Chapter 4

Local and global, North and South

By 1648, territories in the Holy Roman Empire had been at war for thirty years, and the Spanish and Dutch for eighty years. In that year the Westphalian Treaty was signed. This treaty established a principle that has influenced national and international politics ever since—the principle of sovereignty. In 1648 this involved the right of rulers to determine the religion of their subjects, and by 1918 it had come to embody the broader idea that nation states have a right to determine their own affairs without interference from other states. The principle spread from its European origins and was eventually a driving force behind the decolonization process that freed countries from colonial rule during the second half of the 20th century.

The principle is a powerful and important one for obvious reasons, and it has a special relevance in the context of environmental politics. Environmental problems are famously borderless, and this complicates the principle of national self-determination that is at the heart of international politics. For an increasing number of people in the world (though still a minority) our very lives are increasingly borderless. The components in your laptop come from up to sixteen different countries, your trainers might be made in Vietnam, your tea from Kenya. So complex is the sourcing of materials, the process of putting them together, and shipping and marketing them, that it took Pietra Rivoli years to research The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy. Another way of illustrating the borderless character of much modern production and consumption is through the idea of the ‘ecological footprint’. Each of us has an impact on the Earth in terms of the resources we use and the waste we produce—this is our ecological footprint. The ecological space our footprint occupies is obviously not confined to our immediate surroundings—we ‘borrow’ space from elsewhere. A glance at the contents of your refrigerator or wardrobe will confirm this. The more globalized our lives are, the more ‘smeared’ our footprint is across the planet.

Globalization

In this sense, environmental politics is an international politics—even a global politics. In his book The End of Nature (1989), Bill McKibben argues that what marks out the contemporary world from any previous period of human history is, precisely, the capacity humans have for influencing their environment at a global level. Global warming, he says, is exactly that—global. We have now altered ‘every inch and every hour of the globe’:

If you travel by plane and dog team and snowshoe to the farthest corner of the Arctic and it is a mild summer day, you will not know whether the temperature is what it is ‘supposed’ to be, or whether, thanks to the extra carbon dioxide, you are standing in the equivalent of a heated room.

This is the environmental version of what has come to be called ‘globalization’—the phenomenon which is so especially in tension with the principle of national sovereignty enshrined in the Westphalian Treaty of 1648. It has also led to the suggestion that human impact on the environment is so far-reaching that we have set in train a new geological epoch—the Anthropocene. We will look at this further in Chapter 5.

6. A child recycling e-waste in Guiyu, China: one aspect of globalization.

In a classic definition, David Held talks of globalization as the ‘widening, intensifying, speeding up and growing impact of world-wide interconnectedness’. Obviously this process is not uniform, in terms of either speed or impact; it is not symmetrical. Indian feminist and environmentalist Vandana Shiva argues that the asymmetry of globalization takes a particular form—one in which the global North globalizes while the global South is globalized (see Figure 6):

The construction of the global environment narrows the South’s options while increasing the North’s. Through its global reach, the North exists in the South, but the South exists only within itself, since it has no global reach. Thus the South can only exist locally, while only the North exists globally.

Global warming is a good example of this asymmetry at work, as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. The asymmetry of the global environment

| Country | CO2 emissions per capita (in 2010) |

|---|---|

| United States | 17.5 |

| United Kingdom | 8.0 |

| Australia | 16.8 |

| Canada | 14.7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 16.9 |

| Spain | 5.9 |

| China | 6.2 |

| India | 1.6 |

| Brazil | 2.2 |

| Bangladesh | 0.4 |

| Ethiopia | 0.01 |

Source: Millennium Development Goals indicators (2013) |

|

In Shiva’s terms these figures show that the ‘North exists in the South’ by imposing global warming on the South (represented by India, Brazil, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia in the table) through higher per capita emissions. This is asymmetrical globalization at work, though it is important to recognize how geo-environmental realties can shift over time—China is now a bigger aggregate CO2 polluter than the USA, even though its per capita emissions are lower.

The role of globalization in the environmental crisis is disputed. It would be wrong to say that it has caused environmental problems as they evidently existed before the processes described by Held and Shiva got under way. But it is fair to say that increased rates of investment, trade, and production have accelerated and intensified environmental impacts around the world. Critics of this process argue that it is not just that trade volumes have increased, but that the terms of trade are such that environmental sustainability is not sufficiently taken into account. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is a key player in this regard. The WTO was founded in 1995 as a successor to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) which was signed in 1947. The GATT was designed to reduce trade barriers, and the WTO’s remit is similar. This creates problems around increasingly important environmental issues such as biosecurity. Biosecurity has been described as ‘the attempted management or control of unruly biological matter’, and it is clear how the controls and import restrictions this implies are in tension with the open market and free trade promoted by the WTO. Effective biosecurity is important from the point of view of plant, animal, and human health, and we can see from the Ebola crisis of 2014 what happens when biosecurity breaks down. The tension between free trade and biosecurity is captured in the WTO’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) agreement which states that member states have a right to impose restrictions to preserve plant, animal, or human health, but not where these measures discriminate on the grounds of process and production methods, or impose ‘unnecessary, arbitrary, scientifically unjustifiable or disguised restrictions on trade’.

This is why governing plant and animal health in a neoliberal globalized world is a challenge. For example, there have been two Dutch Elm disease pandemics in the 20th century, and both were caused by the transport of infected timber. The increasingly international horticultural trade has also opened up transmission routes for plant diseases and insect pests. The WTO has a Dispute Settlement Panel where disagreements between governments trying to limit trade and companies resisting those limitations are resolved. It is significant that many of the trade disputes in recent years have been around biosecurity, including the infamous Australia/New Zealand apple dispute. Australia banned the import of New Zealand apples in 1921 on the grounds that they were a source of a bacterial infection called fire blight. In 2007 New Zealand began WTO dispute settlement procedures and the Australian ban on apple imports was overturned. It would be too simplistic to see this as a victory of free trade over environmental considerations since other factors come into play, but it is an example of the tensions between globalized trade and environmental protection.

On the other hand, globalization is also a process that has contributed to raising per capita income across the world, though very unequally and not everywhere. Some argue that this is good for the environment as it produces the wealth required to pay for better environmental protection and technologies. This theory is based on the environmental Kuznets curve, which purports to show that environmental quality decreases in the early stages of a country’s development, but then improves once a certain average income is reached. This suggests that the best way for a country to improve its environmental performance is to get richer. The Kuznets curve (an inverted U-shape) is criticized on the grounds that it tends to hold for some environmental quality indicators, such as clean water and air pollution, but not for others, such as greenhouse gas emissions and the average per capita size of ecological footprints. These criticisms are important to bear in mind when considering Kuznets-based arguments for the possibility of decoupling economic growth and environmental impact (ecological modernization).

International environmental diplomacy and agreements

Whatever one thinks of globalization’s role in undermining environmental protection, or, from an alternative point of view, in creating the conditions for improving it, it has been clear for some time that environmental problems have a transboundary character and therefore require—to some extent—a transboundary approach. On several occasions we have seen how important the early 1970s were to the development of contemporary environmental politics, and in the seminal year of 1972 the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm. This conference ‘discussed common principles to inspire and guide the peoples of the world in the preservation and enhancement of the human environment’, and it marked the beginning of extensive UN involvement in environment and sustainability issues which has lasted to this day. The next major UN-sponsored event was the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987), more commonly known as the Brundtland Commission, named after Gro Harlem Brundtland, the former Prime Minister of Norway who was chosen to chair it. The Brundtland Commission subtly changed the debate’s terms of reference by talking about sustainable development rather than environmental sustainability, thereby signalling a determination to recognize that sustainability of the environment and the development of societies must go hand in hand, without privileging either of them to the detriment of the other. The Brundtland Commission gave us the most commonly used definition of sustainable development: ‘Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.

The most far-reaching UN conference took place in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Its official name was the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), but it is more popularly known as the Rio Summit. It was far-reaching because it set in train three pieces of work, the implications of which are still with us today. The first was the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), in which parties agreed to conserve diversity, use resources sustainably, and share the benefits of diversity fairly. The CBD picks up the Brundtland sustainable development theme, containing the idea that genetic resources should be developed—but sustainably—for the benefit of present and future generations. The second was called Agenda 21, and particularly Chapter 11 of Agenda 21, which focused on the role of local authorities in embedding sustainable development. Local Agenda 21, as it came to be known, embodies the well-known mantra ‘think global, act local’, and it enjoined local actors across the world—elected officials, citizens, and businesses—to develop plans for sustainable development at the local level. Take up was inevitably patchy, and over three-quarters of the activity took place in Europe—particularly in the UK and Sweden—but where the practice took root, a legacy which legitimized local participation was created which citizens and other local actors continue to access.

The third was the most far-reaching Convention of all—the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This treaty set in train the climate change negotiations which are still ongoing. Its aim was—and is—to ‘stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’. No specific limits or mechanisms were set at this point, but the signatories agreed to meet every year at a Conferences of the Parties (COP) to develop legally binding obligations. The best-known COP was the one that took place in Kyoto in 1997, and which gave rise to the Kyoto Protocol.

We will be discussing the climate change negotiations in more detail shortly in the context of an analysis of the factors that both help and hinder international environmental agreements. Any such agreement needs to overcome a series of challenges. We have already mentioned the key issue of national sovereignty: any international agreement is likely to involve some compromise as far as perceived national interest is concerned. Second, most environmental issues involve science and scientific data. While we might think that this would make for a solid bedrock on which to base agreements, the opposite tends to be the case: either the data or the conclusions drawn from them are a source of constant dispute. Third, divisions among ‘developed’ nations as to the best way forward are common, and this is compounded by what has until recently been an apparently insurmountable faultline between the global North and the global South. This faultline represents the tension between environmental protection on the one hand and development on the other. The global South believes that equity is a key issue in multilateral environmental negotiations, for two reasons. First, they argue that the global North has caused the lion’s share of global environmental problems, and has benefited from doing so. This is why the global North should bear the brunt of the costs of protection. Second, the global South should not have to forgo development for the sake of environmental protection. Development has brought tremendous benefits to the global North, and it would be unfair to deny those benefits to the global South, especially in respect of a problem (environmental degradation) for which the global North is primarily responsible.

The fourth challenge to reaching meaningful and actionable multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) is the multiplicity of actors in play, and in particular the capacity some have for influencing democratically elected governments. Corporations and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) are important players in negotiations, but the power of the former far outweighs the latter, and corporations have the capacity to make or break negotiations, as we shall see shortly in the context of the Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer. The final obstacle is the growth imperative which constitutes the context for all environmental negotiations. The idea of a ‘one planet economy’ has very little traction at the international level; and from the point of view of the political ecologist who believes that there are limits to growth, this amounts to fighting with one hand tied behind one’s back. Despite these obstacles, multilateral environmental agreements are possible, and we shall shortly be comparing and contrasting two cases—the ozone layer and climate change—to help analyse the factors and conditions that make for successful agreements. Some of the key MEAs across a range of environmental issue areas are summarized in Table 3.

What makes for a successful international environmental agreement, and what gets in the way of success? Forty years of trial and error allow us to draw some conclusions, and attention is often drawn to two contrasting sets of negotiations with a view to outlining the factors that make success more or less likely. The negotiations in question are those around the protection of the ozone layer, on the one hand, and those around climate change, on the other. Both of these looked very difficult—even intractable—at the outset, but one resulted in a lasting and generally well-observed agreement, while the other is the subject of endless disputes that have yet to result in an agreement that satisfies both the science as well as the potential parties to the agreement. We will look at these in turn.

Table 3. Some key multilateral environmental agreements

| Issue area | Name of Convention or Treaty | Date and place |

|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere | Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution | Geneva, 1979 |

| Marine living resources | Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources | Canberra, 1980 |

| Marine environment | UN Convention on the Law of the Sea | Montego Bay, 1982 |

| Nature conservation | Convention on Biological Diversity | Nairobi, 1992 |

| Nuclear safety | Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty | 1996 |

| Hazardous substances | Minamata Convention on Mercury | Minamata, 2013 |

Ozone diplomacy—a relative success story

The ozone layer is essential for life on Earth as we know it. It is a layer in the stratosphere, between 19 and 30 kilometres above the Earth’s surface, that contains high concentrations of ozone relative to the rest of the atmosphere and absorbs most of the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) radiation. UV radiation causes us to tan, but an excess can increase the chances of skin cancer and eye damage. It can also harm plants and animals and, as UV rays can penetrate water, they are especially dangerous for plankton, at the base of the marine food chain. In May 1985, an article was published in Nature announcing an annual depletion of the ozone layer above the Antarctic—between 1955 and 1995 the ozone concentration at springtime declined by about two-thirds. In 1974 it had been suggested that ozone concentrations could be adversely affected by man-made chemicals containing chlorine, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), but also compounds containing bromine, other related halogen compounds, and nitrogen oxides (NOx). CFCs are used in refrigeration systems, air conditioners, aerosols, solvents, and some types of packaging. Nitrogen oxides are a by-product of combustion, for example from car or aircraft engines. The evidence that these chemicals were indeed causing the annual depletion in the ozone layer piled up, and in 1988 the science-based Ozone Trends Panel confirmed the connection between CFCs and ozone depletion. By this point, one key ingredient for a successful international agreement was in place: consensus on the science. Even ahead of this scientific confirmation, twenty nations signed the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer in 1985, which produced no targets for limiting CFC production but did provide a framework for co-operation on the issue.

CFCs were invented in the 1920s, and by the time the danger they represented was fully understood, they had become a significant player in modern industrial economies. This meant that large chemical firms, such as ICI and Dupont, stood to lose millions of dollars from a ban on CFCs unless substitutes could be found. To begin with these firms claimed that the science behind the ozone depletion theory was faulty, but then in 1986 Dupont broke with other producers by announcing that it would back negotiations to limit CFC production. Two possible reasons have been given for this. First, the US government had banned CFCs such as Freon in aerosol cans, while a Dupont patent on Freon had in any case expired in 1979. This combination of adverse regulation and a decline in competitive advantage in the market place made continued investment in CFCs seem less attractive. Second, Dupont recognized that competitive advantage could be regained by developing substitute chemicals—this would give it first mover advantage. This led to a race with a number of other companies such as ICI to develop substitutes for CFCs which would do the same job without depleting the ozone layer. As a result, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are increasingly used as substitutes. Corporations thus played a critical role in the development of an ozone agreement—without their support, neither a successful accord nor its implementation would have been as likely.

Another key element in the development of the ozone regime was the negotiating states themselves. In 1977, the so-called Toronto Group, comprising Norway, Finland, Sweden, the USA, and Canada, unilaterally banned non-essential aerosol use (asthma inhalers, for example, were exempted). European Community states, under pressure from producers responsible for up to half of world CFC production at the time, resisted any call for action until West Germany broke with the European consensus. By this point, the negotiating states, the science, and the corporations were all more or less aligned, and the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was signed in 1987. Since then, CFC concentrations have levelled out or decreased, but the sting in the tail is that their replacements, hydrofluorocarbons, contribute to global warming.

The treaty was the first universally ratified treaty in United Nations history, and this meant that an additional hurdle had to be overcome—persuading developing countries to sign up. Ozone depletion had been caused principally by the already industrialized countries, though its effects were felt by everyone. Likewise, CFCs had enabled industrialized countries to take advantage of refrigeration and other technologies in competitive markets. Why should developing countries bear the cost of solving a problem they hadn’t caused? In 1990 a technology transfer fund was set up to help developing countries transition to ozone-safe production. This helped to establish the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’—i.e., that all states have a responsibility for dealing with global environmental problems, but that some states have more of a responsibility than others. Finally, signatories to the Protocol agreed to build sanctions into the treaty, designed to punish countries which might be tempted to leave it or break it.

This brief analysis of the Montreal Protocol helps us to identify the key features of a successful multilateral environmental agreement: a consensus on the science; a key state or states (in this case West Germany) tipping the balance in favour of agreement by disengaging from the laggards and joining the leaders; a ready alternative to the phenomenon, situation, or entity that is causing the problem; a resolution of any equity issues that might be raised by pursuing this alternative; and sanctions for transgressors.

Climate change diplomacy—a relative failure

We can helpfully contrast the relatively successful ozone story with the much more intractable issue of global warming, or climate change. Why has this proved so much more difficult a nut to crack? There are similar factors in play: scientific evidence, national sovereignty, divisions between countries in the global North, divisions between the global North and the global South, and the power of large corporations. But while it was possible to overcome the problems arising from these factors in the ozone case, it has proved much more difficult to do so with climate change. Before discussing why, we need to see what global warming is, the state of the science surrounding it, and the implications of global warming for human and other life.

Global warming—or climate change—is a result of the ‘greenhouse effect’. (In what follows I will be using the terms ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ indistinguishably. Some have suggested that ‘climate change’ is too neutral a term in that it implies the possibility of temperatures going up and down—as they have done throughout the planet’s history—and therefore plays into the hands of those who would say that any current change in average global temperatures is part of natural variation. The term ‘global warming’ makes it clear that temperatures are rising, and, given that the temperature rise coincides with the increased burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution, the conclusion that human activity is the cause of the rise.) Up to a point the greenhouse effect makes life on Earth possible—certain gases such as carbon dioxide, water vapour, methane, and nitrous oxide absorb some of the sun’s radiation as it is reflected back off the Earth’s surface, trapping heat in the atmosphere. Without this effect, the Earth’s average surface temperature would be over 30°C lower than it is at present: roughly −18°C rather than 15°C. This wouldn’t make life impossible, but it would make it very difficult. The problem is that the scientific evidence amassed over several decades strongly suggests that the balance is being upset by human activity, which is increasing the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, leading to a rise in average temperature at the Earth’s surface. This is anthropogenic climate change—i.e., climate change which is caused by human beings—as distinct from any ‘natural’ greenhouse effect.

The body that co-ordinates the scientific evidence regarding climate change is called the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), founded in 1988 under the auspices of the United Nations. The IPCC has published five assessment reports (1990, 1992, 1995, 2001, and 2014) reviewing the latest climate science. IPCC reports are broadly accepted by governments around the world and the evidence they gather provides the basis for the climate change negotiations we will be discussing shortly. There is resistance to the idea of anthropogenic climate change, though, in the form of ‘climate scepticism’. Climate sceptics lodge three doubts: first, they query the reasons for the increase in temperature, and in particular the way in which temperature rise is supposed to follow increases in greenhouse gases concentrations; second, whether the temperature rise exceeds normal variation; and third, whether human activity is the principal cause of the observed warming. A related objection is that even if anthropogenic climate change exists, overall human welfare would be more greatly increased if, instead of spending money on mitigating climate change, we spent it on finding a vaccination for malaria or providing clean water for the billions of people who don’t have it. This argument is most powerfully and controversially put in Bjørn Lomborg’s The Skeptical Environmentalist.

In response to the climate sceptics, 97 per cent of scientists say that it is very likely that human activity is causing global warming, and the main conclusions of the IPPC’s latest Summary for Policymakers are collected in Box 1. But while the science of climate change might be settled, the politics of the science certainly is not. Climate scepticism tends to follow political cleavages, with scepticism more common on the right than the left. It is particularly prevalent in the USA, where Republicans have been active in promoting scepticism, though there are also loud sceptical voices in the UK and Australia.

Box 1 IPCC—selected conclusions from the ‘Summary for Policymakers’

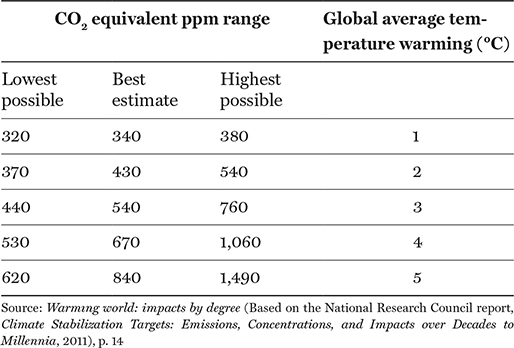

Even though the phenomenon of anthropogenic climate change is now accepted by the vast majority of scientists, there is still uncertainty around two key questions: by how much will the Earth’s average surface temperature rise; and what will the consequences of this rise be? Given the uncertainties around these questions, the IPCC and others have developed scenarios to illustrate the possibilities. The answer to the first question is closely linked to the concentrations of CO2 equivalent gases in the atmosphere (‘CO2 equivalent’ is a way of making the calculations easier by translating the effect of each of the greenhouse gases into CO2 terms). The Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison, working out of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in San Francisco, has devised the scenarios laid out in Table 4.

Table 4. Possible global warming scenarios

We can put the CO2 equivalent figures into perspective by seeing that the pre-industrial parts per million (ppm) level was 280ppm, and the highest it has ever been in the last 800,000 years is 300ppm. In March 2015, the concentration was at 401.52ppm (based on data from the Mauna Loa observatory, Hawaii), so we are already in the range at which we can expect 2°C of warming.

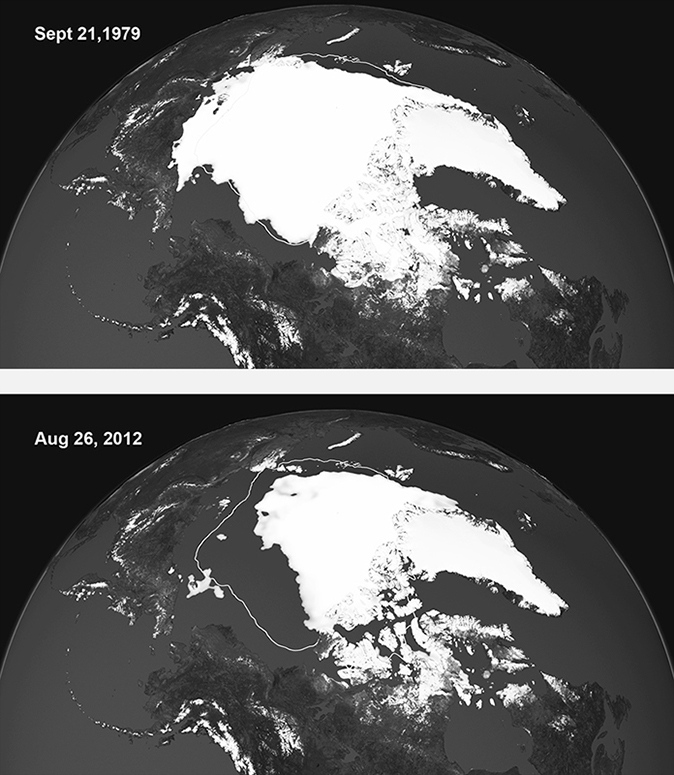

The other key figure in the table is the one in the right-hand column—the average temperature rise we can expect given certain CO2 equivalent concentrations. But what do these potential rises mean in terms of their effect on human and other life? Predictions are hard to make, in part because rises in temperature will not be uniform across the world: land warms quicker than the oceans, and high latitudes (particularly the Arctic) will experience greater temperature increases (see Figure 7). Bearing this in mind, in 2007 (updated 2013) the UK’s Meteorological Office assessed the likely impact of a 4°C rise across a range of issue areas such as sea level rise, health, agriculture, water availability, and the marine environment. Among other effects, the Met Office predicts a 60 per cent chance of irreversible decline of the Greenland ice sheet, bringing about a 7-metre sea level rise; hottest days of the year could be as much as 8°C hotter in Europe and 10–12°C hotter in Eastern North America; ocean acidification will affect fisheries and coral reefs and those whose livelihoods depend on them; rice yields will decrease by up to 30 per cent in China, India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia; and there will be an increase in diarrhoea, dengue fever, malaria, and malnutrition, as well as the health-related impacts of weather effects such as flooding and drought.

7. Decline in summer ice in the Arctic between 1979 and 2012.

All this gives us a picture of the latest climate science evidence and its implications. This evidence suggests that we are on the way to dangerous levels of global warming, and that greenhouse gas emissions need to be reduced. From an environmental politics point of view, the challenge is how to reduce these emissions given an international political system comprising sovereign nation states, some disagreement over the science, divisions among ‘developed’ countries, divisions between North and South, and the interests of the fossil fuel lobby in keeping the present system going.

Climate change first made its entry into the international arena in treaty terms at the Rio Summit in 1992, with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). By this time, a degree of scientific consensus had been achieved through the first IPCC report in 1990—what was missing was a policy response from governments. The UNFCCC contained no binding agreements, except on reporting, but governments did commit to a succession of Conferences of the Parties (COPs) at which they would set targets and make commitments. The best known of these is COP-3—the Kyoto Protocol of 1997—where a legally binding commitment by developed countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5 per cent of 1990 levels by 2012 was agreed. Kyoto set important precedents by distinguishing between Annex 1 (developed) and non-Annex 1 (developing) countries, placing the onus to act on Annex 1 countries, and by developing the principle of common yet differentiated responsibility. It also established three market-based mechanisms for reducing emissions: a trading regime allowing Annex 1 countries to buy and sell emission credits among themselves; a Joint Implementation method by which Annex 1 countries could implement carbon savings in other Annex 1 countries in exchange for emission credits; and a Clean Development Mechanism whereby Annex 1 countries get emission credits by funding carbon-saving projects in developing countries. These ‘flexible mechanisms’ seem sensible in that the point is to make reductions overall rather than make them in any particular place. But they have been criticized: (a) for allowing countries off the hook by displacing responsibility; (b) because it is hard to measure the reductions achieved by these mechanisms; and (c) because their success depends on an effectively enforced global cap, which has proved difficult to establish and achieve. They also do not take into account the ‘export’ of emissions—up to one-third in the case of the UK—caused by the consumption of goods and services produced elsewhere.

In terms of dealing with climate change, Kyoto had—and has—its flaws. Climate science tells us that the agreed reductions are not sufficient to keep us below 2°C, the flexible mechanisms just described are not as effective as regulation and sanctions would be, and the Annex 1/non-Annex 1 split has been a source of constant aggravation. Countries of the global North, and especially the USA, regarded it as unfair to exempt industrializing countries from emission reductions, and in 2001 the USA renounced the Kyoto Protocol on the grounds that—as President George Bush (senior) put it—it was a threat to the American way of life. As the Protocol required ratification by fifty-five countries which accounted for 55 percent of the emissions of Annex 1 countries before coming into force, America’s backtracking resulted in frenetic manoeuvring as governments—particularly Russia—sought to extract concessions in exchange for their signatures. The Protocol finally came into force in February 2005, a compromise agreement that had negotiated the rocky shoals of scientific uncertainty, national self-interest, and demands for global equity.

Subsequent climate negotiations have found it difficult to overcome the tensions that have been evident since the UNFCCC in 1992. COP-15 in Copenhagen (2009) was billed as a replacement for Kyoto, but it foundered on disagreement over whether industrializing countries should take independent emission reduction measures. Lumumba Di-Aping, chief negotiator for the G77 group of 130 developing countries, said the deal represented ‘the lowest level of ambition you can imagine. It’s nothing short of climate change scepticism in action. It locks countries into a cycle of poverty for ever’, while John Sauven, executive director of Greenpeace UK, said: ‘The city of Copenhagen is a crime scene tonight, with the guilty men and women fleeing to the airport’. COP-20 in Lima (December 2014) looked as though it was heading in the same direction until the very last moment when the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ principle, which had given industrializing countries a justification for not reducing emissions, had a rider added to it: ‘in light of different national circumstances’. No flesh was put on the bones, though, and at the time of writing all eyes are on Paris, where in December 2015 the COP-21 objective will be to ‘achieve a legally binding and universal agreement on climate, from all the nations of the world’.

Of the five factors which led to success in the ozone/CFCs negotiations, only one—scientific consensus—is present in the global warming context, and even the science is under constant (if minority) attack from climate sceptics. There has been little agreement among ‘developed’ states as to objectives or mechanisms, and the key state—the USA—has been a reluctant fellow-traveller in negotiations throughout (though under President Obama there are signs of a significant softening of the USA’s position). The global equity problem has not been solved, and there is still debate over how to measure emissions—per capita or per country. China has the most emissions measured by country, but it is some way behind the USA and the European Union, for example, when measured on a per capita basis. Finally, there is no ready substitute for fossil fuels, as there was for CFCs, and there is no sanctionable agreement to prevent states free-riding. In other words, even taking account of successful multilateral negotiations such as the Montreal Protocol, there is little evidence of the development of an internationalist cosmopolitanism to replace the state-centric inclinations embodied in the Westphalian Treaty with which we began this chapter. Multilateral environmental agreements are still more a demonstration of sovereignty than an abandoning of it.

Meanwhile, global emissions continue to increase—by 2.3 percent on 2013 levels, according to the Global Carbon Project (GCP). That is 61 percent higher than in the Kyoto reference year of 1990. The GCP reports that,

Current trajectories of fossil fuel emissions are tracking some of the most carbon intensive emission scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The current trajectory is tracking baseline scenarios in the latest family of IPCC scenarios that takes the planet’s average temperature to about 3.2°C to 5.4°C above pre-industrial times by 2100.

The same report suggests that we are on course to use up our quota of carbon emissions, consistent with keeping temperature rise to 2°C or less, within thirty years, and that we should be aiming to keep about half of our fossil fuel reserves in the ground, consistent with the same objective. Against this background, the challenge faced by policy-makers in Paris in 2015, and beyond, is enormous.

From the global to the local

While international environmental problems like ozone depletion and global warming seem obviously to require international-level policy, this is not the only scale at which they can be confronted. Indeed, frustration at the slow progress of climate change talks at the national and international level has led to alternative approaches at sub-national level—particularly cities. Over half the world’s population lives in cities—and that figure is set to grow—so it makes sense to focus on this scale of policy development and implementation. In 2005, the then Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, invited representatives from eighteen ‘megacities’ (i.e., cities with a population in excess of ten million inhabitants) to a meeting to discuss measures for reducing greenhouse gases. By 2006, the network had grown to forty cities and the term ‘C40Cities’ was coined as a name for the group—there are now seventy affiliated cities. C40Cities climate change mitigation action is driven by the mayors of the cities, who undertake to identify measures in policy areas where they have political competence, such as water, energy, finance and development, measurement and planning, solid waste management, and transport. At this scale, action can be taken irrespective of the success or failure of talks at the international level.

Another initiative, rooted more in the formal machinery of the United Nations, is the Cities for Climate Protection (CCP) programme, founded in 1990 by the International Union of Local Authorities and the United Nations Environment Programme. The CCP programme comprises over 650 municipalities from around thirty countries, and action is taken—as in the C40Cities example—where local government has relevant competencies such as land-use planning, traffic, and housing. Both C40Cities and CCP are examples of ‘non-state transnational climate action’, where entities at the sub-state level work beneath and across national boundaries to achieve climate change objectives.

More broadly, we have already commented on the United Nations’ recognition of the importance of the local level for the implementation of policies for sustainable development, through Local Agenda 21, developed at the Rio Summit of 1992:

Because so many of the problems and solutions being addressed by Agenda 21 have their roots in local activities, the participation and co-operation of local authorities will be a determining factor in fulfilling its objectives … As the level of governance closest to the people, they play a vital role in educating, mobilizing and responding to the public to promote sustainable development.

The success of Local Agenda 21 was inevitably patchy, depending as it did on the differing competences of local government across a wide variety of countries with different political systems. In some places it served to energize a relatively dormant local government (e.g., the UK), while in others it was enthusiastically taken up in countries with a tradition of strong local government (e.g., Sweden).

Underpinning these relatively formal initiatives, it is important to see that the local scale has always been important in environmental politics. The link between the local and global is captured in the well-worn phrase ‘‘think global, act local’’, which lends primacy of action to the local level in the belief that myriad threads of sustainable action at that level will amount to a tapestry of sustainable development at the global level. For this reason, environmental politics has always had an enduring decentralist character, and there is a creative tension between those who argue that environmental politics should be wholly local, and those who feel that the global (or at least international) character of environmental problems means that they need a response at the global level.

The localists point out, in response, that these global problems are a result of dysfunctionalities at the local level. They argue, for example, that the scalar gap between production and consumption has grown too wide to be sustainable, and that there should be more local production for local use. This gives rise to the idea of the ‘prosumer’ (a term coined by Alvin Toffler in Future Shock in 1973)—the producer who consumes what she or he produces. A good example of this in action is the allotment system in the UK, where citizens grow their own food for their own (or their friends’) consumption. Allotment ‘prosumers’ are a growing force, and it was estimated in 2011 that there was a waiting list of nearly 100,000 would-be local food-growers in the UK. Another argument in favour of more localized politics is that it helps to generate the disposition of care for the land which is a core feature of environmental politics—‘land’ understood in the general sense of ‘that which sustains and surrounds us’. From this point of view, care for the global environment piggybacks on care for the local environment—we are less likely to exercise the former if we don’t have the opportunity to ‘practise’ the latter.

The local level is also crucial to environmental politics because this is where its implications are felt most viscerally and its battles are fought most keenly. Far from the air-conditioned meeting rooms of UN environment conferences and the lobbies of five-star hotels adorned with fountains and plush sofas frequented by their delegates, we find lives blighted by our failure to implement an effective politics for sustainability—or, occasionally, lives enhanced by our success in doing so. These battles are often fought over LULUs—Locally Unwanted Land Uses—and we find them all over the world. The battles are fierce because they affect people’s immediate, daily lives—often their very livelihoods. This, after all, is where most people’s concerns lie, most of the time. The issues with which much of this chapter has been taken up, such as biodiversity, ozone depletion, and global warming can seem far away in space and time, and are therefore crowded out by more immediate concerns. Environmental issues have a greater ‘felt’ relevance if they affect the family, neighbourhood, or city over the next few months or years. It is worth pointing out, though, that even the apparently remote issues of biodiversity, ozone depletion, and global warming are more immediate for some people. Examples are the indigenous inhabitants of rainforests who depend on a relatively undisturbed habitat for their livelihood, or the 400,000 Maldive islanders threatened by a climate change-induced sea level rise that could see parts of their nation underwater within a hundred years. For these people, climate change is here and now, not far away in some ill-defined future. In October 2009, President Mohamed Nasheed, then Maldives President, held a cabinet meeting underwater to draw the world’s attention to his people’s plight, and to urge effective action at the Copenhagen climate change summit in December that year.

LULU disputes drive some of the most contentious examples of environmental politics in action. They involve some change in local land use which is perceived as harmful to sectors of the local population. An example drawn from Europe is the siting of windfarms, to which some local people object because they spoil the view, make too much noise, or kill birds. Note that these are objections of a different type to the more generic ones regarding cost or efficiency. They are rooted in the effect the wind turbines have on the daily lives of the objectors, rather than in the more abstract reservations that anyone might have about wind turbines—even those who live nowhere near the windfarm itself. LULU disputes often come trailing another acronym—‘nimby’, or ‘Not In My Backyard’. ‘Nimby’ is a pejorative term, implying as it does that the development being objected to would be acceptable if it was happening somewhere else. Local environmental disagreements can often bring people and organizations with an environmental or sustainability brief into conflict with one another. So while Friends of the Earth (UK) supports the development of onshore wind energy, the Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE) takes a much more cautious view: ‘While wind energy can make an important contribution to tackling climate change, CPRE believes this should not come at the expense of the beauty, character and tranquillity of rural England’.

Local livelihoods, the environment, and social struggle

Local environmental disputes are often about much more than ‘only’ the environment, and involve issues around democracy, participation, and justice too. One example is the long-running conflict over a number of large dam projects on the Narmada River in India. Protest has focused on the largest of these, the Sardar Sarovar Dam, in Gujarat. The dam has been the subject of a series of proposals over the past thirty years to increase its height, thereby increasing the size of the reservoir, providing water for homes and industry, irrigation, and hydroelectric power. Significantly, the opposition group ‘Friends of River Narmada’ refers to the dam’s construction as ‘one of the most important social issues in contemporary India’, rather than as an environmental issue. This is because much of the resistance to the project is rooted in a consistent lack of consultation of those affected by the plans, inadequate rehabilitation and compensation, and the way in which the plans inequitably affect the poorest and most vulnerable communities along the river. Friends of River Narmada sum up the social and environmental consequences of the development of large dams as follows: ‘they have had an extremely devastating effect on the riverine ecosystem and have rendered destitute large numbers of people (whose entire sustenance and modes of living are centered around the river)’. In cases like this, defending the integrity of ecosystems is not a matter of honouring some abstract principle, but of resisting an attack on livelihoods in the here and now.

It is striking how many of these environment-related local protests in defence of livelihoods are led by women. One of the key Narmada opposition groups, for example, is Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), whose leading spokesperson is Medha Patkar. Patkar abandoned her PhD at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences to campaign full-time, and has carried out a number of hunger strikes in protest at land grabs, house demolitions, and dam development. She was awarded the Right Livelihood Prize in honour of her social activism in 1991. This leadership by women is striking, but perhaps, on reflection, not surprising. After all it is women who are in the forefront of carrying out, and protecting the conditions for, the reproduction of life, and are therefore most immediately aware of threats to it. Nor are these local, livelihood-orientated actions confined to the global South. In recent years a powerful ‘environmental justice’ movement has grown in the global North, aimed at securing a fair share of environmental resources and political recognition for the poor, the vulnerable, and the disadvantaged.

One of the most famous environmental justice actions involved another woman, Lois Gibbs, who began to notice a pattern of childhood illnesses and birth defects in the local population of Love Canal, a Niagara Falls neighbourhood (New York) in the late 1970s (see Figure 8). Gibbs led her neighbours in a battle with local, state, and federal authorities, and with business stakeholders who had much to lose if findings went against them. It turned out that the houses and schools had been built on land in which 22,000 tonnes of toxic waste had been buried by Hooker Chemicals, and after years of campaigning over 800 families were rehoused and compensated. This is just one instance of the environmental injustice which has given rise to what we saw Joan Martínez-Alier, in Chapter 2, refer to as an ‘environmentalism of the poor’. Poor communities get more than their fair share of landfill sites and environmental disasters disproportionately affect the vulnerable. Hurricane Katrina, which struck the Florida coast in 2005 and devastated New Orleans, affected poor people more than wealthier ones, not because the disaster was any worse in the poorer suburbs than in the richer ones, but because the poor were less well equipped to deal with it. This is a result of a lack of political resources as well as material ones—the lack of a capacity to be heard in the political arena. From this point of view, environmental justice is as much about political recognition as it is about fair shares in environmental resources.

8. Love Canal: a totemic campaign for environmental justice.

The title of this chapter—‘Local and global, North and South’—invites us to think of the environmental politics of the ‘North’ as global (biodiversity, ozone depletion, global warming), and the environmental politics of the ‘South’ as local (the defence of livelihoods). Reflections on environmental justice strongly suggest, though, that it might be more productive to think in terms of interpenetration: the global North is present in pockets of the global South, and the global South is present in the global North. This helps us to see that the riverside dwellers of the Narmada River have far more in common with environmental justice and environmental racism activists in North America than they do with India’s burgeoning middle-class. It also helps us to see that environmental politics, for all its ‘newness’, is intimately bound up with a ‘traditional’ politics of the demand for voice, recognition, and justice.