Perhaps the best place to start in Deaf history is at the beginning of mankind, as researched by scientists. About four million years ago, human-like animals called australopithecines1 appeared on Earth. They walked differently than we do and had smaller brains. Without any recorded history of deaf people—none of the hieroglyphics discovered by archaeologists ever mentioned any incident of hearing loss or deaf people—we are left with several potential situations.

During those times, it was a survival-of-the-fittest environment; each person had to fend for himself. It’s likely that children born with disabilities or deformities were killed or abandoned. Still, it wouldn’t be surprising if deaf people survived, given that hearing loss is often overlooked.

Deaf people often jest that the first sign or gesture was for “come here.” Another possible first gesture could have been using the index finger to point at things. Deaf children are often told that it is impolite to point at people or things, but hearing children also use this gesture for a variety of reasons; they most certainly did not invent this gesture.

Gordon Hewes, Ph.D., an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, suggested that signs were probably the first language and that signs helped humans to start voice languages. He added that sign languages probably made voice language possible.2 Eventually gestures and sounds were used to identify people, places or things. As thousands of years passed, people used fewer and fewer gestures, with their grunts eventually evolving into speech to communicate desires or ideas.

The earliest history of mankind was recorded through tools and crafts created from iron and bronze. In 4000 B.C., physical strength and manual skills were considered significant. It has been theorized that writing started during the Sumerian civilization (circa 5000 B.C.), when people drew pictures on wet clay. The clay, later sun dried, was used to communicate or record events. Eventually drawings got smaller and smaller; small drawings were then made into a form of symbols.

Based on the earliest known written records, it appears that attitudes toward deaf people and people with other disabilities were partly positive and partly negative.3 In ancient Greek society, if a disabled or deformed child was born into a family, the father had the authority to decide whether or not the child would live. Hebrews and Egyptians, however, had significantly different perspectives.

The Egyptians treated disabled persons with respect; in fact, in Egypt, blind men often became musicians. The first mention of a deaf person, Chushim, is noted in the Torah. The Torah tells of how Chushim killed his grandfather Cain and was praised. The Hebrews considered disabilities as a fact of life, part of God’s creation. Although deaf people were considered “legally incompetent,” they could be taught and were therefore not idiotic. If they could not speak, they were not considered legally competent, although they might communicate via writing. It has also been observed in the Talmud, or Jewish religious writings, that deaf persons were not allowed the right to own property.4

Jewish scripture dictated that it was necessary to hear speech so that a person could understand and obey the Lord. Isaiah 28:23 states, “Give ye ear, and hear my voice; harken, and hear my speech.” Sympathetic attitudes toward deaf people (and blind people) were noted when the Lord offered Moses a set of several laws. Leviticus recorded one of them, which reads: “Do not curse deaf people or put a stumbling block in front of the blind, but fear your God. I am the Lord” (Leviticus 19:28).

The ancient Hebrews may have been the first to distinguish between born-deaf people and those who lost their hearing later in life.5 Although literature does not show the distinction as “prelingually deaf” and “postlingually deaf,” as is said today, Hebrews said that those born deaf could not own property. Furthermore, those born deaf were perceived by hearing people as easily tricked and thus treated like children by society at large. Those who lost hearing later, especially those who could not understand language through hearing and did not speak, were given certain rights; those who could speak were bestowed with more rights and were better accepted by Hebrew society.6 Even though the Hebrews were kind to deaf people, they did not allow deaf people to participate fully in Temple rituals.

Two early Greek historians mention a deaf man believed to have lived from 600 to 550 B.C.7 No name is given, but he was a son of Croesus, King of Lydia. The king is believed to have said that Atys, his other son who was hearing, was his only son; the deaf son was considered lost. Atys built a reputation for himself, became as famous as his father, and was next in line for the throne. However, he met an accidental death when his friend impaled him with a spear while trying to kill a boar.

There are two versions of what happened to the deaf son. Herodotus, who wrote the story of the two sons a century later, mentioned that Croesus’s army fought Persians to increase his empire. The deaf son, in seeing a Persian soldier rushing toward his father, yelled out, “O man, do not kill Croesus!” He was able to speak for the rest of his life. The other version, written by Xenophon in Cyropaedia, portrayed Cyrus taking Croesus prisoner. Croesus was said to tell Cyrus that he had two sons, but “they have been of no good to me, for one remained mute, and the other died in the flower of youth.”8 Croesus was no longer a king, so his deaf son did not inherit his father’s crown.

The Greek philosopher Socrates in the fifth century B.C. appears to have been the first person to write about sign language. Apparently fascinated by it, he inquired of his colleague Hermogenes: “Suppose that we had no voice or tongue, and wanted to indicate objects to one another, should we not, like the deaf and dumb, make signs with the hands, head and the rest of the body?”9 Hermogenes replied, “How could it be otherwise, Socrates?” This illustrates that deaf people existed then, and were accepted by Greek society.10

Another famous Greek philosopher, Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), was a pupil of Plato, who learned under Socrates. Aristotle apparently disagreed with Socrates when the former wrote in 355 B.C., “Men that are deaf are also speechless; that is they can make vocal sounds but they cannot speak.” He was also recognized with producing the quotation: “Those who are born deaf all become senseless and incapable of reason.” Because Aristotle believed that hearing contributed the most to intelligence, and that thought could be expressed through the medium of articulation, he was, for the next two thousand years, accused of oppressing deaf people. On the other hand, it has been said that he was quoted out of context. Apparently he was referring to the fact that a deaf child, born deaf, would not learn to speak or express himself without special training.11

Christianity first records philosophical acceptance toward deaf people around A.D. 30.12 Although the church excluded deaf people from church membership, its benevolent attitude benefited these people. The Bible mentions the word “ephphatha,” uttered by Jesus Christ who healed a “deaf and dumb” man. Mark 9:25 in the New Testament reads:

Aristotle, Intelligence and the Deaf. © 2003 Dan McClintock.

They brought to him a man who was deaf and had an impediment in his speech, with the request that he would lay his hand on him. He took the man aside, away from the crowd, put his fingers into his ears, spat, and touched his tongue. Then, looking up to heaven, he sighed, and said to him, “Ephphatha,” which means, “Be opened,” and at the same time the impediment was removed and he spoke plainly.... [The people said] “He even makes the deaf hear and the dumb speak.”

One of the more fortunate deaf individuals was Quintus Pedius, whose name first appeared in history books around A.D. 77. Quintus’ grandfather requested permission from Emperor Augustus Caesar for Quintus to study to become an artist. The fact that his grandfather was in a position of influence as a consul of the emperor probably played a vital role in Caesar’s approval. At that time, deaf children born of prominent parents had more opportunities than those born into lower classes within the Roman caste system.13 Subsequently, Quintus was considered one of the most eminent painters of Rome.14

Christians believed that Jesus had magical powers through God and could perform miracles. Yet deaf people were excluded from church membership, primarily based on Romans 10:17: “So faith comes from what is heard.” Christians also believed that deaf people were not able to confess their sins. Saint Augustine is often credited with the view that Deaf people could not be saved because they were not able to hear the word of God. The New Testament suggested that deafness was caused by an evil spirit and deaf people could not become Christians.15 Perhaps Augustine was merely following his church’s doctrine when he commented that deafness was a hindrance to faith. Later, he became more optimistic when he disclosed that deaf people could learn and thus were able to receive faith and salvation.

During the Dark (Middle) Ages, humans faced difficulties such as poverty, famine and diseases. As a result, there were not many advances in arts and sciences. Painters worked mostly on religious subjects.

During the early part of the Middle Ages, deaf adults were objects of ridicule and even served as court jesters. Others were committed to asylums because of their lack of speech or because their behaviors were thought to be the result of demonic possession. During the late Middle Ages, the Christian church viewed deaf people as heathens and barred them because they were unable to hear the word of God. Deaf people, in the church’s eyes, lacked faith and thus could not be saved.16

During the sixth century A.D., Romans recognized deaf people who could not speak as a group that required special attention and protection. Interestingly enough, the Romans were careful in categorizing various types of deafness. Similar to the ancient Hebrews, the Romans noted the differences between those who lost hearing at birth and those who lost their hearing later on. Roman Emperor Justinian was a Christian and one of the most influential men of the early Middle Ages. In A.D. 528, the Justinian Code,17 created during Justinian’s reign, classified deaf people into five categories:

1. The Deaf and Dumb with whom this double infirmity is from birth;

• Forbidden the right to control their property

• All purchases and sales had to be arranged through a guardian.

• Can’t make wills, build properties, or free slaves

2. The Deaf and Dumb with whom this double infirmity is not from birth, but the effect of an accident that occurred during life;

• Could have all privileges returned to them if they were able to communicate in writing

• Are educable, can be taught, mainly in art or painting

3. The Deaf person who is not dumb, but whose deafness is from birth;

• Could be what we call today “hard of hearing” (speech is not perfect, but still can speak)

• May function and think like hearing persons, depending on the hearing loss

4. The person who is simply deaf, and that from accident;

• Because s/he still uses speech, s/he follows the social and legal status that hearing people enjoy.

5. Finally, he who is simply dumb, whether born dumb or became dumb.

• Simply put, this person is mute.

• If can read or write, then follow the 2nd classification.

In order to survive, deaf people during that period had to depend on their parents’ wealth, on working in important positions, and on their educational status (especially the boys). Otherwise, they were rejected, neglected, or abandoned.

However, during the Middle Ages, interest in teaching deaf people grew. The earliest medieval efforts at instructing deaf people were always sparked by religious zeal to provide salvation of the souls of deaf people. In 685, during Lent, a disheveled young deaf man was brought to the Bishop of Hagulstad in England. The bishop taught him the alphabet, then progressed to syllables, whole words and then whole sentences. The young man was also taught to speak. Modern-day scholars have questioned the validity of being able to learn to speak well in a short frame of time. However, the bishop, then St. John of Beverly, is today the Patron Saint of Teachers of the Deaf.18

Monks, as a source of information, preserved and shared some of their writings about deafness. Benedictine monks invented a system of signs and fingerspelling to circumvent “vows of silence.” These signs may have been used later in attempts to teach Deaf children.

Physicians in those days considered deafness a malady and a physical condition that should be eliminated to allow a healthy life. Deaf people endured numerous experiments in the search for a cure for deafness, such as the blowing of a trumpet in the ears or pouring liquids (oil, honey, vinegar, bile of rabbits or pigs, garlic juice, goat’s urine, eel fat mixed with blood) into the ears.

The Renaissance was a time of great change and rebirth in religion, astronomy, literature and art. During this rebirth and growth, deaf people were recognized as people of abilities. They were taught to read and write, and they were able to express themselves.

A comment on teaching a deaf child was noted in the book De Inventione Dialectica (On Dialectical Invention), by Rudolph Agricola (1443–1485), a Dutch author. He described a deaf-mute who was taught to read and write. The book was not published until 1521, 36 years after his death.

Italian physician Dr. Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576) discovered Agricola’s story and was impressed by the achievement of the deaf man. Cardano’s firstborn son was deaf, and Cardano happened to focus on the eyes, ears, mouth, and brain in his medical practice. He reasoned that written words were independent of the sounds of speech; thus deaf people could understand and be taught without aural references. He theorized that a deaf individual might be taught to “hear” by reading and to “speak” by writing.19 Cardano also recognized deaf people’s ability to use reason. American professor Dr. Ruth Bender, in her book, called Cardano’s findings “a revolutionary declaration,”20 thus breaking down the long-standing belief that the hearing of words was necessary for the understanding of ideas.

During the Renaissance, because so much intermarriage in the Spanish royal families took place, a fairly large percentage of children were born disabled or deaf. Since there still were no schools for the deaf in Spain, wealthy families sent their deaf children to monasteries or convents or hired tutors for them.

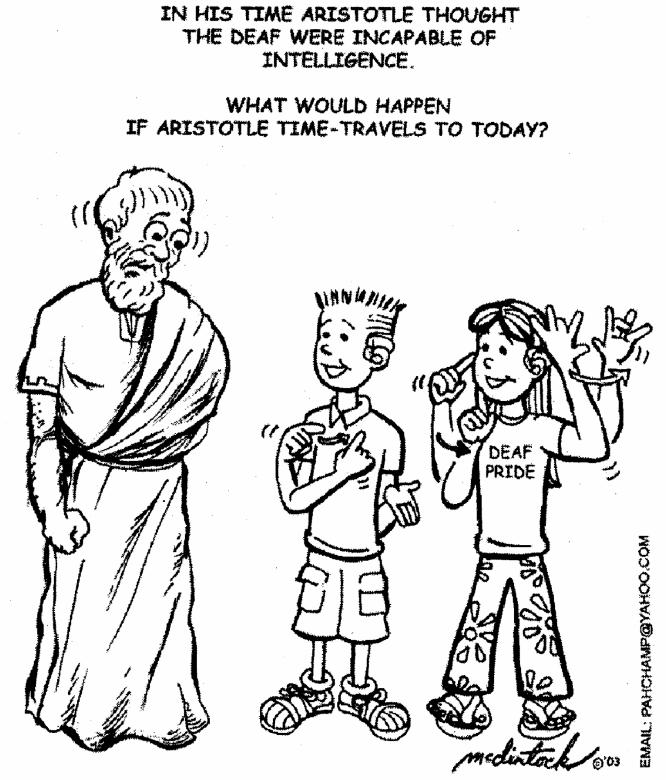

Ponce de Leon (1520–1584), a Spanish Benedictine monk, taught deaf people at a monastery, with an emphasis on speech. His students included Gaspard Burges, who learned to read and write there. At that time, tightly knit families of the noble and upper-middle classes tended to keep their conquests and hold their wealth within the families, usually through intermarriages. The de Velascos were one of Spain’s most powerful families. Juan de Velasco and Juana Enriquez were blood relatives and had nine children, four of them deaf. Two older deaf daughters entered separate convents. Their father, seeking a teacher for his two deaf sons, was referred to a nearby monastery where de Leon, already known for his success with Burges, resided. There, the two younger male siblings were taught to read and write so that they could legally inherit their family’s property and status.

De Leon first taught objects’ written names, then their pronunciations, and then the words were practiced in association. The two brothers, Pedro and Francisco de Velasco, learned well the skills of reading and writing, and they also were said to have learned to speak. Both eventually assumed their full responsibilities as noblemen. According to Scouten,21 de Leon was the first bona fide teacher of the deaf. Carved on his tombstone is the epitaph: “Pedro Ponce educated the deaf and dumb though Aristotle declared it impossible.”22

In the 1500s, deaf artist Juan Fernandez X. Navaretta was known as El Mudo, Spanish for “the mute one.” He was a very talented artist who could read and write. When King Philip II saw Navaretta’s painting of Christ’s baptism, he hired El Mudo as a court painter, a high honor.23

In 1575, the Spanish lawyer Lasso denounced an old belief that being deaf automatically meant a lack of intelligence. He also announced that deaf people should have the right to bear children.24

During the seventeenth century, the opportunities for learning were greatly expanded for deaf children. Again, the fortunate deaf children were usually born of royal bloodlines or had connections to royalty.

After de Leon’s death, Spanish educators Juan Pablo Bonet and Manual Ramirez de Carrion carried on his work. In 1612, two-year-old Luis de Velasco lost his hearing due to high fever. He was the son of widowed Doña Juana de Córdoba. Incidentally, he was the grandnephew of the two aforementioned brothers, Pedro and Francisco de Velasco. Bonet, a long-time secretary to the family, recalled hearing about the successful learning of the two brothers. After a search, Bonet located an articulation teacher, Ramirez de Carrión. De Carrión had served as a tutor and secretary to a deaf man, Marquis de Priego, in Montilla. Nothing has been written about de Priego, but apparently, able to afford a private tutor, he was a rich and successful man. Bonet struck an agreement with the Marquis to release de Carrión for three to four years so that de Carrión could teach Luis.

De Carrión worked with the deaf boy for four years. One can assume that Luis’ knowledge of speech before becoming deaf facilitated his learning and the recovery of his ability to talk. At the age of nine, Luis had basic skills in reading, writing, and speaking Spanish. During this time, Bonet observed de Carrión’s work with Luis and recorded the events. Subsequently, Bonet wrote a book on de Carrión’s practices and added his own theories of teaching deaf children. He asserted that deaf children could be taught through the eyes by learning letters in print and manual alphabet and then learning to lipread by copying the teacher’s use of lips for consonants, vowels, words, and sentences.25 The book, The Simplification of Letters and the Art of Teaching the Mute to Speak, published in 1620, is said to be the most influential book of the time that was about teaching deaf students.26 Additionally, the alphabet published in Bonet’s book is the basis of the American manual alphabet.

Ponce de Leon and Student © Gallaudet University Archives.

Englishman Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–1665), who had visited King Philip IV in Spain as a member of Prince Charles’ entourage, was impressed by the appearance and manner of the handsome and gracious Luis de Velasco, then 13 years old. He also met Bonet. In 1644, Sir Digby wrote Treatise on the Nature of Bodies and mentioned his encounters with Bonet and Luis, the latter having received the title of Marquis de Fresno when he turned 18 years old in 1628. This book is said to have roused the idea that deaf people could be taught. One person whom it inspired was a physician, Dr. John Bulwer (1606–1656), who never taught deaf children but believed that one sense could take over the duties of another—the eye for the ear and the hand for the tongue.27 In 1644, Bulwer published Chirlogia, a book on fingerspelling; the handshapes described in the book are still used in British Sign Language. He wrote Philocopus in 1648, in which he advocated for the establishment of an academy for deaf people.

In England, William Holder, D.D. (1616–1698), and John Wallis, D.D. (1616–1703), were considered the first teachers of deaf people. Although they had intense interest in teaching deaf people, they could not put up with each other. In 1659, Admiral Popham and Lady Wharton hired Dr. Holder, a clergyman, to teach their deaf son; it can be again recalled that deaf children from elite society had more opportunities for education. Holder taught sounds, then combined them into syllables and finally whole words, using a two-handed manual alphabet. He described his teaching methods in a book, Elements of Speech with an Appendix Concerning People, Deaf & Dumb.

In the meantime, Dr. Wallis, also a clergyman and a tutor, agreed to teach a 25-year-old deaf man, Daniel Whalley, the son of the mayor of Northampton. After a year of instruction, Whalley could understand the Bible and read orally from it. A presentation of his newfound skills was made before the Royal Society and awed the members. However, the audience was not aware of the fact that Whalley lost his hearing at five years of age and therefore was postlingually deaf. Wallis read books on teaching the deaf by the Spaniard Bonet and taught reading, writing and speaking using gestures. He wrote Grammar of English for Foreigners with an Essay on Speech or the Formulation of Sounds.

Lady Wharton learned about Dr. Wallis’ presentation and success. She decided to remove her son from Dr. Holder’s tutelage after three years and place him with Dr. Wallis for instruction. Apparently this incident caused friction between the two educators for years.28

Another book on teaching the deaf was published in 1680, Didascalocophus (The Deaf and Dumb Man’s Tutor), by George Dalgarno. The Scot was the head of one of Oxford’s private grammar schools and was interested in the acquisition of languages. He published Ars Signorum (The Art of Signs) in 1661, which had nothing to do with sign language. After its publication, he became acquainted with the Holder-Wallis controversy and was captivated by the learning struggles and language acquisition of those born deaf. His background as a Latinist and a grammar school teacher offered him some insight in the process of learning and language acquisition.

Dalgarno may have been the first person to articulate the difficulty of blindness compared to deafness. He surmised that it was less difficult to be blind than to be deaf, and that was at least two hundred years before Helen Keller pronounced her thoughts on the same topic. Dalgarno concluded that, because of auditory input from birth, blind people had greater capacity for linguistic growth, with the ensuing talent of expression of thoughts and words. He theorized that a congenitally born-deaf child, without auditory input, did not have a similar natural vehicle of learning and thus was at a disadvantage from the beginning.

Interestingly, because of his involvement with the learning of deaf children, Dalgarno became an advocate of early childhood learning, especially for deaf people. He emphasized, in teaching deaf people, that it was necessary to be persistent “in order to lift the deaf child from his predicament of ignorance into understanding and communication.”29 The first of the six principles for teaching deaf children that he laid down was:

Here the first piece of diligence must be ... using the pen and fingers [fingerspelling] much.... Great care, therefore, must be taken, to keep your scholar close to the practice of writing; for, until he can not only write, but also got a quick hand, you must not think to make any considerable progress with him.30

Dalgarno created his version of the fingerspelling alphabet, said to be the first one developed especially for deaf people, as opposed to Bonet’s alphabet. It should be recalled that Bonet’s alphabet was presumably used by Benedictine monks who used fingers to circumvent their vows of silence. Dalgarno’s alphabet consisted of placing letters on different parts of the palm and pointing to the various spots to spell out words. The five vowels were located at the tip of each finger—the letter “a” at the tip of the thumb, “e” at the tip of the index finger, “i” at the tip of the middle finger, and so on. The placement of the vowels is still recognized and used in British countries as the two-handed alphabet.

By the end of the seventeenth century, successful teaching of deaf people was recorded in four European countries: Spain, England, France and Holland. The enthusiasm was noted by Kenneth Hodgson,31 who wrote about “...widespread recognition of the possibilities of teaching speech and speechreading. Miracles had become practical: something to be accepted as quite within the ordinary bounds of human achievement.”

Johann Amman (1669–1724) was an avid Amish physician who left Switzerland because of religious persecution and settled in the Netherlands. His teaching goals included making vowel sounds and consonant sounds, forming words and sentences, and lipreading as part of the language achievement. He described his methods in his book, The Talking Man, in the 1700s. He advocated oralism, and his methods of teaching deaf people influenced deaf people in Germany and France.

Henry Baker (1698–1774) opened the first school for the deaf in England. He taught his deaf niece using Wallis’ theories and used mirrors for speech practice, later writing a book, Motion of Fingers. Baker charged high fees for deaf children’s education and kept his teaching methods a secret until his death.

The first phase of the history of education of the deaf, as Eriksson32 noted, ran from the beginning of the sixteenth century until the late eighteenth century. Some characteristics of the teaching of deaf children during that period included:

• The education of deaf children was usually arranged by the family.

• Its purpose was to teach the deaf to communicate with other people orally or in writing.

• The students were rarely taught lipreading.

• The media of instruction were speech, writing, fingerspelling and signs.

• Because teachers jealously guarded the secrets of their trade, the art of deaf education was often veiled in mystery.

• Many teachers of deaf students thought their methods were of their own invention.

• Many teachers of the deaf were priests or physicians.

• Very little of what was written about deaf education at that time contained description of actual methods.

In Europe during the late 1700s, the Industrial Revolution took place, and many factories and steel mills were built. Many public schools opened for hearing children, while only a few private schools were opened for deaf children. People no longer believed that deaf people lacked intelligence. The first books in English about teaching deaf students were published. Some teachers were secretive about their methods, which slowed down the progress of education of deaf people.

This century is notable in the history of deaf education because:

• Formal, school-based education of deaf people (or the first public institution serving deaf individuals) began in England and France.

• For the first time, sign language was used consistently in a school; the school was founded by Abbé de l’Épée.

• For the first time, deaf students had a deaf teacher, Jean Massieu.

• The first known debate about sign language and speech began.33

Englishman Daniel Defoe is renowned for writing Robinson Crusoe, but he also wrote The Life and Adventure of Duncan Campbell. Campbell was a real-life person renowned throughout England for his psychic abilities, and he was deaf. Defoe wrote about how Campbell got his education via the British two-hand alphabet, and then Campbell learned speech.

Another Englishman, Henry Baker, had just completed his apprenticeship as a bookseller. The 22-year-old Baker was visiting relatives in Enfield when he learned about his deaf eight-year-old niece Jane Forester, who apparently had no previous learning. Baker came across Defoe’s book and found out about the work of Dr. Wallis. Baker became Jane’s teacher for nine years, and during that time, he became acquainted with Defoe’s daughter, Sophia. He and Sophia married in 1729 after he left his teaching position. Baker became a bookseller and kept his teaching procedures a secret.34

A mathematician by profession, Thomas Braidwood I surprised his colleagues in 1760 when he agreed to teach a 15-year-old deaf man, Robert Sherriff, how to write. Sherriff had lost his hearing at the age of three and appeared to be intelligent. After Sherriff learned to read and write, Braidwood decided to teach him speech. Braidwood was then motivated to teach other deaf students and announced the opening of a school in Edinburgh to serve children whose parents who could afford the tuition. The school grew, and in 1783 he moved the Braidwood Academy to Hackney, in the London area. His sister’s son, Joseph Watson, and his brother’s son, John Braidwood I, were trained to teach deaf students; they pledged to keep the methods within the family. When Thomas Braidwood I died in 1806, his widow and John directed the school program. After the death of both, John’s widow took over.

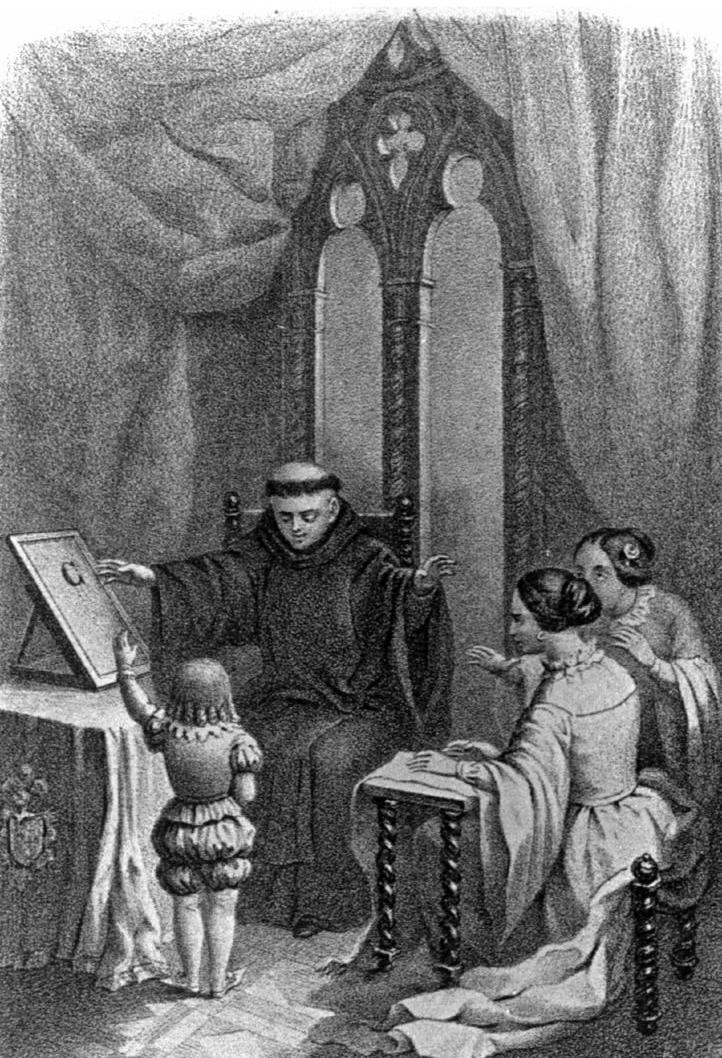

The London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, another school, was opened at Kent Road in 1792 to accept deaf children from poor families in London. It was the first public school for deaf children in Britain. Joseph Watson, the nephew of Braidwood I, left Hackney to become its principal and served for 37 years until his death in 1829. He was said to be an excellent teacher. His son, Thomas, succeeded him and held the job for 28 years.

The Deaf and Dumb Asylum, Kent Road. © Gallaudet University Archives.

In 1809, three years after Thomas Braidwood’s death—although he promised to keep the “Braidwood Method” a secret—Watson revealed the teaching method in a publication. The Braidwoods described their method as oral, but the students were allowed to use gestures and natural signs until they learned to talk. The Braidwoods also used the two-hand manual alphabet.35

In 1810, the Edinburgh Institute was founded in Scotland by the same group that started the Asylum at Kent Road. John Braidwood II, the son of John Braidwood I and a grand nephew of Thomas Braidwood I, became its principal. Two years later he was fired due to alcoholism. He later moved to the United States, where he continued his teaching career.

Germany developed a state school system for the deaf, presumed to be the earliest free public schools for deaf children. There were also state schools for the deaf in Austria, Sazony, and Prussia.36

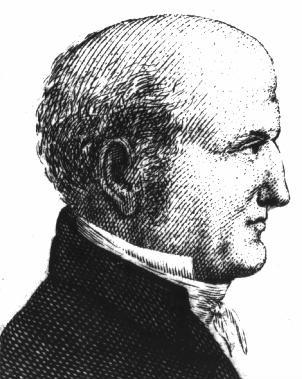

The most renowned German educator was Samuel Heinicke (1727–1790), who opened a school in Leipzig in 1778. He was influenced by Johann Amman (1669–1724), author of The Speaking Deaf. Amman, a Swiss, had moved to Holland because of religious persecution. He was a doctor who was unable to cure a deaf patient medically; instead he began to teach speech to the child. Amman wrote another book, A Dissertation on Speech, which was said to have profound influence on education of deaf children in Germany.

Samuel Heinicke © Gallaudet University Archives.

Heinicke rejected the use of signs, believing that sign language and the manual alphabet prevented the students from learning. He used speech as the only method of teaching and as a means of communication in the classroom. In 1778, he published Observations on the Deaf and Dumb. In advocating the pure oral method, he developed a set of eight principles of instruction, including:

• Clear thought is possible only by speech, and, therefore, the deaf ought to be taught to speak.

• Learning speech, which depends on hearing, is only possible by substituting another sense for hearing, and this can be no other than taste, which serves chiefly to fix the vowel sounds.

• Although the deaf can think in signs and pictures, this is confusing and indefinite, so that the ideas thus acquired are not enduring.

• The manual alphabet is useful, but, contrary to its ordinary use, it only serves to combine ideas.37

Heinicke’s career ended with his death in 1790, and his two living sons were not interested in his efforts. His widow and two sons-in-law tried to carry on his work. For a while, Charles de l’Épée’s work in France had influence upon teaching methods in Germany. However, with the latent influence of Heinicke’s teachings, the oral method experienced a revival in Germany during the nineteenth century.

In France, the earliest well-known teacher of the deaf was Jacob Rodriguez Pereire (1715–1790) of Spain. It is said that he became interested in teaching deaf people after tutoring his deaf sister before he moved to France. Another version is that he started working with deaf children after falling in love with a deaf girl. However, personal documents obtained from his son and grandchildren did not mention either girl. Students at Pereire’s school in Paris were sworn to secrecy about his teaching method, but “Pereire employed a one-handed alphabet for the teaching of speech, relied on a ‘natural’ approach to the development of language, developed auditory training procedures for individuals with residual hearing, and used special exercises involving sight and touch in sense training.”38 Pereire took his secrets to the grave in 1790.

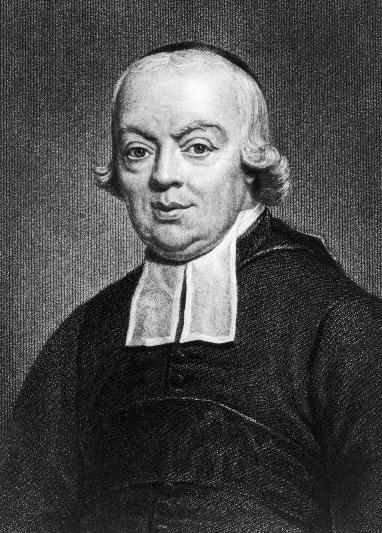

Meanwhile, the Catholic priest Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Épée (1712–1789) was visiting a family in an impoverished section of Paris when he happened to say hello to two girls. They were doing needlework in the living room and did not respond to him. Later he found out from their mother that the 15-year-old girls were deaf. Their father had passed away, and the girls were doing needlepoint to earn money for food. The mother was worried that her daughters did not know about God and religion. The priest had no previous knowledge of deaf people and teaching but noticed that the sisters used signs to talk with each other. He learned the signs and used them to teach the girls reading and writing.

Abbé de l’Épée © Gallaudet University Archives.

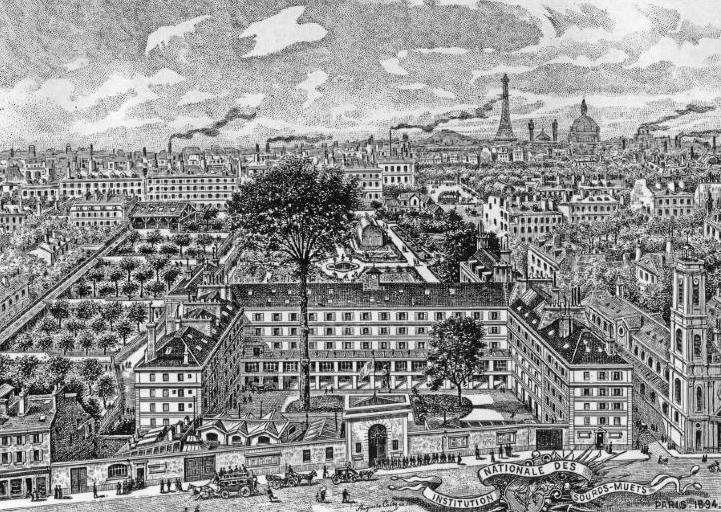

Initially, de l’Épée used his own methods, but eventually he was partially influenced by the writings of Amman and Bonet, the latter especially in regard to the one-hand alphabet. After finding several poor deaf children in Paris during the 1760s, de l’Épée used the small income from his family to establish a school for deaf children. The National Institute for Deaf-Mutes was the first free national school for the deaf in the world.

Royal Institute in Paris (note Eiffel Tower in background). © Gallaudet University Archives.

Compared to other educators, de l’Épée was not so secretive and was willing to share his teaching philosophy. He authored two books, Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb by Means of Methodical Signs in 1776 and True Manner of Instructing the Deaf and Dumb, Confirmed by Long Practice in 1784. The Abbé had considerable interest in speech development and suggested that teaching could be best done on an individual basis. He figured that by devoting ten minutes to each of his 60 students, it would take ten hours per day to complete the task.39 He was more concerned with other parts of teaching, especially reading and writing. De l’Épée was not opposed to the teaching of speech, but he considered it to be a slow, arduous process. He felt it was more important to attend to the overall education of his students.40

Contrary to popular belief, de l’Épée did not invent sign language. Rather, he copied the signs that his deaf students used and perhaps added some signs he learned from Cistercian monks who had taken vows of silence. He also created signs according to spoken French grammar. He called this sign system “signes methodiques,” or methodical signs; it was also known as the French method.41 De l’Épée wrote that the “methodical sign” was any sign used to instruct the deaf students because the signs were subject to rules.42 The signs, however, were not identical to those used by deaf people in the Parisian community. He was almost alone in advocating that deaf children be taught through signs instead of speech.

During his 29-year tenure with the school, de l’Épée trained many teachers. Among them was another priest, Abbé Roch-Ambroise Sicard (1742–1822), who opened a school for deaf students in Bordeaux in southwestern France and wrote a dictionary of signs.

Austrian Abbé Stark, also trained by de l’Épée, founded Austria’s first school for deaf students in Vienna in 1789. This establishment upset the ardent oralist Heinicke. De l’Épée invited his contemporaries—Heinicke and Pereire—to visit his school and observe the teaching methods. Both declined. Heinicke and de l’Épée then started a correspondence discussing teaching methods. In fact, some believe the infamous feuding that has marked deaf education through the ages began with the two men’s correspondence.

Heinicke objected to the introduction of language through either print or writing; it was his belief that in order for a pupil to think, the pupil first had to speak. De l’Épée countered with his conviction that children needed to learn how to read and write in order to function in society. He even brought the issues of deaf education and Heinicke’s philosophies before learned scholars at the Academy of Zurich. The February 2, 1783, response, “Decision of the Academy of Zurich, in an Assembly of Its Members on the Controversy Arisen Between the Teachers of the Deaf and Dumb,” was that de l’Épée’s approach was more effective and successful, and Heinicke was politely criticized for not trying to understand de l’Épée. Despite this affirmation of sign language, Heinicke’s work and influence spread throughout Germany and has continued to this day.43 The philosophical differences between de l’Épée and Heinicke were the start of the “two-hundred-year war” between supporters of sign language and supporters of oralism, explored in the next chapter.

The Paris school was primarily supported by gifts from individuals and grants from King Louis XVI. However, softhearted de l’Épée also used his family income to purchase food and clothing for his students. It is believed that this kindness led to his demise on December 23, 1789, at the age of 77. He had bought firewood to keep the children’s rooms warm but not for his own rooms. The extreme coldness deteriorated his health to the point of death.

De l’Épée is known as the first hearing educator interested in learning from deaf people themselves. He was an innovator in several ways. First, he united deaf people by directing his instruction toward a group, rather than isolated individuals. Second, he championed the idea that public education was to be available to all children, regardless of social status. Lastly, he emphasized the importance of using sign language for instruction.44 He nurtured an active deaf community in Paris where deaf people often visited each other and shared a common language. The first real deaf community is said to have been based in Paris, largely credited to de l’Épée.

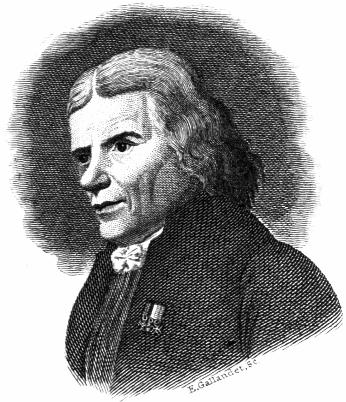

Sicard © Gallaudet University Archives

With de l’Épée’s passing, King Louis XVI appointed Abbé Sicard to become the director and principal of the National Institute for Deaf Mutes in 1790. Prior to this, Sicard had taught at Bordeaux. One of his pupils was Jean Massieu (1772–1847), who came from a family of five siblings—two brothers and three sisters—all deaf. Their parents were not deaf.

At the peak of the French Revolution in August 1792, Abbé Sicard was arrested, apparently for his Royalist opinions. He was placed in confinement along with members of royalty and nobility and some churchmen who proclaimed their allegiance to royalty. Deaf children banded together to demand the release of Sicard. Along came Jean Massieu, “the big fellow [who] stopped immediately below the high desk of the Tribunal ... reached up and placed a document on the desk of the Tribunal.”45 The secretary then read aloud a message:

August 26, 1782

Mr. President:

They have taken from the deaf and dumb their fosterer, their guardian, and their father. They have shut him up in prison as if he were a thief and a murderer. But he has not killed, he has not stolen. He is not a bad citizen. His whole time is spent in teaching us to love virtue and our country. He is good, just, and pure. We ask of you his liberty. Restore him to his children, for we are his children. He loves us as if he were our father. It is he who has taught us all we know. Without him we should be like beasts. Since he was taken away, we have been full of sorrow and distress. Return him to us and you will make us happy.46

The Tribunal quickly issued an order to release Sicard. However, in the midst of the confusion, he remained in prison. A week later, on Sunday, September 2, at three o’clock in the afternoon, he was pulled from his cell with 30 other prisoners to a courtyard where six carriages were waiting. A massacre allegedly started at the prison gate, and all the prisoners except Sicard were slain. Sicard had been rescued from the mob and hidden in the prison by a watchmaker who knew him. The next morning, over a thousand dead bodies were counted in the courtyard.

Two days later, Sicard escaped by hiding in a loft in his cell with two comrades who considered his life more important than theirs. Fortunately, all of them survived. It is said that Sicard had a few more escapes from death during the revolution and eventually was absolved of any guilt against the French Republic. He then returned to his duties as principal and director of the Institute.

Sicard was an outspoken person, and in 1797 he was banished to Guiana for supporting the Catholic Church and the Pope’s authority over the national government. He fled into hiding in the Paris suburbs. During his 28 months in hiding, he wrote two books: a general grammar book and a book on how he trained Massieu. The latter was the second book to explain how to educate deaf students.47 Massieu came to Sicard’s rescue again when he petitioned Napoleon Bonaparte to reinstate Sicard to his former job.

Sicard remained at the Institute for 32 years where “...emphasis on grammar was law at the National Institution, and training for speech discouraged as time-consuming and unprofitable for deaf people.”48 For his work, Sicard received honors from Tsar Alexander I of Russia, King Bernadotte of Sweden, and King Louis XVIII of France. In 1805, when Pope Pius VII visited Paris for Napoleon’s coronation, he made an official visit to Sicard and the National Institute.49

At the turn of the nineteenth century it was Sicard who, more than anyone else in the world, brought deaf people to the public’s attention. Had anything happened to Sicard during the turmoil, the direction of American education would likely be considerably different from what we know today.

Jean Massieu © Gallaudet University Archives

Massieu eventually became the first deaf teacher at the National Institute. Sicard had brought Massieu to Paris, where Massieu was appointed as a tutor. At the age of 25, Massieu taught Laurent Clerc. According to Clerc, Massieu was a character to the point of being eccentric. At times he would carry three or four watches, books, and small articles on his person and display them to everybody. His fascination for watches and his intimacy with the jewelers in Paris is believed to have been a factor in Sicard’s rescue from the deadly massacre and later from banishment during the French revolution.50

Massieu was much more of a thinker than a writer. He was said to have called on others to help him write business letters. However, according to Clerc, Massieu’s logic was highly convincing, and he was capable of the most abstract thinking. He has been credited with the following sayings:

“Gratitude is the memory of the heart.”

“Hope is the flower of happiness.”

“Hearing is the auricular sight.”

“A sense is an idea-carrier.”

“Eternity is a day without a yesterday or a tomorrow.”51

By the age of 45, Massieu was already famous, primarily as Sicard’s student. Upon Sicard’s death, Massieu, then 50, was the natural and sentimental choice to assume control of the school. His pupils, upon graduation, ended up all over the country. In fact, they directed schools for the deaf around the world—Lyon, Limoges, Besançon, Geneva, Cambray, Hartford and Mexico City. However, the administrative board did not choose Massieu to be the successor. His abstract thinking was not appreciated by the board members, who forced him to resign. He left everything—his home, his friends, his colleagues and pupils in Paris—and returned to his childhood home in Bordeaux.52

A year later, Massieu was hired by Abbé Pereire to be his assistant at a small school for the deaf in Rodez. Massieu fell in love with an 18-year-old hearing girl employed at the school and married her. When Abbé Pereire left to become the director of the National Institute, Massieu became the head of the Rodez school. Massieu, with his wife, a son and an infant daughter, later moved to Lille where they established the first school for the deaf in northern France, near the Belgian border.53 He died in August 1846 at the age of 75. His school died with him, and his widow and daughter set up a millinery business.54

Laurent Clerc (1785–1858), who had studied under de l’Épée and Sicard, was now teaching at the National Institute. Born in La Balme and the son of the town mayor, Clerc became deaf when, as a baby, he fell into the cooking fire. He wrote, “My mother ran over and scooped me up. She had always blamed the fall—probably herself—for my broken ears and mouth.”55 After numerous fruitless visits to doctors to restore his hearing, his parents sent Clerc to the National Institute. He was 12 years old and wrote of riding in a stagecoach with his uncle for five days from home in the southern part of France to the school—a distance of at least 360 miles.

Clerc, in recalling the day when Sicard came out of his exile and returned to the school, described the event:

We gathered in the assembly room to welcome him. Students, teachers, staff, and all the finest people of Paris were assembled.... So was the bishop and government officials, French nobility, and royalty from neighboring countries.... They crammed into the gallery above us, and the men in frilly collars and morning coats. Outside, carriages filled the courtyard.... Massieu was so excited that he couldn’t sit down. He walked back and forth, hands clasped behind his back, eyes aflame....56

Clerc was an excellent student and quickly rose to the position of student monitor in which he was responsible for the conduct of younger students. When Clerc was 20 in 1805, Pope Pius VII visited the National Institute. Clerc remembered, “My memory of the pope’s visit is flat, without excitement. He arrived the next day, flanked by a group of men, some of them in bright red clothes, all of them well-dressed and dignified.”57 On stage in the auditorium, the Pope handed over a copy of the book, Lives of the Popes, to Massieu, with Sicard and Clerc standing nearby. The pope asked Massieu to sign excerpts from the book, and in turn, Clerc translated them into perfectly written French.

Shortly after the Pope’s visit, and before graduation, Sicard offered Clerc the position of teaching assistant. Clerc was flabbergasted as he now had the chance to stay at the school—and get paid. Politics in France were returning to normal with Napoleon’s departure and the return of the deceased king’s younger brother, Louis XVIII, from exile. The school now had almost a hundred students; among them, one was from America, and one was from Russia. Although Massieu had a ten-year teaching seniority over Clerc, Clerc was eventually promoted to teaching the highest-level class. Massieu was not disappointed when he shook Clerc’s hand and congratulated him, remarking that the promotion would be good for their students.

After Napoleon’s defeat, the French army left Russia. Czar Alexander I, whose deaf son was Clerc’s student, asked for someone to start a school for deaf students in Russia. Sicard sent one of his teachers, Jean Baptist Jauffret. When learning of this, Clerc insisted on accompanying Jauffret. After several weeks, he was tersely told by Sicard that he could not go as Russia was poor and had money for only one teacher.

Almost a decade had passed since Clerc started teaching. Napoleon had escaped from prison and his army was marching toward Paris. King Louis was a close friend of Sicard and often attended the school’s performances. King Louis also met personally with Massieu and Clerc when visiting. Since Sicard, Massieu, and Clerc were threatened by Napoleon’s march toward the city, they decided to leave the country for a while.58 Unbeknownst to Clerc at that time, he was embarking on a lifelong new career.