Chapter 6

Off to School

At eight in the morning, standing still under the hot sun, the first day of school was all a bit strange to nine-year-old Clarence. Standing to attention, saying prayers, and singing “God Save the King” with the Union Jack, the British flag, flying overhead. He was familiar with the song and the flag. He had heard “God Save the King” regularly on the radio, as well as at the movie theatres where it was always played before the movies started, with an image of the Union Jack fluttering away on the screen. The movie-goers all stood then too. The prayers were strange though. Not similar at all to those the family said in front of the ancestral altar at home. References to Jesus? Mary? The Holy Spirit? Who were they? These were not concepts that would overly occupy the mind of a kampong boy, but it certainly was something different. He was surrounded by strangers too. The other boys around his age looked just as nervous as he was. The older, more confident boys looked somewhat daunting. Then there were the teachers, most of whom were men dressed in long white cassocks.

After the singing, one of the teachers stood on a stage in front of all the gathered boys and spoke at length in English, a language that Clarence was not entirely comfortable with yet, so the words were somewhat lost on him. The thick Irish accent did not help either.

And so began Clarence’s first day of school – and the end of the carefree days of running around the estate whenever he chose.

__________

Earlier that morning, Clarence, Cecilia, and Connie had jumped into the car that their father had recently purchased, the first for the family on the hill. Hood Hin dropped the girls off first at Katong Convent, the girls’ school run by the Infant Jesus Sisters, before turning back along East Coast Road to Saint Patrick’s, a Catholic boys’ school, to drop off his young and nervous son. Clarence was dressed in white shirt, white shorts, white socks and white canvass shoes, the staple uniform for many schools throughout the tropical locales of the British Empire.

Clarence had passed Saint Patrick’s many times before on the way to East Coast Beach, Marine Parade or Katong. He had often thought how grand and exciting it looked from the outside, especially when he saw students running around playing games in the school yard. That day, it appeared even more so as he stepped in for the first time. It was located on a fifteen-acre plot that still houses the school today. Two grand three-storey brick buildings and a third smaller one held the classrooms, dining halls, and dormitories for many of the teachers and the handful of boarders who came from places like Hong Kong and Christmas Island (which was under the jurisdiction of Singapore at the time). The grounds were beautiful, with a lot more greenery than there is today. Hibiscus, frangipani, and bougainvillea flowered around the property.

On the southern side of the school, where Marine Parade Road now runs, was the beach, with the waters of the Singapore Strait lapping against the boundary of the school. A student in Saint Patrick’s could hear the sound of the waves gently kissing the beach outside the classrooms, and smell the fresh sea air. This was an area that Clarence was very familiar with, having fished and played there many times with his father and friends. The gun emplacements built on the sands by the British as a deterrent to a seaborne attack by the Japanese were still present, providing another reminder of the war. Some sections of the beach near the school were home to fishermen who worked the fish farms just off shore. These men lived in small wooden shacks under the shade of the coconut trees that lined the coast, with their long boats pulled up high enough on the beach in front of their huts to ensure they would not be stolen by the high tide.

__________

It was a somewhat odd bunch of people at school in these early post-war years. The war and the Japanese occupation had really disrupted all areas of life around the island. Many schools were closed for much of that time. Saint Patrick’s itself was closed and commandeered by the 2nd/13th Australian Army General Hospital in the months leading up to the first attacks by the Japanese, in anticipation of casualties from fighting. Then once they captured the island, the Japanese established an administrative centre in the school grounds. When the schools reopened with the return of the British almost four year later, many of the students whose education had been disrupted returned to continue where they had left off. As a result there were now a number of older boys around, some as old as nineteen. As far as Clarence was concerned these were fully grown men. Many of these boys were fairly prominent around school, if not for their size then for their regular appearance during assembly for a six-of-the-best caning. They were always getting into trouble, often for fraternising with the girls up the road at Katong Convent.

This was an era that, looking back with the politically-correct-tinted glasses of today, might be considered very strict schooling. But the boys did not fear it. It was just the way it was. If you followed the rules, did your homework, kept quiet in class, put your hand up, spoke only when spoken to, addressed the teachers appropriately as “Father”, “Sister”, “Brother”, “Sir”, or “Madam”, then you would be fine. And do not fraternise with the girls at Katong Convent.

Saint Patrick’s School was run by the De La Salle Brothers, a Catholic religious order. Also known as the Christian Brothers, they had set up a number of schools around Malaya, as they had in many parts of the world, and Saint Patrick’s was one of the newer ones. The property was originally established in the 1930s as a quiet seaside retreat for the Brothers, until it was soon realised that there was a need for a school in the East Coast districts of Singapore to cater for the growing population there and to take some pressure off Saint Joseph’s Institution, the original Catholic boys’ school downtown near City Hall. While the De La Salle order was originally established in France, the teaching staff at Saint Patrick’s were primarily made up of Irish brothers, supplemented with a small number of lay teachers.

One of the teachers, Brother Anthony, was known around the school as The Watchdog. His reputation preceded him. According to the older boys, Brother Anthony kept a cane inside his long white cassock as he wandered around the courtyard during break time. It was said that he would whip out his cane and strike an unsuspecting transgressor on the spot. Again, it was often the older boys who suffered from his wrath, invariably for something like smoking behind one of the blocks.

Such rumours naturally instilled a sense of fear and curiosity in the new boys. They figured out pretty quickly who Brother Anthony was and tried to spy this supposed hidden cane as the Irishman wandered the yard. Clarence and his friends would soon learn, however, that this man-ofthe-cloth was friendly enough. As always, play by the rules and there was nothing to fear. These older schools were not entirely passionless places that we might sometimes imagine them to have been. For example, the boys were sent home sometimes when it rained and they had become cold and wet. Even in the tropical heat, the presence of rain could drop the temperature just enough to cause the body of a young boy, in wet clothes from playing outside, to shiver when he returned to the classroom. Yes, the teachers were perhaps at times to be feared, but they were fair.

The regimental life of school was a bit of a change for the young kampong kid. Getting up at 7am was not such a big shock to the system, as rural life was driven by sunlight hours and the sun rose a little before 7am anyway. It was more having to be out the door and in the car by 7.30am, then in the school yard for assembly before heading off to a full morning of sitting in a classroom. Up until then life had been about doing a few chores around the house after breakfast before heading off to play amongst the trees, or to catch fish and swim down at the longkang or beach with his brothers, sisters, cousins and friends living nearby. But like all kids, he got used to the new life quickly. Before long he had struck up friendships with new kids from school, and hanging out with them daily gave him something to look forward to.

His subjects were pretty similar to what students cover at school today. Science, English, mathematics, algebra, mechanics, physics, chemistry, geography, and literature. As it was a Catholic school, there was also bible studies. Rugby, football, basketball, track and field, badminton, cross-country running, and cricket were all available and encouraged as extra-curricula activities. Clarence was never a strong runner, but with the annual cross-country race held around the family estate, his local knowledge enabled him to perform a little better than his legs might otherwise have allowed.

While life became more academic and disciplined, these school days never dampened Clarence’s love for the outdoors. If anything they only intensified his passion and his desire to get back outside at the end of the school day and on the weekends. During primary school the students had no after-school sport, so Clarence and his older sisters would head back home in their father’s car when classes finished at 1pm. After eating lunch, doing homework, and running a few chores, he still had plenty of time to go kite flying, catapulting, fishing, or run around, somewhere on the estate.

When Clarence began secondary school at the age of twelve, Hood Hin figured his eldest son was big enough to cycle to school and back, so he was no longer dropped off or picked up by car. One benefit of biking to school was that Clarence, and many of his relatives and school friends, had their own bikes. This meant they had even more freedom to roam further away from the homestead to explore the extended neighbourhood by themselves.

__________

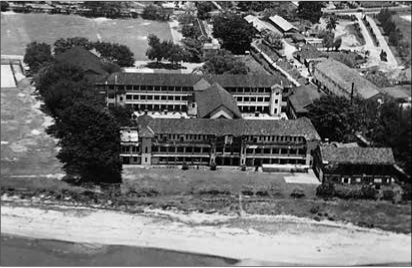

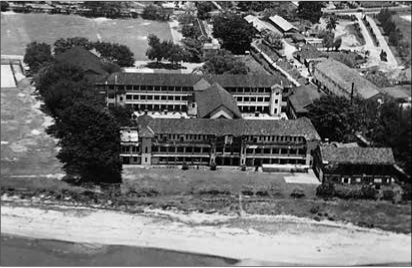

Aerial photo taken from the south, of Saint Patrick’s School, around 1960. The school is sitting on the beach front, where Marine Parade Road now runs. East Coast Road can be made out running along the top of the picture. The longkang, Siglap Canal, that ran along the western edge of Clarence’s estate at Kembangan can be seen running along the right (eastern) border of the school.

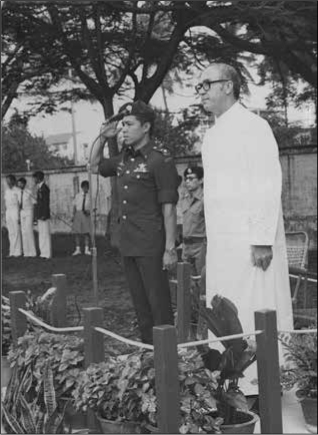

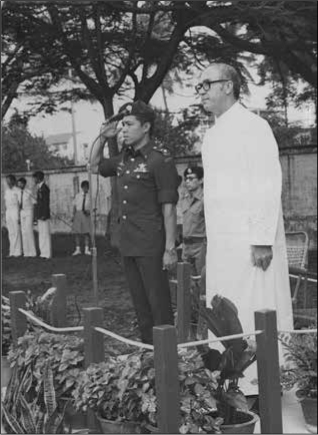

As an old boy of Saint Patrick’s School, Clarence was invited back in the mid to late 1970s to give a talk to the students. On the left is Brother McNally, the principal of the school from 1975 to 1982.

Heading out with his friends from class one Friday afternoon, Clarence suggested they all meet up the next afternoon to go kite fighting. They all agreed enthusiastically and settled on meeting at Karikal Mahal at 1pm the following day. None of them had watches, but they all had clocks at home and lived in the area so there was not much difficulty of keeping to schedule. This was a time well before mobile phones, when many homes did not even have a landline. So plans for after school and weekend activities were made in advance and face to face, and kept to strictly.

Once outside of the school gates, they all farewelled each other, jumped on their bikes, and weaved through the chaos of cars, bikes, and student pedestrian traffic that always formed there on East Coast Road at this time of day. Clarence and his brothers and cousins headed east for about 500m before taking a left up Frankel Avenue, past the residences of some of the British soldiers staying there. Growing up, Clarence never really had much to do with the Europeans, but these folks would smile and wave to the boys as they passed along the dirt road.

As they rode Clarence recalled how it had been a much less relaxed scene a few years earlier during the riots precipitated by the Maria Hertogh custody battle. During three days in November 1950, Malay and Indian Muslims had targeted Europeans and Eurasians all over the island. Clarence witnessed how, in response to this, the British soldiers and their families around Frankel Estate had taken to travelling around in army trucks, and how some of the soldiers had carried weapons as they walked the neighbourhood, sometimes not even in uniform. Apart from this observation, the riots had not caused too much of a problem for Clarence’s family. That did not, however, mean that it was not a major event on the Singapore historical calendar. By the time the riots had been subdued, 18 people had lost their lives: seven Europeans, nine Muslim rioters, and two policemen. It really was a tragic event and one worth reading more details about elsewhere. Among other things, it highlighted the immense cultural and religious difference between the rulers of Malaya at the time, the British, and their subjects.

Shortly after riding through Frankel Estate the boys rode up the hill to the homestead and turned in to their driveway. They then rode around the back of the house, jumped off their bikes, leaned them against the outside rails of the stairs, and ran inside to drop off their bags and get changed. They then headed into the dining room for lunch. Clarence’s younger sisters, Carmen and Christina, and a few of the younger cousins were already there eating lunch.

The young kids all yelled with joy as the older children walked in, the youngest of them running and nearly knocking Clarence over as they hugged his legs. Being twelve years old now, Clarence was practically an adult in their eyes and his return from school was always a moment of great jubilation for them. Very quickly however, Ah Soh had them back to their seats to finish their lunch.

Ah Soh greeted the boys and pointed them to the pot of sayur lodeh that was sitting on the stove in the kitchen. They made their way to the pot of light vegetables cooked in a light yellow soup of coconut milk curry. They each grabbed a bowl, placed in them a few rice cakes, spooned in some sayur lodeh, then took their bowls to the dining table. Soon after they sat down, Connie and Cecilia and the cousins who attended Katong Convent arrived home in the car with Hood Hin at the wheel. They too joined them for lunch.

Daisy entered the dining room to greet them and make sure that everyone was filling their stomachs. This was also the best time of day to dish out chores before the children all disappeared for the afternoon. “Peng,” Daisy called out to her eldest son, putting him in charge of catching some catfish from the pond. Just outside the kitchen were a couple of large concrete tubs of water that held a selection of live fish, placed there so that they could be easily accessed by Ah Soh, or Daisy, or whoever was cooking a meal. The tub’s location meant that fresh fish was always available for breakfast, lunch or dinner, without the women having to go over to the pond to catch some themselves. Furthermore, fish straight from the pond tasted muddy, so a few days in the clear water of these tubs helped clean them out. But the fish did not fly to the tub magically. When this fish supply outside the kitchen ran low, someone had to fish them out of the pond and transport them to the tubs. And invariably that was Clarence’s job.

But first he had to do his homework.

So, once he had finished his lunch, Clarence headed back to the family room, took his books out of his bag, then found a spot on the veranda of the old house to do his work. With the sun still high in the sky, this section between the two houses provided the best shade from the heat of the day. Electricity at the house on Kembangan Hill was a few years away yet, so they always tried to get as much homework done during the daylight hours as they could. They could use kerosene lamps once the sun went down, but these were not tremendously bright, so it was easier to do homework by daylight. While certainly not the top of his class, Clarence was an above-average student and generally did not find his homework too challenging, so it was not long before he was able to head off to do his chores.

As he approached the pond, the little piglets in the pen beside it squealed and scrambled to the fence, thinking that Clarence was coming to feed them. Their large mother lay on her side in the shade, her head in the cool mud, oblivious to the ruckus made by her children. Like many other creatures in the tropics, she knew that the hottest part of the day was a time for rest and not for running around like her little piglets were. Clarence leaned over the fence and scratched their heads as he walked past the pen.

The large pond contained a few species of fish: catfish, snakeheads, gourami. Standing against the pig pen were fishing rods, with lines and hooks. The first thing Clarence did was to bait them up with worms he found in the dirt. Then, one by one, he cast the lines into the pond, and planted the butt end of the rod into the dirt so it would stand by itself. Clarence waited for a while, hoping some fish would quickly snare themselves on the line. After some time, he picked up a rod to check if there was any weight on it, which was a clue that a fish had snared itself. Sometimes, though, the hook was simply caught on one of the submerged logs of wood at the bottom of the pond (that had been left there when the pond was first created). Luckily, this time, there was some weight on the line. Clarence reeled it in, winding the string around a wooden stick. As he did so, the line tightened and slackened in turns, suggesting a fish and not a piece of wood. This was confirmed by splashing on the water surface a few moments later.

With the fish on dry land, he removed the hook from its mouth, and placed it into a bucket of water that he had brought along for the job. He knew that the women would expect more than just one fish, so he checked the other lines, and added a couple more fish to the bucket.

There was other ways to catch fish in the pond. If he had no success with the lines, he could sink a big net into the water and wait for the fish to get trapped in it as they swam around. In the dry season, it was even easier – the fish would be forced to hide in the mud as the water would get quite low, making it hard for them to swim around. All Clarence needed to do then was to wade into the mud and catch them by hand, being careful not to get pricked by the catfish barbs.

With his mission complete, he carried the bucket back to the kitchen area, tipped the fish into the tub, then went to find someone to play with. Friday was here. The weekend had arrived. It was time for more adventure.

__________

When Saturday afternoon rolled around, it was time for kite fighting with his school friends as planned previously. So, after lunch, Clarence picked up his kite and jumped on his bike. He eagerly rode out the driveway, back down Lengkong Tiga, across Upper Changi Road – first stopping to allow a mad bus driver career his vehicle past – then past his school – where a group of students were playing a game of rugby – and finally another 500m or so up the road to the large grassy patch in front of Karikal Mahal.

Karikal Mahal was a landmark in East Coast at the time. It started life as a beachside residence for a rather wealthy Indian cattle merchant. He had bought the large plot of land just east of the shops of Katong in 1917 and built a mansion with four houses for his numerous wives on it. Around the houses were gardens with fountains, sculptures and an artificial lake. On the shorefront side, the residents could take the stairs from their verandas down to the beach. It was a grand place indeed. Palatial. Then in 1947 the property was bought by a rubber company and turned into a hotel. The hotel was given the name Renaissance Grand Hotel, but many, including Clarence and his friends, continued to use the old name of Karikal Mahal. On the northern side of the property, along East Coast Road, was a large open area of grass that would attract children from all over surrounding kampongs and estates to play football or fly kites. Clarence had flown kites many times during his primary school years, but only in the family estate. Now that he had a bike it was a lot more fun to come down here to play.

As the large grassy field came into sight, Clarence stopped his bike at the junction of Still Road. In those days the southern end of Still Road ended at East Coast Road, with Karikal Mahal sitting on the opposite side.12 Clarence looked north up Still Road and noticed two of his buddies, Suan and Teck, waving to him not far away. Once they reached him, the three boys rode across East Coast Road and onto the field.

There were already some other kids playing football on the grass. Clarence and his buddies sometimes joined them. And who knows, perhaps if he had played with them more regularly he may have one day donned the jersey of the Singapore football team, as a number of these regular faces eventually did. Aside from these footballers there were already a few kites in the air, and that was what he and his friends had come for. A battle was about to begin!

The boys rode to the other end of the field where the kite flyers were, jumped off their bikes, and prepared for the fight. The goal of this popular game was to bring down an opponent’s kite by cutting its string as it flew high in the air. To do this, the boys had laced the strings of their kites with ground glass. It was quite a process, but such was the pride of, and therefore preparation required for, a champion kite flyer. During the weekends, in their kampongs or the yards of their houses, young boys all over the island prepared their weaponry by pounding the broken glass of a bottle with a mortar until it was very fine. They then mixed this glass powder with a paste made from animal protein or rice. The string, often cotton stolen from their mother’s sewing kits, was placed into the mixture and stirred with a stick to coat it with this armoury. Once coated, it was hung between a couple of trees to dry, before the boys wound it around a tin can or stick in preparation for the next fight. It always paid to have a number of armoured strings and kites on standby, just in case you ended up having a bad day on the battlefield.

Kneeling on the ground preparing his weapon, Clarence gave out a short “ouch” and grumbled quietly under his breath. He had cut his finger on the string. He shook his finger, which was bleeding very slightly, then stuck it in his mouth to lick his wound clean. The glass was so fine that such injuries were minor, but it always paid to check for imbedded shards after such an incident, as one does for a splinter or prickle. This was one of the risks of this game, but a minor one for these toughened kampong kids. His friends teased him, suggesting his misfortune was an indicator of his performance in the impending fight. In a world where pantangs abound, they had invented their own.

Clarence looked at the other group of boys who were already flying their kites. He suggested to his friends they duel with the other group instead of among themselves. That’s how it was with kite fighting. It was not necessarily a fight between you and your friends. Anyone on the field was fair game. And if you had the biggest, brightest kite, then you were just asking to become the target of others.

In the meantime, more of their school friends had turned up. While these new arrivals prepared their kites, Clarence, Suan, and Teck launched theirs into the air to get a feel for the wind. By this time of day, the afternoon sea breeze was beginning to pick up more, which was ideal for these fights as it ensured the kites fly higher, thus keeping the strings taut. They waited for their buddies to launch their kites. Eyeing up a couple of target kites from the “enemy”, they moved in for the attack. Their opponents were only too eager to have some competition and, once they became aware of the attack, war began.

It was a challenging game, trying to break your enemies’ string. And it was exciting. The players would manoeuvre their kites close to the enemy’s so that the strings touched. Once in contact, they would quickly pull their string down and release it, to create a sawing action intended to cut through the other’s string with the glass coating. Hence, the tautness of the strings created by the afternoon sea breeze was very important. Of course, it was naturally a game of risk. In order to cut the opponent’s string you risked having yours cut by theirs. But that only added to the excitement.

Yells were heard all over the park as the boys tussled with each other. Sometimes, if you had prepared your string well and luck was on your side, it would be a short battle and you would cut your enemies’ line within a few seconds. More often than not, however, long and great struggles would ensue. With a number of fighters joining the cause, the lines would all become entangled.

Cries of success rang out as each battle came to an end with the demise of someone’s kite. “Hanyuuuuuuut!” the boys yelled as the loser’s kite began its fall to the ground. “Hanyut” was Malay for “floated off” or “gone”, and here it meant that someone’s string had been cut and their kite was now floating to the ground. Not only did this cry herald the end of a battle, it was also an invitation for all around, particularly those not holding one themselves, to rush to the stricken kite. The first to reach it was entitled to claim it for himself. While the loser of the battle was allowed to join the race and reclaim his kite, it was no longer his by right: by losing the battle he had forfeited his ownership. Whoever grabbed it first became the new rightful owner. However, with so many kite-chasers stampeding for it, and so many hands grabbing at it, the flimsy structure of paper and small sticks often would not survive to see another fight.

The afternoon proceeded. Each boy had brought a bundle of kites and a few reels of string to ensure he was equipped with enough ammunition to survive a number of defeats. At five cents per kite, it was quite an investment for a young boy at that time. Of course, not having a kite did not mean you were totally out of the game as becoming a kite-chaser always gave you a chance at a new kite.

The boys could play this for hours, as long as the wind allowed. As 5.30pm approached, the number of kids on the field began to dwindle. Dinnertime was fast approaching and, for most, being late for dinner was considered extremely disrespectful to the family. With a long ride back uphill, Clarence wound up his strings, took his leave, and headed back home.

__________

Kite fighting was just one of the many pursuits that Clarence played with his peers. It was certainly one of the more aggressive activities and as such was generally only played by boys. Other days saw Clarence swimming or fishing in the longkang running alongside the estate or down at the East Coast beach by the Malay fishing villages, in front of the school or the beachfront bungalows owned by British, European, and American expatriates and rich Singapore businessmen. If they were lucky, or unlucky as the case probably was, they would spy a naked Brit who had a habit of parading himself on his porch overlooking the sea. Some days, they might find themselves chasing each other around the kampongs or perfecting their catapult skills on the birds around the property. And then there were the school-related sports, such as rugby or soccer, which he would head back to school for after lunch.

For more family leisure activities, the family would often jump in the car and head out to Loyang Beach. Daisy’s father had a small bungalow there, and during the first week of the school holidays the extended family would all stay there. This beach was far more suited for swimming and picnics than the nearby East Coast Beach, which was a little polluted due to the comings and goings of the Malay fishing boats.

And then there were the movies. There were a few indoor theatres around the island, but Clarence and his family and friends often headed to an open-air night cinema nearby. For ten cents a movie they sat outside on wooden benches and watched the show of the day, sometimes even in the rain. Most of the movies in these rural settings were in either Malay or Chinese. English was not widely spoken by the people in the kampongs, so movies from the West were not so popular. From time to time the cinemas were set up within their estate and these Clarence and the family were able to watch for free. It was their land after all.

Clarence’s school years were fun times. Although school had taken away some of the freedom he had enjoyed in his childhood, he was developing an even greater enjoyment of the outdoors. It was not only a chance to simply run around and be a boy, but also as a chance to meet and laugh and engage with others away from the homestead, in the neighbourhoods around the eastern part of Singapore.

__________

After some years the time came to start thinking about what to do once he left school. What to do with his life. He was a good student, but the idea of further study did not attract him. To move into a profession would mean having to qualify for Saint Joseph’s Institute, which was one of the top pre-university schools at the time, and a brother school of Saint Patrick’s. Entry was tough though, and Clarence was not greatly attracted to the idea of more years of hard study. Nor was he attracted to the idea of a professional life, a life indoors. His maternal grandfather, Daisy’s father, had wanted him to go to Australia to study medicine and was prepared to cover the cost of such an education, but he was not interested in that either.

So given he did not want to become a professional and was not interested in further study, he completed his final year of school at the age of eighteen having attained the Overseas Senior Cambridge Exams. Of course, the educational system was British and so were the exams. This qualification would at least open up employment options within the police and the civil service.

Yes, an outdoor life was what he wanted. Exactly what kind of an outdoor life though, he did not know.