6

Study Strategically Using Long and Short Chunks of Time

Nothing can add more power to your life than concentrating all of your energies on a limited set of targets.

NIDO QUBEIN

School is a unique environment where you must learn a wide variety of subjects and skills. This is critical to your future success since the career you choose will require that you have many different types of skills and the flexibility to switch between them. You will need to know how to assess a situation and then find the best solution to the problem at hand.

In school, different skills require different methods of study. Some tasks are best accomplished in longer stretches of time, and some are better suited to shorter periods of focus. Learning how to tell which task is suited to which timeframe will vastly increase the effectiveness of your studying.

The Big Fish

Most of your large and important assignments will require longer chunks of unbroken time to complete. Your ability to carve out and use these blocks of high-value, highly productive time is central to your ability to make a significant contribution to your work and to your life. This sort of studying will have to be done on weekends or on evenings when you are able to dedicate significant time to your homework.

Successful students set aside chunks of time at least several hours long to work on major projects such as term papers, lab reports, experiments and research, or putting together college applications. These tasks require long, uninterrupted periods of time for you to make meaningful progress on them.

Schedule Blocks of Time

Many highly productive people schedule specific activities in preplanned time slots all day long. These people build their lives around accomplishing key tasks one at a time. As a result, they become more and more productive and eventually produce two times, three times, and five times as much as the average person.

When you have a weekend day or an evening with no externally imposed schedule, it is up to you to create your own schedule and then discipline yourself to stick to it. The key to the success of working in specific time segments is to plan your study time in advance and schedule a fixed time period for a particular activity or task. Chapter 19 has additional tactics for planning large chunks of study time in a manageable way.

Use a Time Planner

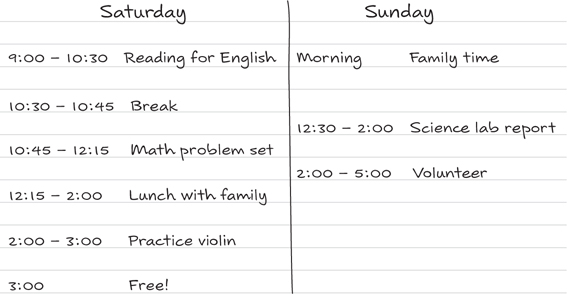

A time planner, broken down by day, hour, and minute and organized in advance, can be one of the most powerful personal productivity tools of all. It enables you to see where you can consolidate and create blocks of time for concentrated work. In the same way that your school gives you a schedule that says “9:00–9:50, 1st period, Math; 10:00–10:50, 2nd period, History,” you can create your own predetermined schedule for your unstructured time (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Weekend schedule

During these scheduled working times, turn off your phone and other devices, eliminate all distractions, and work for the whole duration of your self-structured plan. One of the best work habits of all is to get up early and tackle some tasks in the morning for two to three hours. You can get three times as much work done on a weekend morning when your friends are not yet up and it is not yet time for familial obligations.

The Many Small Fish

Working on large projects is not the only kind of learning you will be doing in school. School at any level is also about learning and retaining information permanently. To learn a large amount of information, such as historical facts and mathematical formulas, your brain needs to review the new information repeatedly over weeks or months. Learning new skills, like how to solve a differential equation or how to play an instrument, also requires repetition in the form of practice.

During weekdays your class schedule may take up most of your time, in high school, but this will also be true in college to some extent. Your schedule during the day is largely planned out for you. The time you have for homework may be scattered throughout that schedule in the form of a forty-five minute study hall or an hour and a half between two college lectures.

You should reserve specific kinds of studying for these shorter periods. Studying for a test is an example of something that you will need to do over and over in short bursts of time. Learning new information takes our brains a long time and demands repetition. This is why cramming for a test the night before will leave you with almost no memory of what you learned months or even weeks later.

Instead of cramming, you can decide to study for an upcoming test during a study hall (fig. 3), but choose just enough material that you can focus on for forty-five minutes. Don’t try to study all the material for the test or try to work on a term paper if you just have forty-five minutes. By the time you orient yourself and gather your thoughts to write, the period will be almost over.

Other good study hall tasks are reviewing flashcards for a foreign language class, reading a chapter of a book assigned for homework, and reviewing your notes using the learning methods you will see in chapter 15.

Figure 3. Study hall sample schedule

EAT THAT FROG!

EAT THAT FROG!

1.Think continually of different ways that you can save, schedule, and consolidate large chunks of time. Use these times to work on important tasks with the most significant long-term consequences.

2.Make every minute count. Work steadily and continuously without diversion or distraction by planning and preparing your work in advance. Most of all, keep focused on the most important results for which you are responsible.

3.Choose carefully which tasks to do based on how much time you have. Choose memory reinforcement for short periods of time, and focus on long-term projects when you have several hours to work.