People are the backbone of history. The events as pointed out in the annals of deaf history are the results of the contributions of dedicated people who shaped the world and the American deaf community. This chapter presents the numerous individuals who have left, and continue to leave, their legacies in molding not only the deaf world but also the non-deaf world.

Journey into the DEAF-WORLD1 identified two groups of great leaders who have played a disproportionately large role in leading in the Deaf community. The first group consists of intercultural leaders—leaders who were born hearing to hearing parents and became Deaf after learning to speak English and after having extensive contact with the larger and hearing society, benefiting the Deaf community. The second group consists of culturally centered (or grassroots) Deaf leaders—leaders who were born to Deaf parents and whose cultural knowledge of Deaf culture and fluency in ASL are particularly valuable. They are predominantly found in positions within education, Deaf organizations, or athletic organizations.

The authors wish to avoid further categorizing and further stereotyping between the two groups. However, it should be pointed out that there are children who are born deaf to hearing parents or become prelingually deaf and do not fit into either group. Furthermore, there are instances of children being born hearing to deaf parents but becoming deaf after acquiring language (postlingually deaf).

At any rate, it is interesting to note that the 22 NAD presidents, from NAD’s inception in 1880 through 1978, were postlingually deaf. Since then, all of the nine presidents—with the exception of Larry Newman, who lost his hearing at the age of five—were born to deaf parents.

The authors believe there are several main reasons for the cultural shift. First, a great majority of deaf individuals in early days lost their hearing due to a number of factors, mostly through serious illnesses such as measles, spinal meningitis, scarlet fever, and whooping cough. Those deafened individuals heard spoken language and were fluent in spoken English before losing their hearing. Often they retained the use of speech even after becoming deaf. In fact, many of them were partially deaf. They were called hard of hearing, or “semi-mutes,” as some old-timers would call them.

With the disappearance of childhood diseases through immunization, there are fewer occurrences of children who become deaf at later ages. Instead, there is a higher occurrence of children who are born deaf, mostly due to hereditary causes even within hearing families. As a result, there are more deaf children who do not hear spoken language even in infancy. Since they become deaf before learning language, they are prelingually deaf.

The fact that several NAD presidents in more recent years have come from deaf families is believed to be an outcome of the increased assertiveness of deaf people through recent generations. After the 1960s when deaf people became more involved in their own causes, they gained self-confidence and possessed a stronger cultural identity. Deaf parents were then able to share experiences and lessons with their deaf children. Using their parents as role models, the younger generations then became more proactive in the fostering their peers’ interests.

For deaf people, social gatherings and publications were the main sources of contact with their peers. Many deaf-school graduates maintained updated connections with their alma maters through school publications. The “Little Paper Family” was a vital network where schools exchanged publications with other schools. The publications usually contained a section or a page devoted to alumni doings on social, family and other affairs and were read by students and faculty.

There were several national publications. The larger ones—most of which do not exist now—were Silent Worker, Cavalier, The Frat (for National Fraternal Society of the Deaf members), and Silent News. Current publications are Deaf Life, New Horizons (for Deaf Seniors of America members), and SIGNews. Some state associations for deaf people also print newsletters.

In the present age of convenient Internet access, news sharing among deaf people has not only proliferated geometrically but has also become more updated. When a noteworthy deaf person dies, the news is known all over the globe within a day. In 1996, the late Phil Moos of New Jersey began distributing USA-L News, an online mailing list of announcements and articles about deaf-related events or individuals within the deaf community. The venture has been taken over by DeafTimes, which sends out DeafTimes News and other state-level mailings. Two editions of DeafDigest, compiled by Barry Strassler, are sent out weekly. He also distributes DeafDigest Sports.

The 2006 Gallaudet University protest is an excellent example of how news was instantly made available to interested parties, not only across the country but also all over the world. Even though the deaf population may be fragmented, deaf people immediately got together to show their endorsement of the protest. Over 70 tent cities were held all over America within two weeks of the protest, mostly by Gallaudet alumni. This support was further reinforced by national, state, and local organizations that offered monetary contributions to “Tent City” at Gallaudet for food and other necessities. This was accomplished mostly through a great number of blogs and vlogs. Although some people disagreed with the protest, Internet postings were overwhelmingly in support of the protest.

There is a life-size oil painting of Frederick Schreiber (1922–1979) hanging at the NAD headquarters. The unique advocate was a giant among his contemporaries.

Schreiber lost his hearing at the age of six years in New York. He attended the New York School for the Deaf and then graduated from Gallaudet College (now University) at an early age. He taught for a while in Texas before relocating to Washington, D.C. While employed at a full-time night job as a printer at the Washington Evening Star, followed by a position as a compositor in the United States Government Printing Office, he labored feverishly, pushing legislation for more deaf rights. In 1966, he became the executive director of the newly established NAD home office. Confident of the NAD’s future, he mortgaged his home, and with additional money from colleague Albert Pimentel, he bought an office building in Silver Spring, Maryland, in the early 1970s.

Schreiber is remembered for his fights and advocacy for deaf people’s rights. Garretson2 remembers him this way: “Brilliant, articulate, aggressive, and yet sensitive and blessed with a gift of humor, warmth, and peopleness, this human dynamo began early to gain those experiences which provided meaning and substance to his eventual national and international contributions.” Even after his unexpected death in 1979 at the age of 57 after working for NAD for 13 years, Schreiber’s legacy is forever honored and cherished. Among his well-known sayings are:

“What is between the ears is more important than what is in the ears.”

“There are only two kinds of people: Those that can’t hear and those that won’t listen.”

“Deaf people can do anything except hear.”

“As far as deaf people are concerned, our civil rights are violated daily.”

Andrew Foster, deafened at the age of 11 and educated at the Alabama School for the Deaf, was the first known African American to graduate from Gallaudet College and the same from Eastern Michigan University. After receiving a degree from Christian Mission College in Washington, he became a minister. He went to Africa and helped establish over 30 schools for deaf children, most of them affiliated with churches in Western African countries including Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Chad, Ghana, Kenya, and Zaire. He died in a plane crash in 1987.

I. King Jordan, Ph.D., the eighth president of Gallaudet University, lost his hearing in a motorcycle accident as a young adult while serving with the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C. He attended Gallaudet College as an undergraduate. He then earned both a master’s degree and a doctoral degree in psychology from the University of Tennessee. In 1973, he joined the Gallaudet faculty in the psychology department and later served as the dean of the College of Arts and Science. His family moved to House One on the Gallaudet University campus after his inauguration as the first Deaf president of Gallaudet University in March 1988. He retired in December 2006.

Robert Davila, Ph.D., of Hispanic descent, was a vigorous, tireless educator and administrator. He has held numerous positions within the education field, including teaching in the graduate school at Gallaudet University before being promoted to university vice president. He was later selected by President George H.W. Bush to become the Assistant Secretary for Special Education and Rehabilitation Services in the U.S. Department of Education, the highest government position ever held by a Deaf person. He was also the headmaster at the New York School for the Deaf (Fanwood) and then the vice president for the National Technical Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology before his retirement in 2004. He is also the first person to have served as president for all three deaf education professional organizations: the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf, the Conference of Educational Administrators Serving the Deaf, and the Council on Education of the Deaf. In January 2007, he became the ninth president of Gallaudet University. He retired in January 2010.

Marilyn J. Smith is the founder and executive director of the non-profit Abused Deaf Women’s Advocacy Services (ADWAS). Founded in 1986, ADWAS was the only program of its kind in the nation until 1999, when the agency received a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice; today, the program has been replicated in 15 cities. In March 2005, ground was broken for “A Place of Our Own.” The 19-unit affordable housing complex opened in July 2006 and serves deaf and deaf-blind victims of domestic violence and sexual assault. She retired in January 2011.

In 1975, South Dakota native Ben Soukup founded Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD) as a part of the South Dakota Association of the Deaf. The original purpose of CSD was to secure and schedule sign language interpreters and provide TTY repair service. Later, the agency, based in Sioux Falls, became an agent for the statewide relay service.

The organization expanded when CSD signed with several other states to run their relay services. Soukup’s leadership and persistence paid off with services in several states, employing over a thousand workers and supporting more than 20 satellite offices. These programs reach deaf and hard of hearing consumers from cradle to grave through a variety of services and functions. CSD also publishes the monthly SIGNews newspaper. In late 2010, CSD was awarded a $14.9 million federal grant to create high-speed Internet access for low-income Deaf and hard of hearing people. Through Project Endeavor, the individuals will receive laptop computers with mobile broadband cards and be eligible for a year of high-speed wireless Internet access.

Ruth Seeger, a well-known teacher and athlete at Texas School for the Deaf, not only started the girls’ athletic program at the school but also coached many of her protégés to participate in world competitions. As a young athlete, Seeger won several gold medals for the U.S. track and field team at the Deaflympics. Later on, she coached the U.S. women’s track and field teams for two decades. After retiring from the school, she decided to return to her true love, which was to compete again. The fitness buff competed in five field events—javelin, shot put, discus, long jump and high jump. From 1991 to 2005, Seeger garnered a total of 304 medals, including at least 280 gold medals. She also holds a national record in javelin, hurling it for 50 feet and 8 inches.3 As a young lady, Seeger admired Babe Didrikson Zaharias, who was named Top Woman Athlete of the Century by the Associated Press in 1999. As a result, Seeger is often referred to as the Deaf Babe Zaharias.

Seeger has the unique distinction of being inducted into at least ten halls of fame as an athlete, coach and sports leader, including being the first deaf female to be inducted into the USA Deaf Sports Federation Hall of Fame in recognition of her 20 years as track coach. In 1988, Texas Governor William P. Clements inducted Seeger into the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame as athletic coach, and in 1999, Seeger was honored as the newest member of the Texas Senior Games Hall of Fame. TSD named its gymnasium after her, a testimony to Seeger’s love for her “girls,” athletics, sports equality, and healthy living. A highly unusual award for the octogenarian was made when, in 2006, she was awarded the Austin Female Amateur Athlete of the Year.

Robert and Michelle Smithdas, both deaf-blind, are leading remarkable lives. Robert, or Bob as he is known, lost his hearing and sight at the age of four from illness. In 1950, he earned a bachelor’s degree from St. John’s University and became the first known deaf-blind man to finish college. In his graduate studies, he majored in vocational guidance and rehabilitation of the handicapped at New York University and in 1953 was the first deaf-blind person to earn a master’s degree. He began his career at Industrial Home for the Blind, now known as the Helen Keller School for the Blind, in New York as director of services. The Helen Keller National Center for Deaf-Blind Youths and Adults (HKNC) was established in Long Island, New York, after Bob helped to obtain federal funding in 1967. He was affiliated with HKNC as its director of community education until his retirement in December 2008. Bob has been awarded four honorary doctorates from colleges and universities and was named “Handicapped American of the Year” in 1965 by the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities.

Bob married Michelle Craig in 1975. Originally from California, she was blinded in a snowmobile accident during her senior year at Gallaudet University. Later, she earned her master’s degree in the education of blind and visually impaired at Columbia University. She entered the training program at HKNC in 1972 and subsequently became an instructor.

Barbara Walters, a well-known ABC TV commentator, interviewed Bob on the Today Show in the 1970s, and in 1998 interviewed the couple for 20/20. Walters spoke at Bob’s retirement luncheon and stated that, in her 30 years of interviews with notables, Bob was the most memorable.

Additional deaf people with noteworthy contributions include:

• Thomas Edison (1847–1931), deafened at the age of 14, brightened the world with his invention of a light bulb and obtained a total of 1,097 U.S. patents under his name.

• John Gregg (1867–1948) was the brainchild of shorthand writing.

• Juliette Gordon Low (1860–1927), deafened at the age of 20, founded the Girl Scouts organization in 1912.

• Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770–1827), deafened at the age of 30, was an internationally renowned musician.

• Nanette Fabray (1920–), although possessing hearing loss, was well-known as a comedienne, singer, dancer, and actress. She was one of the earlier advocates for the rights of deaf and hard of hearing people.

The list could go on and on. There are deaf or hard of hearing firefighters, morticians, lawyers, dentists, doctors, chemists, inventors, artists, sculptors, writers, architects, poets, newspaper editors, clergy, actors, and teachers—to mention just a few!

Some notable Deaf “firsts” include interesting individuals.

Betty Lou Beets—First Deaf person to be executed. She was sentenced to die by lethal injection in 2000 for the murder of her fifth husband. Home state: Texas

Thomas Coughlin—First Deaf Catholic man to become a priest, in the 1970s. Home state: New York.

Eugene Hairston—First Black Deaf professional middleweight boxer, who won 60 bouts and lost one as an amateur in New York. He turned professional in 1947 and won a total of 45 matches (24 by knockouts) and lost only 13 times with five draws in the 1950s. He was known as The Deaf Wonder and was ranked as a top middleweight contender for two consecutive years. Home state: New York.

William Hoy—First Deaf Major League baseball player, for the Cincinnati Reds and the Washington Senators (1886–1901). Home state: Ohio. Other players include Luther Taylor, Richard Sipek and Curtis Pride (who was the first Black Deaf major league baseball player).

Christy Smith—First Deaf woman to appear on the TV series, Survivor: The Amazon, in 2000. Home State: Colorado.

Erastus Smith—First Deaf soldier to spy against Mexico in 1821. Home state: Texas.

Luke Adams—First Deaf person to participate in Amazing Race, a TV series. He and his mother, Margie Adams, competed with ten other couples and placed third.

Nellie Willhite—First female Deaf pilot, she flew in many air shows and races in the late 1920s. Home state: South Dakota.

Boyce Williams—First Deaf person to serve in the U.S. Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, in 1945. Home state: Wisconsin.

Heather Whitestone—First Deaf female to be crowned Miss America, in 1995. Home state: Alabama.

Alice Cogswell’s impressive composition in the first chapter is an example of the work of many excellent deaf writers throughout the years. Some of them owned newspapers and wrote their own news and editorials. Some of them were nationally acclaimed poets. Some of them earn their living as technical writers for the government or industry. Most of the Little Paper Family publications, described earlier in this chapter, were composed and edited by deaf wordsmiths, who often taught English full-time in the classrooms.

Several persons who are known for making fun of themselves as deaf persons through words, or write extensively about deaf people are listed below.

• Steve Baldwin is known for his well-researched and documented study of Pictures in the Air: The Story of the National Theatre of the Deaf. He also authored countless cultural, historical, and professional articles. He also writes scripts for television, movie and stage; among them are T. H. Gallaudet and Monsieur Clerc: Coming to Terms and Deaf Smith: The Great Texan Scout.

• Mark Drolsbaugh grew up with progressive hearing loss and resided four blocks from Pennsylvania School for the Deaf’s (PSD) Mt. Airy campus. He attended hearing schools and had his first intensive exposure to Deaf culture when attending Gallaudet University. With a master’s degree, he returned to Philadelphia where he has become a school counselor at PSD. He dabbled in writing, with articles for several deaf national publications and other journals. Since he could not “shut up” as he described himself, he has ventured into books and has published Deaf Again and On the Fence: The Hidden World of the Hard of Hearing. Drolsbaugh, using the best of his humor and insight, gave flavor to his compilation of thought-provoking articles in Anything But Silent. His latest work is now in progress—The One Hundred Dollar Hearing Aid Battery—a children’s book based on a true story.

• Jack Gannon has written extensively about deaf heritage for almost 30 years. In Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America, he presented a comprehensive account of deaf legacy throughout the two centuries since the founding of American School for the Deaf in Hartford. He has also authored The Week the World Heard Gallaudet and was one of the designers of the History Through Deaf Eyes exhibit and book. He is nearing completion of his latest venture, which records the history of the World Federation of the Deaf and its national organizations.

• Comedian Ken Glickman created many humorous “deaf” definitions, published in Deafinitions and More Deafinitions. An example deafinition is of the word “lens-propelment,” which is described as the sudden act of hurling one’s glasses accidentally while signing.

• Roy K. Holcomb (1923–1998) authored several books in relation to Deaf culture, through humorous anecdotes. Misdeeds, such as using a vacuum cleaner and later realizing that it was not plugged in to an electric outlet, are described in books like Hazards of Deafness and Silence is Golden ... Sometimes. His last book, Deaf Culture ... Our Way, was written with his two sons Samuel and Thomas.

• Raymond Luczak’s first novel, Men with Their Hands, won first place in the Project: QueerLit 2006 contest. Since graduating from Gallaudet University in 1988, he has written seven novels and 13 stage plays, of which one—In Love and Lust We Trust—was performed in London.

• Damara Goff Paris was the owner of a publishing company, Paris Publications. A descendant of a Cherokee/Blackfoot family, she co-edited, with the late Sharon Kay Woods, Step into the Circle: The Heartbeat of American Indian, Alaska Native, and First Nations Deaf Communities. Her company published titles such as Deaf Culture Behind Bars and Deaf Esprit: Inspiration, Humor and Wisdom from the Deaf Community.

• Maxwell Schneider published Do You Hear Me, in which she demonstrated the humorous ways of hard of hearing people. A sample snippet: “I know a man who is hard of hearing who has the grip of a trapeze artist. Naturally, he hangs on to your every word!”

• Bernice Singleton collected breast cancer stories from 50 women and one man from all over the United States. The book, Signs of Courage: Deaf Survivors of Breast Cancer, contains real-life experiences, including the victims’ prognosis and treatment, Most of them are still living.

To give a general picture of what deaf people in the nation can do in various types of business that they founded and operated:

• David Birnbaum, of Birnbaum Interpreting Services in Silver Spring, Maryland, and Eric and Moon Feris, are owners of two of four deaf-owned interpreting/videophone firms. Being deaf, they have a unique perspective in the field of interpreting as compared to the many firms owned by hearing persons.

• Skiqwaqui, a nine-hole golf course in Morganton, North Carolina, was designed and is owned by Charles Crowe.

• Joe Dannis founded DawnSignPress in San Diego, with a focus on ASL and Deaf culture publications. The firm, established over 25 years ago, is well known for its Signing Naturally ASL curriculum. In 1997, Dannis received the Small Businessperson of the Year award for the state of California.

• Bob Harris, of Minnesota-based Harris Communications since 1982, runs an Internet and mail order business that sells various hearing loss equipment, novelties and books/DVDs.

• James Macfadden owned Macfadden and Associates, Inc., a computer-consulting firm that earned $12 million a year in revenue through federal government contracts in Washington, D.C. In 2007, he sold the company to his 80 employees through its Employee Stock Ownership Plan Trust Fund. He is now a freelance entrepreneur and serves on the Gallaudet University board of trustees.

• Technical Computer Services (TCS) designs and repairs computer systems and provides assistive technology in federal government, in Maryland. Established in 1982, it is owned by Myrna Orleck-Aiello, the president and chief executive officer, and Phil Aiello, the chief technical officer.

• Louis Schwarz’s Schwarz Financial Services provides financial planning and tax preparation services. It was founded in 1983 and is operated out of Maryland. An avid collector, Louis Schwarz has a unique hobby: the collection of Deaf Americans’ business cards. His binders of over 700 business cards are found in a sitting room area in his office for clients or visitors to browse through.

• Trudy Suggs, a prolific writer, established T.S. Writing Services in 2003 and provides writing, editing and design services in ASL and English. Her firm works with individuals and businesses all over the world. Working from home in a log house surrounded by open countryside outside Faribault, Minnesota, she and her staff conduct business predominantly via the Internet and video technology.

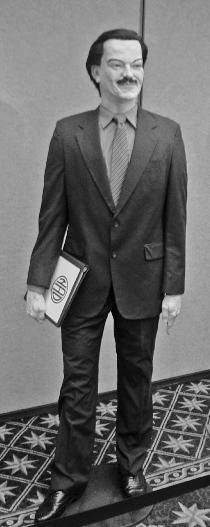

One of the top attractions at the 2005 Deaf Seniors Conference in San Francisco was a room where conference participants came face-to-face with famous deaf individuals of bygone decades. They exclaimed at William Hoy’s demure 5'5", attired in his Washington baseball uniform as the first deaf player in the major leagues. Other notable figures included Girl Scouts of America founder Juliette Gordon Low, American School for the Deaf founder Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, and the first Deaf teacher in America, Laurent Clerc. The eight life-size, three-dimensional wax figures on display were so realistic that visitors were tempted to shake hands or chat with them in ASL. A look-alike figure of Fred Schreiber with his ever-present enticing smile and his assertion, “Ears are not important. It’s what’s between them that counts,” was unveiled at the conference.

Three figures in the traveling Deaf Heritage Wax Collection. William E. “Dummy” Hoy, 1862–1961, “Deaf Major League Ballplayer.” Hoy was a fixture in the Major Leagues for 14 years (1888–1902) with five teams. He had a lifetime batting average of .288 with a total of 2,054 hits and 1,004 walks in 1,798 games. The five-foot-five speedster ranks 17th among the all-time leaders in stolen bases with 607. He is credited with inventing hand signals for “strike” and “ball,” which are still being used today.

Juliette Gordon Low, 1860–1927, “Founder, Girl Scouts of the USA.” Low, deafened at the age of 26, founded two Girl Scout troops in her hometown, Savannah, and it was the beginning of the Girl Scouts movement in the USA. She was also a skilled artist, painter, sculptor, and writer. She was buried in her Girl Scout uniform.

Frederick C. Schreiber, 1922–1979, “Deaf Rights Advocate/Activist.” Schreiber became deaf at the age of six and a half from spinal meningitis and entered Gallaudet College at the age of 15. His early career included teaching, tutoring, counseling and work as a printer. He entered community service when he became the first executive secretary of the National Association of the Deaf in 1966, and he expanded NAD to a million-dollar association with 40 employees. He was well known all over the world for his advocacy efforts for deaf people. Photographs by the author.

Don Baer, a native Californian and the founder of the Deaf Heritage Wax Collection, was present to share his apprenticeship experience at Hollywood Wax Museum and his desire to preserve Deaf heritage and culture by creating a collection of at least a hundred wax figures representing individuals who have influenced the lives of the Deaf throughout the years.4 Don has continued to add to his collection; the latest is of Bernard Bragg performing mime. During the last ten years DEAFWAX, a non-profit organization, exhibited in at least 25 local and national events.

In reviewing the contributions of deaf people in America, there are so many who deserve to be mentioned. Space does not permit discussing each notable person. Instead, a brief outline discusses the contribution each Deaf person has made.

Hillis Arnold, North Dakota (1906–1988) Many of his sculptures are in St. Louis and Midwest states, and his work was exhibited at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. In 1938, he was appointed to a private junior college for women (now known as Lewis and Clark Community College in Godfrey, Illinois) as professor of sculpture and ceramics. Upon his retirement from the college after 34 years, he was awarded the rank of Professor Emeritus of Sculpture.

John Brewster, Maine (1766–1854) Renowned as a portrait painter in New England, Brewster’s works continues to be exhibited today. At the age of 51, he interrupted his work to attend American Asylum for the Deaf as one of its first pupils and stayed there for three years. Early in 2007, his two portraits Daniel Coffin and Elizabeth Stone Coffin were auctioned to an unidentified buyer for $801,600.5

Morris Broderson, California (1928–) Broderson’s oil paintings, watercolors, pastels and lithographs are part of permanent collections at Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. His works were exhibited at the M. H. De Young Museum in San Francisco, the University of Arizona in Tucson, and several others, including some universities.

John Carlin, Pennsylvania (1813–1891) As an artist, Carlin painted portraits of personalities such as William Seward, Horace Greeley, and Jefferson Davis. He was an inexhaustible writer; his articles on architecture, geology, and ecology were published in leading newspapers. He was the first deaf poet whose work was praised by William Cullen Bryant. A dormitory building at Gallaudet University is named after him.

George Catlin (1796–1872) Catlin spent eight years traveling to document in painting every Native American tribe in America. He was the first artist to travel to the west with the purpose of learning more about Native Americans. Over 500 of his paintings and sketches recorded the “manners and customs” of American Indians, and he was also a writer and documented how the government treated the Native Americans. His paintings were exhibited in one of the Smithsonian museums recently.

Louis Frisino, Maryland (1934–) Often called Deaf John James Audubon, Frisino is well known for his realistic detailed paintings of animals. His work has won several Duck Stamp contests and Trout Stamp contests. His dog and waterfowl paintings have also earned several federal and state awards.

Kathleen Giddens, Florida (1949–) Giddens’ surrealism and humor art in oils, acrylics, colored pencils and mixed media have been exhibited all over the country for the past 40 years. Her creations have won many awards.

William B. Sparks, North Carolina (1937–) As an oil portrait painter, Sparks is known for capturing his subject’s personality in creating lifelike and almost photographic reproductions. His works have been exhibited in the Eastern United States, Brazil and Mexico. He painted formal portraits for the last four Gallaudet University presidents.

Douglas Tilden, California (1860–1935) Several of Tilden’s sculptures adorn the streets of San Francisco; the best-known ones are the Mechanics and the California Volunteers. The Mechanics, completed before 1900, survived the infamous San Francisco earthquake in 1906 and is still standing. He is often called the “Michelangelo of the American West.”

Sculpture: Mechanics by Douglas Tilden, 1901, located at Market, Battery, and Bush streets, San Francisco.

Sculpture: California Volunteers by Douglas Tilden, 1906, located at Market and Dolores streets, San Francisco. Photographs by the author.

Cadwallader Washburn, Minnesota (1866–1965) An adventurer, Washburn interviewed revolutionary foreign leaders and taught cannibals sign language. He was well known for developing dry point etchings, and he created over 1,000 etchings, in addition to oil paintings and watercolors. Most of his collections are now at the Library of Congress and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The art building on the Gallaudet campus is named for him.

Those interested in art might like to read Debbie Sonnenstrahl’s outstanding book, Deaf Artists in America. It contains profiles of over 60 artists’ lives and selections of their work with vivid descriptions. Jack Gannon’s book Deaf Heritage also contains an excellent collection of artists and other notable deaf individuals in American history.

Shelley Beattie, Oregon and California (1967–2008) In 1990, Shelley won the National Physique Committee USA title as a body builder. She participated in the American Gladiators television show for three seasons as “Siren.”

Lou Ferringo, New York and California (1951–) Ferringo is most recognized for his role as the green giant in The Incredible Hulk television series between 1976 and 1981. At the age of 20, he was the youngest ever to win the Mr. Universe title—by a unanimous decision over 90 experienced contestants. He later lost the Mr. Olympia world title to Arnold Schwarzenegger.

LeRoy Colombo, Texas (1905–1974) As a lifeguard for 40 years for the city of Galveston, he saved the lives of 907 persons. A strong swimmer, he won many long-distance races.

Marsha Wetzel, New York (1963–) In 2002, Marsha Wetzel secured a position as a referee in the NCAA Division I men’s basketball, becoming the first Deaf female to do so. She had been refereeing for more than a decade in high school and Division III basketball before going over to work in the Atlantic 10 and Patriot League conferences; she still officiates at Division III and high school games. Wetzel is currently a teacher at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf.

Rhulin Thomas, Missouri and Maryland (1910–1999) In 1947, Thomas was the first deaf aviator to fly across the nation—from the Atlantic Coast to the Pacific Ocean. It took him 12 days and, because of his deafness, he flew without any radio equipment.

Olof Hanson, Minnesota (1862–1933) Hanson was one of the first Deaf Americans to become an architect. He designed a total of 48 homes, 28 buildings, 18 schools and institutional buildings, churches and other structures. The United States Court House in Juneau, Alaska, is one of his famous works. State Route 299 circles the campus of Minnesota State Academy of the Deaf and is named Olof Hanson Drive.

Thomas Scott Marr, Tennessee (1866–1935) Marr’s architecture firm designed many buildings in Nashville, among them the post office building, three modern luxury hotels, large apartment buildings, and two theaters. His last project was the State Supreme Court building. He was known as the “Dean of Nashville’s Architects.”

Thomas J. Posedly, Arizona (ca. 1940–) In 2007, Posedly was awarded the Arizona Architect’s Medal, the highest honor given by the Arizona American Institute of Architects. He is one of five known professional deaf architects in the United States and is licensed in all 50 states. In his 35-year career, he has been involved with over 100 projects including commercial buildings, shopping centers, educational facilities, and churches.

Frank G. Bowe, New York (1947–2007) After receiving a doctorate in educational psychology from New York University, Bowe became a disability-rights advocate. He was involved in many activities and wrote over 25 books on disability rights and other topics. He was a professor at Hofstra University’s School of Education from 1989 until his death in 2007.

Heather Whitestone, Alabama and Georgia (1973–) Best known as the first deaf lady to be crowned Miss America in 1995, Whitestone had a cochlear implant surgery in 2002. Married to a politician, with whom she had two children, she tours as a motivational speaker.

France Woods, Ohio (1907–2000) Married to a hearing man, Woods was one of the professional dancers known as “Frances Woods and Billy Bray.” They performed all over the nation and in Europe for over 55 years. Ripley’s museum contains a wax replica of the couple as “The Wonder Dancers.”

John R. Gregg, Illinois (1866–1948) Gregg invented the Gregg Shorthand system and started the Gregg School, which became a business school. At the age of 19 he was considered a world authority on shorthand writing.

Anson R. Spear, Minnesota (1860–1917) Spear invented and patented a merchandise mailing envelope and secured two patents. He established the Spear Safety Envelope Company, which prospered for many years and employed many deaf workers.

Robert Carr Wall, Pennsylvania (1858–1939) In 1900, Wall built the first gas-powered automobile in Philadelphia and sold it for $1,800. He also developed the first bicycle that had both wheels of the same size. His firm made rattle-proof windshields for the Packard automobile company.

Michael A. Chatoff, New York (1946–) While in law school during the late 1960s, Chatoff became deaf. He graduated from the New York University School of Law with a Master of Laws degree. He is known to be the first deaf lawyer to argue a case before the Supreme Court, and it was the first time that the Court permitted the use of technology (real-time captioning) in its hallowed halls of justice.

Lowell Myers, Chicago (1930–2005) A certified public accountant, Myers finished law school in 1956 ranking second in his class although he did not have an interpreter. He handled both deaf and hearing clients. He successfully defended a black young man who was accused of murder (this case was eventually the topic of a book and made into a 1979 television movie starring LeVar Burton). Myers represented at least a thousand deaf persons in court. In 1979, he was honored with the Distinguished Alumnus Award by the John Marshall Law School.

Bonnie Poitras Tucker, Massachusetts and Arizona (1939–) After majoring in journalism, Tucker married a hearing man. After 17 years, he divorced her because she was deaf. She finished law school at University of Colorado Law School. After several years of private practice, she became a tenured law professor at Arizona State University College of Law.

William W. Beadell, New Jersey (1865–1931) Beadell was a weekly newspaper publisher in Illinois and later owned a run-down daily newspaper in Arlington, New Jersey. The Observer later became successful, and Beadell was credited with developing the “Want Ad” page or classified ads.

Edmund Booth, Massachusetts and Iowa (1810–1905) A pupil of Laurent Clerc at American School, Booth taught there for nine years. He moved to Iowa where he helped found the Iowa School for the Deaf. Later he became a gold prospector during the Gold Rush of 1849. Returning to Iowa in 1854, he bought a weekly newspaper and became its editor. He helped found the National Association of the Deaf. In 1880 he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree by Gallaudet University.

Laura Redden Searing, Missouri (1840–1923) A journalist and poet who was recognized by her peers in literary world, Searing was a Civil War correspondent for the St. Louis Republican and wrote for two New York newspapers. She also wrote about people, places, politics and books under the pen name of Howard Glyndon.

David Pierce, Texas (1965–) A 1988 graduate of Rochester Institute of Technology, Pierce is the owner and CEO of Davideo Productions, a motion picture film and broadcast television production in Seguin, Texas. He is also the inventor of an editing technique for cutting video to audio by deaf editors, known as the “Pierce Method for Deaf Editors.”

Henry Kisor, Illinois (1940–) A retired book editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, he is known for authoring What’s That Pig Outdoors?, a humorous account of his life as a deaf man growing up in a non-deaf world. He lost his hearing at age three and a half. After earning a master’s degree from Northwestern University, he began his writing career. Instead of relying on lipreading skills, he audiotaped his interviews and had his wife transcribe the tapes. Retired in 2006 after five years with the old Chicago Daily News and 28 years with Sun-Times, he has written two other nonfiction books and three mystery novels.

Donald L. Ballantyne, China and New York (1922–2006) As the director of the Microsurgery Training Program at New York University Medical Center, he was a pioneer in the field and trained surgeons in the United States and Europe. He co-authored over 75 journal articles and two books on the technique. After his retirement in 1990, NYU designated him Professor Emeritus of Surgery.

Frank Peter Hochman, New York and California (1935–) Hochman was the first born-deaf American to become a physician. At the age of 37, he entered Rutgers University medical school. He now practices in the Bay Area; 90 percent of his patients are hearing.

Kitty O’Neil, Texas and California (1946 ) As a stuntwoman in movies, O’Neil substituted for Lindsay Wagner in The Bionic Woman and Linda Carter in Wonder Woman. By 1981, she had set 26 world records on land, among them a speed record for a woman at 513 miles per hour in a three-wheeled rocket car, beating the old record by 200 mph.

Regina Olson Hughes, Nebraska and District of Columbia (1895–1993) Hughes started with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1930 and later was its botanical artist. In 1969, she moved to the Smithsonian Institute and worked as a contract illustrator for both offices. Her works are exhibited in several botanical museums and published in at least a dozen books, including one titled Common Weeds of the United States.

Juliette Gordon Low, Georgia (1860–1927) Deafened in her 20s, Low founded Girl Scouts in Savannah in 1912. The organization later grew nationwide. After the death of her husband, Low traveled alone all over the world.

Erastus Smith, Texas (1787–1837) Smith was a spy for General Houston in the Texan army that beat Mexico in a revolution. Deaf Smith County in Texas is named after him.

Boyce R. Williams, Wisconsin (1910–1998) Williams served 38 years in the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation and retired in 1983 as Chief, Deafness and Communication Disorders Branch, Rehabilitation Services Administration in the U.S. Department of Education. During his tenure, he helped start programs for deaf people, including the National Theatre of the Deaf, Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, and Captioned Films for the Deaf.

Tamika Catchings, Indiana (1979–) Her father was an 11-year National Basketball Association player, so she grew up in a basketball family. She played college basketball at University of Tennessee on the Lady Volunteers team. She was drafted by Indiana Fever of the Women’s National Basketball Association and has been named to WNBA All-Star Selection six times and All-WNBA Team six times.

William E. Hoy, Ohio (1862–1961) In 1887, Hoy was the first deaf person to play baseball professionally. He was the first and only outfielder to throw out three players at home base in one game and the first player to hit a grand slam home run in the newly founded American League. He is better known for inventing the signals now used by umpires.

Ronda Jo Miller, Minnesota (1978–) As an outstanding basketball player for Gallaudet University from 1997 to 2000, she was named to the NCAA Division III All-Decade Team. Scoring 2,656 points during her college career, she ranks third place on the Division III all-time scoring list. She was drafted by the Kansas City Legacy of the National Women’s Basketball League. She also played professionally for the Dallas Fury and Washington Mystics teams in the Women’s National Basketball Association.

Curtis Pride, Maryland (1968–) In high school, Pride was a Parade All-American selection and was the only American to be named as one of the top 15 soccer players in the world. He has been a professional baseball player for at least 17 years; most of his career was with the New York Mets. He is currently Gallaudet University’s baseball coach.

William Schyman, Illinois and Maryland (1930–) In 1950, as the most-feared player on the DePaul University basketball team, 6'5" Schyman was the first deaf hoopster to play on a major college varsity team. After signing with the Baltimore Bullets, he was the first deaf person to play professional basketball. He also played three years for the team that traveled with the Harlem Globetrotters.

Luther H. Taylor, Kansas (1876–1954) Taylor pitched for the famed manager John McGraw as a member of the New York Giants. His fastball helped the Giants win the National League pennant in 1904 and 1905. His ten-year ERA (earned run average) of 2.75 ranks favorably with today’s best pitchers. He was also a crowd-pleaser with his antics. Taylor, then working as a houseparent at the Illinois School for the Deaf (ISD), helped bring ISD student Richard Sipek into professional baseball.

Kenny Walker, Colorado and District of Columbia (1967–) After starring in high school football, Walker received a scholarship to attend the University of Nebraska. As a defensive end, he was the first deaf player named to AP’s All-America first team. He played for the Denver Broncos for two years and then in the Canadian Football League. At present he is the defense line coach at Gallaudet University.

Many football buffs are not familiar with the origin of the football huddle. Paul Hubbard, a star quarterback for Gallaudet College (1892–1895), did not want the opponents to see him sign plays to his teammates. He got his players to huddle around him, preventing any possible sighting of his visibly signed plays. The rest is history.