THE CRADLE OF THREE REVOLUTIONS

ST PETERSBURG, Petrograd, Leningrad

Along with its three names, the city variously known as St Petersburg, Petrograd and Leningrad, used to be called “the Cradle of Three Revolutions”. It was central to a succession of massive upheavals – the eventually failed empire-wide uprising of 1905, the February Revolution of 1917 that overthrew the Tsar, and the October Revolution that same year that began an experiment in total social transformation.1 Nobody calls St Petersburg this anymore. Over the last decades, it has become something of a forgotten city, though it is the fourth largest metropolis in Europe, after Moscow, Istanbul and London. Its eighteenth century canal-side streets look to the untrained eye like a tougher Copenhagen, yet rather than being lined by bicycles, they’re choked with traffic. A Petersburg “clan” dominates Russian politics, based around Gazprom and the secret services, but the city seems to have benefited little in terms of investment. Its piercing beauty coexists with a sharp carelessness. Aside from its revolutions, Petersburg is best known for a beauty that predates, and is irrelevant to, the revolution. At its heart is an ideal, diagrammatic plan, established in 1737, where the brittle classical edifice of the Admiralty, facing the river, marks the culmination of three grand boulevards, evenly departing from it – Ulitsa Gorokhovaya, Voznesensky Prospekt and Nevsky Prospekt, originally the Middle, Larger and Lesser Prospects. Each of these leads to the delicate spike of the Admiralty’s spire, although Nevsky also leads – if you turn right at its end – to the unforgettable dreamspace of Palace Square, best reached via the fictional route of the insurgent proletariat in Eisenstein’s October – down Nevsky, through the arch of the General Staff building, into the square and towards the Winter Palace. These are the most famous of Petersburg’s setpieces, but there are several. The central city, south of the Neva, is as uncanny as Venice, as calm as Amsterdam, with the streets overlooking the successive waterways of the Obvodnyy Canal, the Fontanka, the Griboyedov Canal, the Moika. There are the stark squares in front of the two Neoclassical cathedrals – Kazan Cathedral, a miniature Vatican, and Saint Isaac’s, in its proportion Parisian, but completely distinct in the exotic chromaticism of its red granite columns, almost black stone walls and golden dome. North of the Neva is the equally geometric ensemble of the “spit” of Vasilyevsky Island, and the Peter and Paul Fortress, whose restrained Baroque spire mirrors that of the Admiralty – power there, punishment here. Each of these would, absolutely anywhere else in Europe, be absolutely choked with tourists snapping away at this unearthly beauty. Here, in summer, there’s a few, mainly Chinese, but far less than outside far uglier buildings like Buckingham Palace or the Louvre. You can tell where tourism is happening, though, because someone will be yelling into a half-broken, feedback-emitting loudspeaker promising “excursions”. The place that erupted three times in strikes, factory occupations and insurrections was not defined by this perfectly calculated Enlightenment classicism, but by nineteenth-century suburbs of tall, crowded tenements, wooden slums, redbrick mills and heavy metal engineering works. Petersburg’s industry was monolithic, defined by a few enormous complexes employing thousands of people, staffed by workers whose grandparents were serfs. This made it an ideal city of what Bolshevik theorists called “Combined and Uneven Development”. Yet Petersburg is extremely “even” in its planned structure. That centre like an ideal Renaissance town plan come to life is surrounded successively by equally homogeneous quarters of the nineteenth century, the avant-garde 1920s, the Stalinist 1930s to 1950s, the prefabricated 1960s to 1980s. It is these last where new development is concentrated, because of the most influential Soviet legacy – the historical preservation of the entire city centre, which is sometimes circumvented, but never quite defeated, by property developers and their friends in government. Instead, developers cram ultra-high-density complexes of Postmodernist “luxury” flats, quickly built by brutally treated Central Asian migrant workers, into tight plots in the former industrial districts. It’s an unpleasant side-effect of conservation that the city government seem prepared to accept.

Cheap gas Copenhagen

Gorokhovaya to Admiralty

In memory of the Tsar, background, in memory of the workers, foreground

There are many traces of the revolution in the centre if you know where to find them. The cruiser Aurora, a volley from which was the signal for insurrection in October, still stands on the Neva, and was recently restored, although it currently downplays its revolutionary use. Plaques are sometimes to be found on the buildings occupied by the various revolutionary governments, like the Tauride Palace or the Smolny Institute. The most central monument is the exceptionally moving Field of Mars. It was commissioned from the young architect Lev Rudnev by the city’s Soviets (here, in its original usage as “workers councils”). It was originally a Tsarist parade ground near the river Neva, overshadowed since the late nineteenth century by the Cathedral of the Savior on the Spilled Blood, a florid, polychrome design of asymmetric onion domes, built in honour of Tsar Alexander II, who had been assassinated by revolutionaries in 1881. Rudnev’s design broke with these dominating surroundings completely, creating instead an anti-hierarchical space, a monument without monumentality – a processional route for revolutionary events, a burial ground for those killed in street fighting, and a place that could connect the victorious workers of Petrograd to the failed revolutionaries of the past. The texts on the monument’s tufa stelae, written by the Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky, link Petrograd to Paris: “to the crowds of Communards are now joined the sons of Petersburg”.2

The most interesting and enduring revolutionary legacy is more invisible – the Kommunalka. This hugely unequal and divided city’s apartments were audited and divided during the bloody Civil War that followed the Bolshevik seizure of power, with one result being extreme subdivision – several families in one huge, high-ceilinged imperial flat. Few outside Russia realise that many of the opulent apartment blocks in the centre are actually still Kommunalki, with a tangle of doorbell switches to each door. This has two results today. The neglect of these lush tenements is obvious, but inner-city districts have mostly not been fully gentrified, as the complexity of who owns what often deters investors. Defying conservation laws, some developers find it easier to just knock down and build “sham replicas” instead, dispersing the residents and owners in one fell swoop rather than negotiating with them.

It’s hardly utopian, but the persistence of the Kommunalka is nonetheless a definite revolutionary legacy in 2017, and remains popular with students and the young because of the fact you can live a stroll away from Palace Square for a decent rent, as long as you don’t worry about privacy or mod cons. This extends to the easiest and cheapest way to stay here as a visitor. For a fairly paltry sum you can sleep in a tiny cubicle with a plastic door with a cupboard-sized shower, right in the centre, managed, or not, by a skeleton staff and inhabited by lost people who thought they’d only just be staying here for a little while. On one visit, I waited an hour for someone with responsibility to turn up and give me the key I’d paid for in one of these. Eventually arriving, he took a look at my passport and smirked “this is not like Britain”. It’s not, though it helps not to know Russian – if you know only the little I do, you soon realise that the names and phone numbers chalked and stencilled on the pavements round here are those of sex workers.

The Lunatic Asylum

With the admirable exception of Catriona Kelly’s compendious and mindboggling 2014 book Shadows of the Past, St Petersburg after the end of the Second World War – during which the city was blockaded and starved nearly to death – is ignored in English-language histories. It was only really between the Sixties and the Eighties that the housing problem inherited in 1917 was seriously tackled, with the mass building of prefabricated housing – most of the results are nondescript, save the memorable Brutalist enfilades that line the canals in the north of Vasilyevsky Island. Perestroika Leningrad saw a late artistic flowering as a city of the post-punk avant-garde, via artists and musicians like Timur Novikov, Sergey Kuryokhin and Viktor Tsoi. It is also the hometown of Vladimir Putin, and his coterie of former secret servicemen. Its city government has been proudly reactionary – the recent law against “homosexual propaganda” was first tested out in Petersburg. The Northern Capital is among other things great evidence that start-ups, pop-ups and craft beer (at least one tap room in every city centre courtyard, it seems) do not a socially liberal city make.

A sham replica in progress

And despite all of this, the centre endures probably the best preserved, least damaged Neoclassical metropolis on Earth, and the central paradox of the revolution is that it left the place where it happened so completely intact. So for instance there is only one Constructivist building in the centre of Leningrad, in a city that was a centre for the avant-garde for decades. And it’s not accidental that the building in question is the Bolshoy Dom, the Big House, housing consecutively the NKVD, the GPU, the OGPU, the KGB, and currently the FSB, which means it’s in better condition than any building of its era, here or in Moscow. It was designed by Noi Trotsky and Aleksandr Gegello, and it is an unusual example of Constructivist architects – very talented ones – applying modernist principles directly to the instruments of dictatorship, with all the minimalism, plate glass and Americanist/Bauhaus references pulled into a hierarchical composition that is pure Lubyanka. Apart from the Metro stations, there’s very little Stalinist architecture here either. There’s a smattering of post-1991 buildings, and perhaps one reason why so few is that those that do exist are so appalling that they’re enormous evidence that the twenty-first century can do nothing of worth here – as in the “Regent Hall”, a daring assemblage of columns, mirrorglass and supergraphics.

The Big House

The neglect of the city centre also extends to the surprising quantity of industry that still exists inside it, long since expelled from Moscow. Obviously it doesn’t make it a healthier country or a more pleasant one to live in, but my north-west European eye is immediately pleased by the closeness of industry and urbanity here: you can take a leisurely stroll from submarines to Neoclassical institutes. You can find this a pretty short distance from the centre, as in the district around the typically delicate Neoclassicism of the Bobrinsky Palace, now the Faculty of Liberal Arts of the Smolny College (literally at the other end of the city from the famous Smolny Institute, formerly a girl’s school, that was the centre of 1917). The area is dominated by Petersburg’s main lunatic asylum, to the point where apparently this is shorthand for the area in general, though by now this refers to the backwater effect caused by the lack of a Metro station.3

Submarine, St Isaac’s

You can find a glass box with a rusty chimney emitting a strong smell of polish opposite a fine block of art nouveau (or as they called it here, Style Moderne) tenements for shipyard clerks from 1908, looking untouched for decades, coated in a thin layer of grime and dust, as is almost everything in St Petersburg, from the buildings to the cars. For all its grandeur and order, this is not a fastidious city, or, at least to the untrained eye, a rich one; you sense it’s a very, very long time since this was the Russian capital. The proximity of these different registers coincides with a seeming carelessness about which parts of it get restored and which don’t. Nearby is New Holland, a planned island enclave of warehouses, which has spent years rotting away quietly despite dozens of competing plans, some of them involving major architects such as David Chipperfield and Norman Foster, to transform it into a multifunctional hipster playground. In terms of the failure of any of these consecutive ideas to actually take form in reality, it could be compared to London’s Battersea Power Station saga, except that this is not a Thirties power station, but a UNESCO-listed ensemble of eighteenth-century classical buildings.

The NEP City: Narvskaya Zastava

In this showcase of planning, the first place to be specifically created by the Soviet planned economy is eclectic in style, straggling in form. South of the city centre is the Narva District – Narvskaya Zastava – a working-class district of wooden houses and tenements from before the revolution, clustering around the Putilov heavy engineering works, which provided the bulk of Bolshevik support in the revolution and Civil War (and at the end of it, moved towards opposing it, one of the reasons for the shift towards the mixed New Economic Policy, and the relative freedoms of the 1920s). From 1924 onwards, this district was rebuilt as a showpiece.4 The only structure here that gets mentioned in Petersburg’s many guidebooks is the Narva Gate, a green-painted triumphal arch, built both to celebrate victory over Napoleon and to provide a gateway to the city. After the area was replanned, it stood as the focal point for a huge and vague square, Ploshchad Stachek, Strikes Square. Almost everything around it is from the 1920s and early 1930s, the golden years of Soviet modernist architecture, the “Lost Vanguard”, as the photographer Richard Pare called them. There is nothing else, save for a Stalinist Metro station and the horrific 1812 Shopping Centre, which with its mirror-glass, fibreglass columns and clumsy imperial symbolism is all of the worst things about Nineties architecture in the city summed up. It faces the Gorky Palace of Culture, designed in 1925 by two of the most prolific Leningrad Constructivists, Alexander Gegello and Dimitri Krichevsky, on a fairly conventional stripped classical plan, slightly resembling the Berlin Volksbühne, only with much more glass, and a lack of any explicit historical references, opting instead for the expression of pure volume and mass. Next to it is a furniture store designed in 1930 by the same architects, which was when built a Technical College. It has a peculiar decorative fenestration, with the lower two sets of windows stepping downwards, in a clumsy bit of cubo-futurism. In the original drawings, these were ribbon windows, slashing dramatically downward. Evidently, the builders took one look at this and swiftly revised it to the interesting botch-job you can see now, where the limitations of a largely peasant building industry meet the vaulting ambitions of the architects, and cancel each other out.5 The rhetorical side of Strikes Square – the need to display revolutionary fervour while carrying out the post-revolutionary programme mural – comes in an exciting mural of 1965, by the painter and illustrator Rifkat Bagautdinov, depicting the revolutionary deeds of 1905 and 1917. It is in the “severe style” of the “Thaw”, so rather than being – as are the sculptural reliefs of the same events in the Metro station adjacent – an image of oppressive solidity and hierarchy, its figures are lively, energetic, with dramatically sketched factories and plotting revolutionaries, as if from a Khrushchev-era children’s book. Visiting the square once with the Polish writer Agata Pyzik, she insisted on a photograph in front of it, as a rare place where you can feel the presence of real revolutionary energies, a feeling that here is where it all happened, which you never quite get in the city centre. This is no doubt also what lies behind the moving short film by the St Petersburg neo-avant-garde group Chto Delat, Angry Sandwich People, where a group of people carry sandwich boards reading out a Brecht poem about the dying of revolutionary hope, appropriate for a celebratory proletarian space declining into a deindustrialised “ghetto”.6 It hinges on the central problem of this place – somewhere created out of revolutionary optimism and creative fervour that has fallen into a depopulated depression, unable to imagine any way out of its own predicament. It’s not really a square, Ploshchad Stachek, it’s more a large traffic space attached to Stachek Prospekt, another long, wide street, which may once have felt public when the traffic was minimal, but now – perhaps as intended – feels far more of an artery than a public utility. The buildings don’t feel as unified as they might, as to cross the road to get to them involves a certain amount of bravery; conceived as a unified ensemble, they don’t coalesce together like a square should. So over the road from the Gorky Palace of Culture is the relatively well-kept School for the 10th Anniversary of the Revolution, designed by Alexander Nikolsky, a pupil of Kazimir Malevich. It’s planned, arbitrarily but prettily, as a hammer-and-sickle, with a planetarium in the “hammer”. Over the entrance is the same symbol, in travertine, only with a tennis racket added to the objects. On the same side of the square is a building in far worse condition than any of the others – the Kirovsky Fabrika Kuchina, or Sergei Kirov District Factory Kitchen – after his 1934 assassination, the entire Narva District was renamed after the former boss of Leningrad. This is an incredibly ambitious building, the most brilliant and fearless of three designed by the “psycho-technical” ASNOVA School of architects. On each side are huge plate-glass windows, in the middle is one extremely long, Corbusian ribbon window, and beneath it are the high vitrines of a department store; perhaps this didn’t go down well in the Petersburg climate, but the actual fabric of the building seems fairly untouched, with additions being ad hoc and cheap rather than comprehensive, which at least doesn’t affect the actual fabric. The originality and confidence of the design is still astonishing, but logos have been bolted onto every available surface, and the concrete is clearly in dire need of repair. The roof terrace is now a green-pitched roof. Follow Stachek Prospekt further down, and you find some more ordinary housing of the avant-garde era, five storey buildings in “Zeilenbau” (line-building) arrangements, a prefiguring of Khrushchevki in scale and linearity. Cross here and you find the most surprising and all-round wonderful thing on Stachek Prospekt: the Traktornaya Ulitsa housing scheme, by Gegello, Krichevsky and Nikolsky, of 1926. It is Petersburg classicism gone cubistic, opened up, chopped up only seemingly at random, without the divide between the imposing front and the sordid backside that, as we will see, defines actual Petersburg classicism. While other compromises between Constructivism and classicism are just that – compromised, caught between two styles, leading to intriguing confusions – this scheme has total confidence about itself. It does many of the things that Seventies/Eighties Postmodernist housing would try and do – a teasing morphing of a familiar local “vernacular” into something palpably new, only, for reasons both political (i.e. an unsurprising lack of nostalgia for Tsarism in early Bolshevik Petrograd) and aesthetic (Petersburg’s historic architecture is already abstract and dreamlike) it actually works. It’s as neglected as everywhere else, but wears the knocks well.

Spires of Petersburg

Bobrinsky Palace

Illustrating Revolution

The Factory Kitchen

Terminating the square to the south is the largest of the Ploshchad Stachek buildings – when it was built in 1932, perhaps the largest of modernist buildings anywhere, here or elsewhere – is the local town hall, or again, post-assassination, Kirov District Soviet, designed by Noi Trotsky, near-namesake of the more straightforwardly assassinated former leader of the Petrograd Soviet. In front is the first of many statues of Kirov, this one with the extraordinary quote on its plinth:

Comrades, many centuries ago a great mathematician dreamed of finding a point of support, which if leaned upon, could turn the globe. Centuries have passed, and this support is not only found, it is created by our hands. It will not be many years until we, basing ourselves on the achievements of socialism in our Soviet land, turn both hemispheres on the path to Communism.

It is heady rhetoric for a public square to support. The Soviet itself is a very long block in concrete and granite, with strip windows leading to a curved cruise-ship corner on one side, and a thrillingly pure Constructivist tower on the other, with an illuminated hammer and sickle. Note that viewed from the square, the chimney of the Putilov Works is symmetrically aligned with the Soviet. Round the back of the tower is a slightly later extension, including the disused Progress Kino, where the lack of ornament and modern materials (somewhat dour, in this case) is replaced with granite mouldings for no perceptible architectural reason, other than a certain Stalinist horror vacui. Walking around this neglected space is uncomfortable. Opposite the closed cinema is the draft board – when I first walked round here in 2010 the loophole for university students that exempted them from conscription (and the horrendous hazing rituals that usually go with it) had just been closed, and there were stories of the militia dragging young men from the Metro and forcing them to the draft boards to enlist.

Kirov District Soviet

Part of the Narva District’s rebuilding was a new park. In the early 1950s, a statue was built here of Communist youth. On the flag they’re holding is the only surviving graven image of Joseph Stalin on permanent display in a public space in any major Russian city, until the annexation of Crimea in 2014 saw a wave of new depictions of the despot. Here, it’s like a little secret, the unacceptable face of the Soviet power that built this impressive, if decaying, square.

Backwards Through History on Vasilyevsky Island

One of the places foreigners were expected to stay in the late Soviet period, long before unobserved foreigners could get themselves a seedy room on Gorokhovaya, was the Hotel Pribaltiyskaya, at the furthest edge of the city, where Vasilyevsky Island meets the Baltic. This was an early bit of post-industrial regeneration, built at the far corner of an island which had since the early eighteenth century been one of Petersburg’s working districts, home of the fleet, the shipyards, and much of the industry. The mammoth hotel is one part of a riverside ensemble built in the late Brezhnev era, a heavy, high modernist district of concrete and glass, set alongside locally specific things such as canals and the Gulf of Finland. The hotel itself is mammoth in scale, clearly expecting to deal with enormous quantities of tourists and so scooping them up away from the centre and putting them in somewhere where they can have a nice sea view and... not much else. How they were meant to get there is mysterious. On architectural grounds, the St Petersburg Metro is one of Europe’s finest, from the heroic Stalinist narrative of Line 1, to the 1980s Futurism of Line 4; but unlike in Moscow, it is totally inadequate to the city’s transport needs. So to get to the Pribaltiyskaya Hotel, you must first get yourself to Primorskaya Metro, then take a bus, a cab or, in the summer, walk. When you leave the station, you find something else that is no longer quite so obvious in Moscow – the effects of the “informal” commerce that arose out of governmental corruption and organised crime in the early 1990s. The station is in a collection of gimcrack little buildings crowding round the station, some of them semi-permanent in appearance, others recognisably the impromptu kiosks they once were; there are Western brands like Burger King, along with opticians, pharmacists, and all the things a dense modern city needs, and which the Soviet Union provided only at spacious distances from each other. In a basement here is a Metro museum, which celebrates both the system itself and the many that St Petersburg’s engineers have constructed elsewhere, in the USSR and in Central Europe – look closely at a tube carriage in Warsaw, Sofia or Budapest and you’ll probably see the inscribed words “METROWAGONMASH-SANKT PETERBURG”

A Grin without a Cat

When outside the station, you can see what the Soviet economy and Soviet architecture did when it reached the level of mechanisation and standardisation that architects only dreamed of when they built Narvskaya Zastava. Around you is a wholly planned district of systembuilt housing, much of it by the in-house department in Leningrad. Many are examples of a relatively popular system, the ILG-600, known in these parts as the “ship houses”, a model constructed in hundreds from 1965 to 1977, fairly sleek and elegant as these products went, with a strong horizontality that led to its nickname. According to Dmitrij Zadorin’s catalogue of Soviet standardised housing, there was such incredulity that the Soviet building industry could produce something of this quality that it was assumed to be a mere copy of a Polish system (it wasn’t).7 Past the Ships, you find another ensemble, this one made up of one-offs, prefabricated again, to be sure, but designed only for this site and no other. Facing either side of an embanked canal, there are two distinct types, horizontal and vertical. The horizontal step away from the water, with shops on the ground floor and grand, Stalinist-style archways to the courtyards behind. Their Gothic monumentality marks them out as being from the very late Brezhnev era, when the domineering imperial aesthetics of Stalinism made a comeback, even if in prefabricated form. The vertical part is much more interesting – a series of point blocks, strongly Brutalist – a style not that common in the USSR, given it involved exacting concrete work – and expressive, hauled up on angled little pilotis and faceted into a sculptural, zig-zag surface. Marching down the canal to the Gulf of Finland, they’re strangely idyllic. In summer, people lounge around here with their clothes off, enjoying the opportunity to do in a city where autumn and spring is grey, and winter is punitive.

Welcome to Vasilevsky Island

ILG-600

Duller prefabricated blocks lead to the hotel, which is in a similarly Brutalist, high-end manner to the canal-side vista, with a big statue of Peter the Great overlooking it. On either side of it is new development, and here you learn something important about Petersburg’s urban geography. The concomitant of the lack of development in the worn but unimpeachable UNESCO-listed centre – a listing the city nearly lost, when Gazprom proposed to build a skyscraper in the suburbs that would be visible from the Neva embankment – is intensive building in places like Vasilyevsky Island and further out. Here, given that the lack of a Metro connection means a bus can take you into town in fifteen minutes, property speculation has been especially rife. So if you stand on the high steps of the Pribaltiskaya Hotel and look down the Prospekt that leads to it, you can see the new Petersburg taking shape. It consists of high-density complexes with prefabricated “stone” ornament in such a manner as to look back both to the Stalinist city and to the imperial tenement type; they are oriented to the street and punctuated with towers, with little public space but car park courtyards, and are frequently gated communities. They’re quite traditionalist in form, which puts them very close to the neo-Victorian “New Urbanism” movement advocated by Charles Windsor and the Walt Disney Corporation. Advertisements on the Metro sell these as the “Old Fortress”, where the industrialised blocks are gazed at by cartoon nineteenth-century figures.

Brezhnev’s Gotham

The Canals of Leningrad

A walk around Vasilyevsky Island, though, is gratifying – everything has happened here at one point or another. When you’re past the New Urbanism, you’re in an extremely dense working-class district of very tall tenements, their seven storeys a sign of just how teeming this city must have been when the revolution happened. They’re all a short walk away from the workplaces – the shipyard and the fleet. There is an oligarch’s art museum round here, but more interesting is the Submarine Museum, where a large sub is suspended on a plinth, and you can climb into the “D-2 Submarine Narodovolets” and have a wander around for a small fee. Next to this is the Sea Station, where arrivals by boat from Finland and further afield still disembark; the porousness of this port was one of the things that kept the city unusually abreast of Western trends in the Soviet era, with pop records, for instance, coming through here before everywhere else. It is, like much of Vasilyevsky Island, an unusually strong building for Seventies Russia, Brutalist in form and Petersburgian in content, right down to the high and thin copper steeple.

The New St Petersburg

Hidden within the tenements are several Constructivist buildings – not a whole planned space, as in Narvskaya Zastava, but scattered works. The elegantly bare tenements run along numbered, un-named streets, the projected sites of unbuilt canals, which then give way very suddenly, to more new Neoclassical high-rises, one with the subtle name of “Financier Apartments”. In the shadow of these is the Kirov Palace of Culture, designed by Noi Trotsky in the early Thirties. Architecturally, it is another work at the exact midpoint between Constructivism and Stalinist Neoclassicism, something that seems to have been very common here, as an alternative to the opulent kitsch being built at the same time in Moscow (aptly, it is mostly limited to the aptly named Moskovsky District, the city’s southern entrance, a parade of giant streets, massive Neoclassical housing complexes and yawning ceremonial plazas). At the building’s back, is crisp and clear modernism, and at the front, a complex composition indebted to the abstract painting of Kazimir Malevich has been encased in rustication, smothered in detail – but you can still recognise this as Constructivism – the asymmetrical massing and Suprematist interlocking planes are unmistakeable. It is also quite vast, with the tacked-on stone crumbling and some of the windows boarded-up. It faces a nice if scrubby green.

Sea Station

Across this green is a Constructivist Factory Kitchen, one of the three in the city designed by ASNOVA architects. In Richard Pare’s monumental photobook The Lost Vanguard, he finds this building completely stripped, with straw reinforcement sticking out of the steel struts, with a group of homeless Petersburgers sitting round a bonfire made out of the building’s remains. In that image, Soviet modernism collapses back into medieval Russia. I was so impressed by this image that I used it in my first book, and span some rash theories out of it. So imagine my surprise to not find a tumbledown wreck, but a cleaned up and restored local centre. Needless to say, this has not been done with a great deal of historical care. The restoration of the actual building isn’t too awful, but one wing of it has been covered with a metal screen, which promises a “Fashion Gallery” (in English) inside. On asking, it turns out a Fashion Gallery is a shopping mall. It’s funny – as in, both depressing and ironic – to see a device like this used here. These metallic skeins were used by high-tech architects in the Eighties who were utterly in hock to Russian Constructivism – and now they’re used to encase one of the few actual Russian Constructivist buildings left. Even so, it is a challenge to an idea about Soviet modernism that Pare’s book was an early and influential example of, and which I compounded in my own.8 Left as a ruin, it is an image which unites 1917 and 1991, Eisenstein and Tarkovsky, optimism and collapse, old wooden-built Russia and peasant futurism. Unfortunately enough, that interpretation was bollocks. Most “ruins” here are inhabited, and even those that are not, in cities where money is to be made, like St Petersburg, can quickly be brought back into useful use. Ruins, at least when war and disaster hasn’t taken place, tend to exist more in the head than in reality, a romantic idea of the effects of the Soviet collapse belied by the bright and tacky actuality.

Rusticated Constructivism – the Kirov Palace of Culture

Not Actually Ruined

One Chernikhov Building, for sale

Of all the architects the high-tech architects of the Eighties were in the deepest hock to, the foremost might have been the “Soviet Piranesi”, Iakov Chernikhov. He has a building just round the corner from the Factory Kitchen, which is unusual. Most books about Chernikhov note that, while he was working on his incredible 1933 brochure Architectural Fantasies, he was designing several industrial buildings. The only one of these to my knowledge that has been positively identified is this, and one of his dynamic drawings of it survives. It’s a factory just next to the docks on the Neva, and is the other side of Piranesi – those images of noble buildings overcome by various kinds of vegetation. It looks like one of H.G. Wells’ Martian tripods beached on the Neva after catching cold, with its eyes boarded up, a quiff of green weeds on its head. The sign draped on the building when I first visited in 2010 said “For Sale”, but there have been no takers. Unlike with the Factory Kitchen, repeated visits have only confirmed the ruination, with the building unsold and the trees growing out of its Martian forms only getting bigger. But just next to it is a working shipyard, with the cranes of the Neva that inspired Tatlin to create the Monument to the Third International still darting about, and the icebreaker Krasin docked underneath.

The Petrograd Side

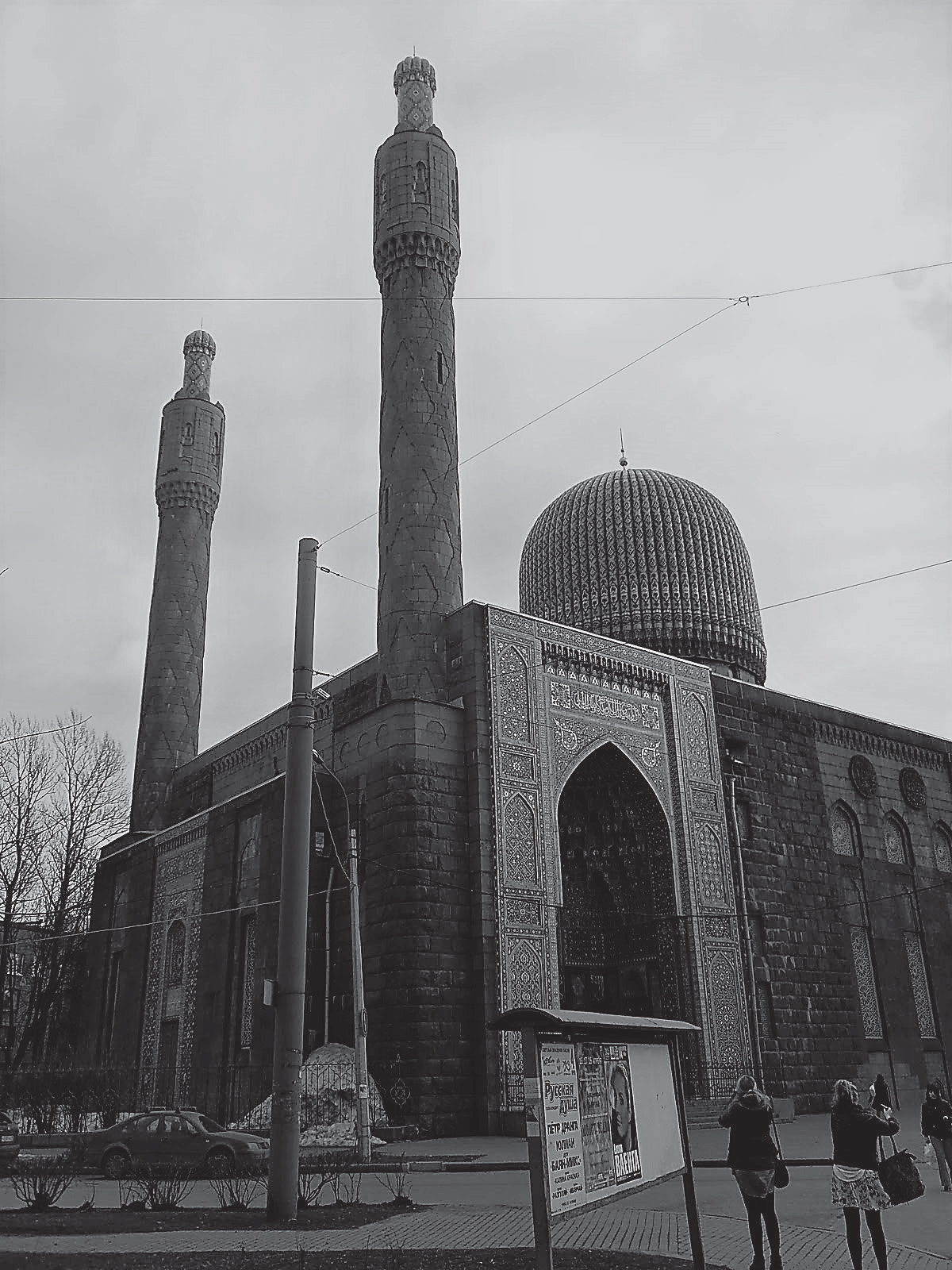

While “St Petersburg” evokes autocracy and post-91 restoration triumphalism and “Leningrad” Stalinist leader-idolatry, “Petrograd” – the city’s name from 1914 to 1924 – summons up images of the Petrograd Soviet, the city that called itself “Petrocommune” during the Russian Civil War, and perhaps the city that rebelled again in 1921. The Petrograd district itself, north of the Neva, meanwhile, is a mostly an art nouveau/eclectic area where you could easily be in any other big city of the late nineteenth century – Vienna more than Berlin, perhaps – as opposed to the oneiric Neoclassicism of the central canal-side areas. If you cross the river at the Troitsky Bridge, though, the first building you’ll come to was once the Collective House of the Society of Former Political Exiles, built at the turn of the Thirties. It’s International Style modernism rather than Constructivism, Gropius in granite style. Few of these former political exiles – usually Old Bolsheviks, sometimes Anarchists, Mensheviks or SRs – would survive the Thirties. The October Revolution emerged from some strange places. One such place, the Kshesinskaya Mansion, was designed for a ballerina in the Imperial Ballet by Aleksandr Von Gogen in 1904-6 – an iron, tile and glass Jugendstil jewel that just happened to be the headquarters of the Bolsheviks throughout 1917. The ballerina in question was subject of the “controversial” recent film Matilda, whose suggestion that Nicholas II indulged in extramarital sex scandalised the Orthodox Church, who venerate him as a saint. Next door is something originally named the “Railway Transportation Academy Named after Comrade Stalin”, designed by G.A Simonov in 1931 – a projecting front and a long curve round the back. It’s another instance of Petersburg’s domestication of Constructivism, leaving it close to a kind of Scandinavian modernised classicism. Not that all the pre-revolutionary buildings around are so sober: the Central Mosque, designed at the same time as the mansion, combines thick, knobbly rustication and obsessively complex detail, in a manner that bridges the mosques of Samarkand and the Moscow buildings of the 1930s. This strange collection of buildings then gives way to a grand boulevard of eclectic edifices, a continuous nineteenth-century city of mass, grandeur and pomp. What is perhaps more interesting than the façades – some of which are indeed very pretty – is what happens at the back. As much rent as possible was squeezed out of the spaces, with long systems of courtyards within courtyards, in which you will find Seventies glass cage lifts, random lumps of ice (spring only), the ubiquitous broken pipes, and gigantic cracks running down the buildings. It’s fascinating, a half-hidden seedy second city behind the grand frontage, and one which you can walk through almost continuously for some time, until you eventually find a courtyard that has been gated off. Up the road a fair bit from here is the Lensoviet Palace of Culture, another Petersburg building that began Constructivist and ended up a strange melange, with plate-glass walls and asymmetries under sculpture and stone. It’s a very worthwhile accidental style, this, a forgotten form of imposing, compromised modernism maybe more akin to Auguste Perret or the Portland stone-modern of the Forties in the UK than the full-blown Stalinist fantasias you find in Moscow – there’s a dialectical standoff between the openness and irregularity of the original plans and the brooding masonry they’re wrapped in. The finest example of this “postConstructivist” architecture is the Collective House for Workers at the Lensoviet Palace of Culture, a luxury complex (including servant’s quarters – you didn’t get that at the Kshesinskaya Mansion in 1917), designed by E. A. Levinsohn and Igor Fomin in 1931, finished four years later. The space inside the housing scheme is full of sculptural games, with proper Constructivist ramps jutting out of it, and a pavilion at the back which is randomly bashed-up, with varying kinds of political and puerile graffiti all over it. The building’s plan is like something by Lubetkin, all playful games with canopies, pilotis and curves, but the finished building is defined by a mix of granite and concrete (now spalling) which makes its games feel more Kafkaesque, deliberate puzzles in an authoritarian space. The writer who actually guards it, in a 1950s statue, is Nikolai Gogol.

The Society of Political Prisoners

Samarkand on Baltic

Mansion of Insurrection

Spring

Postconstructivist luxury flats

Next to it, a more straightforwardly Constructivist office building – for the film industry, and originally going by the very sexy name Lenpolygrafmash – seems impossibly light and cheerful by comparison with all this murkiness. A longer walk to the west of here will take you to another postConstructivist scheme, the Svirstroy Housing Complex, finished as late as 1938, in bare concrete and red render. It has a notably un-Stalinist simplicity, but with lots of highly un-Constructivist monumental symmetry. Staring at this in 2010 I spotted for the first time a post-Soviet commonplace: the glass infilling of balconies, which is something done here, I was told, in order to create a free second refrigerator. At the corner of each of the building’s wings there’s a little abstract sculpture, a memory of Lipschitz or Gabo, stuck onto it. Finding public abstract art as late as 1938 on an apartment complex is unexpected, given how clear we like to imagine the divide between modernism and Stalinism to be. But the postConstructivist architecture of St Petersburg complicates those boundaries, showing ways in which the apparently distinct “cultures” of Soviet aesthetics could be reconciled. A mile or two from this (originally) bourgeois district is a redbrick industrial area of cotton mills and workers’ housing, a fairly accurate reproduction of Ancoats, only with much taller houses. Even here, some of the mills have been transferred to property development – in one row, some are derelict, some are loft conversions. One of the mills has a little plaque outlining how the workers won some sort of award for heroic socialist labour in the mid-1960s. Although it isn’t as inadvertently peculiar as the monument to children who died in the October Revolution – I had thought the unusual thing about the October Revolution was that nobody died in it (most unlike the civil war that followed). Sceptical local opinion has it that the lack of a monument to children just needed to be filled.

There’s one main reason why anyone would come here for architecture. Erich Mendelsohn’s Red Banner Textile Factory is merely one part of a giant textile works, but it’s from an entirely different planet to the rest. It’s often forgotten that the USSR invited projects in the Twenties from the most famous modernist architects – and while schemes by Marcel Breuer, Gropius, Perret, Poelzig, Lurcat and many others came to little, there are two enormous buildings by major modernist architects in each capital – one in each, specifically, with Corbusier’s Centrosoyuz in Moscow the other. Mendelsohn had the job taken away from him mid-way through construction in 1926, but the boilerhouse was completed entirely to his design. It is, like the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill or the Petersdorff Store in Breslau, one of Mendelsohn’s sleek cruisers, a giant ship of red and yellow hurtling somewhere indefinable, far more massive than it looks in photographs. Even then, it’s part of a larger entity. A classically Fordist grid-like daylight factory surrounds the boilerhouse, now derelict, with the odd room turned over to various ad hoc light industries. Oddly enough those hanging around there when I visited didn’t seem especially surprised to see a fleet of English-speaking people with cameras descending upon it. Most unusually, however, just adjacent to the Red Banner factory is a decent new building, a moderate modernist sports hall and Jewish Cultural Centre – nothing special, just a decent small brick building which somehow managed to get built without explicit historical references or “gob-ons” of any sort.

Textile cruiser

There are two major historical museums on the Petrograd side. One of them is in one of those flamboyant bourgeois apartment blocks, though it concerns a man who was not himself bourgeois. In summer 2016 I walked to the S.M. Kirov Memorial Museum past election posters for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, whose unabashed nostalgia and nationalism represents the official continuation, or terminus, of October round these parts. At 26-28 Kamenoostrovsky Prospekt is a handsome block of granite apartments, built in the early 1910s for an intelligentsia clientele of “government officials, celebrated writers, journalists and architects”.9 After 1917, the block was, like all other private apartment blocks, nationalised and turned into Kommunalki. In 1926, though, it was reorganised again as a block for… government officials, celebrated writers, journalists and architects. Among them was the head of the city government, Sergei Kirov, a street-fighting working-class Bolshevik who had been part of Stalin’s personal circle in the Caucasus. He and his family got five rooms. The house-museum dates from the Fifties – originally, his artefacts were kept down the road in the Museum of the Revolution. Nonetheless, the artifice is not obvious – it looks in places like he’s only just gone out for his fateful 1934 walk. You can see hunting paraphernalia and many stuffed animals, a prodigious library, a bourgeois sense of good taste, and separate beds between him and his wife. Now, how you assess Kirov’s level of privilege depends on whether you assess him by the standards of the early Bolsheviks, eating gruel and burning their books to survive the Civil War,10 in which case it is grossly opulent, or by that of world leaders in the 1930s, in which case it is modest. Judging by his taste, as exhibited here, Kirov – no matter how much avant-garde architecture was built under his rule of the city – was no Constructivist. This is a deeply bourgeois apartment, which you could imagine being owned by a particularly bookish French general. There are moments of bad taste that would make a modernist wince, right down to the treated, sepia-toned photographs of Lenin and Stalin, looking like the dreamy, ghostly pics on an Edwardian Valentine’s Day card.

The revolutionary’s drawing room

There is quite some contrast between this matter-of-fact slice of Soviet bureaucratic life, and the depiction of the revolution now in Ksheshinskaya’s Palace. When I first visited in 2010, you still had to wear plastic slippers and photos were strictly forbidden. The collection of revolutionary memorabilia had, at some point in the Nineties, been supplied with new captions telling you how awful the Bolsheviks really were. Currently, these rooms coexist with a more nuanced but still schizophrenic depiction of revolutionary events, after a recent expansion and restoration. Now, one room will tell you about Ksheshinskaya, another still replicates the Bolshevik Central Committee’s offices, another gives a potted history of Soviet housing in the city. Most pertinent of all is a permanent exhibition on the Duma, the rigged parliament that Tsar Nicholas II conceded after the first of the “three revolutions” in 1905. It is aptly placed alongside the equally powerless current Russian parliament that bears the same name. You might, in all of this, miss the most important thing of all – the expropriation of the rich, their luxuries transformed into a base for plotting out the parameters of a new and better kind of society. The streets of Petersburg have abundant evidence of how that ended up; but they also show, still, why it was and is so very desirable.