FALL OF 1862

Political Situation. Lincoln orders Advance. A Confederate Raid. Lincoln Dissatisfied. Condition of Confederates. Reorganization. Lee moves to Culpeper. McClellan succeeded by Burnside. Plan of Campaign Changed. Burnside’s Strength. Lee’s Strength. Sumner at Falmouth. Non-arrival of Pontoons. Surrender Demanded. Earthworks Erected. Jackson Arrives. Burnside’s Plan. Marye’s Hill. Building the Bridges. The Bombardment. The Crossing Made. Dec. 12. The Plan Changed. Jackson’s Line. Franklin Advances. Gibbon supports Meade. Meade strikes Gregg. The Counter-stroke. Jackson’s Proposed Attack. Casualties. On the Federal Right. The Formations. French and Hancock Charge. Howard Charges. Sturgis Charges. Sunken Road reinforced. Griffin’s Charge. Humphreys’s First Charge. Humphreys’s Second Charge. Humphreys’s Report. Tyler’s Report. Getty’s Charge. Hawkins’s Account. A Federal Conference. Dec. 14, Sharp-shooting. Dec. 15, Burnside Retreats. Flag of Truce. Casualties. New Plans. The Mud March. Burnside Relieved.

AFTER the battle of Sharpsburg, rest, reorganization, and supplies were badly needed by both armies, and, as the initiative was now McClellan’s, he determined not to move until he was thoroughly prepared. Lincoln had two months before drawn up his Emancipation Proclamation and was waiting for a victory to produce a favorable state of feeling for its issuance. Sharpsburg was now claimed as a victory, and, on Sept. 22, the Proclamation was issued, freeing all slaves in any State which should be in rebellion on the coming Jan. 1. This was supposed to be a war measure, though nothing could have been more void of effect than it proved. McClellan did not approve of the Proclamation, and he let his sentiments on the subject be known, although he issued a very proper order to the army, deprecating political discussion. His attitude, however, alienated him from the administration, and the party in power in Washington.

A few days after the battle, Lincoln had visited the army, and, on parting from McClellan, had expressed himself as entirely satisfied, and had told McClellan that he should not be forced to advance until he was ready. But when two weeks had passed, during which great quantities of supplies of all kinds were rushed to the army by every channel, McClellan on Oct. 7 received instructions to “cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy, or drive him south. The army must move now while the roads are good.”

On receipt of this, McClellan conferred with his chief quartermaster, who thought that sufficient supplies would be on hand within three days. Meanwhile, on Oct. 10 a fresh trouble arose. Stuart with 1800 cavalry and Pelham’s battery had been sent by Lee upon a raid. Fording the Potomac, some 15 miles above Williamsport, at dawn on the 10th, by dark Stuart reached Chambersburg, where he burned a machine-shop, many loaded cars, and a supply depot, paroled 285 sick and wounded Federals, and gathered about 500 horses. Next morning he moved to Emmitsburg, and thence below the mouth of the Monocacy, where he recrossed the Potomac, on the forenoon of the 12th. The distance travelled had been 126 miles, of which the last 80 from Chambersburg were accomplished without a halt.

An epidemic of foot-and-mouth disease was prevailing at this time among the enemy’s cavalry,1 and the desperate efforts to intercept Stuart, made with reduced forces, put much of it out of condition for active service until they could get some rest and several thousand fresh horses. Pleasanton had made a march of 55 miles in 24 hours, part of the distance across the mountains by very bad roads, and Averill’s brigade had travelled 200 miles in four days. Stuart’s loss was but one man wounded, and his conduct of the expedition was excellent. Yet the raid risked a great deal in proportion to the results accomplished. It might easily have happened that the whole command should be captured. But the incident contributed largely to McClellan’s delay, and to the growing dissatisfaction of the government with his conduct.2

Mr. Lincoln had allowed McClellan to decide whether his advance should be up the Shenandoah Valley, or east of the Blue Ridge, but expressed a preference for the latter route.

McClellan, however, had decided to take the Valley route, for fear of Lee’s advancing into Md. and Pa. if it was left uncovered. Both Lincoln and Halleck thought his fears groundless and his caution excessive. Neither of them believed the Confederate army to be as immense as McClellan reported, and both knew that if the Federals needed supplies the Confederates needed them much more. In Lincoln’s practical style, he often made pertinent suggestions to McClellan and would sometimes mingle with them a touch of sarcasm. He wrote that if Lee “should cut in between the Army of the Potomac and Washington, McClellan would have nothing to do but to attack him in the rear.” Soon after Stuart’s raid, he suggested that “if the enemy had more occupation south of the river, his cavalry would not be so likely to make raids north of it.” And on Oct. 25, he telegraphed McClellan in reply to a despatch about sore-tongued and fatigued horses, “Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done, since the battle of Antietam, that fatigues anything?”

On Oct. 26, McClellan put his army in motion, 19 days after his receipt of the President’s order. By this time he was willing to adopt the line of advance east of the Blue Ridge, as the stage of water in the Potomac River now made all fords impracticable. The crossing was made at Berlin, about 10 miles below Harper’s Ferry. Pontoon bridges were laid, and the army crossed over rather leisurely, the last of it, Franklin’s corps, on Nov. 1 and 2.

We will now return to the Confederates, who, since Sharpsburg, have been resting and recuperating between Winchester and Bunker Hill.

Our base of supplies was now Staunton, more than 100 miles distant, but over fairly good roads. Our trains were actively at work, bringing ammunition, food, and clothing, and gradually our condition approached the normal. But the supply, even of wagons, was limited, and, as late as Oct. 20, 55 were wanted for the reserve ordnance train of Longstreet’s corps, and 41 for that of Jackson.

Meanwhile, as important as reequipment, a thorough reorganization took place, and at last we became an army rather than a collection of brigades, divisions, and batteries. In Oct. Longstreet and Jackson were made lieutenant-generals, and major-generals and brigadiers were promoted and our 1st and 2d army corps were formed, following the example of the Federals nearly a year before.

The formation of our batteries into battalions was also carried forward, but rather slowly. A large proportion of our guns were but 6-Pr. and 12-Pr. howitzers, which the enemy had now discarded as too light. There are no returns showing our different varieties of small-arms, but that we still had men armed with flintlocks is shown by the return of 13 picked up on the field after the battle of Fredericksburg.

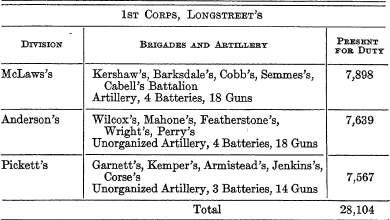

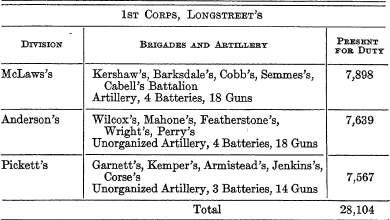

The organization, when completed, stood as follows, the strength being given from the returns of Nov. 20, 1862.

ORGANIZATION OF ARMY OF NORTHERN VA., NOV., 1862

On Oct. 27 Lee moved with Longstreet’s corps and Pendleton’s reserve arty. toward the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge. My reserve ordnance train moved on the 29th via Nineveh, Front Royal, Chester Gap, Gaines’s Cross-roads and Sperryville, and encamped at Culpeper on Nov. 4. Lee, in person, had already arrived there. A few days after I was placed in command of the battalion of artillery which had been commanded by Col. S. D. Lee, who was now promoted brigadier-general and sent to Vicksburg. My successor as chief of ordnance was Col. Briscoe G. Baldwin, who served with great success until the surrender at Appomattox.

Meanwhile, an important event was on foot. We have seen the lack of cordiality between McClellan and the President, and the growth of mistrust of the latter’s intention to prosecute the active offensive campaign desired. On Oct. 27 he had telegraphed the President urging the necessity of filling the old regiments with drafted men “before taking them into action again.” The tone of his letters had long been unsatisfactory, and this expression kindled into flame the growing suspicion that he was simply preparing new excuses for delay. Immediately on reading the message Lincoln showed himself ready to meet the issue by wiring back:—

Now I ask a distinct answer to the question, “Is it your purpose not to go into action again until the men now being drafted in the States are incorporated into the old regiments?”

McClellan read between the lines the threat conveyed, and backed squarely down. He promptly explained that the offensive despatch was the inadvertence of an aid, and promised to “push forward as rapidly as possible and endeavor to meet the enemy.” Indeed, the Confederates noted, during the next week, the unwonted vigor of his advance. There were constant sharp skirmishes, and the enemy got possession of the two lower gaps in the Blue Ridge, Snicker’s and Ashby’s, and held the outlet of Manassas Gap. McClellan’s headquarters were advanced to Rectortown. His cavalry occupied Warrenton, and it was evident that he would soon cross the Rappahannock. Then, suddenly, his activity ceased, and from Nov. 9 to the 17th, the Federal army laid quietly in its camps. His backdown had come too late. He had been removed from the command on Nov. 7, and Burnside substituted in his place.

McClellan’s promises of Oct. 27 might have satisfied President Lincoln, but there were strong influences now determined upon a change, and which wanted not only the head of McClellan, but that of Porter. On Nov. 5 the President wrote an order authorizing Halleck, in his own discretion, to relieve McClellan, and to place Burnside in command of the army. Porter was also to be relieved from the command of the 5th corps, and to be succeeded by Hooker.

On the same date these formal orders were prepared and signed by Halleck, but they were not promulgated for two days.

The designation of Burnside to succeed McClellan was a great surprise to old army circles, both in the Federal and Confederate armies; and was, perhaps, an unpleasant one to Burnside himself. He was popular, but not greatly esteemed as a general. He had commanded a brigade at the first battle of Bull Run, but had in no way risen above, even if he reached, the average of the brigade commanders. He had later had the luck to command the expedition to the N.C. Sounds, where his overwhelming force easily overcame the slight resistance that it met. This gained him the prestige, in newspapers and political circles, of successful independent command. As commander of a corps, he was one of the four next in line for promotion—Burnside, Hooker, Sumner, and Franklin.

The older officers dreaded Hooker’s appointment. By many he was thought utterly unfit, though a brave man and a hard fighter. Moved by the wishes of his friends, Burnside was brought to accept the command rather than see it go to Hooker.

McClellan was not unprepared for the blow, and he met it gracefully and did all in his power to commend his successor to the confidence of the army. He had not, however, anticipated that he was to be relegated to private life, but had supposed that he would be transferred to some command in the West. But no other command was ever offered him. A few days later Burnside submitted to the President his plan for the campaign, and it was approved, though reluctantly. McClellan’s plan had been to interpose between Lee’s divided forces. Already he was not far from such a position. From Longstreet’s corps to Jackson’s was over 40 miles by the roads across the mountains, and McClellan’s forces were within 20 miles of either. But Lee could have delayed a march upon either, and, by falling back, might unite his two corps, behind the Robertson River, before accepting battle.

This had been Lee’s plan, if the threat of Jackson’s position upon the Federal flank should fail to prevent their advance.

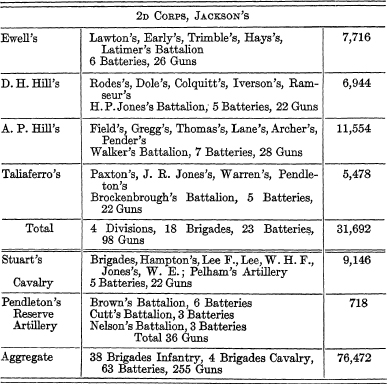

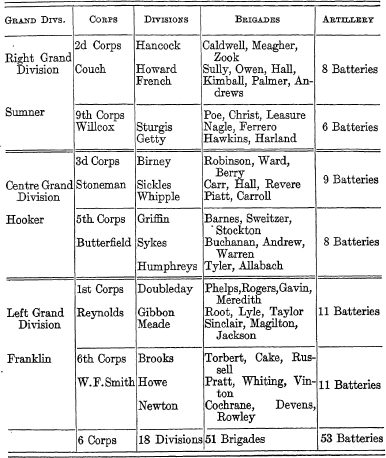

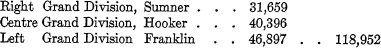

Burnside’s organization was as follows:—

Burnside began his campaign with a blunder. He adopted Richmond as his objective, instead of Lee’s army. The latter was within a day’s march of him, and its wings were separated by two days’ march. Here was an opportunity for a skilful commander, but Burnside decided to make Fredericksburg a base, and to move thence upon Richmond. On Nov. 15, he turned his back upon Lee and marched for Fredericksburg. Meanwhile, he had made some important changes in his organization, by the formation of three grand divisions out of his six corps in order to lessen the routine duties of his office.1

Besides the troops shown above, the right grand division comprised two brigades of cavalry and a battery, and each of the others, one brigade of cavalry and a battery. There was also an artillery reserve of 12 batteries, an engineer brigade with the pontoon train, and an escort and a provost guard of infantry and cavalry.

On Dec. 10, the return of the army showed “present for duty,” as follows:—

The Artillery comprised 374 guns.

Besides these troops there were two corps, the 11th, with 15,562 present for duty, under Sigel; and the 12th, with 12,162, under Slocum, which Burnside called his reserve grand division. These troops, under command of Sigel, were on the march to Fredericksburg, but they did not arrive until after the battle.

Besides these, there were 51,970 holding the line of the Potomac above Washington, and the fortified lines about the city and Alexandria, with 284 guns of position, and 120 field-pieces. Thus, all together, there were available for use against Lee and to protect the capital, 198,546 men and about 900 guns.

On the same day, Dec. 10, Lee’s return showed his present for duty, by divisions, as follows:—

Adding Pendleton’s reserve artillery, 718, Stuart’s cavalry, 9146, and 41 general staff, we have Lee’s aggregate, 78,483, and about 250 guns. This was practically the largest army which Lee ever had in the field. Possibly, during the Seven Days, more troops were near Richmond, but, being organized only in divisions, or in independent brigades and batteries, and thus less easy to handle, they constituted a much less powerful army.

As before stated, on Nov. 15, Burnside commenced his movement upon Fredericksburg, Sumner’s grand division leading the way. Already his cavalry had made reconnoissances which had attracted attention, and Lee, on the 15th, had sent a regiment of cavalry, one of infantry, and a battery to reinforce four companies of infantry and a battery already at Fredericksburg. Orders were also sent to destroy the railroad from Fredericksburg to Acquia Creek. On the 17th it was learned that gunboats and transports had entered Acquia Creek, on which W. H. F. Lee’s brigade of cavalry was despatched in that direction, and Stuart was ordered to force a crossing of the Rappahannock and reconnoitre toward Warrenton. This was done on the 18th, and the enemy’s general movement was discovered. A part of Longstreet’s corps was put in motion on the 18th, and the remainder followed next day.

Sumner’s corps arrived at Falmouth on the 17th, and an artillery duel ensued, across the river, rashly provoked by the Confederates, who had orders to oppose any force attempting to cross. It really came near inducing the enemy to cross, though under orders from Burnside not to do so. For under the superior metal of the Federals, the Confederate gunners were driven from their guns. There was a ford in the vicinity, and the temptation was strong to come over for them, but the existence of orders prevented its being done.

For Burnside had feared that Lee would overwhelm any small force which should cross before he was prepared to support it. Lincoln and Halleck, indeed, had only consented to the movement via Fredericksburg with the understanding that the army should possess itself of the heights opposite the town by crossing the river above and coming down. Burnside had deliberately changed this plan, after starting on the march. After the battle, his personal responsibility for the changed result was brought home to him unpleasantly.

Swinton asserts that Burnside—

“did not favor operating against Richmond by the overland route, but had his mind turned toward a repetition of McClellan’s movement to the Peninsula; and in determining to march to Fredericksburg he cherished the hope of being able to winter there upon an easy base of supplies, and in the spring embarking his army for the James River.”

The three weeks’ delay between his arrival and his crossing the river suggests the lack of definite plans. At first the delay was attributed to the non-arrival of pontoon trains. These trains had been ordered on Nov. 6 from Rectortown to Washington City. This order failed to reach Berlin until the 12th.

Sumner was anxious to cross, and asked Burnside if he might do so without waiting for pontoons, “if he could find a ford.” He had found the ford before he made the request, but Burnside’s inclinations were adverse to a battle and he could not be beguiled.

So the small Confederate force held the town until the 20th, when Longstreet arrived with McLaws’s division, and was followed the next day by the remainder of the corps.

On the 21st Sumner sent a formal demand for the surrender of the town, basing it upon the statement that his troops had been fired upon from under cover of the houses, and that mills and manufactories in the town were furnishing provisions and clothing to the enemy. He demanded an answer by 5 P.M., and said that if the surrender was not immediate at nine next morning, he would shell the town, the intermediate 16 hours being allowed for the removal of women and children.

This note, only received by the Mayor at 4.40 P.M., was referred to Longstreet, who authorized a reply to be made that the city would not be used for the purposes complained of, but that the Federals could only occupy the town by force of arms. Mayor Slaughter pointed out that the civil authorities had not been responsible for the firing which had been done, and, further, that during the night it would be impossible to remove the noncombatants. During the night Sumner sent word that in consideration of the pledges made, and, in view of the short time remaining for the removal of women and children, the batteries would not open as had been proposed.

But the letter left it to be inferred that the purpose to shell was only postponed, and Lee, who had now arrived, advised the citizens to vacate the town. This advice was followed by the greater part of the population. It was pitiable to see the refugees endeavoring to remove their possessions and encamping in the woods and fields, for miles around, during the unusually cold weather which soon followed.

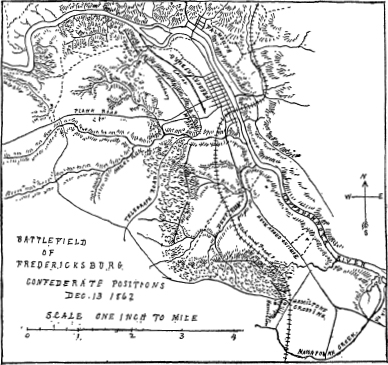

This incident is responsible for the existence of most of the earthworks, which, at the time of the battle, contributed largely to the repulse of the enemy’s assaults upon Marye’s Hill. Great sympathy, of course, was felt for the citizens, and Lee, immediately after his arrival, ordered batteries to be erected, from which the enemy’s positions, upon the hills commanding the town from the north, could be replied to by our rifled guns, in case of their shelling the town. Lee at first had not intended to give battle at Fredericksburg, but had proposed after delaying the enemy to fall back behind the North Anna River, and to deliver his battle there. Both he and Jackson objected to the position at Fredericksburg that the river, with the commanding positions on the north bank, could always afford a safe retreat to a beaten enemy, as the Antietam had done at Sharpsburg. This was undoubtedly true, as was soon afterward proved when the battle took place. At the North Anna the enemy, if defeated, might be successfully pursued and some fruits of victory be gathered.

But the position at Fredericksburg soon began to show its good points, and as the country behind the Rappahannock was able to supply some subsistence which would otherwise be lost, it was decided to give battle at Fredericksburg, against Jackson’s protest.

Burnside’s pontoons arrived on Nov. 25. By this time a few earthworks showed upon the Confederate hills, and led him to delay, and to reconnoitre the river for a flank movement. Above Fredericksburg the country was hilly and wooded. The river was narrow, and there were several fords. These features would have made a crossing easy to accomplish by a surprise. Below the town the river widened, and the country opened. Yet Burnside adopted that flank for his movement, and began his preparations to cross at Skinker’s Neck, 12 miles below Fredericksburg, where the river was over 1000 feet wide.

Lee discovered his preparations, and as Jackson’s corps had arrived from the Valley about Nov. 29, it was moved to the right, and observed the river as far as Port Royal, 18 miles below. Jackson had not left Winchester until Nov. 22, five days after Sumner’s arrival at Falmouth. His troops had marched 150 miles in 10 days, but Lee and Jackson had both presumed largely on Burnside’s want of enterprise in allowing, for even a few days, 150 miles to separate the two corps. Lee had given no express orders to Jackson, but as late as Nov. 19, had written him to remain in the Valley as long as his presence embarrassed the enemy, hut to keep in view that the two corps must be united in order to give battle.

The Federal army was supplied with balloons. McClellan had used them on the Peninsula, but during Pope’s campaign, and in Md., they had not been seen, although the open character of the country would have often exposed and embarrassed the most important movements of the Confederates, had balloonists been on the lookout. Now, the balloons reconnoitring the country about Skinker’s Neck, discovered Jackson’s camps, and Burnside knew that his designs were disclosed. The discovery suggested an alternate piece of strategy. If he could cross at Fredericksburg, and rapidly push a force around Lee’s right at Hamilton’s Crossing, he might interpose between the forces about Skinker’s Neck and those in front of Fredericksburg. The pressure upon him to fight was great, and on Dec. 10 the orders were issued for a crossing that night. The programme was as follows:—

Two bridges were to be thrown across the river at the upper end of the town, one bridge at the lower end, and two about a mile below the town. Where the bridges were in pairs, one was for the use of artillery and one for infantry. The pontoon trains were to arrive opposite the chosen sites at 3 A.M., and unload the boats and material. By daylight this was to be finished and the boats placed in the river. The bridges were then to be built in from two to three hours. In length they would be from 400 to 440 feet. The weather was unusually cold, the thermometer being 24 degrees above zero. The ice in the river was about an inch thick. The bridges would be concealed from Confederate fire by the town. On the north bank, 179 Federal guns were put in position during the night, to cover the crossing, and it was believed that they could instantly silence any musketry fire from the opposite bank.

There had been ample time for the construction of formidable earthworks and abattis, had Lee originally intended to receive battle there. Probably 30 pits had been made, each for a single gun, but in few places had any protection for infantry been provided, except upon the river bank in front of the town. This portion of the line was under charge of McLaws, who had carefully located every sharp-shooter with reference to his protection and his communications. Elsewhere there was little preparation of any sort.

There was, however, one natural feature which proved of great value. The Confederate line occupied a range of low hills nearly parallel to the river and a few hundred yards back from the town. The Telegraph road, sunken from three to five feet below the surface, skirted the bottom of these hills for about 800 yards, until it reached the valley of Hazel Run, into which it turned. This sunken road was made part of the line of battle for McLaws’s infantry. It not only formed a parapet invisible to the enemy until its defenders rose to fire over it, but it afforded ample space for several ranks to load and fire, and still have room behind them for free communication along the line. In easy canister range, nine guns on the hills above could fire over the heads of the infantry. This position was known as Marye’s Hill.

The crossing had been expected for some days, and orders given for two signal guns, whenever it was attempted. On the 10th Burnside’s army was ordered to cook three days’ rations, and the news was quickly conveyed to Lee, being shouted across the river to one of our pickets. At 2 A.M., the pickets reported that pontoon trains could be heard on the opposite bank, and at 4.30 A.M. the building of the bridges commenced. The signal guns were fired about 5 A.M., and the different brigades and batteries, already alert, quickly took positions in the early dawn. The day was calm and clear except for a peculiar smoky haze or dry fog which now prevailed in the forenoons for several days. In the early hours it limited vision to a range of scarcely 100 yards, but, as the sun rose higher, it faded and disappeared by noon.

The sharp-shooters along the river front had reserved their fire until after the discharge of the signal guns. They then opened upon the bridge builders, who could now be dimly seen, and soon drove them off the bridges with some loss. A heavy fire of infantry and artillery was opened in reply, upon the Confederate rifle-pits, under which they became silent. After a half-hour’s fire, the bridge builders made a fresh attempt; but their appearance provoked fresh volleys from Barksdale, whose brigade was holding the city, and again the bridges were cleared. Several efforts of this sort were made during the morning, all resulting similarly, and the casualties in the Engineer brigade, which had the work in charge, ran up to near 50.

At the site selected for Franklin’s crossing about a mile below the city, there was no opposition, for there was no shelter for even a Confederate skirmish-line. The bridges here were finished by 11 A.M. Franklin, however, was ordered not to cross until the resistance at the town had been overcome. Here, by 11 A.M., the Engineer brigade had abandoned the task of building bridges under fire. When this state of affairs was reported to Burnside, he ordered every gun in range of the city to fire 50 rounds into it. Probably 100 guns responded, and the spectacle which was now presented from the Confederate hilltops was one of the most magnificent and impressive in the whole course of the war.

The city, except its steeples, was still veiled in the mist which had settled in the valleys. Above it and in it incessantly showed the round white clouds of bursting shells, and out of its midst there soon rose three or four columns of dense black smoke from houses set on fire by the explosions. The atmosphere was so perfectly calm and still that the smoke rose vertically in great pillars for several hundred feet before spreading outward in black sheets. The opposite bank of the river, for two miles to the right and left, was crowned at frequent intervals with blazing batteries, canopied in clouds of white smoke.

Beyond these, the dark blue masses of over 100,000 infantry in compact columns, and numberless parks of white-topped wagons and ambulances massed in orderly ranks, all awaited the completion of the bridges. The earth shook with the thunder of the guns, and, high above all, a thousand feet in the air, hung two immense balloons. The scene gave impressive ideas of the disciplined power of a great army, and of the vast resources of the nation which had sent it forth.

Under cover of this storm of shell, the Federal bridge builders again ventured upon their bridges and tried to extend them, but the artillery fire had been at random into the town, and not carefully aimed at the locations of the sharp-shooters. Consequently, these had not been much affected, and presently the faint cracks of their rifles could be heard, between the reports of the guns. The contrast in sound was great, but the rifle fire was so effective that, again, the bridges were deserted. Indeed, the promiscuous fire of bombardments seldom accomplishes any result. Carnot, in his Defense of Strong Places, says that they “are resorted to when effective means are lacking.” No citizen was reported injured, though many left the town only after firing began in the morning, and some remained during the whole occupation by the Federals.

Presently Gen. Hunt, chief of artillery, suggested an expedient. There were 10 pontoon boats in the water along the north shore. On the southern shore the sharp-shooters, a little back from the high brink of the river, could only see the farther half of its width. Hunt proposed that troops should make a rush and fill the boats. These should then be rowed rapidly across to the shelter of the opposite shore, where the men could disembark under cover. A lodgment once made, other troops could follow, until a force was accumulated which could capture the rifle-pits.

This sensible course, which should have been the one first adopted in the morning, under cover of the fog, was now tried. Four regiments, the 7th Mich., the 19th and 20th Mass., and the 89th N.Y., volunteered for the crossing. The first boats suffered some casualties, but were soon safe under shelter of the bank. Other installments followed, and the Confederates, appreciating that their game was up, and that the bridges below the town were already available, began to withdraw. The pontoniers now returned to their work, and the bridges were completed. Some skirmishing took place in the streets, and a few were cut off and captured. But the defense had practically gained the entire day, for although a division of the 6th corps crossed in the afternoon, it was subsequently recalled, all but one brigade, left to guard the bridge-heads during the night.

This delay robbed Burnside’s strategy of its only merit. It had been his hope to find Lee’s army somewhat dispersed, as indeed it had been; D. H. Hill’s and Early’s divisions having been at Skinker’s Neck and Port Royal, 12 to 22 miles away. But they were recalled on the 12th and reached the field on the morning of the 13th after hard marching. The casualties suffered by the Confederates engaged in this defense were 224 killed and wounded and 105 missing. Of the Federal losses, separate reports were made only of the Engineer brigade, engaged upon the bridge work. This lost 50 killed and wounded, and Hancock reported the loss of 150 in two regiments which had supported the Engineers.

The night was quite cold, the thermometer falling to 26 degrees. While this is not extreme for this latitude and season, it caused great suffering among the troops from the South, generally thinly clad, and for some months far from railroad transportation. Especially was this the case on the picket-lines where fires were forbidden. Kershaw reported it “a night of such intense cold as to cause the death of one man, and to disable temporarily others.”

The whole of the 12th was occupied in crossing two grand divisions. Sumner crossed the 2d and the 9th corps by the upper bridges and occupied the town. Franklin crossed the 1st and 6th corps by the lower bridges and occupied the plain as far out as the Bowling Green road, a half mile from the river, and the same distance in front of the wooded range of hills occupied by Jackson’s corps. Much has been said of the strength of the Confederate position upon the hills overlooking the plateau of the valley, with its sunken road in front of Marye’s Hill. The Federal position was even a stronger one, against any attack by the Confederates. The dominating hills and plateaus of the north bank, with its concave bend at Falmouth and unlimited positions for artillery, protected by the wet ditch, as it were, of the river in front, practically constituted a fortress, with the plains of the south bank as its glacis. The Bowling Green road, along their middle, running between high banks on each side, made a powerful advanced work, and the low bluffs near the river made a second line. The Confederate line, also concave in its general shape and dominating the plains between, was strong against assaults in front, but neither flank was secure against being turned. Its right especially was in the air at Hamilton’s Crossing, and Burnside planned to attack this flank.

Franklin’s grand division had been strengthened for that purpose by three divisions assigned to his support. One of them, Burns’s, of the 9th corps, was already across the Rappahannock and on the left of Sumner, separated from Franklin’s right only by Deep Run, across which bridges had been laid. The other two were Sickles’s and Birney’s divisions of the 3d corps, of Hooker’s grand division, which was still upon the north side, but close to the bridges, in readiness to cross. With these troops, Franklin had nearly 60,000 men. During the afternoon of the 12th, Franklin had urged that these two divisions should be brought over during the night, and that preparations should be made for an advance at daylight. Burnside promised to order it, but the order was not given until the next morning.

He apparently lacked confidence in himself and shrank back from his own plans as the moment of execution drew near. Franklin had been informed that Burnside would give the final order which should put his force in motion. About 7 A.M. on the 13th an order came, but it was not at all the order expected. It made no reference to the plans of the day before, but ordered Franklin to “keep his whole command in position for a rapid movement down the old Richmond road.” Then he was to “send out, at once, a division, at least, to seize, if possible, the height near Capt. Hamilton’s on this side of the Massaponax, taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.”

The order went on to tell Franklin what Sumner was to be doing at the same time. He was also to send “a division or more up the Plank road to its intersection with the Telegraph road, where they will divide with the view of seizing the heights on both of these roads.” Then the order set forth what he hoped to accomplish. “Holding these two heights, he hopes will compel the enemy to evacuate the whole ridge between them.” It is enough to say that this change from a single attack with full force upon our right, to two weak and isolated attacks on the right and left, lost the battle. Being ordered to send “at least a division,” Franklin designated the 1st corps under Reynolds for the attack upon the height at Hamilton’s Crossing. Meade’s division was to lead, closely followed and supported by Gibbon; Doubleday’s was to protect the left flank of the advance, which was threatened by Stuart’s artillery. Franklin would have also sent a portion of the 6th corps, but it had been placed in position for the attack first planned, and time would have been lost by a change.

The Confederate right flank was not well prepared to stand the coming shock in view of the long warning it had had. The fact was that Jackson’s troops had been in observation of the river below, and had only arrived upon the field on the 12th. Previously this flank had been held only by Hood’s division, and during its stay, little probability of attack had been foreseen. Consequently, Hood made but two works of preparation. On the edge of the woods, overlooking the railroad, a trench had been dug long enough to hold a brigade and a half; and through the thick wood 500 yards in the rear, a road had been cleared, affording communication behind the general line which occupied the wooded hills.

On the 12th A. P. Hill was placed in front, to cover about a mile and a half of line with his six brigades. On the extreme right he posted 14 guns, and supported them with half of Brockenbrough’s brigade. No other position for artillery offered along the front until the left of the division was reached. Here 12 guns were advanced north of the railroad, and 21 more were placed upon a low, open hill, south of the road some 200 yards to the left and rear, supported by Pender’s brigade. The wooded hills between these positions were held by the four remaining brigades, but no two of them connected with each other. On the right, the other half of Brockenbrough’s and Archer’s brigade occupied the trenches which had been built by Hood. Archer’s left rested on a swampy portion of the wood overgrown with underbrush, and it had carelessly been assumed to be impassable. Maj. Yon Borcke, a German officer on Stuart’s staff, had suggested felling it, but it was not thought worth while. On the far side of this swamp, Lane’s brigade took up the line; the gap between it and Archer’s being about 500 yards.

Beyond Lane was another considerable gap to his left and rear, where Pender’s brigade was supporting the 12 and 21 guns before referred to. Behind Lane, about 400 yards, was Thomas’s brigade. The remaining brigade of the division, Gregg’s, was placed in the military road opposite the swamp and gap between Archer and Lane.

If we call this disposition of Hill’s troops one of two lines, a third line was formed by the divisions of Early and Taliaferro—Early on the right—a short distance in rear, and a fourth one by the division of D. H. Hill in rear of that. Burnside was losing one of the advantages of his superior force by concentrating it upon too short a front. He was hemmed in on the left by Massaponax Creek, and was confined to a front attack. With only a mile and a half to defend and with about 30,000 infantry in hand, covered by the woods from accurate artillery fire, Jackson was very strong. With this understanding of the positions and forces the result might have been predicted. The faulty disposition of A. P. Hill’s division, with two gaps in his front line, would surely allow to the enemy a temporary success. But the strong reserves close at hand were enough to restore the battle, and even induce a counter-stroke. The counter-stroke, however, must be driven back with loss when it ventures out into the plain. With this foregone result of the game set forth, we may now briefly describe the moves by which it was played on the left, before taking up the independent battle to be fought out during the whole afternoon by the Federal right.

During the night of the 12th, the ground was frozen, and the movements of artillery could be plainly heard through the fog, even before dawn brought the music of bands and commands of officers all strangely muffled but clearly audible in the still air. We were now about to measure our strength with the largest and best-equipped army that had ever stood upon a battle-field in America. But our own army was better organized and stronger than ever before, and now, finding itself concentrated at exactly the right moment, it was as confident and elated as if the victory had already been won.

About 10 A.M., the gradual clearing of the mist began to reveal the plain, and the Federal skirmishers and guns began to feel for our positions. Our own guns took little or no part in this preliminary firing, saving themselves for the approach of the hostile infantry. This was not long delayed, Meade’s division of three brigades taking the lead, supported by Gibbon’s division, a little in rear on its right flank, and Doubleday’s on its left. Some delay ensued in their crossing the Bowling Green road, owing to the hedges and ditches lining it, which had to be made passable for the artillery, and here the Confederates first took the aggressive. From across the Massaponax “the gallant Pelham,” as he was called by Lee in his report to Richmond for the day, opened an enfilading fire upon the Federal lines with two guns which he had advanced within easy range. Meade replied with 12 guns, and one of Doubleday’s batteries assisted. Pelham frequently changed his position, but kept up his fire for nearly an hour until ordered by Jackson to withdraw, one gun having been disabled.

The advance was now resumed until within easy range, when a furious cannonade was opened upon the Confederate line, and maintained for nearly an hour. To this our guns made little reply, but both the artillery and infantry, concealed in the woods, suffered a good many casualties.

It was now about 11.30 A.M., and Meade’s infantry again advanced and were soon within 800 yards of the Confederate batteries. These opened with the 47 guns in position upon the two flanks, and eight more sent out from Pendleton’s reserve to Pelham. Under this fire the Federal advance was checked, and portions of the line, which received the brunt of it, were driven back. Meanwhile, fresh guns were added to the Federal line. The artillery duel raged for over an hour, when the Confederate fire ceased, the enemy’s infantry being no longer in sight, and the Confederate guns low in ammunition.

Upon this check, Gibbon’s division was sent to Meade’s support and formed in column of brigades on Meade’s right flank. Meade had two brigades in his front line, and his remaining brigade in a second line in close support. Doubleday’s division was moved up nearer behind Meade’s left, and engaged with Stuart’s skirmishers and artillery across the Massaponax. Birney’s and Newton’s divisions of the 3d and 6th corps were also sent forward to the Bowling Green road to support the attack, which Meade, at 1 P.M., was about to renew with Gibbon on his right. So the assault had a front of three brigades, and was three lines deep behind the right brigade; two lines deep behind the centre brigade, and only one line deep on the left.

The Confederate artillery fire at once reopened, but in weaker force than before, owing to its losses and expenditures, and the attacking forces were soon within musket range. Crashes of infantry now swelled the roar to the proportions of a great battle, mingling with a similar tumult which had now broken out in front of Fredericksburg. The battle was now on in its full force at two points, nearly five miles apart. Franklin’s part in it was of the shortest duration, and will be first told.

Gibbon’s division on Meade’s right overlapped the left flank of Lane’s brigade, and came in front of the 33 guns on A. P. Hill’s left. The 12 in advance had to be withdrawn to escape capture, but Gibbon’s three brigades were able to do no more than to fight their way up to the railroad with the loss of 1267 men; the two foremost brigades being successively broken and reinforced by the brigade following.

On Meade’s extreme left, his 3d brigade, under Gen. C. F. Jackson, found the artillery fire from the 14-gun battery on Hill’s right so effective that it abandoned the direct advance, and, inclining to the right, it moved behind Meade’s other brigades and took part in their fight, which has now to be described.

The marshy woods before referred to, which filled the wide gap between Archer and Lane, extended in a long triangle to the front across the railroad. The march of Meade’s division brought its right brigade into this wood, where the men found themselves free from the Confederate artillery fire. Not only were they hidden from view, but they were too far to the left for the guns on the right flank, and too far to the right for the guns on the left flank. It was this immunity from fire which brought C. F. Jackson’s brigade into the woods, and thus formed Meade’s division into a column of three brigades. This column, without firing a shot or meeting a picket, made its way entirely through the woods, until it fell upon Archer’s left flank and Lane’s right flank, turning each, and capturing about 300 prisoners. Archer’s men were so taken by surprise that some of his troops were caught with their arms stacked. Two regiments were quickly routed, and it was said that they were fired on as they retreated by their own comrades, who believed them to be deserting their posts without cause.

But the other regiments of Archer’s brigade held firmly, repulsing the enemy by the help of the troops on their right. Lane’s brigade, attacked in front by Gibbon’s division and its right flank turned by Meade’s through the unoccupied gap, was forced back in the woods, until Thomas’s brigade came to its support. This soon restored the line. Of Meade’s three brigades, the leading one was drawn into these separate fights upon each flank, while the second brigade continued to push forward. In this way it advanced unseen and unmolested for 500 yards, when it came upon the brigade of Gregg at rest in the so-called military road. Meade immediately opened a hot fire. Gregg could not realize that a Federal brigade could be so far within our lines. He rushed in front of Orr’s regiment, beating up the muskets of men who were firing and calling out that they were firing on friends, until he fell mortally wounded. This was the culmination of the Federal attack, and its collapse came quickly.

Orr’s regiment was broken, but the rest of the brigade stood firm, and changed front to meet the Federal advance. The latter were already in confusion when Lawton’s brigade came to reinforce Gregg, and the enemy was driven back rapidly. Hoke’s brigade was also sent to the assistance of Archer, and Early’s brigade to support Lane and Thomas. The whole Federal advance was driven from the woods and pursued out into the plain. The troops of Archer, Lane, and Thomas, or portions of them, joined in the counter-stroke, and the whole of both Meade’s and Gibbon’s divisions were involved and carried along with the retreat. But there was no adequate debauchment from the dense woods for rapid advance, and when the Confederates, disorganized by the pursuit, met the fresh troops of the enemy, the advance was checked, and, unpursued, it fell back to the line of the railroad. Indeed, the whole advance beyond the railroad had been unwise. Its only result would surely be the loss of the most daring of the pursuers. And the loss of such men from a brigade is like the loss of temper from a blade.1

The Federals made no further effort on their left during the day, and distant sharp-shooting, with intermittent artillery, was now the only activity until near sundown, which occurred about 4.45.

Burnside, at 1 P.M., had sent orders to Franklin to attack with the 6th corps on the right of Gibbon, and at 2 P.M. had repeated the order urgently and explicitly. But about this time Meade and Gibbon were driven back, and pursued, and put so completely out of action that fresh divisions had to replace them. When his left had been made secure, Franklin thought it too late to organize a fresh attack.

Jackson had noted within the Federal lines movements of troops and artillery with which they were preparing themselves to resist further attack. He had misinterpreted them, and supposed them to be preparations for a renewed assault. His appetite for battle had not been satisfied, and seeing the heavy force at the enemy’s disposal, he could not believe that they would be content with an affair of only two or three divisions. He accordingly waited to receive the expected assault, and finally, when it did not materialize, he determined to take the offensive himself. Apparently, he did not yet fully appreciate that the enemy’s position was practically a citadel. But he fortunately discovered it in time. While his assault was being prepared, he had indulged in some preliminary cannonading, which had put the enemy fully on the alert. In his official report, he writes:—

“In order to guard against disaster the infantry was to be preceded by artillery, and the movement postponed until later in the evening, so that, if compelled to retire, it would be under the cover of night. Owing to unexpected delays the movement could not be gotten ready until late in the evening. The first gun had hardly moved forward from the wood 100 yards when the enemy’s artillery reopened, and so completely swept our front as to satisfy me that the proposed movement should be abandoned.”

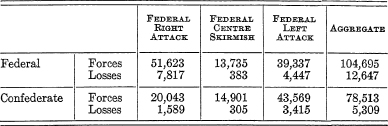

A. P. Hill’s division, which bore the brunt of the fighting on the 13th, out of 11,000, lost 2122 men. Early’s, which came to his support, lost 932 out of 7500. The other divisions lost less than 200 each, principally from the heavy artillery fire which the enemy threw into the woods. Meade’s division, out of 5000, lost 1853, and Gibbon lost 1267. So the casualties of the two fighting divisions on each side were nearly balanced; the Confederate loss being 3054 out of about 18,500 engaged, and the Federal, 3120 out of about 10,000 engaged.

We will now take up affairs at Fredericksburg. In his plans on the 12th, Burnside had not proposed a direct attack from the town, but on the 13th, as already told, had directed Sumner to prepare to assault Marye’s Hill with at least two divisions, but he was not to advance until Burnside gave the order. At first he proposed to give it only when Franklin had gotten possession of the hill at Hamilton’s Crossing; but about 10.30, becoming impatient, he delayed no longer.

The selection of the point of attack immediately opposite the town was perhaps influenced by the shelter afforded the troops within the town. But it was a fatal mistake. The most obvious, and the proper attack for the Federal right, was one turning the Confederate left along the very edge of the river above Falmouth, supported by artillery on the north bank which could enfilade and take in reverse the Confederate left flank. This attack is indicated by the concave north bank of the river, and it offered the easiest proposition to the Federals of the whole topography.

Sumner’s grand division numbered about 27,000 on the field. Hooker’s grand division had not yet been brought across the river, except the two divisions supporting Franklin. The other four (Whipple of the 3d corps, and Griffin, Sykes, and Humphreys of the 5th) were held near the upper bridges, and were all brought across during the day. They numbered about 26,000. Burnside’s position during the battle was at the Phillips house, on a commanding hill a mile north of the river. Lee made his headquarters on a hill, since called Lee’s Hill, overlooking Hazel Run and the eastern half of the field in front of the town. Two 30-Pr. Parrott rifles were located in pits on this hill, and were used with good effect upon the enemy advancing from the lower part of the town, until one exploded at its 39th round, and the other at its 54th.

Here Lee and Longstreet stood during most of the fighting, and it is told that, on one of the Federal repulses from Marye’s Hill, Lee put his hand upon Longstreet’s arm and said, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”

Sumner’s advance from the town began about noon. With skirmishers in front, French moved his brigades by parallel streets, and, crossing on bridges the little canal (about 20 feet wide and four feet deep) some 300 yards from the town, they formed successively for the attack in a considerable sheltered area, between the canal and the low bluff of a plateau which extended to the front some 400 to 500 yards from the sunken road at the foot of Marye’s Hill.

The three brigades of French formed in the order—Kimball, Andrews, Palmer. In close support came Hancock with Zook, Meagher, and Caldwell. Howard’s division was also brought out from the town as a further support. There was no special difficulty in coming from the town and getting under cover in the sheltered area above described, although it was done under fire of our artillery. The real trouble would lie in advancing about 400 yards across the plateau to the sunken road. There was no intervening abattis or ditch, but there were some small houses, gardens, and fences, affording some shelter, but breaking the continuity of the ranks. These two divisions numbered about 9000 men.

The front line of the Confederate defense was held by three Ga. regiments in the sunken Telegraph road, the 18th, 24th, and Philip’s legion of Cobb’s brigade. The 24th N.C. of Ransom’s held an infantry trench, which extended from the Telegraph to the Plank road.

On the crest of the hill above the road were four 12-Pr. guns, two 12-Pr. howitzers, and three 10-Pr. rifles, comprising the three batteries of the New Orleans Washington artillery under Col. Walton. On the left of the Plank road were four guns of Maurin’s battery, in pits, and, at Stansbury’s house, Parker’s battery of Alexander’s battalion, with four guns, found positions during the afternoon to fire upon the enemy’s right flank. His left flank was also partially exposed to the fire of the two Parrotts on Lee’s Hill. The infantry in the sunken road and ditch numbered at the commencement of the action only about 2000; but in support behind Marye’s Hill were about 7000 more, most of whom were brought into action later.

As each of the six brigades at short intervals was advanced over the crest of the plateau, it met the Confederate fire. Kimball’s brigade led, and no brigade during the day advanced farther, and but few as far. But he was wounded, and his brigade repulsed with a loss of 520 men within 20 minutes. Andrew’s brigade followed, and was likewise driven back with the loss of 342. Palmer, who came next, lost 291. The whole loss of the division (including its artillery which fired from the edge of the town) was 1160. About this time Ransom, seeing preparations for further attack, reinforced his line by Cooke’s brigade. The 27th. N.C. took position in the sunken road, and the 15th, 46th, and 48th occupied the crest of the hill, giving a second tier of infantry fire.

The remnants of French’s division, extending to right and left, took shelter in slight undulations and kept up fire both at the Confederate guns and infantry. Hancock’s division soon followed French’s and with a similar experience, but more prolonged and bloody. His leading brigade, Zook’s, lost 527. The second, Meagher’s, lost 545, and the third, Caldwell’s, lost 952. The loss of the division was 2032. The battle at this point had developed into a fearful example of successive attacks by small forces; the same vicious game which had lost 2d Manassas and Sharpsburg. But Burnside was now obstinate, and was ordering in fresh troops upon each of his two battle-fields. The turn of Howard’s division came next. He had been at first directed to attack upon his right of the Plank road, and was preparing to do so, when Hancock called for supports, and Howard was diverted to the same field. His leading brigade, Owen’s, did not push its assault so far as to be broken by the Confederate fire, but laid down where it could find a little cover. It was able here to hold its position until relieved after nightfall. His losses were 258. Howard’s second brigade was Hall’s, which was sent upon its charge somewhat to the right of the ground covered by the preceding charges. He was broken, rallied, charged again, and was again driven back, when he also found shelter, halted his command, and held on until night, having lost 515 men.

Howard’s third brigade was Sully’s, which was kept in reserve, and two regiments sent to reinforce Owens, and one to Hall. The losses in this brigade reached 122. Howard’s entire loss was 914. Couch’s whole corps had now been practically wrecked with a loss of 4114 men, in fighting eight separate battles with his nine brigades, against a force not half his size, all within four hours.

Next to the left of Couch’s corps was the 9th, under Willcox. Sturgis’s division of two brigades was on its right, occupying the lower portion of the city. Next came Getty’s division of two brigades under cover of the bluffs at the mouth of Hazel Run. Burns’s division of three brigades on the left connected with Franklin at Deep Run, and was under his orders. During the day Burns went across Deep Run to Franklin’s support.

When French’s division was advanced, Sturgis was ordered to support it upon its left. He threw forward Dickenson’s battery and Ferrero’s brigade. The battery received a heavy fire from guns on and near Lee’s Hill, and was soon disabled and withdrawn, Dickenson being killed. Ferrero advanced from the lower part of the city to the left of the ground over which French and Hancock had fought. He did not have the canal to cross, as it terminated near the railroad. He met a severe fire, however, and finding depressions of ground in which his troops could get cover, his brigade occupied them for the rest of the day and fired from 60 to 200 rounds per man at the Confederate lines and batteries.

Sturgis’s second brigade, under Nagle, about an hour later, was ordered to support Sturgis’s on the left. After some delay in crossing ravines, this brigade also found cover somewhat to Ferrero’s rear, which it occupied and joined in the fire upon the Confederate lines until dark.

Ferrero’s casualties were 491 and Nagle’s 500. About 3 P.M., Ferrero having asked for reinforcements, and Griffin’s division having reported as support to the 9th corps, Barnes’s brigade, of that division, was sent in over the same ground that Ferrero had traversed. This brigade also made a gallant advance, but finally took cover with the loss of 500.

Meanwhile, Whipple’s division of the 3d corps, of two brigades, which had been placed at the upper end of the town to guard the right flank, having no enemy close in front, sent Carroll’s brigade to support Sturgis. Griffin placed Sweitzer’s brigade on the right of Carroll, and sent forward the two brigades supporting them with Stockton’s brigade, the last of his division.

This charge of Griffin’s was the eleventh separate effort made up to this time. But the infantry fire met was now being constantly increased, the Telegraph road affording the opportunity. Cobb had been killed and Cooke, soon after, severely wounded early in the affair. On the latter event, Kershaw with his brigade was ordered up, and about the same time, Ransom brought up the remaining three regiments of his brigade. Some of these troops doubled upon those already in the sunken road, until there were six ranks. These were effectively handled by Kershaw in person. Others took the best partial cover they could find about the top and slopes of the hill, whence their fire contributed to that from the sunken road. There the six ranks fired successive volleys from each rank, with only a few seconds’ intervals. A regiment from Jenkins’s brigade was also advanced down the right bank of Hazel Run, reinforcing a company of sharp-shooters which had been doing fine service all day upon the enemy’s flanks.

Under this increased fire Griffin’s charge differed but little in its results from those immediately preceding it. The men advanced as far as they could find some partial protection, and there they laid down. Carroll’s brigade here lost 118; Sweitzer’s 222; and Stockton’s 201. It was now nearly four o’clock and there came a comparative lull in the conflict. But Hooker was under orders to attack with his whole force, and he had yet intact Humphreys’s and Sykes’s divisions of the 5th corps. Even before Griffin’s charge, Hooker had looked at the field, and become so convinced that the Confederate line could not be carried, that he had sent an aid to Burnside to say that he advised against attack. The answer came that the attack must be made. Hooker, however, considered it a duty to his troops to make a fuller explanation, and endeavored to dissuade Burnside from what he was sure would be a hopeless effort. Burnside still insisted that the position must be carried before night.

Hooker, accordingly, returned and began to prepare for the attack by advancing as many batteries as could be located on the edge of the town, and even sending two, Hazard’s and Frank’s, across the canal, where they opened with a range of less than 300 yards.

While these preparations were going on, the troops holding the hollows and undulations in front, where they had found shelter when the charges had been repulsed, reported that the Confederates were withdrawing from their positions. This report was quickly spread and reached Couch, who said to Humphreys, “Hancock reports the enemy is falling back. Now is the time for you to go in.”1

Humphreys’s division was composed of two brigades, Allabach’s and Tyler’s, and it went into action 4500 strong. It was already under urgent orders to attack. Allabach’s brigade was in front, and Tyler’s in motion to get upon its right flank.

Now, without waiting for Tyler, Humphreys ordered Allabach to advance, and, throwing themselves in front, he and Allabach led the charge. In about 200 yards they reached the continuous line now formed of the fragments of the preceding charges, lying down where they could find cover. Here, in spite of all their efforts, Allabach’s troops also laid down and began to fire. Humphreys could now see the Confederate line, and appreciated that it was so covered that fire against it was of little effect. With some difficulty and delay he succeeded in checking the fire of his men, got them on their feet, and again started to advance. Up to this point his line had had partial cover, but now for 150 yards there was none. They advanced for 50 yards and then broke, a part stopping with the line of remnants, and the remainder were rallied near the canal.

Tyler’s brigade after a little delay was formed in a double line of battle on the left of Allabach’s position. It had first moved to the right, but there met enfilading fire of artillery, and it was withdrawn to the left. Humphreys joined it and ordered the charge to be made with the bayonet alone, and that the men should pass directly over the line of those lying down.

Meanwhile, as sundown approached, Burnside’s orders had grown urgent that the position should be carried before dark. Getty’s division of the 9th corps, two brigades, from the left on Hazel Run, was ordered to assault, but no steps were taken to have it simultaneous with that of Humphreys.

Had there been time, Humphreys, from his experience with Allabach, would have preferred to first clear his path of the line of men lying down, already spoken of. Not only were they physically much in the way, but even more were they a moral obstacle. A repulsed line, which is not ready to join in a fresh assault, does not at all like a new line to pass over it, for it seems a reflection upon their courage. They are apt to do all they can to discourage and obstruct the newcomers, and the latter cannot fail to appreciate that, an advance, leaving a large force behind, is very liable to receive fire from the rear, intended to go over their heads, but likely to land a good many bullets in their backs. And, even if this does not happen, a false alarm of “fire from the rear,” is almost sure to occur.

Under the conditions confronting him, Humphreys’s charge was utterly hopeless, and should never have been made. But it illustrated a high type of disciplined valor, and, but for the men lying down, might have crossed bayonets with the Confederates. The six ranks of seasoned veterans in the road, however, could scarcely have been overcome by those who would arrive.

With all its officers in front, led by Humphreys and Tyler, and with a loud hurrah, which was a signal to our guns on the hill to put in rapid work from full chests of canister, Tyler’s brigade now made a rapid advance under what, in his official report, Humphreys called “the heaviest fire yet opened, which poured upon it from the moment it first rose from the ravine.” They came in two lines, quite close together, and without firing a shot. A more beautiful charge is not recorded in the annals of the Army of the Potomac.

Its experiences, as told in the official reports both of Humphreys and Tyler, are instructive. Humphreys writes:—

“As the brigade reached the masses of men referred to, every effort was made by the latter to prevent our advance. They called to our men not to go forward, and some attempted to prevent by force their doing so. The effect upon my command was what I apprehended. . . . The line was somewhat disordered, and, in part, was forced to fall into a column, but still advanced rapidly. The fire of the enemy’s musketry and artillery, furious as it was before, now became still hotter. The stone wall was a sheet of flame that enveloped the head and flanks of the column. Officers and men were falling rapidly, and the head of the column was at length brought to a stand when close up to the wall. Up to this time not a shot had been fired by the column, but now some firing began. It lasted but a minute, when, in spite of all our efforts, the column turned and began to retire slowly. I attempted to rally the brigade behind the natural embankment, so often mentioned, but the united efforts of Gen. Tyler, myself, our staffs, and the other officers could not arrest the retiring mass. My efforts were the less effective, since I was again dismounted, my second horse having been killed under me. . . . Our loss in both brigades was heavy, exceeding 1000 in killed and wounded, including in the number officers of high rank. The greater part of the loss occurred during the brief time they were charging and retiring, which scarcely occupied more than 10 or 15 minutes for each brigade.”

Tyler’s report says:—

“The brigade moved forward, in as good order as the muddy condition of the ground on the left of my line would admit, until we came upon a body of officers and men lying flat upon the ground in front of the brick house, and along the slight elevation on its right and left. Upon our approach the officers commanded halt, flourishing their swords as they lay, while a number of their men tried to intimidate our troops by crying out that we would be slaughtered, etc. An effort was made to get them out of the way, but failed, and we marched over them. When we were within a very short distance of the enemy’s line, a fire was opened on our rear, wounding a few of my most valuable officers, and, I regret to say, killing some of our men. Instantaneously the cry ran along our lines that we were being fired into from the rear. The column halted, receiving at the same time a terrible fire from the enemy. Orders for the moment were forgotten, and a fire from our whole line was immediately returned. Another cry passed along the line, that we were being fired upon from the rear, when our brave men, after giving the enemy several volleys, fell back.”

Besides suffering from the infantry fire of their own men in the rear, the Federal column, or portions of it, also believed that the Federal artillery above Falmouth, which kept up a constant long-range fire with their heavy rifles upon the Confederate position, had mistaken localities and was landing its projectiles in the Federal ranks. Couch writes of this charge of Humphreys’s division, as follows, in the Century Magazine:—

“The musketry fire was very heavy and the artillery fire was simply terrible. I sent word several times to our artillery on the right of Falmouth that they were firing into us and were tearing our men to pieces. I thought they had made a mistake in the range, but I learned later that the fire came from the guns of the enemy on their extreme left.”

This fire came from Parker’s battery, of my battalion, located near the Stansbury house. The losses in Allabach’s brigade were officially reported as 562, and those in Tyler’s as 454.

The attacks by these brigades were the twelfth and thirteenth separate charges of the day, and there was still one to follow.

Getty’s division, comprising Hawkins’s and Harland’s brigades, received orders to attack about the same time that Humphreys was arranging his attack. Being near the mouth of Hazel Run, they had farther to advance before reaching the field, and only arrived upon it after Tyler was repulsed. They had not been engaged during the day, but had suffered some casualties from premature explosions of Federal shell fired from the hills across the river. Hawkins’s brigade led, advancing by right of companies as far as the railroad, where the brigade line was reformed and a fresh start taken, directed at the southern extremity of Marye’s Hill. Harland’s brigade was to follow in similar formation.

In view of the lateness of the hour, this charge was even more hopeless than any of the preceding. Hawkins had protested against it before starting, but the orders were explicit. By the time that the division crossed the railroad, it was so dark that distinct vision was limited to a few hundred feet. The first portion of the march was unobserved by the Confederates, and the line rapidly advanced until it came to marshy ground, through which ran a ditch to Hazel Run. Here they opened fire, and their position was defined to the Confederates by the flashes of their muskets, and infantry and artillery replied from Marye’s Hill, from across Hazel Run, and from guns upon Lee’s Hill. They crossed the ditch, however, and had advanced quite close to the sunken road, when suddenly the infantry in it opened fire, and, at the same time, fire was opened upon them from the right and rear by the line of Federals lying down, in front of whom their advance from the left had brought them. Hawkins thus describes the scene:—

“When the brigade arrived at this cut [ditch] it received an enfilading fire from the enemy’s artillery and infantry, but, notwithstanding, the plateau on the other side was gained, the left of the line advancing till within about 10 yards of a stone wall, behind which a heavy infantry force of the enemy was concealed, which opened an increased artillery and infantry fire, and, in addition to this, the brigade received the fire of the 83d Pa. Volunteers and of the 20th Me. Volunteers who were on the left of Gen. Couch’s line, which our right had overlapped. This firing from all quarters, and from all directions, I should think, lasted about seven minutes, when I succeeded in stopping it and then discovered that the greatest confusion existed. Everybody, from the smallest drummer boy up, seemed to be shouting to the full of his capacity. After considerable exertion, comparative quiet and order were restored, and the command re-formed along the canal cut [ditch]. I then reported to you for further orders, and you ordered the command withdrawn, and placed in its former position in the town.”

Getty not only showed good judgment in withdrawing Hawkins’s brigade on the first opportunity, but he had done even better with Harland’s brigade, for he halted it near the railroad, and did not permit it to participate in the charge. Sykes’s division was also held in reserve on the edge of the town, behind Humphreys, and at 11 P.M. was sent across the canal, where it relieved the remnants of all of the brigades which had made their advances from that quarter.

The Confederate fire soon ceased when the flashes of the enemy’s guns no longer gave targets. The losses in Hawkins’s brigade had been 255, in Harland’s they were 41.

Among the Confederates, no one conceived that the battle was over, for less than half our army had been engaged, only four out of nine divisions. It was not thought possible that Burnside would confess defeat by retreating.

Burnside himself, however, was far from having given up the battle, and, though many prominent officers advised against it, he determined to renew the attack at dawn. He proposed to form the whole 9th corps into a column of regiments and to lead it in person upon Marye’s Hill.

He came across the river after the fighting ceased, gave the necessary orders, and returned to the Phillips house about 1 A.M. He found there waiting for him Hawkins, who had made the last charge, and who had now come at the request of Willcox, Humphreys, Meade, Getty, and others to protest against the proposed attack, and to give information about the situation, which it was supposed that Burnside did not possess. A long conference ensued in the presence of Sumner, Hooker, and Franklin, the commanders of the three grand divisions. On their unanimous advice, verbal orders were sent countermanding the proposed assault. Before these could be delivered, many preparatory movements were under way. And while they were in progress, a courier bearing orders which disclosed Burnside’s plan, becoming lost in the darkness, wandered up to our picket-line. He was captured, and his orders were found and taken to Longstreet and Lee. Notice was at once sent along our lines, with instructions to extend and strengthen our intrenchments, and to make all necessary preparations of ammunition, water, and provisions, which was vigorously set about with no suspicion that Burnside would disappoint us.

So on the 14th, when, at dawn, the Confederates stood to arms, they looked and listened in vain for signs of the fresh assaults which the captured order had led them to expect. About 10 o’clock, the morning fog began to lighten, and a vicious sharpshooting sprang up. Sykes’s regulars were now in our front, and the guns from the Stafford hills kept up a slow target practice at our lines, to which we made no reply.

The day passed without serious hostilities. During the afternoon some of their shells prematurely exploding, caused orders to be issued not to fire any more at our position about Marye’s Hill.

During the night of the 14th, we received ammunition from Richmond, and Longstreet authorized a moderate fire on the 15th, to suppress the sharp-shooting. During the night, also, we had located two guns on our left where they could enfilade the sheltered position, in front of the canal, from which the Federal attacks had come.

So, on the 15th, our position was agreeably improved. A few shots, raking the depressions in which the enemy had so far found shelter, routed the picket reserves. A single shot into a loopholed brick tannery on the Plank road, silenced it, and for the rest of the day nothing annoyed us, and we worked openly at our defenses.

The night of the 15th was dark and rainy, with high wind from the south, preventing us from hearing noises from the enemy’s direction. During the night Burnside safely withdrew across the river. Commencing his movement at 7 P.M., his whole enormous force was across in 12 hours of a stormy night. It was a great feat, and its successful performance, unmolested, under our guns, reflects badly upon the vigilance of the Confederates. It should have been suspected, discovered by scouts, and vigorously attacked with artillery.

On the morning of the 15th, both Hooker on the right and Franklin on the left had applied to Burnside for permission to send a flag of truce and recover the wounded in their respective fronts. It seems that Hooker’s request was refused, for no flag was here shown. But on Franklin’s front an informal arrangement was made by which all picket firing ceased, and the Federal ambulances and burial parties were allowed to remove the dead and wounded in front of our pickets, and our own men brought forward and delivered those who had fallen within our lines. On the 16th, when the city was evacuated, very few of the wounded who had fallen on the 13th in front of the town were found alive.

The Federal guns were, generally, still in position on the hills on the north side, and a few spiteful shells were thrown by them in the early hours, but, before noon, the pickets of both sides were peacefully reestablished.

The whole action resolved itself into two separate offensive battles by the Federals, one on their right and one on their left, with some unimportant skirmishing in the centre. The forces present or near at hand on each field, and the losses, may be divided about as follows:—

Whatever may be said of Burnside’s strategy or tactics, he was not deficient in moral courage. Although well aware that most of his generals were in a despondent mood, he determined within a very few days to make a fresh effort. He had his cavalry reconnoitre the river below Fredericksburg, and then decided to cross in that direction.

On Dec. 26 he ordered three days’ cooked rations, and 10 days’ rations in the wagons, with beef cattle, forage, and ammunition, all to be prepared to move at 12 hours’ notice. His cavalry advance was already in motion for a raid within the Confederate lines, when he received a message from President Lincoln forbidding any movement without his being previously informed. This interference broke up his plan. Some of the generals had communicated it to the President with adverse criticisms.

Not discouraged, however, he soon devised another, and, doubtless, a better one. He proposed to cross the river at Banks Ford, only about four miles above Fredericksburg, making at the same time demonstrations at several points, both above and below. His losses at Fredericksburg had been more than repaired by the arrival within reach of the 11th and 12th army corps, some 30,000 strong, under Sigel. There had been good weather since the battle and the roads were in fair order. He had visited Washington and sought the approval of the President and War Department, but had found them reluctant to give it, being influenced by the general distrust of Burnside’s ability among the principal officers of his army.

To bring the matter to an issue, Burnside tendered his resignation, to be accepted “in case it was not deemed advisable for him to cross the river.” He then returned and hurried his preparation. On Jan. 20, he put his army in motion. Positions for 184 guns had been selected, covering the approaches to the points chosen for crossing, and roads had been found and opened as secretly as possible. But, nevertheless, the Federal activity had been noted, especially at Banks and United States fords, and, on the 19th, Lee sent a brigade to strengthen our pickets there. As the distances were not great from the Federal camps before Fredericksburg to the positions about Banks Ford, most of their guns were able to reach their positions by the night of the 20th. About dark on that day, a violent rainstorm set in, which continued all that night and the two following days. The pontoon trains in rear of the guns had farther to go, and were unwieldy to handle. Many troops and trains were still far from their destinations, and now every road became a deep quagmire, and even small streams were impassable torrents. Although desperate efforts were made all during the night to get the pontoons to the river, when morning dawned, not enough for a single bridge had arrived, and five bridges were required.

Swinton writes of the situation, as follows:—