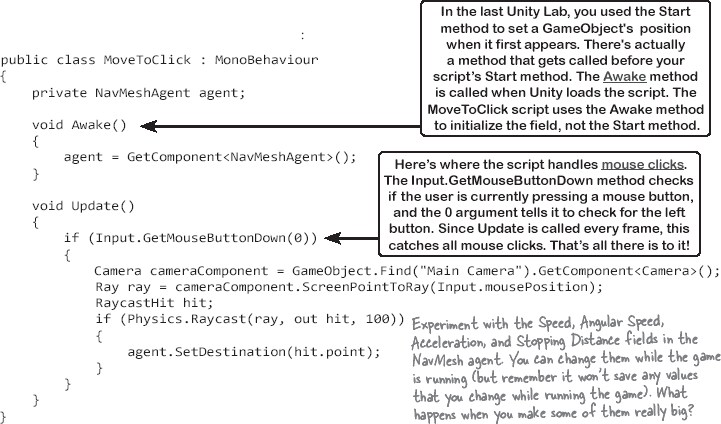

Part V. Unity Lab 5: Raycasting

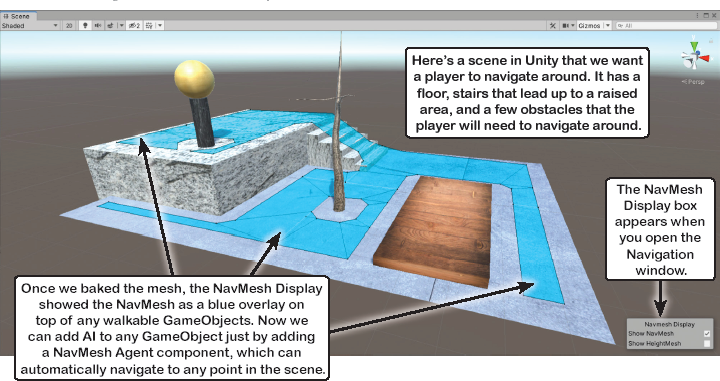

When you set up a scene in Unity, you’re creating a virtual 3D world for the characters in your game to move around. But in most games, most things in the game aren’t directly controlled by the player. So how do these objects find their way around a scene?

The goal of labs 5 and 6 is to get familiar with Unity’s pathfinding and navigation system, a sophisticated AI system that lets you create characters that can find their way around the words that you create. In this Lab, you’ll build a scene out of GameObjects and use navigation to move a character around it.

In this Unity Lab, you’ll use raycasting to write code that’s responsive to the geometry of the scene, capture input and use it to move a GameObject to a point that the player clicked. And just as importantly, you’ll get practice writing C# code with classes, fields, references, and other topics we’ve learned about.

Create a new Unity project and start to set up the scene

Before you begin, close any Unity project that you have open. Also close Visual Studio—we’ll let Unity open it for us. Create a new Unity project using the 3D template, set your layout to Wide so it matches our screenshots, and give it a name like Unity Labs 5 and 6 so you can come back to it later.

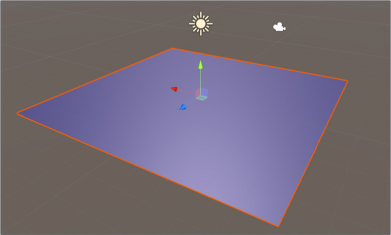

Start by creating a play area that the player will navigate around. Right-click inside the Hierarchy window and create a Plane (3D Object >> Plane) and name your new plane GameObject Floor.

Right-click on the Assets folder in the Project window and create a folder inside it called Materials. Then right-click on the new Materials folder you created and choose Create >> Material. Call the new material FloorMaterial. Let’s keep this material simple for now—we’ll just make it a color. Select Floor in the Project window, then click on the white box to the right of the word Albedo in the Inspector.

In the Color window, use the outer ring to choose a color for the floor. We used a color with number 4E51CB in the screenshot—you can type that into the Hexadecimal box.

Drag the material from the Project window onto the Plane GameObject in the Hierarchy window. Your floor plane should now be the color that you selected.

Note

Think about it and take a guess. Then use the Inspector window to try various Y scale values and see if the plane acts the way you expected. (Don’t forget to set them back!)

Note

A Plane is a flat square object that’s 10 units long by 10 units wide (in the XZ plane), and 0 units tall (in the Y plane). Unity creates it at point (0, 0, 0), the center of the plane. Just like our other objects, you can move a plane around the scene by using the Inspector or the tools to change its position and rotation. You can also change its scale, but since it has no height, you can only change the X and Z scale—any number you put into the Y scale will be ignored.

The objects that you can create using the 3D Object menu (planes, spheres, cubes, cylinders, and a few other basic shapes) are called primitive objects. You can learn more about them by opening the Unity manual from the Help menu and searching for the Primitive and placeholder objects help page. Take a minute and open up that help page right now. Read what it says about planes, spheres, cubes, and cylinders.

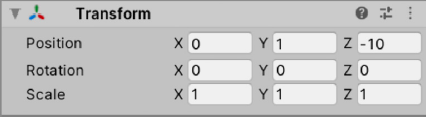

Set up the camera

In the last two Unity Labs you learned that a GameObject is essentially a “container” for components, and that the Main Camera has just three components: a Transform, a Camera, and an Audio Listener. And that makes sense, because all a camera really needs to do is be at a location and record what it sees and hears. Have a look at the camera’s Transform component in the Inspector window.

Notice how the position is (0, 1, -10). Click on the Z label in the Position line and drag up and down. You’ll see the camera fly back and forth in the scene window. Take a close look at the box and four lines in front of the camera. They represent the camera’s viewport, or the visible area on the player’s screen.

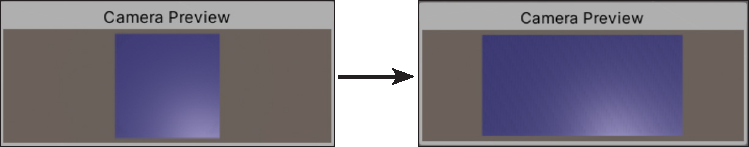

Move the camera around the scene and rotating it using the Move Tool (W) and Rotate Tool (E), just like you did with other GameObjects in your scene. The Camera Preview window will update in real time, showing you what the camera sees. Keep an eye on the Camera Preview while you move the camera around. The floor will appear to move as it flies in and out of the camera’s view.

Use the context menu in the Inspector window to reset the Main Camera’s Transform component. Notice how it doesn’t reset the camera to its original position—it reset both the camera’s position and rotation to (0, 0, 0). You’ll see the camera intersecting the plane in the Scene window.

Now let’s point the camera straight down. Start by clicking on the X label next to Rotation in the camera’s Transform inspector and dragging up and down. You’ll see the viewport in the camera preview move. Now use the Inspector window to set the camera’s X rotation to 90 to point it straight down.

You’ll notice that there’s nothing in the Camera Preview anymore, which makes sense because the camera is looking straight down below the infinitely thin plane. Click on the Y position label in the Transform component and drag up until you see the entire plane in the Camera Preview.

Now select Floor in the Hierarchy window. Notice that the Camera Preview disappears—it only appears when the camera is selected. You can also switch between the Scene and Game windows to see what the camera sees.

Use the Plane’s Transform component in the Inspector window to set the Floor GameObject’s scale to (4, 1, 2) so that it’s twice as long as it is wide. Since a Plane is 10 units wide and 10 units long, this scale will make it 40 units long and 20 units wide. The plane will completely fill up the viewport again, so move the Camera further up along the Y axis until the entire plane is in view.

Note

You can switch between the Scene and Game windows to see what the camera sees.

Create a GameObject for the player

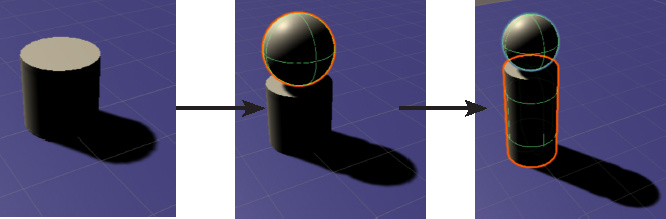

Your game will need a player to control. We’ll create a simple humanoid-ish player that has a cylinder for a body and a sphere for a head. Make sure you don’t have any objects selected by clicking the scene (or the empty space) in the Hierarchy window.

Create a Cylinder GameObject (3D >> Cylinder)—you’ll see a cylinder appear in the middle of the scene. Change its name to Body, then choose Reset from the context menu in the Transform component to make sure it has all of its default values. Next, create a Sphere GameObject (3D >> Sphere). Change its name to Head, and reset its Transform component as well. Each of them will have a separate line in the Hierarchy window.

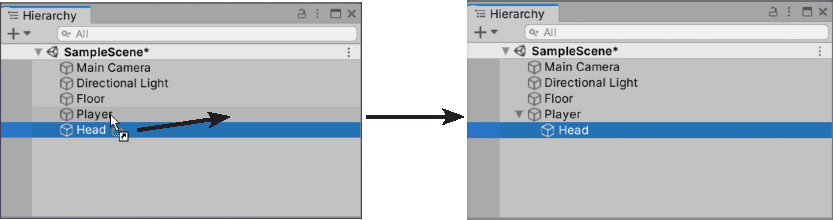

But we don’t want to separate GameObjects—we want a single GameObject that’s controlled by a single C# script. This is why Unity has the concept of parenting. Click on Head in the Hierarchy window and drag it onto Player. This makes Player the parent of Head. Now the Head GameObject is nested under Player.

Select Head in the Hierarchy window. It was created at (0, 0, 0) like all of the other spheres you created. You can see the outline of the sphere, but you can’t see the sphere itself because it’s hidden by the plane and the cylinder. Use the Transform component in the Inspector window to change the Y position of the sphere to 1.5. Now the sphere appears above the cylinder, just the right place for the player’s head.

Now select Player in the Hierarchy window. Since its Y position is 0, half of the cylinder is hidden by the plane. Set its Y position to 1. The cylinder pops up above the plane. But notice how it took the Head sphere along with it. Since Head is nested under Player, moving Player causes Head to move along with it because moving a parent GameObject moves its children—in fact, any change that you make to its Transform component will automatically get applied to the children. If you scale it down, children will scale, too.

Switch to the Game window—your player is in the middle of the play area.

Note

When you modify the Transform for a GameObject that has nested children, the children will move, rotate, and scale along with it.