According to one of the greatest myths in the long intoxicating history of booze, champagne was discovered on a fall day some three hundred–plus years ago. In his dank cellar, a blind monk stood tasting a vintage he’d made from grapes picked at different locations around his vineyard in the northern plains of France. Renowned for his eccentric winemaking methods, the blind monk had mixed the different grape bunches like a mad scientist, suffering over the choice of each single ball of fruit. When he scooped some of the potion out of a barrel to inspect it, the wine frothed out of his goblet. He lifted it to his lips and tasted, then cried out to his fellow monks as if he’d just touched the hand of God.

“Come, brothers, hurry!” he shouted. “I am drinking stars!”

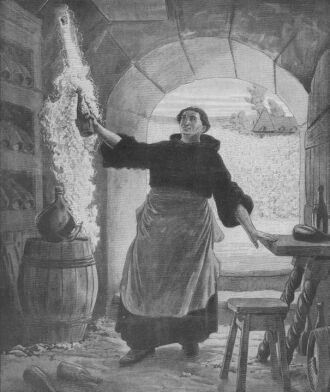

The stars, of course, were bubbles of carbon gas in the wine. And the vintner’s name was Dom Perignon. Artists have since rendered the winemaker in the typical garb of the Benedictine monk: a long black robe with a large pointed hood, the monk’s head tonsured, leaving a halolike ring of hair. He’s holding a goblet of glowing golden liquid, which is boiling up out of the cup like a geyser. Perignon’s face is clouded by bewilderment, as if he is completely loaded on the stuff.

Of course, you’d have to be loaded yourself to believe this myth is entirely true. Sparkling wine had existed for centuries before Dom Perignon was born. Evidence suggests that the Romans, who first brought viticulture to the Champagne region of France, had experienced the bubbly buzz of sparkling wine. Even the Bible speaks of wine that “moveth.”

But Dom Perignon is credited for the discovery to this day, because in the monk’s time, a sparkle of carbon gas was considered a fault in a wine. Froth belonged to beer, the drink of the English. Bubbles were considered vulgar, a sign that the grapes used to make the wine weren’t quite ripe yet. But by Dom Perignon’s death in the year 1715, sparkling wine from his vineyard at the Abbey de Hautvillers was the preferred beverage for the finest tables throughout Europe. By the time Perignon died, according to the diaries of his protégé, Brother Pierre, the French had developed an absolute “mania” for his sparkling wine. “The Reverend Father Perignon achieved the glory of giving the wines of Hautvillers the high reputation they enjoy from Pole to Pole,” Pierre wrote.

Dom Perignon discovering champagne. (Image courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library, London)

Perignon’s eternal fame was secured. He had created a magical wine, rich with effervescent perfection. The wine tasted so good you could sip it right out of a lady’s slipper (which, centuries before the shower was invented, must have been quite a feat). Today, the drink is still the toast of dignitaries the world over, from James Bond to Queen Elizabeth. Currently, it’s the only wine sold at Hooters restaurants: the “Gourmet Chicken Wing Dinner,” twenty wings and a bottle of Dom for $148.88. What an honor.

(Here’s another honor worth mentioning, as a short aside: Years ago, on May 30, 1976, this writer got his first drunk on with a bottle of Dom. I was five years old, a few years younger than the vintage itself. It was my parents’ tenth wedding anniversary, and they’d celebrated with a couple ceremonial bottles. The next day, I found a half bottle left in the refrigerator and drank it like it was grape juice, which of course it was. Hours later, my mother was ready to take me to the emergency room. She thought I had a brain tumor, the poor lady. Then she found the empty bottle I’d hidden behind the couch.)

The sparkle in the champagne and the very sweet buzz it generously smears on the soul are just a couple of Dom Perignon’s winemaking achievements. In a mouthful, this monk is almost single-handedly responsible for turning wine from the crude drink of the Dark Ages into what we now drink today: a heady fermentation of grapes aged in a labeled bottle, made airtight with a chunk of cork tied on top. Perignon was very likely the greatest winemaker in the history of viticulture, a history that lasts as long as civilized humankind itself.

Pierre Perignon was born in the parish of Ste. Menehould in the Champagne region of France; he was baptized in the church there on January 5, 1639. It was a quaint, sparsely settled area ninety miles to the west of Paris, speckled with sheep farms and vineyards. When they first brought winemaking to the region, the Romans called the place campus, which meant “field,” adequately describing the region’s flatness. The Gauls later changed the name to Champagne. The soil in the region was rich in chalk and minerals, the remnants of an ancient sea that once covered Europe. By the time Pierre Perignon was born, the land was also rich with the blood of dead Frenchmen. Everyone from Attila the Hun to marauding hooligan Brits had swept through, slaughtering and pillaging with apparent glee. Some say you can still taste the blood salt in the wine grown in Champagne.

Perignon enjoyed a bourgeois upbringing. His father was a judge’s clerk who married rich. The boy’s future was apparently made. But in the spring of 1657, Perignon swore off his earthly belongings, signed away his inheritance, and entered the monastery of St. Vanne at nearby Verdun.

By any respectable standard, you’d have to be a half-wit to join the order of St. Benedict. Perignon rose at two A.M. The day consisted of nine hours of prayer, seven hours of manual labor, and two hours set aside for reading. He slept in a tiny ten-by-nine-foot room, sans any of the beautiful women who, wine aside, have always been France’s greatest export.

The monks had just one indulgence: winemaking. Since the Middle Ages, they had been the chief viticulturists in Europe. The fermented grape juice was used in ritual ceremony and, more important, was sold for profit. Wine selling was the monks’ chief source of income. It paid the bills.

In 1668, at the age of twenty-eight, Perignon was sent to the Abbey of Hautvillers, a few days’ journey through the countryside, where he would be procureur. In today’s terms, procureur was CEO, drill sergeant, boss man, and resident ass kicker. He was basically in charge of everything. Some eighty years earlier, Hautvillers had been raided and wrecked in the name of God by Protestants. The Abbey was in shambles. Perignon was put in charge of repairing it to its original grandeur—no easy job, especially for a man not yet thirty years old. With plenty of local laborers and monks under his charge, he had the manpower. He had all the time in the world. He was missing one thing: cash.

Money for Perignon literally grew on trees. Or vines, at least. So in order to make some cash, he set about restoring the Abbey’s vineyard first.

Generally speaking, most of the wine produced in Champagne at the time was regarded as swill. Burgundy to the near south produced the good stuff: wines that had a reputation outside the village where they were made. Unlike Burgundy’s, Champagne’s cooler climate tended to kill off a year’s harvest early, so the grapes had to be picked before they were completely ripe. The monks used both red and white grapes—very likely pinot noir, pinot meunier, and chardonnay, the same grapes used in today’s champagne. The red ones were picked before the skins could gain a strong pigmentation, so the juice they produced was cloudy and straw-colored. The wine was known as vin gris (gray wine). Often it was spiked with brandy to keep it from turning to vinegar before it was drunk.

Perignon’s first innovation was to create a winepress that squeezed the juice from the fruit more swiftly. The machine forced the juice from the skins before any of the red pigmentation could seep into it. The result: the first truly white still wine made from red grapes.

In the fields, Perignon urged extreme precision in inspecting and harvesting his grapes. As with most geniuses, he would today be regarded as an incredible tight ass, very likely detested by his field hands. Winemakers at the time planted nearly eight thousand vines to the hectare (2.2 acres). Perignon planted five thousand. Field laborers were hired for the equivalent of a few pennies, a loaf of bread, and three chopines of wine (literally, three woman’s shoes full) per day. Laborers were forbidden to consume a single grape and were never allowed to eat their bread in the fields, “lest their crumbs get in the wine.”

Once, the monk caught a field worker stealing a handful of grape vines. The thief was branded on both arms and sentenced to nine years’ hard labor.

Perignon’s second brilliant winemaking innovation was to mix grapes from different areas in his vineyard, giving rise to the idea of the cuvée. Blending wines was unheard of at this time. You just took all your grapes and pressed the hell out of them. The idea of the cuvée (literally, a large vat used for fermentation) meant that you could blend your best grapes from different areas to make the finest wine possible—the cuvée par excellence, “destined for the tables of the greatest princes in Europe,” in the monk’s words. Then you could make another grade to sell to locals on the cheap, and then finally a batch of swill with which you could pay your workers. This method allowed the maker to control the quality and consistency of the product, not to mention increase profit. (Today’s finer viticulturists do the same. That’s one reason why you can buy six different 1999 cabernet sauvignons from Mondavi, with prices ranging from $30 to $125.)

During harvest season in the fall, Perignon had his laborers deliver him samples of grapes in wicker baskets from different areas of his vineyard, which spread out across roughly one hundred acres. The monk set the grapes on the windowsill overnight and tasted them in the morning before he ate breakfast. According to his protégé, Brother Pierre, he would then decide on his blends, “not only according to the flavor of the juice, but also according to what the weather had been like that year—an early or late development, depending on the amount of cold or rain there had been—and according to whether the vines had grown a rich or mediocre foliage.”

Gradually, Perignon gained quite a reputation. The more wine from Hautvillers flowed on tables all over France, the more cash began to flow in. Like a sharp entrepreneur, the monk dumped his money back into the vineyard. Slowly, Hautvillers began to take over the countryside. Perignon built a cellar that could accommodate five hundred barrels of aging wine. The stage was set for his ultimate innovation—one that he would stumble onto by mistake.

According to the legend of Dom Perignon, two traveling monks from Spain en route to Sweden stopped for a respite at Hautvillers one day. Perignon noticed that the Spaniards kept their water in gourds that were stopped by a squishy wooden substance, the likes of which the Frenchman had never seen. The wood was soft, so it could be squeezed and shoved in a small hole, where it would then expand to make the hole airtight. The substance, which the Spaniards called cork, kept their drinking water clean and prevented it from spilling as they were dragged by donkeys for hundreds of miles over bumpy terrain on wooden wheels.

Perignon requested samples of cork from Spain. At this moment, as Richard Fetter points out in his perceptive biography Dom Perignon: Man and Myth, the wine export business was born.

Until that time, wine in France was transported in casks. When purchased, it was decanted into fragile bottles and stopped with whittled wood chunks tied down with hemp. Consumers were left with bottles that broke easily and wine that spilled during transportation. Since the bottles weren’t airtight, the wine turned to vinegar if it wasn’t drunk within a couple weeks.

With corked bottles, wine could be shipped more easily. It could be sent as a finished product throughout Europe and sold to consumers, who wouldn’t have to lug around their own bottles. Following Dom Perignon’s lead, winemakers all over Europe began bottling their wine, melting wax over their corks to ensure the bottle was genuine, and branding a symbol in the hot wax, the precursor of the wine label. Perignon’s symbol was a cross.

There was just one problem. Vintners began to notice that, while their wine aged in bottles, the glass tended to explode. They were bottling the juice before the fermentation process was complete, so the liquid was producing bubbles of carbon gas that, in an airtight bottle as opposed to a wooden cask, had no escape. Kaboom! According to records dug up in Hautvillers, 1560 out of 2381 bottles exploded one year in Perignon’s cellar. Glass shattered to shards and flakes, and the fruit flies swarmed in. . . . In today’s parlance, it would be called a complete fucking mess.

To solve the problem, winemakers began aging their product longer in casks before bottling it. But Perignon, in contrast, took a different route. He began using verre anglais—bottles blown from a new, much stronger glass made with technology imported from London. If the wine was bottled at just the right time, the glass was strong enough to prevent explosions during the fermentation process. In order to collect the sediment in the neck, the bottles were aged upside down, stuck neck down in some sand. When one was opened, the carbonic gas would make the cork pop like a musket shot, and the aged wine would then bubble over.

“Du Champagne, Avec un Coup de Poing, Monsieur?”

Champagne can be a riddle. Here’s a little guide to help you read the label.

GRAND CRU: Champagne made from grapes considered to be of the highest quality (i.e., with a rating of 100 out of 100). Of the nearly three hundred villages in the Champagne region, only seventeen have grand cru ratings. In other words, this is some of the finest wine on the planet.

PREMIER CRU: The next level down from grand cru, this wine is made from grapes grown in villages that have ratings of 90–99. Expect to spend a bundle and to drink a fine bottle.

CUVE: The blend. Champagnes today might be a blend of twenty, thirty, even forty different wines.

VINTAGE CHAMPAGNES: A champagne is considered vintage if the head dude at the champagne house feels that the grapes harvested that year are of superior quality. Vintage champagne must be aged at least three years before drinking, though it’s often aged much longer.

NONVINTAGE: Three-quarters of the champagne produced is nonvintage. In other words, here’s your everyday, deliciously rich sparkling wine. A nonvintage champagne must be aged at least two years prior to drinking.

ROSE: Pink bubbly—great for Valentine’s Day and anniversary dinners—has a dash of red wine or red grape skin added into the mix, to darken the color. It’s generally full-bodied.

BLANC DE NOIRS: Most champagne is made with pinot noir, pinot meunier, and chardonnay grapes. This slightly pinkish champagne has no chardonnay.

BLANC DE BLANCS: A lighter sparkling wine made exclusively of chardonnay grapes.

BRUT: Dry. A brut wine will have less than 1.5 percent sugar in it.

EXTRA SEC OR EXTRA DRY: Basically the same as brut, though perhaps a tiny bit sweeter.

DEMI-SEC: A sweet champagne, with up to 5 percent sugar.

DOUX: A sweet wine with more than 5 percent sugar. (Doux and demi-sec are considered dessert wines.)

CUVE DE PRESTIGE OR CUVÉE SPECIALE: The crème de la crème of champagne brands. Moët & Chandon’s Dom Perignon was the first to use this term. Others today include Grand Cuvée from Krug, Belle Epoque from Perrier-Jouët, and Cristal from Louis Roederer.

Champagne as we know it was born.

The official year given to the first vintage was 1690, when Dom Perignon was fifty-one years old. Bottles still sometimes exploded, which drove up the price of the ones that didn’t. Still, the stuff took off on the burgeoning wine market among customers who could afford it (thus the high-end clientele that champagne has always enjoyed). Within four years, the king of France himself, Louis XIV, had ordered his share of Dom Perignon’s wine. A bottle was selling for five times the price of other regional wines. Champagne was here to stay, and the legend of Dom Perignon was made.

Not long after, the king of France made a law stipulating the exact size and shape of the bottle, which is pretty similar to the Dom Perignon bottle now in stores. It must weigh twenty-five ounces, the king proclaimed. It must contain one Paris pint (1.6 pints), and be tied down with three-threaded string twisted and knotted in the form of a cross over the cork. Voilà! Champagne.

For the rest of his life, the monk worked to perfect the process of making bubbly. According to some accounts, he went blind during these years. (Surely this had nothing to do with all the homemade booze he was drinking.) Nevertheless, his skill in making wine with bubbles increased until the end. It was in essence a guessing game. “The great art of making champagne consists in seizing the moment when the wine in cask has neither more nor less of the quantity of sugar needed to give an excellent mousse [froth] and yet not break the bottles,” explained one nineteenth-century wine historian.

By the time Dom Perignon died in 1715, his name was as famous as any in France. He was one of only two monks ever to be buried in the choir of the church at the Abbey de Hautvillers. There his gravestone bears this epitaph:

Here lies

Dom Pierre Perignon

For 47 years

Cellarer of this monastery, who

Having administered the affairs

Of our community

With praiseworthy care,

Full of virtue

Above all in his fatherly love

For the poor

Died

At the age of 77

In 1715

Rest In Peace

So how did the brand of Dom Perignon come to be? Not surprisingly, the Dom Perignon you can buy today has nothing to do with the monk, aside from the fact that he is credited with the “discovery” of champagne.

The year was 1932. Alcohol was illegal in the United States when the brand was first launched. In Europe, the wine market was getting spanked, a casualty of the worldwide Great Depression. In order to stimulate sales, the folks at the esteemed champagne house Moët & Chandon decided to produce a cuvée of the finest sparkling wine and name it after the great monk. Three years later, the company sent gift baskets to one hundred fifty of its best clients, mostly English aristocracy, containing two bottles of this rare champagne. The label, almost identical to the one produced today, featured wild grape vines, a big green star, and the name Cuvée Dom Perignon across it in delicate script. The vintage was 1921. If you were to stumble across one of these bottles today, it would be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Word of the fabulous bubbly quickly spread across the Atlantic. With Americans drunk with glee over the repeal of Prohibition, a great demand for the fabled champagne grew in New York City. So in November 1936, Moët & Chandon sent the first shipment of one hundred cases of the 1921 vintage by boat to America. By New Year’s Eve of that year, a select few in the New World were getting sloshed on the finest sparkling wine ever produced anywhere in the world.

The vintages of Dom available today are still of extraordinary quality by most experts’ opinion. By law, champagne must be from the Champagne region of France and aged at least fifteen months. (Otherwise the drink is just called “sparkling wine”.) Unlike in Dom Perignon’s day, when the wine’s bubbles were a result of the fact that the juice was still fermenting when it was bottled, today’s champagne is bottled completely fermented. A dash of sugar is then added to the still wine before corking—touching off a “second fermentation”—to give the stuff its trademark effervescence.

By the way, a bottle of champagne off the shelf contains roughly forty-nine million little bubbles (yes, someone actually took the time to count). And the taste? France exported 262.6 million bottles in 2001, so they must be doing something right. The unique drink has never lost its luster after all these centuries. Spend a sunset with a bottle and a chilled Maine lobster or some delicate oysters with just a drop of lemon or a peanut butter sandwich, if that kind of thing turns you on. Affording a bottle of bubbly is half the pleasure.