WHAT TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY IS FOR

Placing the Doctrine of the Trinity in Christian Theology and Life

FRED SANDERS

THE CHURCH OF ST. SERVATIUS in Siegburg, Germany, has a treasure room full of medieval art and relics. Among the artifacts is a portable altar crafted around the year 1160 by the workshop of Eilbertus of Cologne (see next page).1 Eilbertus was a master craftsman of Romanesque metalwork and enamel decoration, a sturdy artistic medium that withstands the centuries with minimal fading or decay. The colors remain brilliant after nearly a millennium. But Eilbertus was also a skillful iconographer, whose fluency with the symbolism of Christian art equipped him to construct dense and elaborate visual arguments. Consider the top of the altar box. Ranged in bands along the top and bottom of it are the twelve “apostles of the Lord,” labeled apostoli domini. Running down the right border are three ways of depicting Christ’s victory over death: at the bottom is the post-resurrection appearance to Mary Magdalene in the garden, at the center is the “empty tomb” (sepulchru domini) with sleeping soldiers and the three women seeking the Lord among the dead, where he is not to be found, and at the top is the “ascension of Christ” (ascensio Christi). The event of the resurrection itself is not directly portrayed, of course, but Eilbertus juxtaposes three images of the resurrection’s consequences: the presence of the Lord to his people, the absence of the Lord from the tomb, and the ascension of the Lord by which he is now both present to us (spiritually) and absent from us (bodily) until his return. If a picture is worth a thousand words, three pictures placed together in significant visual proximity are not increased simply by addition of ideas, but rather by a remarkable multiplication of meaning.

But it is the left border that showcases Eilbertus as the iconographic and doctrinal master that he is. In the middle is the crucifixion of Jesus, where the Son of God is flanked by his mother Mary and John the evangelist, as well as by the moon weeping and the sun hiding his face. At the foot of the cross, from the feet of the Savior runs the blood of the crucified, and as it runs down the hill of the Skull, it crosses a rectilinear panel border in which is inscribed passio Christi (“the passion of Christ”). The blood runs out of its own frame and into an adjoining visual space, a space in which Adam (clearly labeled Adam, which is Latin for . . . “Adam”) is rising from a sepulcher. Adam’s arms are outstretched in a gesture of reception, but they also set up a powerful visual echo of the outstretched arms of Jesus. Adam’s tomb and its lid are arranged perpendicular to each other, so that Adam’s body is framed by an understated cruciform shape of the same blue and green colored rectangles as Christ’s.

Eilbertus is making another visual argument here: where the two crosses cross, salvation takes place. Because the second Adam bends his head and looks down from his death, the first Adam raises his head and looks up from his. Eilbertus is offering an invitation here: above are the everlasting arms, outstretched but unbent, as linear and straight as panel borders or the beams of the cross, while below the salvation is received with appropriate passivity into the bent arms of the father of the race of humanity. Redemption is accomplished and applied, and at long last an answer is given to God’s first interrogative: “Adam, where are you?”

But even this is not the peak or extent of Eilbertus’ iconographic teaching. For that master stroke we have to look not below the cross but above it. In another pictorial space, framed by both a square and a circle, is God the Father flanked by angels. It doesn’t look much like God the Father. It looks instead exactly like Jesus, right down to the cross inscribed in the halo. Pity the iconographer who has to represent the first person of the Trinity visually. As a general rule, the Father should not be portrayed: even in the churches that use icons in worship, stand-alone images of the Father are marginal, aberrant, noncanonical. Do you portray him as an elderly man with a flowing white beard, as if he were modeled on Moses or even perhaps Zeus? Eilbertus has taken the imperfect but safe route and depicted the Father christomorphically. Since Christ told his disciples “Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9), it stands to reason that if an artist decides to show the Father, he should show him looking like what we have seen in the face of Jesus.

Representing God the Father visually is a problem not even Eilbertus can solve, and even though other options might be worse, this christomorphic Father is nevertheless a rather regrettable solution. But if you avert your eyes from that difficult figure, you will notice the dove of the Holy Spirit ascending from Christ on the cross. The dove imagery is, of course, not found at the end of the Gospels ascending from Golgotha, but rather at the beginning of the Gospels, descending at the Jordan, onto the scene of the baptism of Christ. Eilbertus has moved the symbol here to provide a visual cue for something like Heb 9:14, where we are told that “Christ . . . through the eternal Spirit offered himself unblemished to God.” Just as the blood broke the bottom border, the dove breaks this upper border, crossing over from the Son to the Father. The dove also breaks the crucial word, the label that makes sense of it all: trinitas (“Trinity”).

It’s a little word, but it changes everything. Simply by juxtaposing the death of Christ with a visual evocation of God in heaven, Eilbertus indicates that what happened once upon a time in Jerusalem, a thousand years before Romanesque enamels and two thousand years before the internet, is not simply an occurrence in world history but an event that breaks in from above, or behind, or beyond it — an event in which God has made himself known and taken decisive divine action. But by adding the word trinitas, the artist has turned scribe and has proclaimed that what we see at the cross is in some manner a revelation of who God is. Here God did not just cause salvation from afar, but caused himself to be known as the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Here we cannot press Eilbertus any further, because the diction of enamel and the grammar of metalwork are not precise enough to say what we must go on to say. Eilbertus has reminded us of the essential movement that we must make, has set us on the path that faith seeking understanding must follow: from the history of salvation to the eternal life and unchanging character of God. But it is high time to come to terms with the precise meaning of that movement, and for that task we need not images depicting the truth, but words: first the form of sound doctrine given in the teaching of the apostles, then the interpretive assistance of classical doctrines, and finally the conceptual redescription that characterizes constructive systematic theology in the present. The craft and wisdom of Eilbertus frame the discussion, but we need to have the discussion.

In this chapter I want to characterize not the doctrine of the Trinity itself, but how it functions within systematic theology. The adjective in the phrase “trinitarian theology” is grammatically ambiguous, since it could indicate either a theology that is about the Trinity, or an overall theological system that is shaped and conditioned by the doctrine of the Trinity. The latter sense is what I intend to describe by exploring what the doctrine of the Trinity is for; what follows is an account of the dogmatic function of the doctrine of the Trinity in the overall structure of Christian theology and life. Under the guiding image of Eilbertus, we have already begun the task of considering the events of salvation history against the background of the eternal being of God; the doctrine of the Trinity poses “the question of how salvation history is to be correlated with the divine being in itself,” or “to describe the connection between God and the economy of salvation.”2 As it does this, this doctrine provides five services that promote the health and balance of Christian theology as a whole. First, trinitarian theology summarizes the biblical story. Second, it articulates the content of divine self-revelation by specifying what has been revealed. Third, it orders doctrinal discourse. Fourth, it identifies God by the gospel. And fifth, it informs and norms soteriology.

1. SUMMARIZING THE BIBLICAL STORY

The easiest angle of approach to the Trinity begins with a straightforward reading of the Gospels as rather obviously the story of three special characters: Jesus Christ; the Father, who sent him and who is constantly present in his conversation and actions; and then, rather less clearly, the Holy Spirit, who seems simultaneously to precede Christ, accompany Christ, and follow Christ. There are many other characters in the story, but these three stand out as the central agents on whom everything turns. The actions of these three are concerted, coordinated, and sometimes conjoined so that sometimes they can scarcely be distinguished; at other times they stand in a kind of opposition to each other. As for the salvation they bring, it is not three salvations but one complex event happening in three ways, or (as it sometimes seems) one project undertaken by three agents. The New Testament epistles, each in their own way, all look back on and explain this threefold story, adding more layers of analysis and insight but not altering the fundamental shape of what happened in the life of Jesus.

We could summarize this threefold shape of the New Testament story in the formula, “The Father sends the Son and the Holy Spirit.” And though we can’t take the time to develop it here, we would then have to extend the analysis to include the entire canon, to demonstrate that what happens in the New Testament is a continuation and fulfillment of what happened in the Old. To trace the story line of Scripture, and especially of the Old Testament, as the God of Israel promising to be with his people in a Son of David who is the Son of God, and to pour out his Holy Spirit on all flesh in a surprising fulfillment of the promise to Abraham, is a task for a comprehensive biblical theology, but it can be undertaken while remaining in the mode of mere description, rather than moving to the more contentious field of systematic construction. In that case, giving a particular kind of interpretive priority to the New Testament because of its position at the end of a process of progressive revelation, the sentence “The Father sends the Son and the Holy Spirit” would be a summary of the entire Bible.

This particular threefold formula is not the only possible summary of the story line of the Bible. Other themes in salvation history could be highlighted. Even other threefold patterns could be discerned: exodus, exile, and resurrection suggests itself. The themes of kingdom or covenant could be pushed to the foreground, or even substituted for the Father, Son, Holy Spirit schema. Much can be gained from investigations that give prominence to these other themes, but what I am describing here is how to read the salvation history witnessed in Scripture in such a way as to reach the doctrine of the Trinity. The reason we would want to do that as Christians is that only the trinitarian reading is actually attempting to read salvation history as the revelation of God’s identity in a way that transcends salvation history; such a reading shows not only what God does but who God is. The stories of kingdom or covenant, of exodus, exile, and resurrection, could remain personally undisclosed except insofar as his faithfulness to stand reliably behind his actions suggests something about him. The trinitarian reading of salvation history goes further: it construes the divine oikonomia (God’s wise ordering of salvation history) to be simultaneously an oikonomia of rescue, redemption, and revelation — indeed self-revelation. Salvation history on the trinitarian reading is the locus in which God makes himself known, the theater not only of divine action but also of divine self-communication. A faithful God may stand behind other construals of salvation history, but on the trinitarian reading, God stands not behind but also in his actions, at least in the actions of sending the Son and the Holy Spirit.

There are numerous advantages to beginning in this way. In our age, many Bible-believing Christians have trouble seeing the doctrine of the Trinity in Scripture. They see a verse here and a verse there that help prove the different parts of the doctrine (the deity of Christ, the unity of God, etc.), but they struggle to see the whole package put together in any one place. Granting that the doctrine is not compactly gathered into any one verse (not even Matthew 28:19 or 2 Corinthians 13:13 (13:14 in NIV) are as complete or as detailed as could be wished), it is beneficial to approach the doctrine in a bigger-than-one-verse way.

Follow the whole argument of Galatians 4, for example (in the fullness of time, God sent his Son, and has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying “Abba, Father”), or 1 Corinthians 2 (in apostolic foolishness we have the mind of Christ and we have the Spirit, who searches the deep things of God), or of Ephesians 1 (we are blessed with every spiritual blessing by the Father, who chose us before the foundation of the world, gave redemption in the blood of the beloved Son, and sealed us with the Spirit of promise), or of the Gospel of John (the Word became flesh, talked endlessly about the Father who sent him, and then gave the Spirit), and the trinitarian profile of God’s self-revelation emerges clearly. We have to train our minds to think in bigger sections of Scripture than just a verse here and a verse there — the bigger the better.

To arrive at the biblical doctrine of the Trinity requires three large mental steps. The first step is simply to read the whole Bible, to achieve some initial mastery of the long, main lines of the one story that is the Christian Bible. An interpreter needs to be able to think back and forth along the canon of Scripture, with figures like Abraham and Moses and David and Cyrus standing in their proper places, and with categories like temple and sonship and holiness lighting up the various books as appropriate. This familiarity and fluency with all the constituent parts are prerequisite for further steps.

The second step, though, advances beyond canonical mastery by understanding not just the shape of the biblical text but of God’s economy. What is required here is to comprehend the entire Bible as the official, inspired report of the one central thing that God is doing for the world. God has ordered all of these words and events that are recorded in Scripture toward one end. Simply knowing the content of the entire Bible is inadequate, if that content is misinterpreted as a haphazard assemblage of divine stops and starts. These are not disparate Bible stories, but the written witness of the one grand movement in which God disposes all his works and words toward making himself known and present.

The third step is to recognize the economy as a revelation of who God is. This is the largest step of all. Once interpreters have mastered the contents of the Bible and then understood that it presents to us God’s well-ordered economy, they still need to come to see that God is making himself known to us in that economy. After all, it is theoretically possible for God to do great things in world history without really giving away his character or disclosing his identity in doing so. This final step on the way to the doctrine of the Trinity is to recognize that God behaved as Father, Son, and Spirit in the economy because he was revealing to us who he eternally is, in himself. The joint sending of the Son and the Holy Spirit was not merely another event in a series of divine actions. It was rather the revelation of God’s own identity: the doctrine of the Trinity commits us to affirming that God put himself into the gospel.

This is, I claim, the right way to interpret the Bible, and it is also a rough summary of the traditional way the Bible has been interpreted classically, recognized by the church fathers and the Reformers. We could call it the Christian way. It yields the doctrine of the Trinity, not in scattered verses here and there that tell us a weird doctrine at the margins of the faith, but as the main point.

The New Testament obviously features these three characters: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Classically, Christian theology has traced these persons back to an eternal Trinity of God in se. Since this threefoldness belongs to what God actually is rather than only being something he freely does, it has been called the ontological Trinity, the essential Trinity, or the Trinity of being. Theologians have also called it the immanent Trinity, because “immanent” means “internal to” itself.

In summary, the most crucial conceptual step that must be taken is the move from the events of the economy of salvation to the eternal life of God. This is the crucial step, and it is a step taken with the fewest explicit and concise expressions: verses. Because of the uniquely integral character of the doctrine of the Trinity, it resists being formulated bit by bit from fragmentary elements of evidence. The atomistic approach can never accomplish or ground the necessary transposition of the biblical evidence from the salvation-history level to the transcendent level of the immanent Trinity. Such a transposition requires first the ability to perceive all of the economic evidence at once, including the intricately structured relations among the three persons. As a coherent body of evidence, then, that economic information can be rightly interpreted as a revelation of God’s own life. To make the jump from economy to Trinity, the interpreter must perceive the meaningful form of a threefold divine life circulating around the work of Christ. What psychologists of perception call a gestalt, a recognizably unified coherent form, is what the trinitarian interpreter must identify in the economy. This triune form, once recognized, can then be understood as enacting, among us, the contours of God’s own triune life. He is among us what he is in himself: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

2. ARTICULATING THE CONTENT OF DIVINE SELF-REVELATION

Summarizing the biblical story requires an ascent of thought from the economy to the divine being; this is the distinctive movement of thought that makes possible the doctrine of the Trinity. For the sake of clarity, the question that needs to be posed more explicitly is the question of how much the economic Trinity reveals about God’s eternal and essential being. As nineteenth-century Congregationalist theologian R. W. Dale said, the most important question in trinitarian theology is “whether in the Incarnation of our Lord and in the ‘coming’ of the Spirit and His permanent activity in the Church and in the world there is a revelation of the inner and eternal life of God.”3 In other words, “have we the right to assume that the historic manifestation of God to our race discloses anything of God’s own eternal being?”4 Dale answers yes, as all trinitarians, by definition, do. But trinitarian theologians have developed different opinions about what precisely is revealed. The decisions we make here are the master decisions, affecting everything we say about trinitarian theology’s other tasks, namely, to express the material content of the whole doctrine. If we say the right things about divine self-revelation in salvation history, the other tasks will fall more easily into place: doctrinal discourse will be better ordered, God will be identified by the gospel, and our soteriology will be properly informed and normed thereby.

So much good work is to be done at the level of describing salvation history holistically that we might reasonably ask whether it is really necessary to transcend the economy and make claims about the God behind it. Even without angling for a trinitarian conclusion, the answer is yes. If Christian salvation is a real relationship with the true God, some such step is necessary. This is a point that Thomas Torrance made with great force and consistency throughout his work:

the historical manifestations of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have evangelical and theological significance only as they have a transhistorical and transfinite reference beyond to an ultimate ground in God himself. They cannot be Gospel if their reference breaks off at the finite boundaries of this world of space and time, for as such they would be empty of divine validity and saving significance — they would leave us trapped in some kind of historical positivism. The historical manifestations of the Trinity are Gospel, however, if they are grounded beyond history in the eternal personal distinctions between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit inherent in the Godhead, that is, if the Fatherhood of the Father, the Sonship of the Son, and the Communion of the Spirit belong to the inner life of God and constitute his very Being.5

The fact that God makes himself known to us as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit because he is in himself Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is the occasion for wonder and praise, especially since God did not make this revelation to satisfy our curiosity about the divine, but in order to reconcile and redeem us. God the Father did not tell us he had a Son and a Spirit, but he sent them to be among us. And the Son and Spirit did not come to us in order to transmit information, but to do the work of saving, with the information about their existence and their nature being a necessary accompaniment to their saving presence. Considered from this angle, the correspondence between who God is in himself and who he shows himself to be in the economy of salvation is something we receive with praise, raising our bent arms like Adam. Theology in this mode is doxology, the praise of God.

But considered as a reflective theological movement of thought from below to above, the relationship between the economy and the eternal life of God is an intellectual project whose closest analogues are observation, induction, and the formation of conceptual models. Here theology has to be rigorous, consistent, creative in articulating how the various elements of the biblical witness are to be integrated, and accountable to others. It is all well and good to assert, as Karl Barth does, that “to the involution and convolution of the three modes of being in the essence of God there corresponds exactly their involution and convolution in his work.”6 But the actual work begins when we describe how the particular involution and convolution seen in the economic relations among Jesus Christ, his Father, and their Spirit are to be construed as revealing the very life of God. Theology in this mode is not just doxology, but “the praise of God by crafting concepts to turn the mind to the divine splendor.”7

When we ask, “What does the economy signify about God’s eternal life?” we have first the challenge of how to draw such inferences, and second the range of options that emerge in answering the question. First, we will examine the rules and restrictions on the inferences.

Not everything that God does is to be taken as revelatory of what he is. Some of what happens in the economy stays in the economy. Some obvious examples would be aspects of the incarnation that have to do with the Son’s appropriating a human nature: If Jesus has brown eyes, should we say that the eternal Son before the foundation of the world had this feature? No. There are other, nonbiological aspects of salvation history that have more to do with the nature of the humanity being saved than the character of the person doing the saving. As we consider aspects of salvation history and what they reveal about the life of God in himself, we should bear in mind certain limitations.

A set of three limitations attaches to the notion of divine self-communication. First, divine self-revelation takes place under the form of some condescension from majesty, such that God in the incarnate Son and outpoured Spirit does not appear in his own proper glory but in a humbled form. As a result, second, it requires accommodation to human terms. As patristic discussion helped to clarify, even the term “sonship” is a term first learned from human relationships before God shows us that it applies analogically to a transcendent reality. The writings of Pseudo-Dionysius are a potent witness to the Christian theological tradition of understanding God’s self-revelation as being simultaneously an unveiling of the truth about God and a veiling of the divine being behind revealed concepts and images. Calvin likewise describes God’s speech as taking the form of divine “lisping,” by which God speaks the truth about himself, but in a manner that is adjusted to be appropriate to our understanding. Calvin is also an eloquent advocate of the third restriction, which is divine reserve: God knows that some truths about divinity would not be beneficial or edifying for us, and so he withholds them from revelation. Anything that God does show or tell us, then, is selected from a larger pool of divine truth, things that are not shown or told for reasons reserved to God’s inscrutable wisdom.

Another set of three limitations attach to the fact that the incarnation is the central point of God’s self-revelatory presence. First, incarnation means that God is present under conditions of createdness, since the eternal Son of God took to himself a true human nature, which, considered in itself, is creaturely. This means that in the incarnation God appears under the sign of his opposite, or at least by taking a stand on the other side of the creator-creature distinction. Entailed by createdness, second, is the fact that what God makes known here is made known under conditions of temporality and multiplicity, whereby the God who does one continuous eternal act of faithful love must act out that same act repeatedly, in a temporally extended way, to continually manifest who he is in the schema of successive moments. Third, the incarnational focus of divine self-revelation means that the Son of God undertakes his mission as a participation in our fallen human plight, not for his own sake but “for us and for our salvation,” as the Nicene Creeds says. This being the case, what we see in Christ is God being himself under conditions that are not his native sphere, so to speak.

Any particular observation we make about God’s presence in the Son and the Spirit runs the risk of bouncing off these barriers. These barriers to inference are formidable, but none of them is sufficient to block all real knowledge. In fact, the trinitarian schema is uniquely well suited to pierce these barriers and deliver personal knowledge of God. Consider, for example, the way trinitarianism accounts for how God becomes man: not by deity becoming humanity, nor by God showing up in his majesty and lordship to exert sovereignty in the flesh and demand the worship due him. Instead, on the trinitarian view, the Father sends the Son, and so the divine person of the Son can appear under the sign of his opposite (strength as weakness, lordship as obedience, etc.) while still making known the character of God. Austin Farrer puts it this way:

God cannot live an identically godlike life in eternity and in a human story. But the divine Son can make an identical response to his Father, whether in the love of the blessed Trinity or in the fulfilment of an earthly ministry. All the conditions of action are different on the two levels; the filial response is one. Above, the appropriate response is a cooperation in sovereignty and an interchange of eternal joys. Then the Son gives back to the Father all that the Father is. Below, in the incarnate life, the appropriate response is an obedience to inspiration, a waiting for direction, an acceptance of suffering, a rectitude of choice, a resistance to temptation, a willingness to die. For such things are the stuff of our existence; and it was in this very stuff that Christ worked out the theme of heavenly sonship, proving himself on earth the very thing he was in heaven; that is, a continuous perfect act of filial love.8

As Farrer says, it is impossible to imagine how God would act if God were a creature. To put the question that way is to force ourselves into an unresolved paradox: Would he act like the creator, or like a creature? What action could he take that would show him to be both? When the incarnate God walked on water, was he acting like the creator or the created? None of these questions are the kind of questions the New Testament puts before us. What the apostles want to show is that Jesus was the Son; he came, lived, taught, acted, died, and rose again like the Son of God.

It was the eternal Son, whose personal characteristic is to belong to the Father and receive his identity from the Father, who took on human nature and lived among us. His life as a human being was a new event in history, but he lived out in his human life the exact same sonship that makes him who he is from all eternity as the second person of the Trinity, God the Son. So when he said he was the Son of God, and when he behaved like the Son of God, he was being himself and explaining himself in the new situation of the human existence he had been sent into the world to take up. Notice that Jesus does not merely act out sonship, but also declares it and describes it. I do not want to give the impression that God’s self-revelation is a pantomime routine, in which our job is to guess the right words from divine actions in history. No; Jesus as the incarnate Son is eloquent; he tells us he is the Son, and then he behaves as such. God’s self-revelation is not charades, but show-and-tell. Our inference is always hermeneutics, always irreducibly textually mediated.

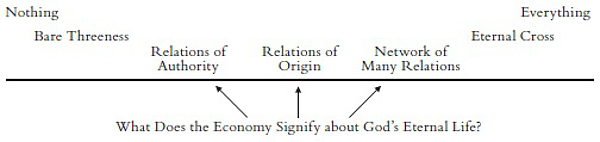

Once we pose the question openly: what do the sendings of the Son and the Holy Spirit signify about the eternal life of God? we need to consider the range of possible inferences from the economy of salvation. Consider the possible answers as ranged on a spectrum with the classic answer at the center: the sending of the Son signifies the eternal relation of generation from the Father, and the sending of the Spirit signifies the eternal relation of the breathing of the Spirit from the Father. Ranging to the left are more minimal positions, and to the right are more maximal positions.

To begin with a glance at the extreme minimalist side, we can see that it is possible to deny that the coming of the Son and Spirit reveal anything whatsoever about the being of God. God shows nothing in the economy; he does something, but shows nothing. The most illuminating light in which to consider unitarian theologies is as the entirely negative answer to the question of what the divine reveals about itself in the history of salvation. Heresies like monarchian modalism, in which the one unipersonal God behaves three ways in his actions toward us, are also best understood as minimalistic answers to our basic question.

But what about the maximalist answer? What if God reveals everything in the history of salvation? This equally radical view on the other end of the spectrum takes all divine action in history and eternalizes it. It is a hard view to maintain because it requires a total rethinking of metaphysics. So Hegel has been the leading spirit, and anglo-American process theology a distant second. The sendings of the Son and Spirit reveal God in this case, but so does everything God does, because the divine nature is actualized fully and only in the history of salvation. In fact, on this view, it is hard to explain why the sendings of the Son and the Spirit should be considered equally important as the comprehensive events of creation and consummation.

The extremes are full of instructive errors, but perhaps the most basic error they share is the assumption that the economy can be interpreted using a general principle of self-revelation. For our purposes, the extremes serve as a warning that our inference from the economy is not a general principle of God-world relatedness, but something we had to be told. Whatever riches of the knowledge of God are revealed in the history of salvation, to approach the history as if it were self-evidently God’s self-revelation would run perilously close to positing a general principle about the God-world relationship, a general principle that would itself be underdetermined by revelation. Divine revelation is inalienably linked to intention on the part of the revealer, and “unfolds through deeds and words bound together by an inner dynamism,” to use the words of Vatican II’s Dei Verbum. Notice also that the two extremes both give rise to modalism. The nothing option gives us monarchian modalism in which one God does three things, whereas the everything option gives us dynamic modalism, in which the one God becomes three persons by self-actualizing along with creation.

Moving inward from the minimal answer is the position holding that what God has revealed in the economy is that there are three persons. This position refuses to specify further the identity of these three and remains satisfied with bare threeness itself. Relations among the three need not be specified, and the three need not be distinguished from each other. They are, in other words, potentially anonymous and interchangeable, perhaps undistinguished from each other even in themselves, but certainly in their revelation to us. If one sends and the other is sent at the economic level, this is not grounded in any actual relational distinction among them at the level of the eternal or immanent Trinity. Relationships of sending are considered to be not only below the line, but are considered as revealing nothing about what is above the line. Above the line is anonymous threeness, and below it is free divine action. “Sonship,” on this view, can be considered a messianic or salvation-historical characteristic, not attaching to the eternal second person but only taken on as this one takes up his mission and enters the economy.

If the “bare threeness” position is too minimal, the three can be said to be related to each other through eternal relations of authority: the first person sends the second because in eternity they are distinguished by personal characteristics of headship and authority. A Father is ordered over a Son, which is why the Father sends the Son.

The central position on this spectrum is the classic one, maintaining that the missions in the economy of salvation are revelatory of eternal relations of origin. Classic trinitarianism teaches that the Son and the Spirit proceed from the Father by two eternal processions. The sending of the Son, on this view, reveals that Son was always from the Father in a deeper sense than just being sent from the Father: he is eternally begotten. Nicene theology safeguarded this confession by distinguishing between the Son’s being begotten by the Father and the world’s being created by the Father through the Son. Just as “a man by craft builds a house, but by nature begets a son,” reasoned Athanasius, “God brings forth eternally a Son who has his own nature.”9 A parallel argument for the Spirit, that the Pentecostal outpouring is an extension of his eternal procession from the Father (with or without the filioque), completes the classic doctrine of the Trinity. On this view, the coming of the Son and the Spirit into our history is an extension of who they have always been. When the Father sends the Son into salvation history, he is extending the relationship of divine sonship from its home in the life of God, down into human history. The relationship of divine sonship has always existed, as part of the very definition of God, but it has existed only within the being of the Trinity. In sending of the Son to us, the Father chose for that line of filial relation to extend out into created reality and human history. Again, a parallel argument for the sending of the Holy Spirit completes the doctrine: at his outpouring, his eternal relationship with the Father and the Son begins to take place among us.

Moving from this classic central position toward the more maximal end of the spectrum, we could argue that relations of origin are not enough, and that the complex relationships that unfold among Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in salvation history must be the manifestations of a corresponding set of eternal relationships in the eternal divine life. On this view, not only do missions reveal processions, but economic destinations (“I go to the Father”) reveal eternal terminations, and temporal glorifications reveal eternal effusions. Many of these relationships are more obviously reciprocal than relations of origin. The Son comes from the Father, but not vice versa. However, the Son and the Father mutually and reciprocally glorify each other. Aware that he is recommending an innovation, Wolfhart Pannenberg argues that “the nexus of relations between [the persons] is more complex than would appear from the older doctrine of relations of origin . . . each is a catalyst of many relations”; indeed, each person is constituted by a “richly-structured nexus of relationship.”10 The crucial thing to note about this view is that it occupies a position from which classic trinitarianism seems too reserved in its affirmation about how much is revealed in the economy of salvation.

Further in the direction of a maximal interpretation of economic revelation is the view that what we have seen in the death of Christ does not stand in paradox to what God is in eternity, but instead stands as the revelation of the very being of God. On this view, Christ’s subjection to the conditions of human life, and especially his suffering and death, manifest the truth that God as such suffers. A variety of modern theologies since Moltmann have been drawn to a trinitarian version of theopaschitism.11 Again, for our purposes here it is only necessary to note how far this view is from the classical tradition in terms of its answer to the question of what is revealed in the economy: proponents of this view believe that more has been revealed than previous theologies have confessed.

This second task of the doctrine of the Trinity, the task of articulating the content of divine self-revelation, is where major doctrinal judgments are rendered. At stake here is the utterly fundamental issue of how we understand God on the basis of self-revelation in word and act. Having surveyed the spectrum of options and indicated how they relate to each other and to the classic formulations of the doctrine, we are prepared for some briefer remarks on the three subordinate tasks of trinitarian theology: ordering doctrinal discourse, identifying the Christian God, and regulating soteriology.

3. TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY ORDERS DOCTRINAL DISCOURSE

Trinitarian theology orders our doctrinal discourse simply by being such a vast doctrine. It is a field that encompasses many other fields of theology, most notably the doctrines of Christology and pneumatology. The health of a doctrine of the Trinity is a good indicator of the overall vigor of a theological system. Christology and pneumatology are each doctrines comprehensive enough to be treated as central and definitive areas; yet they require to be not only fully elaborated in their own right, but correlated with each other. The correlation of Christology and pneumatology with monotheism is not a bad description of the formal structure of trinitarian theology. Other sprawling doctrinal constellations or frameworks, such as the doctrine of revelation or the doctrine of salvation, likewise loom large in theology and are likewise to be subsumed and placed in the matrix of a well-articulated doctrine of the Trinity.

Since theology is primarily about God and secondarily about all things in relation to God, it stands to reason that the doctrine of God ought to occupy a determinative place in an overall doctrinal system. A theological system that takes its bearings from “theology proper” (that is, the doctrine of God) will be centered on, or dependent on, or (to vary the figure of speech again) located within the doctrine of God. When that doctrine of God is elaborated as a doctrine of the Trinity, the implications for the order of the entire system ought to be pronounced. John Webster has put this case sharply: “in an important sense there is only one Christian doctrine, the doctrine of the Holy Trinity in its inward and outward movements.”12 The implications for a rightly ordered theological system are that “whatever other topics are treated derive from the doctrine of God as principium and finis”; recognition of this is “crucial to questions of proportion and order in systematic theology. No other doctrinal locus can eclipse the doctrine of the Trinity” in its role of shaping theology as a whole.13 The doctrine of the triune God, in other words, shapes the entire outlook of theology and serves as the matrix for the placement and treatment of all other doctrinal loci.

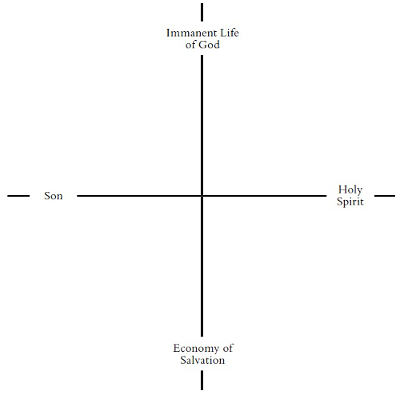

There are many possible ways of describing the relation of the trinitarian matrix to the other doctrines of systematic theology, especially as it forms the background of Christian thought. I have come to prefer a kind of theological Cartesian plane, or the intersection of two axes. Because God has made himself present to us and known to us in the Son and the Spirit, the first axis runs from God’s immanent life down to the economy, and the second runs between Son and Spirit. In other words, there is an immanent-economic axis crossed by a Christology-pneumatology axis.

The resulting quadrants establish the field of trinitarian theology, but they do more: they display the way that trinitarian theology orders other doctrinal discourse. The theological dynamics that generate the doctrine of the Trinity are those of God’s self-communicating presence on the one hand (vertical axis) and the two missions of the Son and the Holy Spirit on the other (horizontal axis). All Christian doctrines must in one way or another work themselves out in these same tensions, whether each doctrine is rendered explicitly trinitarian or not. Because this way of schematizing the doctrine is an attempt to depict the theological structuring forces of trinitarianism rather than to signify the Trinity itself (as triangular diagrams inevitably suggest), it has some helpful peculiarities. Using these quadrants to describe the Trinity, we could talk about the immanent Son and the economic Son, or the immanent Holy Spirit and the economic Holy Spirit. This enables us to discuss the personal identity of the Son and the Holy Spirit at either end of the immanent-economic axis (that is, in the top two quadrants and in the bottom two quadrants, respectively).

4. TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY IDENTIFIES GOD BY THE GOSPEL

The task of ordering doctrinal discourse follows rather directly from the primary tasks of summarizing the Bible’s story line and then articulating the content of divine revelation. Taken together, these three tasks imply a fourth task, one so normative and critical that it must have been accomplished simultaneously with them. The doctrine of the Trinity serves to identify God by the gospel, or to specify the identity of the God of Christian faith. It does so primarily by insisting that God is the author of two central interventions into the course of human history, the incarnation of the Son and the outpouring of the Spirit. These two actions, considered not in isolation but as culminating events, mark God as a particular God. The God who sent a Son and a Holy Spirit, because he always already had a Son and a Holy Spirit to send, must be essentially different from a God who could not and did not self-communicate in this way.

To say this is to treat the doctrine of the Trinity as a kind of name of God, as Robert W. Jenson has argued: “Thus the phrase, ‘Father, Son, and Holy Spirit’ is simultaneously a very compressed telling of the total narrative by which Scripture identifies God and a personal name for the God so specified.”14 Kendall Soulen’s recent book, The Divine Name(s) and the Holy Trinity, has championed and recovered the tetragrammaton, the actual revealed name of God, with such vigor that he has made it impossible to speak blithely about the trinitarian formula as the name of God without at the same time recalling the tetragrammaton as the one un-superceded, unrelativized name.15 But trinitarian doctrine continues to play its crucial role in identifying God by reference to the gospel. Lesslie Newbigin has argued that this function of trinitarianism comes to the fore especially in periods when Christian theology recalls that it cannot take the identity of its God for granted. Various periods of increased awareness of cultural diversity and pluralism have historically brought with them renewed attention to trinitarian theology: the fourth century, the sixteenth, and the late twentieth.16

5. TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY INFORMS AND NORMS SOTERIOLOGY

Finally, trinitarian theology plays an indispensable role in orienting the doctrine of salvation. We have already said as much in indicating the trinitarian background of all Christian doctrines, and how they must all be placed on the field of trinitarian discourse. But this function of informing and norming soteriology requires special attention, because it moves us from Christian theology to the Christian life.

For the Trinity to inform and norm soteriology is for the doctrine of the Trinity to give the shape and the material content and to dictate its parameters. The doctrine of salvation needs this sort of outside guidance if it is to maintain its balance between two besetting errors. The errors are of defect and excess, of not enough salvation on the one hand and too much salvation on the other. Trinitarian doctrine holds soteriology to the mean between them.

First, the error of defect: I have in mind a perennial tendency to minimize soteriology, to diminish it to something with no depth of ingression into the life of God. If soteriology is reduced to a lordship and obedience relationship, with forgiveness or sacraments as a way of patching up that relationship when it has been transgressed, then all the richness of the biblical language is flattened out or dumbed down; Christian sonship is merely metaphorical or analogous, and all the apostolic language of temple, courtroom, and family are interpreted as poetic ways of saying that God chooses to forgive or reconcile. A depth is missing here, and it is against this kind of reduction that so many modern trinitarians are reacting, under the slogan of Karl Rahner that many believers are “almost mere monotheists.” This minimal soteriology could be underwritten by a unipersonal God — almost by a deistic God, certainly by Allah. Trinitarian theology summons Christian soteriology to go deeper.

But not too deep. For at the opposite extreme is the error of excess. I have in mind here a style of soteriology that obliterates all distinctions between divinity and humanity, leaping over every barrier, beginning with that between creator and creature. Think of the Rhineland mystics who boasted of being “Godded with God and Christed with Christ,” but also of the way theosis (deification) is celebrated at the popular level, or schemes of ontological participation are championed in a variety of theologies.

When the doctrine of the Trinity is fulfilling its function of informing and norming soteriology, it rules out both extremes. John Calvin reminds us that “God, to keep us sober, speaks sparingly of his essence.” And yet the same Calvin, taking his norms from a trinitarian account of the adoption of believers by the Father in the only begotten Son by the Spirit of adoption, celebrates the depth and richness of the fellowship that is ours in Christ. God speaks sparingly of his essence, but lavishly of his Son and of our adopted sonship. A soteriology informed and normed by the doctrine of the Trinity equips us to recognize our intimacy with and our distinction from God in Christ. As Kevin Vanhoozer says, “Only the doctrine of the Trinity adequately accounts for how those who are not God come to share in the fellowship of the Father and the Son through the Spirit.”17 This too is a task of the doctrine of the Trinity, and it follows directly from the major and primary task of correlating the events of salvation history with the divine being in itself.

1. This object is held by the treasury of the Catholic church of St. Servatius in Siegburg, Germany. Contact info for the church’s treasury is: www.servatius-siegburg.de/kirchen-einrichtungen/einrichtungen/schatzkammer. Photo credit: Foto Marburg/Art Resource, NY.

2. I have described it this way in “The Trinity,” in The Oxford Handbook of Systematic Theology (ed. John Webster, Kathryn Tanner, Iain Torrance; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 35.

3. R. W. Dale, Christian Doctrine: A Series of Discourses (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1894), 151.

4. Ibid.

5. T. F. Torrance, The Christian Doctrine of God: One Being Three Persons (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1996), 6.

6. Karl Barth, CD I/1, 374.

7. John Webster, “Life in and of Himself,” in Engaging the Doctrine of God (ed. Bruce McCormack; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 123.

8. Austin Farrer, “Incarnation,” in The Brink of Mystery (ed. Charles C. Conti; London: SPCK, 1976), 20.

9. Athanasius, Contra Arianos 3.62.

10. Wolfhart Pannenberg, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 1:320.

11. Moltmann’s The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1974) was already quite far along the path of this sort of “trinitarian theology of the cross” (see 235 – 49), but The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1981) has been most influential.

12. John Webster, “Principles of Systematic Theology,” in The Domain of the Word: Scripture and Theological Reason (London: Bloomsbury/T&T Clark, 2012), 145.

13. Ibid.

14. Robert W. Jenson, Systematic Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 1:46.

15. R. Kendall Soulen, The Divine Name(s) and the Holy Trinity (Philadelphia: Westminster), 2011.

16. Lesslie Newbigin, The Relevance of Trinitarian Doctrine for Today’s Mission (Edinburgh: Edinburgh House Press, for the World Council of Churches Commission on World Mission and Evangelism, 1963), 32.

17. Kevin J. Vanhoozer, The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical-Linguistic Approach to Christian Theology (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2005), 43 – 44.