BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA

Position of the Confederacy after Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Reinforcements of Bragg. The Armies before the Battle of Chickamauga. The Order of Battle. Engagement of the 19th. Battle of the 20th. Rosecrans’s Order to Wood. Longstreet’s Advance. The Casualties. Thomas at Chattanooga. The Battle of Wauhatchie. Bragg’s Positition. Battle of Chattanooga or Missionary Ridge. Positions of the Armies. The Attack on the Ridge. Bragg’s Retreat. The Knoxville Campaign. Longstreet;s Expedition. Fort Sanders and its Garrison. Storming the Fort. The Retreat. Casualties of the Campaign.

HAVING rested at Culpeper from July 24 to 31, and then crossed the Rapidan to Orange C. H., where we could receive supplies by rail, Lee’s army now recuperated rapidly from its exhaustion by the campaign of Gettysburg. There remained nearly five months of open weather before winter. The prospects of the Confederacy had been sadly altered by our failures at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Grant would now be able to bring against us in Ga. Rosecrans reinforced by the army which had taken Vicksburg. To remain idle was to give the enemy time to do this. Once more the necessity was upon us to devise some offensive which might bring on a battle with approximately equal chances. Lee, accordingly, urged forward the building up of his own army with the design of an early aggressive movement against Meade. It must be admitted that the opportunity for such was slight. The enemy’s fortified lines about Alexandria were too near; as was proven later, when in Nov. an advance was actually attempted.

But the Confederacy still held unimpaired the advantage of the “Interior Lines,” already spoken of as open to them in May, and then urged by Longstreet both upon Secretary Seddon and Lee. These still offered the sole opportunity ever presented the South for a great strategic victory. Already, however, movements of the enemy were on foot which, in a few weeks, would enable them to close the shorter route from Richmond to Chattanooga via Knoxville, and leave us only the much longer and less favorable line via Weldon, Wilmington, and Augusta. Unfortunately, no one but Longstreet seems to have appreciated this, and he was very slow in again taking up the matter and urging it.

It resulted that the movement, when attempted, was too late to utilize the short Knoxville line and that only five small brigades of infantry were transferred to the west in time to take any part in the hard-fought battle of Chickamauga. This was consequently but another bloody and fruitless victory to be followed by a terrible defeat in a few weeks when the enemy’s reinforcements had joined. It is first to tell of the dilatory consideration and slow acceptance of the proposed strategy, which should have been decided upon even before Lee’s army was again south of the Potomac, and every subsequent movement planned to facilitate it.

It was not until about Aug. 15, two weeks after the army was safe behind the Rapidan, that Longstreet again called the attention of Sec’y Seddon to the tremendous threatenings of the situation, and pointed out the one hope of escape which he could suggest. There seems to have been no reply. A few days later, in conversation with Lee, Longstreet again expressed his views. Lee was unwilling to consider going west in person, but approved the sending of Longstreet, and even spoke of his being given independent command there, if the War Department could be brought to approve.

About Aug. 23, Lee was called to Richmond, and was detained there by President Davis for nearly two weeks. During this time, consent was given that Longstreet should go to reinforce Bragg against Rosecrans, but with only Hood’s and McLaws’s divisions, nine brigades, and my battalion of 26 guns. It was proposed to send this force from Louisa C. H. by rail to Chattanooga, via Bristol and Knoxville, a distance of but 540 miles, and it was hoped that the movement could be made within four days.

There was too little appreciation of the importance of time in the enterprise proposed, and it was not until Sept. 9 that the first train came to Louisa C. H. to begin the transportation.

On that day 2000 Confederates under Gen. Frazier, who had been unwisely held at Cumberland Gap and allowed to be surrounded by a superior force, surrendered without a fight. Already Burnside had occupied Knoxville, leaving us only the long line via Petersburg, Wilmington, Augusta, and Atlanta, about 925 miles, with imperfect connections through some cities and some changes of gauge. The infantry was given precedence, and my battalion was marched to Petersburg, where it took trains about 4 P.M., Thursday, Sept. 17. At 2 A.M., Sunday, the 20th, we reached Wilmington, 225 miles in 58 hours. Here we changed cars and ferried the river, leaving at 2 P.M. The battle of Chickamauga was being fought upon the 19th and 20th, only five of our nine brigades having arrived in time to participate. We reached Kingsville, S.C., 192 miles in 28 hours, changed trains in six hours, and got to Augusta, 140 miles, at 2 P.M. on Tuesday, the 22d. Leaving Augusta at 7 P.M., we reached Atlanta, 171 miles, at 2 P.M., Wednesday. Leaving at 4 A.M., Thursday, we were carried 115 miles and landed at Ringgold Station, 12 miles from the battle-field, at 2 A.M. on Friday, Sept. 25. Our journey by rail had been 843 miles and had consumed seven days and 10 hours, or 178 hours. It could scarcely be considered rapid transit, yet under the circumstances it was really a very creditable feat for our railroad service under the attendant circumstances. We found ourselves restricted to the use of one long roundabout line of single-track road of light construction, much of it of the “stringer track” of those days, a 16-pound rail on stringers, with very moderate equipment and of different gauges, for the entire service at the time of a great battle of the principal armies of the Confederacy. The task would have taxed a double-tracked road with modern equipment.

Its efficient performance was simply impossible, and the incomplete success we were able to obtain by getting five brigades of Longstreet’s infantry upon the field, without any of his artillery, shows the soundness of our strategy, and is an earnest of what might have been accomplished, had a campaign upon our short interior lines been inaugurated in May, under Lee in person, instead of the unfortunate invasion of Pa. Indeed, it must be said of the battle itself, that the force upon the field was ample to have reaped the full fruits of victory, had its management been judicious. The story of the details, presently to be told, is but another story of excellent fighting made vain by inefficient handling of an army hastily brought together, poorly organized, and badly commanded.

It will be seen that the battle was opened by two divisions attacking the whole army of the enemy in a fortified position, the attack being made in a single line without supports at hand. They are defeated and put out of action for the day. Two more divisions try and fare little better. A fifth, in reserve, sends in one brigade without result; four are not engaged. The morning is gone and the battle of the Right Wing is over. That of the Left Wing has scarcely begun. It advances, finds by accident a gap in the enemy’s line, and drives off three divisions of the enemy. The left wing fights the rest of the enemy’s army (three-fourths of it) until near dark, when both wings unite and drive the enemy off the field; darkness covering his retreat. It is the old familiar story of piecemeal attacks.

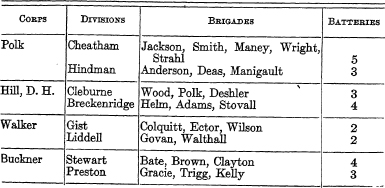

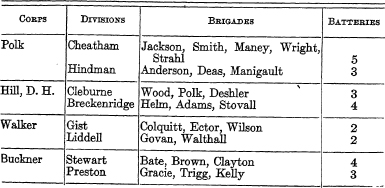

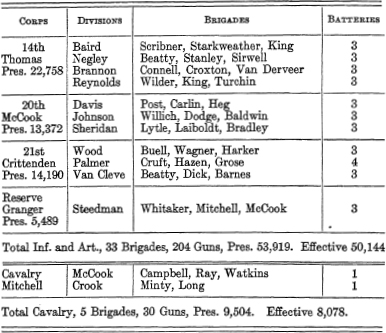

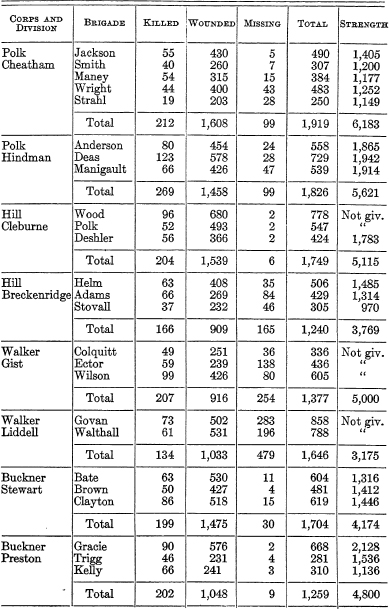

On the arrival of Longstreet, Bragg’s army would comprise five corps and a reserve division, organized as shown below. No exact returns of the total “present for duty” exist, but instead are given Livermore’s estimates of the “Effective Strength.”1

ARMY OF TENN., GEN. BRAGG. SEPT. 19-20, 1863

ARMY OF TENN., GEN. BRAGG, SEPT. 19-20, 1863

Unlike the armies in Va., which had never considered themselves defeated, our Western army had never gained a decided victory. Naturally, therefore, Lee enjoyed both the affection and confidence of his men, while there was an absence of much sentiment toward Bragg. It did not, however, at all affect the quality of the fighting, as shown by the casualties suffered at Chickamauga, which were 25 per cent by the Confederates in killed and wounded, exclusive of the missing.

Neither in armament, equipment, or organization was the Western army in even nearly as good shape as the Army of Northern Virginia. About one-third of the infantry was still armed only with the smooth-bore musket, calibre .69. Only a few batteries of the artillery were formed into battalions, and their ammunition was all of inferior quality.

Much has been said in the accounts of prior battles of the insufficient and unskilled staff service in the Army of Northern Virginia, even after many active campaigns. The Western armies generally had had far less opportunities to learn from experience, and fewer resigned ex-army officers from the old U. S. Army among them, to organize and train their raw material. Several of Bragg’s divisions had been recently brought together and were strangers to each other. Nearly all were unfamiliar with the country in which they found themselves, which was unusually wooded and hilly. Bragg, himself, was lacking in quick appreciation of features of topography.

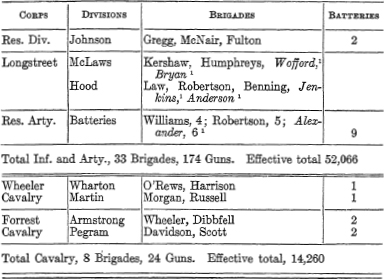

The organization of the Federal army, with its strength present for duty before the battle, is given below, and also Livermore’s estimate of the “Effective Strength.”

ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND, GEN. ROSECRANS, SEPT. 19-20, ‘63

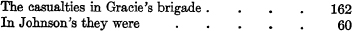

Comparing the two armies, we see that while Bragg’s “Effective total” (66,326) is largely greater than Rosecrans (58,222), it is due to Bragg’s excess in cavalry (6182), which arm had little opportunity in the battle upon either side. Of infantry and artillery, Rosecrans had an excess of 1853 men and 30 guns, besides the superiority of his small-arms and rifled artillery over the inferior equipment of the Confederates. It is well recognized that the defensive role is the least hazardous, and, on this campaign, Rosecrans, although on the strategic offensive, gladly seized the tactical defensive when Bragg incautiously gave him the privilege.

Bragg’s daily experience in the handling of his army should have warned him that it was not a military machine which could be relied upon to execute orders strictly, or to be alert to seize passing opportunities, and it is safe to say that its power for offense was scarcely 50 per cent of what the same force would have developed upon the defensive.

The position at Chattanooga held by Bragg at the beginning of the campaign was entirely untenable, as Rosecrans’s line of approach, along the Nashville and Chattanooga R.R., reaching the Tennessee River at Stevenson, threatened Bragg’s communications for 40 miles south, and he was forced to fall back without a battle and take position where he might guard his communications. He withdrew from Chattanooga on Sept. 8, and, moving south about 22 miles, disposed his forces in the vicinity of Lafayette and held the gaps in Pigeon Mountain, a spur of the great plateau of Lookout Mountain, running northeast, with McLemore’s Cove between the two. Rosecrans was misled by Bragg’s easy abandonment of Chattanooga into the belief that his retreat would be continued at least as far as Dalton, and perhaps to Rome. So, with little delay or caution, the Federal troops were pushed forward in rapid pursuit.

As the country was semi-mountainous, well wooded, and but sparsely settled, neither commander proved able to keep himself fully informed of his adversary’s movements. Each lost, therefore, possible opportunities of attacking isolated portions of his adversary with a superior force.

The most important of these was lost by Bragg, who, on Sept. 10 and 11, might have crushed, in McLemore’s Cove, parts of Thomas’s and McCook’s corps. Orders were issued for attacks, but there was no supervision of the necessary preparatory movements, and various obstacles intervened, until the enemy discovered his danger and made his escape. Bragg, in his official report, placed the principal blame for this failure upon Gen. Hindman, and preferred charges against him, which, upon further investigation, he subsequently withdrew. There can be no doubt that upon this occasion an opportunity was lost to the Confederates which might have won the campaign. But the loss was due entirely to the misfortune of inadequate organization, and lack of the trained staff, which alone can make an efficient army of any assemblage of troops. Of course, rumors of the sending of Longstreet with two divisions to reinforce Bragg, were sure ‘to, and did, reach the enemy by many channels and from many sources. Even from the lines along the Rapidan, there were deserters and negro servants who were well informed about all considerable movements. At Richmond and Petersburg, at Wilmington, Charleston, and Atlanta, the enemy, doubtless, maintained spies, and the coming of the reinforcements from Lee was no secret among Bragg’s brigades, even long before their arrival. One would suppose, too, that the wisdom of such strategy would be so apparent that it would be easily guessed, on hearing that any movement was on foot. It is, therefore, worthy of note that the Federal War Department, where reports and rumors from all sources were brought together and studied, even as late as Sept. 11, was inclined to believe that Bragg was reinforcing Lee. It was not convinced to the contrary until Sept. 15. Before that, Rosecrans had discovered the proximity of Bragg’s army and had hastened to concentrate his scattered divisions, some of which, mistaking the roads, made marches of 50 miles. The concentration took place in the valley of Chickamauga Creek, about 12 miles south of Chattanooga on the western slope of Missionary Ridge.

Bragg, meanwhile, realizing something of his opportunities, made more than one effort to strike in detail some of the nearest Federal divisions, but was unable to succeed. It was only on the night of the 17th that he finally issued an order for an advance in force upon the next day. Having waited so long, he had best have waited longer. Already he had given Rosecrans just the time needed to concentrate his entire army. Even a day sooner might have caught portions of it out of position and much exposed, but when the action opened on the 19th, not only was the whole Federal army in hand, but most of it had fairly well intrenched itself.

There was now no reason to hasten an attack, and there were two reasons for delay. First, by taking a threatening position, and using his superior force of cavalry upon Rosecrans’s rear, he might have forced the Federals to attack; and Bragg’s army, as has been said, was twice as powerful for defense as for offense. Second, he was now receiving reinforcements, averaging nearly a brigade a day. On the 19th, only Hood with three of Longstreet’s veteran brigades had reached the field. Longstreet, in person with two more, arrived in time to take part on the 20th. McLaws with four more brigades of infantry and 26 guns of the reserve artillery were close behind, and were enough to have turned the evenly balanced scale in the battle.

On Sept. 15, Rosecrans’s army was west of the Chickamauga, and had its right extended south beyond the left of Bragg’s army. Bragg’s right, at the same time, east of the Chickamauga extended north beyond Rosecrans’s left. Either army, changing front to its left, might thus have turned the other’s flank with great advantage, but neither was quite prepared to act promptly. Rosecrans, however, on the 17th, appreciated his own danger and began to extend his left and to draw down his right, practically moving his whole army to the left. This movement was continued during the night of the 18th and on the morning of the 19th. Before Bragg was prepared to open his attack, Rosecrans’s left had occupied the strong ground chosen for it to rest upon, on Kelley’s farm, about nine miles south of Chattanooga. From this point, the line extended to the Chickamauga at Lee and Gordon’s Mill, about four miles, with the divisions in the following order from left to right:—

Brannon, Baird, Reynolds, Palmer, Van Cleve, Wood, with Negley’s division in reserve, and the three divisions of McCook’s corps—Davis, Johnson, and Sheridan—massed near Crawfish Spring, near by on the right. At Rossville, six miles from Chattanooga and about three north of Kelley’s farm, was Granger’s reserve corps, of three brigades, holding the very important gap at that point in Missionary Ridge.

Bragg’s order of battle was of the progressive or echelon type, and prescribed that the attack should be begun by his right column under Hood, which should cross at Reed’s Bridge, and, turning to the left oblique, should sweep up the Chickamauga and be reinforced as it proceeded by Walker’s and Buckner’s corps, crossing by Alexander’s Bridge and Tedford’s Ford. Meanwhile Polk, at Lee and Gordon’s Mill, should press the enemy, bearing to the right where resistance was met, until a crossing was made at or between the mill and Dalton’s or Tedford’s Ford. Hill’s corps would watch the left flank and cross and attack the enemy’s right if he attempted to reinforce his centre. The cavalry would protect the flanks, Wheeler on the left and Forrest on the right. Cooking was ordered to be done at the trains, and cooked rations forwarded to the troops.

This order seems simple, well conceived, and apparently as well adapted to surrounding conditions as it could have been made, but its execution, as will be seen, departed widely from the course prescribed.

The right column under Hood, charged with the opening of the battle, was composed of three brigades of Hood’s and three of Bushrod Johnson’s. In reaching their assigned positions, there was much delay to all of the columns, due to the bad and narrow roads through the forest, and, in addition, Hood’s column was opposed by the enemy’s cavalry, and had a preliminary skirmish at Pea Vine Church. At Reed’s Bridge, and also at Alexander’s, it was necessary to force the crossing, and both bridges were so injured by the enemy that fords somewhere in the vicinity had to be used to cross the stream. These delays consumed the whole of the 18th, and, at nightfall, Hood’s six brigades and Walker’s five bivouacked on the west side of the Chickamauga about a mile and a half in front of the Rossville and Lafayette road, upon which Rosecrans began to arrive and take position before daylight on the 19th. Buckner’s corps, at Tedford’s Ford, having been directed to delay until Hood and Walker were across, had, after a slight skirmish, gotten possession of both banks of the river at Tedford’s, and also at Dalton’s, a half-mile to the left. Polk’s corps and Hill’s occupied the day in moving from the vicinity of Lafayette to their prescribed positions opposite the enemy’s right. At dawn on the 19th, the division of Buckner began crossing at Tedford’s and Dalton’s, but, before they were ready to attack, the initiative was seized by the Federals, under the impression that only a single Confederate brigade was in front of them. Croxton’s brigade, supported by the other two brigades of Brannan’s division, was ordered to advance. This brought on the battle, which was waged all day with severe losses on each side, but with material success on neither. The entire Federal army was engaged, except two brigades. Of the Confederates, the brigades of Anderson, Deas, Manigault, Helm, Adams, Stovall, Gracie, Trigg, Kelley, Kershaw, and Humphreys were not engaged. The fighting was desultory and without concert of action. From 7 A.M. until noon, there was a gap of about two miles between the 14th and 21st Federal corps, which, had the Confederates discovered it, might have given them the victory.

The fighting was kept up until dark. Longstreet arrived on the field at 11 P.M., having arrived at Catoosa Station about four, and ridden without a guide, narrowly missing riding into the enemy. The battle was ordered to be renewed at daylight, but under a different organization. The army was now divided into two wings, the right under Polk, and the left under Longstreet. To Polk’s wing was assigned Cheatham’s division of his corps, and the corps of Hill and Walker, with the cavalry under Forrest on the right. To Longstreet, Bragg gave the division of Hindman of Polk’s corps, Johnson’s division, Buckner’s corps, and the five brigades of Hood’s and McLaws’s divisions, with the cavalry under Wheeler on the left. This organization was adopted, because the troops were already approximately in the positions assigned, but it involved further subdivision of the command without any increase of staff, and led to an unfortunate delay of some hours in opening the battle.

This was to be begun by Hill’s corps at daylight. Sunrise was at 5.45. The orders were given by Bragg to Polk about midnight, but never reached Hill until 7.30 in the morning. The locations of the different commanders were not known to each other. When the orders to attack arrived, there were essential preparations still to be made, as the troops were not in position, and two hours were consumed in getting them even approximately so. These hours were very precious to the enemy. All during the night, the noise of his axes had been heard felling trees and building breastworks of logs, and this work was kept up until the Federal right, under Thomas, occupied a veritable citadel, from which assaults by infantry alone could scarcely dislodge him.

His divisions were in the following order from left to right: Baird of the 14th corps, Johnson of the 20th, Palmer of the 21st, Reynolds of the 14th. These divisions occupied the breastworks above described, which ran north and south and were terminated at each end by wings extending well to the rear. Next on the right was Brannan’s division of the 14th, and then Negley’s, of the same. Then came Sheridan and Davis of the 20th, and then Wood and Van Cleve of the 21st in reserve.

At 9.30 A.M., Breckenridge moved to the attack and was soon followed by Cleburne. These two divisions were unfortunately placed in a single line and without any supports in the rear. They advanced in the following order from right to left: Adams, Stovall, Helm, Polk, Wood, Deshler. The two right brigades of Adams and Stovall were found to entirely overlap the enemy’s line, and they pushed on slowly, and gradually swung to the left and came into collision with the retired portion of the enemy’s line. Meanwhile, the centre of Helm’s brigade had struck the enemy’s fortified line, and, after a severe fight in which Helm was killed, it was repulsed. The brigades of Adams and Stovall were now entirely isolated, but maintained their aggressive until Adams was himself wounded and captured, when they were withdrawn, and the three brigades cut no further figure in the battle until late in the afternoon. Had Cleburne’s division been behind this division in support, or even had their advance been simultaneous, there might have been a different story to tell.

Its three brigades—Polk, Wood, and Deshler—were also in single line and advanced a little after the repulse of Helm. Polk and the right flank of Wood’s met the same fire which had repulsed Helm. Wood and Deshler advanced farther before they received it, but they were all driven back with heavy losses, which included Deshler himself. The contest was kept up for a long time, and was reinforced by the five brigades of Walker’s division, who were brought up from the rear and put in at various points without making any serious impression. These brigades constituted the whole command of Polk in charge of the left wing, except the division of Cheatham which contained five brigades. Why neither Bragg or Polk put them in until after 6 P.M. is not explained. One would imagine that they would have been called upon before giving up the whole plan of the battle, which was now done. Originally, it had been designed to break the left flank of the enemy and then sweep him to the right. Now the effort will be to break the right flank and sweep to the left. And in this the right wing of the army will take no more part than the left wing has taken in the battle of the morning, and Cheatham’s division will practically take none at all.

About 11 A.M., Bragg, finding the attack on the enemy’s left making no progress, sent a staff-officer down the lines with orders to every division commander to move upon the enemy immediately. The order was first delivered to Stewart’s division of Buckner’s corps. This formed two lines deep and two brigades front, with the aid of Wood’s brigade of Cleburne’s division on its right. The four brigades, Brown and Wood followed by Clayton and Bate, advanced together. The enemy were driven by this charge some 200 yards and lost a battery of guns, but here the impulse was gone and the advance stopped. Meanwhile, Longstreet had appealed to Bragg for permission to attack with his entire wing, and, consent being given, had formed Johnson’s division with Fulton and McNair in front, with Gregg in the second line, and with Hood’s division in a third line. Hindman’s division formed on the left, and about 11.30 a general advance was essayed. Preston’s division was in reserve on the extreme left.

It is now time to look in the Federal ranks and see what was taking place there. Although the attack was only made at 9.30, and by only 12 brigades, and was resisted by Thomas with 12 brigades in fortified lines, yet, at 10.10 A.M., we find Garfield, Rosecrans’s adjutant, writing to McCook to be prepared to support the left flank, “at all hazards even if the right is drawn wholly to the present left.” At 10.30 he called for help, and Sheridan’s division was ordered to him. At 10.45, upon a further call, Van Cleve’s division was also ordered to support him “with all despatch.” Negley’s division had withdrawn from its position in line to support Baird, and had been replaced by Wood’s division, making the order of the divisions: Baird, Johnson, Palmer, Reynolds, Brannan, Wood, Davis, Sheridan. About this time another message from Thomas reached Rosecrans that he was heavily pressed, and the aide who brought it informed Rosecrans that “Brannan was out of line and Reynolds’s right was exposed.” On this Rosecrans dictated a message to Wood:—

“The general commanding directs that you close up on Reynolds as fast as possible and support him.”

This order changed the issue of the battle. Reynolds’s division was slightly echeloned with Brannan’s, but no one other than Reynolds considered it worthy of note. When Wood obeyed his order and reached the ground, Brannan was found to already occupy it, and Thomas sent Wood on to the support of Baird. Reynolds had blundered in his complaint, and Rosecrans had blundered in acting on it without reference to Thomas.

On receipt of the order, Wood, leaving his skirmishers in front, started his division at a double-quick to the left, passing in rear of Brannan’s division to reach the right of Reynolds. He had advanced but little more than a brigade length when Johnson’s Confederate division, supported by Hood and Hindman, burst through the forest in front and fell upon the movement. Had this movement of Wood’s division been foreseen by the Confederates and prepared for, it could not have happened more opportunely for them. Longstreet has been given great credit for it, which, however, he never claimed. It was entirely accidental and unforeseen, but in a very brief period it threw the entire left flank of the enemy in a panic.

Longstreet’s advance cut off the rear of Buell’s brigade of Wood’s division, and two brigades of Sheridan’s advancing to fill the gap being opened behind Wood. These brigades did not make enough resistance to check the Confederates, whose triple lines could be seen advancing and who now followed the fugitives. Hindman’s brigades, diverging to the left, routed the division of Davis and captured 27 guns and over 1000 prisoners. Rosecrans, McCook, and Crittenden were all caught and involved in the confusion of a retreat which soon became a panic. It was not, however, pursued and might have halted and been re-formed within a mile of the field without seeing the enemy. The retreat, however, was continued to Chattanooga. A severe check was sustained by Manigault, who attacked Wilder’s brigade. This brigade had two regiments armed with Spencer repeating rifles, and the 29th Ill. serving with it on this occasion, carried the same arm. They occupied a very favorable position on a steep ridge and their fire at close quarters was very severe and drove back the first advance. Then, finding themselves isolated, they presently withdrew from the field.

About this time, Longstreet was sent for by Bragg, who was some distance in rear of Longstreet’s present position. The change in the order of battle was explained to Bragg and the route of two divisions of the enemy, and he was requested to draw the forces from the right wing to unite with the left, and move behind Thomas, where a gap of great extent had been opened, and drive him out of his fortified position. Bragg, however, was discouraged, and said “there was no fight left in the right wing.” Cheatham’s division had not been engaged.

Longstreet’s account of the interview states:—

“He [Bragg] did not wait, nor did he express approval or disapproval of the operations of the left wing, but rode for his headquarters at Reed’s bridge. There was nothing for the left wing to do but to work along as best it could.”

A pause in the fighting now ensued, which the Federals employed in forming a new line for their centre and right with the troops remaining on the field,—Baird, Johnson, Palmer, and Reynolds,—whose positions had not been changed, and Brannan, with fragments of Wood, Negley, and Van Cleve. With these troops a short and very strong line was formed scarcely a mile in extent from right to left, and occupying favorable ground in the forest which gave it protection from artillery fire. In plan the right wing of this line covered two reentrant angles located on commanding ridges, from which they were able to deliver a plunging fire by volley, the ranks alternating with little exposure. During the afternoon they were reinforced by two brigades of Granger’s division coming up from Rossville. Practically about two-thirds of the army, say 30,000 men under Thomas, here held together in a strong position and stood practically back to back, while he repelled a series of desperate charges by the brigades of Anderson, Deas and Manigault, Gracie, Trigg and Kelley, Gregg, McNair and Fulton; and the five brigades of Longstreet, Kershaw, Humphreys, Law, Robertson and Benning, about 25,000. Not more than half of these brigades were engaged at any one time. The bayonet was sometimes used, and men were killed with clubbed muskets. This was kept up from 2 to 6 P.M., during which time the infantry fire was incessant and tremendous. About 5 P.M. Longstreet succeeded in getting 11 guns under Williams into position, whence their fire could take in flank and rear the positions of Thomas’s four left divisions; but the distance was about 900 yards, and the effect was not immediate.

About 6 P.M. the Confederates on the right flank, who had lain quiet since noon, recovering from their severe punishment in the morning, prepared to make a general advance. About the same time, Thomas had taken warning from the artillery fire now coming in on his flank and rear and made preparations to withdraw his command. He had also received orders from Rosecrans to withdraw to Rossville, but had delayed to execute them until the last moment. It had now come, and had he delayed longer his losses would have been great. As it was, they were comparatively light. At some points there were severe struggles and at others there was little resistance, but everywhere his lines were occupied and the triumphant Confederates celebrated their victory with such cheering as is said never to have been heard before.

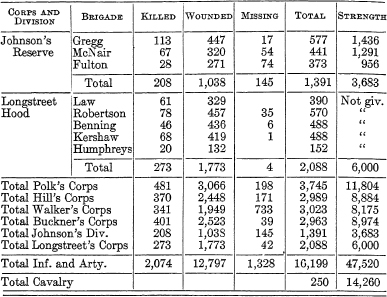

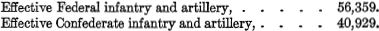

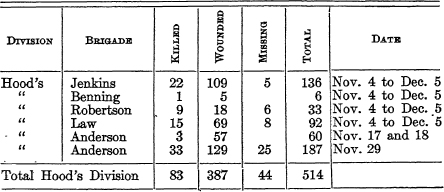

The table of casualties shows the heaviest percentages of the war. Deducting the missing, many of whom were prisoners, and also the losses of the cavalry, which were light, the killed and wounded among the infantry and artillery were 14,871 out of 47,520, or over 31 per cent among the Confederates.

CASUALTIES ARMY OF TENN., CHICKAMAUGA, SEPT. 19-20, 1863

CASUALTIES ARMY OF TENN., CHICKAMAUGA, SEPT. 19-20, 1863

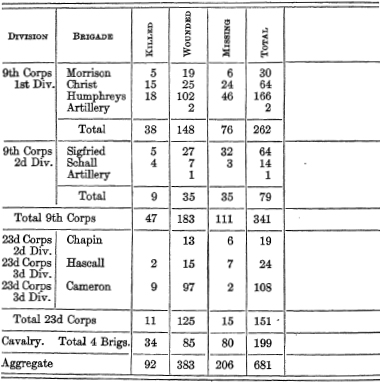

CASUALTIES ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND, CHICKAMAUGA, SEPT. 19-20, 1863

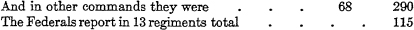

Among the Federal infantry and artillery the killed and wounded were 11,243 out of 55,799, or an average of about 21 per cent. No returns are given of the Confederate losses in the cavalry, but they were very light in the Federal cavalry, only 32 killed and 136 wounded, and there is no reason to suppose them any heavier among the Confederates. Apparently the forest paralyzed the cavalry of both armies.

Very many of the reports of the Confederate brigadiers state the number of men engaged, and these statements, excluding cooking details, ambulance men, and stragglers, are more exact than the official returns, and are used in estimating the percentages of killed and wounded. In Gist’s and Hood’s divisions only no figures are given, and here estimates have been made in round numbers.

There is much discrepancy in the reports of the two commanders as to the guns, small arms, and prisoners taken. Bragg reports 51 guns and 15,000 stand of small-arms. Rosecrans admits but 36 guns and 8450 small-arms, which is more probably correct. The Confederates were in the habit of exchanging their inferior guns and small-arms on the field for the better ones of the enemy, leaving the old in their places. Some of these found on the field were by mistake assumed to be captured. A list of the 51 reported captured is given in the reports with the manufacturers’ marks, and of these 15 appear as of Confederate make. Of prisoners, Bragg reports 8000, while Rosecrans admits but 4750. No accurate returns were made of the prisoners captured. The numbers were largely guesswork, the same prisoners being often claimed by more than one command. There is no reason to doubt the accuracy of Rosecrans’s report. It gives, also, some interesting statistics of the ammunition expended which was but 7325 rounds of artillery and 2,650,000 of infantry. The wooded character of the field is shown in the comparatively small amount of artillery ammunition which is said to have been “12,625 less than was expended at Stone River,” and is less than one-fourth of the Federal expenditure at Gettysburg.

On the morning of the 21st the army under Thomas was in position on Missionary Ridge, about Rossville, five miles in rear of the field of the day before. Here it took position and awaited attack all day, but none was made. Longstreet reports that he advised crossing the Tennessee River and moving upon Rosecrans’s communications, and that Bragg approved and ordered Polk’s wing to take the lead, while his wing cared for the wounded and policed the field. The army, however, was in such confusion and need of ammunition that it was dark before the rear of Polk’s corps was stretched out upon the road, and Longstreet’s march was postponed until the 22d. During the night Thomas withdrew into the city, which was already partially fortified, and was now easily made impregnable.

Bragg followed on the 22d and took position in front of him, Longstreet’s scheme of moving across the Tennessee River on Rosecrans’s communications he deemed impracticable and dropped it. The town was not invested closely, but position was taken on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, about three miles out, with the intention of compelling the evacuation of Chattanooga by cutting it off from its base of supplies at Stevenson, Ala.

The shortest and best road came via Jasper, crossed the river at Kelley’s Ferry, and, recrossing at Brown’s Ferry, found itself directly opposite Chattanooga on the north side of the river, about 40 miles from Stevenson. But this road could not be used. Below Kelley’s Ferry it skirted the river and was commanded by small-arms from the south side. This compelled the enemy to cross Walden’s Ridge to get by, adding many miles to their journey over exceedingly rough country.

The importance of holding strongly the country between the two ferries, Kelley’s and Browns’s, seems never to have been appreciated by either Bragg or Longstreet, who had charge of the left wing of the army. The duty was confided to a single small brigade, Law’s, of Hood’s division, which was sent around the toe of Lookout Mountain for the purpose. A full division at least should have guarded so important a point, and one so exposed.1

The opportunity to blockade the wagon traffic was not at once understood by the Confederates, and it was Oct. 11 before it was fully enforced. After that date wagons were often eight days in bringing a load from Stevenson, and reduced rations were issued to the Federals. Wheeler’s cavalry in a raid had destroyed most of the transportation of the 14th corps, but was itself nearly destroyed by the opportunity of plundering the wagons. Couriers reported that “from Bridgeport to the foot of the mountains the mud is up to the horses’ bellies.” On the 6th Rosecrans reported “the possession of the river is a sine qua non to the holding of Chattanooga.” Reconnoissances and preparations were made, and on the night of the 27th a flotilla of pontoons, carrying about 1500 men under Hazen, was floated down and landed at Brown’s Ferry. On the north side a force was marched by land to meet them, and a pontoon bridge was built. By morning a brigade with artillery was established and fortifying itself in a strong position on the southern bank. Before Bragg could concentrate enough to attack them, Hooker appeared, coming from Bridgeport, with the 11th and 12th corps of the Army of the Potomac. These had been hurried out to reinforce Rosecrans, when the Federals realized that Longstreet had reinforced Bragg.

This, of course, put an end to the contemplated attack, but, with very questionable judgment, Bragg ordered a night attack upon a portion of Geary’s division of the 12th corps (about 1500 strong with four guns), which had encamped at a point called Wauhatchie. This was about three miles from Brown’s Ferry, where Hooker, with the remainder of his force, had united with the force under Hazen.

THE BATTLE OF WAUHATCHIE

Night attacks are specially valuable against troops who have been defeated and are retreating. They are of little value under any other circumstances. The war, too, had now reached a stage where men had become impossible to replace in the Confederate ranks. Nothing could be more injudicious than to sacrifice them, even for a success, which would have no effect upon the campaign.

That was the case in this instance. Near at hand, the Federals had double or treble the force of the Confederates, and the camp to be attacked was two miles within the Federal lines. The attack must be made, the fruit of it be gathered, and withdrawal accomplished before the light of dawn; for with the dawn, or even before it, an overwhelming force of the enemy would cut off the withdrawal.

The only troops available for the attack were four brigades of Hood’s division, under Jenkins, which had been brought around the high toe of Lookout Mountain. This road was exposed to batteries on the north side of the river and could only be used at night. Three of the brigades, Law, Benning, and Robertson, had suffered severely, both at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and scarcely averaged 700 men each. These brigades were ordered to cross Lookout Creek, and seize the road between Hooker’s camp near Brown’s Ferry and the camp of Geary to be attacked. The remaining brigade was Jenkins’s own, now under Bratton, and was about 1800 strong.

Law, with two regiments, had opposed Hazen’s landing on the 27th, and skirmished on the 28th with the advance of the 11th and 12th corps under Hooker, but had now withdrawn across Lookout Creek. From the mountains above, a fine view was afforded of the valley with Hooker’s camp at the north end, and Geary’s three miles behind it. Jenkins had been summoned before sundown to view it and get some idea of the topography. He returned after dark and joining Law discussed the enterprise, which Law strongly advised against. The orders, however, were peremptory and there was no superior at hand to appeal to. The moon was about full, and soon after dark Law moved with his brigade across the bridge and, after some time spent in exploration, took position on a ridge nearly parallel to the road between Brown’s Ferry and Wauhatchie, and some 50 to 150 yards distant. It was about two miles below the camp of Geary’s division, and less than a mile above the encampments of the 11th and 12th corps. The Texas brigade reporting to Law, he placed two of its regiments on his left and one on his right, and sent the 4th regiment to hold the bridge in his rear. Benning’s brigade was sent to ambush the road farther ahead.

This effort to hold the road against efforts to reinforce Geary might have been much more effective had Law thrown his brigades boldly across the road, with perhaps two brigades in his front line supported by the third in a second line. He probably failed to adopt this policy only because he was too conscious of his weakness. His retreat was more assured and easier from the position which he took. And, in view of the risks attendant on the venture, and the small chances of success, it may have been the more prudent course.

In the placing of Law’s command there had been a few picket shots about 10 o’clock, which had caused Geary’s command to be put under arms and to be unusually alert. Soon after midnight their own picket challenged and was shot down, upon which the camp was alarmed, all lights extinguished, and the troops formed in line. The weather was somewhat cloudy, making the moonlight fitful. Jenkins endeavored to restrain his men from firing as they deployed before the camp, but it was in vain, and gradually the regiments extending on each side overlapped the Federal line and awaited an attack on the Federal rear by Lt.-Col. T. M. Logan, with a force of sharp-shooters, who had passed around to the rear. Their attack was to be a signal for a general charge. About an hour had now elapsed.

It was just at this juncture that Jenkins gave orders to withdraw. Law had notified him that the enemy had passed his position, which was a mistake. The road had been open all the while, but no troops had passed. On the opening of the attack upon Geary there had been a general alarm in all the camps below, and several brigades had been ordered to go to his relief. The first brigade passing Law’s ambush received volleys which, in the darkness, did little harm but threw their lines into confusion. Forming then parallel to the road, the Federals charged Law’s position, but were at first repulsed. Re-forming, and extending their lines, Steinwehr’s division made a second attempt, but Smith’s brigade, which struck Law’s front, was again repulsed with heavy loss. The men, however, did not on this occasion fall back to the foot of the hill, but rallied in the darkness of the woods, near at hand, until a part of the 136th N.Y., which had overlapped Law’s front, had appeared in his rear. The attack being then renewed was successful all along the line, and Law fell back toward the bridge, not being pursued. Robertson, who had had eight casualties, and Benning, who had had none, also withdrew, as the retreat of Law compelled.

Meantime, in the confusion of the night a column of two Federal brigades, ordered to go direct to Geary’s help, had halted without orders, and was overlooked for nearly two hours. Owing to this oversight, and the non-pursuit of Law, both he and Jenkins were able to cross the bridge before daylight.

No artillery was used by the Confederates, but Knaps’s battery of four guns, with Geary, was severely engaged at close quarters, expending 224 rounds and losing 3 killed and 19 wounded.

Geary’s total casualties were:—

34 killed, 174 wounded, 8 missing: total 216.

These all occurred in Greene’s and Cobham’s brigades about 1600 strong. The Federal casualties in the brigades opposing Law were:—

45 killed, 150 wounded, 7 missing: total 204.

These occurred principally in Tyndale’s and Orland Smith’s brigades. The aggregate was 420. The Confederate casualties reported are as follows:—

Law: 3 killed, 19 wounded, 30 missing: total 52.

Jenkins: 31 killed, 286 wounded, 39 missing: total 356. Aggregate 408.

The character of the attack by Jenkins’s brigade, and of the defense by Greene’s and Cobham’s, aided by the battery, had been excellent. The casualties were heavy, and included many officers distinguished among their comrades for conduct. Nothing less could have been expected, and nothing materially more could be hoped for, and such considerations should have forbidden this adventure. The guarding of the rear by Law proved a success, though due to a Federal mistake, not to his disposition. Only about half his force was engaged. It repulsed two attacks, but was swept away by the third. The enemy, however, made no advance and a free road, left open until after daylight, provided an escape for all four brigades from one of the most foolhardy adventures of the war. A Court of Inquiry in the 11th corps was held, which found that Krzyzanowski’s brigade had halted without authority and against the orders of the division commander, when under orders to go to Geary’s assistance.

These operations left Rosecrans with free communications by the shortest and best roads, and at liberty to receive all the reinforcements coming to him. Besides the 11th and 12th corps, under Hooker, already near at hand, it was known that Grant was bringing up a large force under Sherman from Memphis, and it was clear that within 30 days a force would be concentrated against us sufficient to overwhelm us. Rosecrans had now converted Chattanooga into a citadel, impregnable to assault by storm, within which he could confidently await the accumulation of whatever force was needed.

The burden of the attack was upon us. We must promptly take the aggressive, and meet and defeat, either Grant and Sherman approaching from the west, or Burnside, near at hand and threatening on the east, and be able then to reconcentrate our army against the other adversaries. President Davis had recently paid a visit to the army, which, it was known, was dissatisfied with Bragg as a commander, but after some investigation had decided to sustain him. Bragg, accordingly, had the decision of the question what should be done.

On Nov. 3 he issued orders for Longstreet’s corps, with Wheeler’s cavalry, to attack Burnside’s corps at Knoxville, which was to be assailed at the same time by a force of perhaps 4000 men under Ransom, coming from southwest Virginia. With the remainder of his army, Bragg proposed to hold his present lines, in front of Chattanooga, during the absence of Longstreet’s division. As these lines occupied a concave front of fully eight miles against an enemy concentrated within four, they were necessarily weak and unable to quickly reinforce threatened points. Longstreet pointed out their disadvantages and urged a withdrawal of the remainder of the army to a strong defensive position behind the Chickamauga River, and that his own force for the attack of Burnside at Knoxville should be increased to 20,000 men, to insure quick and easy work, and save any dependence upon the hypothetical force from southwest Virginia. Bragg, however, overruled all suggestions, and Longstreet was put in motion on Nov. 4 for Knoxville, with Wheeler’s two divisions (four brigades) of cavalry.

The result was what might have been expected, and we may anticipate and record it, briefly, before following Longstreet in his adventure against Knoxville.

THE BATTLE OF CHATTANOOGA OR MISSIONAEY RIDGE

On Oct. 22 Grant had reached Chattanooga and superseded Rosecrans. By Nov. 20 he had concentrated at Chattanooga about 65,000 infantry and artillery present for duty, and provided siege artillery for the forts about Chattanooga. Bragg, meanwhile, had further reduced his force by sending Bushrod Johnson with two brigades, 2500 men, to Knoxville, who joined Longstreet just too late to be of any service. This had reduced his force to about 40,000 infantry present for duty, greatly handicapped by their position in the long concave exterior line. On Nov. 22 Grant took the aggressive and set on foot attacks upon Bragg’s extreme right and left flanks. On the morning of the 24th Hooker turned the extreme left flank at Wauhatchie, in the valley of Lookout Creek, by climbing the slope of Lookout Mountain to the foot of the palisade. This palisade is a precipice dividing the top of the mountain from the slopes forming its toe. These were held by one brigade of Bragg’s infantry who were advanced some distance down the slope. Advancing along the foot of the precipice he took the Confederate positions on the toe of the mountain in reverse. They were also exposed to artillery fire from the front across the river and were thus surely driven out, about as fast as Hooker’s men could pick their way along the steep slopes at the foot of the precipice, which bounded the mountain on the west.

Ten miles away on the right flank, Chickamauga Creek emptied into the Tennessee by two mouths, and, in the eastern mouth of the creek, Grant had concealed a number of pontoons, and behind the hills north of the river was Sherman with over three divisions. On the morning of Nov. 24 a bridge was built across the Tennessee and 12,000 men were brought across and made a lodgment on the east end of Missionary Ridge, before Bragg was aware of it.

At sunrise, on the 25th, both Hooker and Sherman were ordered to attack. When Hooker advanced it was discovered that during the night of the 24th, the Confederate forces had abandoned Lookout Mountain and withdrawn all of their men across Chattanooga Creek, burning the bridge. Hooker followed in pursuit with three divisions, Osterhaus’s, Cruft’s, and Geary’s, about 10,000 men. About four hours were lost in rebuilding the bridge. Beyond it, only a feeble resistance was developed near Rossville on the western extremity of Missionary Ridge by two regiments of Stewart’s division. Stevenson’s division, which had held Lookout Mountain, had been transferred during the night to the extreme right to oppose Sherman. Hooker placed Osterhaus on the right of the ridge, Cruft on the ridge (which being narrow he occupied with three lines), and Geary on the left or front of the ridge. In this formation he advanced almost unopposed and with slight loss until he connected about sundown with Johnson’s division of the 14th corps, which had formed a part of Thomas’s attack upon the centre in the afternoon, as will presently be described.

Sherman had had the entire day of the 24th practically unmolested to establish himself on the northern extremity of Missionary Ridge, and reinforcements from Chattanooga had reached him in the afternoon. Soon after sunrise on the 25th he moved to the attack. A wide depression in the ridge separated the portion of it which he occupied from that held by Bragg. Here, during the afternoon and night, Hardee had intrenched Cleburne’s division and prepared to make a desperate stand. Sherman’s men, fresh from Vicksburg, attacked with great vigor, and being repulsed, renewed the attack several times with no better success. Sherman, in his report, denies that they were repulsed, but says:—

“Not so. The real attacking columns of Gen. Corse, Col. Loomis, and Gen. Smith were not repulsed. They engaged in a close struggle all day, persistently, stubbornly, and well.”

This is one way of stating it. Their charges were all driven back, with losses more or less severe, to the nearest places affording cover. From these they kept up musketry fire, with little loss or execution, all the rest of the day. Some reinforcements sent on the flanks did similarly, and before three o’clock in the afternoon Sherman’s whole force had been fought to a standstill, and Cleburne held his position intact and with very little fighting the rest of the day.

But Grant’s third attack, the one upon the centre, was yet to be made. It was to be upon Missionary Ridge and the topography requires some description. The ridge is here an average of some 200 feet high, with steep slopes, averaging on each side fully 500 yards wide. Many ravines and swales intersect the surface, which had been wooded but was now recently cleared, leaving many stumps. When the position was first occupied, a line of breastworks had been built at the foot of the slopes, between one and a half and two miles from the Federal lines. Later some unfinished breastworks were erected halfway up the hill.

The Confederate engineers now seemed at a loss to decide exactly where to make their final stand, and only at the last did they decide to make it at the proper place, at the top of the hill. But with it they made the fatal mistake of dividing their forces, already too small, and putting one-half in their skirmish line, at the bottom of the hill, and the other half at the top. Very few of the Confederate reports of this battle have been preserved, but many interesting details are given in papers, left by Gen. Manigault of S.C., who commanded a brigade in Hindman’s division. The construction of the works was only begun on the 23d, with a very insufficient supply of tools. The ground was hard and rocky, and when the assault was made on the 25th, the trenches were but half completed, and only afforded protection to the lower part of the body. The Confederate engineer who laid it out had orders to locate the line upon the highest ground, and blindly obeyed. At many places this left numerous approaches, up ravines and swales, entirely covered from the fire of the breastworks. Manigault persuaded the engineer, who complained of having too much to do, to allow him to lay out his own line, and at such places he located the line below the crest so as to sweep the whole approach. Brigades to the right and left did not do this, and there were many places where an assaulting column could approach within a short distance without receiving any fire.

The fatal mistake of dividing the force seems to have been decided on during the night of the 24th, for it was not done until the morning of the 25th. One-half of each brigade was then sent to the line at the foot of the hill, and the remainder to the line at the top. This disposition of forces was made in all the troops on the ridge, and the number available gave, in each position, only a single rank, with the men about one pace apart. Private instructions were given the superior officers, if attacked by more than a single line of battle, to await the enemy’s approach within 200 yards, then to deliver their fire, and retire to the works above. This was an injudicious order, as will be seen—impracticable of successful execution after the enemy had gotten that near in such large force.

About noon the enemy began to form in masses in front of our centre, about two miles away. About two o’clock these masses deployed and formed two lines of battle, with a front of at least two and a half miles. After completing their arrangements these moved within a mile of our lower works and halted. Behind these two lines a reserve force, apparently equal in number to one of them, was disposed at intervals in close columns of regiments, and followed them some 300 yards in rear. The whole array was preceded by a powerful line of skirmishers deployed at half distances. One could not but be struck with the order and regularity of the movements and the ease with which the Federals preserved their lines. The sight was a grand and impressive one, the like of which had never been seen before by any one who witnessed it.

Manigault writes:—

“I felt no fear for the result, even though the arrangements to repel the attack were not such as I liked, neither did I know at the time that a column of the enemy was at that moment on our left flank and rear, or that our army numbered so few men. I think, however, that I noticed some nervousness among my men as they beheld this grand military spectacle, and I heard remarks which showed that some uneasiness existed, and that they magnified the host in their view to at least double their number.”

The reference made to the “column of the enemy at that moment on our left flank and rear” is to the three divisions under Hooker, advancing from Rossville on both sides of Missionary Ridge. They were due to reach the field about sundown.

For some time after the last halt of the enemy there was an ominous silence over the whole field, except for an occasional distant cannon-shot. Sherman’s battle, from one to two miles to the right, had been fought out. Hooker was marching cautiously unopposed, and, by a sort of tacit understanding, even the skirmishers in front paused in contemplation of the coming storm.

The attack on the Confederate centre was assigned to Thomas, who had been in readiness all the morning, but was still delayed by Grant, who hesitated to order it until either Sherman had turned our right flank or Hooker had turned our left. Hooker was delayed and does not seem to have been heard from. Sherman had been fought to a standstill; but thinking that he saw reinforcements moving from the Confederate centre against Sherman, Grant directed Thomas to give the signal. It was a dozen guns, fired by the enemy, and was followed by the opening of their whole line, and soon after by our own guns from Missionary Ridge directed at the dark masses of their troops. The effect of a plunging fire, however, from our high elevation, was distinctly less than it would have been upon a plain, and when the enemy’s lines were set in motion, which soon followed, it was apparent, at a glance, that our artillery was utterly inadequate to the task of stopping the great force before us.

Meanwhile one-half of the whole Confederate force was under secret orders to retreat when the enemy arrived within 200 yards, and the enemy’s generals were themselves under orders from Grant not to advance beyond our skirmish line. Manigault thus describes what took place:—

“When the enemy had arrived within about 200 yards our men gave their volley, and a well-directed and fatal one it proved, but then followed a scene of confusion rarely witnessed, and only equalled at a later hour on that day. The order had been issued to retire, but many did not hear it, owing to the reports of their own pieces and the deafening roar of artillery. Others supposed their comrades flying and refused to do likewise. Some feared to retire up the hill, exposed to a heavy fire in their rear, feeling certain, as their movements must be slow, that they would be killed or wounded before reaching their friends above. All order was lost, and each striving to save himself took the shortest direction for the summit. The enemy seeing the confusion and retreat moved up their first line at a double quick and came over the breastworks, but I could see some of our brave fellows firing into the enemy’s faces and at last falling overpowered. . . .

“The troops from below at last reached the works exhausted and breathless, the greater portion so demoralized that they rushed to the rear to place the ridge itself between them and the enemy. It required the utmost efforts of myself and other officers to prevent this, which we finally succeeded in doing. Many fell, broken down from over-exertion, and became deathly sick or fainted. I noticed some instances of slight hemorrhage, and it was fifteen minutes before the nervous systems of those men were so restored as to be able to draw a trigger with steadiness.”

In the meantime, Grant had observed the battle from his commanding position in the rear. As above said, he thought he had seen Bragg detaching troops from his centre, opposite Thomas, and sending them to reinforce the right opposite Sherman, and many Federal reports, ever since, have fallen into the same error. But all are wrong. Sherman had been fought to a standstill, and Cleburne had no need for reinforcements. Also, Thomas’s preparations could be seen too plainly. So the elaborate strategy, which had sent Sherman to turn Bragg’s right, came to naught at the fighting point. Grant had seen, with much satisfaction, the Confederate lower line of intrenchments in the possession of his forces. But, as he looked, he was surprised to see, at a number of points, that his men had not halted as he had ordered, but were beginning to climb the slope and advance against the fortified line at the crest. He asked angrily: “Who ordered those men up the hill?” and, when all present disclaimed it, said: “Some one will suffer for it, if it turns out badly.” But the men themselves, having reached the designated position, were able to take a more practical view of it than the general himself at a distance.

It would be impossible for the troops to remain in the new position under the fire of the Confederate line at the top of the hill. There was nothing to do but to follow the fugitives and endeavor to mingle with them. As the pursuers advanced, they soon appreciated the fact that the ravines and swales afforded more or less protection from fire, and the whole line soon divided and concentrated itself on about six separate lines of advance. Not one of these was on the front held by Manigault’s brigade. Every attempted advance here had been met with fire, before which it either fell back to cover, or disappeared to the right or left. Next on the left was Patton Anderson’s brigade of Missis-sippians, and next on the right was Deas’s brigade of Alabamians. A large number of Federals soon found shelter behind some overhanging rocks in Deas’s front within 20 yards of his line of battle. Manigault turned a gun upon them and they were driven from view, but beyond a turn of the rock, they got a lodgment in large numbers, so that the division commander called for and took Manigault’s largest regiment to reinforce Deas.

Meanwhile an officer from the left reported that the enemy had broken the Miss. brigade, and, going to the left to get a view, Manigault saw the Federals in possession of the Miss, battery and the brigade retreating in disorder. The Federals soon turned the captured guns upon his line, enfilading a portion of it, and about the same time the Alabamians on the right also gave way. His own men on the flanks were still fighting well, but the centre, the part being enfiladed, even now wavering, would soon melt away.

A ridge some 500 yards to the rear offered favorable ground for a rally, and, seeing that all was lost and to check the fugitives impossible, he commanded a retreat, directing the officers to rally the men upon that ridge. A rapid run-for-it was successfully made, with some loss under a heavy fire, but about two-thirds of what was left of the brigade were rallied on the ridge, and were soon joined by the remnants of the Ala. and Miss. brigades. Manigault saved two of his guns, but two were captured. The enemy seemed contented with his success and did not pursue, and the firing ceased all along the line except at the extreme right, where Cleburne and the troops opposing Sherman still held their ground until withdrawn after dark.

Considering how utterly the centre of his line was routed, Bragg made a surprisingly good retreat, the enemy not pursuing vigorously. Bragg crossed the Chickamauga that night, destroying the bridges behind him. On the 26th, he retreated to Ringgold, where on the 27th he repulsed a pursuing force which then retired. The army then withdrew to Dalton, where, five days later, Bragg, at his own request, was relieved of the command. He lost his campaign primarily when he allowed Rosecrans to reopen the short line of his communications. Sending Longstreet to Knoxville while holding such advanced lines cannot be excused or palliated. It was a monumental failure to appreciate the glaring weakness of his position. His men never really fought except against Sherman on his extreme right, and there they were victorious and retreated unmolested after night. He was simply marched out from his position on Lookout, and he would have been also marched off of Missionary Ridge by Hooker, had not Grant grown impatient. The unwise division of his forces had put it in Grant’s power to defeat him by marching with at least 50 per cent less than the usual fighting.

Bragg’s casualties were but 361 killed and 2160 wounded, about the average of a single corps or one-sixth of those at Chickamauga. But he lost 40 guns. Grant’s losses were also but small, on Lookout Mountain and on Missionary Ridge. They were heaviest where Sherman attacked Cleburne’s and Breckenridge’s divisions, but even there where the fighting was prolonged most of the day, there were no such casualties as there had been at Chickamauga.

Grant’s total was 753 killed, 4722 wounded, 349 missing. Total 5824.

Livermore estimates the forces engaged on each side as follows:—

THE KNOXVILLE CAMPAIGN

On Nov. 3, as has been told, Longstreet was ordered to march against Burnside in E. Tenn., with McLaws’s and Hood’s divisions of infantry, Alexander’s and Leyden’s battalions of artillery (of 23 and 12 guns) and five brigades of cavalry under Wheeler with 12 guns. This force numbered about 15,000, of which about 5000 were cavalry and 10,000 infantry and artillery. Cooperation was promised from southwest Va. by a force of about 4000 under Ransom, but it was too late in starting, and its infantry and artillery only reached Longstreet on his retreat northward after the siege of Knoxville.

It was designed to move Longstreet by rail from Chattanooga to Sweetwater, Tenn., within 40 miles of Knoxville. This, it was hoped, could be easily done by the 7th or 8th. The artillery and McLaws’s division were marched to Tyner’s Station on Nov. 4, and Hood’s division to the tunnel through Missionary Ridge on the night of the 5th. Trains, however, could only be furnished to carry them to Sweetwater by the 12th, and it was the night of the 14th before a pontoon bridge could be thrown across the river at Huff’s Ferry near London, and the advance upon Knoxville, 29 miles off, actively undertaken. The men and guns of my own battalion were carried on a train of flat cars on the 10th, the train taking over 12 hours to make the 60 miles. The cannoneers were required to pump water for the engine and to cut up fence rails for fuel along the route, and the horses were driven by the roads.

The forces of Burnside at Knoxville consisted of four small divisions, two of the 9th corps, and two of the 23d, about 12,000 infantry and artillery and 8500 cavalry. The cavalry, during the coming siege, for the most part held the south side of the river, where they erected strong works on the commanding hills and were little molested, as our own cavalry was generally kept on the north bank on our left flank. Burnside was ordered not to oppose Longstreet’s advance, but to retreat before him and draw him on, as far as possible from Chattanooga. On Sunday, Nov. 15, Longstreet crossed and advanced as far as Lenoirs; Burnside falling back, skirmishing. On the 16th, an effort was made to bring him to battle at Campbell’s Station, but only a skirmish resulted, in which the Federal loss was 31 killed, 211 wounded, and 76 missing, and the Confederates 22 killed, 152 wounded. Burnside withdrew into Knoxville that night and Longstreet followed and drew up before it on Nov. 17. On the 18th, the outposts were driven in and close reconnoissances made, in which the Federal Gen. Sanders was killed. He had been recently promoted, was an officer of much promise, and a relative of President Davis. The reconnoissances developed the enemy holding a very strong defensive line with but a single weak point. This was the northwest salient angle where their north and south line, running perpendicular to the river below the town, made a right angle and turning to the east ran parallel with the river to the northeast of the town. There it rested, behind an extensive inundation of First Creek, upon a strong enclosed work on Temperance Hill, mounting 12 guns, with outlying works upon Mabry’s and Flint Hills.

These had been built, with several other works, during the prior Confederate occupation, and one, enclosing three sides of a rectangle about 125 by 95 feet with bastion fronts, the rear being open, had been nearly completed at the northwest salient angle above referred to. This was now called Fort Sanders, after the general killed on the 18th, and every exertion was used to complete and strengthen it, all able-bodied inhabitants of the town being impressed, both white and black, to aid in labor upon the fortifications. The Confederate engineer who laid out this work had injudiciously turned the salient angle of its northwest bastion directly toward the valley of Third Creek, just at the point where this valley allowed an approach, within 120 yards, completely covered from the fire of the fort. A convex crest of the valley curved from this point to the east and south, and sheltered a large territory, affording space for many brigades to be held completely under cover, within distances of from 150 to 400 yards of the enemy’s intrenchments. These conditions made it the most favorable point for attack, and, indeed, the only one at all favorable north of the river.

A third of the enemy’s northern front was protected by inundations of First and Second creeks, across which his guns had open sweep for a mile. To make a large circuit, and turn it, would be to abandon our communications with our base of supplies. An attack upon either of his short flanks running back to the river would be enfiladed from the south bank. Two strong enclosed works, Fort Comstock and Battery Wiltsie, covered the only approach between the inundations.

The theory of Longstreet’s expedition was that he should take a much superior force and make short work of it. In fact, we had an inferior force of infantry and artillery, until after the arrival of Johnson’s and Grade’s brigades, which will be referred to presently. The cavalry on neither side took any part in the siege operations. We had now to take the offensive which made the task harder, but yet we seem to have stood a fair chance to carry Fort Sanders had we made an attack with all our force soon after our arrival. But every day of delay added to the strength of the enemy’s breastworks, and in a very few days he had an interior line which might have successfully resisted, even had Fort Sanders been captured. It is now to tell how the 10 days were consumed which were allowed to intervene before the attack. By that time a second line had been constructed which might or might not have survived the loss of the first.

The 20th saw our own line finished with batteries erected to repel any offensive movements of the enemy, and, incidentally, enfilade some of the lines of Fort Sanders, which was already recognized as the most feasible point of attack. Had the advantage of an early attack been fully realized, it might have been organized and delivered on the 21st, or at latest by the 22d. But on that day one of our staff-officers, who had crossed the Holston River on our right flank and reconnoitred the country, had found it possible to locate a battery upon a high hill close to the river, giving an advantageous line of fire upon Fort Sanders at a distance of 2400 yards.

Longstreet directed this to be done, and the attack postponed for it. A flat boat and some wire were procured, a ferry fixed up, Law’s and Robertson’s brigades of infantry and Parker’s rifle battery was crossed, and, by working all night of the 24th, it was possible by noon of the 25th to report as ready to open an enfilade fire on Fort Sanders. But the loss of this time and the transfer of this infantry and artillery to the south side of the river were both ill-advised. Our rifle ammunition was defective in quality, our supply of it was quite limited, and the range was too great for effective work under such conditions.

Longstreet felt too the need of the two brigades sent across the river, and, hearing of the coming of Bushrod Johnson’s and Gracie’s brigades, he decided to await their arrival expected the night of the 26th. They brought an effective force of about 2600 men, but they did not actually arrive until the night of the 28th, and were not able to render any service.

That night Longstreet was joined by Gen. Leadbetter, Bragg’s Chief Engineer, who had been at Knoxville during the Confederate occupation, and being the oldest military engineer in the Confederate service, was supposed to be the most efficient. He was a graduate of West Point of 1836, the class ahead of Bragg’s. Coming to Longstreet, as he did, with the prestige of being on the staff of the commanding-general, and especially charged with the decision of all questions of military engineering, it is perhaps not strange that Longstreet was quick to adopt his suggestions, and these, it will be seen, robbed him of most of his few remaining chances of victory.

On Thursday, the 26th, the attack having already been postponed to await the arrival of Johnson’s brigades, Leadbetter and Longstreet rode on a reconnoissance around the enemy’s entire position. Leadbetter pronounced Fort Sanders to be assailable, but expressed a preference for an attack upon Mabry’s Hill. This was the enemy’s extreme right flank, and was undoubtedly the strongest portion of his whole line, besides being the farthest removed and the most inaccessible. In fact our own pickets had been advanced but little beyond Second Creek, and Leadbetter’s opinion was based upon very imperfect and distant views.

It was therefore determined to drive in the enemy’s pickets, and make a better reconnoissance on Friday, the 27th. Meanwhile, so certain was Leadbetter of the advantage of a change in the point of attack, that Parker’s battery was ordered to be withdrawn from the south side of the Holston on Thursday night. On Friday the cavalry was called on to drive in the enemy’s pickets, and Longstreet and Leadbetter, accompanied by the leading generals, made a thorough reconnoissance of our left flank. The attack upon Mabry’s Hill was unanimously pronounced impossible, Leadbetter himself concurring. On the way back the party stopped opposite Fort Sanders, and while watching it with glasses, saw a man cross the ditch in front of the northwest salient, showing the depth of it at that point as less than five feet. This encouraged a hope that the ditch of the fort would not be found a formidable obstacle, and as there was now no alternative, and Leadbetter was urgent against further delay, the attack was ordered at noon on the 28th, this time being necessary to return Parker’s battery to its enfilading position on the south side, whence Leadbetter had had it withdrawn the night before.

At noon the next day all was ready, but the day was rainy, and very unfavorable for artillery practice, so Longstreet again decided to postpone the attack until the next morning, the 29th.

Some howitzers had been raised upon skids, so as to permit fire with small charges at high elevations, as mortars, in order to probe behind the parapets of the fort. It had been ordered that the opening of these mortars should be the signal for the advance of a large number of skirmishers, who should occupy the enemy’s rifle pits within 120 to 250 yards of the fort, enveloping completely its north and west fronts and keeping down the fire, either from its embrasures or parapets. After some practice by the mortars and the sharpshooters, the mortars would suspend, and allow the rifled guns and others to fire to get their ranges. When all had gotten ranges, a rapid fire by both guns and mortars, 34 in all, would begin, concentrated upon the fort as long as seemed necessary. Its cessation would be the signal for the advance of the storming force of two brigades, in columns of regiments, supported by adjacent brigades upon the flanks. If the passage of the ditch was found difficult, the pioneers with spade and picks were expected to rapidly cut small steps in the slopes which would enable the men to swarm over. The sharpshooters and the storming column itself could be relied upon to keep down the fire of the fort on the men in the ditches while this was being done.

The garrison of the fort, as afterward shown, did not exceed 220, including the artillery, and could be overpowered as quickly as they could be reached. It is now to show how all preparations were thrown away and all advantages sacrificed for the illusive merits of a night attack, decided upon by Longstreet after dark on the 28th. Leadbetter was spending the night with him, but whether he suggested or acquiesced was never disclosed.

About 9 P.M. that night I received notice that the plan of attack would be changed and that neither the rifles across the river, the howitzers rigged as mortars, nor any other of the 34 guns arranged to fire on the fort would be used, except to fire a signal. Several days had been spent in preparation for a cannonade, with all our guns concentrated on the small area enclosed by the fort, and now it was all to be given up as well as all to be hoped for from the fire by daylight of a half mile of sharpshooters within from 120 to 250 yards. The fort had no embrasure on its west front and its fire would have to be over the parapets and much exposed.

The advance was intended to be a surprise, and the signal guns were ordered to be fired just before dawn, that the approach of the column might not be visible. There was little time for consultation for it was ordered that at moon rise, about 10 P.M., the enemy’s picket line should be taken and occupied by our sharpshooters, and the troops should be under arms.

Soon after 10 P.M., there was a general advance by our picket lines on both sides of Fort Sanders, and after some two hours of sharp fighting, 50 or 60 prisoners had been taken, the enemy’s pit occupied, and they did not have out a picket 20 yards from the fort. Lt. Benjamin, commanding, feeling sure that the attack would be at daylight, required every man to sleep at his post, and one in every four to keep awake as a sentry. During the night an occasional gun was fired with canister or shell at random from the fort. Federal accounts state that our own artillery was also fired during the night, but this is a mistake. Our own troops were being moved and would have been endangered by such a fire.