![]() shin: heart, mind

shin: heart, mind

![]() shin: body

shin: body

![]() ren: drill, gloss, polish, practice, refine

ren: drill, gloss, polish, practice, refine

![]() ma: grind, improve, polish, scour

ma: grind, improve, polish, scour

Swallowing the field of vision

I am blind. Through me

Life sees.

![]() shin: heart, mind

shin: heart, mind

![]() shin: body

shin: body

![]() ren: drill, gloss, polish, practice, refine

ren: drill, gloss, polish, practice, refine

![]() ma: grind, improve, polish, scour

ma: grind, improve, polish, scour

We have seen how crucial observation and insight are to success in shugyo. A refined sensibility discerns beneath appearances, understands the significance of details, perceives the relationships between things, and senses underlying patterns and cycles. Without this refinement, progress is uncertain, and any power gained will prove self-destructive. Progress in training does not lie in acquiring technical skills alone nor in the acquisition of magical powers but in uncovering hidden aspects of natural being. One is then able to draw on these qualities, powers, and rhythms in training. Refining sensibility involves not only cultivating the mind and the senses but also attuning the body as an intuitive receiver. This complete cultivation is termed shinshin renma.

Patterns of unconscious behavior create blockages in body, energy, and mind. Each blockage reduces the capacity to access the natural powers within the self and the environment. At the same time, the ability to feel and register these same forces is cut off so that the blockage is unrecognized. The first step in overcoming frustration or stagnation is to recognize that the cause of such difficulties lies in one’s own ignorance—that something is being missed.

Neuroscience has demonstrated that seeing is not the mechanical process it was once assumed to be. The mind modifies the image received by the retina in many ways and at many levels. “Visual attention” is the term given to the first level of interference by which the mind registers only parts of the complex image presented to it. On deeper levels the mind has the capacity to distort this information further. To a great extent, it only sees what it wants or expects to see. This distortion occurs with all the other senses, including the “inner” senses that convey to us kinesthetic information like the relative position of limbs, tone of muscles, and direction of movement. The strength of these distorting mechanisms lies in the reluctance of the mind to change habitual ways of operating.

This mental resistance is often strongest in those who persist in the martial arts. Paradoxically, the same willpower that allows someone to endure where others would give up prevents them benefiting from their efforts. On rare occasions, sheer intensity of training can trigger a crisis and a revelation. However, such breakthroughs always come at a price—if not serious injury, then a reduction of life force and longevity. Conscious cultivation is therefore infinitely preferable.

As we have noted several times, one cannot recognize something one does not, in some measure, possess. Those with physical gifts are comfortable in their bodies and enjoy exercising them but often lack interest in mental endeavors. Intellectuals are at ease in a world of abstract ideas but are often incompetent when interacting with the physical world. The emotionally driven peer through a haze of projected feelings. Those who crave power see nothing but opportunities for self-advancement. Spiritual “seekers” often outdo all others in their blindness by rejecting everything outside a narrow conception of holiness.

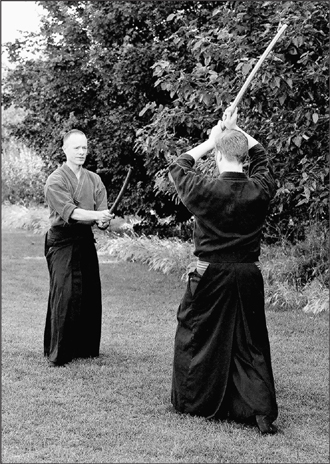

Figure 17. Cutting with the eyes

This obtuseness leads to lack of progress, confusion, stupor, obsessiveness, impetuous behavior, accidents, and injuries. Crucially for a practitioner of martial arts, it will result in a disadvantage when facing an opponent. The term seigan kamae (literally, “exact or correct eye guard”) is frequently used instead of chudan kamae to describe the standard combative posture. The omote (surface) meaning of seigan kamae is to point one’s sword exactly at the opponent’s eyes, and in some schools the chudan position is modified accordingly.1 The ura (hidden) meaning of seigan is that one’s seeing is without defects. In order to detect weaknesses and opportunities for attack (suki), one must see the opponent clearly and in his or her entirety.

Seigan kamae unifies several ways of seeing—focused vision (metsuke), peripheral vision, internal awareness, and projection of seme (assertive life force). All are admirably expressed in the combative stance of Agyo (see chapter 3). A kamae does not exist in isolation. It is a stance assumed in relation to an adversary, not a physical shape but a total tuning into a situation. One “sees” through the sword and the body as well as with the eyes.

According to Mikkyo, perception involves an exchange of many kinds of energies, not just the processing of sensory data. In Mikkyo (and its Indian antecedents) all phenomena throughout the cosmos and within the individual are termed dharma and are considered forms of primordial energy. One of the attractions of the Mikkyo system to those who practice complex disciplines is the way in which it helps to structure and clarify categories of object and levels of action. This is especially useful to those who are more interested in assessing the results of practical endeavors than in philosophical conjecture.

Central to the Mikkyo model are the Godai2 or five “Greats”—Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space (or void). These elements have been used to describe the different qualities, functions, and stages of development in many arts and disciplines. The best-known example of this is the Gorin no Sho of Miyamoto Musashi, in which he arranges his five chapters under the headings of the Godai.

The most sophisticated description of the relationships between the many dharmas and principles underlying them is to be found in the matrix mandala (Taizokai) of Shingon Mikkyo. One such important relationship is that between the five elements and the five ways of perceiving (Gochi). These ways of perceiving are inseparable from their originating elements. If an element is not expressed in the body of the practitioner, the associated way of perceiving will be inaccessible no matter how much mental training is undertaken. When the expression of these elements is blocked, the Gochi are distorted and manifest instead as the Gosho, the five poisons or afflictions.

To take the example of the first element, actions with Earth qualities manifest grounding. This requires the release of all tension downward through the acceptance of the effects of gravity. Power is then built up from the ground and projected out through the limbs. Sword techniques of this level involve deep stances and large, full swings. Power is returned to the center and reabsorbed back into the ground. The sequence of movement is feet first, then body, and finally sword. The energy that governs grounding is termed apana in Sanskrit, and for its full functioning, the legs must be flexible and powerful enough so that circulation is maintained even when low stances are held for prolonged periods. When one can stay relaxed in the deep horse stance for five minutes, the connection between this physical position, the descending energetic current, and equality of awareness will be self-evident. The mind is released of all projections, peripheral vision spreads, and internal awareness permeates the tissues.

| Element | Wisdom | Poison |

| Earth | equality | pride |

| Water | mirror-like | hatred |

| Fire | discriminating | desire |

| Air | all-accomplishing | envy |

| Space | all-accommodating | ignorance |

A fuller account of these associated qualities, particularly as they relate to swordsmanship, is given in appendix II.

Earth is the foundation for the other elements, and although Earth techniques are rarely applicable in kumitachi, facility in them is necessary to master techniques of succeeding levels. Even if a student has fiery qualities such as explosive body movement and sharp discernment of detail, unless Earth and Water are fully present, these strengths will be flawed and unreliable. Lacking Earth, their explosive movements will be unstable; lacking Water, the actions of the limbs will be uneven, resulting in misjudgment and injury. On the level of observation, they will be quick to snatch at isolated signals from the opponent and react to them. In this way they are driven by the affliction of desire. The Mikkyo approach to these afflictions is to recognize them as inappropriately expressed energies and devise strategies to trigger the latent qualities that will balance them.

The most important part of renma takes place not during one’s own practice but while watching the training of others. As a calligrapher reveals himself on the page through his brushwork, so the sword moving in space magnifies the qualities and defects of the swordsman. A teacher’s duty in this regard is to demonstrate techniques in a number of ways so as to highlight the presence or absence of elemental qualities. Even the most obtuse observer will begin to awaken to what they are missing when they see the stark difference, for example, between a kata performed with excess of Earth and then with excess of Water. Once this realization begins, watching the excesses and deficiencies of one’s peers will also be beneficial.

An experienced eye can judge the level of ki-ken-tai-ichi from the relationship between the sword and the body in movement. At the Earth level, the body stabilizes and then projects the sword; at the Water level, the sword moves and the body follows fluently, staying close to the ground. At the Fire level, the sword and body move explosively and simultaneously in bursts of action from the center. At the Air level, the body and sword move effortlessly and instantaneously in three dimensions wherever the mind directs. Actions of the Space level are as hard to recognize as they are to achieve, since they are spontaneous and originate from the core of being, beyond the scope of the conscious mind.

Although this fifth level cannot be taught, the first four elements are clearly present in many traditional kata, and their qualities can be elucidated by a skillful teacher. However, specific kata derived from each of the first four levels are the most powerful teaching tool. I was fortunate to begin my training with a syllabus ordered according to the hierarchy of the elements and to train for many years in another discipline that shares this elemental approach. Training in this way, one begins to recognize the dominance of one element through the appearance of the mindset, movement quality, rhythm, posture, or energetic pattern characteristic of that element.

Each element predominates in a different part of the body (see appendix II) and also governs certain functions throughout the body by means of the energetic system. In chapter 3 we noted the subtle adjustments required to make tanren effective. During the slow movements and static positions of tanren, the cultivated mind begins to recognize the sensations of different currents or “winds” at work in the body. When this sensitivity is gained, tanren is the most effective way to break through long-standing blockages and overcome chronic injuries.

Musashi concludes the Earth chapter of Gorin no Sho with ten principles, including the following:

Become familiar with all the arts.

Know the Ways of all professions.

This may seem like an unnecessary if not impossible task for the swordsman, considering the already considerable demands of mastering the art of the sword. The point here is that the study of other arts will deepen and broaden one’s understanding of one’s own art (as one begins to penetrate the elements common to all). Sometimes it is easier to see what is cut off in one’s own art through participation in a different activity in which one has not yet formed fixed habits.

Bushi, the elite samurai, were exposed to many crafts and arts in everyday life. They developed a sophisticated appreciation of the aesthetic and functional qualities of their weapons, armor, and clothing as well as the carefully constructed environments of house and garden. Their sensitivity to the natural world was heightened by spending much of their time outdoors and by their exposure to literature that evoked seasonal rhythms and natural beauty. The samurai was also expected to maintain and repair his equipment himself. Similar duties formed a large part of my early training in Japan; I carved bokken and tanrenbo, ground and filed vajras and kabutowari, made training clothes, and constructed various pieces of equipment for training or mountain camping. When specialist skills were called for, I was introduced to the appropriate craftsmen and worked with them to design what was needed.

Noting a lack of enthusiasm in practical matters (compared to my appetite for physical training or scholarship), my teacher devised a singular method of training for me. This would begin on the ground floor of a department store in the city. We would slowly work our way up through all the departments while I was bombarded with a continuous stream of questions about items we came across—their origin, method of construction, aesthetic qualities, appropriateness to the different seasons, and utility. This would go on relentlessly for hours until I experienced a fatigue (bodily and mental) unlike anything I had experienced before. Over time these days grew more intimidating than the hardest mountain training. Eventually I realized that this “department-store training” engendered such exhausting resistance because it confronted my disdain for the mundane and anything I did not consider “spiritual.”

One day I recognized that same fatigue during one of the regular kumitachi sessions in which my teacher would repeatedly change weapons and ask me to select an appropriate weapon from the loaded racks to counter his choice. He made it clear that my inability to choose or adapt to the use of this succession of weapons arose from the rigidity of my mind.

It was continually drummed into me that martial disciplines and shugendo were only kept alive so long as such testing was maintained as an integral part of their practices. In the age of dojoyaburi, when wandering swordsmen would challenge the masters of other schools, all styles were subject to continuous testing and adaptation. He lamented that after generations without such testing, many schools had been reduced to skeletons or empty shells.

A little theoretical knowledge is a dangerous thing, and a lot can be ruinous if it is not integrated with other activities. As their name suggests, the bushi (cultured warriors) sought that integration and gave it an importance enshrined in the samurai motto “bunbu ichi”—“literary and martial are one” (an interesting contrast with the English adage “the pen is mightier than the sword”). For similar reasons the elite samurai were also referred to as bugeisha, the practitioners of bugei (martial ways and the arts).

The samurai’s literary cultivation was in part the natural outcome of studying the Japanese language. The writing of kanji demands a draftsman’s eye and dexterity. To brush the strokes well the body must be centered, the hand relaxed and supple, and one must combine a keen appreciation for detail with an awareness of overall balance.3

Many kanji have a wealth of possible meanings as well as a unique shape or group of shapes, often with their own associations. These kanji can therefore be easily assembled to form words of subtlety and rich ambiguity. The precision and fluidity of mind this language develops is well suited to the composition of poetry and the expression of philosophical insight. This profundity is clear in the Confucian classics, including the divinatory Book of Changes, and the core texts that set out a philosophy of spiritual discipline, duty, and social harmony; these texts were considered essential reading for the samurai. Given this rich education, it is not surprising that many bushi took an interest in Taoist and Buddhist teachings, including Mikkyo.

The insight and wisdom engendered by this culture, when combined with a shugyo in kenjutsu, is revealed in the writings of swordsmen like Miyamoto Musashi, Yagyu Munenori, and Yamaoka Tesshu. Although one can obtain good translations of works by these men as well as spiritual masters like Takuan or Kukai (the Shingon patriarch), the modern mind is ill-equipped to make use of the knowledge they contain. Discriminative powers are essential, and yet these writings are designed to take the mind to a place the analytical mind cannot follow. Only by penetrating the meaning of such texts through careful reading and rereading, together with continued efforts to test one’s understanding in a practical art, can this knowledge be of any use. One should concentrate on one or two primary sources and memorize important terms and key passages so that they become part of one’s own vocabulary.

The ideal of complete and perfect vision in Japan is personified in the bodhisattva Kannon (see color insert this page), sometimes described as the bodhisattva of compassion. (Kan refers to a deep seeing into the “heart of things”; on refers to the cries of suffering beings.) This deity plays a central role in the Taizokai mandala. Like Fudo Myo O, Kannon also has a particular significance for both practitioners of shugendo and bugei. (Tesshu had a particular devotion to her, and Musashi dedicates his Gorin no Sho to her.) In one of her best-known forms Kannon is depicted with a thousand eyes and a thousand arms. The many eyes allow her to discern the unique suffering of all beings, and the arms, each holding a different ritual object, represent her ability to assist each in a unique and appropriate way. These attributes indicate her infinite capacity to see and to act.

The Heart Sutra, the most commonly chanted sutra in Japan, begins by describing the wisdom that Kannon has found in deep meditation and uses the name Kanjizai Bosatsu—the bodhisattva who freely sees. As we have seen in the depiction of the five wisdoms, freedom to see is the outcome of freedom from attachment to any one element and leads to the freedom to act. Freedom from attachment does not come from withdrawing from the world but from opening oneself up to its totality through one’s chosen sphere. Paradoxically, the very process of training in satsujinken (the killing sword) leads inescapably to katsujinken, the life-giving sword, if the crucial goal of attaining complete knowledge of the opponent is followed to its end. The devotion to Kannon is no sentimental affectation but the recognition that she embodies the state of ultimate awareness that is the heart of seigan kamae.

Figure 18. Seigan kamae

1. In the Nakamura Ryu kumitachi kata, when uchidachi changes from chudan to jodan kamae or hasso kamae, shidachi tilts the sword and slightly extends the tip forward and upward to point directly at the opponent’s left eye (see figure 18).

2. The Godai played an important part in many religions, philosophies, and practical systems in India and Ancient Greece. They should not be confused with and cannot be usefully integrated with the Gogyo—the cycle of changes. The Gogyo is a cornerstone of Chinese philosophy and is a model of energetic cycles that has also been utilized in many Chinese and Japanese martial arts systems.

3. Not only do the same principles apply to swordsmanship, but the eight basic brush strokes exactly mirror the eight basic sword cuts. Recognition of this parallel inspired Nakamura Taisaburo Sensei to create the happo giri system of Nakamura Ryu. In China as well as in Japan it was assumed that sword masters would be skilled calligraphers.