Chapter 18

Accentuating Accents

In This Chapter

Defining dialectology

Defining dialectology

Mapping English accents in the United States

Mapping English accents in the United States

Getting a sense of other world Englishes

Getting a sense of other world Englishes

A world without speech accents would be flat-out dull and boring. Actors and actresses would lose their pizzazz, and people would have nobody to tease for sounding funny. All joking aside, accents are extremely interesting and fun to study because, believe it or not, everyone has an accent. Understanding accents helps phoneticians recognize the (sometimes subtle) differences speakers have in their language use, even when they speak the same language.

This chapter introduces you to the world of dialectology and English accents. You peer into the mindset of a typical dialectologist (if such a thing exists) to observe how varieties of English differ by words and by sounds. You then hop on board for a whirlwind tour of world English accents. Take notes and you can emerge a much better transcriber. You may even pick up some interesting expressions along the way.

Viewing Dialectology

People have strong feelings concerning different accents. They tend to think that their speech is normal, but other folks’ speech sounds weird. This line of thinking can go the other extreme with people thinking that they have a strong country or city accent and that they won’t ever sound normal.

Think of the times you may have spoken to someone on the phone and reacted more to the way they sounded than based on what the person actually said. Awareness of a dialectal difference is still a strong feeling many people have. In fact, some phoneticians may argue that judging people based on their dialect is one of the few remaining socially accepted prejudices. Although most people have given up judging others based on their ethnic background, race, gender, sexual orientation, and so forth (at least in public), some people still judge based on dialect. Along comes a Y’all!, Oi!, or Yer! and there is either a feeling of instant bonding or, perhaps, repulsion.

To shed some light on this touchy subject, dialectologists study differences in language. The word dialect comes from the Greek dia- (through) and -lect (speaking). To dialectologists, a language has regional or social varieties of speech (classified as a lect). For example, the United States and Britain have noticeable differences between speaking styles in the South and North (geographic factors). Social speech differences, such as what you may find comparing a tow truck driver and a corporate attorney, also exist.

Furthermore, a village or city may have its own lect. According to this classification system, each individual has his or her own idiolect. Note, an idiolect isn’t the speech patterns of an idiot (although, I suppose an idiot would have his or her own idiolect, too).

Mapping Regional Vocabulary Differences

Dialectologists create dialect maps showing broad dialect regions, such as the West, the South, the Northeast, and the Midwest of the United States. Within these broad areas, they create further divisions called isoglosses, which are boundaries between places that differ in a particular dialect feature.

You can test how you weigh in on this kind of vocabulary variation with this question designed for North Americans:

What do you call a large, made-to-order sandwich on a 6-inch roll?

a.) Hero

b.) Hoagie

c.) Po-boy

d.) Sub

e.) Other

Your answer likely depends on where you live and on your age. If you’re from New York City, you may answer “hero.” If you’re from Philadelphia, you may answer “hoagie.” If you’re from Texas or Louisiana, you may answer "po-boy." The usual champ, “sub,” now seems to be edging out the other competitors, especially for younger folks.

If you answer other, you may refer to this sandwich by a wide variety of names, such as "spucky," "zep," "torp," "torpedo," "bomber," "sarney," "baguette," and so on. For color maps of how approximately 11,000 people responded to this type of question, check out www4.uwm.edu/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_64.html.

Australian:

Australian: www.abc.net.au/wordmap/

British:

British: www.bbc.co.uk/voices/

Canadian:

Canadian: http://dialect.topography.chass.utoronto.ca/dt_orientation.php

Transcribing North American

Dialectologists differ when it comes to dividing up the United States into distinct regional dialect areas. Some favor very broad divisions, with as little as two or three regions, while others suggest fine-grained maps with hundreds of regional dialect areas.

I follow the divisions outlined in the recently completed Atlas of North American English, based on the work of dialectologist William Labov and colleagues. This atlas is part of ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania Telsur (telephone survey) project. The results, which reflect more than four decades of phonetic transcriptions and acoustic analyses, indicate four main regions: the West, the North, the South, and the Midland. Figure 18-1 shows these four regions.

Map by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 18-1: The United States divided into four distinct regional dialect areas.

The first three regions have undergone relatively stable sound shifts, whereas the Midland region seems to be a mix of more variable accents. The following sections look closer at these four regions and the sound changes and patterns that occur in the speech of their locals.

The West Coast: Dude, where’s my ride?

The area marked West ranges from Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico to the Pacific coast. This large region is known mostly for the merger of /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ (for example “cot” versus “caught” and “Don” versus “Dawn”), although this blend is also widespread in the Midland. A common feature of the West is also fronting of /u/. For example, Southern Californian talkers’ spectrograms of /u/-containing words, such as “new,” show second formants beginning at higher-than-normal frequencies (much closer to values for /i/).

In general, these characteristics mark the West:

Rhotic: Rhotic dialects are ones in which final “r” sound consonants are pronounced. For instance, the “r” in “butter.”

Rhotic: Rhotic dialects are ones in which final “r” sound consonants are pronounced. For instance, the “r” in “butter.”

General American English (GAE): This is perceived to be the standard American English accent. It’s typically the accent you would hear used by news anchors.

General American English (GAE): This is perceived to be the standard American English accent. It’s typically the accent you would hear used by news anchors.

Dialectal variability mainly through stylistic and ethnic innovations: Most of the variation in dialect is due to social meaning (style) or variants used by different ethnic groups in the area.

Dialectal variability mainly through stylistic and ethnic innovations: Most of the variation in dialect is due to social meaning (style) or variants used by different ethnic groups in the area.

A rather stereotyped example of such variation is the California surfer, a creature known for fronting mid vowels such as “but” and “what,” pronouncing them as /bɛt/ and /wɛt/. Expressions such as “I’m like . . .” and “I’m all . . .” are noted as coming from young people in Southern California (the Valley Girl phenomenon). Linguists describe these two particular creations as the quotative, because they introduce quoted or reported material in spoken speech.

Other regionalisms in the West may be attributed to ethnic and linguistic influences, for example the substitution of /ɛ/ to /ӕ/ (such as “elevator” pronounced /ˈӕlɪvedɚ/) among some speakers of Hispanic descent, and more syllable-based timing among speakers from Japanese-American communities.

The South: Fixin’ to take y’all’s car

The Southern states range from Texas to Virginia, Delaware, and Maryland. This accent has striking grammatical (“fixin’ to” and “y’all”) and vocabulary characteristics (“po-boy”).

In general, these characteristics mark the South:

Rhotic: However, some dialects of Southern states' English are more non-rhotic.

Rhotic: However, some dialects of Southern states' English are more non-rhotic.

Lexically rich: This dialect has a plentiful, unique vocabulary.

Lexically rich: This dialect has a plentiful, unique vocabulary.

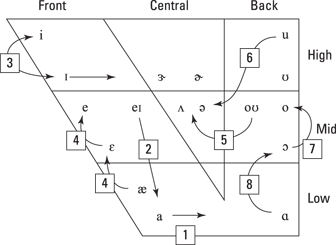

Vowels: One of the most distinct qualities of Southern American English is the difference in vowels compared to GAE. An important phonetic feature of the Southern accent is the Southern vowel shift, referring to a chain shift of sounds that is a fandango throughout the vowel quadrilateral. Figure 18-2 shows this chain shift.

Vowels: One of the most distinct qualities of Southern American English is the difference in vowels compared to GAE. An important phonetic feature of the Southern accent is the Southern vowel shift, referring to a chain shift of sounds that is a fandango throughout the vowel quadrilateral. Figure 18-2 shows this chain shift.

Map by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 18-2: Southern vowel shift

1. Delete your [aɪ] diphthong and substitute an [ɑ] monophthong.

“Nice” becomes [nɑs].

2. Drop your [eɪ] tense vowel to an [aɪ].

“Great” becomes [ɡɹaɪt].

3. Merge your [i]s and [ɪ]s before a nasal stop.

“Greet him” now is [ɡɹɪt hɪ̃m].

4. Merge your [ӕ]s and [ɛ]s.

“Tap your step” becomes [tʰɛp jɚ steɪp].

5. Swing your [ӕ] all the way up to [e].

“I can’t” becomes [aɪ kẽnt].

6. Move your back vowels [u]s and [o]s toward the center of your mouth.

“You got it” becomes [jə ˈɡʌt ɪt].

7. Raise the [ɔ] up to [o] before [ɹ].

“Sure thing” becomes [ʃoɚ θaɪ̃ŋ].

8. Raise [ɑ] to [ɔ] before [ɹ].

“It ain’t hard” becomes [ɪʔ eɪ̃n˺t hɔɚɹd].

Congratulations.

[weɫ ðə ˈmaɪ᷉n θaɪ̃ŋɪz| jə ˈspɪkɪ᷉n ˌsʌðə᷉n‖]

“Well the main thang is ya speakin’ southen” (which means “Well the main thing is you’re speaking Southern,” written in a Southern accent).

In old-fashioned varieties of Southern states English (along with New England English and African-American English), the consonant /ɹ/ isn’t pronounced. Think of the accents in the movie Gone with the Wind. Rather than pronouncing /ɹ/, insert a glided vowel as such:

“fear” as [fiə]

“bored” as [boəd]

“sore” as “saw” [soə]

Another Southern states’ consonant feature is the /z/ to /d/ shift in contractions. The voiced alveolar fricative (/z/) is pronounced as a voiced alveolar stop (/d/) before a nasal consonant (/n/). In other words:

“isn’t” as [ˈɪdn̩t]

“wasn’t” as [ˈwʌdn̩t]

The South is teeming with characteristics that dialectologist enjoy arguing over. Some dialectologists classify different varieties of Southern states English including Upper South, Lower South, and Delta South. Others suggest Virginia Piedmont and Southeastern Louisianan. Yet others disagree with the classifications of the preceding varieties. Say what you will about the South, it’s not boring linguistically.

The Northeast: Yinzers and Swamp Yankees

The Northeast region has a wide variety of accents, strongest in its urban centers: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, Flint, Gary, Syracuse, Rochester, Chicago, and Rockford. Dialectologists identify many sub-varieties, including boroughs of New York City.

Derhoticization: The loss of r-coloring in vowels. This is especially the case in traditional urban areas like the Lower East Side of New York City or in South Boston, whose English is non-rhotic.

Derhoticization: The loss of r-coloring in vowels. This is especially the case in traditional urban areas like the Lower East Side of New York City or in South Boston, whose English is non-rhotic.

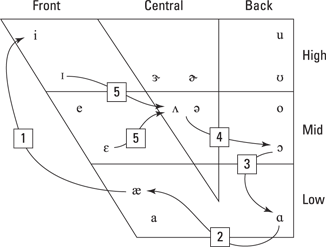

Vowels: Key differences include the Northern cities’ vowel shift and the low-back distinction between [ɑ] and [ɔ].

Vowels: Key differences include the Northern cities’ vowel shift and the low-back distinction between [ɑ] and [ɔ].

Vocabulary distinctions and syntactic forms: For example, swamp Yankees (hardcore country types from southern Rhode Island), and syntactic forms (such as “yinz” or “yunz” meaning “you (plural),” or “y’all” in Southern states accent).

Vocabulary distinctions and syntactic forms: For example, swamp Yankees (hardcore country types from southern Rhode Island), and syntactic forms (such as “yinz” or “yunz” meaning “you (plural),” or “y’all” in Southern states accent).

The accent change in this region goes in the opposite direction than the accent in the Southern states (refer to previous section). It’s a classic chain shift that begins with [æ] swinging up to [i], and ends with [ɪ] and [ɛ] moving to where [ʌ] was. Figure 18-3 shows the Northern cities shift. Follow these steps and pronounce all the IPA examples to speak Northeast like a champ.

1. Change low vowel [ӕ] to an [iə].

“I’m glad” becomes [ə᷉m ɡliəd].

2. Move the back vowel [ɑ] to [ӕ].

“Stop that” becomes [stӕp dӕt].

3. Move the [ɔ] to where [ɑ] was.

“Ah, get out” becomes [ɑː ɡɪt ɑt].

4. Move central [ʌ] to where [ɔ] was.

“Love it” becomes [lɔv ɪt].

5. Move the front [ɛ] and [ɪ] to center [ʌ]/[ə].

“Let’s move it” becomes [ləts ˈmʊv ət].

Map by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 18-3: Northern cities shift.

The Midlands: Nobody home

The Americans in the Midlands decline from participating in the Southern states’ and Northern cities’ craziness. In general, this dialect is rhotic. After that, life gets sketchy and difficult in trying to characterize this region.

The folks in this region are somewhat like the Swiss in Europe, not quite sure when or where they should ever commit. The dialect does exhibit some interaction between [i] and [ɪ] and between [e] and [ɛ], but only in one direction (with the tense vowels laxing). Thus the word “Steelers” is [ˈstɪlɚz] and the word “babe” is [bɛb]. However, like the North, the diphthong [aɪ] is left alone. Thus, “fire” is mostly pronounced [faɪɹ], not [fɑɹ].

Perhaps seeking something exciting, some dialectologists have divided the midlands into a North and a South, with the North beginning north of the Ohio River valley. Dialectologists argue that the North Midlands dialect is the one closest to GAE, or the Standard American Accent heard on the nightly news and taught in school. In this region, the /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ (back vowel) merger is in transition.

The South Midlands accent has fronting of [o] (as in “road” [ɹʌd]). The accent also has some smoothing of the diphthong /aɪ/ toward /ɑ:/. As such, dialectologists consider South Midland a buffer zone with the Southern states.

Pittsburgh has its own dialect, based historically in Western Pennsylvania (North Midland), but possessing a unique feature: the diphthong /aʊ/ monophthongizes (or becomes a singular vowel) to /ɑ/, thus letting you go “downtown” ([dɑ᷉n˺tɑ᷉n]). St. Louis also has some quirky accent features, including uncommon back vowel features, such as “wash” pronounced [wɑɹʃ] and “forty-four” as [ˈfɑɹſɪ.fɑɹ] by some speakers.

Black English (AAVE)

Dialectologists still seem to be struggling for the best name for the variety of English spoken by some black Americans. Many linguists debate the appropriate term to classify this variant. Terms include Black English (BE), Black English Vernacular (BEV), African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), Ebonics (although highly out of favor), or Inner City English (ICE). Also called jive by some of the regular public, it’s up for debate whether this dialect arose from a pidgin (common tongue among people speaking different languages), is simply a variety of Southern states English, or is a hybrid of Southern states English and West African language sources.

I go with AAVE. This variety serves as an ethnolect and socialect, reflecting ethnic and social bonds. Linguists note distinctive vocabulary terms and syntactic usage in AAVE (such as “be,” as in “They be goin’” and loss of final “s,” as in “She go”).

Speakers of AAVE share pronunciation features with dialects spoken in the American South, including the following:

De-rhoticization: R-coloring is lost.

De-rhoticization: R-coloring is lost.

Phonological processes: For example, /aɪ/ becomes [aː]) and /z/ becomes [d] in contractions (such as “isn’t” [ˈɪdn̩t]).

Phonological processes: For example, /aɪ/ becomes [aː]) and /z/ becomes [d] in contractions (such as “isn’t” [ˈɪdn̩t]).

Consonant cluster reduction via dropping final stop consonants, with lengthening: Examples include words, such as “risk” ([ɹɪːs]) and “past” [pӕːs]), and words with (-ed) endings, such as “walked” [wɑːk].

Consonant cluster reduction via dropping final stop consonants, with lengthening: Examples include words, such as “risk” ([ɹɪːs]) and “past” [pӕːs]), and words with (-ed) endings, such as “walked” [wɑːk].

Pronunciation of GAE /θ/ as [t] and [f], and /ð/ as [d] and [v]: At the beginning of words, /θ/ becomes [t], otherwise as [f]. Thus, “a thin bath” becomes [ə tʰɪ̃n bӕf]. Similarly, /ð/ becomes [d] at the beginning of a word and [v], elsewhere, which makes “the brother” [də ˈbɹʌvə].

Pronunciation of GAE /θ/ as [t] and [f], and /ð/ as [d] and [v]: At the beginning of words, /θ/ becomes [t], otherwise as [f]. Thus, “a thin bath” becomes [ə tʰɪ̃n bӕf]. Similarly, /ð/ becomes [d] at the beginning of a word and [v], elsewhere, which makes “the brother” [də ˈbɹʌvə].

Deletion of final nasal consonant, replaced by nasal vowel: The word “van” becomes [væ̃].

Deletion of final nasal consonant, replaced by nasal vowel: The word “van” becomes [væ̃].

Coarticulated glottal stop with devoiced final stop: The word “glad” becomes [ɡlӕːtʔ].

Coarticulated glottal stop with devoiced final stop: The word “glad” becomes [ɡlӕːtʔ].

Stress shift from final to initial syllable: The word “police” becomes [ˈpʰoʊlis] or [ˈpʰoʊ.lis].

Stress shift from final to initial syllable: The word “police” becomes [ˈpʰoʊlis] or [ˈpʰoʊ.lis].

Glottalization of /d/ and /t/: The words “you didn’t” become [ju ˈdɪʔn̩].

Glottalization of /d/ and /t/: The words “you didn’t” become [ju ˈdɪʔn̩].

Canadian: Vowel raising and cross-border shopping

In terms of sound, Canadian English shares many features of GAE, including syllable-final rhotics (for example, “car” is [kʰɑɹ]) and alveolar flaps, [ɾ], as in “Betty” ([ˈbɛɾɪ]). Notable features not common in American English include the following:

Canadian raising: Canadian raising is a well-studied trait in which the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ shift in the voiceless environment. For both of them, the diphthong starts higher. Instead of beginning at /a/, it begins at /ʌ/. Moreover, it typically takes place before voiceless consonants. Thus, these words (with voiced final consonants) are pronounced like GAE:

Canadian raising: Canadian raising is a well-studied trait in which the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ shift in the voiceless environment. For both of them, the diphthong starts higher. Instead of beginning at /a/, it begins at /ʌ/. Moreover, it typically takes place before voiceless consonants. Thus, these words (with voiced final consonants) are pronounced like GAE:

• “five” as [faɪv]

• “loud” as [laʊd]

Whereas the following words get their diphthongs raised, Canadian style:

• “fife” as [fʌɪf]

• “lout” as [lʌʊt]

The behavior of /o/ and /ɛ/ before rhotics: Canadian maintains the /o/ before /ɹ/, where a GAE speaker wouldn't. For "sorry," a GAE speaker would likely say [ˈsɑɹi], whereas a Canadian English speaker would say [ˈsoɹi]. You can listen to a Canadian produce these sounds at

The behavior of /o/ and /ɛ/ before rhotics: Canadian maintains the /o/ before /ɹ/, where a GAE speaker wouldn't. For "sorry," a GAE speaker would likely say [ˈsɑɹi], whereas a Canadian English speaker would say [ˈsoɹi]. You can listen to a Canadian produce these sounds at www.ic.arizona.edu/~lsp/Canadian/words/sorry.html.

Although many Northeastern speakers in the United States distinguish /ɛ/ and /ӕ/ before /ɹ/ (such as pronouncing “Mary” and “merry” as [ˈmӕɹi] and [ˈˈmɛɹi]), many Canadians (and Americans) merge these sounds, with the two words using an /ɛ/ vowel.

A good test phrase for general Canadian English:

“Sorry to marry the wife about now” [ˌsoɹi tə ˈmɛɹi ðə wʌɪf əˌbʌʊt˺ naʊ]

However, this phrase wouldn’t quite work for all Canadian accents, such as Newfoundland and Labrador, because they’re quite different than most in Canada, having more English, Irish, and Scottish influence. These dialects lack Canadian raising and merge the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /ɔɪ/ to [ɑɪ] (as in “line” and “loin” being pronounced [lɑɪ̃n]). They also have many vocabulary and syntactic differences.

If all else fails, a phonetician can always fall back on the /æ/-split in certain loanwords that have [ɑ] in GAE. To see if somebody is from Canada, ask him or her how to pronounce “taco,” “pasta,” or “llama.” If he or she has an /æ/ in these words, the person is probably Canadian.

Transcribing English of the United Kingdom and Ireland

Describing the English dialects of the United Kingdom and Ireland is a tricky business. In fact, there are enough ways of talking in the British Isles and Ireland to keep an army of phoneticians employed for a lifetime, so just remember that there is no one English/Irish/Welsh/Scottish accent. This section provides an overview to some well-known regional dialects in the area.

England: Looking closer at Estuary

Estuary English refers to a new accent (or set of accents) forming among people living around the River Thames in London. However, before exploring this fine-grained English accent, let me start with some basics.

England is a small and foggy country, crammed with amazing accents. At the most basic level, you can define broad regions based on some sound properties. Here are three properties that some dialectologists begin with:

Rhoticity: This characteristic focuses on whether an “r” is present or not after a vowel, such as in “car” and “card.” Large areas of the north aren’t rhotic, while parts of the south and southwest keep r-colored vowels.

Rhoticity: This characteristic focuses on whether an “r” is present or not after a vowel, such as in “car” and “card.” Large areas of the north aren’t rhotic, while parts of the south and southwest keep r-colored vowels.

The shift from /ʌ/ to /ʊ/: In the south, /ʌ/ remains the same, while in the north it shifts to /ʊ/, such that “putt” and “put” are pronounced [pʰʌt] and [pʰʊt] in the south but [ʊ] in the north.

The shift from /ʌ/ to /ʊ/: In the south, /ʌ/ remains the same, while in the north it shifts to /ʊ/, such that “putt” and “put” are pronounced [pʰʌt] and [pʰʊt] in the south but [ʊ] in the north.

The shift from /æ/ to /ɑ/: This division has an identical boundary to the preceding shift. For example, consider the word “bath” [bɑθ].

The shift from /æ/ to /ɑ/: This division has an identical boundary to the preceding shift. For example, consider the word “bath” [bɑθ].

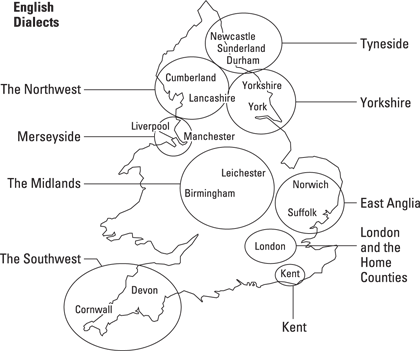

Dialectologists further identify regional dialect groupings within England. Although experts may differ on these exact boundaries and groupings, a frequently cited list includes the following (Figure 18-4 maps these regions):

London and the Home Counties, including Cockney (check out the next section for more information on Cockney)

London and the Home Counties, including Cockney (check out the next section for more information on Cockney)

Kent

Kent

The Southwest (Devon and Cornwall)

The Southwest (Devon and Cornwall)

The Midlands (Leicester and Birmingham) or Brummie

The Midlands (Leicester and Birmingham) or Brummie

East Anglia (Norwich and Suffolk)

East Anglia (Norwich and Suffolk)

Merseyside (Liverpool and Manchester) or Scouse

Merseyside (Liverpool and Manchester) or Scouse

Yorkshire

Yorkshire

The Northwest (Cumberland and Lancashire)

The Northwest (Cumberland and Lancashire)

Tyneside (Newcastle, Sunderland, and Durham), or Geordie

Tyneside (Newcastle, Sunderland, and Durham), or Geordie

Map by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 18-4: A map of England showing accent regions.

Talking Cockney

Cockney is one of the more notable London accents and perhaps the most famous, representing London's East End. Cockney is an urban, social dialect at one end of the sociolinguistic continuum, with Received Pronunciation (RP) at the other. Nobody knows exactly where the word “Cockney” comes from, but it has long meant city person (as in the 1785 tale of a city person being so daft he thinks a rooster neighs like a horse).

θ-fronting: Pronouncing words that in Standard English are normally /θ/ as [f], such as “think” as [fɪŋk] or “maths” as [mɛfs].

θ-fronting: Pronouncing words that in Standard English are normally /θ/ as [f], such as “think” as [fɪŋk] or “maths” as [mɛfs].

Glottal-stop insertion: Inserting a glottal stop for a /t/ in a word like “but” [bʌʔ] or “butter” [ˈbʌʔə].

Glottal-stop insertion: Inserting a glottal stop for a /t/ in a word like “but” [bʌʔ] or “butter” [ˈbʌʔə].

/l/-vocalization: Pronouncing the /l/ in a word like “milk” as [u] to be [ˈmiuk].

/l/-vocalization: Pronouncing the /l/ in a word like “milk” as [u] to be [ˈmiuk].

/h/ dropping: Dropping the /h/ word initially. Pronouncing “head” as [ɛd] or [ʔɛd].

/h/ dropping: Dropping the /h/ word initially. Pronouncing “head” as [ɛd] or [ʔɛd].

Note: Many of these features have now spread to most British accents.

Meanwhile, Cockney also exhibits the following characteristics with vowels:

/iː/ shifts to [əi]: “Beet” becomes [bəiʔ].

/iː/ shifts to [əi]: “Beet” becomes [bəiʔ].

/eɪ/ shifts to [æɪ~aɪ]: “Bait” becomes [bæɪʔ].

/eɪ/ shifts to [æɪ~aɪ]: “Bait” becomes [bæɪʔ].

/aɪ/ shifts to [ɑɪ]: “Bite” becomes [bɑɪʔ].

/aɪ/ shifts to [ɑɪ]: “Bite” becomes [bɑɪʔ].

/ɔɪ/ shifts to [~oɪ]: “Choice” becomes [tʃʰoɪs].

/ɔɪ/ shifts to [~oɪ]: “Choice” becomes [tʃʰoɪs].

/uː/ shifts to [əʉ] or [ʉː] a high, central, rounded vowel: “Boot” becomes [bəʉ] or [bʉːʔ] where [ʉ] is a rounded, central vowel.

/uː/ shifts to [əʉ] or [ʉː] a high, central, rounded vowel: “Boot” becomes [bəʉ] or [bʉːʔ] where [ʉ] is a rounded, central vowel.

/aʊ/ may be [æə]: “Town” becomes [tˢæə̃n].

/aʊ/ may be [æə]: “Town” becomes [tˢæə̃n].

/æ/ may be [ɛ] or [ɛɪ]: The latter occurs more before /d/, so “back” becomes [bɛk] and “bad” becomes [bɛːɪd].

/æ/ may be [ɛ] or [ɛɪ]: The latter occurs more before /d/, so “back” becomes [bɛk] and “bad” becomes [bɛːɪd].

/ɛ/ may be [eə], [eɪ], or [ɛɪ] before certain voiced consonants, particularly before /d/: “Bed” becomes [beɪd].

/ɛ/ may be [eə], [eɪ], or [ɛɪ] before certain voiced consonants, particularly before /d/: “Bed” becomes [beɪd].

Cockney has already moved from its original neighborhoods out toward the suburbs, being replaced in the East End by a more Multiethnic London English (MLE). This accent includes a mix of Jamaican Creole and Indian/Pakistani English, sometimes called Jafaican (as in “fake Jamaican”). A prominent speaker of MLE is the fictional movie and TV character Ali G.

Wales: Wenglish for fun and profit

Wales is a surprising little country. It harkens back to the post-Roman period (about 410 AD). Until the beginning of the 18th century, the population spoke Cymraeg (Welsh), a Celtic language (pronounced /kəmˈrɑːɪɡ/). The fact that Welsh English today is actually a younger variety than the English spoken in the United States is quite amazing.

Currently, only a small part of the population speak Welsh (about 500,000), although this number is growing among young people due to revised educational policies in the schools. Welsh language characteristics and the accent features of the local English accents have a strong interplay, resulting in a mix of different Welsh English accents (called Wenglish, by some accounts).

Characteristics of Wenglish consonants include the following:

Use of the voiceless uvular fricative /χ/: “Loch” becomes [ˈlɒχ] and “Bach” becomes [ˈbɒχ].

Use of the voiceless uvular fricative /χ/: “Loch” becomes [ˈlɒχ] and “Bach” becomes [ˈbɒχ].

Dropping of /h/ in some varieties: Wenglish realizes produces “house” as [aʊs].

Dropping of /h/ in some varieties: Wenglish realizes produces “house” as [aʊs].

Distinction between /w/ and /ʍ/: “Wine” and “whine” become [waɪ̃n] and [ʍaɪ̃n].

Distinction between /w/ and /ʍ/: “Wine” and “whine” become [waɪ̃n] and [ʍaɪ̃n].

Distinction between /yː/ and /ɪʊ/: In “muse” and “mews” and “dew” and “due.”

Distinction between /yː/ and /ɪʊ/: In “muse” and “mews” and “dew” and “due.”

Use of the Welsh /ɬ/ sound, a voiceless lateral fricative: “Llwyd” is [ɬʊɪd] and “llaw” is [ɬau].

Use of the Welsh /ɬ/ sound, a voiceless lateral fricative: “Llwyd” is [ɬʊɪd] and “llaw” is [ɬau].

Tapping of “r”: “Bard” is pronounced as [bɑɾd].

Tapping of “r”: “Bard” is pronounced as [bɑɾd].

Characteristics of Wenglish vowels include the following:

Distinction of [iː] and [ɪə]: As in “meet” ([miːt]) and “meat” ([mɪət]), and “see” ([siː]) and “sea”([sɪə]).

Distinction of [iː] and [ɪə]: As in “meet” ([miːt]) and “meat” ([mɪət]), and “see” ([siː]) and “sea”([sɪə]).

Distinction of [e], [æɪ], and [eɪ]: As in “vane” ([vẽn]),” vain ([væɪ̃n]), and “vein” (veɪ̃n).

Distinction of [e], [æɪ], and [eɪ]: As in “vane” ([vẽn]),” vain ([væɪ̃n]), and “vein” (veɪ̃n).

Distinction of [oː] and [oʊ]: As in “toe” ([toː]) and “tow” ([toʊ]), and “sole” ([soː]) and “soul”([soʊl]).

Distinction of [oː] and [oʊ]: As in “toe” ([toː]) and “tow” ([toʊ]), and “sole” ([soː]) and “soul”([soʊl]).

Distinction of [oː] and [oə]: As in “rode” ([roːd]) and “road” ([roəd]), and “cole” ([kʰoːl]) and “coal” ([kʰoəl]).

Distinction of [oː] and [oə]: As in “rode” ([roːd]) and “road” ([roəd]), and “cole” ([kʰoːl]) and “coal” ([kʰoəl]).

One characteristic for suprasegmentals includes distinctive pitch differences, producing a rhythmic, lilting effect. This accent occurs because when syllables are strongly stressed in Welsh English, speakers may shorten the vowel (and lower the pitch) of the stressed syllable. For instance, in the phrase “There was often discord in the office,” pitch may often fall from “often” to the “dis” of “discord,” but will then rise again from “dis” to “cord.” Also, the “dis” will be short, and the “cord” will be long. This pattern is very different than what’s found in Standard English (British) accents.

Scotland: From Aberdeen to Yell

Scottish English is an umbrella term for the varieties of English found in Scotland, ranging between Standard Scottish English (SSE) at one end of a continuum to broad Scots (a Germanic language and ancient relative of English) on the other. Scots is distinct from Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language closer to Welsh. Thus, Scottish people are effectively exposed to three languages: English, Scots, and Scottish Gaelic.

Varieties of “r” for alveolars: Examples include the alveolar tap (rapid striking of the tongue against the roof of the mouth to stop airflow), such as “pearl” pronounced [ˈpɛɾɫ̩] and the alveolar trill (/r/), such as “curd” pronounced [kʌrd].

Varieties of “r” for alveolars: Examples include the alveolar tap (rapid striking of the tongue against the roof of the mouth to stop airflow), such as “pearl” pronounced [ˈpɛɾɫ̩] and the alveolar trill (/r/), such as “curd” pronounced [kʌrd].

Velarized /l/: An example includes “clan” pronounced [kɫæ̃n].

Velarized /l/: An example includes “clan” pronounced [kɫæ̃n].

Nonaspirated /p/, /t/, and /k/: For instance, “clan,” “plan,” and “tan” would be [kɫæ̃n], [pɫæ̃n], and [tæ̃n]. In contrast, the GAE pronunciation of these words would begin with an aspirated stop (such as [tʰæ̃n]).

Nonaspirated /p/, /t/, and /k/: For instance, “clan,” “plan,” and “tan” would be [kɫæ̃n], [pɫæ̃n], and [tæ̃n]. In contrast, the GAE pronunciation of these words would begin with an aspirated stop (such as [tʰæ̃n]).

Preserved distinction between the /w/ and /ʍ/: An example would be the famous “which/witch” pair, [ʍɪʧ] and [wɪʧ].

Preserved distinction between the /w/ and /ʍ/: An example would be the famous “which/witch” pair, [ʍɪʧ] and [wɪʧ].

Frequent use of velar voiceless fricative /x/: An example includes “loch” (lake) pronounced as [ɫɔx], and Greek words such as “technical” as [ˈtɛxnəkəɫ].

Frequent use of velar voiceless fricative /x/: An example includes “loch” (lake) pronounced as [ɫɔx], and Greek words such as “technical” as [ˈtɛxnəkəɫ].

Characteristics of Scottish vowels are

No opposition of /ʊ/ versus /uː/: Instead, /ʊ/ and /u/ are produced as a rounded central vowel. Thus, “pull” and “pool” are both [pʉɫ].

No opposition of /ʊ/ versus /uː/: Instead, /ʊ/ and /u/ are produced as a rounded central vowel. Thus, “pull” and “pool” are both [pʉɫ].

The vowels /ɒ/ and /ɔ/ merge to /ɔ/: For example, “cot” and “caught” are both pronounced /kɔt/.

The vowels /ɒ/ and /ɔ/ merge to /ɔ/: For example, “cot” and “caught” are both pronounced /kɔt/.

Unstressed vowels often realized as [ɪ]: For example, “pilot” is pronounced as [ˈpʌiɫɪt].

Unstressed vowels often realized as [ɪ]: For example, “pilot” is pronounced as [ˈpʌiɫɪt].

Ireland: Hibernia or bust!

The English language has a venerable history in Ireland, beginning with the Norman invasion in the 12th century and gathering steam with the 16th Century Tudor conquest. By the mid 19th century, English was the majority language with Irish being in second place.

East Coast: It includes Dublin, the area of original settlement by 12th century Anglo-Normans.

East Coast: It includes Dublin, the area of original settlement by 12th century Anglo-Normans.

Southwest and West: These areas have the larger Irish-speaking populations.

Southwest and West: These areas have the larger Irish-speaking populations.

Northern: This region includes Derry and Belfast; this region is most influenced by Ulster Scots.

Northern: This region includes Derry and Belfast; this region is most influenced by Ulster Scots.

Within these broad regions, the discerning ear can pick out many fine distinctions. For instance, Professor Raymond Hickey, an expert on Irish accents, describes DARTspeak, a distinctive way of talking by people who live within the Dublin Area Rapid Transit District.

Like anywhere, accent rivalry occurs. A friend of mine, Tom, from a village about 60 kilometers east of Dublin, was once ranting about the Dubs and Jackeens (both rather derisive terms for people from Dublin) because of their disturbing accent. Of course, when Tom goes to Dublin, he is sometimes called a culchie (rural person or hick) because of his accent.

Rhotic: Some local exceptions exist.

Rhotic: Some local exceptions exist.

Nonvelarized /l/: For instance, “milk” is [mɪlk]. A recent notable exception is in South Dublin varieties (such as DARTspeak).

Nonvelarized /l/: For instance, “milk” is [mɪlk]. A recent notable exception is in South Dublin varieties (such as DARTspeak).

Dental stops replace dental fricatives: For instance, “thin” is pronounced as [t̪ɪn], and “they” as [d̪e:].

Dental stops replace dental fricatives: For instance, “thin” is pronounced as [t̪ɪn], and “they” as [d̪e:].

Strong aspiration of initial stops: As in “pin” [pʰɪ̃n] and “tin” [tʰɪ̃n].

Strong aspiration of initial stops: As in “pin” [pʰɪ̃n] and “tin” [tʰɪ̃n].

Preserved distinction between the /w/ versus /ʍ/, similar to Scottish English: For example, “when” as [ʍɛ̃n] and “west” as [wɛst].

Preserved distinction between the /w/ versus /ʍ/, similar to Scottish English: For example, “when” as [ʍɛ̃n] and “west” as [wɛst].

Hiberno-English has the common characteristics for vowels:

Offglided vowels /eɪ/ and /oʊ/: “Face” and “goat” have steady state vowels outside Dublin, so they’re pronounced [fe:s] and [ɡoːt].

Offglided vowels /eɪ/ and /oʊ/: “Face” and “goat” have steady state vowels outside Dublin, so they’re pronounced [fe:s] and [ɡoːt].

No distinction between /ʌ/ and /ʊ/: In “putt” and “put,” both are pronounced as [ʌ].

No distinction between /ʌ/ and /ʊ/: In “putt” and “put,” both are pronounced as [ʌ].

Distinction between /ɒː/ and /oː/ maintained: In “horse” and “hoarse,” they’re pronounced as [hɒːrs] and [hoːrs], though not usually in Dublin or Belfast.

Distinction between /ɒː/ and /oː/ maintained: In “horse” and “hoarse,” they’re pronounced as [hɒːrs] and [hoːrs], though not usually in Dublin or Belfast.

Here are some common characteristics for suprasegmentals:

Gained syllable: Some words gain a syllable in Irish English, like “film,” pronounced [ˈfɪlə᷉m].

Gained syllable: Some words gain a syllable in Irish English, like “film,” pronounced [ˈfɪlə᷉m].

Lilting intonation: Irish brogue typifies much of the Republic of Ireland (Southern regions), different from the north where there is more falling than rising intonation.

Lilting intonation: Irish brogue typifies much of the Republic of Ireland (Southern regions), different from the north where there is more falling than rising intonation.

Transcribing Other Varieties

English is the main language in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Anglophone Canada and South Africa, and some of the Caribbean territories. In other countries, English isn’t the native language but serves as a common tongue between ethnic and language groups. In these countries, many societal functions (such as law courts and higher education) are conducted mainly in English. Examples include India, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, Tanzania, Kenya, non-Anglophone South Africa, and the Philippines. In this section, I show you some tips for hearing and transcribing some of these accents.

Australia: We aren’t British

Australian English has terms for things not present in England. For instance, there is no particular reason that anyone should expect the land of Shakespeare to have words ready to go for creatures like wallabies or bandicoots. What’s surprising is how Australian English accents have come to differ from those of the mother ship.

The original English-speaking colonists of Australia spoke a form of English from dialects all over Britain, including Ireland and South East England. This first intermingling produced a distinctive blend known as General Australian English. The majority of Australians speak General Australian, the accent closest to that of the original settlers. Regionally based accents are fewer in Australia than in other world English accents, although a few do exist. You can find a map showing these stragglers (with sound samples) at http://clas.mq.edu.au/voices/regional-accents.

As the popularity of the RP accent began to sweep England (from the 1890s to 1950s), Australian accents became modified, adding two new forms:

Cultivated: Also referred to as received, this form is based on the teaching of British vowels and diphthongs, driven by social-aspirational classes. An example is former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser.

Cultivated: Also referred to as received, this form is based on the teaching of British vowels and diphthongs, driven by social-aspirational classes. An example is former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser.

Broad: This accent is formed in counter-response to cultivated, away from the British-isms, emphasizing nasality, flat intonation, and syllables blending into each other. Think Steve Irwin, Crocodile Hunter.

Broad: This accent is formed in counter-response to cultivated, away from the British-isms, emphasizing nasality, flat intonation, and syllables blending into each other. Think Steve Irwin, Crocodile Hunter.

Here are some things you should know about Australian accents:

Like many British accents, Australian English (AusE) is non-rhotic, meaning “r” sounds aren’t pronounced in many words (such as “card” and “leader”).

Like many British accents, Australian English (AusE) is non-rhotic, meaning “r” sounds aren’t pronounced in many words (such as “card” and “leader”).

However, Australians use linking-r and intrusive-r, situations where “r” appears between two sounds where it normally wouldn’t be produced. For example, an Australian would normally pronounce “tuner” without an “r” sound at the end ([ˈtjʉːnə]), but if a word beginning with a vowel follows that word, then the “r” does appear ([ˈtjʉːnəɹ æ̃mp]). This is an example of linking r. See Chapter 7 for more information on linking- and intrusive-r.

However, Australians use linking-r and intrusive-r, situations where “r” appears between two sounds where it normally wouldn’t be produced. For example, an Australian would normally pronounce “tuner” without an “r” sound at the end ([ˈtjʉːnə]), but if a word beginning with a vowel follows that word, then the “r” does appear ([ˈtjʉːnəɹ æ̃mp]). This is an example of linking r. See Chapter 7 for more information on linking- and intrusive-r.

The “r” is produced by making an /ɹ/ and a /w/ at the same time, with lips somewhat pursed.

The “r” is produced by making an /ɹ/ and a /w/ at the same time, with lips somewhat pursed.

Phoneticians divide the AusE vowels into two general categories by length:

Phoneticians divide the AusE vowels into two general categories by length:

• Long vowels consist of diphthongs (such as /æɪ/) and tense monophthongs (such as the vowels /o:/ and /e:/).

• Short vowels consist of the lax monophthongs (such as /ɪ/). See Chapter 7 for more information on English tense and lax vowels.

Here are a couple of AusE vowel features to remember:

• Realization of /e/ as [æɪ]: “Made” sounds like [mæɪd]. This feature is so well known that it’s considered a Shibboleth, a language attribute that can be used to identify speakers as belonging to that group.

• Realization of /u/ as a high, central, rounded vowel, [ʉː]: “Boot” sounds like [bʉːt].

• Realization of /ɑ/ as [ɔ]: “Hot” sounds like [hɔt].

• Realization of /ɛ/ as [eː]: “Bed” sounds like [beːd].

New Zealand: Kiwis aren’t Australian

New Zealand accents are attracting much study because they’re like a laboratory experiment in accent formation. New Zealand didn’t have its own pronunciation until as late as the 19th century when some of the pioneer mining-town and military base schools began forming the first, identifiable New Zealand forms. Although the English colonial magistrates weren’t exactly thrilled with these Kiwi creations, the accents held ground and spread as a general New Zealand foundation accent. Much like the three-way regional dialect split in Australia, cultivated and broad accents were later established as the result of RP-type education norms introduced from England.

New Zealanders also show influences from Maori (Polynesian) words and phrases, including kia hana (be strong), an iconic phrase used following the 2010 Canterbury earthquake.

In recent years, New Zealanders have undergone a linguistic renaissance, taking pride in their accents, noting regional differences (such as between the north and south islands), and often taking pains to distinguish themselves linguistically from other former colonies, such as Australia, South Africa, and the United States.

Some attributes of the Kiwi accent for consonants include the following:

Mostly non-rhotic, with linking and intrusive r, except for the Southland and parts of Otago: For example, “canner” would be [ˈkɛ̃nə] (non-rhotic). Yet, a linking “r” would be found in “Anna and Michael,” sounding like “Anner and Michael” (see Chapter 7 for more information on linking and intrusive “r”).

Mostly non-rhotic, with linking and intrusive r, except for the Southland and parts of Otago: For example, “canner” would be [ˈkɛ̃nə] (non-rhotic). Yet, a linking “r” would be found in “Anna and Michael,” sounding like “Anner and Michael” (see Chapter 7 for more information on linking and intrusive “r”).

Velarized (dark) “l” in all positions: For example, “slap” would be [sɫɛp].

Velarized (dark) “l” in all positions: For example, “slap” would be [sɫɛp].

The merger of /w/ and /ʍ/ in younger speakers, although still preserved in the older generation: Thus, younger New Zealanders would likely pronounce both “which” and “witch” with [w], while their parents would use /ʍ/ and/w/ instead.

The merger of /w/ and /ʍ/ in younger speakers, although still preserved in the older generation: Thus, younger New Zealanders would likely pronounce both “which” and “witch” with [w], while their parents would use /ʍ/ and/w/ instead.

Possibly tapped /w/ and intervocalic /t/: (Intervocalic means between two vowels; refer to Chapter 2.) For example, “letter” is pronounced [ˈɫeɾə].

Possibly tapped /w/ and intervocalic /t/: (Intervocalic means between two vowels; refer to Chapter 2.) For example, “letter” is pronounced [ˈɫeɾə].

Some key characteristics for Kiwi vowels include the following:

Use of a vowel closer to /ə/: A big difference with Kiwi English is the vowel in the word “kit.” Americans use /ɪ/ (and Australians would use /i/), Kiwis use a vowel closer to /ə/. Thus, “fish” sounds like [fəʃ].

Use of a vowel closer to /ə/: A big difference with Kiwi English is the vowel in the word “kit.” Americans use /ɪ/ (and Australians would use /i/), Kiwis use a vowel closer to /ə/. Thus, “fish” sounds like [fəʃ].

Move of /ɛ/ toward [e]: “Yes” sounds like [jes].

Move of /ɛ/ toward [e]: “Yes” sounds like [jes].

Move of /e/ toward [ɪ]: “Great” sounds like [ɡɹɪt].

Move of /e/ toward [ɪ]: “Great” sounds like [ɡɹɪt].

Rise of /ӕ/ toward [ɛ]: “Happy” sounds like [ˈhɛpɪ].

Rise of /ӕ/ toward [ɛ]: “Happy” sounds like [ˈhɛpɪ].

Lowering of /ɔː/ to [oː]: The words, “thought,” “yawn,” and “goat” are produced with the same vowel, [oː]. Americans can have a real problem with this change. Just ask the bewildered passenger who mistakenly flew to Auckland, New Zealand instead of Oakland, California (after misunderstanding Air New Zealand flight attendants at Los Angeles International Airport in 1985).

Lowering of /ɔː/ to [oː]: The words, “thought,” “yawn,” and “goat” are produced with the same vowel, [oː]. Americans can have a real problem with this change. Just ask the bewildered passenger who mistakenly flew to Auckland, New Zealand instead of Oakland, California (after misunderstanding Air New Zealand flight attendants at Los Angeles International Airport in 1985).

South Africa: Vowels on safari

South African English (SAE) refers to the English of South Africans. English is a highly influential language in South Africa, being one of 11 official languages, including Afrikaans, Ndebele, Sepedi, Xhosa, Venda, Tswana, Southern Sotho, Zulu, Swazi, and Tsonga. South African English has some social and regional variation. Like Australia and New Zealand, South African has three classes of accents:

General: Middle class grouping of most speakers

General: Middle class grouping of most speakers

Cultivated: Closely approximating RP and associated with an upper class

Cultivated: Closely approximating RP and associated with an upper class

Broad: Associated with the working class, and closely approximating the second-language Afrikaans-English variety

Broad: Associated with the working class, and closely approximating the second-language Afrikaans-English variety

All varieties of South African English are non-rhotic. These accents lose postvocalic “r,” except (for some speakers) liaison between two words, when the /ɹ/ is underlying in the first, so for example, “for a while” as [fɔɹə'ʍɑːɫ]. Here are some key characteristics of South African English consonants:

Varieties of “r” consonants: They’re usually post-alveolar or retroflex [ɹ]. Broad varieties have [ɾ] or sometimes even trilled [r]. For example, “red robot” [ɹɛ̝d ˈɹeʊbət], where “robot” means traffic light.

Varieties of “r” consonants: They’re usually post-alveolar or retroflex [ɹ]. Broad varieties have [ɾ] or sometimes even trilled [r]. For example, “red robot” [ɹɛ̝d ˈɹeʊbət], where “robot” means traffic light.

No instrusive “r”: “Law and order” is [ˈloːnoːdə], [ˈloːwənoːdə], or [ˈloːʔə̃noːdə]. The latter is typical of Broad SAE.

No instrusive “r”: “Law and order” is [ˈloːnoːdə], [ˈloːwənoːdə], or [ˈloːʔə̃noːdə]. The latter is typical of Broad SAE.

Retained distinction between /w/ and /ʍ/ (especially for older people): As in “which” ([ʍɪʧ]) and “wet” ([wet]).

Retained distinction between /w/ and /ʍ/ (especially for older people): As in “which” ([ʍɪʧ]) and “wet” ([wet]).

Velarized fricative phoneme /x/ for some borrowings from Afrikaans: “Insect” is [xoxə].

Velarized fricative phoneme /x/ for some borrowings from Afrikaans: “Insect” is [xoxə].

/θ/-fronting: /θ/ may be realized as [f]. “With” is [wɪf].

/θ/-fronting: /θ/ may be realized as [f]. “With” is [wɪf].

Strengthened /j/ to [ɣ] before a high front vowel: “Yield” is [ɣɪːɫd].

Strengthened /j/ to [ɣ] before a high front vowel: “Yield” is [ɣɪːɫd].

Strong tendency to initially voice /h/: Especially before stressed syllables, yielding the voiced glottal fricative [ɦ]. For instance, “ahead” is [əˈɦed].

Strong tendency to initially voice /h/: Especially before stressed syllables, yielding the voiced glottal fricative [ɦ]. For instance, “ahead” is [əˈɦed].

Some attributes for vowels in South African English are

Monophthongized /aʊ/ and /aɪ/ to [ɑː] and [aː]: Thus, “quite loud” is [kʰwaːt lɑːd].

Monophthongized /aʊ/ and /aɪ/ to [ɑː] and [aː]: Thus, “quite loud” is [kʰwaːt lɑːd].

Front /æ/ raised: In Cultivated and General, front /æ/ is slightly raised to [æ̝] (as in “trap” [tʰɹæ̝p]). In Broad varieties, front /æ/ is often raised to [ɛ]. “Africa” sounds like [ˈɛfɹɪkə].

Front /æ/ raised: In Cultivated and General, front /æ/ is slightly raised to [æ̝] (as in “trap” [tʰɹæ̝p]). In Broad varieties, front /æ/ is often raised to [ɛ]. “Africa” sounds like [ˈɛfɹɪkə].

Front /iː/ remained [iː] in all varieties: “Fleece” is [fliːs]. This distinguishes SAE from Australian English and New Zealand English (where it can be the diphthongs [ɪi~əi~ɐi]).

Front /iː/ remained [iː] in all varieties: “Fleece” is [fliːs]. This distinguishes SAE from Australian English and New Zealand English (where it can be the diphthongs [ɪi~əi~ɐi]).

West Indies: No weak vowels need apply

Caribbean English refers to varieties spoken mostly along the Caribbean coast of Central America and Guyana. However, this term is ambiguous because it refers both to the English dialects spoken in these regions and the many English-based creoles found there. Most of these countries have historically had some version of British English as the official language used in the courts and in the schools. However, American English influences are playing an increasingly larger role.

As a result, people in the Caribbean code switch between (British) Standard English, Creole, and local forms of English. This typically results in some distinctive features of Creole syntax being mixed with English forms.

At the phonetic level, Caribbean English has a variety of features that can differ across locations. Here are some features common to Jamaican English consonants:

Variable rhoticity: Jamaican Creole tends to be rhotic and the emerging local standard tends to be non-rhotic, but there are a lot of exceptions.

Variable rhoticity: Jamaican Creole tends to be rhotic and the emerging local standard tends to be non-rhotic, but there are a lot of exceptions.

/θ/-interdental stopping: Words like "think” are pronounced using /t/ and words like “this” are pronounced using /d/.

/θ/-interdental stopping: Words like "think” are pronounced using /t/ and words like “this” are pronounced using /d/.

Initial /h/ deleted: “Homes” is [õmz].

Initial /h/ deleted: “Homes” is [õmz].

Reduction of consonant cluster: Final consonant dropped, so “missed” is [mis].

Reduction of consonant cluster: Final consonant dropped, so “missed” is [mis].

Some attributes for vowels are as follows:

Words pronounced in GAE with /eɪ/ (such as “face”) are either produced as a monophthong ([e:]), or with on-glides ([ie]): Thus, “face” is pronounced as [feːs] or [fies].

Words pronounced in GAE with /eɪ/ (such as “face”) are either produced as a monophthong ([e:]), or with on-glides ([ie]): Thus, “face” is pronounced as [feːs] or [fies].

Words pronounced in GAE with /oʊ/ (such as “goat”) are either produced as ([o:]), or with on-glides ([uo]): Thus, “goat” is pronounced as [ɡoːt] or [ɡuot].

Words pronounced in GAE with /oʊ/ (such as “goat”) are either produced as ([o:]), or with on-glides ([uo]): Thus, “goat” is pronounced as [ɡoːt] or [ɡuot].

This difference between monophthong versus falling diphthong) is a social marker — the falling diphthong must be avoided in English to avoid social stigma (if prestige is what the speaker wishes to project).

Unreduced vowel in weak syllables: Speakers use comparatively strong vowels in words such as “about” or “bacon” and in grammatical function words, such as “in,” “to,” “the,” and “over.” This subtle feature adds to the characteristic rhythm or lilt of Caribbean English (for instance, Caribbean Creoles and Englishes are syllable-timed).

Unreduced vowel in weak syllables: Speakers use comparatively strong vowels in words such as “about” or “bacon” and in grammatical function words, such as “in,” “to,” “the,” and “over.” This subtle feature adds to the characteristic rhythm or lilt of Caribbean English (for instance, Caribbean Creoles and Englishes are syllable-timed).

This rich linguistic mix leads to

This rich linguistic mix leads to  Because of the stereotype of an Irish dialect, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that all Irish English accents sound alike. Irish English has at least least three major dialect regions:

Because of the stereotype of an Irish dialect, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that all Irish English accents sound alike. Irish English has at least least three major dialect regions: