The first thing you should know about the real Captain Morgan: he never made rum. Although the labels on some of the bottles bear dates from the seventeenth century, when the real Morgan lived, Captain Morgan’s Original Spiced Rum was actually launched by Seagram’s in 1983. The brand name is a marketing ploy, and a good one.

The real Captain Morgan lived a century before a “brand” of liquor ever existed. He lived during a time when rum—a distillate made from the dross of manufactured sugarcane—was just becoming popular among sailors and explorers, and he drank copious amounts of it. In fact, Sir Henry Morgan liked rum so much, he drank it until his skin and the whites of his eyes turned yellow. He drank until his liver swelled up fat and hard like a bowling ball, so his belly was distended so far over his sapphire-buckled belt that he couldn’t stand on his own two feet. The real Captain Morgan drank himself to death.

But before he did, Morgan lived a long life that makes for a tale as picaresque and hair-raising as any Hollywood script. If you judge by the picture of the smiley guy on the liquor bottle, you’d think he was a real swell guy, the kind of fellow who’d stop on the highway to help a stranger fix a flat tire. Hardly. The real Morgan was a privateer, a pirate captain licensed by the English monarchy to raid Spanish galleons and ports in the North Sea, as they called the Caribbean back then. Sailing from one sun-drenched island to the next, the swashbuckler slaughtered untold numbers of innocent and not-so-innocent people, torched entire cities, robbed from his own men, stole from priests and nuns, and changed the course of history forever.

By some accounts, he was a brutal rapist to boot. During his final years, Morgan got himself embroiled in a torrid sex scandal that’s shocking even by today’s standards. At the peak of his meteoric fame, the imbroglio sent him cascading off his pedestal into the quotidian hell of a London jail cell.

Nevertheless, by the time he died in 1688, Sir Henry Morgan had amassed an unfathomable fortune—huge caches of pilfered precious metals and jewels—not to mention a legendary status among centuries of salty dogs to come. All in all, he kept himself pretty busy, for a drunk.

Born in 1635 in the Welsh village of Llanrumney, Henry Morgan was raised near Cardiff, the capital of Wales. The stately family home where he was born still stands (it’s since been converted into the Llanrumney Hall Hotel, with a pub on the first floor). At age twelve, Morgan set off on his first expedition at sea, bound for Barbados. There are two theories as to why. Some claim he was kidnapped and sold off in the white-slave trade, while others believe he was escaping imprisonment for brawling and—more urgently perhaps—the wrath of the father of a young girl he’d deflowered.

At the time, Spain had claimed most of the New World in the West for herself. One hundred fifty years earlier, the Spanish king Ferdinand had sent Christopher Columbus to what they both thought was India. Columbus had sailed the wrong way and landed in the Caribbean Islands, and the Spanish colonists followed. By the time Henry Morgan was born, Spain had brought in more gold from the West than existed in all of Europe three times over. And there was plenty more to go around.

There were laws in the New World—laws meant to protect the Spanish ports and the galleons carting the gold back to the monarchy. There just wasn’t any way of enforcing them.

Spain’s archenemy, Britain, launched a fleet of ships to infiltrate the rich island outposts. Headed up by Admiral Oliver Cromwell, the fleet was the precursor to the Royal Navy. In 1654, young Henry Morgan escaped from his slave owner and enlisted. He was dispatched to attack the Spanish at Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti). An experienced seaman, boozer, and brawler, Morgan impressed his peers in the pitch of battle. But the British lost this one, and the fleet retreated to Jamaica, where they set up their home base.

Morgan would end up making Jamaica his home for the rest of his life. It was there that he and his cronies realized that the straight-on military attack approach might not be the best way to go about things. So they devised a new plan. The era of modern piracy was about to be born.

In the years to follow, the British fleet began attacking and looting poorly protected Spanish outposts, rather than going after the military, as was the custom. It was piracy, a barbaric approach with total disregard for law or morality. Naturally, it worked. The pirates began hauling in so much loot that, instead of punishing them, King Charles II of England awarded them licenses.

The British already controlled some of the smaller islands in the Caribbean, and they started to infiltrate more. (This accounts for the beer-battered fish and chips and bland meat pies you can order up today in Jamaica, Barbados, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, etc.) Meanwhile Morgan’s reputation as a fearless raider earned him the title of captain, and he began a reign of terror that would mark his legend to this day.

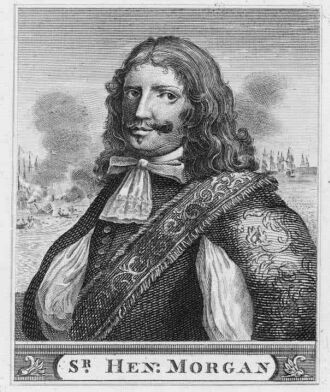

Dressed in the classic costume of the buccaneer—an embroidered crimson coat and matching hat, with long locks of dark hair and a handlebar mustache that would make Freddie Mercury green with envy—Morgan looked much like the swarthy caricature on today’s Captain Morgan rum bottle. According to portraits from the day, he had tanned leathery skin and dark executioner’s eyes, which were a little too far apart. As captain, he chose his first target: the Spanish port of Cumana in what is now Venezuela. The town was renowned for its rich collection of fine pearls.

With a fleet of ten ships and more than a thousand men armed with sabers, muskets, daggers, and crude bombs, the British raiders took the Spanish settlers by surprise. They looted the city, taking whatever they desired, and escaped with massive amounts of gold. Next they hit Puerto Cubello 250 miles to the west. After that, Morgan sailed the fleet 125 miles farther west to the tiny town of Cora. As his ships approached, the settlers ran for the hills, leading Morgan straight to the mother lode, hidden there far from town. He made off with twenty-two chests of silver marked for the king of Spain, then worth £375,000—an unprecedented score, the equivalent of millions today. It was enough to make Morgan rich for many lifetimes. But he wasn’t done yet.

Following the raid on Cora, Morgan made daring forays into what is now Cuba, Venezuela, and Haiti. One by one the ports fell: Providence, San Lorenzo, Venta La Cruz, Portobelo. At one point he sailed his fleet to a port in present-day Nicaragua, ventured up a river to a lake, and pillaged inland villages in the mountains. They were a fleet unlike any other at the time, driven by greed rather than patriotism.

In 1671, Morgan was promoted to admiral of all British warships in the Caribbean. He had a group of thirty-six vessels and more than two thousand men. He was known to torture local islanders until they gave up the hiding places of their gold. He held entire cities ransom and threatened to set them ablaze until the locals coughed up everything. He was recognized wherever he went—the most feared man in the Caribbean.

Captain Henry Morgan (1635–88). (Image courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library, London)

When he wasn’t at sea, Morgan spent lavishly at taverns near his home in Jamaica, where he drank copious amounts of the local sauce—a clear crude rum that would likely repulse the palate of today’s drinker.

Among other things, the Spanish colonists Morgan had been robbing had brought sugarcane to the Caribbean, which proved to have a perfect climate for the tall grass. Sugar was in great demand in Europe. A shortage of honey and the increased taste for sweetness among the upper classes (lemonade was invented in Paris in the 1630s) created an urgent demand for cheap crystallized sugar. By Morgan’s time, cane plantations had popped up all over the islands, where they remain today. When the tall, thick cane grass was processed into crystallized sugar, molasses was left over. Clever sugar processors began experimenting with the molasses to see if they could make something useful out of it. When they added yeast and water, the molasses fermented. Eventually, some English subjects had the idea of distilling the fermentation the way whiskey was distilled back home. They called the liquor Kill Devil (because it was a cure for disease; it killed the devil in you) or Red-eye (it gave you a nasty hangover). Others called it rumbullion (from the English words “rumbustious” and “rumpus” because it made some drinkers violent—sometimes violently ill).

RUM DECONSTRUCTED

Few liquors are as misunderstood as rum—the drink of pirates, navy men, and frat boys alike. There’s good reason. For one, distilling regulations vary from island to island throughout the Caribbean. So unless you’ve done your homework, it’s tough to know what you’re drinking. The languages spoken among producers vary as well. You can buy Caribe rum with labels written in English, Spanish, and French. The liquor might be called rum, rhum, or even ron. This much is consistent: the liquor is distilled out of either pure sugarcane juice or molasses (what’s left over after sugar is extracted from cane) and is generally bottled somewhere around 80 proof, unless it’s “over proof” rum. The following will get you a grip on the bottle so you can pour accordingly.

WHITE RUM: The “see through” rum that resembles water—also sometimes called White, Clear, Crystal, Cristal, Silver, Blanc, and Blanco—is rum that’s bottled young, aged either not at all or up to a year or two. White rum is usually the cheapest and not surprisingly the most popular of rum varieties. It’s great for mixing. Example: Castillo Silver Puerto Rican Rum.

REGULAR RUM: Usually aged from one to three years, this rum will have an amber or copper color, a result of contact with the wood in a barrel. Caramel may also be added to enhance the color. Most regular rums (also sometimes called Gold or Oro) are good enough to drink on their own with a little ice, but they’re also great for mixing—say, with tonic and a lime wedge. Example: Mount Gay Refined Eclipse Barbados Rum.

PREMIUM RUM: Generally speaking, this is a rum that’s been aged for three years or more, also known as rhum vieux or ron anejo. Some premium rums are aged as long as fifteen years. Like a cognac or a fine single-malt Scotch, it can be sipped out of a snifter. Example: Ron Matusalem Gran Reserva.

OVER PROOF RUM: “Over proof” generally connotes any rum that’s bottled at 51 percent alcohol or stronger (including the “151” that some producers market). It’s usually white, and it’ll jackhammer your liver if you’re not mixing it. Example: Bacardi 151 (“Warning: Flammable”).

DARK RUM: Also known as black rum, this stuff pours out of the bottle thick and tarlike. The color and viscous consistency is a result of the blending and aging process. Because it has a rich syrupy flavor, it’s often mixed with other rums to give a cocktail (a Mai Tai, perhaps) an added touch of character and sweetness. Examples: Myer’s Jamaican Rum and Gosling’s Black Seal Rum.

SPICED AND FLAVORED RUMS: Like vodka, a rum’s flavor can be infused with just about anything—orange, banana, coconut, pineapple, passion fruit, spices, coffee, even peanuts. Some folks dig it. But some think spiced and flavored rums are a bit silly—a mockery, a travesty, a sham even. My advice is to confront the issue case by case, bottle by bottle. Examples: Captain Morgan’s Original Spiced Rum and Malibu.

One published island diary that dates back to 1651, Cavaliers and Roundheads Barbados by N. D. Davis, had the following description: “The chief fudling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugarcanes distilled—a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor.” Another contemporaneous diary describes rum as a dangerous beverage that could “overpower the senses with a single whiff.”

A plague of drunkenness spread among seamen who were far from home, men who had pockets full of stolen gold, no family in sight, and plenty of time on their hands. Jamaica’s Port Royal—once a lonely island outpost where Morgan and his men suffered through pestilence and ate dogs, rats, and snakes—became known as the “Port of Orgies,” the most sinful and licentious city in the world. In the taverns, drunken sailors engaged in violent swordplay, sometimes wounding and killing each other in the name of amusement. Female African slaves who’d been imported to work the sugarcane plantations were made to dance, strip, and submit themselves on the tables and on the floor while others watched. Establishments were sometimes burned to the ground during a night’s partying.

Among the island colonists, Captain Morgan was notorious for his ability to consume rum without showing any effect. Though by this time he’d married a Welshwoman, he enjoyed pleasures of the flesh like the others as well—though according to one biographer, he never fornicated in public. His ambition for drink grew to equal his ambition for piracy on the high seas. Eventually, his ambition would get the better of him.

In 1671, Panama City held the greatest cache of silver and gold in the world. Guarded with great resource, the precious metals had been smelted into coinage to get carted by galleons back to the king in Spain. The port was protected behind fortress walls. To attempt to steal the fortune would be suicidal.

Leading a massive gang of more than a thousand starving and hungover buccaneers (they’d had a terrible bout with some Peruvian wine they’d stolen two days before), Captain Morgan, then thirty-five years of age, landed on the isthmus of Panama in January and headed for the gated city of seven thousand Spanish settlers. The city’s port was a silty river that dropped some twenty feet during low tide, and Morgan had already lost one ship—the Satisfaction—on a reef during the voyage. So the pirates landed at the village of Cruz de Juan Gallego and marched the rest of the way on foot, clearing thick jungle with machetes. Tribes of savages armed with bows and arrows greeted them. The Brits battled their way toward the city, scaring off the local warriors with explosive muskets, until they reached a hilltop that overlooked their destination.

There in the hills, they found livestock grazing. They hadn’t eaten, they were brutally hungover, and they were about to go to battle. While some began slaughtering cows, horses, and donkeys, others busied themselves building fires to roast them. One pirate who was present later wrote:

They devoured [the livestock] with incredible haste and appetite. For such was their hunger, that they more resembled cannibals than Europeans at this banquet, the blood many times running down from their beards unto the middle of their bodies.

Below them, Panama City was laid out in a north-south/east-west grid. The city consisted of seven monasteries, numerous churches and convents, a hospital, and a courthouse. The streets were lined with homes made of sunbaked timber, which burned easily. The Spanish had received word of Morgan’s arrival; a vanguard of 2,100 Spanish, African, and native soldiers with six hundred horses was preparing to fight off the British intruders. But it wasn’t enough.

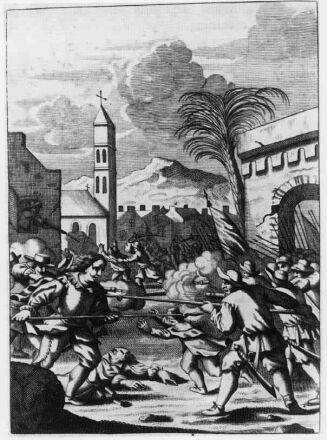

On a hot and sunny Sunday morning, Morgan attacked, and the clash turned into an inner-city riot. Citizens and military alike used anything they could get their hands on as weapons. The British sacked the city in a matter of hours. They slaughtered untold numbers, took three thousand prisoners, and then set the place ablaze.

By midnight, Panama City “was all consumed that might be called a city,” Captain Morgan wrote in his diary. “Thus was consumed that famous and ancient City of Panama, which is the greatest mart for silver and gold in the whole world.”

As the streets burned, the pirates turned their attention to their appetites, the kind men have when they’ve been at sea too long. One witness present—a buccaneer named John Esquemeling, who later published stories about Morgan’s raids—described pirates raping scores of women in the streets in front of their terrorized families. The witness recounted one specific incident regarding Morgan himself.

The captain allegedly captured the wife of a rich merchant, a beautiful and virtuous woman. He cornered her, and according to Esquemeling, who claimed to have been within earshot of the incident, she begged him to kill her rather than rape her.

“Sir,” she pleaded, “my life is in your hands; but, as to my body in relation to that which you persuade me unto, my soul shall sooner be separated from it, through the violence of your arms. . . .”

According to the witness, Morgan then ravaged her: “He used all the means he could both of rigour and mildness to bend her to his lascivious will and pleasure.”

Morgan looted Panama City for a total of twenty days, then absconded with literally boatloads of loot. Little did he know, the kings of Spain and Britain had just signed a peace agreement back in Europe. Even had they not, Morgan’s murderous assault was excessive. Just forty-four days after the raid, a broadside hit the streets of London detailing the shocking fall of Panama City. News of the sexual exploits followed, courtesy of John Esquemeling. If Morgan went unpunished, the Spanish were prepared to form an army of five thousand men to sail on thirty-six ships, intending to capture Jamaica from the English at all costs.

Charles II immediately declared martial law in Jamaica, and within weeks, Captain Morgan was arrested and brought back across the Atlantic in chains. A long investigation ensued, during which time Morgan was the subject of public consternation and ridicule. He was humiliated—Bill Clinton–style.

Morgan Sacks the Town of El Puerto Del Principe. (Image courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library, London)

Luckily for Morgan, Charles II was himself an accomplished sailor and carouser. It appears that Morgan and the king boozed it up good and hard together during the captain’s prison term. Morgan, in turn, sued Esquemeling for accusing him in print of rape and other crimes. He ended up winning the case, the first ever libel court case of its kind.

After two years, the buccaneer was exonerated, sent back to Jamaica, and awarded lieutenant governorship of the island. He was later knighted. His legend made, the cloud of controversy burned away under the hot Caribbean sun, and he had nothing left to do but drink himself to death.

For the next fifteen years, Morgan spent his days heading from tavern to tavern, boasting of his exploits and making new enemies. The drunker he got, the more bizarre were his antics. On May 14, 1682, he was removed from his post as lieutenant governor for his consistent “irregularities.”

As the pirate moved into his fifties, his health started to decline. In April of Morgan’s final year, one Dr. Sloane came to see him and wrote in his notes that the captain looked “lean, sallow-coloured, his eyes a little yellowish and belly jutting out. He had a kicking or roaching to vomit every morning.” The culprit, Sloane gathered: “drinking and staying up late.”

The doctor urged temperance, and Morgan improved when he stopped drinking. But he couldn’t control himself for long. In his final months, his legs started to swell (a symptom of the liver disorder gout), and his gut followed. Eventually, his liver ballooned. He was in such pain he could barely move from the hammock on the veranda of his mansion in Jamaica’s Port Maria.

At eleven in the morning on August 25, 1688, the buccaneer died at the age of fifty-three. His bowels were removed and buried beneath the altar of the church in Spanish Town. (It must’ve seemed like a good idea at the time.) The rest of his body was sent back to Wales for burial.

A shady dealer, Morgan left behind more than a reputation as a drunken pirate king. On a number of his brutal raids, he made off with large amounts of booty and afterward refused to pay his men their full share of the loot. Or so his buccaneers suspected. Whether this is true or not, the man brought in an enormous fortune during his lifetime. In the lawless islands, banks were dubious, and they didn’t issue checks or ATM cards. If you had in your possession enough stolen goods to fill up the Coliseum in Rome, you had to figure out a place to stash it. So what happened to Morgan’s loot?

There’s evidence to believe that he hid a large quantity of gold and silver in caves near his plantation in Jamaica and in Cayo Zapatillas in Panama, as well as back in Wales near where he was born. Any number of expeditions have been launched over the centuries to gather the loot. None of it has ever been found.

THE SKINNY ON CAPTAIN MORGAN’S RUM

The Captain Morgan Rum Company was founded in 1943, and was later purchased by Seagram’s.

Captain Morgan is second in rum sales in the world, behind Bacardi.

Drinkers consume about thirty-five million bottles of Captain Morgan’s rum annually.

The brand is now owned by Diageo, the liquor behemoth that also owns Smirnoff, Guinness, Baileys, Johnnie Walker, and a host of other tasty beverages.

The rum is produced at the Distileria Serralles in Puerto Rico, though the Captain Morgan rum that’s drunk outside the U.S. is produced in Jamaica.

There are five Captain Morgan spiced rums currently on shelves, aimed at different rum categories: Silver Spiced (white rum), Original Spiced (regular rum), Black Label (dark rum), Private Stock (premium rum), Parrot Bay Coconut (flavored rum).

However, in 1999, a crew from an underwater documentary company out of Halifax, Canada, was filming on a shipwreck off the coast of Haiti when they came across the ruins of another boat under just six feet of seawater. After investigating the wreck and checking archaic records back in Britain, the crew learned that the ship was in fact the Merchant Jamaica. It was Sir Henry Morgan’s boat—the only seventeenth-century pirate ship ever to be found.

According to records, the Merchant Jamaica struck a reef while sailing along Haiti’s southwestern coast in the 1670s. The ship broke apart in the shallows. Eighteen men perished, but Morgan survived and kept notes on what happened. He later returned to retrieve twenty cannons (nine remain with the wreck).

“We have already found the anchor and the cannons and a few pieces of porcelain and some bronze coins,” Monika Wetzke, a spokesperson for the expedition, told a newspaper in Morgan’s native Wales. “We haven’t found any bodies.”

Or any loot either. Whatever Morgan had up his sleeve, it’s still out there—a modern-day pirate’s treasure so huge it could only be equaled by, say, a brilliantly marketed brand of liquor that sells some thirty-five million bottles a year. As they say at sea, down the hatch.