Chapter 8

Globalizing sanctity

The cult of saints crossed global horizons as part of the spread of Roman Catholicism that accompanied what world historians call the occidental breakout. The breakout began in the late 15th century with the maritime expeditions of Catholic Portugal and Spain. The Portuguese opened up routes, via Africa, to Brazil, and Goa and Calicut on the west coast of India, and beyond to Indonesia, the Spice Islands, China, and Japan. The Spanish colonized South America, parts of southern North America, the Caribbean, and coastal islands off Africa, and the Philippines.

Mission and sainthood

In all these places the cult of saints gained a foothold as part of the religious mission of the Europeans. The Church was relatively muted on the conduct of world mission. Previous Popes had tied its hands by granting the imperial rulers of the Iberian Peninsula full jurisdiction, the patronata (patroado in Portuguese), over ecclesiastical organization abroad.

The mendicant orders were often the earliest to minister to the native populations, but the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) was the nearest the Church came to centrally orchestrated global mission. St Francis Xavier, a founding member of the Jesuits, arrived in Japan in 1549 in the early days of what proved to be an unsuccessful Christian mission there. The civil war in Japan of the second half of the 16th century was won by the Tokugawa dynasty. The new regime embraced a Buddhist political culture, persecuted Jesuits and mendicants at court, and among their local Christian congregations, eradicating the priesthood and driving Christian communities underground.

Jesuit martyrdoms in Japan, the Philippines, and Canada became a powerful recruitment tool for pious young men in Europe. Wall paintings of the martyrs brought inspirational stories of mission into the living space of the Sant’ Andrea al Quirinale noviciate in Rome, while the ambulatory frescoes of Rome’s Santo Stefano Rotondo depicting early church martyrs, and a book containing engraved reproductions of them, through their evocation of the Catholic Church triumphant, fed the spiritual imaginations of young Jesuit missionaries to Germany and beyond. Similar engravings were distributed, according to an annal from the English Jesuit College in Rome, ‘ … even to the Indies, that the infamy of this most disastrous persecution, the frenzied rage of the heretics, the unconquerable firmness of the Catholics, may be known everywhere’.

The Americas

At the far western extreme of the European breakout, the most successful seedbed of sainthood was the Americas. There, the Church received most patronage when it operated as an ideological arm of colonial government, working to pacify and economically exploit the Amerindian natives. By 1620, there were thirty-six bishoprics, two universities, and 400 priories in New Spain. Positions in the Church were drawn from the creoles (American-born Iberians) and the peninsulares (new Iberian arrivals). The Amerindians were excluded from ordained positions in the Church, though they could serve in the liturgy and in tertiary religious institutions.

Colonial sainthood

The European habit of labelling as ‘New’ that part of the world it encountered after Columbus’s famous crossing of the Atlantic in 1492 has privileged colonial perspectives of that historical encounter ever since. It reinforced territorial claims, gave the impression that these worlds were ‘box fresh’, waiting to be possessed, and ignored all that historically preceded the advent of Europeans in the land. The conquistadores treated the Indios harshly. The encomienda system legally enforced a kind of medieval serfdom in which communities were tied to land as units of labour ‘entrusted’ to Spanish soldiers, administrators, and churchmen. Forced labour in the silver mines of Potosí (modern Bolivia) was even worse. Smallpox reduced the immunologically vulnerable population to almost 10 per cent of its original level by 1650. The consolidation of plantation economies fed by slaves abducted from Africa brings more texture to our understanding of the word ‘New’ in this colonial setting.

In these miserable conditions, we might ask why the indigenous people adopted the religion of their Christian oppressors and what part saints played in that process. The brief answers are because there was little else they could do, and that saints were an important channel of communication and authority for natives otherwise excluded from ordination and office. A brief survey of the saints who emerged from these protracted encounters suggests a dynamic situation on the ground in which colonial sainthood took the metropolitan Catholicism of the Tridentine Church and transformed it to suit local conditions. The Americas were inhabited by old civilizations (the Incas and Aztecs), hunter-gatherers, and nomadic warriors, all with their own religious specialists, cultures, and rituals, and, joined by the religions of Africa, they brought their own novelty to an Old World phenomenon.

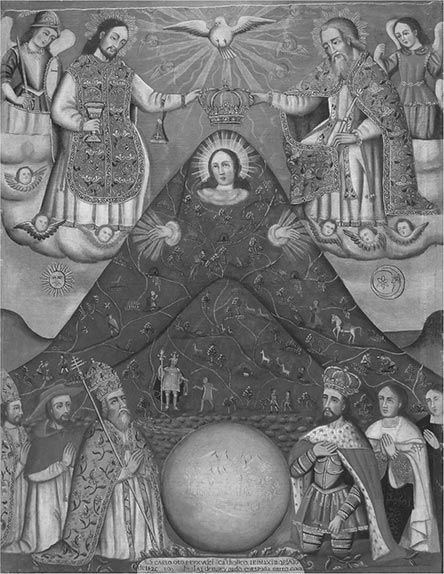

For over a century Potosí was the engine of a new world economy, its chief raw material driving an accelerating carousel of commodities between Europe and silver-hungry China in the Far East. It is perhaps no surprise to note that in such circumstances arose a devotional fondness for the Virgin Mary. A sumptuous 18th-century painting, La Virgen del Cerro Rico (see Figure 9), depicts the Virgin in a dress that is also Cerro Rico, the silver mountain of Potosí. Embroidered on its foothills and ascents are native mineworkers supervised by an Inca ruler. In the foreground of the image are its European patrons, among them Pope Paul II and Emperor Charles V. In this painting the Virgin is a model of syncretic sanctity, replacing Pachamama, the Andean goddess traditionally associated with Mother Nature, as protector and creator of bounty.

9. La Virgen del Cerro Rico, oil on canvas, 18th century, anonymous. Casa Nacional de Moneda, Potosí, Bolivia.

Syncretic sanctity

A fundamental feature of Catholic world mission was syncretism, the mixing of elements of two sets of religious belief and meaning through the adaptation of symbols and practices culturally accommodating to both. In these syncretic conditions, dogma alternated with improvisation, and the simple desire for human association and understanding occasionally registered a foothold on a mental landscape of racial prejudice, and fear borne out of exploitation.

The chief agents and agencies of syncretism on the one hand were those of the mendicant religious orders and the Jesuits, some the product of settler marriages with native families. A remarkable example was the Dominican and early colonial bishop, Bartolomé de Las Casas, whose several writings revealed the degree and character of destruction wrought on indigenous peoples, and who began to articulate a theory of racial equality and native rights in response to it. On the other hand were indigenous converts seeking protection, status, and a voice in the new colonial environment. The aspects of Christian practice that were more accessible and familiar to such groups, especially when they were barred from ordination, were the charismatic leadership of religious men and women, and saintly patronage.

New Spain

In New Spain, the Jesuits and Dominicans learned native languages to aid catechism and confession, and adopted Nahuatl, a lingua franca, to convey doctrine in writing. The indigenous faithful gradually learned Christian doctrine and practice, and were given public roles in ceremonies and festivals that echoed pre-existing traditions of religious observance. When the beatification of Ignatius Loyola was celebrated at the Jesuit headquarters in Cuzco, Peru, in 1610, the figures of eleven Inca monarchs were paraded and their portraits subsequently displayed on the walls of the college.

The 17th-century creole Jesuit Antonio Ruiz de Montoya (d.1652) worked among the Guaraní people of Paraguay. His book, La Conquista Espiritual del Paraguay, gives an account of Jesuit mission to, and settlement of, the native Guaraní people in reducciones, the new settlements in cleared areas of forest. One historian has noted how the Jesuits competed with the local forest shamans for the devotional attentions of the Guaraní. They blessed statues the Guaraní brought them in which were hidden amulets dedicated to San La Muerte, a death figure of local folk religion. But they also tracked down the shrines of forest shamans and had them destroyed. In 1628, Roque González de Santa Cruz, a Jesuit missionary of Spanish noble descent, was killed by a local shaman, Nehcu. He was beatified in 1634 and canonized in Asunción, Paraguay, by Pope John Paul II in 1988.

The most famous example of syncretism in New Spain is the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Tepeyac, Mexico City. Its origins in the first two or three decades of Spanish settlement are obscure, but clearly rose out of an indigenous religious enthusiasm lately acknowledged by the Church. The story surfaces in the mid-17th-century account by a creole priest, Miguel Sánchez, of Juan Diego, a poor Amerindian instructed in 1531 by the Virgin in a vision to build a chapel in her honour in Tepeyac (the cult site of Tonantzin, an Aztec mother god). It took a series of further visions, in one of which his cape became imprinted with the image of the Virgin left by mountain flowers, and a miracle, before Juan Diego could convince his bishop to build a chapel. Women were often conduits and interpreters of native culture in association with male religious authorities. The Americas’ first canonized saint (in 1671) was St Rosa of Lima (d.1617), daughter of a Spanish military family, who died aged 31 after a life of asceticism, penance, and local charity in emulation of the medieval Dominican tertiary, St Catherine of Siena.

New England

North America was colonized by Protestant Europe in the 17th century, in three areas: Chesapeake Bay, in what became Maryland and Virginia; New Amsterdam, later New York; and the Massachusetts Bay Colony of Boston and New England. Those who arrived in New England were Puritans breaking away from the intolerable compromises they associated with Anglicanism. They sought to institute in New England a Church of the godly elect, a community of saints like that of the primitive Pauline church. In the absence of immediate monarchical or ecclesiastical authority, the congregation of saints forged itself from a combination of civic authority and mutual, communal moral scrutiny. The early churches of New England were sectarian; they defined themselves against inferior Christians of universal churches, and, in their efforts to resemble that heavenly community of the righteous predestined, they excluded those whose moral behaviour fell short of what they considered visible sanctity. The temptation of persecution’s former victims to persecute got the better of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Between 1659 and 1661 they executed four Quakers for heresy and witchcraft in a rare sequence of martyrdoms at the hands of saints. Among them was Mary Dyer, executed on Boston Common in June 1660. Her relative anonymity today reflects a Quaker reluctance to celebrate martyrdom, certainly at least in anything other than its broadest spiritual terms as a kind of pain that any of the faithful might endure graciously and without fuss.

New France

The St Lawrence River links the Great Lakes of the American Midwest with the Atlantic Ocean and now defines the border between the USA and Canada. It was named by the 16th-century French explorer Jacques Cartier. The regions it opened up to European colonization (upstate New York, the St Lawrence Valley, and the Finger Lakes) were claimed as New France in the 17th century. The Jesuits undertook missionary work there from 1615 among the peoples of the Iroquois Nation and other Amerindians. The Huron–Iroquois Wars of 1642–9 resulted in the terrible martyrdom of eight Jesuits, captured and tortured to death by native Americans. Isaac Jogues was slain by Mohawks in the mission settlement of Auriesville in 1646. Also among them was St Jean de Brébeuf, responsible for modern Canada’s beloved ‘Huron Carol’, which he wrote in the native writing system he helped to devise. Jean de Brébeuf contributed material to Jesuit Relations, a sequence of multiple-authored ethnographical reports collected over forty years, of Jesuit encounters with native communities. The work contains purported eyewitness accounts of his torture and execution. All eight Jesuits were canonized in 1930.

The story of Jean de Brébeuf and his saintly companions inspired the Frenchman Claude Chauchetière to become a Jesuit in Canada, where, in 1677, he arrived at a mission station called Kahnawake. The same year, Catherine Tekakwitha, a young Mohawk convert to Christianity, and born in the village where Isaac Jogues had been martyred ten years before, arrived at Kahnawake. Her life and death at the mission station two years later inspired miracles, a shrine, and early public veneration only recently acknowledged by Rome, where she was canonized in October 2012. Chauchetière was the chief early advocate of this ‘savage saint’, writing her biography by c.1690. Her asceticism, heroic virginity, and mystical powers, as retold by her Jesuit confessors, made her a fitting successor to her medieval Sienese namesake. But enough contradiction and ‘spin’ emerges from the historical record to suspect that Catherine, and the native female companions with whom she shared the religious life, were not passive imitators of medieval models of sanctity nor easy for the Jesuits to handle, but imaginative spiritual bricoleurs. Their desire to become a religious order led them beyond Jesuit prescription and expectation, and their willingness to repurpose native culture, for example in undergoing extreme suffering as part of their ascetic discipline, startled their Jesuit confessors.

It was customary of Iroquois peoples, by torturing their captives, to offer them a chance through a final show of bravery to nullify the shame of captivity. Self-torture was a practical way of preparing for the possibility of capture, but such violence also had a sacred dimension to it compatible with Catholic ascetic practice. Accounts of Iroquois warriors eating Jesuit hearts imply they shared a degree of admiration for the stoical suffering of their Christian captives. Physical suffering was a meaningful way for Catherine to test her own progress in the faith, by imitating the flagellation, fasting, and sleep deprivation practised by the Ursuline hospital nuns, and improvising native variations on them. Catherine punctured her whole body by rolling around in thorn bushes, exposed herself to extremes of temperature, walking barefoot on the ice, and applying firebrands to the skin between her toes while saying the Ave Maria; she dislocated her shoulders and, when not fasting, mixed ash into her food. It all won her the baffled awe of her Jesuit confessors, schooled in a European assumption of the savage woman as a dumb slave to sexual compulsions.

Africa

The kingdom of Kongo was converted under Portuguese missionary influence by King Afonso I (1509–43). Afonso had defeated his brother after invoking St James ‘Matamoros’ on the battlefield. Kongolese Catholicism endured into the 18th century as a mix of Catholicism and the native folk ritual of kindoki. Because the Kongolese ruling elite impeded European control of its ecclesiastical structures, and Portuguese involvement in the slave trade undermined the moral status of its clergy, the established Kongolese Catholicism was highly Africanized. When the state lapsed into protracted civil war after the 1660s, a peculiarly African form of charismatic Christian leadership provided a focus for peace and unity around the cult of a young Kongolese woman, Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita. Beatriz Kimpa Vita was a nganga, a spirit medium in the kindoki tradition, until 1704, when, inspired by Capuchin missionaries, she announced herself to have died, been resurrected, and possessed by St Anthony of Padua. Beatriz went on to mobilize a popular religious movement, the Antonians, on the strength of a revelation entrusted to her that Jesus, Mary, and St Francis had all been Kongolese.

The Antonians occupied the war-torn capital of São Salvador, before one of the disputing kings in the civil war captured and burned their ‘living dead’ leader for heresy and witchcraft in 1706. Beatriz’s cult has been interpreted by turns as a peace movement, an anti-slavery movement, and an anti-colonial religious movement. It certainly represents another example of Africa’s great religious creativity. Antonianism resurfaced in the North American colonies when, in 1739, Catholic Kongolese slaves broke their chains at Stono Bridge in South Carolina in a bid for liberty in Spanish Florida. Ironically, in Brazil, St Anthony of Padua had already acquired quite a different reputation. He was the recoverer of lost objects, and specifically for mamelucos, or slave-hunters, of runaway slaves. Portuguese colonials also called upon him as a military saint in the blessing of fortresses.

The African noblewoman Walatta Petros (d.1642) is the most historically prominent among a number of Habasa noblewomen of the Täwahedo Christian Church of highland Ethiopia. The depiction of these women in Western accounts, and in Walatta Petros’s case in her own biography written within thirty years of her death, clearly indicates their dogged leadership of native Christian resistance to the proto-colonial mission of Portuguese-backed Jesuits. The centralizing and hierarchical refinements that Roman Catholicism brought to political authority in the region help to explain the protection and endowment it received from early 17th-century Habasa kings. To frustrate this emerging alliance, however, several high-status noblewomen gained a reputation in Portuguese accounts as highly literate, obstinate heretics, annoyingly skilled at public disputation, and at cursing. The Gädla Walatta Petros, or ‘life-struggles of the spiritual daughter of Peter’, preserves an image of its heroine as a model of asceticism, a founder of monasteries, and reformer of religious life, and as a mother figure and intercessor for the native Christian faithful. On one occasion in her biography Walatta Petros is summoned to court to dispute with ‘three renowned European false teachers … about their filthy faith’. Her response is succinctly recorded: ‘she argued with them, defeated them … laughed and made fun of them’.

Modern syncretic sanctity

Other examples of Christian syncretism, among them Candomblé in Brazil, and Santería in the Caribbean, operate beyond official approval and submerge African cosmologies in outwardly Catholic rituals; the identities of the orishas, or deities, of the Yoruba tradition, for example, are blurred into those of familiar Catholic saints. The cult of Santa Muerte, or St Death, has flourished over the last two decades among Mexicans in Central and North America. Devotion to the ‘Bony Lady’ has obscure roots in the colonial period, but the scale of its current resurgence is unprecedented. In association with the Mexican government the Catholic Church has raised concern for the cult’s demonic aspects and stressed its associations with narcotics trafficking and gang culture. Wayside shrines have been bulldozed, and attempts to secure its official recognition by the Church spurned. Still, it exists in a variety of benign everyday settings for its devotees, who light differently coloured candles to secure one form of assistance or another from the saint.