s. In other words, today Leigh is a recognized actress, but she is not a star in a narrower sense of the word. This has to do with the types of roles she plays, her specialization in characters not readily accommodated by popular ideals. Although often central characters in their respective films, they are never characters that invite straightforward identification.4 Neither the “pretty woman,” the “erotic dream,” nor the wholesome “girl next door” intended to win the sympathies of the audience are part of her on-screen image. Although still youthful, even early on in her career she embodied characters not given to happy and uncomplicated symbolism. At the same time, the range of her roles is remarkably broad and varied. She typically performs her parts with excessive abandon, often without fearing ugliness—indeed sometimes priding in the ugly. As unique and incisive as Leigh’s characters appear, one might cautiously generalize that her obvious specialty are women with some sort of defect. As viewers, we are affected by her performance but always from a perspective similar to analytical distance; her characters appear as if under glass.

These women often seem tortured and in a bad mood, depressed and aggressive. They gesticulate dismissively and curse obnoxiously, unsatisfied with their lives but hardly able to extricate themselves from their palpable dilemmas. They also display destructive traits that are almost impossible to control and sometimes directed against themselves. But one could never describe them as women who accept their lot and surrender, at least not before they are finally broken. They defiantly put up a fight and try to dominate the men around them, at least verbally and in gesture. In general, they tend to assume a position of superiority in their dealings with others, or they try, though sometimes ineffectually, to take on this pose. However, this attitude is connected with flashes of insight into their private lives, the fragility and loneliness hidden behind all the assertiveness.

Putting on an act of superiority seems particularly fitting when Leigh plays the part of the confident, emancipated intellectual: for example, the initially self-assured and celebrated computer expert Allegra Geller in eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999) or the writer Dorothy Parker in Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (Alan Rudolph, 1994), who manages to achieve success in a male society—thereby revealing an ambition taken to the point of egocentric cynicism—but increasingly experiences an inner emptiness.

However, social outsiders are also part of her core repertoire: the harbor prostitute Tralala in Uli Edel’s Last Exit to Brooklyn (West Germany/USA, 1989); Sadie, the desperate little bar singer in Georgia (Ulu Grosbard, 1995); the phone-sex operator Lois in Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993); or the wannabe hardened gun-toting Blondie O’Hara in Kansas City (Robert Altman, 1996). Even coming from a socially inferior position, these female characters are marked by their will to assert themselves at all costs. This is expressed in an overtly displayed air of superiority toward the men who desire them, an attitude often verging on contempt. This gesture of dominance often seems clearly recognizable as an assumed mask concealing desperation or emptiness, and even the ambition to dominate is itself felt to be the result of a precarious inner state. This drive for the upper hand combined with the masking of other emotions and a sense of desperation repeatedly borders on the psychotic. Leigh took this attitude to the extreme as Hedra Carlson, who, driven by extreme jealousy, tyrannizes the woman sharing her apartment with diabolical brutality in Single White Female (Barbet Schroeder, 1992).

Her tendency to play characters of such psychologically extreme conditions, in a kind of self-masking that does and should remain transparent, as a variation of the role-within-the-role, seems to be part of Leigh’s special acting skills. Rarely do we experience her in parts characterized by moderate moods or tones. Neutral behavior combined with reserved gestures, as in daily life, are almost completely absent in her acting. She tends to swing between sharply accentuated extremes. As the prostitute Tralala, she shifts almost seamlessly from a flood of high-pitched curses and bitter sarcasm, on the one hand, to a fragility revealing sadness and even desperation, on the other. She unifies these two states through a marked mask of feigned indifference clearly articulated as the social façade of the prostitute. Similar alternations between extremes played in overtly harsh tones is the mark of most of her major performances.

In keeping with her disposition to such accentuations, Leigh seldom speaks or acts without carrying out multiple and precisely calculated symbolic gestures. The film Georgia is a good example. At the low point, the unhappy Sadie, wracked by alcohol and drugs and close to breakdown, tries to buy a ticket at an airline counter for her flight home. Oscillating between helplessness and aggression, she leans across the counter and berates the airline employee; garish facial expressions (in medium close-up) accompany spastic hand gestures. Similarly drastic performances, demonstrating Leigh’s ability convey a panoply of ugliness, can be seen in Last Exit to Brooklyn and Single White Female.

However, she also exhibits this tendency of strained gesture in less dramatic scenes, in which this inclination is subdued for a few moments in favor of a quieter, less forced mode of acting. For example, at the end of Georgia the character is marked by an atypical, obviously unusual state with moments of calm and relaxation. But more characteristic of her acting is Sadie’s dialogue with her sister, the more successful country singer Georgia. While the latter, although clearly upset by the conflict with her sister, remains calm while unpacking a bag of groceries, her insecure little sister, a failed singer and verging on alcoholism, is in constant motion. She seems compulsively agitated. While talking, she leans over the kitchen counter and swings her legs; she pulls at the front of her dress, strides around the room with an assumed cool and casual air; she mumbles her words and gathers together a pile of bedsheets with demonstrative carelessness; when talking, she hits her forehead with the palm of her hand (as a recognizable exaggerated gesture of sudden, self-ironic realization); she uses the conventional gesture of the raised thumb as a sign of happy, pretended agreement and grimaces when she speaks with the corners of her mouth contorted. Her tone alternates between the display of a good mood and pretended coolness, on the one hand, and sarcasm, on the other. During the dialogue, her gestures characterize an insecure girl trying to seem strong in front of her sister, while her almost desperate mood and the tension with her sister come through clearly.

This demonstrates Leigh’s affinity for playing characters who themselves are playing a role. In such moments, one of their specific traits is accentuated. One seldom has the sense that she derives their gestures from her own personal experience, let alone intuitively allowing them to erupt from within. Instead, one consistently senses a performative intelligence at work, which is based on a precise, almost analytical observation of a repertoire of behavioral forms associated with the given social and behavioral roles of her female characters. From this repertoire Leigh carefully selects typical individual forms, gestures, movements, physiognomic details and uses them—in intertextual repetition—in a forceful and condensed fashion. This is how she veritably constructs her characters while only partially “renaturalizing” them. Despite all their intensity, Leigh’s female characters remain recognizable as artifacts clearly belonging to the world of the film, precisely because of their sharply exaggerated outlines. This results in the previously mentioned sense of observing them as if under glass. As viewers, we watch these strange beings with almost analytical interest, yet in certain moments of the performance they are also able to move us.

The latent recognizability of her roles as artistic products, as forced constructs of forms deriving from the careful observation of a repertoire of gestures and facial expressions, this fundamental, unique quality of her acting corresponds to an affinity to characters who themselves are putting on a role in film diegesis. For in such cases the actress (as an additional factor) also has to convey the nonimmediate quality of the gestures. Such recognizability is the intended result of an intelligent and confident form of acting. At least in terms of some of her roles this also predisposes Leigh toward an involvement in the type of (postmodern) cinema that displays its artificiality and, like Leone’s Western, makes no secret of celebrating a repertoire of filmic stereotypes.

Much in this sense the Sight and Sound critic Lizzie Francke remarks that Leigh’s prostitute in Uli Edel’s Last Exit to Brooklyn is “a study in a particular style of acting”: “Tralala seems to be played strutting along the waterfront imagining she is Jane Mansfield.”5 This brings us to an additional facet of Leigh’s abilities, historical-intertextual role playing. As competently as she observes social behaviors of women in daily life as a basis for developing acting schemata, she is similarly capable of accurately analyzing, intensifying, and symbolically using acting styles from other periods, with their unique characteristics, tics, and historical stereotypes.

SECONDHAND CONSTRUCTIONS

This latter ability may have been decisive in the Coen Brothers’ casting of Leigh in the role of the newspaper reporter Amy Archer in their film The Hudsucker Proxy. Here she could give full play to her taut, highly accentuated acting style, which does not conceal but emphasizes acting as acting. Here she could perform her roles within a role, thereby condensing an analysis of specific acting styles and stereotypes from other periods of film history into a performance replete with allusions.

The concept of The Hudsucker Proxy provided the appropriate backdrop. On the surface, the film is presented as a kind of screwball comedy. It combines elements of extreme caricature with slapstick and benignly ironizes familiar story stereotypes: of social rise, fall, and recovery, of love, crisis, and the happy ending. On another level, the film provides a knowledgeable audience with a dense, multilayered, historical-intertextual fabric, which unfolds almost exclusively in references to classical American cinema. We experience a film no longer really based in “extrafilmic” reality; it instead proves to be an intertextual product par excellence, for which the imaginary world of classical Hollywood serves as the actual point of reference. The most important models for the core plotline are Frank Capra’s films of the late 1930s and early 1940s, which merge comedy and social fairytale: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and Meet John Doe (1941). As in these three films, which share a family resemblance, in The Hudsucker Proxy a young man (Tim Robbins), initially portrayed as a simpleton, comes from a rural town to New York, where he experiences an incredible social rise. In the process he is, unbeknownst to him, subject to the manipulations of a group of powerful men headed by a dastardly capitalist. In true Capraesque fashion, the capitalist uses the naïve new arrival as a kind of straw man behind whose back he is able to go about business as he pleases and consolidate his power. And he lets the newcomer fall by trying to destroy his public reputation once he is no longer useful and even begins to disrupt the capitalist’s play for power by making his own decisions. Among Capra’s regular cast of characters is the story-hungry female reporter who finagles the hero’s trust, either in order to cooperate with the manipulation or to expose him as a useful idiot, as in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and now in The Hudsucker Proxy. However, the reporter, Leigh’s Amy Archer, falls in love with the hero—as usual in Capra—as he does with her. Over the course of the hero’s fall he unmasks her dual role, just like his cinematic predecessors, and rejects her. Finally, the story of professional intrigue takes a happy and particularly fairytale-like turn for the young hero, and the romance is resolved with a happy ending.

The classical construction of The Hudsucker Proxy simultaneously uses key narrative scenes and typical figures from previous films and accentuates and distills their repetitive distinctive features, so that a scene in part seems to be distilled from multiple variants of similar scenes. In other words, this is a classical way of contouring the stereotype beneath the surface of the similar. The multiple references range from costume and make-up (for example, the appearance of Mr. Hudsucker unmistakably recalls that of the capitalist Edward Arnolds in Meet John Doe) to decoration, the composition of the images, and individual visual concepts. And Capra is by no means the only source of reference. The Coens relocate the rise-and-fall story in a skyscraper, in which rise and fall can be directly staged in a spatial dimension. For example, there is the elevator ride—recalling Lang’s Metropolis (Germany, 1925/1926)—from the depths of the building’s nether regions, the mailroom, up to the immense executive offices at the top; this has numerous precedents, for example, Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), King Vidor’s The Fountainhead (1949), or, again, Lang’s Metropolis. Also, the circle of board members constitutes a true stereotype, which reappears in an endless number of American films from the 1930s through 1950s, as a place where the plot points are set and insight is provided into the motives of the powerful. This group of board members particularly resembles that of The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948). Social downfall is visualized as an actual fall to the depths. Apart from the skyscraper and the attempted suicide from its top included in Meet John Doe (which The Hudsucker Proxy alludes to even down to the inner montage of the shots accompanying the distraught hero on his way to the skyscraper), the film is a fusion of almost the entire genre of classical skyscraper films, from Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! (1923) to King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928), John Farrow’s The Big Clock (1948), Robert Wise’s Executive Suite (1954), and Edward Dmytryk’s Mirage (1965).6 The closest reference is to the comedy The Horn Blows at Midnight (Raoul Walsh, 1945), from which the plummets from the skyscraper are recreated even down to the specific framing of individual shots. Grotesquely hanging, like Tim Robbins, from a ledge of the top floor, the star comedian Jack Benny falls just as the great clock strikes midnight.

FIGURE 11 The distraught hero on his way to leap off the skyscraper: Meet John Doe (1941) (left); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) (right).

Thus a patchwork is created—but also a partial synthesis, a layering of similar motifs, which in synthetic form usually no longer clearly recall any single film. Rather, a network of overt stereotypes from classical Hollywood genres emerges, and it enables the film to appear, in Genette’s sense, as a hypertext of indirect transformation and imitation.7 The playfully ironic approach to stereotypes evokes the character of pastiche,8 but much more than a mere pastiche of Capra. Instead, what emerges is an homage to classical Hollywood cinema in general. This is also indicated by the strange timelessness of the film, whose plot is purportedly set in 1959, but the 1950s are merged with the cinema age of the 1930s and 1940s, not only in the modeling of the story but also in the decorations and sets, which summon a familiar yet alien imaginary world. This is a paradigmatic example of what Fredric Jameson describes as “the waning of our historicity” in nostalgic retrocinema with its “stereotypical past.”9 For Jameson, this “distance of a glossy mirage” is typical of postmodernity, as is the suggestion that the narrative is “set in some eternal thirties, beyond real historical time.”10

Already the opening images of the film leave no doubt that the entire plot unfolds in this world of cinematic imagination. Deep blue images take us on a flight over New York at night. These pictures immediately betray that this is not the real city but an imaginary New York, a fairy-tale world. The entire film was shot in the studio with carefully and expensively constructed Art Deco sets. This nocturnal shot of New York, meticulously and painstakingly constructed as a gathering of classical, stepped skyscrapers that do not appear in this condensed form in actuality,11 does not conceal that this is an imaginary world. Both through the narrator’s voice accompanying the credits and the décor the viewer is introduced to a world characterized by that atmosphere somewhere between realism and the imaginary so typical of the sets of 1930s and 1940s cinema.

However, the comedy is not simply nostalgic effect. It joins the sentimental attitude with benign irony and an element of analyzing and deconstructing its precedents. In order to achieve this, the film multiplies, condenses, and heightens its set pieces and stereotypes, including those of acting, often to the point of the grotesque. It thus strips away the melodramatic and sentimental substance so prevalent in Capra’s films. At the same time, the social ideals for which his heroes strove are eliminated. They are replaced by efforts made on behalf of absurd inventions, such as the hula hoop. Furthermore, all the characters appear as caricatures who are completely absorbed by their two-dimensionality. Film reviews tended to mention their proximity to comic-book heroes, which are perceived without emotion because they embody pure stereotypes.12 This is particularly apparent with the stock characters, which in turn refer to the stock comical characters of the classical screwball comedy but are here exaggerated to the utterly grotesque and therefore incapable of uttering much more than a punchline or a single scream.

Resonating with moments of pathos, Capra’s films had a sentimental-comical appeal to U.S. audiences and were ultimately intended as serious. They were conceived to support New Deal politics and defend American society’s ideal of individual rights against the excessive mafioso corruption of capitalism, which blossomed in the era of the Great Depression. This attitude of mobilizing the audience with the sincere, direct appeal of the stereotype is overwhelmingly alien to the creators of The Hudsucker Proxy, the disillusioned offspring of the Reagan era. From their distanced historical perspective, they analytically extract unintentionally comical aspects of Capra’s story constructions and deconstruct the prevailing mechanisms of Hollywood’s fairy tales by openly displaying and exaggerating them and letting them tip over into the grotesque.

This is once again made clear at the end of the film. Inhabiting the great clock tower of the Hudsucker Building and equipped with visionary powers, Moses, the African American warden of the clock initially serves as a classical extradiegetic frame narrator in the voiceover accompanying the opening credits.13 Over the course of the film, his status changes to that of a diegetic character, who repeatedly assumes the function of the extradiegetic narrator and is, for example, able to address film viewers directly. At the end of the film he then, as a diegetic figure, paradoxically takes the story into his own hands.

François Truffaut once expressed his admiration for Frank Capra: “He was a navigator who knew how to steer his characters into the deepest dimensions of desperate human situations … before he reestablished a balance and brought off the miracle that let us leave the theater with a renewed confidence in life.”14 Truffaut associated this dramatic effect with “the secrets of the commedia dell’arte,”15 based more on convention than illusion. Whereas in Capra the dramatic deux ex machina held a hand over the fallen hero and ultimately helped him back on his feet while always remaining thinly shrouded in the coherent world of the narrative, in the Coens’ film this mechanism is not only clearly displayed but also personified. Moses, the keeper of the clock, is able to stop time by inserting a broomstick into the gears of the clock and thus halt the hero just before he is about to hit the ground. The jump in time so produced not only allows the hero to flop harmlessly onto the street, but it also serves as an entry for an angel (another Capra motif from It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946, and also found in Walsh’s The Horn Blows at Midnight), who ensures the happy ending. The diegetic figure of Moses turns around to us in the process and asks whether we could have come up with a better solution? The stereotypes of Hollywood fairy tales could hardly be revealed and deconstructed more conspicuously.

This also applies to the newspaper reporter Amy Archer, both in terms of her narrative development and Jennifer Jason Leigh’s acting. Here, in a comedy role, she fully capitalizes on her proclivity for pointed performance and even takes it to extremes against the backdrop of the film’s comical strategy. Here her technique of adapting historical acting styles is much more pronounced than usual.

The figure of the female reporter is an important character type in the American cinema of the 1930s and had appeared in the Capra films Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Meet John Doe, respectively with Jean Arthur and Barbara Stanwyck as the reporter. In addition to such films only partially set in a newspaper milieu, the figure of the female reporter appeared in a whole series of explicit newspaper films, a popular genre of the 1930s. Whereas the newspaper setting represented extreme modernity in its filmic iconography and the clear display of cynicism among the reporters readily corresponded with the disillusioned mood of the audience in the Depression era—as did the concomitant cinematic popularity of the gangster—the female reporter reflected ambivalence. On the one hand, departing from the traditional representations of women’s roles, the character stereotype was exhibited as an attractive symbol of modernity (and emancipation). On the other, it was also clearly readable as a sign of crisis. Usually, the woman reporter initially seemed tougher and more cynical than her male colleagues, only to then return to a greater emphasis of more traditional female values, either through marriage or a conscious, moral rejection of the brutal practices of the profession.

The most significant departure from this pattern of the turnaround, which Capra also employed, appears in Howard Hawks’s His Girl Friday (1940). Played by Rosalind Russell, his female reporter Hildy even forgets her decision to marry someone outside the field and leave newspaper work while in the midst of an exciting story. She displays the filmic characteristics of the female reporter from this period, and she shares most traits with female reporters from other films, but with heightened emphasis. This includes incorporating numerous behaviors and gestures that had previously been connoted as male, such as casual smoking, hectically taking off and putting on clothing, or the handling of hats in the heat of a story.

Hildy is not only equal but superior to her male competitors; she is at least equally quick-witted and capable of confident, cheeky, and blunt exchanges with men. Like her female colleagues in the two Capra films, she is characterized by her sly tricks and ability to make quick decisions. This is externally expressed by a marked tendency to deliver fast dialogue, which additionally accelerates the breakneck tempo of the screwball comedy. She is spatially framed by the typical décor of newspaper films, the usual editorial offices with their telegraphs, typewriters, and telephones, the “principal instrument[s] of this world,”16 as Cavell says. Russell and the actresses in the other films use these instruments frequently and hectically, not least in order to lend their characters additional dynamic and professionalism.

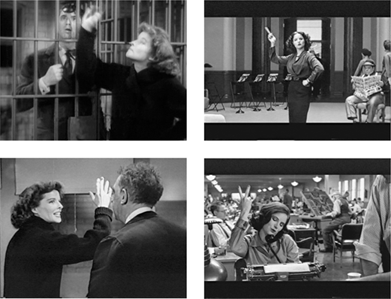

FIGURE 12 Gesture of superiority: Katherine Hepburn (left) in Bringing Up Baby (1938) and Jennifer Jason Leigh (right).

The Hudsucker Proxy picks up on this type. In terms of plot, this occurs with a Capraesque variation of the moral reversal caused by a romantic relationship. However, already the manner in which the scenes are staged foregrounds the Coens’ fundamental approach. Individual scenes refer to, usually multiple, precedents. These are then compiled, almost like extracts, and the comical refraction they sometimes entailed is now enhanced. For those familiar with classical cinema, the stereotype seems even more pronounced than before. For those who are not, there is nevertheless a sense of reduction and exaggeration, just as in a comic.

Exactly this approach is reflected in Leigh’s performance of the character. Using behaviors similar to those of the female reporters in the model films, she combines a series of acting patterns and attitudes employed by actresses of the era. In characterizing Amy, Leigh thus engages in the typical exchanges and verbal dueling of the newspaper office as well as the customary actions of the individual female reporter. Not only the previously mentioned actresses who played reporters, Arthur, Stanwyck, and above all Russell, are incorporated into this process, but so are other screwball-comedy actresses from the 1930s who projected the image of the confident, quick-witted woman. This includes Katherine Hepburn, for example, whose triumphal gesture of the raised arm belongs to Amy’s standard repertoire.17

True to her forced acting style, Leigh clearly compiles the tics and acting stereotypes of her precedents and gives them additional emphasis. For example, Rosalind Russell’s Hildy underscores her character of the hard-boiled reporter through a set of behaviors and tics, which semiotically represent the world and dynamics of the newspaper as well as confident dealings with men. In addition to the fast tempo of acting and talking already mentioned, this includes constantly handling phones, high-speed typing, provocative smoking, and, most of all, hectic dual actions: typing while speaking with someone else or talking on two telephones at once. In addition, in condensing her character Russell did not omit employing a degree of irony—intrinsic to comedy—in the portrayal of the typical behavioral patterns of female film reporters.

Jennifer Jason Leigh now extensively draws on this repertoire and presents it in the form of an extract, comparable to the overarching strategy of the Coens’ film. Amy is not only able to do two things at once, but she condenses multiple symbolic behaviors almost to the point of simultaneity. She types her article in a newspaper office shown with a depth of field similar to that of Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) and uniting all the insignias of 1930s newspaper films. She can talk on the telephone while typing and talks just as fast if not faster than Rosalind Russell. She glibly counters her male sidekick, is able to take his cigarette from him, smoke, and also provide a fitting solution to a crossword-puzzle editor in the background, who seems to be a blend of all the editorial attendants of the genre. If Russell’s biographer already described Hildy as “super-charged” and equipped “with almost giddy eccentricity” and “breakneck verbal slapstick,”18 then Leigh is able to tighten the screws a full rotation to exaggerate this to the point of the grotesque.

Nonetheless, she still develops a coherent character. As Amy, she can fully display her affinity for role playing. She not only remains a celebratory performance of loud, symbolically implemented secondhand stereotypes, and thus palpably artificial—to an even greater degree than Russell’s Hildy—but much about her remains aloof and reflexive. Different role models dominate in different scenes. Toward the end of the film the attributes of the hard-nosed reporter give way to a more melodramatic repertoire—as dictated by the story—which is, however, demonstratively performed with similar detachment. Already in the scene in which Amy meets the main male character, Norville Barnes, she has much more in common with the model character of Jean Arthur from Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town than Rosalind Russell’s Hildy.

FIGURE 13 Smoking as provocation: Katherine Hepburn (left) in Bringing Up Baby (1938) and Jennifer Jason Leigh (right).

FIGURE 14 Hectic activity at the typewriter: Rosalind Russell (left) in His Girl Friday (1940) and Jennifer Jason Leigh (right).

FIGURE 15 Fainting as pretense: Jean Arthur (left) in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Jennifer Jason Leigh (right).

This episode is also interesting, because in comparison to the parallel scene in Capra’s film it becomes clear to what extent the strategy here is aimed at the display of acting, the sketch-like fun of the role within a role. In both cases, the reporter is trying to arouse the protective instincts of the hero by pretending to faint and thus create an opportunity to meet him. Jean Arthur plays this in such a manner that her immediate acting gives almost no hint of her fainting as pretended; it is almost acted like a “real” faint, even if somewhat fitfully. The viewer understands she is putting on an act through the context—and particularly by her announcing the trick beforehand to the men accompanying her in a taxi, which preserves the diegetic coherence.

However, this very element is omitted in the parallel scene of The Hudsucker Proxy, similar to the black clock warden’s interference in the narrative. Leigh’s feigned act of fainting is expressed clearly as play within play, for example, through controlling glances recalling the demonstrative explicitness of silent slapstick cinema or by poking herself in the eyes to cause tears. Here too there are two observers, a pair of taxi drivers (who from their appearance could have stepped out of a 1930s or 1940s film). They, however, are assigned a commentary departing from the diegetic logic of the film, and their task is to intradiegetically remark on the action as a (familiar) story perceived against the backdrop of intertextual experience, elevate the scene to a paradoxically reflexive level, and finally create a break in coherence. This all serves the film’s strategy of exposing the mechanisms of the comedy genre to make them the object of laughter.

In sum, one may say that Leigh’s comical performance in The Hudsucker Proxy exemplifies a high point of her specialty in pronounced, highly accentuated acting, in which she compounds and then enhances an analytically selected comedy repertoire of gestures and traits. The basis for this repertoire is not rooted in an observation of real, everyday behaviors but in the comic interpretation of recurring idiosyncrasies and stereotypes used by comedians in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. The manner in which Leigh performs the character thus corresponds precisely with the aesthetic principle of retrocomedy. It serves as an example of the reflexive, celebratory approach to acting stereotypes and provides entry into the almost fully self-referential world of this film.