10

BLOOD IN THE LANEWAY

‘They say all the world loves a lover – apply that saying to murder and you have an even more infallible truth.’

– Agatha Christie, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930)

As Mollie Dean passed 5 Addison Street at around 12.40 a.m., her assailant came from behind and fractured her skull above the right ear with what was probably a tyre iron; then, as she fell, he hit her again, cracking and exposing the bone above her left eyebrow; her bloodied hair brushed the picket fence. Whether he was the trailing figure, or had lain in wait in the house’s recessed gate, the killer made the most of his opportunity; he undertook the rest of his task with similar deliberation, dragging Mollie’s disabled figure by the ankles to the west side of the street, leaving marks in the dust, and down a diagonal laneway – the bluestone laneway behind the home of Mollie’s uncle Daniel and aunt Emily, by then long abed. Even today it is a dark lane, and about 6 metres in, to the right, a brick wall forms a prow that obscures an old garage door and a patch of concrete from street view.

The hail of blows was furious; they also formed part of a methodical subjection. The killer tried using Mollie’s underskirt to secure her hands, and one of her dark stockings, tied in three strong knots, to attempt a strangulation.* He tore at her clothing, leaving a profusion of scratches and abrasions. Then, in a macabre apery of the sex act, he plunged his tyre iron or equivalent into her vagina, inflicting a superficial internal tear. This took time, but he must have felt he had it – until, perhaps, he was disturbed, for he left his victim just alive. Chances are he moved off down the laneway, emerging in Milton Street, from where it was only five minutes on foot to the canal – useful for the disposal of a murder weapon.

At about 12.55 a.m., Beatrice Owen of 5 Addison Street was awoken by groaning. Her mother, Isabella, thought it might be local cats; her brother Fred dismissed it as a dream. But from the verandah of the family’s bungalow, the human origins of the sounds across the road grew more apparent, even through a screen of cypress trees. Going to the gate, Fred spied the belongings on the pavement. The moans were from the laneway opposite. He threw on clothes and dashed for South St Kilda Post Office to call the police from its phone box. One of Victoria’s half-dozen radio-equipped patrol cars, cruising near Luna Park, was directed to the address, and pulled up just before 1.30 a.m. And as Constable Alfred Guider followed the bloody drag marks across the road and down the laneway, his eyes made out a shadowy supine form.

Mollie Dean lay prone on the concrete, legs spread-eagled, dress and chemise pulled up to expose her breasts, bleeding from her head and vaginal wounds, and exhaling further blood with every insensible noise. She was clearly in urgent medical need. Having summoned the civil ambulance, Guider drove to 26 Broadway, surgery of Arthur Crowley, the local GP; while the doctor hastily dressed, the constable also knocked up his near neighbour Percy Lambell, a detective in Russell Street’s Criminal Investigation Branch, who lived at 1 Broadway. In the interim, Guider’s colleague had draped Mollie’s coat over her; she had fallen ominously silent.

When he arrived just ahead of the ambulance at 2 a.m., Lambell examined items from the victim’s handbag. Purse; powder puff; clippings about rooms to let; geography papers to mark; letters pending reply. One of these, from Betty Davies, which had contained the tickets to Pygmalion, was addressed to ‘Mary Dean’ at 86 Milton Street, Elwood. Once Mollie had commenced her journey to the Alfred Hospital, the detective rounded the corner in search of the address. The house was dark. A car was parked outside beneath a covering. A dog barked at Lambell’s knock.

Detective Jeremiah O’Keeffe: ‘Does any man visit this house?’

Ethel Dean said later that scrabbling at the gate had disturbed her at about 1.15 a.m., and that she had lain awake since, expecting Mollie any tick of the clock. The policeman surprised her – and also did not, for she had, she would claim, always worried about her daughter’s hours. ‘My name is Senior Detective Lambell,’ said the policeman. ‘Is there a girl named Mary Dean who resides here?’ Ethel said yes.

‘Is her father in?’ Lambell asked.

‘No,’ said Ethel. ‘He is dead.’

‘Well, your daughter has met with an accident in Addison Street and we want you to come to the Alfred Hospital,’ Lambell explained. ‘Does anyone else live here with you?’

‘Only my son,’ Ethel answered.

‘Where has your daughter been tonight?’

The reply was edged with iciness: ‘I do not know. She has not been home since Wednesday morning when she left for school. Go and ask Percy Leason or Fritz Hart. They very likely will be able to tell you. I know nothing about her doings.’

Lambell asked if the car outside, covered by a carpet, belonged to Ethel’s son – the idea of a woman of Ethel’s age driving being clearly absurd. When she reported that it belonged ‘to a man who lives up the street’, Lambell offered her transportation to the Alfred. Ethel walked down the passage to the back verandah where Ralph slept and roused him. By the time the patrol car arrived, her mood had deteriorated: she was, said Lambell, ‘very aggressive’, insisting that everyone squeeze up to accommodate Ralph, and rummaging in a bag containing Mollie’s effects. Advised that this was evidence, she asked crossly: ‘Well, what have you done to find out who did it?’ Lambell explained patiently that the vicinity was being searched. He noted that Ethel had moved unconsciously beyond her information that an ‘accident’ had befallen her daughter, that she was assuming an offence and an offender.

Mollie was admitted to Ward 7 of the Alfred ‘unconscious and extremely shocked’. Her clothing was removed, her head shaved, the stocking round her neck cut away. Her eyes still reacted to light, but she was bleeding from multiple wounds, and the extent of her head injuries was shocking: Truth, ever picturesque, would liken the state of Mollie’s skull to ‘an eggshell when it is crushed by a spoon’. Her breathing was stertorous, a broken bone in her trachea having caused one of her lungs to deflate. Her face was bruised and swollen, her pulse thready, her blood pressure weakening. It astonished medical staff she had survived at all. She should be dead already. They monitored her fight for life as best they could.

When she and Ralph arrived, Ethel’s condition was also closely monitored. The duty doctor and night sister noted that Mollie’s mother never asked what had happened to her daughter, or to see her, remaining in the visitors’ room. She asked the latter only whether Mollie was ‘disfigured at all’. Her concerns were allayed. Otherwise, attempts to involve her in conversation elicited a jumble of impressions. ‘I have not seen her [Mollie] since Wednesday morning, but I believe she was with friends she has stayed with before,’ Ethel complained to the sister. ‘I do not know where she was. I have been worried about her for some weeks. She made friends with people I don’t know and she wanted to go and live with them, but I told her I would always prefer her to come home and sleep.’ Even when Ethel was informed of Mollie’s death just after 4 a.m., she asked nothing about its cause.

People in extremity often behave unpredictably. They can become hysterical, operate mechanically, grow garrulous, subside into silence. Ethel’s instincts were self-protective. ‘Oh, those dreadful men,’ she said to the sister at sight of the police. ‘I will be asked all sorts of questions.’ Yet she still remembered, when the police deposited them at home, to tell Ralph to pull the cover from Adam Graham’s car. Though still unaware of the vehicle’s ownership, Lambell noticed this when he returned to the crime scene just before 6 a.m. When he and his colleague Detective Jeremiah O’Keeffe knocked on the door of 86 Milton Street later that morning, it was on their list.

Ethel explained that she had not seen Mollie since Wednesday morning, and had no idea where her daughter had spent the intervening period. ‘She has been leading a bohemian life lately with an artist crowd and I know nothing about her doings,’ Ethel said. ‘But if you see Mr Skipper of the Bulletin office or Percy Leason they may be able to tell you.’

‘Does any man visit this house to see Mollie?’ O’Keeffe asked.

‘No,’ said Ethel.

‘Who took the covering off the car in front of your place this morning?’ asked Lambell. ‘I noticed it was covered at four o’clock and at a quarter to six the covering was off it.’

‘My son Ralph took it off when he came from the hospital about 5.30.’

‘Has he ever done that before?’

‘No, except on one or two occasions on a Sunday.’

‘Why did he do it this morning?’

‘I told him to do it.’

Unaccountably, according to his notes, Lambell did not at this point ask the obvious follow-up: whose car is it? Instead he solicited details of the night before. Ethel repeated that she had gone to bed about 10.45 p.m., and been awoken at 1.15 a.m. by what she took to be Mollie returning by the side gate: ‘She has sneaked in before without me hearing her and I got up to chastise her.’ Then, according to Lambell’s notes, Ethel said something decidedly odd: ‘I wish you would not make any inquiries into the matter at all. So far as I am concerned, you can let the matter drop.’ From an angry demand the police ‘find out who did it’ to a professed indifference: O’Keeffe, taken aback, stammered about the matter concerning ‘the general public’ and necessitating ‘the fullest enquiries’.

With a growing sense of domestic tensions, Lambell raised the subject of Mollie’s clippings about rooms to let. ‘Was Mollie intending to leave home?’ he asked. Ethel noted that Mollie ‘often talked’ of doing so, but claimed ignorance of any recent plan. There seemed a lot Ethel was unaware of: she was barely aware of Mollie’s friends, and professed to ‘know nothing’ about them. Lambell must have taken his leave with a degree of bafflement. A murder less than ten minutes’ walk from his front door, everything looking so familiar yet sounding so strange.

At first the news was incomplete, the crime having occurred too late for the morning newspapers. When Mervyn Skipper rang Norman Lewis at 8 a.m., it was to convey a partial message. ‘Have you heard the news?’ he asked. ‘Last night Mollie was attacked and outraged. Would you go and break it to Colin as she is dangerously ill?’ Lewis was shocked. ‘Good God,’ he said, and asked his mother, Florence, to accompany him. They arrived at Pangloss to find Colahan in the course of being informed, by a telephone call from Justus Jorgensen’s doctor wife Lil, although she, too, seems to have been unaware that Mollie had died. Colahan looked ‘very distressed’ all the same. He had had, he would say, a foreboding. After his telephone conversation with Mollie, he had gone into his studio to look over some canvases, and Sleep had caught his eye. ‘I had a horrible feeling of fear,’ he would say. ‘I turned out the light so that it should not be visible.’ He would tell Lewis that morning, in fact, that in their last conversation Mollie had ‘seemed to be restless and uneasy’.

As Florence Lewis left, Sue Vanderkelen arrived. It’s unclear whether this was in response to a message, or by prior arrangement. In any case, here she and Colahan were, suddenly closer to a proto-couple than part of a baggy threesome. Norman Lewis stepped discreetly into the lovely garden, bathed in morning sun, while they communed. Others arrived as news travelled: John Farmer from Olinda, Jim Minogue from Malvern, Reg Ellery from Kew. Ellery, medical officer at Mont Park Mental Hospital, took Lewis with him to the Alfred, where Ellery learned of Mollie’s death from the medical superintendent. Still thinking to palliate the blow, Lewis on his return to Pangloss told Colahan: ‘I am afraid there isn’t much hope.’ He finally told Sue when she came into the garden again. From inside he then heard the sound of Colahan weeping. ‘When I saw him a few minutes later,’ Lewis would tell police, ‘he looked absolutely broken up.’

By the afternoon, Colahan had composed himself sufficiently to present at the Detective Office. CIB had recently moved from a dingy muster room on Mackenzie Street into fresher quarters on Russell Street across the road from the City Court, but it was nowhere an artist would conceive of lingering: with the time noted at ‘3.20 p.m.’, he gave a terse, euphemistic statement, detailing in 300 words how he had met Mollie ‘twelve months ago’, become ‘very friendly with her’ and been ‘frequently in her company’, including on the night before with its telephonic epilogue. Did his retelling convince police? They would have come across few like him. Lambell was a returned soldier, O’Keeffe a former bread carter. Colahan was fey, spry, an aesthete and epicure. It was hard to visualise his association with the prim and prickly household into which they had walked in the morning. Seven years earlier, Lambell had achieved a certain renown for arresting Squizzy Taylor. Yet what faced him now was not a case requiring bravery or nerve under fire; rather did it involve the close reading of human natures. The police returned with Colahan to Pangloss, and took some of Mollie’s possessions – perhaps at this stage the manuscript of Monsters Not Men, which would disappear for good. But from Colahan, all police would obtain was that terse one-pager.

Word was now spreading quickly. Children at Mollie’s school were sent home for the day. The Education Department wired Ethel: ‘MINISTER DIRECTOR AND OFFICERS DEPARTMENT EXTEND DEEPEST SYMPATHY IN YOUR SAD BEREAVEMENT’. Whispers round Elwood had brought rubberneckers to Addison Street who encircled the slick of blood in the laneway – one of them, shockingly, was Daniel Blyth, Mollie’s uncle, drawn to the scene of what he first took for an accident. Finally a man arrived with two buckets of sand to ‘stop the ghouls’. This, of course, was not so easy. For afternoon papers such as Sydney’s Sun, Adelaide’s News and Melbourne’s Herald, Mollie Dean’s death was manna. The Sun had its best man on the job, the ubiquitous Hugh Buggy, whose opening paragraph left nothing to the imagination:

Early this morning Miss Molly Dean, aged 25, of Milton Street, Elwood, a teacher at a North Melbourne school, was criminally interfered with, battered about the head and body with a blunt instrument, strangled with her own stocking, and dragged unconscious across Addison Street to a lane within 200 yards of her home and left there to die.

At auction last year, from among a great quantity of papers belonging to Buggy’s descendants, emerged a notebook containing his notes of the ‘Molly Dean Case’, the same pad also containing notations about ‘Mena Griffiths’ and ‘Robert James McMahon’ – murder investigations came pretty much alike to the reporter who claimed to have covered more than two hundred. The notes mingle handwriting, including complete words such as ‘outraged’ and ‘shockingly mutilated’, with Buggy’s famously super-slick Pitman shorthand – a script largely archaic, and now requiring translation. They show Buggy coming quickly to terms with the killing’s disturbing mix of frenzy and calm. ‘Why should stocking have been taken off and tied around throat as it was not possible she could have cried out after first blow was struck [?]’ he asked himself. ‘Why should underclothing have been removed and fastened around her arm [?] It is thought Dean’s murder was actuated by jealousy to point madness or that he deliberately wished convey impression attack was a sex crazed [sic].’ These theories would compete for the remainder of the police’s investigation.

The telephone had rung early in the Leasons’ hallway in Eltham, the children observing their father draw their mother into the bedroom for whispered confidences. Now Percy, too, spoke to Buggy. The expression ‘marked literary ability’ went into the journalist’s notebook: in his story, he would introduce Mollie as a ‘scholar’ and part of ‘a Bohemian circle’.

The cartoonist hazarded crudely how the murder seemed to have been conducted so noiselessly. ‘Knowing the girl and the confidence she had in herself, I do not think that if she had been suddenly confronted by a man she would scream, or that if she had screamed her cry would be very loud,’ Percy said. ‘She was the type who would have calmly said, “What do you want?”, and if attacked would have put up a terrific fight without uttering a sound.’

The Sun reported Ethel as ‘prostrate’. Yet Buggy could charm and wheedle into the securest citadel – he would be the only journalist to interview Captain Francis de Groot, the Sydney Harbour Bridge’s ribbon-cutting rebel – and seems to have found a way. Certainly, he reported impressions that can have come only from the household, that her mother believed Mollie heedless of danger, and had herself experienced a presentiment about its consequences:

Miss Dean’s mother … had a strange premonition last week that her daughter was likely to be injured in some way. When told that her daughter had been seen to alight from a tram late at night and walk home alone, she said that her daughter had no fear. She added that her daughter would walk anywhere alone at night, and said: ‘I know that one of these days the police will come to my house and tell me that she has been killed.’

Chief among reasons for Mollie’s frequent walks home alone, of course, was Ethel’s volatile responses to other visitors, such as Hubert Clifford and Louis Lavater, and a desire to elude her mother’s surveillances. But Buggy was not to know that: Ethel was, as yet, the mother of a martyred daughter.

By late afternoon, the story was rippling across Melbourne on the front page of The Herald, adorned by no fewer than three illustrations. That portrait photograph of Mollie, to prove so ubiquitous, made its first appearance; chaos was embodied in a snapshot of the murder scene, order in an image of Lambell and O’Keeffe’s CIB superintendent. ‘JEALOUSY THEORY IN ELWOOD MURDER’ was floated in the headline, although an alternative was also mooted: ‘It was even suggested that Miss Dean was killed by the same fiend who killed Mena Griffiths, a 12-year-old schoolgirl.’ The inference available was that police had no clue. Imagination, meanwhile, was inflamed by the euphemistic intelligence that there was ‘no evidence of criminal assault’, but that the victim had been ‘outraged in a most dastardly fashion’.

The shock was electrifying. Bookseller Frank Wilmot, who wrote his poetry as Furnley Maurice, shared his Herald with Nettie Palmer when she visited his little bookshop after lunch. She gasped. ‘In town in afternoon Furnley showed me a newspaper report of a girl who was strangled on her way home last night, and said it was Molly Dean, that bright little thoughtful girl,’ she wrote in her diary. ‘Awful for Colahan. She was with Skipper, Leasons and Colahan at the theatre, then went home to Elwood.’ Such things normally never befell ‘people you know’, she noted; it left her able to ‘think of nothing else, but in a numb, shattered way’.

Colahan was no less shattered, perhaps more than he knew. Regrouping at Pangloss after police left, he began to feel he was being watched, and thought he saw through a half-curtained window a man’s legs running across his lawn. Feeling the need to do something, he became possessed with the idea that it might be the decent thing to express condolences personally. ‘Come with me, Johnny,’ he said to Farmer. ‘I don’t want to go over by myself.’ The decision to visit the Deans as a pair, noted Farmer almost four decades later, proved ‘just as well’. When they knocked on the door of 86 Milton Street that evening, Ethel Dean’s initial shock and later prostration had worn off. Here was a representative of that ‘bohemian crowd’; here was the very man who had been with her daughter on her last night. She flew at him in fury. Farmer faltered in his retelling: ‘She made sure he … It was really dreadful.’ Colahan, shaken, was reluctant to return to Pangloss alone, so Farmer drove him to the Jorgensens’ in Brighton, where they all stayed overnight, joined by another Meldrumite in August Cornehls. Their artistic sect had always revelled in attention; now it was drawing together in hopes of inconspicuousness.

Colahan craved the company of friends. On Saturday morning he called the Skippers from the Jorgensens’, asking them over. Lena Skipper, ever practical, brought macaroni for lunch. She was also preoccupied with a comment of the detectives in The Herald that the murderer was likely ‘a jealous hand who wanted revenge’. Lena found this inherently plausible: Mollie’s sauciness, she felt, was bound to drive a man to violence. While Colahan lay on the Jorgensens’ couch, she taxed him. Who might be jealous? Who might know? Norman Lewis, perhaps? Colahan sat up, pale and serious. ‘I know Mollie better than anyone,’ he said firmly. When Lena went on, he elaborated: ‘There are letters of Mollie’s at my house that if the police found them would implicate another who was right out of it.’ Lena could think only of Hubert Clifford, by now safely in England and betrothed. But not even Colahan seemed to have the full picture. ‘There are other letters but I don’t know whose,’ he said.

In fact, Colahan’s mind was racing. He was going back obsessively over his last conversations with Mollie, his sensations of disquiet afterwards, his involvement in precipitating her final walk and, not least, his possible implication as a suspect. How those police had looked at him. He was convinced they had searched Pangloss surreptitiously in his absence, even that they had insinuated a dictaphone into his chimney. When the detectives had stood before a wardrobe in which Mollie’s letters were kept in a shoebox, he had not mentioned them. Ethel Dean was not the only one, then, loath to make investigators welcome, or suddenly impressed by their own powers of prophecy. Mollie’s fate had confirmed Lena in earlier views: that she had been a usurper, a succubus; that she was an inevitable victim of risks she had incurred:

I did not like her [Mollie], she was obsessed with herself and Colin. She was no doubt an extraordinary character, but I had no patience with her … Only in all her actions some monstrously selfish aim. I felt she would do anything to gain her own ends. I often knew what she would do beforehand. I felt she would get some sort of fixation and go straight ahead and defeat her own ends. I thought she may end in gaol. I thought her abnormal and too interested in sex and I did not know exactly what the end of it all would be but I wished she would go to England and leave us all in peace.

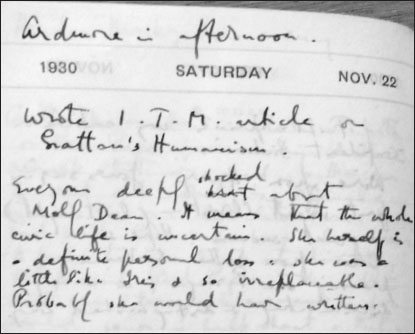

Already, in fact, there had opened a curious divide in attitudes to the death of Mollie Dean. As always, there was a fearful fascination with the possible perpetrator; but in the absence of an obvious suspect, it became as though she had been slain not by an individual but by forces dark and inscrutable, the same as had overwhelmed Mena Griffiths. Some saw the decay of society preceded by a collapse of hope. ‘Everyone deeply shocked about Molly Dean,’ diarised Nettie Palmer that Saturday. ‘It means that the whole civic life is uncertain. She herself is a definite personal loss as she was a little like Iris + so irreplaceable.’ The reference was to Iris Macmahon Ball, the sharp-minded first wife of the political scientist William, victim of tuberculosis in July 1926, aged twenty-six – an exalted comparison, as Nettie had idolised her. In her journal, Nettie confessed to feeling turned outward from her inward-looking life, to seeing Melbourne’s underside and the world’s implicit horrors anew:

I have had no contact with violence before, never imagined it entering my world … Somehow I can’t help feeling that the meaningless tragedy is part of the cloud that has been lowering over the city this past year – the sense of wheels running down … The shabby hawkers drifting from door-to-door … The line of men sitting on the Post Office steps. This isn’t a rational feeling. The murder is surely one of those inexplicable crimes that might be committed any time. But it makes shadowy figures in the street outside seem more sinister, awakens a distrust of life in you, sharpens your sense of violence sleeping beneath the unrevealing surface of these days.

‘Deeply shocked’: Nettie Palmer’s diary

Others saw the case as reflecting the tide of moral laxity. Premier Ned Hogan’s Labor government was wont to commute death penalties – Victoria had not executed a murderer for six and a half years. In that Saturday’s Age featured the first of several letters to see this as more than coincidental with the ‘revolting outrage’ against Mollie Dean. ‘I have grave fears that these outrages will become common for the reason that the principles of the Labor Party are against capital punishment,’ insisted ‘Justice’. ‘The sexual offender is obviously a moral coward, and the fear of the rope holds many of his type in check.’ ‘Periodical floggings’ would also be morally efficacious. The National Council of Women passed a motion deploring ‘recent horrifying crimes’ and demanding life sentences for perpetrators of sex offences. Following so soon on the Griffiths case, the death of Mollie Dean also cast doubt on the Hogan Government’s curtailment of police recruitment. Truth called for the urgent conscription of ‘50 extra constables’ to restore the metropolitan force to strength.

Certainly, the world suddenly looked different. Leason and Skipper, for example, found themselves in a predicament. They had as usual collaborated on a weekly cartoon for The Bulletin, posting it on Wednesday for publication a week hence. It was inspired by tensions in the caucus of federal Labor, led by Bendigo’s Richard Keane MHR, about management of the economic crisis, including the extension of relief to the unemployed and the release of credit by the Commonwealth Bank. Keane had just chosen a menacing metaphor for the intent of his faction, against the will of prime minister and treasurer: ‘The gun is loaded, and it is going off this time.’ Leason duly portrayed a gang of masked desperadoes disgorged by a car labelled ‘Caucus’ menacing a young woman in a virginally white dress bearing the legend ‘Australia’s Credit’ as she walked fearfully down an unlit street. The caption read: ‘FEAR. “If they don’t mean any harm, why do they say such dreadful things?”’ Checking with editor Prior, however, they found it too late to substitute an alternative. It was too late, now, to do many things.