CHAPTER TEN

You Can Run but Not Hide

If you carry your cell phone with you throughout the day, as most of us do, then you are not invisible. You are being surveilled—even if you don’t have geolocation tracking enabled on your phone. For example, if you have iOS 8.2 or earlier, Apple will turn off GPS in airplane mode, but if you have a newer version, as most of us do, GPS remains on—even if you are in airplane mode—unless you take additional steps.1 To find out how much his mobile carrier knew about his daily activity, a prominent German politician, Malte Spitz, filed suit against the carrier, and a German court ordered the company to turn over its records. The sheer volume of those records was astounding. Just within a six-month period, they had recorded his location 85,000 times while also tracking every call he had made and received, the phone number of the other party, and how long each call lasted. In other words, this was the metadata produced by Spitz’s phone. And it was not just for voice communication but for text messages as well.2

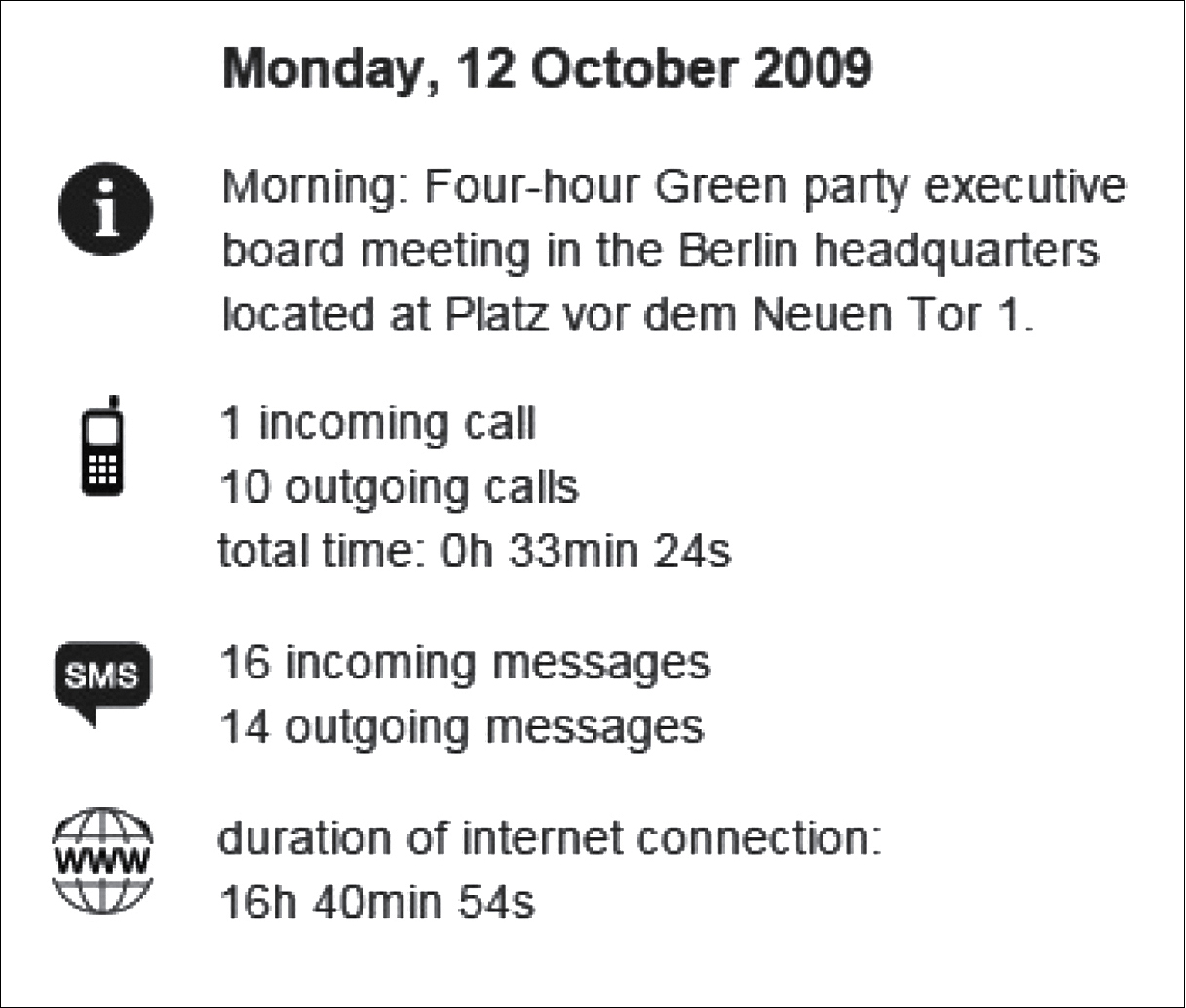

Spitz teamed up with other organizations, asking them to format the data and make it public. One organization produced daily summaries like the one below. The location of that morning’s Green Party meeting was ascertained from the latitude and longitude given in the phone company records.

Malte Spitz activity for October 12, 2009

From this same data, another organization created an animated map. It shows Spitz’s minute-by-minute movements all around Germany and displays a flashing symbol every time he made or received a call. This is an amazing level of detail captured in just few ordinary days.3

The data on Spitz isn’t a special case, of course, nor is this situation confined to Germany. It’s simply a striking example of the data that your cell-phone carrier keeps. And it can be used in a court of law.

In 2015, a case before the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit involved the use of similar cell-phone records in the United States. The case concerned two robbers who robbed a bank, a 7-Eleven, several fast-food restaurants, and a jewelry store in Baltimore. By having Sprint hand over information about the location of the prime suspects’ phones for the previous 221 days, police were able to tie the suspects to a series of crimes, both by the crimes’ proximity to each other and by the suspects’ proximity to the crime scenes themselves.4

A second case, heard by the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, didn’t detail specifics of the crime, but it also centered on “historical cell site information” available from Verizon and AT&T for the targets’ phones. In the words of the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed an amicus brief in the case, this data “generates a near-continuous record of an individual’s locations and movements.” When a federal judge mentioned cell-phone privacy during the California case, the federal prosecutor suggested that “cellphone users who are concerned about their privacy could either not carry phones or turn them off,” according to the official record.

This would seem to violate our Fourth Amendment right to be protected against unreasonable searches. Most people would never equate simply carrying a cell phone with forfeiting their right not to be tracked by the government—but that’s what carrying a phone amounts to these days. Both cases note that Verizon, AT&T, and Sprint don’t tell customers in privacy policies how pervasive location tracking is. Apparently AT&T, in a letter to Congress in 2011, said it stores cellular data for five years “in case of billing disputes.”5

And location data is not stored only with the carrier; it’s also stored with the vendor. For example, your Google account will retain all your Android geolocation data. And if you use an iPhone, Apple will also have a record of your data. To prevent someone from looking at this data on the device itself and to prevent it from being backed up to the cloud, periodically you should delete location data from your smartphone. On Android devices, go to Google Settings>Location>Delete location history. On an iOS device you need to drill down a bit; Apple doesn’t make it easy. Go to Settings>Privacy>Location Services, then scroll down to “System Services,” then scroll down to “Frequent Locations,” then “Clear Recent History.”

In the case of Google, unless you’ve turned the feature off, the geolocation data available online can be used to reconstruct your movements. For example, much of your day might be spent at a single location, but there might be a burst of travel as you meet with clients or grab a bite to eat. More disturbing is that if anyone ever gains access to your Google or Apple account, that person can perhaps also pinpoint where you live or who your friends are based on where you spend the majority of your time. At the very least someone can figure out what your daily routine might be.

So it’s clear that the simple act of going for a walk today is fraught with opportunities for others to track your behavior. Knowing this, say you consciously leave your cell phone at home. That should solve the problem of being tracked, right? Well, that depends.

Do you wear a fitness-tracking device such as Fitbit, Jawbone’s UP bracelet, or the Nike+ FuelBand? If not, maybe you wear a smartwatch from Apple, Sony, or Samsung. If you wear one or both of these—a fitness band and/or a smartwatch—you can still be tracked. These devices and their accompanying apps are designed to record your activity, often with GPS information, so whether it is broadcast live or uploaded later, you can still be tracked.

The word sousveillance, coined by privacy advocate Steve Mann, is a play off the word surveillance. The French word for “above” is sur; the French word for “below” is sous. So sousveillance means that instead of being watched from above—by other people or by security cameras, for example, we’re being watched from “below” by the small devices that we carry around and maybe even wear on our bodies.

Fitness trackers and smartwatches record biometrics such as your heart rate, the number of steps you take, even your body temperature. Apple’s app store supports lots of independently created applications to track health and wellness on its phones and watches. Same with the Google Play store. And—surprise!—these apps are set to radio home the data to the company, ostensibly just to collect it for future review by the owner but also to share it, sometimes without your active consent.

For example, during the 2015 Amgen Tour of California, participants in the bicycle race were able to identify who had passed them and later, while online, direct-message them. That could get a little creepy when a stranger starts talking to you about a particular move you made during a race, a move you might not even remember making.

A similar thing happened to me. On the freeway, driving from Los Angeles to Las Vegas, I had been cut off by a guy driving a BMW. Busy on his cell phone, he suddenly switched lanes, swerving within inches of me, scaring the crap out of me. He almost wiped out the both of us.

I grabbed my cell phone, called the DMV, and impersonated law enforcement. I got the DMV to run his plate, then they gave me his name, address, and Social Security number. Then I called AirTouch Cellular, impersonating an AirTouch employee, and had them do a search on his Social Security number for any cellular accounts. That’s how I was able to get his cell number.

Hardly more than five minutes after the other driver had cut me off, I called the number and got him on the phone. I was still shaking, pissed and angry. I shouted, “Hey, you idiot, I’m the guy you cut off five minutes ago, when you almost killed us both. I’m from the DMV, and if you pull one more stunt like that, we’re going to cancel your driver’s license!”

He must be wondering to this day how some guy on the freeway was able to get his cell-phone number. I’d like to think the call scared him into becoming a more considerate driver. But you never know.

What goes around comes around, however. At one point my AT&T mobile account was hacked by some script kiddies (a term for unsophisticated wannabe hackers) using social engineering. The hackers called an AT&T store in the Midwest and posed as an employee at another AT&T store. They persuaded the clerk to reset the e-mail address on my AT&T account so they could reset my online password and gain access to my account details, including all my billing records!

In the case of the Amgen Tour of California, riders used the Strava app’s Flyby feature to share, by default, personal data with other Strava users. In an interview in Forbes, Gareth Nettleton, director of international marketing at Strava, said “Strava is fundamentally an open platform where athletes connect with a global community. However, the privacy of our athletes is very important to us, and we’ve taken measures to enable athletes to manage their privacy in simple ways.”6

Strava does offer an enhanced privacy setting that allows you to control who can see your heart rate. You can also create device privacy zones so others can’t see where you live or where you work. At the Amgen Tour of California, customers could opt out of the Flyby feature so that their activities were marked as “private” at the time of upload.

Other fitness-tracking devices and services offer similar privacy protections. You might think that since you don’t bike seriously and probably won’t cut someone off while running on the footpath around your office complex, you don’t need those protections. What could be the harm? But there are other activities you do perform, some in private, that could still be shared over the app and online and therefore create privacy issues.

By itself, recording actions such as sleeping or walking up several flights of stairs, especially when done for a specific medical purpose, such as lowering your health insurance premiums, might not compromise your privacy. However, when this data is combined with other data, a holistic picture of you starts to emerge. And it may reveal more information than you’re comfortable with.

One wearer of a health-tracking device discovered upon reviewing his online data that it showed a significant increase in his heart rate whenever he was having sex.7 In fact, Fitbit as a company briefly reported sex as part of its online list of routinely logged activities. Although anonymous, the data was nonetheless searchable by Google until it was publicly disclosed and quickly removed by the company.8

Some of you might think, “So what?” True: not very interesting by itself. But when heart rate data is combined with, say, geolocation data, things could get dicey. Fusion reporter Kashmir Hill took the Fitbit data to its logical extreme, wondering, “What if insurance companies combined your activity data with GPS location data to determine not just when you were likely having sex, but where you were having sex? Could a health insurance company identify a customer who was getting lucky in multiple locations per week, and give that person a higher medical risk profile, based on his or her alleged promiscuity?”9

On the flip side of that, Fitbit data has been successfully used in court cases to prove or disprove previously unverifiable claims. In one extreme case, Fitbit data was used to show that a woman had lied about a rape.10

To the police, the woman—while visiting Lancaster, Pennsylvania—said she’d awakened around midnight with a stranger on top of her. She further claimed that she’d lost her Fitbit in the struggle for her release. When the police found the Fitbit and the woman gave them her consent to access it, the device told a different story. Apparently the woman had been awake and walking around all night. According to a local TV station, the woman was “charged with false reports to law enforcement, false alarms to public safety, and tampering with evidence for allegedly overturning furniture and placing a knife at the scene to make it appear she had been raped by an intruder.”11

On the other hand, activity trackers can also be used to support disability claims. A Canadian law firm used activity-tracker data to show the severe consequences of a client’s work injury. The client had provided the data company Vivametrica, which collects data from wearable devices and compares it to data about the activity and health of the general population, with Fitbit data showing a marked decrease in his activity. “Till now we’ve always had to rely on clinical interpretation,” Simon Muller, of McLeod Law, LLC, in Calgary, told Forbes. “Now we’re looking at longer periods of time through the course of a day, and we have hard data.”12

Even if you don’t have a fitness tracker, smartwatches, such as the Galaxy Gear, by Samsung, can compromise your privacy in similar ways. If you receive quick-glance notifications, such as texts, e-mails, and phone calls, on your wrist, others might be able to see those messages, too.

There’s been tremendous growth recently in the use of GoPro, a tiny camera that you strap to your helmet or to the dashboard of your car so that it can record a video of your movements. But what happens if you forget the password to your GoPro mobile app? An Israeli researcher borrowed his friend’s GoPro and the mobile app associated with it, but he did not have the password. Like e-mail, the GoPro app allows you to reset the password. However, the procedure—which has since been changed—was flawed. GoPro sent a link to your e-mail as part of the password reset process, but this link actually led to a ZIP file that was to be downloaded and inserted onto the device’s SD card. When the researcher opened the ZIP file he found a text file named “settings” that contained the user’s wireless credentials—including the SSID and password the GoPro would use to access the Internet. The researcher discovered that if he changed the number in the link—8605145—to another number, say 8604144, he could access other people’s GoPro configuration data, which included their wireless passwords.

You could argue that Eastman Kodak jump-started the discussion of privacy in America—or at least made it interesting—in the late 1800s. Until that point, photography was a serious, time-consuming, inconvenient art requiring specialized equipment (cameras, lights, darkrooms) and long stretches of immobility (while subjects posed in a studio). Then Kodak came along and introduced a portable, relatively affordable camera. The first of its line sold for $25—around $100 today. Kodak subsequently introduced the Brownie camera, which sold for a mere $1. Both these cameras were designed to be taken outside the home and office. They were the mobile computers and mobile phones of their day.

Suddenly people had to deal with the fact that someone on the beach or in a public park might have a camera, and that person might actually include you within the frame of a photo. You had to look nice. You had to act responsibly. “It was not only changing your attitude toward photography, but toward the thing itself that you were photographing,” says Brian Wallis, former chief curator at the International Center of Photography. “So you had to stage a dinner, and stage a birthday party.”13

I believe we actually do behave differently when we are being watched. Most of us are on our best behavior when we know there’s a camera on us, though of course there will always be those who couldn’t care less.

The advent of photography also influenced how people felt about their privacy. All of a sudden there could be a visual record of someone behaving badly. Indeed, today we have dash cams and body cameras on our law enforcement officers so there will be a record of our behavior when we’re confronted with the law. And today, with facial recognition technology, you can take a picture of someone and have it matched to his or her Facebook profile. Today we have selfies.

But in 1888, that kind of constant exposure was still a shocking and disconcerting novelty. The Hartford Courant sounded an alarm: “The sedate citizen can’t indulge in any hilariousness without incurring the risk of being caught in the act and having his photograph passed around among his Sunday-school children. And the young fellow who wishes to spoon with his best girl while sailing down the river must keep himself constantly sheltered by his umbrella.”14

Some people didn’t like the change. In the 1880s, in the United States, a group of women smashed a camera on board a train because they didn’t want its owner to take their picture. In the UK, a group of British boys ganged together to roam the beaches, threatening anyone who tried to take pictures of women coming out of the ocean after a swim.

Writing in the 1890s, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis—the latter of whom subsequently served on the Supreme Court—wrote in an article that “instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” They proposed that US law should formally recognize privacy and, in part to stem the tide of surreptitious photography, impose liability for any intrusions.15 Such laws were passed in several states.

Today several generations have grown up with the threat of instantaneous photographs—Polaroid, anyone? But now we have to also contend with the ubiquity of photography. Everywhere you go you are bound to be captured on video—whether or not you give your permission. And those images might be accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world.

We live with a contradiction when it comes to privacy. On the one hand we value it intensely, regard it as a right, and see it as bound up in our freedom and independence: shouldn’t anything we do on our own property, behind closed doors, remain private? On the other hand, humans are curious creatures. And we now have the means to fulfill that curiosity in previously unimaginable ways.

Ever wonder what’s over that fence across the street, in your neighbor’s backyard? Technology may be able to answer that question for almost anyone. Drone companies such as 3D Robotics and CyPhy make it easy today for the average Joe to own his own drone (for example, I have the DJI Phantom 4 drone). Drones are remote-controlled aircraft and significantly more sophisticated than the kind you used to be able to buy at Radio Shack. Almost all come with tiny video cameras. They give you the chance to see the world in a new way. Some drones can also be controlled from your cell phone.

Personal drones are Peeping Toms on steroids. Almost nothing is out of bounds now that you can hover a few hundred feet above the ground.

Currently the insurance industry uses drones for business reasons. Think about that. If you are an insurance adjuster and need to get a sense of the condition of a property you are about to insure, you can fly a drone around it, both to visually inspect areas you didn’t have access to before and to create a permanent record of what you find. You can fly high and look down to get the type of view that previously you could only have gotten from a helicopter.

The personal drone is now an option for spying on our neighbors; we can just fly high over someone’s roof and look down. Perhaps the neighbor has a pool. Perhaps the neighbor likes to bathe in the nude. Things have gotten complicated: we have the expectation of privacy within our own homes and on our own property, but now that’s being challenged. Google, for example, masks out faces and license plates and other personal information on Google Street View and Google Earth. But a neighbor with a private drone gives you none of those assurances—though you can try asking him nicely not to fly over your backyard. A video-equipped drone gives you Google Earth and Google Street View combined.

There are some regulations. The Federal Aviation Administration, for instance, has guidelines stating that a drone cannot leave the operator’s line of sight, that it cannot fly within a certain distance of airports, and that it cannot fly at heights exceeding certain levels.16 There’s an app called B4UFLY that will help you determine where to fly your drone.17 And, in response to commercial drone use, several states have passed laws restricting or severely limiting their use. In Texas, ordinary citizens can’t fly drones, although there are exceptions—including one for real estate agents. The most liberal attitude toward drones is perhaps found in Colorado, where civilians can legally shoot drones out of the sky.

At a minimum the US government should require drone enthusiasts to register their toys. In Los Angeles, where I live, someone crashed a drone into power lines in West Hollywood, near the intersection of Larrabee Street and Sunset Boulevard. Had the drone been registered, authorities might know who inconvenienced seven hundred people for hours on end while dozens of power company employees worked into the night to restore power to the area.

Retail stores increasingly want to get to know their customers. One method that actually works is a kind of cell-phone IMSI catcher (see here). When you walk into a store, the IMSI catcher grabs information from your cell phone and somehow figures out your number. From there the system is able to query tons of databases and build a profile on you. Brick-and-mortar retailers are also using facial recognition technology. Think of it as a supersize Walmart greeter.

“Hello, Kevin,” could be the standard greeting I get from a clerk in the not-too-distant future, even though I might never have been in that store before. The personalization of your retail experience is another, albeit very subtle, form of surveillance. We can no longer shop anonymously.

In June of 2015, barely two weeks after leaning on Congress to pass the USA Freedom Act—a modified version of the Patriot Act with some privacy protection added—nine consumer privacy groups, some of which had lobbied heavily in favor of the Freedom Act, grew frustrated with several large retailers and walked out of negotiations to restrict the use of facial recognition.18

At issue was whether consumers should by default have to give permission before they can be scanned. That sounds reasonable, yet not one of the major retail organizations involved in the negotiations would cede this point. According to them, if you walk into their stores, you should be fair game for scanning and identification.19

Some people may want that kind of personal attention when they walk into a store, but many of us will find it just plain unsettling. The stores see it another way. They don’t want to give consumers the right to opt out because they’re trying to catch known shoplifters, who would simply opt out if that were an option. If automatic facial recognition is used, known shoplifters would be identified the moment they enter a store.

What do the customers say? At least in the United Kingdom, seven out of ten survey respondents find the use of facial recognition technology within a store “too creepy.”20 And some US states, including Illinois, have taken it upon themselves to regulate the collection and storage of biometric data.21 These regulations have led to lawsuits. For example, a Chicago man is suing Facebook because he did not give the online service express permission to use facial recognition technology to identify him in other people’s photos.22

Facial recognition can be used to identify a person based solely on his or her image. But what if you already know who the person is and you just want to make sure he’s where he should be? This is another potential use of facial recognition.

Moshe Greenshpan is the CEO of the Israel-and Las Vegas–based facial-recognition company Face-Six. Their software Churchix is used for—among other things—taking attendance at churches. The idea is to help churches identify the congregants who attend irregularly so as to encourage them to come more often and to identify the congregants who do regularly attend so as to encourage them to donate more money to the church.

Face-Six says there are at least thirty churches around the world using its technology. All the church needs to do is upload high-quality photos of its congregants. The system will then be on the lookout for them at services and social functions.

When asked if the churches tell their congregants they are being tracked, Greenshpan told Fusion, “I don’t think churches tell people. We encourage them to do so but I don’t think they do.”23

Jonathan Zittrain, director of Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, has facetiously suggested that humans need a “nofollow” tag like the ones used on certain websites.24 This would keep people who want to opt out from showing up in facial recognition databases. Toward that end, the National Institute of Informatics, in Japan, has created a commercial “privacy visor.” The eyeglasses, which sell for around $240, produce light visible only to cameras. The photosensitive light is emitted around the eyes to thwart facial recognition systems. According to early testers, the glasses are successful 90 percent of the time. The only caveat appears to be that they are not suitable for driving or cycling. They may not be all that fashionable, either, but they’re perfect for exercising your right to privacy in a public place.25

Knowing that your privacy can be compromised when you’re out in the open, you might feel safer in the privacy of your car, your home, or even your office. Unfortunately that is no longer the case. In the next few chapters I’ll explain why.