Part VI. Unity Lab 6: Scene Navigation

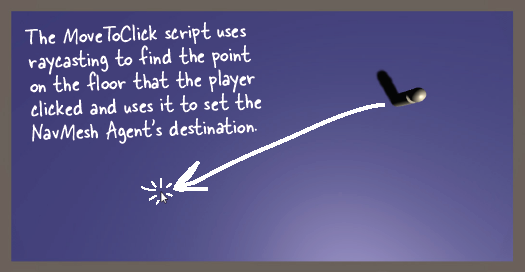

In the last Unity Lab, you created a scene with a floor (a plane) and a player (a sphere nested under a cylinder), and you used a NavMesh, a NavMesh Agent, and raycasting to get your player to follow your mouse clicks around the scene.

Now we’ll pick up where the last Unity Lab left off. The goal of this lab is to get familiar with Unity’s pathfinding and navigation system, a sophisticated AI system that lets you create characters that can find their way around the words that you create. In this Lab, you’ll build a scene out of GameObjects and use navigation to move a character around it.

Along the way you’ll learn about useful tools: you’ll create a more complex scene and bake a NavMesh that lets an agent navigate it, you’ll create static and moving obstacles, and most importantly, you’ll get more practice writing C# code.

Let’s pick up where the last Unity Lab left off

In the last Unity Lab, you created a player out of a sphere head nested under a cylinder body. Then you added a NavMesh Agent component to move the player around the scene, using raycasting to find the point on the floor that the player clicked. In this next Unity Lab you’ll pick up where the last Lab left off. You’ll add GameObjects to the scene, including stairs and obstacles so you can see how Unity’s navigation AI handles them. Then you’ll add a moving obstacle to really put that NavMesh Agent through its paces.

So go ahead and open the Unity project that you saved at the end of the last Unity Lab. If you’ve been saving up the Unity Labs to do them back to back, then you’re probably ready to jump right in! But if not, take a few minutes and flip through the last Unity Lab again—and also look through the code that you wrote for it.

Note

If you’re using our book because you’re preparing to be a professional developer, being able to go back and read the code in your old projects and is a really important skill – and not just for game development!

Add a platform to your scene

Note

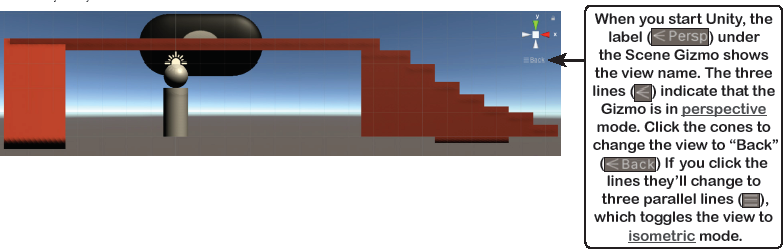

Sometimes it’s easier to see what’s going on in your scene if you switch to an isometric view. You can always reset the layout if you lose track of the view.

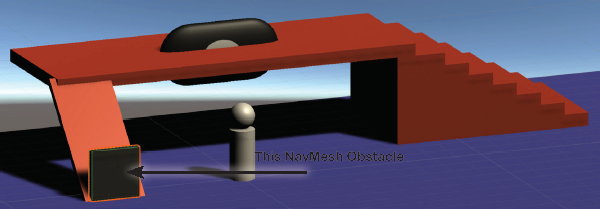

Let’s do a little experimentation with Unity’s navigation system. To help us do that, we’ll add more GameObjects to build a platform with stairs, a ramp, and an obstacle. Here’s what it will look like:

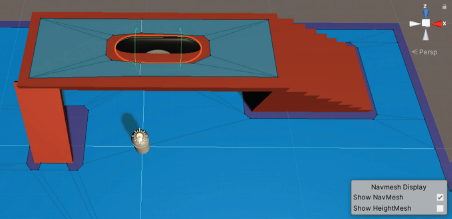

It’s a little easier to see what’s going on we switch to an isometric view, or a view that doesn’t show perspective. In a perspective view, objects further away look small, while close objects look large. In an isometric view, objects are always the same size no matter how far away they are from the camera.

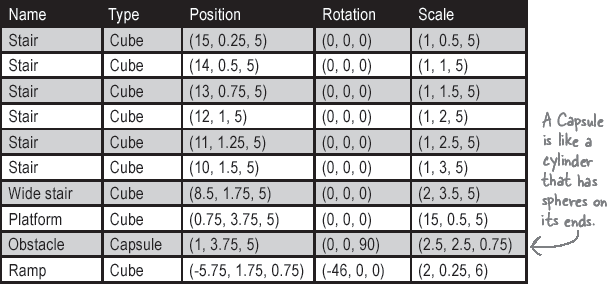

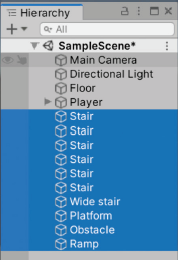

Add ten GameObjects to your scene. Create a new material called Platform in your Materials folder with albedo color CC472F, and add it to all of the GameObjects except for Obstacle, which uses a new material called 8 Ball with the 8 Ball Texture map from the first Unity lab. This table shows their names, types, and positions:

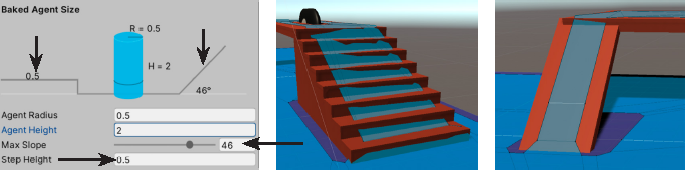

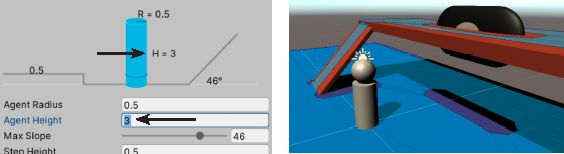

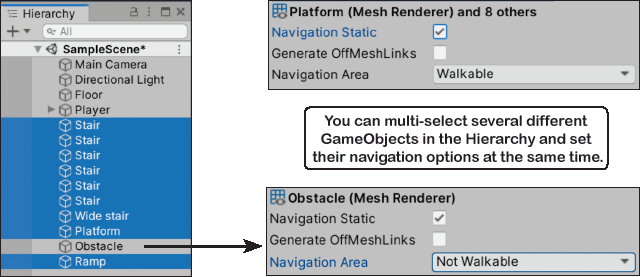

Use bake options to make the platform walkable

Use shift-click to select all of the new GameObjects that you added to the scene, then use control-click (or command-click on a Mac) to deselect Obstacle. Go to the Navigation window and click the Object button, then make them all walkable by checking Navigation Static and setting the Navigation Area to Walkable. Make the Obstacle GameObject not walkable by selecting it, clicking Navigation Static, and setting Navigation Area to Not Walkable.

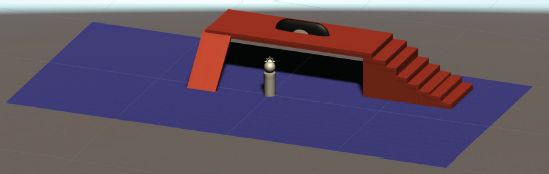

Now follow the same steps that you used before to bake the NavMesh: click the Bake button at the top of the Navigation window to switch to the Bake view, then click the Bake button at the bottom.

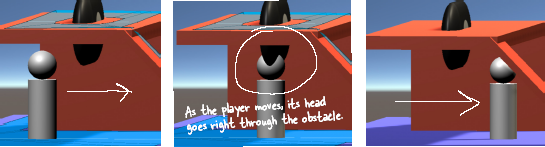

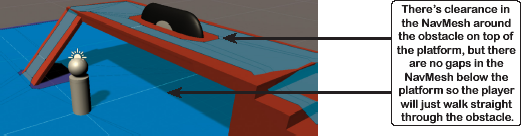

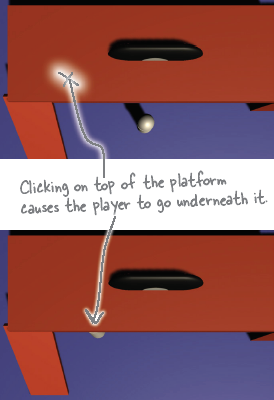

It looks like it worked! The NavMesh now appears on top of the platform, and there’s space around the obstacle. Try running the game. Click on top of the platform and see what happens.

Hmm, hold on. Things aren’t working the way we expected them to. When you click on top of the platform, the player goes under it. And if you look closely at the NavMesh that’s displayed when you’re viewing the Navigation window, you’ll see that it also has space around the stairs and ramp, but doesn’t actually include either of them in the NavMesh. The player has no way to get to the point you clicked on, so the AI gets it as close as it can.

Add a script to move the obstacle up and down

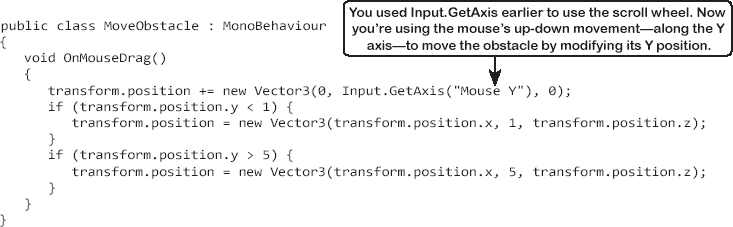

This script uses the OnMouseDrag method. It works just like the OnMouseDown method you used in the last Lab, except that it’s called when the GameObject is dragged.

Note

The first if statement keeps the block from moving below the floor, and the second keeps it from moving too high. Can you figure out how they work?

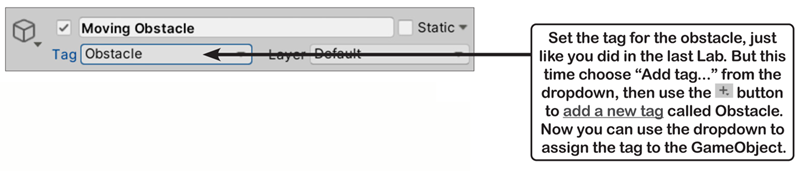

Drag your script onto the Moving Obstacle GameObject and run the game—uh-oh, something’s wrong. You can click and drag the obstacle up and down, but it also moves the player. Fix this by adding a tag to the GameObject.

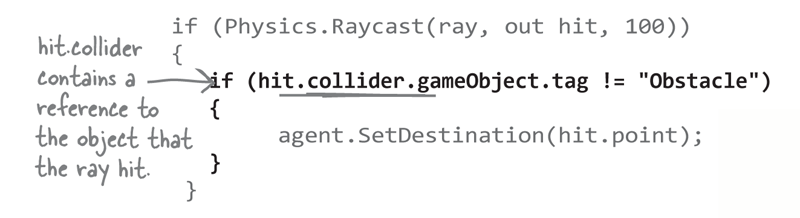

Then modify your MoveToClick script to check for the tag:

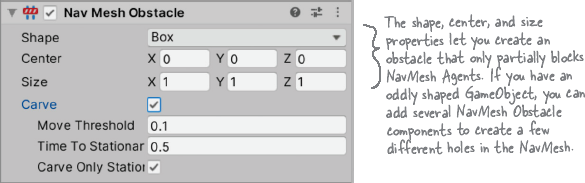

Run your game again. If you click on the obstacle you can drag it up and down, and it stops when it hits the floor or gets too high. Click anywhere else, and the player moves just like before. Now you can experiment with the NavMesh Obstacle options. (This is easier if you reduce the Speed in the Player’s NavMesh Agent.)

Start your game. Click on Moving Obstacle in the Hierarchy window and uncheck the Carve option. Move your player to the top of the ramp, then click at the bottom of the ramp—the player will bump into the obstacle and stop. Drag the obstacle up, and the player will continue moving.

Now check Carve and try the same thing. As you move the obstacle up and down, the player will recalculate its route, taking the long way around to avoid the obstacle if it’s down, and changing course in real time as you move the obstacle.

Get creative!

Can you find ways to improve your game and get practice writing code? Here are some ideas to help you get creative:

Build out the scene—add more ramps, stairs, platforms, and obstacles. Find creative ways to use materials. Search the web for new texture maps. Make it look interesting!

Make the NavMesh Agent move faster when the player holds down the shift key. Search for

KeyCodein the Scripting Reference to find the left/right shift key codes.You used OnMouseDown, Rotate, RotateAround, and Destroy in the last Lab. See if you can use them to create obstacles that rotate or disappear when you click them.

We don’t actually have a game just yet, just a player navigating around a scene. In the next Unity Lab we’ll pick up where this one leaves off, but you don’t have to wait. Can you find a way to turn your program into a timed obstacle course?

You already know enough about Unity to start building interesting games—and that’s a great way to get practice so you can keep getting better as developer.

Note

This is your chance to experiment. Using your creativity is a really effective way to quickly build up your coding skills.