SECOND MANASSAS

The Situation, Aug. 15. Lee’s Plan. How it Failed. A Federal Scouting Party. Pope Escapes. Stuart’s Raid. Storm frustrates Efforts Lee plans his Move. Ropes’s Criticism. Jackson’s March. Aug. 26 Manassas Captured. Destruction of Stores. Pope’s Move. Lee and Longstreet’s March. Pope Blunders. Jackson’s Move. Orders Captured. Johnson’s Skirmish. Pope at a Loss. Ewell attacks King. Hard Fighting. Losses. Thoroughfare Gap. Flanking the Gap. The Opposing Forces. Sigel’s Attack. Reno’s and Kearny’s Attack. Hooker’s and Reno’s Attack. Grover’s Brigade. Porter’s Corps. Pope versus Porter. Kearny and Reno Attack. Longstreet takes Position. Longstreet meets King. Pope is Misled. Lee awaits Attack. The Forces. The Lines. A Surprise. Longstreet comes in. The Henry House Hill. Night and Rain. No Pursuit. Centreville Turned. Affair at Ox Hill. Stevens and Kearny. Casualties. The Ammunition Supply.

GEN. LEE had arrived at Gordonsville early on Aug. 15, and taken command. On the 13th McClellan had abandoned his camp at Harrison’s Landing and marched for Fortress Monroe. Lee now left at Richmond but two brigades of infantry to protect the city against cavalry raids, and took the rest of his army to the vicinity of Gordonsville for an aggressive campaign against Pope. He now occupied interior lines between McClellan and Pope, and it behooved him to crush Pope before McClellan’s forces could join him. Lee understood this thoroughly, and Halleck and Pope understood it equally well; but Pope, perhaps inspired by his own boast that he was about to “seek the adversary and beat him when he was found,” and tempted, also, by Jackson’s retreat from Cedar Mountain, had decided to cross the Rapidan and advance upon Louisa C. H. Nothing could have suited Lee’s plans better, but Halleck had not taken entire leave of his senses, and he no sooner heard of Pope’s design to cross the Rapidan than he promptly forbade it. He also, in another letter, told Pope that he had much better be north of the Rappahannock. Lee’s idea of the game the Federals should have played was to retreat to the north side of Bull Run.

Pope’s army had now been reinforced by Burnside, and numbered about 52,000 men. Its left flank rested near Raccoon Ford of the Rapidan, some four miles east of Mitchell Station on the 0. & A. R. R. His centre was at Cedar Mountain, and his right on Robertson’s River, about five miles west of the railroad. He was, therefore, directly opposite Gordonsville, where Jackson’s forces had arrived on the 13th.

About two miles below Rapidan Station was a high hill called Clark’s Mountain, close to the Rapidan, and giving from its top an extensive view of the flat lands of Culpeper, across the river. A signal station was maintained there, and from it the white tents of the Federal camps, marking out their positions, were plainly visible. Spurs of Clark’s Mountain, running parallel to the Rapidan, extended eastward down the river about three miles, to the vicinity of a ford called Somerville’s, two miles above Raccoon Ford. Raccoon Ford was within ten miles of Culpeper C. H., almost as near it as the position of Pope’s army.

Lee, on arriving about 8 A.M. on the 15th, and learning the details of the situation, lost no time. The topography gave him a beautiful opportunity to mass his army (now about 54,000 men) behind Clark’s Mountain, to cross at Somerville Ford, fall upon Pope’s left flank and sweep around it with a superior force, cutting off Pope’s retreat to Washington. Probably at no time during the war was a more brilliant opportunity put so easily within his grasp. He appreciated it, and promptly issued the necessary orders on the very day of his arrival. His army, however, was not yet sufficiently well organized to be called a “military machine,” or to be relied upon to carry out orders strictly. On the contrary, in some respects, it might be called a very “unmilitary” machine, as the history of the failure in this case will illustrate.

Lee, in his report, tells the story very briefly. He says,—

“The movement, as explained in the accompanying order, was appointed for Aug. 18, but the necessary preparations not having been completed, its execution was postponed until the 20th.”

This postponement was the fatal act, for on the 18th the enemy discovered his danger, and in great haste put his army in motion to the rear and fell back behind the Rappahannock, during that day and the next.

The principal failure in the preparations was the non-arrival of Fitz-Lee’s brigade of cavalry at the appointed rendezvous at Verdiersville, near Raccoon Ford, where it was to cross on the morning of the 18th to act upon the right flank of the army. Its commander had duly received orders from Stuart, but had taken the liberty to delay their execution for a day, not supposing that it would make any material difference. Stuart’s report gives the following details:—

“On Aug. 16, 1862, in pursuance of the commanding general’s secret instructions, I put this brigade (Fitz-Lee’s) on the march for the vicinity of Raccoon Ford, near which point the army under Gen. Lee’s command was rapidly concentrating. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee was directed by me to proceed the next day, from near Davenport’s Bridge, opposite Beaver Dam, across to the vicinity of Raccoon Ford, where I promised to join him on that evening (17th). I proceeded on the cars directly to the commanding general, whom I found near Orange C. H.”

After dark on the 17th Stuart arrived at Verdiersville with his staff, having ridden from Orange C. H., but to his surprise could find or hear nothing of Fitz-Lee’s brigade. As it was highly important to communicate with it, he despatched a staff-officer on the road by which the brigade was expected, to find it. Unfortunately, he selected his adjutant-general, Maj. Fitzhugh, who carried Stuart’s copy of Lee’s order of the 15th, disclosing his plan.

This was careless practice, and some blame must, also, rest upon Stuart, for not having given his orders to Fitz-Lee so explicitly that the latter could neither misunderstand or disobey them. For the latter had deliberately marched on the 17th from near Davenport’s Bridge to Louisa C. H. instead of to Verdiersville, as ordered. These three points are very nearly at the angles of an equilateral triangle, with sides of about 20 miles each. Taking his route by Louisa not only occupied two days, but so exhausted his horses that a third day was required to rest them before the proposed movement could be begun. Fitz-Lee made no official report, but in his life of Gen. Lee refers to this occasion, as follows:—

“The brigade commander [Fitz-Lee] he [Stuart] had expected [at Verdiersville] did not understand from any instructions he had received that it was necessary to be at this point on that particular afternoon, and had marched a little out of his direct road in order to reach his wagons, and get from them a full supply of rations and ammunition.”1

Such loose practices may occur a hundred times without any serious result, but once in a while the fate of campaigns will be changed by them, and this was such an occasion. A scouting party of Federal cavalry had been sent across Raccoon Ford on the evening of the 17th, and, in the darkness of the night, Maj. Fitzhugh, searching for the lost brigade, rode into it and was captured. His copy of Lee’s order was taken from him, and on the 18th was delivered to Pope.

Meanwhile, Stuart and his staff had slept in the porch of a house at Verdiersville, and in the morning had been surprised by the Federal scouting party. All managed to escape, but the enemy secured Stuart’s cloak and plumed hat. But the end of the matter was not yet. When no cavalry appeared at Verdiersville, as expected on the night of the 17th, Longstreet ordered two regiments of infantry to be put on picket on the road to Raccoon Ford. The order was brought to Toombs’s brigade, when he was absent, visiting a neighboring brigadier. The senior colonel, however, sent out the regiments, and they were duly posted. Not long afterward Toombs, returning, came upon the regiments, and finding them to be a part of his brigade, ordered them back to camp, claiming that no orders should be obeyed from superior officers which did not come through himself. Thus it had happened that the Federal scouting party got within our lines unannounced. When these facts were developed, Longstreet’s adjutant, in sword and sash, was sent to place Toombs in arrest. He was afterward ordered to Gordonsville and to confine himself to the limits of the town. After a few days, however, he sent an apology and was restored to duty, followed the army, overtook it, and rejoined his brigade, to their great delight, on Aug. 30, in the heat of the battle of Second Manassas.

When Lee learned of the absence of the cavalry, he at first proposed to defer the attack only a single day. Jackson is said to have urged that it would be best to make no delay at all, but to go ahead with the infantry. But the reports from the signal station on Clark’s Mountain represented the enemy as quiet, and Lee decided to wait. Later, a telegraphic despatch from Fitzhugh Lee representing his animals as in bad condition, it was decided to postpone the movement until the 20th, and orders were issued accordingly.

Doubtless, Lee found it hard to believe that Pope, so soon after his boasting order, and still sooner after the “victory” he had claimed at Cedar Mountain, would now turn his back and fly without firing a shot; but, later on that day, there came reports of activity and stir among the enemy’s camps, and on the 19th Lee and Longstreet, going up the mountain to see for themselves, saw Pope’s whole army march away to the Rappahannock.

On the 20th Lee’s advance took place, but although the march was rapidly made in hopes of overtaking some delayed portion of the enemy, the hopes proved vain.

On the north side of the Rappahannock, Pope found such advantages of position that, although for five precious days Lee sought diligently by feints and demonstrations to find a favorable opening, his efforts were vain. But to do nothing was to lose the campaign. By a bold raid of Stuart’s, however, Lee now had the good luck to turn the tables and come into possession of Pope’s private despatch book, with copies of his most important correspondence with Lincoln, Halleck, and others. Stuart had gotten Lee’s permission to try to burn a railroad bridge over Cedar Run, near Catlett’s Station, some 12 miles in rear of Pope’s army. With about 1500 cavalry and two guns, he crossed the Rappahannock at Waterloo Bridge, above Pope’s right flank, on Aug. 22, and pushed on through Warrenton toward Catlett’s Station. A terrific rain-storm came on late in the afternoon, and in it the command captured the enemy’s picket and surprised the Federal encampments. The night was memorable for black darkness, the time being just at the change of the moon. A negro recognized Stuart and volunteered to lead him to the camp of Pope’s staff and baggage. A regiment under W. H. F. Lee raided this camp, while other regiments raided other camps in the vicinity, and a force was sent to burn the bridge. This was impossible on account of the rain, the structure being a two-story trestle. The party had no torpedoes, so a few axes were found and all damage possible was done with them, but it was not serious.

The storm which had prevented Stuart from burning the bridge and hastened his return, also nipped in the bud aggressive operations by both commanders. Jackson, on Lee’s left, had crossed Early’s brigade at Sulphur Springs, upon an old dam across the river, while his pioneers were repairing the broken bridge for a crossing in force. Pope, upon his own left, had designed to cross the Rappahannock and attack Lee’s right flank. The freshet in the river not only called a halt upon both operations, but prevented all the Federal concentrations. Pope made a feeble effort to crush Early’s brigade, but it was repulsed, and when a larger force had been brought up by the Federals, Early had withdrawn over the completed bridge.

Meanwhile, the information gained from Pope’s correspondence showed Lee that his campaign was to be an utter failure, unless, within the next seven days, he could bring Pope to battle upon open ground. For, already, two of the corps of McClellan’s army, the 3d and the 5th, and with Reynolds’s Pa. Reserves, in all 20,000 men, were within two days of juncture with Pope, and the 2d, 4th, and 6th, with Sturgis’s division, and Cox’s 7000 men from Kanawha, could not be more than five days later. Lee had but about 55,000 men. In two days Pope would have about 50,000, and in five days more he would have near 130,000. The situation was desperate, and it required a desperate remedy. Two divisions of infantry,—D. H. Hill’s and McLaws’s,—two brigades under Walker, and a brigade of cavalry under Hampton, which all together would raise Lee’s force to 75,000, had been ordered up from Richmond, but could not be expected in time for the present emergency. Immediate action was necessary. It was taken with the quick decision characteristic of Lee.

Jackson,-with three divisions of infantry (14 brigades about 22,000) and Stuart’s cavalry (two brigades about 2000), set out in light marching order, with no trains but ordnance, ambulances, and a few wagons with cooking utensils, by a roundabout march of over 50 miles, to fall upon Pope’s depot of supplies at Manassas Junction, 24 miles in Pope’s rear, and only 26 miles from Alexandria. Lee, with Longstreet and about 30,000 men, would hold the line of the Rappahannock, and occupy Pope’s attention, while Jackson was making his forced march. Lee’s army, then, of 55,000, would be split in half, and Pope’s army of about 80,000 would be about midway between the two halves. Any military student would pronounce such a situation absolutely ruinous to the divided army.

In his History of the Civil War, Mr. Ropes writes of Lee’s strategy:—

“The disparity between Pope’s force and that of Jackson is so enormous that it is impossible not to be amazed at the audacity of the confederate general, in thus risking an encounter in which the very existence of Jackson’s command would be imperiled, and to ask what was the object which Gen. Lee considered as warranting such an extremely dangerous maneuver. The answer is not an easy one. . . . We shall . . . only remark here that this move of Gen. Lee’s in dividing his army, was an illustration of the daring, not to say hazardous, policy which he pursued in this summer of 1862.”

The best answer is the one given by Lee himself, who is reported in Allan’s Army of Northern Virginia to have said, in referring to some discussion of this matter,—

“Such criticism is obvious, but the disparity of force between the contending forces rendered the risks unavoidable.”

It was scarcely 60 days since Ives, as has been told, stopped his horse in the road to say to me,—

“If there is a man in either army, head and shoulders above all others in audacity, that man is Lee, and you will live to see it.”

There has been speculation whether this turning movement originated with Lee or Jackson. Lee’s report only says,—

“In pursuance of the plan of operations determined upon, Jackson was directed on the 25th to cross above Waterloo,” etc.

Jackson’s report says,—

“Pursuing the instructions of the commanding general, I left Jeffer-sonton on the morning of the 25th,” etc.

The most natural supposition would ascribe the plan to Lee. His own words would seem to confirm the supposition, and Jackson’s form of expression to indorse it.

Col. Henderson, who would certainly assert a claim for Jackson, if it were possible, has written:1—

“It is only certain that we have record of few enterprises of greater daring than that which was there decided on; and no matter from whose brain it emanated, on Lee fell the burden of the responsibility. It is easy to conceive. It is less easy to execute, but to risk cause and country, name and reputation, on a single throw, and to abide the issue with unflinching heart, is the supreme exhibition of the soldier’s fortitude.”

Early on Aug. 25, Jackson set out upon what Henderson calls “his most famous march.” He marched 26 miles that day, and bivouacked very late that night at Salem. His course was first northwest to Amissville, and thence about north to Salem. As his march was intended to be a surprise, it had been favored by the storm of the 23d. This tended to prevent large columns of dust, which so great a movement would surely have raised in dry weather. Considering the object of the march, it was a mistake to allow the infantry regiments to carry their banners displayed. For the country was moderately flat, and was dominated on the east by the Bull Run Mountains; upon which it was to be expected the enemy would have scouts and signal stations. This was actually the case, and the march of the column was observed by 8 A.M. on the 25th, and it was watched for 15 miles, and fair estimates were made of its strength from counting the regimental flags and the batteries. It was plainly seen that their immediate destination was Salem.

This information was promptly communicated to Pope, Halleck, and the leading generals, who began to guess what the movement meant. Naturally, no one guessed correctly; for the simple reason that no one could imagine that Lee would deliberately place his army in a position where Pope could deal with the two halves of it separately. It was correctly guessed that the troops marching to Salem were Jackson’s, but Pope supposed them to be on their way to the Valley and probably covering the flank of Lee’s main body, which might be on their left moving upon Front Royal.

He has been justly blamed for not ordering a strong reconnoissance to develop the true state of affairs. His proper move at the time, as, indeed, it had been for some days, was to fall back with his whole army to Manassas. He would, perhaps, have done this but that Halleck had ordered him to hold especially the lower Rappahannock, covering Falmouth, and to “fight like the devil.”

On the 26th, Jackson marched at dawn, and now the head of his column was turned to the east, and his men knew where they were going. In front of them was Thoroughfare Gap, through the Bull Run Mountains, which debouched upon the heart of the enemy’s territory, held by six times their numbers. A march of about 20 miles brought Jackson to Gainesville, on the Warrenton and Alexandria pike, by mid-afternoon. Here he was overtaken by Stuart with the cavalry. These had skirmished at Waterloo Bridge all day of the 25th, and marched at 2 A.M. on the 26th to follow Jackson’s route. Near Salem, finding the roads blocked by Jackson’s artillery and trains, they had left the roads, and with skilful guides had found passes through the Bull Run Mountains, without going through Thoroughfare Gap. Here Jackson, instead of marching directly upon Manassas Junction, where Pope’s depot of supplies was located, took the road to Bristoe Station, seven miles south of Manassas. There the railroad was crossed by Broad Run. Jackson designed to destroy the bridge and place a force in position to delay the enemy’s approach, while he burned the supplies at Manassas. The head of Ewell’s column reached Bristoe about sunset, having marched about 25 miles.

So far, during this whole day, no report of Jackson’s march had reached the Federals. Now, a train of empty cars, running the gantlet of a hot fire and knocking some cross-ties off the track, escaped going to Manassas, and gave the alarm. While Ewell’s division took position to hold off the enemy, Gen. Trimble volunteered, with two regiments, the 21st Ga. and 21st N.C., to march back and capture Manassas, before it could be reinforced from Alexandria.

Proceeding cautiously in line of battle, it was nearly midnight when these troops were fired upon with artillery from the Manassas works. Losing only 15 wounded, they charged the lines and took them with eight guns. Our cavalry, following the movement, gathered 300 prisoners. Next morning Jackson came up with Taliaferro’s and Hill’s divisions at an early hour, and, about the same time, a Federal brigade, sent by rail from Alexandria, advanced from Bull Run in line of battle, expecting to drive off a raid of cavalry. Had the Confederates restrained their impatience, and permitted the enemy to approach, the whole brigade might have been captured. But their artillery could not resist the temptation to open upon the unsuspecting advance, and it retreated so rapidly that, although it was pursued for some miles, its whole loss was but 135 killed and wounded, and 204 prisoners. The Federal general, Taylor, was killed.

The Federal and sutler’s supplies stored at Manassas presented a sight to the ragged and half-starved Confederates, such as they had never before imagined. Not only were there acres of warehouses filled to overflowing, but loaded cars covered about two miles of side-tracks, and great quantities of goods were stacked in regular order in the open fields, under tarpaulin covers. The supplies embraced everything eatable, drinkable, wearable, or usable, and in immense profusion. During the day, Jackson turned his men loose to feast and help themselves. At night, after astonishing their palates with real coffee, with cheese, sardines, and champagne, and improving their underwear, apparel, and footgear, and filling their haversacks, the torch was systematically applied. When Pope next day looked upon the ashes, he must have felt that it was bad advice, when he said, “Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents and leave our own to take care of themselves.”

Meanwhile, at Bristoe, Ewell had been unmolested until near three o’clock. About that time he was attacked by Hooker’s division. This Pope had sent to develop the situation at Manassas, of which he was as yet not informed. Hooker had only about 5500 men,—less than Ewell had at hand,—but his attack was so vigorous that the latter, whose orders were not to bring on a general engagement, after an hour’s fighting, withdrew across Broad Run (having fought on the south side) and marched to join Jackson at Manassas, without being followed.

Jackson had now accomplished the first object of his expedition—the destruction of the Manassas Depot. Pope would have to abandon his line on the Rappahannock, and would, of course, move at once to crush Jackson. A Napoleon, in his place, might have cut loose from his base and marched upon Richmond, leaving Lee to wreck his army on the fortified lines around Washington, but Pope was no Napoleon. When he realized the situation, however, his first orders were very judicious, a safer play if less brilliant than a Napoleonic advance upon Richmond would have been. He ordered the two corps of McDowell and Sigel, with Reynolds’s division, about 40,000 men, to Gainesville. In support of them, to Greenwich, he sent Heintzelman with three divisions. Hooker was sent to Bristoe to attack Ewell, with Porter marching to support him. Banks, in the rear, protected the trains. The best part of all of these orders was the occupation of Gainesville with a strong force, for Gainesville was directly between Jackson and Longstreet. It behooved Pope to prevent any possible junction between these two, and now on the night of the 27th at Gainesville he held the key to the whole position.

But, unfortunately for Pope, as yet he had no conception that Lee, with Longstreet’s corps, would be hurrying to throw himself into the lion’s den by the side of Jackson. He seems to have thought that his effort should be to “bag Jackson,” rather than to keep him from uniting with Lee.

Let us now turn to Lee and Longstreet. On the 26th, Jackson having about a day and a half the start, Longstreet’s corps set out to follow. One division, Anderson’s, of four brigades, was left at Sulphur Springs, in observation of the enemy, while the remaining 17 brigades, somewhat loosely organized into about five divisions, say 25,000 men, were put in motion to follow in Jackson’s track. Lee rode with this command, and they bivouacked for the night near Orleans. At dawn on the 27th the march was resumed. He was delayed at Salem by some cavalry demonstrations from the direction of Warrenton, and, having no cavalry, he went into bivouac at White Plains, having marched about 18 miles.

I have already told of the course of events having been twice modified in this campaign, by the commanders coming into possession of their rival’s plans or orders, by virtue of some accident, and there is yet to tell of other similar occurrences. Besides these there was also a narrow escape from capture by Lee himself. A Confederate quartermaster, on the morning of the 27th, was riding some distance ahead of Longstreet’s column on the march northward from Orleans. Approaching Salem, he suddenly came upon the head of a Federal squadron. He turned and took to flight, and the squadron, breaking into a gallop, pursued him. Within a short distance the fugitive came upon Lee with some ten or twelve staff-officers and couriers. He yelled out as he approached, “The Federal cavalry are upon you,” and almost at the same instant, the head of the galloping squadron came into view, only a few hundred yards away. It was a critical moment, but the staff-officers acted with good judgment. Telling the general to ride rapidly to the rear, they formed a line across the road and stood, proposing to delay the Federals until Lee could gain a safe distance. This regular formation deceived the enemy into the belief that it was the head of a Confederate squadron. They halted, gazed for a while, and then, wheeling about, turned back, never dreaming of the prize so near.

On the night of the 27th, while Jackson is burning Manassas, Lee and Longstreet are in bivouac at White Plains, 24 miles west and beyond Thoroughfare Gap, while McDowell, Sigel, and Reynolds are about Gainsville, directly between them. In this situation, the game is in Pope’s hands, but, as already said, instead of trying to keep Lee and Jackson apart, his ambition is to make short work of Jackson, who, he probably supposed, would fight in the earthworks around Manassas. In some such belief, during the night he issued further orders. All of his forces were ordered to march upon Manassas at dawn on the 28th. This is the order which lost Pope his campaign.

It is now time to return to Jackson. He knew that Lee and longstreet were coming, and his most obvious move, perhaps, would have been to march for Thoroughfare Gap by some route which would avoid McDowell at Gainesville. His movement, however, had not been made solely to destroy the depot at Manassas. That was but the first step necessary to get Pope out of his strong position. Now it was necessary to bring him to battle quickly, but in detail. His decision was a masterpiece of strategy, unexcelled during the war, and the credit of it seems solely due to Jackson himself.

Soon after nightfall Taliaferro’s division was started on the road toward Sudley’s Ford of Bull Run, to cross the Warrenton turnpike and bivouac in the woods north of Groveton. A. P. Hill’s division was sent by the Blackburn’s Ford road to Centreville. After midnight, Ewell, who had arrived from Bristoe and gotten some supplies, followed Hill across Bull Run. Then he turned up the stream, and made his way on the north side to the Stone Bridge. This he crossed and made a junction with Taliaferro’s division. Hill remained at Centreville until about 10 A.M., when he moved down the Warrenton turnpike, also crossed at Stone Bridge, and, moving up toward Sudley, took position on Jackson’s left. His march and Ewell’s were each about 14 miles. The wagon-trains all went with Taliaferro’s division, which marched about nine miles. The sending of two divisions across Bull Run was doubtless to be in position to interpose if Pope attempted to move past him toward Alexandria. Perhaps, also, it had in it the idea of misleading the enemy, for it certainly had that desirable effect. It happened that a part of Stuart’s cavalry, which was on that flank, during the morning raided Burke’s Station on the railroad, only 12 miles from Alexandria. This, with the reported presence of Hill at Centreville, entirely misled Pope as to Jackson’s true location.

Early on the 28th, two Federal couriers were captured, bearing important orders. Those of the first were from McDowell to Sigel, directing him to march to Manassas Junction. This order was taken to Jackson, and he seems to have interpreted the movement to mean that Pope was about to retreat to Alexandria, for he at once sent orders to A. P. Hill, at Centreville, to move down to the fords of Bull Run to intercept the enemy. But, fortunately, the other captured courier bore orders from Pope to McDowell, ordering the formation of his line of battle for the next day on Manassas plains, and these orders, being brought to Hill, he appreciated that the enemy was not retreating and that it would be dangerous to separate his division from the other two. So, as has been told, about 10 A.M. he marched to join them.

Though it was Jackson’s desire now to conceal his whereabouts until Longstreet was near, yet one of his brigadiers, Col. Johnson, came near, bringing the force which was now marching from Gainesville toward Manasses, down upon the right flank of Taliaferro’s and Ewell’s divisions. Johnson, with two guns, was on a high hill, a little out from Jackson’s extreme right. He saw the head of a column, and skirmishers advancing, as he thought, upon his position. It was the head of Reynolds’s division, on McDowell’s left, straightening itself out for its prescribed march to Manassas, ten miles to the southeast. Johnson opened fire upon them with his guns. The enemy promptly deployed his column, advanced skirmishers, and brought into action a superior force of artillery, on which Johnson abandoned his hill and withdrew his small force to Jackson’s lines. The enemy’s skirmishers advanced and occupied the hill, but the Confederate force was now nowhere to be seen. So it was supposed that the affair was only a demonstration by some reconnoitring party, and, after caring for a few killed and wounded, the division marched for Manassas, where it was still supposed that Jackson was awaiting them.

The Federal marches were not rapid, and it was not until near noon that Pope himself arrived at Manassas, and found that Jackson had mysteriously vanished. He was utterly at a loss to guess where he had gone. His first supposition was that he had gone toward Leesburg, and he ordered McDowell to move to Gum Springs in pursuit. He soon countermanded that order, and hearing oopf Hill’s having been at Centreville, and of the cavalry attack upon Burke’s station, he ordered a general concentration of his troops at Centreville. This was his last order for that day, and all was now quiet for some hours. Jackson and his three divisions lay hidden in the woods within seven miles of the ruins of Manassas, until 5 P.M. At that hour King’s division of McDowell’s corps,—four brigades about 10,000 strong, with four batteries,—appeared upon the Warrenton pike, in front of Jackson’s ambush, marching toward Centreville in pursuance of Pope’s order. King had been marching from Gainesville to Manassas, and Pope’s orders had intercepted the march and changed its direction. Jackson, about a mile from the road, might have remained hidden and allowed King to pass. Had he known that, at that moment, Lee and Longstreet were still beyond Thoroughfare Gap, and that Ricketts’s division of McDowell’s corps was at the gap, one might suppose that he would hesitate to disclose himself. But if Pope was allowed to withdraw behind Bull Run, the result of the whole campaign would be merely to force Pope into an impregnable position. It was the fear of this which led Jackson to attack King immediately, even though he knew that it would draw upon him Pope’s whole force.

Leaving Hill’s division in position on his left (holding the road to Aldie by which he might retreat in case of emergency), Jackson formed a double line of battle, with Taliaferro’s division on the right and Ewell’s on the left. Taliaferro (W.B.) had in his front line from left to right the old Stonewall brigade, now under Baylor, and that of A. B. Taliaferro, and in rear the brigade of Starke. His fourth brigade under Bradley Johnson was detached and in observation near Groveton. Ewell had in his front line Lawton’s and Trimble’s brigades, and in his second Early’s and Forno’s,—in all about 8000 infantry. Orders were sent for 20 pieces of artillery, but owing to difficulties of the ground only two small batteries arrived in time to be engaged. These were isolated and could not be maintained against the superior metal of the enemy. King’s division, not dreaming of the proximity of the enemy, was marching down the pike with only a small advanced guard and a few skirmishers in front. The brigades were in the following order: Hatch’s, Gibbon’s, Doubleday’s, Patrick’s.

The action which now ensued was somewhat remarkable in several features. It was fought principally by the brigadiers on each side. McDowell, in command of the Federal corps, was absent, having gone to find Pope and have a personal conference. The division commander, King, was absent, sick at Gainesville, only about two miles off. Ewell and Taliaferro (W.B.), the two Confederate major-generals, were both seriously wounded, Ewell losing his leg. Probably, for these reasons, less than a half of either force was brought into the brunt of the action. When this had developed itself, Jackson ordered Ewell’s second line, Early and Forno, to turn the enemy’s right flank. In the darkness, they were unable to make their way in time through the woods, and across the deep cuts and high fills of an unfinished railroad, stretching from near Sudley’s Ford toward Gainesville. The fighting, meanwhile, had ceased. The notable part of this action was fought by Gibbon’s brigade of three Wisconsin regiments, and one Indiana reinforced by two regiments of Doubleday’s,—the 56th Pa. and the 76th N.Y.,—in all about 3000 men. Opposed was Taliaferro’s front line of two brigades (A. G. Taliaferro’s on the right, and the Stonewall brigade, now only about 600 strong, under Baylor, on the left) with some help also from Ewell’s front line of Lawton’s brigade, and Trimble’s. These troops were all veteran infantry, and it is to be noted that the decidedly smaller force of the Federals had never before been seriously engaged. They had, indeed, the great aid and support of two excellent batteries, but their desperate infantry fight, attested by their losses, illustrates the high state of efficiency to which troops may be brought solely by drill and discipline. It may be a sort of mechanical valor which is imparted by longtrained obedience to military commands, but it has its advantages, even though there may be appreciable differences in it from the more personal courage inspired by a loved cause.

A good idea of this contest is given in the official report of Gen. W. B. Taliaferro:—

“At this time our lines were advanced from the woods in which they had been concealed to the open field. The troops moved forward with splendid gallantry and in most perfect order. Twice our lines were advanced until we had reached a farm-house and orchard on the right of our line, and were within 80 yards of a greatly superior force of the enemy. Here one of the most terrific conflicts that can be conceived of occurred. Our troops held the farm-house and one edge of the orchard, while the enemy held the orchard and the enclosure next to the turnpike. To our left there was no cover, and our men stood in the open field without cover of any kind. The enemy, although reinforced, never once attempted to advance upon our position, but withstood with great determination the terrible fire which our lines poured upon them. For two hours and a half, without an instant’s cessation of the most deadly discharges of musketry, round shot and shell, both lines stood unmoved, neither advancing and neither broken or yielding until at last, about nine o’clock at night, the enemy slowly and sullenly fell back and yielded the field to our victorious troops.”

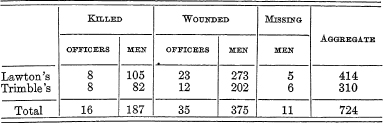

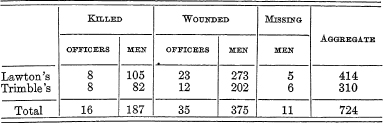

Separate returns for this action were made only for Lawton’s and Trimble’s brigades. Only partial statements for the other commands are found in the few official reports. Of many commands there are no reports, owing to the number of commanding officers who were killed or disabled in succeeding battles. The returns of Lawton’s and Trimble’s brigades are as follows:—

The Stonewall brigade, out of its small force of 600 muskets, lost three colonels, two majors, and over 200 men, killed and wounded. Taliaferro’s brigade lost a lieutenant-colonel and two majors. Its other casualties were probably about 100. Gibbon’s brigade, out of 2300 men, lost about 750, and Doubleday’s two regiments, about 800 strong, lost about 350. Hatch’s brigade, from the front, and Patrick’s from the rear, were not engaged, partly because of the length to which the marching column had been strung out upon the march, and partly, perhaps, because of the absence of Gen. King. But he came upon hearing of the action, and at 1 A.M. on the 29th, by his order, the division was put in motion for Manassas Junction. He thought himself in the presence of superior forces, and decided that it was best to get nearer to reinforcements.

It is now time to return to Lee and Longstreet, who bivouacked between White Plains and Thoroughfare Gap rather early in the afternoon of the 27th. Scouts sent ahead by Longstreet reported the Gap clear, and messages were received from Jackson that he was in ambush upon the Warrenton road. To make sure of the passage through Thoroughfare Gap, D. R. Jones’s division was sent forward to occupy it. The Gap is a narrow pass, only 80 yards in width, bounded on the north by basaltic cliffs over 200 feet in height and on the south by steep hills, rocky, and covered with vines and undergrowth. A small force in possession could hold the pass against any front attack. As Jones’s column drew near the Gap, officers riding ahead discovered the approach of a large Federal force. It was Ricketts’s division, sent by McDowell upon his own responsibility, to prevent the advance of reinforcements to Jackson. It was a move which, quickly made and strongly backed, might have brought victory to the Federals.

Jones deployed the 9th Ga. of Anderson’s brigade, and sent them through the Gap. They met and drove back the Federal pickets, until, meeting heavier forces with artillery, they were themselves driven into the Gap, where the whole brigade formed, and essayed to scale the mountain on the left. This was only possible at a few places, but the 1st Ga. succeeded and got into a good position, and repulsed with loss an attack by the enemy who came so near that some were killed by pistol fire of the officers.

Meanwhile, Benning, commanding Toombs’s brigade, was ordered to occupy the mountain on the right of the pass. He started off at the double-quick, through a hot fire of artillery, and after a stiff climb occupied the crest just in time to repulse the enemy advancing upon it from the other side.

Sharp skirmishing took place until dark. Jones’s division had no artillery, and it could only oppose the enemy’s by selecting men armed with rifled muskets, and sending them as skirmishers to pick off the cannoneers and horses; yet this was done so successfully that the enemy’s batteries were often compelled to move, and Ricketts speaks of his total losses as “severe.” Jones’s total casualties were “about 25.”

One great disadvantage under which the whole Confederate army was still laboring at this period was that most of its arms were the old “calibre 69,” smooth-bore musket, using the round ball with effective range of only about 200 yards. When Benning collected from two regiments all rifled muskets, he got only about 30 from the 20th Ga., and 10 or 12 from the 2d Ga.

When the enemy’s heavy fire of artillery disclosed his force in front of the Gap, Longstreet at once took measures to turn the position. Hood, with his two brigades, was ordered to cross the mountain by a cattle trail a short distance to the north, and Wilcox’s division of three brigades was ordered to force a passage, if necessary, through Hopewell Gap, three miles to the north.

Both of these flank movements were accomplished during the night, but Ricketts had decided not to wait. He had been so discouraged by his reception, that he scarcely waited until nightfall to start back to Gainesville; and at daylight next morning, having learned that King’s division had fallen back to Manassas, Ricketts took the road to Bristoe.

The departure of the enemy from their front at dark on the 27th was observed by the Confederates, and on the morning of the 28th the remainder of Jones’s division marched through the Gap, and was joined by Hood and Wilcox from their respective routes by the cattle trail and Hopewell Gap. By noon Lee and Longstreet had arrived at Gainesville, and connected with Jackson, and the second great step in Lee’s strategy had been successfully accomplished. The third and last, also, by that time was in a fair way of accomplishment, for Pope, instead of concentrating his forces behind Bull Run, had taken the offensive, and had already begun his attack upon Jackson. Of that action it is now to tell.

Jackson’s whereabouts had been disclosed to Pope by the attack upon King’s division, but Pope failed to note that Jackson was the aggressor. He supposed that King had intercepted Jackson in an effort to escape through Thoroughfare Gap. His available forces, on the morning of the 29th, were as follows:—

On Bull Run, two miles east of Jackson, were Sigel’s corps, three divisions, and Milroy’s independent brigade, together about 11,000 strong, and Reynolds’s division of Pa. Reserves, about 8000, with 14 batteries. At Centreville, seven miles to the northeast, were the three divisions of Hooker, Kearny, and Reno, about 18,000. About seven miles to the southeast at Manassas, and between there and Bristoe were the corps of McDowell and Porter, about 27,000,—in all about 64,000.

Jackson’s forces, now about 18,000 infantry, with 40 guns, were formed along the unfinished railroad line, which stretched south from Sudley’s Ford to the Warrenton pike, about three miles. Of this the two miles nearest Sudley were held in force; the rest by skirmishers, except that the right flank, on the Warrenton pike, was held by Early’s and Forno’s brigades of Ewell’s division. The left of the line was held by A. P. Hill’s strong division of six brigades. In front of the extreme left was wide, open ground for a half mile. Then came about a mile of wood from 200 to 600 yards wide, and then again the open, rolling fields. Hill’s division was formed in three lines of battle, with 16 guns to command the open ground in his front.

Ewell’s division, now under Lawton, held the centre, with the brigades of Lawton and Trimble, in two lines. Taliaferro’s division, now commanded by Starke, held the right, formed in three lines of battle, with 24 guns massed to fire over the open ground in front.

Pope was not obliged to fight—certainly not to take the offensive. He might have withdrawn across Bull Run, and awaited the arrival, within two or three days, of Sumner’s and Franklin’s corps and Cox’s division. If he did fight, he would have stood a fair chance of success, had he first massed his army, and concentrated its power in united effort, with reserves to follow up every success. But he was sure to lose if he allowed his divisions to fight in piecemeal.

As Jackson was forming his lines at sunrise, Sigel’s and Reynolds’s columns were visible, nearly two miles away, deploying for the attack. Sigel held the right, with three divisions, supported by Milroy’s brigade. Reynolds held the left. The enemy’s line was not parallel to Jackson’s, their right being nearest to Jackson’s left, and their left somewhat retired. About seven o’clock the enemy’s batteries were brought forward and opened fire. Their skirmishers were advanced, and the lines of battle followed. On the right and the left of Groveton wood (the wood in front of Jackson’s left centre), the Confederate batteries, having fair play, held back the enemy’s advance. Opposite the wood the enemy encountered only skirmish fire, and they easily entered. But when they approached the Confederate line of battle and met its fire, the conflict was short and the Federals retreated, Gregg’s brigade following them. Milroy’s brigade came to their help, but Thomas’s brigade came to Gregg’s, and the Federals were driven completely through the wood and pursued by the Confederate fire as they retreated across the fields.

This much was over by 10.30 A.M. The best of Pope’s opportunity would be lost by 1 P.M., for by that hour Longstreet’s troops would be on hand. But now Reno and Kearny, from Centreville, were beginning to come upon the field, and Sigel, calling upon Reno for reinforcements, again made a desperate assault, which reached the Confederate line in such strength as to necessitate the calling up of Branch’s brigade from Hill’s third line. With this brigade the wood was again cleared and Sigel’s divisions were practically put hors du combat. It was now about noon, and Pope, who had been at Centreville, not realizing the size of the affair near Groveton, arrived upon the field. He immediately organized a fresh attack with the three divisions of Kearny, Hooker, and Reno. Had he awaited their arrival before wrecking Sigel in vain efforts, his chances would have been better.

These three divisions made their assault about one o’clock. As before, the division on the extreme right, Kearny’s, was held off by the 16 guns firing over the open ground on Jackson’s left. The other two divisions came through the wood, and this time portions of the assaulting column actually crossed the railroad line, and fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued, the brunt of it falling upon Field’s and Thomas’s brigades. Field was severely wounded; but Pender’s brigade, from Hill’s third line, joining in the mêlée, the Federals were again borne back, and again pursued, not only through the wood, but out into the open ground beyond, where Pender incautiously followed. Here he met a hot fire of and fell back to the woods.

On seeing his retreat, Grover’s brigade of Hooker’s division, being in reserve, was sent forward for a counterstroke. Advancing slowly through the wood, it gave a volley and then rushed the somewhat disorganized Confederate line, and carried a considerable space. Had they had prompt and ample support, victory was within their grasp.

By this time, Longstreet’s troops had connected with Jackson’s extreme right, relieving the brigades of Early and Forno. These had been brought from their isolated position on the right flank, and placed in the rear of the centre. Jackson had seen Grover’s advance, and now sent Forno’s Louisianians and a regiment of Lawton’s Georgians to the onset. Johnson’s and Starke’s brigades were also brought to fire upon Grover’s left flank. So, caught in the whirlwind of fire which burst upon him in the high tide of his success, Grover was swept back across the line and out of the wood, and driven beyond the Warrenton pike, with a loss of one-fourth of his command.

Four determined assaults had now been made through the Groveton wood, and each had met with a bloody repulse. At least 4000 Federals had fallen in them. Not one attack had had any chance of success, for each had been made with too few men; but the continuous fighting from 7 A.M. until 4 P.M., had also thinned the Confederate lines, and had greatly reduced the ammunition supply of many of the brigades. There was now a lull in the battle for a while, during which many Confederates collected cartridges from the bodies of the fallen. On the right and left of the Groveton wood the fighting had been largely of artillery, or musketry, at long range, and there had been no actual collisions.

Pope had been very sanguine in the morning that he was about to “bag Jackson,” and he was now unwilling to give up the effort, while the sun was still high above the horizon, and while he still had comparatively fresh troops. Kearny’s three brigades opposite the open ground on Hill’s left, had had no close fighting, and Reno’s two brigades were also in good condition. Besides these, he looked for help from Porter’s corps, and from King’s and Ricketts’s divisions of McDowell’s corps. Ricketts could have been with him, but for his blunder in the morning, when he took the road to Bristoe on learning that King had fallen back to Manassas. Thus, Jackson’s attack upon King had produced the effect of keeping two divisions out of the next day’s fight. As to Porter, there is much interesting history which can only be briefly summarized here.

Porter, in the Seven Days, had proved himself not only a hard fighter, but a skilful commander. He would have made a good leader of an army; but he had a low opinion of Pope, and, in his correspondence with brother officers about this period, did not conceal it. It so happened that, under Pope’s orders, Porter’s corps had that morning marched from Bristoe by Manassas for Gainesville. Now, at 4.30 P.M., supposing Porter in position at Gainesville, Pope sent him peremptory orders to immediately attack Jackson’s right flank.

But Porter was not at Gainesville. When, about 11.30 A.M., he reached a little stream called Dawkins Branch, about three and a half miles short of Gainesville, he found Confederate cavalry in his front. He deployed a brigade in line of battle, and, advancing a strong skirmish-line, captured some of Longstreet’s scouts. Meanwhile, clouds of dust, extending back 10 miles to Thoroughfare Gap, indicated that a large force was arriving at Gainesville. Stuart, to notify Jackson of his approach, had made some cavalry drag brush in the roads. Nevertheless, Porter prepared to force his way. He deployed his corps of two divisions in two lines, and advanced a brigade across the stream. King’s division, which was marching in rear of Porter, closed up, but remained in column. About this time McDowell came upon the field and remonstrated with Porter, saying, “You are too far out; this is no place to fight a battle.”

As McDowell ranked Porter, when their troops were together, McDowell was in command. Just before meeting Porter, he had learned that at 8.45 that morning 17 regiments of Confederate infantry and a battery had passed, marching down the Warrenton road toward Groveton. After some reconnoissance, McDowell decided to leave Porter where he was, and to take King back to a road by which he could reach the left flank of Reynolds’s division, now engaged with Jackson’s right. Ricketts’s division, returning from its march to Bristoe, was now following King, but both divisions were exhausted by from 12 to 18 hours’ marchings. When McDowell left, with King and Ricketts, Porter considered himself too weak to venture an attack upon the Confederates in his front. His force was only between 9000 and 10,000. He had no reinforcements at hand and he had in his front Longstreet’s corps of nearly 25,000. His course was proper, and his threatening position practically neutralized an equal number of the Confederates, for D. R. Jones’s division of three brigades, and Wilcox’s of three, were each deployed and held in observation of Porter all the afternoon.

Pope, having sent his order to Porter to attack at 4.30, waited a half-hour to allow time for the message to reach Porter, and at five ordered Kearny and Reno with their five brigades to attack Jackson’s left. To finish with Porter first: The 4.30 order did not reach him until about 6.30. He at once ordered his leading division, Morell’s, to advance, but before the necessary arrangements could be made, darkness had come on, and he was compelled to abandon the idea of attacking. For this, and some other minor incidents, Pope, soon after the battle, preferred charges against Porter. He was tried, and on Jan. 10, 1863, was convicted of violations of articles of war, and sentenced to dismissal from the army, and to be disqualified from ever again holding office under the United States.

Thus was the Federal army deprived of the services of one among its officers of the very highest type. The ex-Federal Confederates who had known Porter considered this result as one of the best fruits of their victory. The gist of the charges against Porter lay in Pope’s claim that Longstreet’s troops had not reached Gainesville until late in the afternoon, and that Porter could have fallen upon Jackson’s exposed right flank. After the war, when official reports of the Confederates were published, the actual facts became so notorious that, in 1878, the proceedings of the court were reviewed by a board appointed by the President. They found the facts and recommended the remission of Porter’s sentence, though condemning the terms in which Porter had criticised Pope, in his correspondence above referred to. This report of the board was referred to Congress, which took no action. Finally on May 4, 1882, President Arthur remitted the sentence.

From this digression let us return to the attack at 5 P.M. on the 29th, by the two divisions of Kearny and Reno with their five brigades. Like the four preceding attacks, it is a predestined failure, for it is another case of a boy sent upon a man’s errand. But, unlike the previous efforts, this gained a temporary success over the thin brigades of A. P. Hill, which had repelled all the preceding ones, and was now poorly supplied with ammunition. Here the thin lines were overrun by the superior numbers, in a very gallant and persistent attack. Hill’s troops were forced back so far that Pope believed that Jackson’s left “was doubled back upon his centre.” He ordered King’s division, which McDowell had now brought upon the field, to advance down the Pike and fall upon Jackson’s right, where, too, he was momentarily expecting Porter to attack.

But Hill, though forced back for perhaps 300 yards, was not broken, and was still making a desperate fight, when, to his aid, came Early’s and Lawton’s brigades. The Federals were in disorder, and the fresh Confederate line had an easy victory, driving the enemy and pursuing them far across the railroad, before it could be halted and brought back. Meanwhile, King’s division, though worn by its march to Manassas and back since 1 A.M. of the previous night, had advanced boldly down the Warrenton pike, stimulated by Pope’s “flattering tale” that Jackson was “doubled back upon his centre.”

Now we must take up the story of Longstreet’s corps to explain the genesis of the sixth and last combat of the day. Like all the preceding, it, too, was made by an insufficient force. Longstreet, on his arrival, had formed his line, not in prolongation of Jackson’s, but inclining forward, making a large obtuse angle. A few of his guns were pushed to the front, firing upon the left of Reynolds’s line, and assisting Jackson’s right in keeping Reynolds’s from coming to close quarters. At the extreme right Jones’s division was bent back, almost at right angles, to oppose a front to Porter’s corps, and Wilcox’s three brigades were held in reserve behind Jones.

Now that his army was again united, Lee was inclined to engage at once, but Longstreet asked to be allowed first to make a personal reconnoissance. After making one, occupying an hour, he reported adversely on account of the easy approach open on his right to large Federal forces reported to be at Manassas. Lee was not satisfied with this report, and recurred to the idea of attacking down the turnpike. It was now so late in the afternoon, however, that Longstreet suggested making only a reconnoissance in force, reserving the attack until dawn next morning, and to this Lee agreed.

Accordingly, Hood’s and Evans’s brigades were ordered to advance for the reconnoissance, and Wilcox’s division was withdrawn from the rear of Jones, as a support to the movement.

Thus it happened that when King’s division advanced, expecting to find Jackson in retreat, it met Longstreet advancing. The fight which ensued was prolonged until 9 P.M. It was fierce and bloody, but the first half-hour of it converted King’s advance into a retreat. He was pursued until he found refuge in the heavy lines holding the high ground about Pope’s centre, with the loss of a gun, several flags, and some prisoners. Longstreet then withdrew his attacking brigades back to the ground from which they had advanced. It had happened also that, although Jackson had been entirely successful on the left, his victorious troops, being withdrawn from the pursuit, had not halted at the railroad cut,—their line during the day,—but had been carried back to a line a short distance in rear, selected by Jackson. Thus, on both flanks, the Federals, although defeated, were left during the night with deserted battle-fields in their front. They discovered the fact before midnight, and this discovery proved to Pope a fatal delusion and a snare. Had it been a deliberate ruse, it would have been a masterpiece. Pope thought it could have but one meaning—that the Confederates were retreating toward Thoroughfare Gap. At daybreak he had wired Halleck as follows:—

“We fought a terrific battle here yesterday, with combined forces of the enemy, which lasted with continuous firing from daylight until dark, by which time the enemy was driven from the field which we now occupy. The enemy is still in our front, but badly used up. We lost not less than 8000 killed and wounded, but from the appearance of the field, the enemy lost at least two to one. The news has just reached me from the front that the enemy is retreating toward the mountains.”

Pope clearly believed this story on the insufficient evidence before him, and this error made him the aggressor next morning and cost him the battle, as we shall see.

The object of the Confederate advance on the afternoon of the 29th, as we have seen, was a reconnoissance preparatory to an attack at dawn, which Longstreet had suggested as better than one so late in the afternoon. Hood and Evans had been charged to examine the enemy’s positions carefully, and to report as to the feasibility of the morning attack. About midnight reports were brought, by each, adverse to making it. Upon these reports Lee decided to stand his ground for the day, and see if the enemy would attack. If he did not, Lee proposed to inaugurate a fresh turning movement around Pope’s right, during the night of the 30th. His force upon the field, including 2500 cavalry, was now nearly 50,000. Jackson, reduced by casualties, had about 17,000. Longstreet had, with R. H. Anderson, about 30,000.

Pope, at last, had united his whole army, except Banks’s corps. This had hardly recovered from its so-called “victory” at Cedar Mountain, and was in charge of the wagon-trains about Bristoe. Before daylight orders had been sent withdrawing Porter from his isolated position on the extreme left, and bringing him around to the centre. And now Pope, believing his victory already half won, had massed, almost under his own eye, about 65,000 men and 28 batteries. Two corps, Sumner’s and Franklin’s, of the Army of the Potomac, and two extra divisions, Cox’s and Sturgis’s,—in all about 42,000,—were coming from Alexandria, 25 miles off, as fast as possible. With these, Pope would have about 107,000 in the field. Lee also had some reinforcements coming, and already at the Rappahannock River. They were the divisions of McLaws and D. H. Hill, each about 7000; Walker’s division about 4000; Hampton’s cavalry 1500, and Pendleton’s reserve artillery 1000—total 20,500.

Having telegraphed Halleck that the Confederates were retreating, Pope now began to set his army in battle array to press the retreat. Some hours’ were consumed, but they were well spent in forming his troops, thus avoiding the isolated efforts of the previous day, and arranging for a simultaneous attack along the whole line. Meanwhile, there was some artillery firing at rather long range by each side, and skirmishers in front were everywhere in easy range and sharply engaged.

The Federal line was short and strong. From its right on Bull Run in front of Jackson’s left, to its left across the Warrenton pike, near Groveton, was less than three miles. Within this space were deployed about 20,000 infantry in the front line, and behind it 40,000 more were held in masses to be thrown where needed. Lee’s line covered at least four miles. Jackson, on the left, had proved the strength of his unfinished railroad as a defensive line of battle, and had no wish to change. But, with his instinctive desire to mystify his opponent, he had withdrawn his men into the nearest woods and hollows, where he kept them carefully out of sight. He had had but one reinforcement from Longstreet’s corps—a battalion of 18 guns under Col. S. D. Lee, which early that morning had taken position on his right flank, where it could support the fire of the large battery near his centre. Longstreet’s line, as before said, was not a prolongation of Jackson’s, but bent to the front—the two forming a rather flat crescent, its right flank overlapping Pope’s left considerably. The Federal army made a finer display than was often seen on a battle-field in the war, being closely concentrated upon ground unusually open, and Pope, from one of the hills close in rear of the centre, viewed it with pride and confidence. Of his opponents he could see little but a few batteries, supported by little more than skirmishers; and he so firmly believed that Jackson was already retreating, that he would not be convinced by those of his officers who had had evidence of large forces near at hand, behind the Confederate skirmish-lines. A Federal who had been captured, and held a prisoner in the Confederate lines during the night, but who had escaped, reported that he had overheard Jackson’s men say that they were going to join Longstreet. Porter had sent the man to Pope, with a message discrediting the story, and suggesting that he might have been deceived or sent as a ruse. Reynolds, on the left, had discovered that the Confederate line overlapped the Federal, and had had a narrow escape from capture. Ricketts had fought Longstreet at Thoroughfare Gap on the 28th and retreated before his advance; but the tale of the escaped prisoner was credited in preference to any other theory. About noon a swarm of skirmishers advanced along the whole Federal front, and were followed by the Federal line of battle, arrayed generally, three lines deep in front.

The Confederate artillery wasted but little fire on the skirmishers. When, however, the triple lines of battle revealed themselves, there happened something for which Pope was not prepared. Not only did every Confederate gun open a rapid fire, but above their roar could be heard the infantry bugles of Jackson’s corps, and from the woods a wave of bayonets swept down to the unfinished railroad, and now Jackson and Longstreet were united, and Pope, with a force only 30 per cent superior, was committed to the attack. Possibly the Confederates may have flattered themselves that their victories in the six assaults made on the previous day would have diminished the ardor of the coming attack, but if so, they were to be disappointed. The value of discipline and training was again illustrated, and the battle which followed was scarcely surpassed for desperation upon either side in the war. The whole weight of the assault fell upon Jackson’s corps. His men defended themselves with courage and the confidence inspired by their recent successes. When, at one point of the line, the ammunition ran low, men laid down muskets, and standing on the railroad embankment, made formidable missiles of an abundant outcrop of large pebbles. At length Pope’s superior force produced such a pressure that Jackson called for assistance, and Lee ordered Longstreet to send a division of infantry. But Longstreet had discovered that the left flank of the attack upon Jackson had now advanced into the reentrant angle between his front and Jackson’s, so far that its lines of battle now presented their flanks and could be enfiladed. He believed that he could most quickly relieve Jackson by a severe enfilade fire of artillery.

Several batteries of artillery were rushed into a suitable position and opened upon the enemy’s flank at easy range a raking fire which nothing could withstand. Within 15 minutes the aspect of the field was changed.

When Pope had first seen Jackson’s corps disclose itself and re-occupy its defensive line along the unfinished railroad, he had very injudiciously withdrawn Reynolds’s division from his extreme left and placed it in support of Porter’s corps, although Milroy’s corps, from among his masses in reserve, was equally available. In vain, now, were Reynolds and all his other reinforcements advanced to stem the tide of retreat across the open meadows, under the Confederate fire. Porter’s triple lines had been practically merged into one, as the successive brigades came to the support of those in front. The merged forces were still pressing forward, and in close proximity to the Confederate line, when the flanking fire of the artillery opened, and quickly disorganized the attack. Jackson added to the confusion by advancing two brigades in a counter-stroke, and Pope’s battle was lost. Unfortunately for Lee, Pope had not opened his battle early enough in the day to allow time for the Confederates to win a victory and to reap its full fruits. It was now about 4 P.M. when Lee, seeing the effects of Longstreet’s fire, ordered his whole force to be advanced for a counter-stroke. Had the Confederate army been a well-organized force, able to bring quickly into play its full powers, much fruit might even yet have been gathered.

The objective point aimed at by Longstreet’s advance was the plateau of the celebrated Henry house, upon which Jackson’s brigade, “standing like a stone wall,” had made his name immortal 13 months before.

Around this plateau the regulars and others of the best Federal troops, both of infantry, cavalry, and artillery, now made desperate stands, appreciating that its possession by the Confederates would cut off the Federal retreat across Bull Run, via the pike and the Stone Bridge. Their stand was also aided by two circumstances. First, Jackson’s division, now greatly worn and reduced by their incessant fighting for three days, and having more exposed ground to advance over, were not able to push the enemy’s retreat as rapidly in the counter-stroke as Longstreet could upon the right. Consequently Pope was able to bring over some reinforcements to his left flank from his right, and his artillery was able to take in flank those of Longstreet’s forces which led the assault upon the Henry hill. Secondly, three of Longstreet’s brigades were lost from his attack from looseness of organization. Wilcox’s, Pryor’s, and Featherstone’s brigades had been called a division, and Wilcox ordered to command them as such. In the progress of the fighting, during the afternoon, Pryor’s and Featherstone’s brigades had become separated from Wilcox’s, just when it was called for by Longstreet, and carried to assist the attack upon the Henry hill. The other two took some part upon the right flank of Jackson, but the weight of the division as a whole was lost. Drayton’s brigade of D. R. Jones’s division, also without orders, was taken by some unauthorized person to oppose a rumored advance of cavalry upon our right flank. The rumor proved to be unfounded, but the brigade was kept out of the action until the fighting was terminated by darkness.

Daylight was shortened by heavy clouds, and a rain which set in about dusk and continued during the night and much of the next day. Although the firing was kept up quite severely for some time after dark, the attack was practically over as soon as daylight was gone. For the irregular and disconnected lines, though with ample spirit and force to carry the position, had time permitted them to envelop it, were paralyzed by the danger of firing into each other in the darkness.

In the Federal army the confusion was very great, as troops and trains intermixed groped through the rain, and poured across the bridge and along the pike toward Centreville. There Franklin’s corps had arrived about 6 P.M., only a few hours too late to have come upon the field and have saved the day. Upon this corps Pope ordered his whole army to concentrate.

An officer of the regular army, Capt. W. H. Powell, describing this night march, wrote in the Century War Book, as follows:—

“As we neared the bridge we came upon confusion. Men, singly and in detachments, were mingled with sutler’s wagons, artillery caissons, supply wagons, and ambulances, each striving to get ahead of the other. Vehicles rushed through organized bodies, and broke the column into fragments. Little detachments gathered by the roadside, after crossing the bridge, crying out the numbers of their regiments as a guide to scattered comrades. And what a night it was! Dark, gloomy, and beclouded by the volumes of smoke which had risen from the battle-field.”

Had Longstreet pushed rifled guns to the front, upon the turnpike, and fired at high elevations down its straight course, he might have landed shells in this retreating column as far as the Stone Bridge. This would probably have blocked the column and added much to the captured property. But the Confederates as yet had no artillery organization which could quickly appreciate and improve all the passing opportunities of a battle-field. Indeed, as before stated, the army was only a mass of divisions, associated by temporary assignments to Longstreet and Jackson, who were themselves only division commanders.

On the morning of the 31st, Lee lost no time in renewing his advance. As the position at Centreville was strong, and had been fortified by the Confederates in 1861, he ordered Jackson’s corps to turn Centreville, crossing Bull Run at Sudley, and moving by the Little River turnpike upon Fairfax C. H. Stuart’s cavalry were to precede Jackson. Longstreet was to glean the battle-field and then to follow Jackson. All progress was slow on account of the rain and mud. This was the third battle within 14 months which had been closely followed by heavy rain,—Bull Run, Malvern Hill, and Second Manassas. The theory took root that cannonading has rain-making virtue.

On the 31st Jackson, over wretched roads and through continued rain, advanced only about 10 miles, and bivouacked at Pleasant Valley on the Little River pike. Longstreet’s advance reached Sudley Ford, and the care of the battle-field was left to the reinforcements from Richmond, which were now coming up. On Sept. 1, the march was resumed by Jackson at an early hour, and Longstreet followed over the same road. Pope, in a despatch to Halleck during the night, had reported his falling back to Centreville, but had still claimed a victory, saying: “The enemy is badly whipped and we shall do well enough. Do not be uneasy. We will hold our own here.” Yet he had left 30 guns and 2000 wounded on the battle-field, and had ordered Banks at Bristoe Station, in charge of his trains, to destroy all supplies and to come to join him at Centreville, with his troops, by a night march. With Franklin’s, Banks’s, and Sumner’s corps, which arrived early on the 31st, he had now 30,000 fresh men, but his delay at Centreville was limited to a single day. That evening the presence of Stuart’s cavalry, shelling his trains near Fairfax C. H., became known, and next morning reports reached him of Jackson’s corps on the Little River turnpike.

Finding his position again turned, Centreville was abandoned, and a new one ordered to be taken at Fairfax C. H. This move practically placed him beyond pursuit. His whole army was now united, and too close to its fortified lines to be again flanked out of position. And, although there was demoralization in some organizations, yet there were many excellent division and brigade commanders, leading veteran troops so well trained and disciplined that their fighting was of the highest type. An illustration of this took place late in the afternoon of the 1st. Jackson’s corps, approaching the junction of the Little River and Warrenton pikes, had formed line of battle at Ox Hill, with A. P. Hill’s division upon the right. Two of Hill’s brigades, under Branch and Brockenbrough, were sent forward to develop the enemy, who were known to be near. A terrific thunder storm, with strong wind and blinding rain directly in their faces, came on just as this advance was being made. With this storm on their backs, Stevens’s division of Reno’s corps, the 9th, charged the approaching Confederates in front and flank, and drove them back in much confusion. The division making the charge had been engaged on both the 29th and 30th, and had been defeated on both days. Its fine behavior and hard fighting was the feature which makes this engagement notable. It was, under the circumstances, a useless affair. There was little chance of either side accomplishing any result beyond the killing of a few opponents, with probably equal loss to itself. Hill sent strong reinforcements to restore his battle, and Kearny’s division of the 3d corps came to Stevens’s assistance. Stevens was shot through the head. Kearny, riding into the Confederate lines in the dusk, was also shot dead, as he tried to escape capture by wheeling his horse and dashing off, leaning behind his horse’s neck. The fighting on both sides was desperate and bloody, but the Federals were driven back. During the night, the whole Federal army was withdrawn from the vicinity of Fairfax, and took refuge within the fortified lines about Alexandria.

Stevens and Kearny were both prominent and distinguished officers. The advantage to the Confederates of their being taken off, like the cashiering of Fitz-John Porter, was among the few fruits of their victory. Indeed, at the moment when Stevens fell, bearing the colors of a regiment which he had taken from the hands of a dying color-bearer, the authorities in Washington were about to supersede Pope, and place Stevens in command of the now united armies of Pope and McClellan. He had graduated at the head of Halleck’s class at West Point in 1839, and Halleck was well acquainted with his military attainments. Both Stevens and Kearny were favorites in the old army, had served most creditably in Mexico, and both had been severely wounded in the capture of the city, Kearny losing his left arm. Kearny’s body fell into the hands of the Confederates, and being recognized, it had been sent the next day, under a flag of truce, by Lee, into the Federal lines with a note to Pope, saying:—

“The body of Gen. Philip Kearny was brought from the field last night, and he was reported dead. I send it forward under a flag of truce, thinking the possession of his remains may be a consolation to his family.”

This affair ended the battle. On the morning of Sept. 2 it was apparent that the enemy had escaped, and Lee allowed his whole army to be in camp and have a little much-needed rest. While he had fallen short of destroying his greatly superior adversaries, he could yet look back with pride upon the record he had made within the 90 days since taking command on June 1. He had had the use of about 85,000 men, and the enemy had had the use, in all, of fully 200,000.

At the beginning, the enemy had been within six miles of Richmond. He was now driven within the fortifications of Washington, with a loss in the two campaigns of about 33,000 men, 82 guns, and 58,000 small-arms. Lee’s own losses had been about 31,000 men and two guns.

The critics who had declared that he would never fight were forever silenced and pilloried in shame. In the last affair at Ox Hill, on Sept. 1, the casualties in A. P. Hill’s corps were 39 killed and 267 wounded, and in Ewell’s were 44 killed and 156 wounded, a total of 83 killed and 423 wounded; 506 total. There were no reports in the Federal army of this particular affair, but probably the losses were not very unequal.

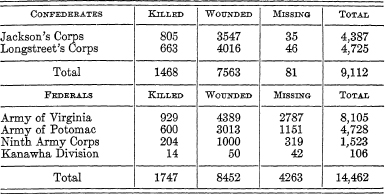

The losses of the two armies for the whole campaign are summarized as follows. No report was made of casualties in the Confederate cavalry, which were probably about 100.

Thirty guns and over 20,000 small-arms were collected from the field.

My own share in this campaign was limited to keeping up the supply of the ammunition consumed. I had the satisfaction of seeing the organization and working of my department stand well the test of a severe campaign, and a considerable separation from its depots. Both in the artillery and infantry, the fighting was incessant and severe, but the supply of ammunition never failed, and, at the close of the campaign, without a day’s delay, the army was prepared to undertake an even more distant and desperate adventure. When Lee moved from Gordonsville to cross the Rapidan, I was ordered to follow with my reserve ordnance train from near Richmond. I followed as rapidly as possible, but could not overtake the army until after Chantilly. Then I replenished all expenditures, so that the troops advanced into Maryland with everything full.

Thereafter I kept myself and train in close proximity to Lee’s headquarters in all the movements, and, with my wagons running between our successive positions and Staunton, Va., we were able to meet all demands.

1 S. J. II.. 124..