THE FALL OF 1864

The Situation in August. Hood appointed to succeed Johnston. Evacuation of Atlanta. Capture of Mobile. Reelection of Lincoln. Battle of Franklin. Sherman’s March. Fort Fisher. Conference at Fortress Monroe. Fort Stedman. Movements of Grant Five Forks, Fort Whitworth and Fort Gregg. Evacuation of Petersburg. Appomattox. Correspondence between Lee and Grant. Conversations with Lee. The Meeting at Appomattox. The Surrender. Visit to Washington. Conversations with Mr. Washburne. Return Home. Record of the Army of Northern Virginia.

GEN. HUMPHREYS writes of the situation in Aug., Mon after the fiasco of the Mine, as follows:1—

“Between this time and the month of March, 1865, several movements of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James were made to the right and to the left, which resulted in the extension of our line of intrenchments in both directions, and caused a corresponding extension of the Confederate intrenchments on our left, and their occupation in stronger force of their intrenchments on the north bank of the James. By this process their lines finally became so thinly manned, when the last movement to our left was made in March, 1865, as to be vulnerable at one or two points, where some of the obstructions in their front had been in a great measure destroyed by the exigencies of the winter.”

In other words, attacks upon our lines were now abandoned for a succession of feints, first upon one flank and them upon the other, by which our lines were extended at both ends to the point of breaking. This point as reached in eight months at one or two places, where the Confederates had been tempted by the severity of the winter to burn the abattis in front of their breastworks. We will not attempt to follow either these efforts of the enemy, or Lee’s aggressive counter-movements, of which there was no lack, though all were attended with much hard fighting.

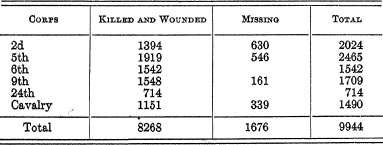

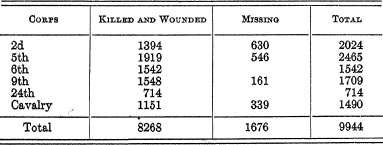

Besides the heavy casualties of these incessant affairs, which followed each other at short intervals from Aug. 1 to Nov. 1, there was daily sharpshooting and much mortar and artillery practice, which helped swell the totals. Confederate reports are entirely lacking, but losses were fully as heavy in proportion to the numbers engaged, as were the Federal losses; for on several occasions Lee was the aggressor and lost heavily. On one, Oct. 7, on the Darbytown road, Field’s division was sent to charge two brigades in breastworks, which proved to be armed with the Spencer magazine-guns. He was quickly repulsed with severe loss, which included Gregg of Texas killed, and Bratton of S.C. wounded. The total Federal casualties for this period, Aug. 1 to Dec. 31, are given as: killed, 2172; wounded, 11,138; missing, 11,311; total, 24,621. The corresponding Confederate losses were probably between 12,000 and 14,000.

It will afford a better view of the situation as a whole to glance at those events referred to by Swinton, where he says:—

“Had not success elsewhere come to brighten the horizon, it would have been difficult to raise new forces to recruit the Army of the Potomac.”

The first and most important of the events resulting in “success elsewhere” was President Davis relieving Joseph E. Johnston of the command of the army opposing Sherman at Atlanta, and appointing Hood to succeed him. This step was taken with great reluctance, and under great popular and political pressure brought by Gov. Brown and Sen. Hill of Ga., who claimed that Johnston intended to surrender Atlanta without giving battle. After many reiterations of such charges, Davis was at length led to give a promise to relieve Johnston if, on being asked for some assurance of his intention to fight, he failed to give it. Gen. Bragg was sent to interview him, and after spending two days with him, wired:—

“He has not sought my advice, and it was not volunteered. I cannot learn that he has any more plan in the future than he has had in the past.”

Davis then wired to Johnston a direct inquiry, as follows:—

“I wish to hear from you as to present situation, and your plan of operations, so specifically as will enable me to anticipate events.”

This was sent July 16, and Johnston replied the same day;—

“. . . As the enemy has double our number, we must be on the defensive. My plan of operations must, therefore, depend upon that of the enemy. It is mainly to watch for an opportunity to fight to advantage. We are trying to put Atlanta into condition to be held for a day or two by the Ga. militia, that army movements may be freer and wider.”

This reply was certainly not specific, and was considered evasive. It will be remembered that, in April, 1862, the relations between the President and Johnston had been strained to the verge of breaking by the general’s reticence as to his plans, and avoidance of interviews, even by galloping to the front on seeing the President approach near the field of Seven Pines. There a crisis was avoided by Johnston’s wound and loss of the command of the army.

Now, a very similar issue had arisen, and with it the old and bitter feelings on each side. On the 17th Adjt.-Gen. Cooper wired Johnson:—

“I am directed by the Sec. of War to inform you that as you have failed to arrest the advance of the enemy to the vicinity of Atlanta, and express no confidence that you can defeat or repel him, you are hereby relieved from the command of the Army and Department of the Tenn., which you will immediately turn over to Gen. Hood.”

To this Johnston replied that the order had been received and obeyed, and added:—

“As to the alleged cause of my removal I assert that Sherman’s army is much stronger, compared with that of Tenn., than Grant’s compared with that of northern Va. Yet the enemy has been compelled to advance much more slowly to the vicinity of Atlanta than to that of Richmond and Petersburg, and penetrated much deeper into Va, than into Ga. Confident language by a military commander is not usually regarded as evidence of competence.”

It is vain to speculate on what might have happened had Johnston been left in command. Had Lee been commander-in-chief, he would not have been relieved, as was indicated by his restoring Johnston to command on his taking that position in February. But it is a fact that Johnston had never fought but one aggressive battle, the battle of Seven Pines, which was phenomenally mismanaged.

On the 20th and 21st, Hood attacked Sherman, but was defeated, and after a month of minor operations was finally, on Sept. 1, compelled to evacuate Atlanta. Meanwhile, a naval expedition, sent under Farragut against Mobile, had captured the forts commanding the harbor of that city on Aug. 23. These two events, the capture of Mobile and Atlanta, following each other within a few days, came at perhaps the period of the greatest political depression of the administration. On Aug. 23, Mr. Lincoln had written on a slip of paper:—

“This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this administration will not be reelected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President-elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration, as he will have secured his election on such grounds that he cannot possibly save it afterward.”

This paper he folded and had the Cabinet put their names on its back.

The victories came like an interposition of Providence, and proved to be the final turning of the balance in the Federal favor. The Democratic party had nominated McClellan on a peace platform, mistaking the general discontent and depression, for a desire for peace at any price. McClellan himself had repudiated the platform, but, as victory now seemed inclining to the Federal banners, all opposition to the administration died out. At the election in Nov., Mr. Lincoln received 212 electoral votes and McClellan but 21.

The attacks which Hood had made upon Sherman on the 20th and 22d had both been judiciously planned and had stood excellent chances of success. The failure in both cases was from want of strict compliance with orders on the part of one of his corps commanders, Gen. Hardee. To trace it further would bring it home to himself for failure to supervise the execution of important orders—a sort of failure from which even the most eminent commanders have never been exempt.

Another and striking example of it attended Hood’s next campaign, this time involving practically a death-blow to his army. Having maneuvered to draw Sherman out of intrenchments at Atlanta by moving upon his communications, he succeeded in drawing him as far north as Dalton, and then crossed into Alabama at Gadsden, where he arrived Oct. 20. Here he had hoped to deliver battle, but Sherman declined to follow, and returned to Atlanta, making preparations for the march to Savannah, upon which he set out Nov. 15.

In this event, Hood’s orders from the President were to follow Sherman and hang upon his rear. But, with the approval of Beauregard, who had been placed in command of the department, Hood decided, instead, to advance upon Nashville, where Thomas commanded, with an inferior force under Schofield, holding the country to the south. Pres. Davis had not imagined that any demonstration Hood could possibly make upon Nashville would be seriously regarded by Grant. The result, however, proved that it was thought to threaten Ky., and it was considered of such grave importance that Grant had threatened to relieve Thomas for delay in attacking Hood. Grant was actually on his way to Nashville perhaps to do this when Thomas won his victory. So much in explanation of Hood’s campaign. The issue at stake was now lost by the non-compliance with orders of Gen. Cheatham, commanding one of Hood’s corps.

Schofield had taken position on the north side of Duck River, opposing Hood’s crossing. Hood loft Lee’s corps to demonstrate against Schofield, while he threw a pontoon bridge across the river three miles above and crossed Cheatham’s and Stewart’s corps which marched to Spring Hill on the Franklin pike, 12 miles in Schofield’s rear, arriving about 3 P.M. This place was held by the 2d division of the 4th corps, about 4000 strong; Hood’s force was about 18,000 infantry. Hood took Cheatham with Cleburne, a division commander, within sight of the pike, along which the enemy could now be seen retreating at double-quick, with wagons in a trot, and gave explicit orders for an immediate attack and occupation of the pike. Similar orders, too, were given to Stewart’s corps, and when Hood found later that nothing was being done, he sent more messages by staff-officers, which also failed of effect. The head of Schofield’s infantry arrived about nine o’clock and passed unmolested, except by some random picket shots to which they made no reply. Both Confederate divisions had bivouacked within gunshot of the pike, but no effort was made to occupy it or to cross it. Undoubtedly, here Hood should have ridden to the front and led the troops into action himself. In his book, he calls the opportunity “the best move in my career as a soldier.” A few days after, Cheatham frankly admitted his delinquency. It was rumored that both he and Gen. Stewart had that evening absented themselves from their divisions. Both had been often distinguished for gallantry, and Hood now overlooked it, believing it had been a lesson not to be forgotten. Nevertheless, it proved the death-blow to Hood’s army.

On the next day, Schofield took a strong position at Franklin for the protection of his wagon-trains, resting both flanks on the Harpeth River across a concave bend. His intrenched main line was but a mile in length. It was well protected with abattis, and, 280 yards in front, an entire division, Wagner’s of the 4th corps, held an advanced line, with its flanks drawn back nearly to the main line, and also well protected by abattis. His infantry, about 23,000, was a little more than Hood’s and was ample to man both lines, and to hold a strong reserve in a well sheltered position close in the rear. One of his infantry brigades, Casement’s, was armed with magazine breech loaders. The ground in front was mostly level and open pasture-land, and batteries across the Harpeth could fire upon the approaches.

To assault was a terrible proposition to troops who, during Johnston’s long retreat, had been trained to avoid charging breastworks. But Hood saw no alternative, since he had lost the one opportunity of the campaign at Spring Hill the night before. For Schofield was now within a day’s march of Nashville. He ordered the attack, and for the credit of his army it must be said that officers and men responded valiantly, and went down to defeat in a blaze of glory. Over 10 per cent of the force engaged were killed outright on the field, over 20 per cent were carried to hospitals with severe wounds, and as many more suffered less severe wounds or were captured. The loss of general officers was unparalleled on either side in any action of the war. Cleburne, Gist, Adams, Strahl, and Granberrty were killed; Brown, Carter, Manigault, Quarles, Cockrell, and Scott were wounded, and Gordon was captured. Fifty-three regimental commanders were killed, wounded, or captured. The result might have been different, but for three handicaps: 1. Hood, most unwisely, did not precede his charge with a severe cannonade, because the village of Franklin was but a half-mile in rear of his line. The enemy’s position was quite crowded, and all his lines were subject to enfilade. It would have severely shaken the enemy, and with little danger to non-combatants, which they could not avoid. 2. The action was not begun until 4 P.M. The sun set at 4.50 P.M. and darkness prevented Hood from getting in two of Lee’s divisions. There was no moon. 3. The presence on the field of Casement’s brigade with magazine breech loaders. It was said by a correspondent that never before had men been killed so fast as they were during this charge by the fire of this brigade. The action was hand to hand all along the enemy’s main line. It was carried for quite a space, at one point, but was restored by a charge of the reserve. At some points men were dragged across the parapets and captured. The battle continued with violence until 9 P.M. and firing was kept up until 3 A.M., when the enemy withdrew from the field, leaving his dead and wounded. Schofield’s losses were: killed, 189; wounded, 1033; missing, 1104; total 2326. Hood left 1750 dead on the field and 3800 in hospitals. The slightly wounded and prisoners were about 2000.

His losses in the battle of Franklin made it impossible for Hood to attack at Nashville, but he hoped to fortify and threaten until he was attacked, and then to gain a victory. What a vain hope! Efforts were being made to bring troops from Texas across the Mississippi, which also, of course, proved vain. They never even started. His force was now reduced to about 18,000 infantry and 5000 cavalry, with which he took position before Nashville on Dec. 2. Here he intrenched himself and awaited Thomas’s attack, which the latter delayed until Dec. 15. By this date he had accumulated a force of over 53,000 men. With these he attacked on the 15th, but with little success and with severe losses at points where he assailed Hood’s intrenchments.

On the 15th, the Federals renewed their assaults and during the morning were again repulsed. About 3 P.M., they massed a large force under cover behind a hill about Hood’s left centre, and under cover of a heavy fire of artillery made a gallant charge and carried Hood’s line, which, seeing the disaster, broke in all directions, and all efforts to rally it failed.

During the night, Hood withdrew, losing 54 guns and 4500 prisoners. There was no return made of his casualties, but he reported them as “very small.” Thomas reported: killed, 387; wounded, 2562; missing, 112; total, 3061. Hood made good his retreat to Tupelo, Miss., where his army rested for reorganization on Jan. 10, 1865. In the spring, it was transferred to N.C., where it served under A. P. Stewart and, about 7000 strong, was included in Johnston’s surrender. The battle of Franklin had proved its death-blow.

Besides the loss of Atlanta and the destruction of Hood’s army, there remains a third sequence of the change of commanders which deserves notice among the “successes elsewhere,” preparing the ground for Grant when he again became able to inaugurate a campaign. This was the unopposed march of Sherman from Atlanta to Savannah between Nov. 15 and Dec. 25, with the capture of Savannah on the latter date. It was preceded by the deliberate burning of every house in Atlanta. “Not a single one was spared, not even a church.” This was excused on the ground that “War is Hell.” It depends somewhat upon the warrior. The conduct of Lee’s army in Pa. presents a pleasing contrast.

It had been hoped that the few troops which could be gathered in Ga., aided by the militia of the State, and by 13 brigades of Confederate cavalry under Wheeler, might effectively harass and delay such a march, but all such expectations proved utterly vain. Though little was said in the press at the time, and our public speakers belittled the achievement, there is no question that the moral effect of this march, upon the country at large, both at the North and the South and also upon foreign nations, was greater than would have been the most decided victory. Already it cast the ominous shadow of Sherman’s advance up the coast in the coming spring.

In this connection, there now began demonstrations against Wilmington, which was the last port of the Confederacy holding out opportunities to blockade runners. These came in under the protection of Fort Fisher at the mouth of the river 20 miles below the city. The fort was a formidable one, mounting 44 guns, and had a garrison of 1400 men under Col. Lamb. A military and naval expedition set out against it on Dec. 13, 1864, under Gen. Butler and Adm. Porter in a fleet of 50 war vessels and 100 transports carrying 6500 infantry. The fleet was the largest ever assembled under the Federal flag, and it had been specially intended by Grant that the infantry force should be commanded by Gen. Weitzel. It was never contemplated that Butler should even accompany it. In the expressive language of modern slang he had not only “butted in,” and had taken the command from Weitzel, but had devised a new mode of attack upon Fort Fisher. This was to be a disguised blockade runner loaded with 215 tons of gunpowder to be run at night close to Fort Fisher and exploded. It was supposed that this would put the whole fort hors de combat. Gen. Delafield, chief engineer, submitted to the War Department a report on destructive effects of explosions of gunpowder in open air, indicating their very limited range. Butler was notoriously a military charlatan, who had been forced upon Grant as commander of the Army of the James by political considerations. During all the summer campaign, he knew and felt his importance, and had been able even successfully to bully Grant himself, who was already under sharp criticism for his terrible losses in battle, and for the rumors in the army of his intemperance.

Early in July, after some preliminary correspondence, indicating a doubt how Butler would relish any interference with himself, Halleck issued an order assigning the troops under him to the command of W. F. Smith, and sending Butler to Fortress Monroe. On receipt of this order, he said to his staff, who were near, “Gentlemen, this order will be revoked to-morrow.” The next day, clad in full uniform, he called at Grant’s headquarters, where he found Mr. Dana, Asst. Sec. of War. Gen. James H. Wilson, in a memoir on the Life and Services of W. F. Smith, gives the following account of the interview:—

“Dana describes Butler as entering the general’s presence with a flushed face and a haughty air, holding out the order relieving him from command in the field, and asking: ‘Gen. Grant, did you issue this order?’ To which Grant, in a hesitating manner, replied: ‘No, not in that form.’ Dana, perceiving at this point that the subject under discussion was likely to be unpleasant, if not stormy, at once took his leave, but the impression made upon his mind by what he saw while present was that Butler had in some measure ‘cowed’ his commanding officer. What further took place neither he nor Mr. Dana has ever said. Butler’s book, however, contains what purports to be a full account of the interview, but it is to be observed that it signally fails to recite any circumstance of an overbearing nature.”

Not only was the order promptly revoked by Special Orders No. 62, July 19, but Butler’s command on the field was extended to include the newly arrived 19th corps, and this disposition of command was still in force when Butler “butted in” to the Fort Fisher expedition, taking his powder boat with him, regardless of Delafield’s discussion of the value of powder boats.

The boat was towed into position by Commander Rhind of the Navy who reported placing it “within 300 yards of the northeast salient of Fort Fisher,” which bore “west southwest a half west” about midnight of Dec. 23, 1864. It was fired by several lines of Gomez fuse running through the mass of powder and ignited by several devices arranged to act an hour and a half after the ship was deserted. The explosion occurred at 2 A.M., and was supposed by the garrison of the fort to be the accidental explosion of a Federal gunboat. Not the slightest damage was done to the fort, whose garrison remained in ignorance of Butler’s plans until published afterward.

On the 24th and 25th, the fort was subjected to a terrific bombardment at the rate of 40 to 50 shells per minute for hours at a time, until the fleet had practically exhausted its ammunition. It had not silenced the fort nor materially damaged it, which, being reported by the land forces who had been put ashore, they reembarked without assaulting, on the night of the 26th, and the next day the expedition returned to Fortress Monroe. The casualties in the fort from the fire of the ships were 61, and a greater number were suffered in the fleet from the 662 shots fired by the fort.

Another and a still larger expedition was soon gotten together and despatched against Fort Fisher, but, though his own campaign was still in abeyance, the political situation was now so improved by the “successes elsewhere” that Grant was no longer afraid to exercise his authority, and on Jan. 4, he wrote to Halleck demanding Butler’s official head. With a celerity indicative of the pleasure with which both Halleck and Lincoln complied with the request, it was presented to him. On Jan. 7, in General Orders No. 1, “By direction of the President,” Maj.- Gen. Butler was relieved from command and ordered to repair to Lowell, Mass.

On Jan. 5, a new expedition, under the command of Porter and Gen. Terry, set sail, carrying about 9500 infantry and a heavy siege-train. It arrived before Fort Fisher and opened fire on Jan. 13, in even greater force than on the previous occasion. A land force of about 7000 infantry was at hand for its defense. Mr. Davis sent Bragg to command it, who made no effort to prevent the enemy’s landing. It might have been difficult to prevent him, but to make no effort brought complaint and discouragement. The bombardment was, on this occasion, kept up without intermission day or night, and, instead of being general, was concentrated upon the land defenses. On the afternoon of the second day, the palisades and guns of those defenses being destroyed and a breach opened, two assaults were made about 3 P.M., one by Ames’s division of the 23d corps, about 4500 strong, and one by 2000 sailors and marines from the fleet under Capt. Breese. The latter assaulted the breach, but were repulsed with severe loss. The infantry, passing around and through the palisades, made a lodgment between the traverses, and after seven hours’ fighting possessed the fort. When Bragg took command of the land forces, Whiting, who had commanded the whole post before, took command of the fort. He was mortally, and Col. Lamb desperately, wounded in the defense. The loss of the infantry assaulting column was 110 killed, 536 wounded.

During the winter, the Confederate lines about Petersburg had been constantly extended at both ends, it has been already explained how. The troops were extended with them until it was about 37 miles by the shortest routes from our extreme left on White Oak Swamp below Richmond on the north side, to our extreme right below Petersburg. Lee’s force at this time was about 50,000 and Grant’s about 124,000. Humphreys gives the following brief statement of the Confederate condition:—

“The winter of ‘64-65 was one of unusual severity, making the picket duty in front of the intrenchments very severe. It was especially so to the Confederate troops with their threadbare, insufficient clothing and meager food. Meat they had but little of, and their Subsistence Department was actually importing it from abroad. Of coffee or tea or sugar, they had none except in the hospitals.

“‘It is stated that in a secret session of the Confederate Congress the condition of the Confederacy as to subsistence was declared to be:—

‘That there was not meat enough in the Southern Confederacy for the armies it had in the field,

‘That there was not in Va. either meat or bread enough for the armies within her limits,

‘That the supply of bread for those armies to be obtained from other places depended absolutely upon keeping open the railroad connections of the South,

‘ That the meat must be obtained from abroad through a seaport,

‘ That the transportation was not now adequate, from whatever cause, to meet the necessary demands of the service. . . .’

“The condition of the deserters who constantly came into our lines during the winter appeared to prove that there was no exaggeration in this statement.”

In addition to the scarcity of provisions, there was also threatened a deficiency of percussion caps. The supply for the campaign of 1864 had been maintained only by cutting up the copper stills of the country, but they were now exhausted and there was no more copper in sight.

Col. Taylor, in Four Years with Lee, writes that during the last 30 days before Petersburg:—

“The loss to the army by desertion averaged a hundred men a day. . . . The condition of affairs throughout the South at that period was truly deplorable. Hundreds of letters addressed to soldiers were intercepted and sent to army headquarters, in which mothers, wives, and sisters told of their inability to respond to the appeals of hungry children for bread, or to provide proper care and remedies for the sick, and in the name of all that was dear appealed to the men to come home and rescue them from the ills which they suffered and the starvation which threatened them. Surely never was devotion to one’s country and to one’s duty more sorely tested than was the case with the soldiers of Lee’s army during the last year of the war.”

Early in Feb., there occurred the last of the many affairs on our right flank. Grant had found that we were still hauling supplies from the Weldon R.R. and had sent Gregg’s cavalry to destroy it, and tear it up for 40 miles south, and the 2d and 5th corps were sent across Hatcher’s Run to guard their rear. Lee, hearing of the Federals outside of their intrenchments, sent three divisions under Mahone, Evans, and Pegram to attack them. There was sharp fighting for two days without material success on either side. The Federal losses were 1474 and probably the Confederate were 1000. Among them, unfortunately, was Gen. Pegram, whose loss was universally deplored. Col. Taylor, under date of Dec. 4, has noted the loss of another brilliant and popular young officer who had been a classmate of Pegram’s at West Point in 1854, as follows:—

“Gen. Gracie, who showed such tact in getting Gen. Lee to descend from a dangerous position, was killed near the lines a day or so ago. He was an excellent officer, had passed through many hard-fought battles, escaped numberless dangers, and was finally killed while quietly viewing the enemy from a point where no one dreamed of danger.”

Col. Taylor, in a letter, describes the incident referred to as follows:—

“Gen. Lee was making an inspection along the line occupied by Gen. Gracie’s troops; the fire of the enemy’s sharpshooters was uncomfortably accurate along there and the orders were against needless exposure. To get a good view Gen. Lee mounted the parapet or stepped out in front of the works. Of course all who saw it realized his danger, but who was to direct his attention to it? Gen. Gracie at once stepped to his side. The minnies whistled viciously. Gen. Lee, oblivious to his own danger, quickly realized Gen. Grade’s and immediately removed from the point of danger. That is all but it showed tact on the part of the latter.”1

I have already said that the fall of 1864 was the period of the war when the Confederate authorities might have made peace with greatest advantage to their people. Had they then offered a return to the Union, they might have secured liberal compensation for their slaves and generally more liberal terms financially and politically than at any other period of the contest. What these concessions might have been was suggested in the conference held at Fortress Monroe on Jan. 30, between Messrs. Lincoln and Seward, and the commissioners sent by Mr. Davis, Messrs. Stephens, Hunter, and Campbell. After this conference adjourned, without coming to any agreement, there were rumors that Mr. Lincoln had offered to pay the South $400,000,000 in bonds as compensation for the slaves, if the South would return to the Union. This was denied by some of Mr. Davis’s cabinet, and the discussion brought out informal statements which Mr. Lincoln had made in the conversation which had taken place.

One was:—

“Take a sheet of paper and let me write at the top Union, and you may fill in the rest to suit yourselves.”

To this Mr. Stephens had to reply that the power to write that word was the single power which had been denied the commission.

Next, Mr. Lincoln said that he had always felt that slavery having had the sanction of the government as a whole, it was unfair that the whole financial loss of its abolition should be thrown upon the South; that he had always felt ready to vote bonds to compensate her for this loss, and that he had heard as much as $400,000,000 suggested for this purpose.

There was no formal proposition made, for the Conference never reached that stage, but it is well known that until the day of his death, Mr. Lincoln cherished a desire to see the South compensated for the loss of her slaves, and that on Feb. 5, immediately after the failure of the Fortress Monroe Conference, he submitted to his cabinet a proposition to offer the South $400,000,000 in six per cent bonds in payment for peace with the abolition of slavery. His cabinet unanimously disapproved it, to his surprise and chagrin, whereon he dropped the matter, saying sadly, “You are all opposed to me.”1

“Few cabinet secrets were better kept than this,” Nicolay says, but the diary of Sec. Welles refers to it as follows:—

“The President had matured a scheme which he hoped would be useful in promoting peace. It was a proposition for paying the expense of the war for 200 days, or $400,000,000, to the rebel States to be for the extinguishment of slavery, or for such purpose as the States were disposed. This in a few words was the scheme. It did not meet with favor, but was dropped. . . .”

Early in March, Sherman’s army moved into N.C. where it was confronted by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, recalled by the Confederate Congress to command the army composed of the garrisons of Savannah and Charleston, and the remnants of the army of Hood which had been brought over from Tupelo, Miss. It was plain that Lee would soon be forced to abandon Richmond and Petersburg, and take advantage of his interior lines to unite with Johnston, and endeavor to crush Sherman before he could unite with Grant. Before undertaking this, which was felt to be an almost impossible task, however, he determined upon one last effort to break up Grant in his immediate front, in spite of all of his fortifications. He selected for his point of attack Fort Stedman, about a mile from the Appomattox River on Grant’s right, and assigned Gordon to command the assault which was to be made Mar. 25. A surprise was relied on to secure Fort Stedman. Three columns of 100 men each, with local guides, were to seize what Gordon took to be three redoubts commanding Stedman on each side; a division was to follow them, and, through the gap thus made, the lines were to be swept in both directions and a force of cavalry was to ride and destroy the pontoon bridges across the Appomattox, and to raid City Point.

Taking advantage of an order allowing deserters to come in with their arms, several pickets were captured, the trench guard rushed, the fraise and abattis cut quickly by a strong pioneer party, and Fort Stedman was assaulted and occupied with two adjacent batteries. But the three “redoubts” were found to be only some old open lines at commanding points now unoccupied. Federal infantry presently came in force and killed or captured all of the three columns sent under a misapprehension very likely to occur where earthworks have to be guessed at from imperfect observation. Field’s division, which had been ordered over by rail from the north side, was delayed by the breaking down of the train. The column which had taken Fort Stedman was caught like rats in a trap. Humphreys writes:—

“The cross-fire of artillery and infantry on the space between the lines prevented the enemy from escaping and reinforcements from coming to them. Many were killed and wounded trying to get back to their own lines; 1949 prisoners, including 71 officers and 9 stand of colors, fell into Gen. Parke’s hands. His loss was 494 killed and wounded, and 523 missing, a total of 1017.”

While this fighting was going on, the other Federal corps were ordered to feel the lines in their fronts, it being hoped they might find some weak spots from which men had been drawn for Gordon’s attack. Much sharp fighting resulted at many points, the total casualties for the day reaching 2000 for the Federals and 4000 for the Confederates. These attacks, however, everywhere failed entirely of their purpose except at a single point, on the lines of the 6th corps, about nine miles to our right from the point of Gordon’s attack. Here, opposite a fort called Fort Fisher, our abattis had been weakened to get in fire wood from the front, and here the enemy were able to make a lodgment within our intrenched picket-line. When Grant’s general assault was made at 4 A.M., April 2, this was the spot, and the only one, where at first it was successful. Humphreys states that it was—

“Through openings made by the enemy for his convenience of access to the front, Gen. Wright told me that this was the weakest part of all the line he saw, and the only point where it could have been carried. His loss in killed and wounded was 1100, all of which occurred in the space of 15 minutes.”

Apprehensive now that Lee. might abandon Petersburg and Richmond at any moment, Grant determined to delay no longer, talking the initiative in moving around his right flank. His effective force, by his latest returns, was 101,000 infantry, 9000 artillery, 14,700 cavalry, total, 124,700, with 369 guns. Lee’s forces by his latest return, Feb. 28, were 46,000 infantry, 5000 artillery, and 6000 cavalry, total 57,000, from which 3000 should be deducted for desertions in March. In N.C., Sherman was about Goldsboro with about 100,000, against which Johnston in front of Greensboro had, perhaps, 25,000. There was really no need that Grant should have hurried himself, for, though by all the maxims of strategy, Lee should now unite with Johnston and both attack Sherman, his deficiencies in transportation were so great that no such movement was practicable.

On March 27, Sheridan with two divisions of his excellent cavalry with their magazine carbines had rejoined the army, and Grant began to transfer his forces to his extreme left. A single division only, Devens of the 24th corps, was left north of the James. Two divisions of the 25th corps under Weitzel held the Bermuda Hundreds lines. All the rest of the infantry, about 90,000 muskets and the whole of the cavalry, thoroughly organized and abundantly equipped with transportation for rapid motion, on March 28 only awaited Grant’s word to launch themselves upon Lee’s communications.

On this occasion, Grant narrowly avoided one mistake of previous campaigns made, not only by himself in May, 1864, but by Hooker in May, 1863, and by Lee in June, 1863. He kept his cavalry moving and acting with his infantry instead of sending it off on a raid, having suspended on the 29th orders of the previous day to move against the railroads. It is noticeable, too, that Grant, on this occasion, concentrated practically his entire force in the attack upon our right, whereas, in the fall, he had never attacked upon one flank without some demonstration, at least, upon the other.

On the 30th, Wilcox’s division on the north, and Hoth’s on the south, of Hatchers Run had sharp affairs with the approaching Federals, whom they went out to meet in some cases, but were finally driven back within their lines. The Federal losses for the day were 1780. There are no returns for ours.

Meanwhile, Lee was bringing up Pickett’s and Johnson’s divisions of infantry, about 6600 men, and two of Lee’s divisions of cavalry, about 5760 men, for an expedition against Sheridan. They attacked him on the 31st, and drove him back in much confusion nearly to Dinwiddie C. H. Night ended the fighting, with Pickett so far in advance that he would have been cut off by Warren’s corps, during the night, had he waited until morning. But he fell back, and took position in the morning at Five Forks, four miles from our right at Burgess Mills.

Here he made the fatal mistake of halting and proceeding to intrench, as well as the time and the scarcity of intrenching tools would permit. He was four miles away from where other troops could help him or they could be helped by him. He should never have stopped until he had connected with our right flank.

Longstreet writes:—

“The position was not of Pickett’s choosing but of his orders, and from his orders he assumed that he would be reinforced.”

As it was, in the morning, April 1, Sheridan, reinforced now by the 5th corps, some 15,000 men, followed, and massing a force of cavalry on Pickett’s right, with the 5th corps he turned his left flank and routed him, capturing, as stated by Warren, 3244 men, 11 colors, and 4 guns, with a loss of only 634 men. The Federal Gen., Winthrop, was killed, and on the Confederate side Col. Pegram, a brother of the Gen. Pegram killed Feb. 6, and highly distinguished as an artillerist.

This battle was fought between four and six in the afternoon, and Humphreys notices a peculiar phenomenon of acoustic shadows, such as has been spoken of before in telling of other battles. He writes:—

“A singular circumstance connected with this battle is the fact that Gen. Pickett was, all of this time and until near the close of the action, on the north side of Hatchers Run where he had heard no sound of the engagement, nor had he received any information concerning it.”

The distance was but little over a mile, and Fitz-Lee and Pickett were in company. Neither were on the field until the action was decided.

Although this action was a complete success, after it was over Warren was removed from the command of the 5th corps by Sheridan, under charges of which Warren was afterward fully acquitted by a Court of Inquiry.

When Grant heard at 9 P.M. of Sheridan’s success, he was assured that he must now have Lee’s long lines stretched to near the breaking strain, and that the time had come when he could renew his assaults, suspended since the occasion of the mine. With his usual promptness, he ordered the 2d corps, which was near him, south of Hatchers Run, to feel our works in its front at once. The other corps, stretching back to Petersburg, were ordered to cannonade our lines daring the night, and, at his favorite hour of 4 A.M., to assault all the soft spots, of which, for two or three days, each corps commander had been ordered to make a study.

The midnight demonstration by the 2d corps waked a heavy fire of musketry and artillery, but produced no other results. The assault of the 6th corps at dawn, however, under Wright, was made at the point where our abattis had been weakened, and the enemy had made a lodgment, on Mar. 25. As before mentioned, here their assault was entirely successful, after incurring a loss of 1100 men. They then turned to the left and swept the Confederate line to its extremity. At the crossing of the Jerusalem Plank road, Parke got possession of an advanced line, with 12 guns and 800 prisoners, but he failed to carry our main line in the rear, and the fighting was kept up all day. At all other points, the morning assaults were repulsed.

After capturing all the works to the south and west, the enemy now turned toward Petersburg, where two isolated works, Forts Gregg and Whitworth, about 300 yards apart, stood about 1000 yards in front of our main line of intrenchments. The rear of Fort Gregg was closed with a palisade, and its ditch was generally impassable. On the right flank, however, a line to connect with Whitworth had been started, and hero the unfinished ditch and parapet gave a narrow access to the parapet of Gregg. It was by this route that the enemy finally reached it. It was defended by two guns of the Washington artillery under Lt. McElroy, and Lt.-Col. Duncan, with the 12th and 16th Miss., 214 men in all. Fort Whitworth was open at the gorge and was held by three guns of the Washington artillery and the 19th and 48th Miss. until the final charge was being made upon Fort Gregg, when, by Lee’s order, the garrison was withdrawn.

The defense of Fort Gregg was notable, as was also the attack. The Federal forces were evidently feeling the inspiration of success and the Confederates the desperation of defeat. Several attacks by Foster’s division, of the 24th corps, were repulsed. The last, aided by two brigades of Turner’s division (while the 3d brigade advanced upon Whitworth) swarmed over the parapet of Gregg and captured, inside, the two guns with two colors. Of the garrison, 55 were killed, 129 were wounded, and only 30 were found uninjured of the 214. Gibbon’s loss was 122 killed, 592 wounded, total, 714.

Lee and Longstreet, from the main line of intrenchments, witnessed the gallant defense of Fort Gregg and its final fall. A. P. Hill, aroused by the terrific cannonade and musketry at daylight and riding to join his troops, had been killed by some stragglers of the 6th corps, which, as has been told, had carried our lines and penetrated far inside of them. When Lee, on the night of April 1, had heard of the disaster to Pickett at Five Forks, he had wired for Longstreet with Field’s division. This left only Kershaw’s division and the local troops to hold Richmond, but Weitzel’s force had already been so reduced that no aggressive idea was left him. Had he known of the withdrawal of Field’s division, he might have been tempted to make an effort to take the city. On Longstreet’s arrival in Petersburg, his troops were hurried to the intrenchments, whence they saw the gallant defense made by Fort Gregg, which had been done under the assurance that “Longstreet is coming. Hold for two hours and all will be well.”

When these saw the forts captured, they expected nothing else but that the heavy blue columns and long lines would now move to crush them. But the lesson of Fort Gregg had not been thrown away. Grant recognized that Lee must retreat during the night, and that from his own position he would have the advantage in the start, and he preferred to order things prepared for the march westward in the morning. Lee had already advised Mr. Davis of the necessity of abandoning the lines that night, and, having noted Grant’s pause after the capture of Fort Gregg, now, about 3 P.M., he issued the formal orders for the evacuation in time to have the troops begin to move at dark.

My headquarters had been on the Richmond side for some months, and my duty included the command of Drury’s and Chaffin’s bluffs, and the defense of the river. It happened that on April 2, I had prepared several torpedoes to be placed in the river that night, and early in the morning I went down into the swamp and was detained until late in the afternoon, when the orders of evacuation reached me. Part of my command was to cross the river at Drury’s Bluff and part at Richmond. After giving necessary instructions, I rode into Richmond, and took my post at the bridge to see my batteries go by. Many accounts have been given of the scenes in Richmond that night, and I will not refer to them.

The freight depot of the Danville Road was close by the bridge, and I walked into it and saw large quantities of provisions and goods which had evidently run the blockade at Wilmington I treated my horse to an English bridle and a felt saddle-blanket, and I hung to a ring on my saddle a magnificent side of English bacon, which proved a great acquisition during the next few days. These provisions were intended for Lee’s army, and had been sent to Amelia C. II. from Danville, the train being ordered to come on to Richmond to take off the personnel and property of the government. Unfortunately, the officer in charge of it misunderstood his orders and came on without unloading at Amelia. Near my station in the street, a cellar door opened in the sidewalk, and while I waited for my batteries a solitary Irish woman brought many bales of blankets from the freight depot in a wheelbarrow and tumbled them in to the cellar. Many fires were burning in the city, and a canal-boat in flames came floating under the bridge at which I stood. I could not see by what agency, but it was soon dragged away. The explosions of our little fleet of gunboats under Admiral Semmes at Drury’s Bluff were plainly heard and the terrific explosion of the arsenal in Richmond. About sunrise, my last battalion passed and I followed, taking a farewell look at the city from the Manchester side. The whole river front appeared to be in flames. Its formal surrender was made to Weitzel at 8.15 A.M.

We marched 24 miles that day and bivouacked at night in some tall pine woods near Tomahawk Church. I had barely gotten supper when I was ordered to join two engineers being sent to find a wagon route for our guns and trains to an overhead railroad bridge across the Appomattox River. We travelled all night in mud and darkness, waking up residents to ask directions, but we finally got the whole column safely across the railroad bridge and went into camp near sundown about three miles from Amelia C. H.

The next morning we passed through the village, where we should have gotten rations, but they did not meet us. They had gone on to Richmond and been destroyed there, as has been told. Here a few of the best-equipped battalions of artillery were selected to accompany the troops, while all the excess was turned over to Walker, chief of the 3d corps artillery, to take on a direct road to Lynchburg. About 1 P.M., with Lee and Longstreet at the head of the column, we took the road for Jetersville, where it was reported that Sheridan was across our path and Lee intended to attack him. We were not long in coming to where our skirmish line was already engaged, and a long conference took place between the generals and W. H. F. Lee in command of the cavalry. It appeared that the 2d and 6th corps were in front of us, but might be passed in the night by a flank march. We countermarched a short distance, and then turning to the right, we marched all night, passing Amelia Springs, and arrived at daylight at Rice’s Turnout, six miles west of Burkesville.1 Here I was ordered to select a line of battle and take position to resist attack, and here we waited for the remainder of the army to come up and pass us, but we waited in vain.

While the 2d corps had closely pressed the rear of the column all day, the cavalry and the 6th corps had struck its flank under Ewell at Sailor’s Creek. Besides Kershaw’s division, this force comprised no veteran soldiers, but the employees of the departments under Custis Lee, the marines and sailors of our little fleet under Admiral Tucker, and the heavy artillerists of Drury’s and Chaffin’s bluffs, under Col. Crutchfield and Maj. Stiles. This force, though largely composed of men who had never before been under fire, surprised the enemy with an unexpected display of courage, such as had already been shown at Fort Stedman and Fort Gregg, and would still with flashes illuminate our last days. It formed line of battle on the edge of a pine wood, in full view of two lines of battle in open ground across a little stream. It had no artillery to make reply, and it lay still while other Federal infantry was marched around them, and submitted to an accurate and deliberate cannonade for 20 minutes, followed quickly by a charge of the two lines. Not a gun was fired until the enemy approached within 100 yards, showing handkerchiefs as an invitation to the men to surrender. Then two volleys broke both of their lines, and the excited Confederates charged in pursuit of the fleeing enemy, but were soon driven back by the fire of the guns. A second charge of the Federals soon followed, in which the two lines mingled in one promiscuous and prolonged mêlée with clubbed muskets and bayonets, as if bent upon exterminating each other individually. Gen. Custis Lee in his official report thus describes the ending:—

“Finding . . . that my command was entirely surrounded, to prevent useless sacrifice of life, the firing was stopped by some of my officers aided by some of the enemy’s, and the officers and men wore taken as prisoners of war.”1

Toward noon, the enemy began to appear in our front at Rice’s Turnout, and made demonstrations, but were easily held off by the artillery. Meanwhile, Lee had become very anxious over the non-arrival of Anderson’s command (the remnants of Pickett’s and Johnson’s divisions), and at last rode to the rear to investigate. He did not return until near sundown and with him came fuller news of the battle at Sailor’s Creek in which Anderson was also involved. Our loss had been about 8000 men, with six generals—Ewell, Kershaw, Custis Lee, Dubose, Hunton, and Corse—all captured.

One notable affair had taken place on this date, between a small force under Gen. Read, sent ahead by Ord to burn the High Bridge on the Lynchburg road, and Dearing’s and Rosser’s cavalry. The expedition consisted of two regiments of infantry and about 80 cavalry. They had gotten within a mile of the bridge, when our cavalry, in much larger force, attacked them. Humphreys writes:—

“A most gallant fight ensued in which Gen. Read, Col. Washburn, and three other cavalry officers were killed. After heavy loss the rest of the force surrendered. Gen. Dearing, Col. Boston, and Maj. Thompson of Rosser’s command were among the killed.”

About sundown, the enemy at Rice’s showed a disposition to advance, and Lee soon gave orders to resume our retreat. In the morning we might have gone on toward Danville, but now we turned to the right and took the road to Lynchburg. I remember the night as one peculiarly uncomfortable. The road was crowded with disorganized men and deep in mud. We were moving all night and scarcely made six miles. About sunrise, we got to Farmville and crossed the river on a bridge to the north side of the Appomattox, and here we received a small supply of rations.

Here we found Gen. Lee. While we were getting breakfast, he sent for me and, taking out his map, showed me that the enemy had taken a highway bridge across the Appomattox near the High Bridge, were crossing on it, and would come in upon our road about three miles ahead. He directed me to send artillery there to cover our passage and, meanwhile, to take personal charge of the two bridges at Farmville (the railroad and the highway), prepare them for burning, see that they were not fired too soon, so as to cut off our own men, nor so late that the enemy might save them.

While he explained, my eyes ran over the map and I saw another road to Lynchburg than the one we were taking. This other kept the south side of the river and was the straighter of the two, our road joining it near Appomattox C. H. I pointed this out, and he asked if I could find some one whom he might question. I had seen at a house near by an intelligent man whom I brought up and who confirmed the map. The Federals would have the shortest road to Appomattox station, a common point a little beyond Appomattox C. H. Saying there would be time enough to look after that, the general folded up his map and I went to look after the bridges.

As the enemy were already in sight, I set fire to the railroad bridge at once, and, having well prepared the highway bridge, I left my aide, Lt. Mason, to fire it on a signal from me. It was also successfully burned. In the End of an Era by John S. Wise, he has described an interview occurring between his father, Gen. Wise, and Gen. Lee at Farmville at this time, which I quote:—

“We found Gen. Lee on the rear portico of the house I have mentioned. He had washed his face in a tin basin and stood drying his board with a coarse towel as we approached. ‘Gen. Lee,’ exclaimed my father, ‘my poor brave men are lying on yonder hill more dead than alive. For more than a week they have been fighting day and night, without food, and, by God, Sir, they shall not move another step until somebody gives them something to eat.’

“‘Come in, General,’ said Gen. Lee, soothingly. ‘They deserve something to eat and shall have it; and meanwhile you shall share my breakfast.’ He disarmed everything like defiance by his kindness. . . . Gen. Lee inquired what he thought of the situation. ‘Situation?’ said the bold old man. ‘There is no situation. Nothing remains, Gen. Lee, but to put your poor men on your poor mules and send them home in time for the spring ploughing. This army is hopelessly whipped, and is fast becoming demoralized. These men have already endured more than I believed flesh and blood could stand, and I say to you, Sir, emphatically, that to prolong the struggle is murder, and the blood of every man who is killed from this time forth is on your head, Gen. Lee.’

“This last expression seemed to cause Gen. Lee great pain. With a gesture of remonstrance, and oven of impatience, he protested. ‘Oh, General, do not talk so wildly. My burdens are heavy enough! What would the country think of me, if I did what you suggest?’

“‘Country be d—d,’ was the quick reply. ‘There is no country. There has been no country, General, for a year or more. You are the country to those men. They have fought for you. They have shivered through a long winter for you. Without pay or clothes or care of any sort their devotion to you and faith in you have been the only things that have held this army together. If you demand the sacrifice, there are still left thousands of us who will die for you. You know the game is desperate beyond redemption, and that, if you so announce, no man, or government, or people will gainsay your decision. That is why I repeat that the blood of any man killed hereafter is on your head.’ Gen. Lee stood for some time at an open window looking out at the throng now surging by upon the roads and in the fields, and made no response.”

Well might Lee say, “My burdens are heavy enough!” Gen. Wise had in no way exaggerated them.

Poague’s battalion of artillery had gone ahead to the intersecting road Lee had mentioned, and Mahone’s division (now assigned to our corps) supported by Poague’s guns, took a good position and began to fortify. They held the position all day, being charged in the afternoon, repulsing the enemy and charging in turn. They captured the colors of the 5th N.H., and regained one of our guns which had been overrun by numbers. The enemy, Miles’s division, reported a loss for the day of 571. The march of our column was continued under the protection of Mahone’s division, with but one slight interruption.

Crook’s division of cavalry forded the river on our left and moved toward our train. Gregg’s brigade, in the lead, was charged by Mumford and Rosser, and Gregg and a bunch of prisoners were captured, on which the rest of the division was withdrawn. Our march was now kept up all night and the next day until sundown. I rode off from the road, after midnight, with my staff and found a fence corner where we could rest awhile without having our horses stolen as we slept, for I had now had but one night’s rest out of six.

After sundown on the 7th, Mahone, still holding the road against the 2d corps under Humphreys, asked a flag of truce to enable him to remove the wounded, left in front of his line when he charged and captured the colors of the 5th N.H. When the reply came, granting the truce for an hour, it brought also a letter from Grant to Lee, as follows:—

“APRIL 7, 1865.

“GENERAL: The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

“U. S. GRANT, Lt.-Gen.”

Lee, at that moment, happened to be near Mahone’s lines, and within an hour the following reply was delivered to Gen. Seth Williams, the bearer:—

“APRIL 7, 1865.

“General: I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

“R. E. LEE, Gen.”

The next day, the 8th, was the first quiet day of our retreat. The 2d corps followed us up closely, but there was no collision. All the rest of the Federal army had taken the more direct road which I had seen on Lee’s map, and was marching to get ahead of us at Appomattox C. H. During the day I rode for a while with Gen. Pendleton, our chief of artillery. Ho told me that some of the leading generals had conferred, and decided that it would be well to represent to Lee that, in their opinion, the cause was now hopeless, in order that he might surrender and allow the odium of making the first proposition to be placed upon them.

But it was thought that Longstreet was the man to make the proposition to Lee. Longstreet had not been consulted, and Pendleton had undertaken to broach the matter to him, and had done so. Longstreet had indignantly rejected the proposition, saying that his duty was to help hold up Lee’s hands, not to beat them down; that his corps could still whip twice its number and as long as that was the case he would never be the one to suggest a surrender.

On this, Pendleton himself had made bold to make the suggestion to Lee. From his report of the conversation, he had met a decided snub, and was plainly embarrassed in telling of it. Lee had answered very coldly, “There are too many men here to talk of laying down their arms without fighting.”

Evidently Lee preferred to himself take the whole responsibility of surrender, as he had always taken that of his battles, whatever their issue, entirely alone.

Some time in the afternoon he received Grant’s reply to his inquiry as to the terms proposed. It was as follows:—

“FARMVILLE, April 8, 1865.

“GENERAL: Your note of last evening in reply to mine of same date, asking the condition on which I will accept the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia is received. In reply I would say that peace being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon, namely, that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified from taking up arms again against the government of the United States until properly exchanged. I will meet you, or will designate officers to meet any officers you may name for the same purpose at any point agreeable to you for the purpose of arranging definitely the terms upon which the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia will be received.

“U. S. GRANT, Lt.-Gen.”

Lee received this late in the afternoon of the 8th. It was answered from the roadside and delivered to Humphreys after sundown for transmission to Grant. Lee had but recently been appointed commander-in-chief of all the Confederate armies, and he now delays the surrender of his own army in order that the negotiation may include that of all the Confederate forces under his command. In accomplishing this he might reasonably hope to secure the best possible terms, as it would bring instant peace everywhere. His letter was as follows:—

“April 8, 1865.

“General: I received at a late hour your note of to-day. In mine of yesterday I did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, but to ask the terms of your proposition. To be frank, I do not think the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this army, but, as the restoration of peace should be the object of all, I desire to know whether your proposals would lead to that end. I cannot therefore meet you with a view to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia, but as far as your proposal may affect the Confederate States’ forces under my command, and tend to the restoration of peace, I should be pleased to meet you at 10A.M. to-morrow on the old stage road to Richmond between the picket-lines of the two armies.

“R. E. LEE, Gen.”

This letter was received by Grant at Curdsville, a roadside village on the road Lee had travelled, about midnight. It was not answered until in the morning, as Grant did not intend to accept Lee’s invitation to meet him at 10 A.M. Grant had doubtless had an early interview in his mind when he sent his second letter, and was probably accompanying the 2d corps, that he might be conveniently near. But he had been recently cautioned from Washington about making or discussing any political terms, and, as Lee’s letter seemed to involve a chance of such discussions, he apparently decided to make the proposed meeting impossible by at once leaving that road and riding across to the road being travelled by Ord and Sheridan.

Before starting, however, he replied to Lee from Curdsville, as follows:—

“APRIL 9, 1865.

“GENERAL: Your note of yesterday is received. I have no Authority to treat on the subject of peace. The meeting proposed for 10 A.M. to-day could lead to no good. I will state, however, General, that 1 am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertains the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed.

“Seriously hoping that all our difficulties may be settled without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself, etc.

“U. S. Grant, Lt.-Gen.”

Meanwhile, during the afternoon, we had approached Appomattox C. H., two miles beyond which was the junction of our road with the one on which Sheridan and Ord were now approaching, and already the advanced guards of the two forces were in collision. Lee arranged during the evening with Gordon and Fitz-Lee, who had the advance, that they should make a vigorous attack at dawn and endeavor to clear the road. This was done, and, in evidence of it, a battery of 12-Pr. Napoleons was presently sent in to me, having been captured by a cavalry charge of Robert’s brigade. Though this evidenced good spirit on the part of our men, our advance made no progress, and the increased fire told of large forces already in our front. Lee was up at an early hour and sent Col. Venable to Gordon to inquire how he progressed. Gordon’s answer was:—

“Tell Gen. Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet’s corps.”

When Lee received this message, he exclaimed:—

“Then there is nothing left me but to go and see Gen. Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

Venable writes:—

“Convulsed with passionate grief, many were the wild words which we spoke as we stood around him. Said one, ‘Oh, General! What will history say of the surrender of the army in the field?’ He replied, ‘Yes, I know they will say hard things of us. They will not understand how we were overwhelmed by numbers. But that is not the question, Colonel. The question is, is it right to surrender this army? If it is right, then I will take all the responsibility.’”

Meanwhile, the march of the army had come to a halt in front, while, for a time, the rear closed slowly up. I had bivouacked near the road, and soon after sunrise I came upon Lee with his staff by the roadside, at the top of a hill. The general called me to him, and taking his seat upon a felled oak, peeled off its bark, and referring to the map we had looked at together on the 7th, he said:1—

“Well, we have come to the Junction, and they seem to be here ahead of us. What have we got to do to-day?”

I had been somewhat prepared by my talk with Pendleton, had formulated a plan of my own, and was glad to have a chance to present it. My command having been north of the James had had no share in the fighting about Petersburg, and but little in the retreat. They had now begun to hear of a surrender, and would hint their sentiments in loud voices when I rode by.

“We don’t want to surrender any ammunition. We’ve been saving ammunition all this war. Hope we were not saving it for a surrender.”

I told the general of this and said that if he saw fit to try and cut our way out, my command would do as well as they had ever done.

He answered:—

“I have left only two divisions, Field’s and Mahone’s, sufficiently organized to be relied upon. All the rest have been broken and routed and can do little good. Those divisions are now scarcely 4000 apiece, and that is far too little to meet the force now in front of us.”

This was just the opportunity wished, and I hastened to lay my plan before him. I said:—

“Then we have only choice of two courses. Either to surrender, or to take to the woods and bushes, with orders, either to rally on Johnston, or perhaps better, on the Governors of the respective States. If we surrender this army, it is the end of the Confederacy. I think our best course would be to order each man to go to the Governor of his own State with his arms.”

“What would you hope to accomplish by that?” said he. “In the first place,” said I, “to stand the chances. If we surrender this army, every other army will have to follow suit. All will go like a row of bricks, and if the rumors of help from France have any foundation, the news of our surrender will put an end to them.

“But the one thing which may be possible in our present situation is to get some sort of terms. None of our armies are likely to be able to get them, and that is why we should try with the different States. Already it has been said that Vance can make terms for N.C., and Jo Brown for Ga. Let the Governor of each State make some sort of a show of force and then surrender on terms which may save us from trials for treason and confiscations.”

As I talked, it all looked to me so reasonable that I hoped he was convinced, for he listened in silence. So I went on more confidently:—

“But, General, apart from all that—if all fails and there is no hope—the men who have fought under you for four years have got the right this morning to ask one favor of you. We know that you do not care for military glory. But we are proud of the record of this army. We want to leave it untarnished to our children. It is a clear record so far and now is about to be closed. A little blood more or less now makes no difference, and we have the right to ask of you to spare us the mortification of having you ask Grant for terms and have him answer that he has no terms to offer. That it is ‘U.S., Unconditional Surrender.’ That was his reply to Buckner at Fort Donelson, and to Pemberton at Vicksburg, and that is what is threatened us. General, spare us the mortification of asking terms and getting that reply.”

He heard it all so quietly, and it was all so true, it seemed to me, and so undeniable, that I felt sure that I had him convinced. His first words were:—

“If I should take your advice, how many men do you suppose would get away?”

“Two-thirds of us,” I answered. “We would be like rabbits and partridges in the bushes, and they could not scatter to follow us.” He said: “I have not over 15,000 muskets left. Two-thirds of them divided among the States, even if all could be collected, would be too small a force to accomplish anything. All could not be collected. Their homes have been overrun, and many would go to look after their families.

“Then, General, you and I as Christian men have no right to consider only how this would affect us. We must consider its effect on the country as a whole. Already it is demoralized by the four years of war. If I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live. They would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy’s cavalry would pursue them and overrun many wide sections they may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.

“And, as for myself, you young fellows might go to bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be, to go to Gen. Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences of my acts.”

He paused for only a moment and then went on.

“But I can tell you one thing for your comfort. Grant will not demand an unconditional surrender. He will give us as good terms as this army has the right to demand, and I am going to meet him in the rear at 10 A.M. and surrender the army on the condition of not fighting again until exchanged.”

I had not a single word to say in reply. He had answered my suggestion from a plane so far above it, that I was ashamed of having made it. With several friends, I had planned to make an escape on seeing a flag of truce, but that idea was at once abandoned by all of them on hearing my report.

At this time the negotiations had been definitely broken off by Lee’s second letter. The meeting which this proposed had been declined by Grant in a letter now on its way to Lee, but not yet received. He had told me Grant’s terms as if he knew them, but later he felt some uneasiness lest Grant might not feel bound by his offer after it had once been declined. Longstreet, in Manassas to Appomattox, mentions his apprehensions on this subject, but states that he, from personal acquaintance with Grant, felt able to assure Lee that there would be no humiliating demands, and the event justified that assurance.

About 8.30 o’clock Lee, in a full suit of new uniform, with sword and sash and an embroidered belt, boots, and gold spurs, rode to the rear, hoping soon to meet Grant and to be able to make the surrender. Instead, he learned of Grant’s change of route and was handed Grant’s letter, dated that morning, and declining the interview. He at once wrote a reply as follows, and asked to have it sent to overtake Grant on his long ride.

“APRIL 9, 1865.

“GENERAL: I received your note of this morning on the picket line whither I had come to meet you, and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

“R. E. LEE, General.”

While this last message was being prepared, a messenger riding like the wind dashed around a curve, and seeing Lee, and having but one arm, with difficulty stopped his horse nearly 100 yards beyond. All recognized the rider, Col. John Haskell of Longstrcet’s artillery, and, as his horse was checked, Lee went to meet him, exclaiming: “What is it? What is it?” and then, without waiting for a reply: “Oh, why did you do it? You have killed your beautiful horse!”1

Haskell explained that Fitz-Lee had sent in a report that he had found a road by which the army could escape, and that Longstreet had ordered him to overtake Lee, before he could send a note to Grant, and to kill his horse to do it. Longstreet, in his book, says that Haskell’s arrival was too late, that the note had gone. But Humphreys’s narrative shows that Col. Whittier, who took the note, witnessed Haskell’s arrival before the note was finished. Lee, however, had not credited the report, and a later messenger soon came to say that the report was a mistake.

When Field’s division had been halted by the flag of truce, Humphreys’s corps was within a half-mile, and under his orders it soon appeared to be making preparation for a further advance. Field, meanwhile, went to intrenching. Grant had instructed Humphreys not to let the correspondence delay his movements.

In Longstreet’s front Gordon had all the morning been engaged with Sheridan, and firing, both of musketry and artillery, was still in progress. Lee had at first neglected to give authority to ask for a truce, but later sent it to Gordon who sent Maj. Sims of Longstreet’s staff to request one. Sims met Custer who had himself conducted to Gordon, and demanded the immediate and unconditional surrender of the army, which Gordon refused. Custer said:—

“Sheridan directs me to say to you, General, if there is any hesitation about your surrender, that he has you surrounded and can annihilate your command in an hour.”

Gordon replied:—

“There is a flag between Lee and Grant for the purpose of surrender, and if Gen. Sheridan decides to continue the fighting in the face of the flag of truce, the responsibility for the bloodshed will be his and not mine.”

On this, Gordon says, Custer rode off with Maj. Hunter of Gordon’s staff, “asking to be guided to Longstreet’s position.” Finding Longstreet, he made the same demand for immediate and unconditional surrender. I have told of this scene elsewhere1 more at length, but did not know until the recent publication of Gordon’s book, that it was Custer’s second attempt that morning to secure the surrender of the army to himself. Longstreet rebuffed him, however, very roughly, far more so than appears in Longstreet’s account of the interview.

Meanwhile, in our rear, more serious trouble threatened. The 2d corps, closely followed by the 6th, began to advance. Lee, who was still awaiting between the lines Grant’s reply to his letter (which had over 15 miles to go, and did not reach Grant until 11. 50 A.M.), sent by his staff-officers two earnest verbal requests to Humphrey snot to press upon him, as negotiations were going on for a surrender. Humphreys, under his orders, felt unable to comply, although the second request was very urgent. He sent word to Lee, who was in full sight on the road, within 100 yards of the head of the 2d corps, that he must withdraw at once.

Lee then withdrew, and the 2d corps continued to advance, and deployed in front of Field’s intrenchments, and the 6th corps also deployed, on the right of the 2d, ready to assault. At the critical moment when this assault was about to begin, it was suspended by the opportune arrival on the ground of Meade. Meade had read Lee’s letter to Grant of that morning, and he took the responsibility of sending Lee a letter granting a truce of one hour, in view of the negotiations for a surrender. This letter was delivered at Field’s lines, and, Humphreys says, was received by Lee between eleven and twelve o’clock. This truce may have been prolonged, for it must have been as late as 1 P.M. before the message sent by Babcock from the front, to be presently told of, could have been started.

Meanwhile, during the morning, and before the first flag of truce was sent, Longstreet had directed me to form a line of battle on which all of our available force could be rallied for a last stand. I got up all the organized infantry and artillery in the column, and took up a fairly good position behind the North Fork of the Appomattox River. To our left the enemy was still extending his lines, and some of my battery commanders were anxious to expend on them some of the ammunition they had hauled so far, for the firing had not yet ceased. But I knew that Lee would not approve an unnecessary shot, and not one was fired from our line.1

When the truce in our rear was for the time arranged, Lee returned to our front and stopped in an apple orchard a hundred yards or so in advance of our line where I had some fence rails piled under a tree to make him a seat.1 Here Longstreet joined him, and they again discussed the chances of Grant’s making some humiliating demands. Humphreys’s refusal to recognize Lee’s presence between the lines as constituting a truce, while awaiting the reply to Lee’s proposal to surrender on Grant’s terms, and the reluctantly allowed single hour of truce as the alternative of instant battle, naturally made them, perhaps, suspicious. Few in either army yet knew of the liberality with which Grant was prepared to treat us. The general temper had been illustrated in the fight at Sailor’s Creek by the Chaffin’s Bluff battalion, under Stiles, who tried to insist upon fighting to the last ditch. Even Lee and Longstreet, under the present circumstances, could not feel confidence in their hope that he might not demand unconditional surrender. So as they sat together under the apple tree awaiting the coming of Grant’s messenger to summon Lee to the conference, silence gradually fell between them. The conversation dropped to broken sentences, and there were occasional long silences between them. The last thing said was by Longstreet to Lee, as Grant’s messenger was seen approaching. It was:—

“General, unless he offers us honorable terms, come back and let us fight it out.”

Grant’s messenger was Col. Babcock of his staff, who had ridden ahead for eight miles with the reply to Lee’s last note. Less formal than the previous correspondence had been, and using for the first time the customary terms of courtesy, it conveyed assurance that no unpleasant surprises were to be expected. It read:—