Gin was the first urban drug. It exploded on the scene among poor Londoners in the early 1700s. Nearly overnight, it transformed neighborhoods into ghettos, mothers into whores, children and fathers into sloths and murderers. The “gin craze,” which lasted for thirty years during the first half of the eighteenth century, has remarkable similarities to the crack cocaine epidemic that swept through American cities in the eighties. By some accounts, it was worse.

Gin was first invented in Holland by the eminent professor and physician Franciscus de la Boe, otherwise known as Dr. Sylvius. He called it genever. When William III, a Dutchman, took over the English throne in 1689, he brought a taste for gin with him, making it the official “pouring spirit” in the palace at Hampton Court, where privileged folks began to call the banquet hall the “gin temple.” Then William introduced the liquor to the masses. Big mistake.

Due to any number of circumstances, over the next two decades, gin made of dubious ingredients became the first liquor available in large quantities at cheap prices to the common man and woman. Up until this time, beer was the drink of choice among London’s working classes. But by 1725, according to one government report, there were 6,187 “houses and shops wherein geneva or other strong waters [were] publicly sold.” And this number didn’t include the hags who sold gin in thoroughfares the way hot dog vendors sell their wares today—“in the streets and highways, some on bulks and stalls set up for that purpose, and others in wheelbarrows.”

As Lord Hervey, a contemporary, described the gin craze: “Drunkenness of the common people was universal; the whole town of London swarmed with drunken people from morning till night.” The city’s population dropped drastically during this time. (There were some seven hundred thousand people living in London then, the equivalent of Columbus, Ohio, today.) Whole industries tanked as the working population, tanked as well, failed to show up.

Women actually drank more gin than men; that’s why the liquor was known as Madam Gin or Mother Genever. Would-be mothers destroyed the fetuses in their wombs as they drank themselves senseless. (Who knew of fetal alcohol syndrome back then?) Even the hangmen in town were known to be wasted while they worked on the gallows. At sunrise each morning, bodies lined the streets of bad neighborhoods—the living and dead. The gutters were filled with vomit and excrement.

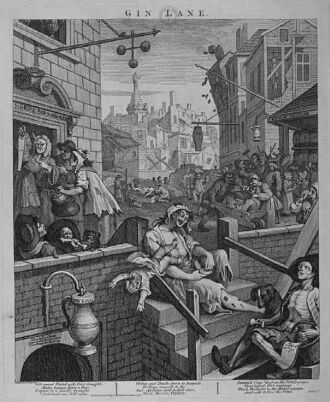

Gin Lane, William Hogarth (1751). (Image courtesy of the Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

The crude gin was brewed in common distilleries by hacks all over the city. In order to keep it cheap and still increase profit, as Samuel Johnson pointed out at the time, the distillers made their spirits “thrice the Degree of Strength required, by which Contrivance, though they pay only the Duty of one Pint, they sell their Liquors at the Price of three.” Johnson warned that any attempt to deny the working class their gin would push them “almost to rebellion.”

As neighborhoods began to collapse, journalists started reporting sensational accounts of gin-fueled urban blight. According to stories in publications like The Gentleman’s Magazine, a predecessor to men’s mags like Maxim and Playboy, boozers would drink so much gin that they would suddenly burst into flames, after which “their bowels came out.” A dozen spontaneous combustions were reported in the eighteenth century in or near London. The apparent culprit: gin.

Alas, as historian Jessica Warner notes in her recent book Craze: Gin and Debauchery in the Age of Reason, gin, like the nasty neighborhoods where it first got a foothold in England, was destined to be gentrified. In order to quell the devastation in the streets and to ease the strain of the health crisis, British officials drew up the Gin Acts of 1729, ’33, ’36, ’37, ’38, ’43, ’47, and ’51. Slowly, gin became tougher to come by. From 1700 to 1771, excises on the liquor grew 1,200 percent.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, only the well-off could afford the stuff. In response, a new group of distillers sprang up in London, men who aimed to make the finest-tasting liquor they could, liquor with integrity meant to be consumed by the educated class. The more refined the gin palate, the more refined the liquor itself had to be. The competition among distillers grew fierce, as several brands began to pop up throughout the city, fighting for their portion of the market.

Eventually, one of those brands was destined to win out, to become (in my mind at least) the finest gin ever made. It was known as Beefeater London Dry Gin.

If you pick up a bottle of Beefeater today, a formidable figure is striding as if he’s about to walk right off the label. The man’s dressed in an absurd outfit: a red, black, and gold cloak, red stockings, white gloves, bows at the knees and ankles. He’s wearing a black hat and what looks like a giant powdered doughnut around his neck. (Keen gin drinkers will notice that the fellow on today’s bottle—with a stylish goatee of brown hair—is considerably younger than the Santa Claus look-alike who used to be on the label. Looks like a focus group got ahold of this one.)

Also on the label, the name James Burrough is written—no fewer than ten times. So is James Burrough the guy in the ridiculous outfit? Did he like a chunk of beef with his liquor or was Beefeater the name of some happening nineteenth-century gay bar? Fact is, that guy on the bottle isn’t James Burrough at all. In fact, the guy on the bottle has nothing to do with gin. He was dead long before the liquor gin was ever invented. More on that later.

James Burrough, the founder of Beefeater gin, was a young man from Devon who had a fascination with liquor and distillation. Burrough founded a small distillery on the river Thames in London way back in 1820. It was the very same year that, many miles to the north, one Johnnie Walker first opened a shop in Kilmarnock, Scotland, where he sold single-malt whiskies. What a banner year for alcohol.

Burrough and Walker had a lot in common, just as gin and whiskey do. Both liquors are indigenous to the place where they come from. In Scotland, whiskey emerged organically out of the ingredients available—springwater, grains, the peat used to smoke the grain. Similarly, gin is processed using a variety of exotic ingredients from all over Europe that, in James Burrough’s day, would only be available in mass quantities in a major metropolis like London or Amsterdam. Of all the liquors out there, gin, like syphilis and Shakespeare’s plays, owes the most to the modern city.

James Burrough was equipped to experiment in the strange sorcery of gin making. Like the early fathers of distillation, who saw liquor as a cure-all medicine, Burrough was a pharmacist. By the time he founded his distillery, he’d trained as a chemist’s assistant in Exeter and worked as a pharmacist in Canada for six years. During his training, he’d already experimented with all kinds of strange alcoholic concoctions. He kept a diary containing recipes for bizarre drinks like English champagne and something called “artificial asses’ milk.” (The name alone makes the mouth water.) He’d created a pre-Prozac potion called “Sir Henry Halford’s Recipe for Nervous People,” which was probably heavy on the liquor, a substance that reduces inhibitions and tends to keep the hands from shaking.

But Burrough’s real love was gin. His dream: to create the finest in London—a tough task, considering that the local competition at the time included guys like Charles Tanqueray and Alexander Gordon of Gordon’s London Dry Gin fame. (The fact that you can go to a liquor store today and see these three sauces lined up next to each other on the shelf is simply awesome.) Burrough set up his operation right on the river Thames in the fashionable neighborhood of Chelsea, which was connected to downtown by King’s Road.

At the time, gin wasn’t the only game in town. Burrough distilled cordials too, such as blackberry brandy and rosemary liqueur. But gin was to be his bread and butter, and so he started experimenting. He kept a journal noting the different ratios of his concoctions. (That same dusty journal resides in the office of Beefeater’s current master distiller, one Desmond Payne.) Gin takes its curious flavor mainly from juniper berries, which were once thought to have healing properties and were used to treat hemorrhoids and worms. But there are any number of other ingredients, depending on the particular brand. After several trials and errors, Burrough finally nailed his recipe, a process of gin making almost identical to the one Beefeater uses today. In other words, if you take a sip of the stuff, you’ll be tasting a very similar liquor to the one that was dripping out of Burrough’s still nearly two centuries ago. While the exact ratios of ingredients have always remained a closely guarded secret, the process has not.

Beefeater creator, James Burrough. (Image courtesy of Allied Domecq)

First, Burrough made a neutral spirit, a liquor made of grain that comes out of the still “hot” and clear as water, similar to the way whiskey comes out of the still before it’s aged in oak barrels, or vodka, or any grain alcohol for that matter. Then he dumped the liquid back into the still again. But before he lit the fire under it, the spirit was left to steep with other ingredients—mainly juniper berries from Italy, with dashes of citrus peels from Spain, almonds and coriander from Russia and Eastern Europe, and angelica root from the fields of Belgium. Twenty-four hours later, Burrough lit the fire again, heating the liquid so that the alcoholic vapor rose up out of the vat and into the copper tubing, drawing the botanicals’ unique flavors with it as it trickled back out the other side.

Once satisfied with the flavor, Burrough turned to his next task. He had to come up with a name.

“A very large ration of beef is given to the warders of the Tower of London daily at court, and they might be called Beef-eaters.”

So the famous quote goes. The year was 1669 and the grand duke of Tuscany was describing the hefty yeoman warders who had guarded the palace of William the Conqueror. William, the bastard son of the duke of Normandy, had conquered the Anglo-Saxons in 1066. During his twenty-one-year reign, William built the infamous Tower of London, just down the Thames from where James Burrough would later open his distillery. Outside the tower, the Conqueror stationed his guards. He dressed them up in a bizarre outfit, the very one that’s depicted on the Beefeater gin bottle. These guards were paid in part with huge hunks of beef, to keep them portly and strong.

So there they stood, big guys whose job it was to hang out by a door and make sure the wrong kind of fellow didn’t get inside. In other words, the guy on the Beefeater bottle is the forefather of that most fascinating and valuable of modern tradesmen: the barroom bouncer. They don’t wear tights and velvet jackets these days. But goddamn it, they should.

To James Burrough, the name “beefeater” was a match. It symbolized the strength of his liquor—both in flavor and proof—and the history of London’s greatness. In no time, sophisticated drinkers were muttering, “Beefeater,” in restaurants all over the city.

For the rest of his life, James Burrough watched his gin business snowball. Late in the century, he handed the firm down to his two sons, Frederick and Ernest. By 1908, Beefeater outgrew the original Chelsea distillery, so they moved to a larger joint across the Thames in Lambeth. But the growth was just beginning. America was about to discover gin.

Up until this time, sloe gin had been available in the States; this strong-flavored liquor was brandy-based and flavored with sloe berries, the fruit of the blackthorn bush. The original Martini (the “Martinez Cocktail”) called for sloe gin. But during World War I, U.S. servicemen got a taste of what our allies across the pond were drinking. After that, Beefeater’s export market exploded. Bartenders in America soon started mixing Martinis with London dry gin, which didn’t exactly hurt Beefeater sales.

Growth continued under the leadership of a third Burrough generation. Alan Burrough, who died in August 2002, was a one-legged phenomenon. (He’d had the other leg blown off in Africa during World War II.) He oversaw Beefeater as the liquor became the brand of choice for more and more gin drinkers. By the 1960s, it was the bestselling London dry gin in the world, accounting for more than half of England’s gin exports. Today, it’s number two, behind Gordon’s.

These days, Beefeater is the only London dry gin that’s still in fact compounded in London. The liquor’s sold in 170 nations across the globe.

The success is partly due to good marketing. Who can ignore that idiot dressed up like a circus clown in tights, the prototype of the barroom bouncer, on the bottle? But Beefeater is also quite simply a fantastic gin. And there you have it: great liquor and imaginative marketing, mixed up in a glass. A perfect marriage.

MARTINI NATION

No cocktail in history has inspired such spirited debate and utter devotion as the Martini—that shimmering beauty of a libation, that glorious bowl full of diamonds. The oft-intoxicated sage of Baltimore, H. L. Mencken, called it “the only American invention as perfect as the sonnet.” The author Bernard De Voto once declared the Martini “the supreme American gift to the world.” (De Voto clearly forgot about the rubber chicken, which made its debut on a vaudeville stage in Newark, New Jersey, in 1911. But still, the Martini is a close second.)

Where did the Martini come from? Was there a bartender named Martini? A liquor purveyor? A notorious drunk?

Some scholars claim that the Martini was invented by an Italian bartender in New York named Martini di Arma di Taggia in 1912. Di Taggia claimed to have served one of his signature cocktails to John D. Rockefeller. Not the case. As the noted liquor writer Barnaby Conrad III pointed out in a Cigar Aficionado article, Rockefeller was a teetotaler. And how would one explain the ubiquity of Martinis in Jack London’s novel Burning Daylight, published two years before Di Taggia claimed to have invented the drink?

The Oxford English Dictionary claims that the Martini took its name from Martini & Rossi Vermouth back in 1894. This is also likely false.

The Martini’s provenance is probably much closer to Jack London’s hometown: San Francisco, the stomping ground of another famous bartender. “Professor” Jerry Thomas worked at the Occidental Hotel back in the 1860s. Apparently, he once mixed a drink for a gold miner who was on his way to the town of Martinez, a few miles east. Thomas recorded the “Martinez Cocktail” in his bartender’s manual, published in 1887. Though the drink wasn’t exactly a Martini, clearly it was a predecessor. It called for Old Tom gin, sweet red vermouth, dashes of bitters, gum syrup, and maraschino, chilled and garnished with a slice of lemon. The ratio was four to one. That’s four parts vermouth to one part gin.

The transition of this drink to the Martini we think of today happened slowly over the years. Old Tom gin (which was much more juniper flavored) was replaced by London dry gin. The red vermouth was replaced with dry white vermouth. The bitters were eventually abandoned. Some bartender had the bizarre idea of tossing a couple olives in there, and later cocktail onions (for a Gibson). Slowly the proportions went to equal parts gin to vermouth. Then to two-thirds gin. “By the thirties, you find the Stork Club pouring ’em at an entirely reasonable five parts gin to one vermouth,” notes the brilliant booze columnist David Wondrich, author of Esquire Drinks. “At the height of the Martini’s powers, in the gray-flannel-suit years, the ‘see-through’ went something like eight parts gin to no parts vermouth, with an olive.”

To this day, hard-core Martini fans can’t agree on how to make one. And it’s not just the proportions—it’s the way the drink is mixed. Shaken or stirred? Whole ice, shaved ice, crushed, or cracked?

“You see, the important thing is the rhythm [of the shake],” noted the detective Nick Charles in the film The Thin Man (1934). “You always have rhythm in your shaking. With a Manhattan you shake to fox trot time. A Bronx to two-step time. A dry Martini you always shake to waltz time.”

In the end, a Martini is whatever the hell you want it to be. Like a good set of tires, it’ll perform beautifully whether it’s dry (almost no vermouth), a little moist (a nice dash of the stuff), or soaked (equal parts). The only problem is communicating your exact preferences to a bartender. If you find one that makes a Martini to your liking, tip that barkeep nicely. When I was working at a particular fashion magazine years ago, my boss married a bartender. She fell in love with his pour, and the rest is history. (She was one tough broad. I imagine her bartender husband’s out there right now, muttering the famous Bogart line from Casablanca: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she had to walk into mine.”)

To wit, my Martini pour: three shots of gin with a half shot of vermouth, stirred with crushed ice and left to sit for a minute before it’s strained. Then I pour the concoction into a thin-stemmed Martini glass, which has been chilling all day in the freezer, naturally. A couple olives later (the big kind, with a drop of the juice), and it’s ready to drink.