The Making of the Soviet Dacha, 1917–1941

It is a startling fact that dachas, which had enjoyed such a high profile before the Revolution, had by the 1930s gained a secure niche in a new order that existed under very different social and economic conditions and espoused an ideology radically hostile to cultural remnants of the old regime. But is this continuity real or illusory? Can one really see any meaningful connection between the dachas depicted in Chekhov’s stories and those of the Soviet elite in the 1930s? Are not these two sets of phenomena separated by a violent rupture that makes continuity hard to conceptualize in any satisfactory way?

Improbable as it might seem, points of connection can be found. The survival of the dacha calls into question the notion of the Revolution as a clean break in the social and cultural history of the major cities. The dacha is hardly the only thing that survived, of course: ostensibly improbable continuities have been traced in other areas of early Soviet life ever since Nicholas S. Timasheff, in a pioneering work of 1946, coined the term “Great Retreat” for the partial abandonment of radical social policies and values by the elite of the 1930s.1 In the light of the cogent arguments made by Timasheff and others, the dacha might well be seen as just one of several prerevolutionary cultural status symbols that were appropriated by a new Soviet “middle class.”

Even if we find signs of the past in Stalin-era culture, however, we are still left with important questions unanswered. For example: What were the causes of the Great Retreat—social or political expediency, the self-interest of an elite, or some more complex set of historical factors? How did it fit in with other aspects of Soviet life that, far from suggesting a retreat from revolutionary aspirations, remained aggressively radical and transformative? There is a need, in other words, to test the Timasheff paradigm against detailed social history: to show how the interaction of continuity and change took place in practice, how it informed social practice and affected people’s lives.

These tasks can usefully be related to an enduring historical debate that investigates the balance between “traditional” and “modernizing” principles in the working of the emerging Soviet system: the Great Retreat, so one argument runs, took place in a society that was very self-consciously entering a form of modernity, and it is this assertively modern orientation of Soviet society, not its traditional or conservative aspects, that needs to be emphasized.2 Another approach directs attention elsewhere: to the ways in which modernizing structures, policies, and intentions led to “neotraditional” results.3 One example is the Soviet bureaucracy, which, though designed to strengthen the centralized state and inculcate impersonal standardized practice, may actually have forced people into greater reliance on more “traditional” forms of behavior, ranging from unofficial networking to the cultivation of allotments for subsistence.

To seek out traditional and modern elements in Soviet society, then, is a worthwhile project but on its own it is inadequate. The next step is to examine their interaction over time, and we can best do so microcosmically—by fixing our attention on limited objects of study, such as the dacha. As well as bringing us face to face with the charged issue of periodization in Soviet history, the dacha can thus also provide insights into the workings of early Soviet urban society.

Exurbia in Revolution and Civil War

The revolutions of 1917 brought a rapid depopulation of the dacha areas surrounding the major cities. Just as in 1905, when popular unrest in the outlying areas of Moscow and St. Petersburg had scared away some dachniki for years, people were unwilling to expose themselves to the risk of revolutionary violence and in many cases simply left their property behind. Other dachas fell vacant not because they had been abandoned but because their owners had been called away—to the front, to the city, on business, or to relatives in other regions.

Housing in the major cities was liable to be suddenly and violently appropriated by the new regime. In Petrograd, for example, where revolutionary vengefulness was intense, “bourgeois” families had good reason to fear instant eviction from their homes.4 The situation in exurban locations was less clear and more variable. Although in some places privately owned houses were municipalized almost instantly, the authorities had neither the time nor the inclination to take full control of the dacha stock. The action taken in a particular village or settlement depended on the vigilance and activism of the local soviet—and, not least, on the behavior of the local population. Isaiah Berlin (b. 1909) and his mother escaped “the increasing tension and violence in the city” by moving to Staraia Russa for the summer of 1917. And, at least in the eyes of a young boy, life proceeded much as normal: “There were fancy-dress parties, tombolas, and afternoons in the park listening to an Italian orchestra playing at a bandstand.” The Berlins spent the next two summers in Pavlovsk, though here the Revolution did catch up with them, as they were subjected to a humiliating search by the Cheka in 1919.5

In general, dachniki seem to have been considerably less vulnerable than estate owners to revolutionary violence: many of them rented their houses, and even those who were owners of private property could not be seen by peasants as egregiously laying claim to large tracts of land they did not use or need. A case in point was Iurii Vladimirovich Got’e, professor of history and associate director of the Rumiantsev Museum in Moscow, who by September 1918 had resigned himself to losing the modest estate in Tver’ guberniia where he and his family had passed their summers before the Revolution. Instead, for the following few years Got’e spent time in various villages and dacha locations in the Moscow region; most often he sought refuge in Pestovo (forty kilometers north of Moscow), a settlement that during the Civil War was reached by a twelve-verst trek from the nearest railway station. Pestovo had few comforts but offered compensating advantages—it offered a more reliable supply of basic foodstuffs than did the city, and it was largely ignored by the Soviet authorities; by engaging in hard physical activities, moreover, Got’e achieved brief periods of oblivion from the underlying despair he felt at Russia’s catastrophic social and political situation.6

The dacha zones most at risk were those that had been all but swallowed up by the city. In Moscow’s Sokol’niki, any dachas left unattended were liable to be looted, and wooden constructions were sometimes completely dismantled for firewood.7 In Petrograd, one of the first victims of the breakdown of political authority after the February Revolution was the Durnovo dacha on the Neva, seized by anarchists and converted into a “house of rest” for workers. After a lengthy standoff between the anarchists and the Ministry of Justice, the unlawful occupants were evicted by force. But to keep the dacha in private ownership was still unrealistic; even Durnovo’s own staff, on being informed by the anarchists that the dacha was now the “property of the people,” had readily believed this to be the case. In September 1917, Durnovo offered to hand over the dacha as a hospital for tuberculosis patients.8

The Durnovo dacha was a very public and obvious target in view of its central location (by the early twentieth century it was a dacha in name only) and of the fact that P. P. Durnovo had a lengthy record of state service (he had been governor general of Moscow during the 1905 Revolution). Dachas farther from the public eye, however, might also fall victim to revolutionary violence. Aleksandr Blok was one dismayed observer of the devastation of resorts outside Petrograd that had been among his favorite haunts before the Revolution.9 The damage inflicted by looters would often stretch to several thousand rubles’ worth in a single property as houses were laid waste, their fittings stolen, and their interiors vandalized.10

Many dacha owners had already fled, but not everyone was so lucky: some were forced to look on as their property was raided or requisitioned. A woman named Efremova, resident at a dacha in the Moscow region, had in the summer of 1919 been away in the town of Kolomna, where her husband, employed in the financial department of the local soviet, had just died of typhus. On her return, she discovered that neighbors had lured her infirm mother over to their house by promising her regular meals and had taken the opportunity to steal numerous pieces of furniture and other household items. They had plundered property not only from the living quarters but also from the two outbuildings, the keys to which they had confiscated. And they had let out one of the buildings, taking all the rent money for themselves.

Efremova was a typical minor dacha owner of the period. She, her husband, and her father-in-law had bought a plot of 1,209 square sazhens in 1911 and on this land had built three dachas (only one of which was equipped for year-round habitation) with the aim, in Efremova’s words, of “securing the old age” of their parents (in all probability, she intended to rent out the two surplus houses each summer for a modest unearned income). Efremova’s father-in-law, who worked as a typesetter in Moscow, had died in 1915, and since then she and her husband had lived at their dacha continuously.11 People such as the Efremovs, although two of the three “dachas” on their plot were little more than outbuildings, were soon to be classified as multiple property owners and the surplus housing made subject to appropriation by the municipal authorities.

During the Civil War and the first half of the 1920s a huge free-for-all took place in areas lying just outside the city limits. Peasants and other locals were able to occupy houses that had been left vacant. Owners occasionally wrote anxiously to the authorities asking for a protection order on their property, but in most cases were powerless to do anything. The scholar, critic, and children’s writer Kornei Chukovskii was one such victim of theft. When he returned to his dacha in Kuokkala (now on the other side of the Soviet-Finnish border) in January 1925 after an absence of several years, Chukovskii found that his furniture and a large part of his library had been sold by an unscrupulous acquaintance whom he had unsuspectingly allowed to sit out the Civil War there.12 In 1923 the people’s courts were still being swamped with appeals concerning what was often euphemistically called the “unauthorized seizure of property” in exurban locations; it was decided that such cases should have top priority, as any delay meant that the dacha season might come to an end before a verdict was passed.13

Burglaries and acts of random violence against property were, however, by no means the only concern of dacha owners. They also had the new regime and its representatives to reckon with. Municipalization of the housing stock began immediately in Moscow and Petrograd, in adjacent towns, and in high-profile dacha locations with a large number of wealthy householders. In Moscow, all such areas located within the railway ring (Petrovskii Park, Petrovsko-Razumovskoe, Ostankino, Sokol’niki, Serebrianyi Bor, and a few others) were subject to automatic municipalization in 1919.14 A total of 543 country palaces and dachas were used as vacation resorts for workers between 1918 and 1924.15Thirteen dachas on Petrograd’s Kamennyi Island, formerly reserved for high-ranking state personnel, were turned over to a children’s labor colony (named after the first minister of enlightenment, A. V. Lunacharskii) at the beginning of 1919. One dacha owner, Klara Eduardovna Shvarts, was informed abruptly (in person) on 26 December 1918 that her house and its contents were to be appropriated by the Commissariat of Education. This decision was carried out unceremoniously: the house was broken into continuously, and furniture and other items were removed without written authorization.16 The vulnerability felt by prerevolutionary property owners was captured by Got’e in a diary entry of 3 May 1918: “A strange feeling. It is as if everything were as before, but the fact is that the gorillas can come and drive out the legal owners on ‘legal’ grounds.”17

The dacha’s vulnerability to the depredations of the new regime was exacerbated by its suspect ideological standing. Many representatives of Soviet power in the early 1920s considered summer houses to be among the least acceptable manifestations of private property. In 1924, for example, Foreign Minister Boris Chicherin and the head of state, Mikhail Kalinin, had to enter into correspondence with the Leningrad regional executive committee to force this organization to assist Soviet citizens who were reasserting their rights to dachas that were now on the other side of the Finnish border. The committee had refused to support the establishment of a “Society of Dacha Owners in Finland,” claiming that the existing provisions in the Civil Code were quite sufficient and that to encourage such an organization would contradict the “rigorously implemented” policy of municipalizing privately owned houses in Leningrad.18

Policies on dacha ownership during the Civil War were correspondingly severe. A three-month absence was sufficient for a dacha to be classified as ownerless, and failure to register one’s property was also grounds for confiscation. Owners of more than one dacha in a single settlement would typically be left with only one house. Yet evictions by local soviets in dacha areas tended to have only a shaky legal foundation. Strictly speaking, the early Soviet decree on the abolition of private property related only to cities, not to settlements; here, as later in the Soviet period, exurban locations represented an area of uncertainty for Soviet legal procedure.19 In any case, the law, such as it was, seems to have been only haphazardly interpreted and implemented in the early 1920s; influential contacts were the most reliable guarantee of preserving property, though determination and sheer good luck also helped.20

As the new regime sought to extend its control over the capitals and their outlying areas, the newly formed basic territorial units of Soviet power—the district executive committees, or raiispolkoms—were entrusted with supervising the dacha stock. The Primorsko-Sestroretskii raiispolkom, for example—based in one of the most popular St. Petersburg dacha locations of the years before 1917—was kept frantically busy in 1919 and 1920 as it tried to keep some measure of control over the properties that had suddenly fallen under its jurisdiction. In February 1920 its department of local services (Otdel mestnogo khoziaistva, or OMKh) was warned by the regional authorities that it should stop handing out furniture and other household goods to private citizens until it had carried out an inventory of all abandoned and requisitioned property. Even so, the local ispolkom continued to be inundated with requests from individuals for household items, articles of furniture, and entire houses. The range of confiscated items was considerable, from bed linen to clothes brushes, from pots and pans to wallpaper.21

In the early 1920s the pressure on housing was enormous as people flocked to the major cities. As a result, the prerevolutionary dacha stock had been almost entirely redistributed by 1922. In September of that year, the department of local services in Petrograd uezd wrote to the Pargolovo ispolkom inquiring about dachas that could be made available for rest homes, sanatoria, children’s summer camps, and summer vacation homes for people working in regional state institutions. The answer was that all dachas suitable for these uses had already been allocated to new owners and tenants; none had been, or would be, handed out to organizations.22

An impulse to impose some measure of order on the chaotic dacha stock had been provided by a Soviet government decree of 24 May 1922 that called on ispolkoms to compile within two months a precise list of all municipalized dachas (that is, all dachas that were under the control of the soviets). This decree did not signal the start of dacha municipalization (which, as we have seen, was under way in some locations as early as 1918); rather it launched a period of stocktaking.23 During the Civil War, houses had often been municipalized on local initiative, not according to any coherent overall policy; the absence of such a policy had also permitted many dachas ripe for municipalization to stay in private hands. In the way of Soviet decrees, the 1922 decree was promptly translated into an NKVD instruktsiia (that is, a set of guidelines as to how the decree was to be implemented in practice). The latter document called for restraint in redistribution of dacha properties: given the huge demand, only “well-founded applications” should be given consideration; and the transfer of whole dacha settlements to a single institution was strictly forbidden. The communal dacha stock was to be made up, first, of dachas whose owners were absent; second, of “lordly” (barskie) dachas (defined as dachas with at least one of the following attributes: running water, bathroom, electricity, heating; outbuildings; extensive gardens and parks; and fancy fittings); and third, of dachas whose owners had other such property in the same area (in such cases, the owners were to be left with one dacha only). The NKVD suggested a further criterion for those areas (and we must assume they were the majority) where the dacha pool obtained by the above methods was insufficient: on plots where there were several residential buildings, the owners were to be left with one building only.24

In June 1923 the Communal Department of the Moscow uezd soviet reported on its implementation of the municipalization policy.25 It estimated that “up to 35 percent” of all dachas in its territory had now been municipalized. A breakdown by district revealed that the traditionally “bourgeois” settlements located on the Kazan’ and Northern (Iaroslavl’) railway lines had borne the brunt of reappropriation. In all, well over 5,000 dachas had been municipalized: nearly half (49.2 percent) of them had been deemed “unfit” (beskhoziaistvennye); 46.6 percent had been appropriated on the grounds that 125 their owners had other dachas; and 4.1 percent were classified as “lordly” (though it may safely be assumed that many of the “unfit” dachas would have fallen into this category had their owners stuck around to find out).

In order to avoid municipalization, dacha owners had to register their property with the local soviet. By the time of the report, 5,001 private dachas had been registered and a further 2,918 applications were being considered. The understaffed department was struggling to keep pace, especially as applications required proper investigation (apparently many families registered several dachas in the names of various members).

What, though, did the Moscow regional administration do with the 6,000 dachas that were under its control as of summer 1923? The first task it defined was to “review the social composition of those renting municipalized dachas and to take them away from nonlaboring elements [netrudovye elementy] if their number exceeds the regulation maximum.” Municipalized dachas, in other words, were to be subjected to the dreaded “compression” (uplotnenie). No less than 90 percent of the communal dacha stock was to be allocated to the “laboring masses” and to institutions. Rents were set prohibitively high for those outside legitimate employment: from 1 October 1922 to 1 May 1923, nonlaboring elements occupied 75 municipalized dachas and paid 119,341 rubles in rent; workers and employees (sluzhashchie) were allocated 2,223 dachas and charged only 37,516 for the privilege.

Yet the same report contains ample evidence that there were ways around these punitive policies. For one thing, employees generally outnumbered workers, especially in dachas that were rented out to institutions. The category of sluzhashchie was elastic enough to include almost anyone in a nonmanual occupation. The Communal Department clearly distrusted certain tenant organizations, which it suspected were doing little to institute the desired affirmative action policy. In some cases, it was alleged, they simply reinstated the former owners. Such abuses were especially galling given the continuing shortage of accommodations for institutions: in summer 1923 more than 600 institutional applications for dacha space had not been satisfied. Above all, however, dacha owners were putting up resistance to the expropriation of their property. As the report concluded: “In effect a civil war is being played out around the municipalization and demunicipalization of dachas.”26

NEP and Its Liquidation

In due course, however, this civil war showed signs of abating. Citizens were able to appeal for the reregistration of a property in their name as legal regulations and bureaucratic procedures became slightly more stable. Norms for property registration were not so restrictive as they became later in the Soviet period: plots might vary wildly in size, from under 1,000 square meters to over 10,000; in general, however, the area was in the range of 1,500–2,000.27 The demunicipalization policy introduced in 1921 for housing in general began to increase the opportunities for dacha ownership. Glosses on demunicipalization emphasized that its main purpose was to ensure that the housing stock was better maintained. To this end, the criteria for dacha municipalization were to be interpreted more loosely: the mere fact of a Dutch stove was no longer grounds for removing a dacha from private possession. Rather, only “a combination of comfortable appliances and conveniences” gave local authorities the right to put a dacha in the “lordly” category.28

Despite the draconian policies of the preceding period, housing legislation of the 1920s seems laissez-faire compared to that of much of the later Soviet era. The desperately underresourced Soviet state was willing to sanction various kinds of local and private initiative in order to reduce the burden on the center. Until the first five-year plan, nationalized housing played a relatively insignificant role: in 1926, local soviets controlled nearly 60 percent of the overall state sector, and this state sector itself accounted for only around 20 percent of total housing.29 Private and cooperative building were encouraged as a temporary solution to the housing crisis.

But this overview of NEP housing policy is misleading, for two main reasons. First, cooperative housing—which, in the major cities especially, tended to predominate—was by no means independent of Party and state authorities (as the sudden elimination of most urban housing cooperatives in 1937 would subsequently demonstrate). Second, there was great variation from one city to another. The housing crisis was always particularly acute in the major urban centers, and demunicipalization was extremely uncommon there. It was by and large only in provincial towns that urban single-family houses remained in private possession.30

Dachas had an intermediate status. In many ways they were analogous to single-family dwellings in small towns or villages, but they also fell within the catchment area of the major cities where housing policy was most interventionist. In Moscow and Leningrad especially, municipal authorities strove increasingly to establish administrative control not only over the urban housing stock but also over the traditional administrative blind spot of suburban settlements. By 1929, the “trust” now responsible for municipal dacha administration in the Moscow region had taken over 3,100 dachas in around forty settlements.31 In Leningrad, similarly, a separate “communal trust” was formed to supervise and administer the dacha sector. As of July 1926 it reckoned to have control over more than 3,500 dachas.

The intention was to use these new administrative structures to push through centrally directed measures more effectively. By the beginning of 1926, the Moscow soviet had formulated a set of rules for the drawing up of contracts and the renting out of municipalized dachas to institutions and individuals. The rent varied according to the occupation of the tenants: for people working in state, Party, trade union, and cooperative organizations the annual payment was to fall between 5 and 10 percent of the cost of the dacha; factory and office workers and artisans were to pay 3–10 percent; but the “nonlaboring element” was expected to pay not less than 15 percent.32

These new regulations were, however, at best only partially successful in putting dacha ownership and rental on a sound legal footing. Dacha municipalization was never conducted with the thoroughness suggested by policy statements on the subject. There were three main reasons for this failure. First, the huge housing crisis, which, once the Civil War had ended, turned former dacha areas around Moscow and St. Petersburg into shanty settlements inhabited by daily commuters (and so a house, even if classified as a dacha, was likely to be appropriated for year-round habitation). Second, the weakness and disorganization of the local authorities, which often were not able to keep pace with new instructions from the center. Third, the openness of the instructions to variable interpretation (a “lordly” dacha, for example, was very much in the eye of the beholder, and a timely and well-directed bribe would presumably have swayed the judgment of many inspectors from the local housing department).

In the 1920s, Muscovites were so desperate for living space that they were not put off by the disastrous state of most suburban housing. The municipalized stock in 1923 contained 725 dachas (12.8 percent) that were “dilapidated,” 1,771 (31.1 percent) that were “semidilapidated,” and 2,531 (31.1 percent) that required “minor repairs.”33 Yet reports suggest that dachas were almost never left vacant; a very high proportion, moreover, were occupied by commuting year-round residents. As one journalist reported of a village outside Moscow: “Most of the dachniki here are dachniki against their will, they live here all year round because it’s closer to the city where they can’t find an apartment.”34 Special concessions were made to encourage residents to rebuild the housing stock: if a dacha required “major repairs,” tenants were exempted from rent for the first five years they lived there.35 The regional and local authorities received numerous requests for permission to demolish existing buildings and start afresh. Given the acute shortage of housing in the postrevolutionary era, it is little wonder that many people tried to take over or build themselves houses outside the city. The building control committee (Upravlenie stroitel’nogo kontrolia, or USK) of each okrug tried to keep up with this wave of individual construction. Many people, having obtained a plot of land, went ahead and built with or without the necessary permission; others turned former dachas into houses for year-round habitation by installing a heating system; still others converted outbuildings into dachas or shacks for permanent habitation.36 The result of these make-do solutions was a spread of shanty settlements with very low standards of maintenance. One observant British visitor recalled coming across “what appeared from the outside to be a ten-roomed villa or datcha of wood” on a trip into Leningrad’s northern dacha zone in 1937. This house, despite its impressive scale, “was surrounded by a potato-patch and looked so neglected that I thought it must be empty, but I was assured that anything from fifty to eighty people slept there.”37

It is little wonder, then, that the dacha trusts had enormous difficulty persuading local ispolkoms to admit to free dacha space. When the Leningrad okrug administration tried to gauge the extent of the dacha stock in the summer of 1927, very few local ispolkoms volunteered information, mainly because most former dachas had been converted to year-round residences. The one that did provide dacha statistics was the Rozhdestveno volost (taking in Siverskaia and several other settlements to the southwest of Leningrad), which gave a total of over 500 municipalized dachas spread over thirteen settlements. Of these, 152 were being rented out to individuals, 110 were being used by the local ispolkom, 197 were controlled by the education sector, and the rest were empty or unfit for habitation.38

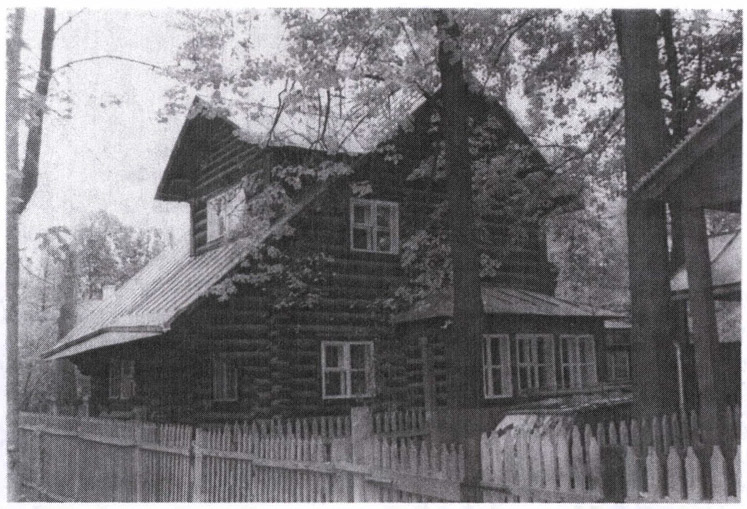

Given that available dacha space was so scarce, the trusts had almost no accommodations to offer the many applicants for a rented summer house. On their own, they had no way of alleviating the shortage, and so more publicity was given to alternative approaches. Some land was offered to individual dacha builders on long-term leases.39 A more striking new development was the coverage given to the cooperative movement. House-building cooperatives had been sanctioned from the beginning of NEP as a means of making good the inadequacies of municipal housing provision. The one-family house of one or two stories was regularly proposed as a solution to the problems facing Soviet urban planning; the prerevolutionary vogue for Ebenezer Howard’s garden cities had not yet run its course.40 The showcase development of this kind was the Sokol settlement in the suburbs of Moscow, where construction began in 1923. This settlement consisted mainly of one-family houses of varied design: from the pseudo-Karelian log house to wood-paneled and even brick houses. The design of the houses emphasized their individual character, while the layout of the settlement—with its small tree-lined streets, some of them curving to form an arc—contrasted with the rectilinear, aggressively modernizing patterns of much early Soviet urban planning.41

A house at Sokol

The houses at Sokol were not dachas but were designed for permanent residence. In the mid-1920s, however, the idea of dacha cooperatives received fresh encouragement, the idea being that they would generate the resources to restore dilapidated dacha stock and to build new settlements.42 Cooperative building projects were further supported by the publication of standard designs for prefabricated dachas that could be assembled in a day without knocking in a single nail and with the help of just a few casual workers.43

Dacha cooperatives established in the second half of the 1920s were suitably modest in their objectives. Most houses built under their auspices were small and made of plywood. Even so, the practical difficulties proved to be immense. Cooperatives required considerable startup capital at a time when bank loans and other kinds of institutional funding were not easy to come by, and individual members did not generally have the personal means to make up the shortfall.44 At the start of the next decade construction projects became more ambitious. In 1932, cooperatives were entrusted with building 1,300 new dachas in the Moscow region (each to a standard design with two apartments, each of three rooms). But here too the press reported severe practical difficulties in obtaining the necessary credits and in coordinating the activities of the cooperative’s various branches.45In due course, attempts would be made to resolve these problems by tying the activities of a cooperative ever more closely to its sponsor organization; as we shall see, the “departmental” principle in dacha management triumphed comprehensively in 1937, when the cooperative movement was dealt a severe blow. Despite the negative press coverage, however, it seems that cooperatives functioned as efficiently as could reasonably have been expected, given the bottlenecked state of the Soviet economy. They also had a deserved reputation for apportioning space more liberally than did municipal settlements. In 1928–29 a dacha cooperative in the Leningrad area, for example, built new settlements at Toksovo and Tarkhovka. By later Soviet standards, these dachas stood on extremely spacious plots. The Toksovo settlement had forty-two plots that averaged 250 square meters, and the proportion of area given up to roads was unusually high; typically, only three or four plots stood in a row.46

But most Muscovites and Leningraders looking for a dacha in the 1920s did not have access to the municipalized stock and were not able to join a cooperative. Instead, they rented rooms or a whole dacha from locals. In April 1926, a representative of the Moscow dacha trust publicly admitted that his organization could not realistically compete with the private dacha market.47 A guidebook to the environs of Moscow, published in 1928, estimates a total of around 300 settlements populated in summer by vacationing Muscovites (these included both dacha settlements proper and peasant villages where houses were rented to city dwellers).48 Dachas were differentiated according to location and amenities. Prices could range from a few dozen rubles for the summer to around 300.49The dacha’s social constituency was by and large urban, educated people for whom the annual migration into the countryside was both a deeply ingrained habit and a cheap and relatively well provisioned alternative to maintaining an urban apartment through the summer months. Memoir accounts suggest that members of the intelligentsia perceived the dacha as a haven for prerevolutionary traditions, a place where they could take their family (and in many cases servants too) and reestablish domestic patterns that were under severe threat in the early Soviet city.50 Even so, there was no concealing the fact that most people’s exurban living conditions had taken a substantial turn for the worse. One memoirist, born in 1915 into a noble family resident in Petrograd, recalled being taken to the dacha each year in the 1920s. In 1927, for example, his mother and aunt rented two rooms in the village of Gorelovo in a “large izba” where everyone slept on hay mattresses; Gorelovo was known at the time to be one of the cheapest dacha locations and was renowned for the quality of its potatoes (a detail that conveys the low expectations of 1920s dachniki).51

Newspapers of the period show the dacha concept being employed in broad and variegated ways. In advertisements of the 1920s and 1930s, the word “dacha” very often expands to mean, approximately, “any single-occupancy house out of town but not in the country.”52 As one would expect for a period of unceasing housing shortage, there were frequent references to “winter dachas” (that is, houses for year-round habitation). Dachas’ size and level of comfort varied enormously, from a dozen rooms to two or three, from full heating, electricity, and running water to zero amenities. Location was another significant variable: for the most part advertisements concentrated on places familiar to the prerevolutionary dachnik, yet other locations were several hours’ journey away. Boris Pasternak, for example, spent the summer of 1930 with his wife at a winterized dacha “of a substantial size” near Kiev.53 The wife of the prominent Soviet writer Vsevolod Ivanov recalled frantically consulting the advertisements in Vecherniaia Moskva in 1929 when she was searching for summer accommodations for herself and her children; in the end she had to settle for a modest izba-style dwelling.54

For certain categories of the population such assiduity was not required. The more comfortable dachas in prime locations in the Moscow and Leningrad regions were soon made available to the families of highly placed Party workers. Dachas in Serebrianyi Bor were seized immediately and the first rest home (dom otdykha) there was set up in August 1921 by decree of Lenin. By 1924 this location contained three children’s homes and one sanatorium, and also accommodated 648 permanent residents in ninety-one buildings. During the 1920s and 1930s many Old Bolsheviks and other prominent figures spent their summers there.55 A dacha settlement named after Mikhail Kalinin was set up by taking over wealthy dachas on the Moscow-Kazan’ railway line; the dacha complex comprised twenty-four houses, many of them spacious prerevolutionary bourgeois residences with parquet floors and charmingly colored Dutch stoves.56 In January 1928 the secretary of the Society of Old Bolsheviks (OSB) wrote to the Central Communal Bank asking for credits toward the construction of twenty two-story dachas, each with accommodations for four families, in Serebrianyi Bor or Kratovo. The letter of application mentioned that some dachas were already in use by the society, but that they were limited to a “select” few. After the bank expressed reluctance to oblige, maintaining that its credit limit for the year had been exhausted and authorization was required to eat into its reserves, a further appeal was made, directly to the Soviet government, and treated more favorably. The main settlement run by the OSB became the one at Kratovo, where the prerevolutionary dacha stock was substantially taken over by the new regime.57

Other favored citizens might spend their vacations in attractive resorts that did not have an exclusively organizational profile. Elena Bonner (b. 1923), daughter of an Old Bolshevik summoned in 1926 to Leningrad after a period of exile in Chita, recalled a carefree summer in Sestroretsk in 1928. Here she was left with her brother and their grandmother and nanny; their parents spent their vacation at a southern resort and made only brief appearances. Life was comfortable and untroubled. The children were indulged with ice cream sandwiches and frequently taken on outings and picnics; the local station had a restaurant with live music and even a kursaal; and the dacha itself was in a wonderfully unspoiled location—in pine forest, not fenced in on any side.58

Yet even for Party families dacha life was not always so idyllic. The following year Bonner was again sent to Sestroretsk for the summer, but this time the dacha fitted a very different model: not unblemished wooded expanses but cramped suburbia. The family did not even have use of the vegetable garden to the rear of the house, and the restaurant had closed down. The year after that (1930) conditions became still less comfortable: Bonner spent the summer in what was effectively a “dacha commune”—a large two-story house, reserved for Party workers occupying “positions of responsibility,” which accommodated three or four families on each floor. Each family had a room of its own (sometimes two). Again her parents were absent for practically the whole summer.59

The leading Bolsheviks’ personal willingness to enjoy “bourgeois” leisure facilities was not, of course, reflected in publicly expressed attitudes toward the dacha. Newspaper reports of the late 1920s concentrated on the outrageous prices asked for summer rental of even a tiny izba. As early as February, people were looking for somewhere to spend the summer months, but most of them were disappointed: dachas at affordable rents were simply not available. The beneficiaries of this situation were, predictably, alleged to be the nepmen, the nouveaux riches of the 1920s: “Only the wives of nepmen in their sealskin and astrakhan coats go around with radiant smiles on their faces. The best dachas in the thousand [rubles] bracket are theirs.”60 As the summer season approached, however, landlords began to lose their nerve if their property had still not been booked, and it was possible to snap up a dacha for less than half the original asking price. Potential tenants still had to be firm in their dealings with the “dacha brokers” who hung around all suburban stations: “they hike up the prices dreadfully, so you simply have to bargain with them. So for a small three-room house with the inevitable veranda they’ll first name you a price of 60 tenners (so as not to scare off the clientele with figures in the hundreds, everything comes in tenners), then they reduce it to 50, and in the end they come down to 400 rubles.”61

The existence of a dacha market was tolerated for most of the 1920s, but it was still treated with deep suspicion. The authorities were especially keen to follow up accusations of profiteering on the dacha market. In 1927 the engineer for Luga okrug (in the Leningrad region) wrote to the presidium of the Luga city soviet to report on alleged serial “speculation”: a current applicant for a building plot by the name of Semenov-Pushkin had several times in recent years registered himself as the owner of empty plots or semidilapidated dachas, only to sell his right to build (pravo zastroiki) without even starting (re)construction work.62 Dachas were further tainted by their association with corrupt practices: in a decade of desperate shortage, it was commonly alleged that the only way to obtain decent summer accommodations, if one was not a bourgeois, was to abuse one’s official position.63

To remark on the unwholesomeness of the dacha became a commonplace of the time. A detailed guidebook of 1926 treated with frank approval any dacha settlement located in the vicinity of an industrial enterprise, but was unremittingly scornful of locations that had apparently preserved their “traditional” clientele and way of life. The following account of a settlement on the Kazan’ railway line was clearly based on prerevolutionary stereotypes (with, to be sure, a generous admixture of anti-NEP ideology):

The train pulls into a noisy, bustling platform—it’s Malakhovka. Various people clamber out of the carriages: “dacha husbands” loaded up with more packages than they can carry; “ladies” with dazzling toilettes; flighty Soviet dames with square “valises” and people in “positions of responsibility” with respectable briefcases that are probably full of old newspapers and journals. . . .

Visitors from Moscow stretch out in a long line along the streets of Malakhovka living in luxurious dachas that are for the most part occupied by moneyed Moscow—by the nepmen.64

The general distaste for the dacha on ideological grounds was mirrored by the attitudes of the artistic and literary avant-garde, for whom the dacha was synonymous with the social and cultural arrière. Note, for example, the metaphors chosen by Sergei Tret’iakov, a prominent figure in the revolutionary arts organization LEF, in this 1923 rallying cry:

[Representatives of the Party] always remember that they are in the trenches and that the enemy’s muzzles are in front of them. Even when they grow potatoes around this trench and stretch out their cots beneath the ramparts, they never allow themselves the illusion that the trench is not a trench but a dacha . . . or that their enemies are simply the neighbors in the dacha next door.65

A journalistic piece of 1922 by Isaac Babel’ describing the conversion of a dacha settlement in Georgia into a resort for working people mixes class hatred with a distaste for everyday life and material comfort typical of Russian modernism: “You petty bourgeois who built yourselves these ‘dachlets,’ who are mediocre and useless as a tradesman’s paunch, if only you saw how we are enjoying our rest here. . . . If only you saw how faces chewed up by the steel jaws of machinery are being refreshed.”66

This unease in publicly expressed attitudes toward the dacha was exacerbated by the uncertain legal status of ownership. Land disputes were rife in former dacha areas in the 1920s. The review of dacha municipalization after the decree of May 1922 had, it turned out, been far from comprehensive, rigorous, and consistent. On inspection (for example, after the death of the owner), a house might turn out to be on neither the municipal nor the nonmunicipal list, which left the local ispolkom unsure how to act. Neighbors might appeal to the local authorities for land bordering their plots. And, especially toward the end of the decade, people’s property rights might be undermined by investigation of their social origins. In 1928, for example, the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate (Rabkrin) insisted that a local ispolkom investigate the social origins of the family of a former “hereditary honored citizen” (that is, a former merchant) and then dispossess them. The property in question, a spacious two-story “lordly” dacha (total area: 233 square meters), had anomalously not been municipalized in 1922. The ispolkom concluded after its investigation that the house should indeed have been municipalized, but that it was now impossible to change the situation because the latest government circular forbade any further action of this kind.67 Many local soviets did not have such scruples, inspecting dachas that earlier slipped through the net of municipalization for signs of “lordliness.”68

Official controls on exurban communities may have been relaxed somewhat in the mid-1920s, but they were reapplied with greater zeal and violence in 1928 and (especially) 1929, when a crackdown on unregistered and misregistered dacha owners formed part of the campaign against “former people” (that is, people of “bourgeois” social origins). Demuncipalization was in many cases reversed without due legal process; registration of private property was canceled on the grounds that administrative errors had occurred.

Not that administrative errors were too hard to find, given the haziness of legal arrangements in the 1920s. Take the following case cited as exemplary in a guide to dacha legislation published in 1935. In 1923, in the settlement Novogireevo (Moscow region), a dacha belonging to one Shchedrin was classified by representatives of the NKVD as being of the “lordly” type and hence municipalized; but Shchedrin had sold it by private agreement to a woman named Ivanova, who in 1922 had gone to court to have herself recognized as the de facto owner. Armed with this judgment, she was then able (in 1923) to register the property in her name. In 1927 she sold it to a new owner, Dobrov. In 1931, in the course of verifying property registration, the local ispolkom uncovered these legal irregularities (that is, the fact that a building originally municipalized was now registered as someone’s private property) and went to court to have Dobrov evicted. The court concluded that Dobrov should indeed be forced to vacate the property, but only after he and his family had been allocated equivalent living space elsewhere.69

So the municipalization decree continued to cause dacha folk enormous trouble even several years after it had supposedly been implemented—but it might also be ignored or manipulated to their advantage until the housing authorities decided to examine the situation more closely. Legal processes, it seems, tended to reflect the specific relationship between individual dacha residents and the representatives of state or municipal power whom they encountered. The class warfare of the late 1920s, however, tipped the balance of power comprehensively in favor of the local ispolkoms and against dachniki. The brutal design of this campaign is clear from an NKVD circular of 1930 that explicitly extended the war against “former people” to dacha locations. The earlier municipalization measures were deemed to have been insufficiently thorough; now the aim was to check the whole of the private dacha stock and to eliminate “profiteering.” Absolutely no more demunicipalization was to be permitted. Even before this, however, the regional department of local services had instructed the dacha trust to check the social composition of tenants throughout the uezd, paying particular attention to “locations that formerly served as vacation places for the bourgeoisie and now for nepmen and people of free professions.”70

The hard-line policies of the late 1920s had the predictable effect of encouraging localized and personal abuses in the war against social undesirables. Local soviets were aided in their work by a wave of denunciations,71 though it seems they scarcely needed this assistance, as in many cases they were already itching to take control of dachas occupied by “former people.” In 1927–28 a resident of Kuntsevo named Perevezentsev, who had lived with his wife in the same dacha for seventeen years, had had to suffer the forced occupation of several rooms by the secretary of the local soviet. The justification for this action was that he and his wife, having owned seven dachas in Kuntsevo before the Revolution, had retained one dacha each; the local soviet argued that they should move together into one. To add to the pressure, the secretary of the Party cell of the soviet and secretary of the local police committee moved in and began to terrorize the owners, storming into the house drunk at night and threatening them with a revolver. For this behavior the people’s court gave him a derisory fine of 10 rubles for “arbitrariness” (samoupravstvo); the dacha’s owners were evicted all the same.72

The 1920s thus culminated in an assault on exurban settlements whose aim was to eliminate the prerevolutionary dacha owner. Yet far from spelling the end of the dacha, the offensive prepared the way for its further development in the Stalin era.

Dachas in Stalin’s Time

In the 1920s leisure was not a well-established concept for Soviet society. Public discussion of the off-work behavior of Soviet citizens clustered around two opposing poles. On the one hand, mention was made of private activities such as drinking, dancing, and dacha rental; these were usually treated in an ambivalent, not to say hostile, manner. On the other hand, more approving accounts were given of collective and politicized recreational institutions such as rest homes (doma otdykha) and children’s colonies. Thus Serebrianyi Bor, formerly the “favorite residence for prominent Moscow merchants,” now became a leisure complex consisting of thirteen collective dachas, each accommodating between fifty and seventy people. One report explained: “There aren’t any sick people here. The people here just need a rest.” The daily timetable was strictly laid out: early rising was followed by calisthenics, swimming, walking, and sunbathing; drinking was strictly forbidden, and smoking was permitted only outside the buildings.73

All this changed in the early 1930s. Soviet society started to acquire a new ideology of leisure not just as a means of weaving citizens into a seamless collective or as a brief interlude between bouts of shock labor and social combat on the factory floor but rather as a cultural experience that could make an important contribution to the new Soviet way of life and the formation of a new Soviet citizen. It is around this time that the Soviet discourse on leisure—as something quite distinct from work—begins in earnest. As one slogan of the time ran: “Working in the new way means relaxing in the new way too.” In part, the new attitude toward leisure was reflected in practical measures. Existing facilities were to be expanded and improved.74 Parks, such as those surrounding the palaces in the Leningrad region, were to have extra facilities provided. In Detskoe (formerly Tsarskoe) Selo, accordingly, the number of visitors was expected to increase from 500,000 in 1933 to 945,000 in 1934.75 Quantitative improvements were matched by qualitative changes, as leisure institutions took account of the cultural advances proclaimed on behalf of Soviet society. New rest homes retained their function of collective, organized recreation, but the pattern of life they imposed was not so militarized as in the 1920s. As one article explained, things had moved on greatly from earlier vacation camps, where the only cultural work that went on was folk dancing, the only way of combating drunkenness was to destroy all alcoholic drinks on the premises, and the staff were dismayed by the uncivilized behavior of the “masses.”76

In a booklet of 1933 Soviet functionaries and their families were offered advice on how “correctly to organize their recreation, [how] most rationally to make use of their day off.” Such people were urged to take advantage of leisure and to take part in mass events in such prime greenbelt locations as Gorki, Arkhangel’skoe, Zvenigorod, and Kolomenskoe; in moments free from physical activities they might indulge in a bit of local history in a museum.77 In 1934, about 800 institutions were offering summer leisure activities in the Moscow region; the total number of beds was 90,000. Each summer weekend, approximately 500,000 Muscovites set off into the greenbelt.78 In 1936 Vecherniaia Moskva (the Moscow evening newspaper) proudly reported that from one station alone 250,000 Muscovites had headed out of town last weekend—and that most of these people were not permanent residents of satellite settlements or even dachniki but day trippers.79 The increased scope for leisure came to be seen as an important symptom of the general well-being of Soviet society; the history of dacha locations was mentioned only to contrast the vanity and frippery of the prerevolutionary leisured classes with the wholesomeness of Soviet recreational activities.80

The new approach to leisure had a parallel in public discussion of housing and settlement. Debates on architecture and town planning in the first half of the 1920s had been dominated by a generation that took seriously Marx’s promise of a communist lifestyle that would harmoniously integrate urban and rural environments. The three main models proposed (linear urban growth, the compact city [sotsgorod] and deurbanization) had something very important in common: they all presupposed the thoroughgoing resettlement of the Soviet population with the aim of eliminating urban agglomerations.81 The implications of these projects were as negative for the prerevolutionary dacha as they were for the major cities: the idea was to break down the dualism whereby economically productive life proceeded in overcrowded urban settlements and recreation in the greenbelt.

At the end of the 1920s, however, it was decided that the Soviet Union should not aspire to the harmonious, integrated life of the small town. As before, people would have to live in city centers or in densely populated industrial suburbs. The reasons for the abandonment of “utopian” planning projects were in large part economic: a spread of low-density settlement required too high and even a level of infrastructure, and it did not square with the absolute commitment to headlong industrialization.82 But the more traditional planning policies of the 1930s also reflected a new concern with everyday life and the individual. The conflict between the culture of the 1920s and that of the 1930s forms the subject of a 1931 story by Konstantin Paustovskii in which an avant-garde architect named Gofman leads a ski party to a part-built vacation camp that he has designed. The main building is cylindrical, its curved windows are made of unbreakable glass, the climate inside is artificially controlled so as to be summery all year round, and its walls are so thin that they let in the sounds of the natural world from outside. As Gofman combatively explains: “Cities have had their day. If you . . . think that this is incorrect, then Engels thought otherwise. Each state system has its own particular forms of human settlement. Socialism doesn’t need cities.” The accompanying journalist, however, finds the design cold and impersonal: “In every house . . . there should be a certain stock of useless objects. In every house there should be at least one mistake.” Gofman is duly summoned to a committee meeting, where he is accused of “unnecessary functionalism” and objections are made to the costliness of his design. At the end of the story he goes swimming and conveniently drowns before the Soviet architectural community has had time to show him the error of his ways (and before the author has had to face up to the moral implications of the conflict he has outlined).83

Paustovskii’s story accurately reflects the movement away from deurbanizing projects, a tendency that enabled the dacha to regain some of the positive connotations it had lost in the 1920s. The Soviet Union, it was commonly argued, must avoid the suburban sprawl so characteristic of England and America, and dachas could help to preserve the greenbelts around the major cities. They had the further virtue of lessening the pressure on rest homes and sanatoria, of which the provision was inadequate throughout the Soviet period and especially in the 1920s. And summer houses were in fact more important to the Russians than to the British and the Americans, given the long winters, the short building season, and the unsanitary conditions that prevailed in cities. “Dacha in the narrow sense of the word is a purely Russian phenomenon,” claimed the Great Soviet Encyclopedia in 1930.

Positive assessments of this kind could not, however, bring practical improvements on their own. The dacha’s increasing public respectability was not matched by the pace of exurban construction. The Moscow city administration, when it took stock of the available dacha resources in 1933, found little to gladden the hearts of the vacationing masses: the municipal dacha stock was badly depleted (the basic unit of dacha allocation in this period was the room, not the house), and other organizations had not done much to improve the situation.84 Leningrad faced very much the same problems. In July 1931, for example, the oblast ispolkom instructed various organizations to inspect properties (especially former palaces and estates) that might provide dacha space. The conclusion reached was quick and unequivocal: “The municipal dacha stock, after inspection on site, consists of isolated lodgings of the following types: mezzanines, small attic rooms, and small outbuildings. On transfer of the entire housing stock to the ZhAKTs [housing cooperatives], the latter have adapted accommodations formerly used as dachas to form winter housing.”85 Despite regular attempts to free up dacha space, it was clear that municipal provision, as in the 1920s, was not competing effectively with the private market.86

Given the inadequacy of the existing publicly administered dacha stock, the construction of new settlements became a matter of urgency. The Leningrad housing organization Zhilsoiuz was required to set up “dacha and allotment cooperatives” at the raion level and also under the auspices of particular factories. The production of prefabricated wooden dachas was to be stepped up; the housing department (Zhilotdel) was required to organize a competition for dacha design and to develop designs for cheap and simple furniture suitable for dachas. According to the stipulations of this competition, vacation accommodations were to come in three main types: the “single-apartment dacha” (odnokvartimaia dacha) intended for summer use only, with a plot of 600 square meters; the sblochennaia dacha (i.e., two semidetached dachas) designed for use all year round; and the pansionat for fifty people, which was also destined for year-round use.87 The plan was to put up no fewer than 5,000 standard dachas during 1932.88

The organization burdened with these considerable tasks was the Trust for Dacha and Suburban Housing Construction in Leningrad oblast (operational from August 1931). Over the three years of its existence, the trust was beset with the problems that afflicted all areas of production in the Stalin era: a poorly trained, inexperienced, and ill-disciplined workforce; a shortage of resources and of ready cash, given that debtors were slow to pay; constant struggles with other branches of production for access to equipment and raw materials; the pressure of relentless and unrealistic production targets (including the construction of many houses of the “winter type,” which were not the trust’s prime responsibility); and the cumbersome bureaucracy that any branch of the supply system entailed.

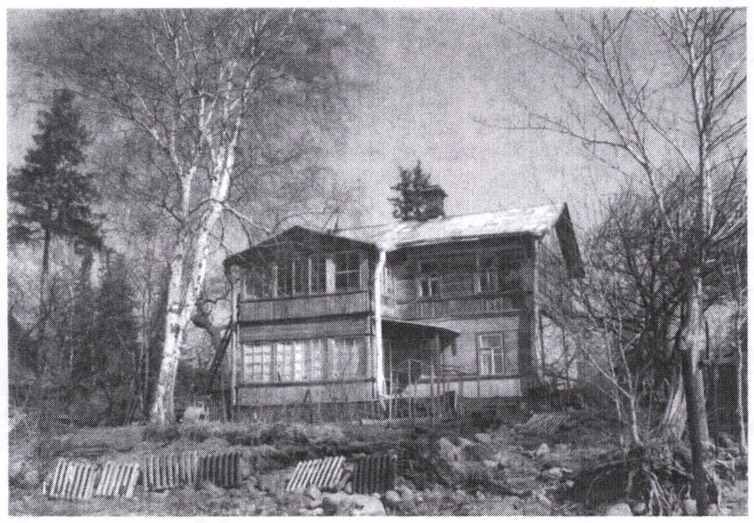

This dacha at Lisii Nos, which faces directly on the Gulf of Finland, would have been the ideal of many 1930s dachniki.

Despite these difficulties, the Leningrad dacha trust helped to create a new, centralized model of dacha rental and ownership for its region. It did not rent houses to private individuals but worked only with organizations: dachas were to be rented through trade unions, factories, and other state and Party institutions at standard rates. By 1934 such organizations were sending in a steady stream of applications requesting accommodations for their employees.89

The dachas built by the trust were of two main types: individual (for one family) and collective. The former typically consisted of two rooms and contained the following standard-issue furniture: two beds with mattresses (cost 210 rubles), six chairs (60 rubles), two tables (80 rubles), two buckets (5 rubles), one washstand (5 rubles). A list compiled in 1933 gave a total of 108 families resident in the trust’s flagship building developments at Mel’nichii Ruchei (just beyond Vsevolozhsk, on the railway line heading toward Lake Ladoga) and Lisii Nos (on the north side of the Gulf of Finland). The size of the houses they inhabited varied from one to six rooms, but the average was around two. Canteens were to provide meals for the regular dacha population, as well as for shorter-term visitors from the same kinds of organization. The tenants included employees of the following institutions: the dacha trust itself, the OGPU (the political police), banks, supply organizations, and various factories (including the Karl Marx, Sverdlov, and Stalin works).90

Many members of this middling stratum of the Soviet elite, however, were dismayed when they arrived at their dachas. The houses (especially their interiors) were often not completed, rubbish was still lying about the building sites, and amenities were very basic (and sometimes nonexistent). The canteens had not opened and there was little sign of a compensating supply of basic foodstuffs to the dacha settlements. In a report compiled at the end of 1932, the newly appointed head of the trust’s operational department was frank about the problems he faced: building standards were low, as was morale among the construction workers, given the abysmal conditions in which they worked; denied adequate temporary housing, workers had put up in semiconstructed dachas and left them in a wretched state.91 The press relentlessly kept such failings in the public eye.92

Newspapers also alleged that municipal dachas in the more desirable locations were allocated by personal acquaintance (by blat, in Soviet parlance). One journalist commented in 1933:

There are no rules for the distribution of dachas in the Moscow region. There are only memos [zapiski]. Memos come in three varieties: the friendly blat type, the string-pulling, and the naive, the last kind being written by organizations and enterprises that are appealing on behalf of their workers. The first kind is invariably successful, the second sometimes works, but the third—never.93

Although the trust was certainly a convenient target for accusations of corruption—one of the main Soviet techniques of governance, in the 1930s and after, was to attribute “popular” grievances to the failings of middle administration rather than to the Party elite or the system as a whole—there seems no reason to doubt that the administrative mechanisms of the time left ample scope for the practice of blat.94

In 1934 the trust was liquidated and replaced by local managing organizations 142 (dachnye khoziaistva) under the umbrella of Leningrad’s housing administration (Lenzhilupravlenie). A parallel development took place in Moscow with the transfer of dacha management to the regional communal department in April 1934.95 Control over the existing stock was further devolved by offering dachas for sale to factories and other organizations. But these administrative reshuffles did not change the general direction of policy: the trust had served as a means of transition from the chaotic situation of the 1920s to a more regulated system of distribution via state and Party organizations.

The prevailing trend was reinforced by developments in the cooperative movement. As we have seen, dacha cooperatives had existed since the 1920s, but in the 1930s their number and the strength of their institutional backing increased considerably.96 Cooperatives were recognized by the Moscow soviet as a way of mobilizing the resources both of individuals and of enterprises and of easing problems that the dacha trusts alone were clearly incapable of tackling. By November 1935, the managing organization Mosgordachsoiuz was able to report that the number of cooperatives had risen from 61 to 114 in little more than a year. But this was not necessarily grounds for self-congratulation: the funds available for dacha construction had not risen proportionately, and there were now 6,000 cooperative members on the waiting list for dachas; the total number of completed dachas was only 378.97 Individual settlements received grants (known as limity) out of the overall city budget, but this money went only a very small part of the way toward the costs of construction; the rest of the working capital was made up of members’ preliminary contributions, bank loans, and whatever funds were forthcoming from the cooperative’s sponsor organization (in many cases, the members’ employer).

The houses built and administered by the cooperatives were reserved for people occupying positions of responsibility and influence in particular organizations. Even for these people, however, dachas were not easy to come by. As the waiting list for dachas lengthened and resources remained scarce, many prospective dachniki could not contain their frustration and gave vent to grievances at general meetings of the cooperative or in personal petitions to Mosgordachsoiuz or some other branch of the city government. The most common allegation was that the rightful order of priority had been outweighed by personal considerations: that managers of the dacha stock had been swayed by blat, by the corrupt rendering of personal favors, instead of observing the cooperative statutes. It is impossible to judge how legitimate these protests were, especially as many are couched in the language of denunciation.98 What is clear, however, is that the prevailing economic conditions placed the managers of settlements in a position where they would have been hard pressed not to employ blat. To make use of contacts and to engage in practices that were not officially sanctioned was essential if construction work was to make any progress.

It is also clear that many members of dacha cooperatives served as unpaid “fixers” (tolkachi), or at least contributed a substantial amount of legwork, going from one institution to another to conduct the cooperative’s business. To be a cooperative aktivist did not primarily imply political duties: it meant having to negotiate deliveries of timber, standing in line to get the cooperative’s registration rubber-stamped, hiring casual laborers, and keeping an eye on them once they started work. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that many of these people, who had made a real practical contribution to the cooperative’s activities, felt they deserved preferential allocation of dacha space.99 Nor is.it surprising that their claims often met an outraged response from other cooperative members: Stalin-era fixers by definition were not open and accountable in their actions, and the criteria for determining priority in the allocation of dachas were often unclear.

The suspicions of ordinary members were fueled by the murky closed-doors deals that the cooperative boards of administration seemed to be making with the sponsor organization. They were dismayed by a general trend of dacha settlements to become more organizationally (or “departmentally”) based and less cooperative-like. That is to say, members tended to come from a single institution or a small number of linked institutions that retained close control over the construction and allocation of dachas. Settlements that had been established in the late 1920s were on the whole more heterogeneous. Mosgordachsoiuz complained in 1936 that at the Vneshtorgovets settlement, the sponsoring organization, the Ministry of Foreign Trade, was claiming a number of the dachas for its own people: “in such a situation the collective has no cooperative characteristics whatsoever and this construction is organizational under the cover of a cooperative.”100

Dachniki without such organizational backing, still the majority, continued, as they had done in the 1920s, to rent from house owners in villages and settlements accessible from Leningrad and Moscow. As a representative of the dacha trust noted in a report to the Leningrad soviet of April 1932 regarding the continuing shortage of dachas: “If Leningraders do in spite of all this manage to get out to a dacha during the summer, this is because they get living space by virtue of the self-compression [samouplotnenie] of the permanent population of the suburban district and thanks to the modest private housing stock.”101 A further source of dachas for rent, especially in the second half of the 1930s, was cooperative settlements: subletting a cooperative dacha was forbidden by Mosgordachsoiuz, and some people were expelled from their cooperative for such an offense, but in many settlements this practice seems to have been tolerated.102

A middling white-collar family would typically rent a house in a village where the local population would keep them supplied with basic produce; the time-consuming task of running the household through the summer months could further be alleviated by hiring a local girl as a servant (especially after the violent onset of collectivization, there was no shortage of peasant women willing to enter the domestic service of city folk).103 The dacha formed part of the way of life of overworked urban parents, who were able to send their children away for part of the summer. A Leningrad woman (born in 1929) recalled: “When I was a child we rented a dacha in Ozerki [very close to the city]. No kind of facilities, just a box of a room. And of course there was no space round about. . . . My mother was working almost without a break. . . . Meanwhile we spent the time at the dacha. . . . Our granny lived with us.”104 Similar were the experiences of Elena Bonner, who recalled spending one summer in the mid-1930s in a large house rented by her extended family in a village near Luga; as in the 1920s, the children and most of the women lived there all through the summer, while her politically active parents remained in the city.105 And Mikhail and Elena Bulgakov packed their family off to dachas to which they would make only occasional short trips during the summer; for the most part they made do with swimming in the Moscow River.106

This pattern of life—to remain in the city over the summer but make regular forays into the surrounding countryside—was by no means unusual in the 1930s, judging by the increase in summer rail traffic.107 On a typical day during the summer over 10 percent of Moscow’s population would head for the forests and lakes surrounding the city. And they had plenty of territory to choose from: the “suburban zone” was taken up predominantly by agriculture and forest (48 and 42 percent respectively) and only very slightly by towns and urban settlements (2.4 percent). That said, leisure facilities were still underdeveloped: the problem of keeping up with the increasing demand for leisure—without, however, violating the forest zone—was discussed regularly in the 1930s and after.108 Given the still inadequate leisure facilities in the Moscow area, it was argued that more land should be released for dacha construction in order to encourage workers to build. Settlements should not be allowed to grow too large (the proposed limit was 1,500 people), and dacha zones should be kept quite separate from other places of leisure. If construction was stepped up in this way, prices would be brought down.109 Yet if dacha building was allowed to continue unchecked, there was a serious danger that urban settlements would expand unacceptably, or that smaller dacha settlements would spring up in inappropriate places. Recent experience had shown that dacha plots were often too big (up to 2.5 hectares) to be ecologically sustainable.110

It seems that the greater part of the expansion of dacha settlements in the Moscow region in the 1930s can be put down to a process of creeping suburbanization: in 1936 it was estimated that 70 percent of the population of such settlements was made up by commuters (zagorodniki). As the Great Soviet Encyclopedia explained in 1930, dachas had “changed their function: they are not so much a summer dwelling for city people in need of a summer break as a dwelling for urban toilers, thus increasing the housing stock of the latter.”111 As for dachas proper (i.e., dachas as places for summer leisure), in 1934 there were places for 165,000 people (around 5 percent of the city’s population) in the Moscow region (compare this with 86,000 for rest homes, 35,000 for Pioneer camps, and 28,500 for preschool colonies). These 1930s dachniki were predominantly women (75 percent), presumably because draconian labor legislation kept men tied to the workplace (two weeks’ annual vacation was the norm in this period). Their class origin was likewise clearly marked: “There are no single dachniki. Very few workers. In the main, they are the families of employees [sluzhashchie].”112 In December 1934, Mosgordachsoiuz reported to Nikita Khrushchev, then Moscow Party boss, that of the 6,400 members of dacha cooperatives in the Moscow area only 455 (that is, 7 percent) were workers.113 But while the underrepresentation of proletarians was common knowledge, it rarely occasioned any public soul-searching.114 Rather, the Soviet press emphasized how urban “toilers” were benefiting from the new Soviet social welfare contract with the state: they were offered subsidized trips to rest homes, and the luckier ones might enjoy a full-blown vacation at a resort in the Crimea or the Caucasus.

The notion of a social divide between dacha residents and “mass” vacationers is supported by memoir accounts. One Muscovite’s recollections of childhood in the 1930s included walks past charming old dachas beyond the Sokol’niki gate that outwardly were unchanged since prerevolutionary times. “It seemed to us that these were some kind of ‘former people’ who were quietly living out their time behind tulle curtains.”115 The actress Galina Ivanovna Kozhakina recalled her 1930s experiences of dacha life in a similar light: “The dachas on neighboring plots were occupied by princes, former priests, and ruined nepmen. Our neighbor, once a noble lady, bred a huge flock of turkeys.”116 The presence of “former people” in dacha settlements was evidence not of privilege but of stigma. Nadezhda Mandelstam, for example, recounted how social undesirables such as her husband were commonly forbidden to live within a hundred-kilometer radius of Moscow. For this reason, they tended to cluster in village settlements just beyond that limit.117Closer to the city, conditions were often no better for less oppressed dacha residents: the more spacious dachas were turned into multiple-occupancy dwellings, the suburban equivalent of the communal apartment.

Such ad hoc arrangements were made possible by the still rather low penetration of outlying areas by the municipal authorities: private owners in former dacha settlements accounted for 59 percent of the total stock, while kolkhoz and peasant ownership was 28 percent. Cooperatives managed only 11 percent. Of the 274 population centers inhabited by dachniki in the Moscow region in the mid-1930s, 51 were “old” settlements, 55 were “new,” and the rest were ordinary villages. Prices for the season varied spectacularly, from 70 to 1,000 rubles.118

Once again advertisements can provide some information on the state of the dacha market. The back pages of newspapers in the 1930s were filled with notices concerning apartment swaps, lost dogs, household help, music lessons, and pieces of furniture, yet dachas were also featured. (As in the 1920s, we must assume that it was primarily a sellers’ market, and that most potential landlords had no need to go looking for tenants.) Dacha advertisements began to appear very early in the year—in the middle of the winter—and continued through to May and June, when they gave way to notices concerning the rental of rooms in city apartments (generally sublet by departed dachniki).119 Perhaps the most common type of dacha advertisement from February to May was that placed by institutions looking to rent or buy accommodations. Many organizations urgently needed to find living space for specialists arriving from other cities (hence the frequently encountered formula “Corners, rooms, dachas”). The demand for dachas was paralleled by the significant numbers of people who were trying to swap houses outside the city for central apartments, though it seems unlikely that these two types of demand were complementary: housing of all kinds—urban, suburban, and exurban—was in short supply.

The dacha shortage was exacerbated by the reluctance of many villagers to let out rooms because of concern that they would be liable for extra taxes. In Leningrad in 1932 it was noted that ordinary people could obtain dachas only through acquaintances, and even then at ridiculously high prices; the local authorities were often blamed for imposing extra charges that discouraged villagers from renting out their property and ultimately resulted in inflation.120 The ispolkom of Moscow oblast had already (in May 1932) taken the initiative in this matter by allowing collective farm workers and all other non-“kulak” landlords 300 rubles of untaxed nonagricultural income, by giving the dacha economy full exemption from the agricultural tax, and by forbidding local soviets to impose any unauthorized new charges on landlords and tenants. In the wake of the Great Leap Forward, village people needed much convincing that they would not be treated as kulaks if they rented out their property over the summer.121