“Goddamn! Hell! We’re gonna be late!” cries seventy-three-year-old Booker “Hard Times” Noe, the master distiller emeritus of Jim Beam’s stable of whiskeys, his giant body shoehorned into the front passenger’s seat of a sea green Ford minivan.

“Do you want to put your seat belt on?” asks the driver, a young, dark-haired guy named Jim.

“I don’t mind if you can manage to get the thing around me,” Booker replies in his trademark deep Kentucky drawl. Jim gives the old man’s six-foot-four-inch frame the once-over (Booker looks like he’s just swallowed a bourbon barrel whole), ponders for about three seconds, then throws the car in gear and hits the gas. We’re headed from the main Jim Beam distillery in Clermont, Kentucky, fifty miles away to Wild Turkey in Lawrenceburg, where a ceremony will be held to induct, among nine others, the original Jim Beam into the Bourbon Hall of Fame. Booker will be accepting the award in honor of his grandfather. (The so-called Bourbon Hall of Fame is just a couple years old. Like a lot of things in these parts, it’s basically an excuse to indulge in a Kentucky double feature: whiskey and ham.)

Slowly the minivan pulls down the road past the Beam distillery on the right: a massive operation of pipes slithering like petrified snakes out of the ground with giant stacks blowing smoke and trucks loading up with cases upon cases of some of the finest bourbon in Kentucky. The stink of mash fermenting assaults the nose. To the left, towering corrugated metal rack houses hold thousands of fifty-three-gallon five-hundred-pound barrels of Beam whiskey: Jim Beam White Label, Jim Beam Black, plus the company’s four “small batch” bottlings (Basil Hayden, Baker’s, Knob Creek, and Booker’s). In the front seat, dressed in a classic dark suit, Booker Noe himself smiles when he sees the rack houses, the hot Kentucky sun bouncing rays off his bald head. On the classic Beam White Label bottle, Booker’s name is listed at the bottom as master distiller, under his grandfather’s name. He’s been making whiskey for fifty years, truly (and pardon the cliché) a legend in his own time.

“The last time I went to Wild Turkey ten years ago,” Booker says, “I was with Jimmy Russell [Turkey’s master distiller]. He says I got drunk. I say he got drunk. Goddamn! We all got drunk!”

At the wheel, Jim checks his watch and squirms nervously as we merge onto the Bluegrass Highway, in the heart of what is fondly called “the Bourbon Trail.” Looks like we’re running late. Booker appears nervous, as if the revelers might suck the entire Wild Turkey distillery dry before we get there.

“Now where was I?” he asks. He was telling a story about Jim Beam, his grandfather, and the last time he saw him alive. As the story goes, Booker says, he believes he might have killed his grandfather. That’s right: killed him.

“This is the God’s truth. Every word. Hell, I remember it like it was yesterday. It was December 25, 1947. I’d shot some birds, and I took these quail over to give my grandfather for Christmas. He was in bed, sick. I gave him the birds. My grandmother, his wife, asked him if it would be okay if she gave me his shotgun. He said yes, so she went and got this old gun, a Model 12 Winchester pump shotgun. It rolled seven shot, but you could only put three in there by law. During Prohibition, my grandfather was, among other things, a coal miner, and he used the gun to guard the mines. Anyway, I gave him the birds and he gave me the shotgun. That was Christmas Day.

“On the twenty-seventh, he was dead in bed,” Booker continues, “just like he was sleeping. Now I don’t know for sure, but I think he ate those birds. . . .”

Sounds like murder, right? More like manslaughter.

For the rest of the drive to Lawrenceburg for Jim Beam’s induction into the Bourbon Hall of Fame (a drive that took a little longer than expected because of a few wrong turns), Booker Noe continued telling stories that, collectively, piece together the life of his grandfather—stories about making Jim Beam whiskey, about Prohibition and Kentucky moonshiners, about the growth of the largest bourbon distillery in the world and more. With a whole bunch of gaps filled in (Booker’s memory gets foggy here and there), the following is a brief life of one of the greatest whiskey men in history, and the strange world of American distillers he was born into.

By the time the original Jim Beam kicked off his distilling career, whiskey was already a staple “resource” in Kentucky. When the first settlers came to the New World, they brought with them a distaste for “strong water.” (They were Puritans.) The original colonies in Massachusetts and New York were dry. But the Irish and Scottish settlers who came at the beginning of the eighteenth century had a taste for grain spirit, and they knew very well how to make it. They settled in what is now Maryland, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Virginia—states with fertile soil where rye grew plentifully.

All the ingredients necessary to make good whiskey were on hand: grain, pure water, forests to provide wood for lighting a fire under the still. By 1776, when the United States was born, smoke columns were rising off stills throughout the western part of the country.

The first Homestead Act offered free land grants to anyone with the guts to head west and settle in the wilderness. Among other places, thousands of pioneers of Scotch-Irish descent from Pennsylvania settled in Kentucky County, Virginia, where corn grew. Naturally, the settlers started making whiskey out of the grain, and they soon figured out that corn whiskey was much sweeter and arguably more full-flavored than rye. Have yourself a taste test of Jim Beam bourbon (bourbon must be at least 51 percent corn whiskey by law) and Jim Beam rye (with the yellow label) and you’ll be able to tell for yourself.

As Bill Samuels Jr., president of Maker’s Mark Distillery in Loretto, Kentucky, put it: “The fact that the native grain of Kentucky was Indian maize changed one of the key distinguishing elements between bourbon whiskey as we know it and other whiskeys.”

Eventually, distilleries sprang up around a particular section of what is now Kentucky where a thin layer of soil covered a huge limestone shelf. The limestone gave the water a particularly fresh flavor—great for making whiskey. (This same limestone is responsible for the state’s famous blue grass, which is rich in calcium and said to have given rise to the premium breed of Thoroughbred horses raised on it. It’s no coincidence that the greatest horse race in the nation is run in Kentucky.)

By the end of the eighteenth century, some two thousand small distilleries were operating in Kentucky. Among the early distillers, some have bourbons named after them that you can buy in stores today: Elijah Craig, a Baptist minister, the first to notice the fine flavor and caramel color whiskey gained when aged in charred oak barrels (according to legend, Craig used herring barrels, and the charring removed the fish odor); Evan Williams, a Welshman who established Kentucky’s first commercial distillery on Main Street in Louisville in 1783; Scot James Crow of Old Crow fame; and Jacob Beam, Jim’s great-grandfather, a distiller of German descent who sold his first barrel of whiskey in 1795.

Kentucky became the fifteenth state in 1792, and its fledgling government named one county after the French royal family—the Bourbons—in recognition of the support they gave to the Americans during the war against England. (There’s also a Louisville and a Versailles in Kentucky.) The whiskey made in Bourbon County had a strong reputation, and drinkers began to ask for it by name. Bourbon. Ironically, the county is dry today, just like Moore County in Tennessee, where Jack Daniel’s is made. The finest whiskey comes out of the counties just to the west, around Lawrenceburg and in particular Bardstown, a quaint hamlet not far from the Mason-Dixon Line.

If you stroll through Bardstown today, you can just barely smell the stink of grain fermenting as you pass by Toddy’s liquor shop, which has one of the finest collections of bourbons in the world, and a host of stores selling all manner of worthless souvenirs to tourists. As you near the end of town, there’s a large stately brick house right on Third Street, where one Jim Beam lived, and where Beam’s grandson Booker Noe lives today.

“He wasn’t any old blowhard like me,” says Booker about his grandfather, as we roll down the Bluegrass Highway toward Wild Turkey. “He was a quiet type of guy, debonair. He always wore a suit and tie, even when he went fishing.”

James “Jim” Beauregard Beam was sixteen when he first started making whiskey, under the tutelage of his father, David. The business was called the Clear Springs Distillery Company, and it was located down the road from where the main Jim Beam distillery is today. After fourteen years of training on the job, Jim took over in 1894—the fourth generation of Beams to run a still. The bottle of Beam White Label today says, SAME RECIPE SINCE 1795, in reference to a recipe devised by Jacob, Jim’s granddad, the first Beam to make whiskey in Kentucky.

Before Prohibition, the family distilled two brands of bourbon: Old Tub and Double Ford. The bottles were round and had no labels. Back in the horse-and-buggy days, Beam sold the whiskey to saloons, where drunks and businessmen alike drank it, sometimes before killing each other. Beam had a partner up in Chicago, and a brother, Tom Beam, in the saloon business in Kentucky. The word on Old Tub and Double Ford spread.

“He was not a chemist, see, but he knew about culturing yeast,” says Booker about his granddad. “He made the strain of yeast we use today. He didn’t have a microscope. Nowadays they use test tubes and microscopes. And he didn’t have a fridge either, so in the old days he kept the yeast in a well, ya see. Groundwater is about 56 degrees

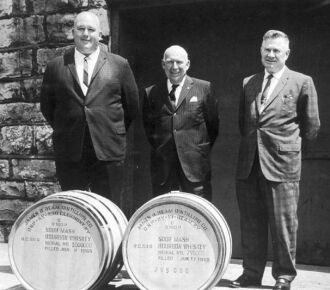

Booker Noe, T. Jeremiah Beam, Carl Beam, in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Jim Beam Brands Co.)

Fahrenheit all year round. So he hung it down there on a rope.” Apparently, Beam held his yeast in such esteem he kept some of it in his house just in case something happened to his other stashes. Visitors noticed the unique odor of the stuff when they walked through the door.

Beam also kept ledgers recording sales, which show that business was pretty good in those days. The burgeoning steamship and railroad industries made commerce easier, so the whiskey started showing up in saloons farther and farther west. You’ll notice that, in all the classic Western films, cowboys are drinking a brown liquid. Bourbon was the choice—and sometimes only—liquor available in the Wild West (unless you were tough, and perhaps dumb enough to land way down in tequila country). A lot of it was Beam’s bourbon.

There were some fifty other working distilleries in Kentucky before Prohibition—all of them booming, clouds of dark coal smoke from the stills billowing into the sky. Then, on October 28, 1919, the United States government put out the fire. The days of moonshiners, smugglers, and Al Capone had arrived.

By the time the government passed the Volstead Act, otherwise known as the National Prohibition Act, Jim Beam was fifty-six years old. He’d done little outside of the liquor business his entire life. But government agents were starting to comb the Kentucky countryside, carrying guns and wearing their game faces. A very few distilleries were allowed to continue operation to make “medicinal whiskey,” but Beam’s wasn’t one of them.

“I don’t want to end up in that penitentiary,” he told his family.

As grandson Booker points out, “Goddamn it! Outlawing alcohol was the dumbest thing the government ever did. People aren’t gonna do without their toddies! Their pick-me-ups! Hell.” Of that, there was no doubt. Jim Beam was able to sell his distillery pretty quickly to some “people who didn’t mind getting their hands dirty and doing it illicitly,” according to Booker. “A lot of them ended up in prison.”

During Prohibition, an underground liquor industry thrived in Kentucky. Because the stills shot columns of telltale smoke up in the air, the guys running them had to operate at night (thus the term “moonshiner”). The hooch had to go straight from the still to the middle man. It couldn’t be aged and darkened in charred oak barrels, where the cops would find it. So it was drunk clear and raw. It was called “white lightning” or “white dog” (because it had a nasty bite) or, as one witty writer recently joked, “Kentucky sushi.”

A lot of the liquor went up north to Chicago, where one Al Capone was making more than $60,000 a year selling the stuff, quite a bit of money at the time. Gang warfare escalated over liquor turf, culminating in the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago in 1929, when Capone’s thugs shot seven of rival gang leader “Bugs” Moran’s men dead.

“In its practical effects,” says Andrew Sinclair in his book Prohibition: The Era of Excess, “national prohibition transferred $2 billion a year from the hands of brewers, distillers, and shareholders to the hands of murderers, crooks, and illiterates.”

Meanwhile, Jim Beam was making a successful living. He invested in a coal mine in the mountains of western Kentucky, a rock quarry around the corner from the old Beam distillery, and some citrus groves in Florida. Wearing his trademark black three-piece suit and tie, white shirt, round spectacles, and pocket watch, he guarded his mines with the shotgun he’d eventually pass on to his grandson. He went on frequent fishing trips in Canada. He worked on his house, a redbrick building on the edge of Bardstown, which he purchased from the Bardstown Girls’ Academy. All was well, but the taste for making whiskey never left him.

In the 1932 presidential election, the Democrats ran on a platform aiming to abolish the Prohibition Act, with a candidate who would go on to serve four terms—Franklin Delano Roosevelt (who preferred a Dirty Martini by the way). FDR was no fool. Naturally, he won, and on December 5, 1933, the federal government repealed the Eighteenth Amendment.

On December 7, just two days later, Jim Beam—now seventy years old—applied for a new distilling license and was assigned DSP License Number 230, the same one he’d had before Prohibition. With the help of his son Jeremiah, fresh out of the University of Kentucky, Beam rebuilt the distillery in one hundred twenty days in Clermont, where the company’s main facility is today. Rather than Old Tub or Double Ford, as the Beam whiskey was called before, he decided to name the new liquor Jim Beam Kentucky Straight Bourbon.

If there was any good news for the whiskey business to come out of Prohibition, it was the fact that drinking on the sly made it impossible to get off on beer and wine. You had to go for the greater bang per ounce so you could get drunk on whatever could fit in a flask concealed in your pocket. Whiskey and gin emerged as the drinks of choice when Prohibition was repealed.

The name aside, Jim Beam’s new whiskey wasn’t any different from the old stuff: a liquor made from very specific amounts of corn, barley, and rye, aged four years in new charred oak barrels. Beam created a fresh white label with his name on it. Competition was tough; the flood of Canadian whiskey over the border during and after Prohibition made things hard on American distillers at first. Whiskey had to be aged before it could hit the market, but in Canada reserves were ready to go. (See Seagram’s: A Dynasty Founded on Rumrunning later in the book.) Still, Beam’s booze was a hit in no time, and it was quickly on its way to becoming the bestselling bourbon in the world.

“He worked all the time,” remembers Booker. “Whiskey was what he knew. He made good whiskey and people loved it.” Just a teenager back then, Booker began spending more time with his grandfather—going fishing, strolling around the distillery, cruising in the old man’s 1939 Cadillac Coupe. “He was known to have a highball sometimes,” Booker says, “but honest to God, I never once saw him take a drink. He didn’t set around like me and drink. I drink at the drop of a hat. Hey, you’re not going to print that are ya? Aw, shit. I don’t give a damn what ya write. Hell.”

Jim Beam died in December 1947, at his home in Bardstown, quite possibly at the hands of his grandson, Booker, who’d delivered him some birds to eat two days earlier on Christmas Day. “He made it to eighty-three, which is pretty good, especially in those days,” Booker notes. “He got baptized three months before, so if he’d done any sinning in his life, it all disappeared before he died.” Four years later, in August 1951, Booker, then twenty-one years old, joined the company.

By that time, Jim Beam’s son, Jeremiah, was running the show. The whiskey was all handmade, “stirred with a stick.” A decade later, Booker became master distiller. Over the next forty years, a Rube Goldberg–style assembly line would take the place of the factory’s old-fashioned innards, and production would increase by twelve times. “When I started we made forty thousand gallons a week,” says Booker. “Now we make eighty thousand gallons a day. We use the same grain, the same yeast, the same everything. But it’s all automated.”

Today, Booker’s son, Freddy, is running the business side, while one Jerry Dalton has become the master distiller, the first non-Beam to hold the title. Under their command, the company filled its nine millionth barrel of whiskey in July 2002, the tally counting only liquor made since Jim Beam incorporated after Prohibition. That comes out to be, oh, 280 million cases of bourbon, or 115 billion drinks.

As we are driving home from the Wild Turkey distillery after the Bourbon Hall of Fame party, one of those nasty Kentucky rainstorms sweeps over the highway. In the passenger’s-side front seat, Booker rolls his eyes and stares out the windshield, which looks like it’s been coated with Vaseline. In the backseat, a trophy copper still with a black plaque honoring Jim Beam’s induction to the Hall of Fame sits next to Booker’s gray fedora.

“Whoa!” Booker yells, the rain blinding us. “You watch that road, Jim! You put on your brakes on that goddamn slick highway . . . oh, hell. Damn!”

“I got it,” says Jim, white knuckling the wheel, his eyes straining to catch a glimpse of the double yellow line.

“Goddamn!” Booker says again. “Now where was I?” He was talking about how much he likes drinking his own brand of bourbon—Booker’s—and about his diabetes. Aren’t people who have blood sugar problems like diabetes supposed to lay off the booze? “Hell no!” he says. “If I stayed plastered all the time, I’d be fine. But the liver can’t handle it. Are you quoting me? Aw, hell, I don’t give a shit. I have a toddy every day. Several! It levels off the sugar in your blood. Ask any doctor.” By the way, he’s dead wrong.

JIM BEAM’S SMALL BATCH BOURBONS

School days were all about drinking White Label shots with beer chasers. And for folks who manage to graduate . . .

BAKER’S: A deep amber whiskey with hints of fruit, caramel, and nut, this bourbon is generally a hit among folks who like cognac. (Baker’s happens to be my favorite bourbon in the world, if that counts for anything.) It’s made from an old family recipe preferred by Jim Beam’s grandnephew, Baker Beam, using an old strain of jug yeast that’s been in the family for decades. The whiskey is aged seven years and comes dressed up in a slope-shoulder wine bottle.

BASIL HAYDEN: This delicious whiskey’s named after an eighteenth-century master distiller. Basil Hayden grew up in Maryland, where he learned to make rye. When he moved to Kentucky in 1796, Hayden added corn to the recipe, the same recipe the Jim Beam distillery uses to produce the bottle that now bears his name. The mash contains twice as much rye as most other bourbons, and you can taste it. Aged eight years and bottled at 80 proof, Basil Hayden is light and mellow on the tongue—great for breakfast or first-time drinkers.

KNOB CREEK: This drink’s named after Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home in Kentucky. The best known of all small batch bourbons these days, Knob Creek spends nine years “getting to know the inside of a new charred American white oak barrel,” as the Beam folks like to put it. The barrels are charred up to “level four,” meaning they’re burned pretty good. The dark caramelized wood gives the whiskey its signature earthy aroma, delicate sweetness, and dark amber color. It’s bottled at 100 proof, like most good bourbons were way back when.

BOOKER’S: For years, Beam master distiller emeritus Booker Noe used to bottle a bourbon straight from the barrel at Christmastime for his friends—uncut, unfiltered, untouched. The stuff became a hit among in-the-know locals. So in 1988, he decided to brand and market it (Booker’s True Barrel Bourbon). This liquor goes down like a hot mystery novel—hints and clues of flavors (oak, tobacco, vanilla), legs that coat a glass like fishnet, and a long, hot finish. At proofs that vary from barrel to barrel (121–127 proof), Booker’s comes with a Joe Frazier–style right hook packed inside each bottle.

So when Booker pours a tall one, does he like to drink, say, Wild Turkey? Maker’s Mark?

“Don’t ask me no dumb-ass questions. I drink Booker’s bourbon, with water. Booker’s has the most body. It has the most flavor.”

Back in 1987, the old man launched his own “small batch” bourbon, bottled under his own name. To produce the stuff, he personally samples barrels of the finest whiskey from what he calls the “center cut” of the rack house, bourbon aged six to eight years. Booker’s is sold in a wine bottle, available in varying strengths depending on the batch, from 121 to 127 proof. In other words, it mixes well with a dash of water. Booker himself is a walking advertisement.

“As far as I know, it’s the only uncut, unfiltered, unadulterated bourbon in the world—straight from the barrel. Goddamn right! That’s the way it was one hundred fifty years ago, and that’s the way I like it.”

As we pull up into Bardstown, the rain stops and the sun cuts through the clouds. Jim pulls around a corner and into the driveway of a redbrick house with a large front lawn and a circular blossoming flower bed. Welcome to the original Jim Beam’s house, at one time the Bardstown Girls’ Academy, now the home of Jim Beam Brands master distiller emeritus Booker Noe. The home is a big but modest place, a classic old suburban beauty with a couple added touches out back—a smokehouse for ham and a makeshift pond where Booker keeps bluegill for eating. (The pond looks like a giant hot tub that hasn’t been cleaned in, well, ever.) His son, Freddy, lives right next door.

Booker climbs out of the minivan and slams the door shut behind him. Without looking back, he waves his hand in the air and says with a deep Southern drawl, “Allll right.” Then he opens the door to his house and disappears inside, where his Jack Russell terrier, Spot, is waiting, and no doubt a toddy of Booker’s bourbon as well.

THE MINT JULEP

The julep is probably as old as alcohol itself, perhaps even older. The Arabs called it julab. The Persians called it gulab. Technically, it means rose water, and it came to denote any liquid infused with the essence of something else. Here in the States, julep generally means bourbon flavored with sugar and mint. And make sure you get the mixology right, lest you wind up on the business end of a double barrel.

As the prevailing legend has it, the origin of the Mint Julep goes something like this: One day, a transient on the Mississippi came ashore hunting for some springwater to dilute a stiff batch of whiskey. Finding some wild mint growing on the riverbank, he tossed a bunch in. That’s pretty much the story, with the noted exception of a dash of sugar, which was added later. Way back in 1820, the Old American Encyclopedia described drinking in the South: “A fashion at the South was to take a glass of whiskey, flavored with mint, soon after waking; and so conducive to health was this nostrum esteemed that no sex, and scarcely any age, were deemed exempt from its application.”

Today, the Mint Julep is a staple drink all over the South. It’s also the official drink of the Kentucky Derby. The following recipe is my favorite, culled from a variety of sources in Bardstown and Louisville, Kentucky. It’ll take twenty-four hours, so plan accordingly.

Make a batch of simple syrup. Throw a cup of plain granulated white sugar and a cup of freshwater (springwater if possible) into a pot. Heat it until the sugar melts into the water, stirring occasionally. Then let it cool.

Make a batch of simple syrup. Throw a cup of plain granulated white sugar and a cup of freshwater (springwater if possible) into a pot. Heat it until the sugar melts into the water, stirring occasionally. Then let it cool.

Take a pile of fresh mint leaves without stems, about enough to make a loose ball the size of a large fist. Throw that in a big bowl with a cup of bourbon. Then muddle it up using any instrument you’ve got.

Take a pile of fresh mint leaves without stems, about enough to make a loose ball the size of a large fist. Throw that in a big bowl with a cup of bourbon. Then muddle it up using any instrument you’ve got.

Take a break for a couple hours. Ask yourself, what is life? Is there a God? Should socks always have to match, or is it okay to wear a blue one and a black one if you’re sure that no one will notice?

Take a break for a couple hours. Ask yourself, what is life? Is there a God? Should socks always have to match, or is it okay to wear a blue one and a black one if you’re sure that no one will notice?

Take the rest of the bottle of bourbon and dump it in the bowl, along with about a cup to a cup and a half of your cooled syrup. (However you like—taste it as you go.) Stir the concoction; then put it in the refrigerator overnight.

Take the rest of the bottle of bourbon and dump it in the bowl, along with about a cup to a cup and a half of your cooled syrup. (However you like—taste it as you go.) Stir the concoction; then put it in the refrigerator overnight.

Wake up the next day. Put tall cocktail glasses in the freezer to chill. Then invite some friends over.

Wake up the next day. Put tall cocktail glasses in the freezer to chill. Then invite some friends over.

When ready, fill your chilled cocktail glasses with crushed ice (snobby Southern folk will require silver cups). Stir up your Mint Julep, and start pouring. Garnish with a mint sprig, and raise a toast.

When ready, fill your chilled cocktail glasses with crushed ice (snobby Southern folk will require silver cups). Stir up your Mint Julep, and start pouring. Garnish with a mint sprig, and raise a toast.